Smiley

A smiley, sometimes called a smiley face, is a basic ideogram representing a smiling face.[1][2] Since the 1950s, it has become part of popular culture worldwide, used either as a standalone ideogram or as a form of communication, such as emoticons. The smiley began as two dots and a line representing eyes and a mouth. More elaborate designs in the 1950s emerged, with noses, eyebrows, and outlines. New York radio station WMCA used a yellow and black design for its "Good Guys" campaign in the early 1960s.[3][4][5] More yellow-and-black designs appeared in the 1960s and 1970s, including works by Harvey Ross Ball in 1963,[6][5][7] and Franklin Loufrani in 1971.[8][9][10] Today, The Smiley Company founded by Franklin Loufrani claims to hold the rights to the smiley face in over 100 countries. It has become one of the top 100 licensing companies globally.

There was a smile fad in 1971 in the United States.[11][12][4][13] The Associated Press (AP) ran a wirephoto showing Joy P. Young and Harvey Ball holding the design of the smiley and reported on September 11, 1971 that "two affiliated insurance companies" claimed credit for the symbol and Harvey Ball designed it; Bernard and Murray Spain claimed credit for introducing it to the market.[14] In October 1971[8] Loufrani trademarked his design in France while working as a journalist for the French newspaper France Soir.[8][15][16]

Today, the smiley face has evolved from an ideogram into a template for communication and use in written language. The internet smiley began with Scott Fahlman in the 1980s when he first theorized ASCII characters could be used to create faces and demonstrate emotion in text. Since then, Fahlman's designs have become digital pictograms known as emoticons.[17] They are loosely based on the ideograms designed in the 1960s and 1970s, continuing with the yellow and black design.

Word Origin and Etymology.

[edit]

The first use of the word ending "ey" is unknown. Aside from the use as an adjective, it is also a surname with origins in Scotland in the 17th century. It is said to be an evolution from the surname Smalley or Smellie.[18] The names "Smillie" and "Smiley" may have originated from a medieval nickname describing a person with a cheerful nature, stemming from the Middle English term "smile," which signifies "smile" or "grin."[19] The earliest known use of "smiley" in print as an adjective for "having a smile" or "smiling" was in 1848.[20][21] James Russell Lowell used the line "All kin' o' smily roun' the lips" in his poem The Courtin’.[22][23] According to the Merriam-Webster online dictionary the earliest known use of "smiley face" for "a line drawing of a smiling face" was in 1957.[1] In 1957 Jane McHenry wrote in a write-up in Family Weekly Magazine, Do-It-Yourself Carnival "Tape a paper plate to the mop head for a face, arranging string strands on each side for the hair. Draw a big smiley face on the plate!"[24] A year later, there was an illustration of a noseless smiling face containing two dots, eyebrows, and a single curved line for a mouth in a write-up in Family Weekly Magazine, Galloping Ghosts! by Bill Ross with the text:

"Collect six empty pop bottles and six cone-shaped paper cups. With crayons draw smiley faces on three of the cups and scary ones on the others. Put a cup on top of each bottle and line them up as 'ghosts.'...Keep score by counting five points for each scary-faced ghost knocked over and, since it is a night for spooks, only one point for each smiley!"[25]

Name of Designs

[edit]Early designs were often called "smiling face" or "happy face." In 1961 the WMCA's Good Guys, incorporated a black smiley onto a yellow sweatshirt,[26] and it was nicknamed the "happy face." The Spain brothers and Harvey Ross Ball both had designs in the 70s that concentrated more on slogans than the actual name of the smiley. When Ball's design was completed, it was not given an official name. It was however labeled as "The Smile Insurance Company" which appeared on the back of the badges he created. The label was due to the fact the badges were designed for commercial use for an insurance company. The Spain brothers used the slogan Have a nice day,[5][27] which is now frequently known for the slogan rather than the naming of the smiley.

The word smiley was used by Franklin Loufrani in France, when he registered his smiley design for trademark while working as a journalist for France Soir in 1971. The smiley accompanied positive news in the newspaper and eventually became the foundation for the licensing operation, The Smiley Company. [28]

Competing terms were used such as smiling face and happy face before consensus was reached on the term smiley.The name smiley became commonly used in the 1970s and 1980s as the yellow and black ideogram began to appear more in popular culture. The ideogram has since been used as a foundation to create emoticon emojis. These are digital interpretations of the smiley ideogram and have since become the most commonly used set of emojis since they adopted by Unicode in 2006 onwards. Smiley has since become a broader term that often includes both the ideogram design, but also emojis that use the same yellow and black design.

Ideogram history

[edit]Early history of smiling faces

[edit]Ingmar Bergman's 1948 film Port of Call includes a scene where the unhappy Berit (played by Nine-Christine Jönsson[29]) draws a sad face – closely resembling the modern "frowny" but including a dot for the nose – in lipstick on her mirror before being interrupted.[30][15] In September 1963, there was the premiere[31] of The Funny Company, an American children's TV programmer, had a noseless Smiling face used as a kids' club logo; the closing credits ended with the message, "Keep Smiling!"[32][33][34][35]

- Signature of Bernard Hennet, Abbot of Žďár nad Sázavou Cistercian cloister, in 1741, with smiley-like drawing

- Illustration from a book, printed in Regensburg in 1771

- Illustrations from the (1920) novel Drawing for Beginners by Dorothy Furniss

- A smiley face balloon from a Gregory FUNNY-B'LOONS ad page 20 of The Billboard March 18, 1922 page 20

- A promotional poster for the film Lili published in the New York Herald Tribune in 1953.

In the latter half of the 20th century, the face now known as a smiley has evolved into a well-known symbol recognizable for its yellow and black features. The first known combination of yellow and black was used for a smiling face was in late 1962, when New York City radio station WMCA released a yellow sweatshirt as part of a marketing campaign.[36][37] By 1963, over 11,000 sweatshirts had been given away. They had featured in Billboard magazine and numerous celebrities had also been pictured wearing them, including actress Patsy King and Mick Jagger.[3][15] The radio station used the happy face as part of a competition for listeners. When the station called listeners, any listener who answered their phone "WMCA Good Guys!" was rewarded with a "WMCA good guys" sweatshirt that incorporated the yellow and black happy face into its design.[38][39][40] The features of the WMCA smiley was a yellow face, with black dots as eyes and had a slightly crooked smile. The outline of the face was also not smooth to give it more of a hand drawn look.[40] Originally, the yellow and black sweatshirt (sometimes referred to as gold), had WMCA Good Guys written on the front with no smiley face.[16][36]

A number of United States–based designs of yellow and black happy faces emerged over the next decade.[41][7][16] State Mutual Life Assurance Company in Worcester, Massachusetts wanted to raise the morale of its staff following a merger with another insurance company.[42] Company Vice President John Adam, Jr. suggested a "friendship campaign." He put Joy Young, Assistant Director of Sales and Marketing, in charge of the project. According to Worcester Historical Museum's documents, Young requested that freelance artist Harvey Ball should design "a little smile to be used on buttons, desk cards and posters."[43] Ball completed the happy face in ten minutes and was paid $45 (equivalent to $462 in 2024).[39][5] His rendition, with a bright yellow background, dark oval eyes, full smile, and creases at the sides of the mouth,[40] was imprinted on more than fifty million buttons and became familiar worldwide. The design is so simple that it is certain that similar versions were produced before 1963, including those cited above. However, Ball's rendition, as described here, has become the most iconic version.[39][5] In 1967, Seattle graphic artist George Tanagi[44] drew his own version at the request of advertising agent, David Stern. Tanagi's design was used in a Seattle-based University Federal Savings & Loan advertising campaign.[45] Lee Adams's lyrics inspired the "Put on a Happy Face" ad campaign from the musical Bye Bye Birdie. Stern, the man behind this campaign, also incorporated the Happy Face in his run for Seattle mayor in 1993.[5] Throughout the 1960s the term happy face was used much more commonly in the United States than smiley describe earlier versions of commercial smiling face designs.[46]The Philadelphia-based brothers Bernard and Murray Spain also used the design on novelty items for their business, Traffic Stoppers. They focused on the slogan "Have a happy day,"[27][47] which mutated into "Have a nice day." As with Harvey Ball, they also produced happy face badges, producing over 50 million with New York button manufacturer NG Slater.[48][49][50]

In 1972, Frenchman Franklin Loufrani legally trademarked the use of a smiley face. He used it to highlight the good news parts of the newspaper France Soir. He simply called the design "Smiley" and launched The Smiley Company. In 1996 Loufrani's son Nicolas Loufrani took over the family business and built it into a multinational corporation. Nicolas Loufrani was outwardly skeptical of Harvey Ball's claim to creating the first smiley face. While noting that the design that his father came up with and Ball's design were nearly identical, Loufrani argued that the design is so simple that no one person can lay claim to having created it. As evidence for this, Loufrani's website points to early cave paintings found in France (dating from 2500 BC) that he claims are the first depictions of a smiley face. Loufrani also points to a 1960 radio ad campaign that reportedly made use of a similar design.[7][15]

The Smiley Company claims to own the rights to the Smiley trademark in one hundred countries.[51] Its subsidiary, SmileyWorld Ltd, in London, headed by Nicolas Loufrani, creates or approves all the Smiley products sold in countries where it holds the trademark.[28] The Smiley brand and logo have significant exposure through licensees in sectors such as clothing, home decoration, perfumery, plush, stationery, publishing, and through promotional campaigns.[52] The Smiley Company is one of the 100 top licensing companies in the world, with a turnover of US$167 million in 2012.[53] The first Smiley shop opened in London in the Boxpark shopping center in December 2011.[54] In 2022, there were many birthday celebrations for the smiley. Many of these came in the form of collaborations between The Smiley Company and large retailers, such as Nordstrom.[55]

The digital evolution of the Smiley began around the same time in the late 1990s, when the smiley first started to be incorporated into emoticon designs.[citation needed] Many people lay claims on when this began and who started it, but phone company Alcatel first included a digital smiley as a welcome screen in 1996.[citation needed] However, the first major development was the use of "toolbars" where users of various messaging applications (such as MSN messenger) could send emoticons or smileys for the first time on its messaging platform. The launch date is often hard to pinpoint, but it was likely on MSN Messenger 6 or 7 when it became an official toolbar, circa 2005.[56] Prior to this, unofficial toolbars had been used by millions of users to use digital smileys to convey or communicate emotion. One of the major toolbars was SmileyWorld's toolbar, a usable plugin developed by Nicolas Loufrani from his original Smiley Dictionary, with GIFs dating back even further on the site.[57] By 2003, the SmileyWorld toolbar had 887 original smiley icons.[citation needed] In the 1990s and 2000s, emoticons, smileys and later emojis were often interchangeable, but were used to describe pictograms used for digital communication.[58]

In recent times, the smiley has been used as a symbol for happiness or to spread joy in public places or at major events. The first recorded evidence of this was at the London 2012 opening ceremony, where The Smiley Company is also headquartered. Balls were released into the crowd as the show began to start. The balls were large but light enough that members of the crowd could use the balls like a beach ball, with each ball containing a large black smiley on one side.[59]

In China, there has been a steady growth in the use of smiley's in its culture both as a physical brand and also digitally.[60] This rise in popularity has led to a number of smiley merchandise stores opening in the country. By the end of 2024, 15 stores had opened in the country in cities such as Guangzhou, Suzhou and Xiamen. It was expected that the number could top 50 stores by the end of 2027.[61] Other countries in Asia were also experiencing a similar boom, including Thailand where 3 stores opened in 2024.[62]

Language and communication

[edit]The oldest known smiling face was found by a team of archaeologists led by Nicolò Marchetti of the University of Bologna. Marchetti and his team pieced together fragments of a Hittite pot from approximately 1700 BC found in Karkamış, Turkey. Once the pot had been pieced together, the team noticed that the item had a large smiling face engraved on it, becoming the first item with such a design to be found.[63] While this wasn't written in modern day form, cave drawings are considered a form of communication.

The earliest known smiling face to be included in a written document was drawn by a Slovak notary to indicate his satisfaction with the state of his town's municipal financial records in 1635.[64] The gold smiling face was drawn on the bottom of the legal document, appearing next to lawyer's Jan Ladislaides signature.[65] The Danish poet and author Johannes V. Jensen was famous for experimenting with the form of his writing, amongst other things. In a letter sent to publisher Ernst Bojesen in December 1900, he includes both a happy and sad face. It was in the 1900s that the design evolved from a basic eye and mouth design into a more recognizable design.[66]

A disputed early use of a smiling ASCII emoticon in a printed text may have been in Robert Herrick's poem To Fortune (1648),[67] which contains the line "Upon my ruins (smiling yet :)". Journalist Levi Stahl has suggested that this may have been an intentional "orthographic joke", while this occurrence is likely merely the colon placed inside parentheses rather than outside of them as is standard typographic practice today: "(smiling yet):". There are citations of similar punctuation in a non-humorous context, even within Herrick's own work.[68] It is likely that the parenthesis was added later by modern editors.[69]

On the Internet, the emojis has become a visual means of conveyance that uses images. The first known mention on the Internet was on 19 September 1982, when Scott Fahlman from Carnegie Mellon University wrote:

Yellow graphical smileys have been used for many different purposes, including use in early 1980s video games. Yahoo! Messenger (from 1998) used smiley symbols in the user list next to each user, and also as an icon for the application. In November 2001, and later, smiley emojis inside the actual chat text was adopted by several chat systems, including Yahoo Messenger.

The smiley is the printable version of characters 1 and 2 of (black-and-white versions of) codepage 437 (1981) of the first IBM PC and all subsequent PC compatible computers. For modern computers, all versions of Microsoft Windows after Windows 95[71] can use the smiley as part of Windows Glyph List 4, although some computer fonts miss some characters.[72]

The smiley face was included in Unicode's Miscellaneous Symbols from version 1.1 (1993).[73]

| Unicode smiley characters: | |||

| ☺ | U+263A | Alt+1 | White Smiling Face (This may appear as an emoji on some devices) |

| ☻ | U+263B | Alt+2 | Black Smiling Face |

| Miscellaneous Symbols also contains the frowning face: | |||

| ☹ | U+2639 | White Frowning Face | |

Later additions to Unicode included a large number of variants expressing a range of human emotions, in particular with the addition of the "Emoticons" and "Supplemental Symbols and Pictographs blocks in Unicode versions 6.0 (2010) and 8.0 (2015), respectively. These were introduced for compatibility with the ad-hoc implementation of emoticons by Japanese telephone carriers in unused ranges of the Shift JIS standard. This resulted in a de facto standard in the range with lead bytes 0xF5 to 0xF9.[74] KDDI has gone much further than this, and has introduced hundreds more in the space with lead bytes 0xF3 and 0xF4.[75]

Recent studies have investigated how various demographic factors influence individuals' interpretations and representations of smiley faces. A notable study by Clarke et al. (2018) involved an observational study with 723 participants were "asked to draw a smiley face for themselves" to examine the impact of gender and age on the way individuals depict smiley faces upon prompting. The findings revealed significant disparities: women and younger participants (aged 30 or below) were more inclined to illustrate traditional smiley faces, characterized by simple designs that include primarily eyes and a mouth, often excluding additional features such as noses or outlines. These results underscore the presence of demographic biases in the interpretation and depiction of smiley faces, emphasizing the need for careful consideration of these factors in research and surveys that utilize smileys or similar facial symbols, especially those that depend on self-reported outcomes or scales incorporating facial images to denote emotional or evaluative states.[76]

Symbolism in popular culture and applications

[edit]The smiley has now become synonymous with culture across the world. It is used for communication, imagery, branding, and topical purposes to display a range of emotions. In print, numerous brands used a yellow happy face to demonstrate happiness, beginning in the 1960s.

United States advertising campaigns

[edit]Before many countries had licensing and/or trademark restrictions on the smiley, different designs were used in advertising campaigns in the early to mid 1900s. Much of this activity was centered on the Northeastern United States.[citation needed] One of the first known commercial uses of a smiling face was in 1919, when the Buffalo Steam Roller Company in Buffalo, New York, applied stickers on receipts with the word "thanks" and a smiling face above it. The face contained a lot of detail, having eyebrows, nose, teeth, chin, and facial creases reminiscent of "man-in-the-Moon" style characteristics.[77] Another early commercial use of a smiling face was in 1922 when the Gregory Rubber Company of Akron, Ohio, ran an ad for "smiley face" balloons in The Billboard. This happy face had hair, a nose, teeth, pie eyes, and triangles over the eyes.[78] In 1953 and 1958, similar happy faces were used in promotional campaigns for the films Lili (1953) and Gigi (1958).[79]

Happy faces in northeastern United States, and later in the entire country, became a "common theme" within advertising circles from the 1960s onwards. This rose to prominence during the 1960s and was remixed and interpreted in different ways up until the 1980s. There were sporadic designs of smiling faces or happy face before this, but it wasn't until the WMCA in the early 1960s used yellow and black that the theme became more commonplace. Today trademark restrictions (e.g. The Smiley Company) make this kind of de-centralized design less likely or frequent.

In print

[edit]Franklin Loufrani used the word smiley when he designed a smiling face for the newspaper he was working for at the time. The Loufrani design came in 1971, when Loufrani designed a smiley face for the newspaper, France-Soir. The newspaper used Loufrani's smiley to highlight stories that they defined as "feel-good news."[28] This particular smiley went onto form The Smiley Company. Mad magazine notably used the smiley a year later in 1972 across their entire front page for the April edition of the magazine. This was one of the first instances that the smiling face had been adapted, with one of the twenty visible smileys pulling a face.[80]

In the United States, there were many instances of smiling faces in the 1900s. However, the first industry to mass adopt the smiley was in comics and cartoons.

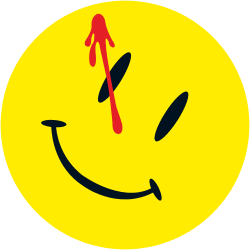

The logo for and cover of the omnibus edition of the Watchmen comic book series is a smiley badge, worn by the character the Comedian, with blood splattered on it from the murder which initiates the events of the story.

In the DC Comics, shady businessman "Boss Smiley" (a political boss with a smiley face for a head) makes several appearances.[81]

Music and film

[edit]As music genres began to create their own cultures from the 1970s onwards, many cultures began to incorporate a smiling face into their culture. In the late 1970s, the American band Dead Kennedys launched their first recording, "California über alles". The single cover was a collage aimed to look like that of a Nazi rally prior to World War II. It featured three of the vertical banners commonly used at such rallies, but with the usual swastikas replaced by large smileys.[82] In the UK, the happy face has been associated with psychedelic culture since Ubi Dwyer and the Windsor Free Festival in the 1970s and the electronic dance music culture, particularly with acid house, that emerged during the Second Summer of Love in the late 1980s. The association was cemented when the band Bomb the Bass used an extracted smiley from the comic book series Watchmen on the center of its "Beat Dis" hit single.

In addition to the movie adaptation of Watchmen, the film Suicide Squad has the character Deadshot staring into the window of a clothing store. Behind a line of mannequins is a yellow smiley face pin, which had been closely associated to another DC comic character, Comedian.[83] The 2001 film Evolution has a three-eyed smiley for its logo. It was later carried onto the movie's spin-off cartoon, Alienators: Evolution Continues.

In the film Forrest Gump it is implied the titular character inspired the smiley face design after wiping his face on a T-shirt while running coast to coast.

In the late-1980s, the smiley again became a prominent image within the music industry. It was adopted during the growth of acid house across Europe and the UK in the late 1980s. According to many, this began when DJ, Danny Rampling, used the smiley to celebrate Paul Oakenfold's birthday.[84] This sparked a movement where the smiley moved into various dance genres, becoming a symbol of 1980s dance music.[85]

In 2022, David Guetta collaborated with Felix Da Housecat and Kittin to release the song, Silver Screen, a reimagined version of the 2001 dance track. Guetta's version celebrated positivity and happiness.[86] The music video features a cameo from street artist, André Saraiva and portrays different groups portraying the message "Take The Time To Smile." The video partners that message with numerous smileys, on the side of buildings, on placards and on posters.

Physical products

[edit]Vittel announced in 2017 that they would be using the smiley on a special edition design of its water bottles. AdAge referred to its use as a "feel-good effect" and water bottles using the smiley icon had an 11.8% increase in sales, compared to the standard bottles, with 128 million bottles sold across Europe which featured the smiley-design.[87] In the UK, "Jammie Dodgers", a legendary biscuit line, incorporate the smiley engraved into circular cookies.

Art and fashion

[edit]As part of his early works, graffiti artist Banksy frequently used the smiley in his art. The first of his major works that included a smiley was his Flying Copper portrait, which was completed in 2004. It was during a period when Banksy experimented with working on canvas and paper portraits. He also used the smiley in 2005 to replace the face of the grim reaper. The image became known as "grin reaper."[88][89] In 2007, The Smiley Company partnered with Moschino for the campaign, "Smiley for Moschino."[90]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, fashion label Pull & Bear announced they would be releasing t-shirts with a smiley design incorporated on the front.[87] Other fashion labels that have used the smiley on their garments include H&M and Zara. The smiley has also featured on high-end fashion lines, including Fendi and Moncler.[91] High end French jeweller Valerie Messika produced white gold and yellow pendants, which contained a smiley face.[92]

For the 50th birthday of the Smiley, Galeries Lafayette in Paris, Beijing and Shanghai and 10 Nordstrom department stores sold limited edition smiley products to commemorate the anniversary.[93] During the same year, Lee Jeans announced the launch of a new clothing collection, Lee x Smiley.[94]

Gaming

[edit]In 1980, Namco released the now famous Pac-Man, a yellow faced cartoon character. In 2008, the video game Battlefield: Bad Company used the yellow smiley as part of its branding for the game. The smiley appeared throughout the game and also on the cover. The smiley normally appeared on the side of a grenade, which is something that became synonymous with the Battlefield series.[95]

The 1987 Atari ST game MIDI Maze, released on other platforms as Faceball 2000, features round, yellow Smileys as enemies. When a player is eliminated, these enemies taunt the player with the phrase "Have a nice day."

The Pokémon Ditto is based on the smiley face. Game Freak's staff described Ditto as "the weirdest Pokémon" in the franchise.[96]

Events, business, and social sciences

[edit]During the London 2012 opening ceremony, early on in the show a number of giant yellow beach balls were released into the audience. Each had a large smiley face.[97] Walmart uses a smiley face as its mascot.[98] User experience researchers showed that the usage of smileys to represent measurement scales may ease the challenges related to translation and implementation for brief cross-cultural surveys.[99]

The Brooklyn Bridge had a smiley projected onto the base one evening in 2020. The smiley was part of a wider campaign by The Smiley Company to increase happiness for New Yorkers. The 82 feet wide projected smiley featured light pink lipstick on the mouth of the smiley.[100]

In 2022, Assouline published "50 Years of Good News," a breakdown of the cultural development of the smiley and its use.[101]

In 2022, the International Day of Happiness was celebrated by projecting a smiley onto a number of landmarks around the globe. In Seoul, South Korea, a smiley celebrating happiness was projected onto The Seoul Tower.[102]

Ownership and alternative smileys

[edit]In 1997, Franklin Loufrani attempted to trademark rights to the ideogram he created in the United States. Walmart contested his application, as it began using its "Rolling Back Prices" campaign a year prior. The fallout led to a 2002 court case, and a seven-year ongoing case.[103] The fallout resulted in Wal-Mart phasing out the use of the smiley in 2006.[104][105] Despite that, Walmart sued an online parodist for alleged "trademark infringement" after he used the symbol. The District Court found in favor of the parodist when in March 2008, the judge concluded that Walmart's smiley face logo was not shown to be "inherently distinctive" and that it "has failed to establish that the smiley face has acquired secondary meaning or that it is otherwise a protectable trademark" under U.S. law.[106][107][108] In June 2010, Walmart and The Smiley Company founded by Loufrani settled their 10-year-old dispute in front of the Chicago federal court. The terms remain confidential.[109][110] In 2016, Walmart brought back the smiley face on its website, social media profiles, and in selected stores.[111]

The band Nirvana created its own smiley design in 1991.[112] It was claimed that Kurt Cobain was the designer of the Nirvana smiley. Following his death, this claim was one of the reasons why it became so iconic. As recently as 2020, media reports suggested a Los Angeles–based freelance designer was in fact behind the designs.[112]

Fashion house Marc Jacobs designed a smiley in 2018, which had a yellow outline, with the letters M and J replacing the eyes. The mouth design was similar to the original Nirvana design. In January 2019, legal representatives of Nirvana announced they were suing Marc Jacobs for a breach of copyright.[113] Following the announcement by a judge in Los Angeles that the suit could move forward,[114] Marc Jacobs announced a countersuit against Nirvana.[115] In 2020, a Los Angeles–based designer suggested that he was the creator of the Nirvana smiley and therefore became an interjector in the case between Nirvana and Marc Jacobs.[116]

See also

[edit]- Acid2

- Body language

- Emoji

- Emoticon

- Facial Action Coding System

- Galle (Martian crater)

- Henohenomoheji

- Kolobok

- Mr. Yuk

- Pac-Man (character)

- Pareidolia

- Red John

- SDSS J1038+4849

- Social intelligence

References

[edit]- ^ a b ""Smiley face." Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster". Archived from the original on 7 June 2024. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ Smiley-The Oxford dictionary of new words : a popular guide to words in the news(1991)

- ^ a b "New York "Good Guys" show". Billboard. 20 July 1963. Archived from the original on 7 June 2024. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ a b American fads by Richard A Johnson, 1985, p 121-124

- ^ a b c d e f Adams, Cecil (23 April 1993). "Who invented the smiley face?". The Straight Dope. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ^ "Ethridge, Mark. "Several Firms Claim to Be Originators of Smile Button." Nashua Telegraph. September 9, 1971". Archived from the original on 10 October 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ a b c Stamp, Jimmy (13 March 2013). Who really invented the Smiley face. Washington DC: Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ a b c "Wal-Mart fights to keep the smiley face:Retail giant says symbol personifies its price-reducing policy, but London-based firm says it secured rights years ago". CNN Money. 5 July 2006. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- ^ Les marques françaises : 150 ans de graphisme, 1824-1974 = French trademarks by Amiot, Edith(1990) p 236

- ^ INPI Brand: FR1199660 Archived 7 June 2024 at the Wayback Machine ***RENEWAL*** OF THE DEPOSIT MADE ON OCTOBER 1, 1971 AT THE INPI No. 120.846 AND REGISTERED UNDER No. 832.277

- ^ Fad Is Sweeping Charlotte - A Little Smile That's Going Places, The Charlotte News, Charlotte, North Carolina, Fri, Jul 9, 1971, Page 5. Archived 7 June 2024 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 31 Jan 2024

- ^ LATEST NATIONAL FAD Smiling Faces Now Appear On Everything From Ear Screws To Blue Jeans, Lubbock Avalanche-Journal, Lubbock, Texas, Fri, Sep 3, 1971, Page 80 (part 1) Archived 7 June 2024 at the Wayback Machine and (part 2) Archived 31 January 2024 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 31 Jan 2024

- ^ Put On A Happy Face, Time, August 30, 1971, Page 36

- ^ Nation in quest of symbol takes 'smile' pin to heart, Press-Telegram Long Beach, California, Sat, Sep 11, 1971, Page 10 Archived 31 January 2024 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 31 Jan 2024

- ^ a b c d History(of smiley by The Smiley company by way of The Wayback Machine)

- ^ a b c Coldwell, Will (25 September 2022). "Fifty years and $500m: the happy business of the smiley symbol". TheGuardian.com. Archived from the original on 7 June 2024. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ a b "Smiley Lore :-)". cmu.edu. Archived from the original on 19 July 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "Origin of the Smiley name". Smiley Family.

- ^ "Last name: Smiley". The Internet Surname Database. Name Origin Research. Retrieved 29 April 2025.

- ^ ""smiley" the online Merriam-Webster dictionary". www.merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com Retrieved 2022-01-09. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ Clarendon Press. (1989). smiley. The Oxford English Dictionary (Vol. XV, p. 790).

- ^ The Courtin’ By James Russell Lowell (1819–1891) Biglow Papers Archived 18 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2022-03-18

- ^ Do-It-Yourself Carnival by Jane McHenry Archived 19 February 2024 at the Wayback Machine Vicksburg Evening Post Vicksburg, Mississippi • Sun, Sep 8, 1957, Page 38--Part of the syndicated Junior TREASURE Chest Edited by Marjorie Barrows Editor of The Children' Hour

- ^ Galloping Ghosts! By Bill Ross Archived 4 March 2024 at the Wayback Machine The Tyler Courier-Times Tyler, Texas • Sun, Oct 26, 1958 Page 64--Part of the syndicated Junior TREASURE Chest Edited by Marjorie Barrows Editor of The Children' Hour

- ^ Everybody's Putting on a Happy Face, Asbury Park Press Asbury Park, New Jersey, Sun, Jul 25, 1971, Page 36 Archived 21 February 2024 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 02-21-2024

- ^ a b "Two Brothers Put The Smile On Buttons For Latest Fad" By Nancy B. Clarke, Women's News Service, The Daily Times-News Burlington, North Carolina, Sun, Aug 22, 1971, Page 20. Archived 31 January 2024 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 31 Jan 2024

- ^ a b c Golby, Joel (24 January 2018). "The Man Who Owns the Smiley Face". Vice. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ "Port of Call (IMDb)". IMDb. Archived from the original on 4 June 2024. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ Ingmarbergman.se. A still from the scene Archived 17 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Premiere to Be Held at Highland Theatre Archived 7 June 2024 at the Wayback Machine Highland Park News-Herald and Journal Los Angeles, California, Thu, Sep 5, 1963, Page 28

- ^ Savage, Jon (20 February 2009). "A design for life". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 November 2010. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ ""The Funny Company (1963)"". www.youtube.com. Archived from the original on 27 February 2024. Retrieved 27 February 2024.

- ^ The Funny Company, Inc. US Trademark Registration Certificate No. 764,727, Feb 11, 1964, Ser. No. 164,341, file Mar. 11, 1963 First Use Jan 10, 1963, First Use in Commerce Feb. 13, 1963 Archived 6 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine access date March 27, 2022

- ^ Woolery, George W. (1983). Children's Television: The First Thirty-Five Years, 1946-1981. Scarecrow Press. pp. 113–115. ISBN 0-8108-1557-5. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Focus on Deejay Scene". Billboard. 15 December 1962. p. 34. Archived from the original on 7 June 2024. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ I heart design : significant graphic design selected by designers, illustrators, and critics

- ^ Sooke, Alastair (3 February 2012), "Smiley's People (Radio 4): The million dollar smile", The Telegraph, archived from the original on 12 January 2022,

[Loufrani] points out that a smiley face was a key feature of a well-known promotional campaign for a radio network on America's East Coast in the late Fifties.

- ^ a b c Honan, William H. (14 April 2001). "H. R. Ball, 79, Ad Executive Credited With happy Face". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 June 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ a b c Doug Lennox, illustrated by Catriona Wight (2004), Now You Know More: The Book of Answers, vol. 2 (illustrated ed.), Dundurn, p. 50, ISBN 9781550025309, archived from the original on 7 June 2024, retrieved 21 November 2020

- ^ Button Helps Firms Gain 'Smile' Image, "Small Business World 1966-09:Vol 3 Iss 9 page 1.

- ^ A Grin That's Lasted 43 Years - Smiley Face Got Its Start In Worcester (part 1) Archived 20 February 2024 at the Wayback Machine and Smiley Grew With America’s Search For Positives(part 2) Archived 20 February 2024 at the Wayback Machine Hartford Courant, Hartford, Connecticut, Fri, Sep 29, 2006, Pages D01, D05

- ^ "The Smiley Face". Worcester Historical Museum.

- ^ "George Tanagi's Work Is All Around | The Seattle Times". archive.seattletimes.com. Archived from the original on 22 December 2024. Retrieved 22 December 2024.

- ^ "Smiley face pin from University Federal Savings, 1967 (Museum of History and Industry)". Archived from the original on 21 February 2024. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ "Don't put on a happy face! Are you using the smiley emoji all wrong?". The Guardian. 11 August 2021.

- ^ Catalog of Copyright Entries 3D Ser Vol 25 Pts 7-11A by Library of Congress. Copyright Office. 1971

- ^ Peter Shapiro, "Smiling Faces Sometimes", in The Wire, issue 203, January 2001, pp. 44–49.

- ^ "When You ☺ the Whole World ☺ With You, The New York Times(Oct. 16, 1971)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 February 2024. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ The smile button: It's Enough to Man Cry(part 1) By Joseph M Treen Newsday (Suffolk Edition), Melville, New York, Mon, Mar 20, 1972 page 3 A Archived 28 February 2024 at the Wayback Machine and (part 2 page 12 A)

- ^ Crampton, Thomas (5 July 2006). "Smiley Face Is Serious to Company". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ^ "Smiley Licensing | Company Profile by". Licensing.biz. Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ^ "Global License : Ranking the brands" (PDF). Rankingthebrands.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ Ivanauskas, Giedrius (16 January 2012). "Boxpark Shoreditch: Interview with Nicolas Loufrani CEO of Smiley | Made in Shoreditch - A Magazine About Style, Innovation, Dining, Nightlife and People in Shoreditch". Made in Shoreditch. Archived from the original on 7 March 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ^ Verdon, Joan (4 March 2022). "Nordstrom And Luxury Brands Help The Smiley Face Celebrate Its 50th Birthday". Forbes. Archived from the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "Microsoft set to release MSN Messenger 7.0 beta". NetworkWorld. 30 September 2004.

- ^ "Who Invented the Emojis". Smiley.com. Archived from the original on 15 June 2024. Retrieved 1 December 2024.

- ^ "Don't know the difference between emoji and emoticons? Let me explain". The Guardian. 6 February 2015. Archived from the original on 8 June 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2024.

- ^ Gunn, Frank (28 July 2012). "Spectators play with giant smiley face beach balls during the pre-show for the Olympic Games Opening ceremonies in London on Friday July 27, 2012". Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ Borak, Masha. "In China, the smiley face does not mean what you think it means". TechinAsia.

- ^ "The Smiley Company Expands to China". License Global.

- ^ Langsworthy, Billy (21 November 2024). "Smiley opens pop-up stores in Thailand". Brands Untapped.

- ^ Uzundere Kocalar, Zuhal (17 July 2017). "Ancient pot discovery in Turkey contests smiley origin". Anadolu Ajansı. Archived from the original on 21 July 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ Votruba, Martin. "17th-century Emoji". Slovak Studies Program. University of Pittsburgh. Archived from the original on 10 August 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ^ Ghosh, Shreesha (6 February 2017). "World's Oldest Emoji Discovered? Scientists In Slovakia Say They Found 'Smiley Face Emoji'". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ Johannes V. Jensen var først ude med smileyen

- ^ Madrigal, Alexis C. (14 April 2014). "The First Emoticon May Have Appeared in ... 1648". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ "Emoticon: Robert Herrick's 17th-century poem "To Fortune" does not contain a smiley face". Slate Magazine. 15 April 2014. Archived from the original on 20 July 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "smileys, emoticons, typewriter art". Text Patterns - The New Atlantis. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ^ Fahlman's original message Archived 13 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- ^ "WGL Assistant v1.1: The Multilingual Font Manager". Archived from the original on 24 March 2008.

- ^ Announcing WGL Assistant. Announcement: WGL Assistant V1.1 Beta available Archived 13 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, comp.fonts, 27 July 1999, Microsoft Typography – News archive.

- ^ wikibooks:Unicode/Character reference/2000-2FFF

- ^ "Original Emoji from DoCoMo". FileFormat.info. Archived from the original on 19 July 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ "Original Emoji from KDDI". FileFormat.info. Archived from the original on 19 July 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ Clarke, M., McAneney, H., Chan, F., & Maguire, L. (2018). Inconsistencies in the drawing and interpretation of smiley faces: an observational study. BMC Research Notes, 11, Article 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-3185-0

- ^ van Den Berg, Erik. "De smiley is niet stuk te krijgen". de Volkskrant. Archived from the original on 5 April 2024. Retrieved 5 April 2024.

- ^ ""The Gregory Rubber Co Toys ad on page 20 of The Billboard March 18, 1922"". commons.wikimedia.org. Archived from the original on 11 August 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ An early smiley in an ad for the movie LILI (1953). Archived 23 February 2024 at the Wayback Machine (newspapers.com) Daily News, New York, New York, Tue, Mar 10, 1953, Page 312

- ^ "Front cover of Mad". No. 150. Mad. April 1972. p. 1.

- ^ "The True Story of The Smiley Face T-shirt by Imri Merritt, August 15, 2022". Archived from the original on 20 February 2024. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ Johnson, Heather. "Dead Kennedys' 'California Uber Alles' Archived 2014-11-10 at the Wayback Machine". Mix Online. 1 October 2005.

- ^ Steinberg, Nick (10 August 2016). "20 Hidden Details In 'Suicide Squad' You May Have Missed". Goliath. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ "The strange, tangled history of the acid house smiley". Red Bull. 18 April 2018. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ "Acid History: How The Smiley Became The Iconic Face Of Rave". ElectronicBeats magazine. 5 January 2017. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ Crews, Isaac (12 March 2022). "David Guetta Joins Smiley's Campaign Of Positivity With An Exclusive Video Release For Upbeat Anthem 'Silver Screen'". Sounderground. Archived from the original on 7 June 2024. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ a b "How Smiley's "Defiant Optimism" Helps Brands emerge from Darker Times". AdAge. June 2021. Archived from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ "The Staying Power of the Smiley Face". Artsy. 15 August 2019. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ O'Brien, Jennifer. "Banksy to sell works at Art Source fair in Dublin". The Times. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ "The Smiley Company's Evolution From Licensor to a €350m Lifestyle Brand". Business of Fashion. 15 March 2022. Archived from the original on 7 June 2024. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ Gallagher, Jacob (28 May 2019). "The Shockingly Large Business Behind the Iconic Smiley Face". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ Baërd, Elodie (21 February 2022). "Joaillerie: Messika célèbre les 50 ans de Smiley avec le sourire" (in French). Le Figaro. Archived from the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ Verdon, Joan (4 March 2022). "Nordstrom And Luxury Brands Help The Smiley Face Celebrate Its 50th Birthday". Forbes. Archived from the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ Russell Jones, John (9 March 2022). "Lee Celebrates Smiley 50th Anniversary with new Collection". MR (magazine). Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "Hands-on: Battlefield - Bad Company". Wired. 28 February 2008. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ Eddy, Andy (February 2011). "Feature". @Gamer. No. 6. Best Buy.

Andy toured the Game Freak offices, including the themed conference rooms—one of which is like a jungle. In fact, Andy later interviewed Matsuda and Sugimori here. [...] they deemed Ditto the weirdest Pokémon—a simple blob that began as a tribute to the classic yellow smiley face.

- ^ Gunn, Frank (28 July 2012). "Spectators play with giant smiley face beach balls during the pre-show for the Olympic Games Opening ceremonies in London on Friday July 27, 2012". Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ "Why the (Smiley) Face? A Chat with Walmart's CMO". Corporate - US (The Wayback Machine). 1 June 2016. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ Sedley, Aaron; Yang, Yongwei (30 April 2020). Sha, Mandy (ed.). Scaling the Smileys: A Multicountry Investigation (Chapter 12) in The Essential Role of Language in Survey Research. RTI Press. doi:10.3768/rtipress.bk.0023.2004. ISBN 978-1-934831-24-3. Archived from the original on 11 December 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ "Giant smiley face projected onto Brooklyn Bridge to cheer up New Yorkers". NY Post. 28 July 2020. Archived from the original on 5 April 2024. Retrieved 5 April 2024.

- ^ Seamons, Helen (5 February 2022). "We love: Fashion fixes for the week ahead – in pictures". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 June 2024. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "'스마일리' 보며 행복해져볼까[언박싱]" (in Korean). The Korea Herald. 21 March 2021. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "Wal-Mart seeks smiley face rights". BBC News. 8 May 2006. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2006.

- ^ Kabel, Mark (22 October 2006). "Wal-Mart phasing out smiley face vests". Associated Press.

- ^ Williamson, Richard (30 October 2006). "The last days of Walmart's smiley face". Adweek. Archived from the original on 2 January 2008. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Smith v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc". Citizen Vox. 28 March 2008. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2011. The relevant text is in the Order granting summary judgment: Timothy C. Batten Sr., "ORDER" (21 March 2008)", section "B. Threshold Issue: Trademark Ownership", case "1:06-cv-00526-TCB", document 103, pages 15–19

- ^ Smith v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. - 537 FSupp2d 1302 - March 20, 2008 - https://h2o.law.harvard.edu/collages/14555 Archived 14 September 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Smith v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. - 537 FSupp2d 1302 - March 20, 2008 - https://www.dmlp.org/sites/citmedialaw.org/files/2008-03-20-Order%20Granting%20Summary%20Judgment.pdf Archived 5 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sony, Astellas, Intel, Apple, Wal-Mart, Warner: Intellectual Property Archived 7 June 2024 at the Wayback Machine Victoria Slind-Flor, 1 July 2011, Bloomberg. The case is Loufrani v. Wal-Mart Stores Inc., 1:09-cv- 03062, U.S. District Court, Northern District of Illinois (Chicago).

- ^ "(Docket Entried and select Court filing) Loufrani v. Wal-Mart Stores Inc., 1:09-cv-03062, (N.D. Ill.)--CourtListener". Archived from the original on 24 October 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- ^ Smith, Aaron (2 June 2016). "Walmart's Smiley is back after 10 years and a lawsuit". CNNMoney. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ a b Rosenbaum, Claudia (23 September 2020). "California Graphic Artist Claims He, Not Kurt Cobain, Created Nirvana's Smiley Face Logo". Billboard. Archived from the original on 22 June 2021. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ Snapes, Laura (3 January 2019). "Nirvana sue designer Marc Jacobs over alleged copyright breach". The Guardian.

- ^ "Judge Allows Nirvana's Lawsuit Against Marc Jacobs to Proceed". Rolling Stone. 14 November 2019. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ "Marc Jacobs countersues Nirvana in T-shirt copyright dispute". The Guardian. 28 November 2019.

- ^ "Artist files lawsuit after claiming he came up with Nirvana's 'smily face' logo". NME. 25 September 2020. Archived from the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch