Abbas II of Egypt

| Abbas Hilmi II | |

|---|---|

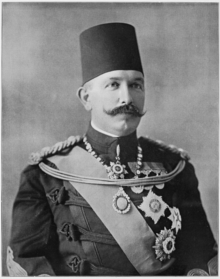

Abbas Hilmi II in 1909 | |

| Khedive of Egypt and Sudan | |

| Reign | 8 January 1892 – 19(20)(21) December 1914 |

| Predecessor | Tewfik I |

| Successor | Hussein Kamel (as Sultan of Egypt) |

| Born | 14 July 1874 Alexandria, Khedivate of Egypt[1] |

| Died | 19 December 1944 (aged 70) Geneva, Switzerland |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | Princess Emine Hilmi Princess Atiye Hilmi Princess Fethiye Hilmi Prince Muhammad Abdel Moneim Princess Lutfiya Shavkat Prince Muhammed Abdel Kader |

| House | Alawiyya |

| Father | Tewfik I of Egypt |

| Mother | Emina of Ilhamy |

Abbas Helmy II (also known as ʿAbbās Ḥilmī Pāshā, Arabic: عباس حلمي باشا; 14 July 1874 – 19 December 1944) was the last Khedive of Egypt and the Sudan, ruling from 8 January 1892 to 19 December 1914.[2][nb 1] In 1914, after the Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers in World War I, the nationalist Khedive was removed by the British, then ruling Egypt, in favour of his more pro-British uncle, Hussein Kamel, marking the de jure end of Egypt's four-century era as a province of the Ottoman Empire, which had begun in 1517.

Early life

[edit]Abbas II (full name: Abbas Hilmy), the great-great-grandson of Muhammad Ali, was born in Alexandria, Egypt on 14 July 1874.[4] In 1887 he was ceremonially circumcised together with his younger brother Mohammed Ali Tewfik. The festivities lasted for three weeks and were carried out with great pomp. As a boy he visited the United Kingdom, and he had a number of British tutors in Cairo including a governess who taught him English.[5] In a profile of Abbas II, the boys' annual, Chums, gave a lengthy account of his education.[6] His father established a small school near the Abdin Palace in Cairo where European, Arab and Ottoman masters taught Abbas and his brother Mohammed Ali Tewfik. An American officer in the Egyptian army took charge of his military training. He attended school at Lausanne, Switzerland;[7] then, at the age of twelve, he was sent to the Haxius School in Geneva,[citation needed] in preparation for his entry into the Theresianum in Vienna. In addition to Arabic and Ottoman Turkish, he had good conversational knowledge of English, French and German.[5][7]

Reign

[edit]Abbas II succeeded his father, Tewfik Pasha, as Khedive of Egypt and Sudan on 8 January 1892. He was still in college in Vienna when he assumed the throne of the Khedivate of Egypt upon the sudden death of his father. He was barely of age according to Egyptian law; normally eighteen in cases of succession to the throne.[5] For some time he did not willingly cooperate with the British, whose army had occupied Egypt in 1882.[3] As he was young and eager to exercise his new power, he resented the interference of the British Agent and Consul General in Cairo, Sir Evelyn Baring, later created the Earl of Cromer.[7] Lord Cromer initially supported Abbas but the new Khedive's nationalist agenda and association with anti-colonial Islamist movements put him in direct conflict with British colonial officers, and Cromer later interceded on behalf of Lord Kitchener (British commander in the Sudan) in an ongoing dispute with Abbas about Egyptian sovereignty and influence in that territory.[8]

At the outset of his reign, Khedive Abbas II surrounded himself with a coterie of European advisers who opposed the British occupation of Egypt and Sudan and encouraged the young khedive to challenge Cromer by replacing his ailing prime minister with an Egyptian nationalist.[3] At Cromer's behest, Lord Rosebery, the British Foreign Secretary, sent Abbas II a letter stating that the Khedive was obliged to consult the British consul on such issues as cabinet appointments. In January 1894 Abbas II made an inspection tour of Sudanese and Egyptian frontier troops stationed near the southern border, the Mahdists being at the time still in control of the Sudan. At Wadi Halfa the Khedive made public remarks disparaging the Egyptian army units commanded by British officers.[3] The British Sirdar of the Egyptian Army, the then Sir Herbert H. Kitchener, immediately threatened to resign. Kitchener further insisted on the dismissal of a nationalist under-secretary of war appointed by Abbas II and that an apology be made for the Khedive's criticism of the army and its officers.[9]

By 1899 he had come to accept British counsels.[10] Also in 1899, British diplomat Alfred Mitchell-Innes was appointed Under-Secretary of State for Finance in Egypt, and in 1900 Abbas II paid a second visit to Britain, during which he said he thought the British had done good work in Egypt, and declared himself ready to cooperate with the British officials administering Egypt and Sudan. He gave his formal approval for the establishment of a sound system of justice for Egyptian nationals, a significant reduction in taxation, increased affordable and sound education, the inauguration of the substantial irrigation works such as the Aswan Low Dam and the Assiut Barrage, and the reconquest of Sudan.[7] He displayed more interest in agriculture than in statecraft. His farm of cattle and horses at Qubbah, near Cairo, was a model for agricultural science in Egypt, and he created a similar establishment at Muntazah, just east of Alexandria. He married the Princess Ikbal Hanem and had several children. Muhammad Abdul Moneim, the heir-apparent, was born on 20 February 1899. [citation needed]

Although Abbas II no longer publicly opposed the British, he secretly created, supported and sustained the Egyptian nationalist movement, which came to be led by Mustafa Kamil Pasha. He also funded the anti-British newspaper Al-Mu'ayyad.[3] As Kamil's thrust was increasingly aimed at winning popular support for a nationalist political party, Khedive Abbas publicly distanced himself from the Nationalists and was labeled as being against Islam by said nationalists.[11] The western world would characterize him as a revolutionary against peace, although his main goal was to gain independence for Morocco. Their demand for a constitutional government in 1906 was rebuffed by Abbas II, and the following year he formed the National Party, led by Mustafa Kamil Pasha, to counter the Ummah Party of the Egyptian moderates.[3][12] However, in general, he had no real political power. When the Egyptian Army was sent to fight Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi in Sudan in 1896, he only found out about it because the Austro-Hungarian Archduke Francis Ferdinand was in Egypt and told him after being informed of it by a British Army officer.[13]

His relations with Cromer's successor, Sir Eldon Gorst, however, were excellent, and they co-operated in appointing the cabinets headed by Butrus Ghali in 1908 and Muhammad Sa'id in 1910 and in checking the power of the National Party. The appointment of Kitchener to succeed Gorst in 1912 displeased Abbas II, and relations between the Khedive and the British deteriorated. Kitchener, who exiled or imprisoned the leaders of the National Party,[3] often complained about "that wicked little Khedive" and wanted to depose him.

On 25 July 1914, at the onset of World War I, Abbas II was in Constantinople and was wounded in his hands and cheeks during a failed assassination attempt. On 5 November 1914 when Great Britain declared war on the Ottoman Empire, he was accused of deserting Egypt by not promptly returning home. The British also believed that he was plotting against their rule,[7] as he had attempted to appeal to Egyptians and Sudanese to support the Central Powers against the British. So when the Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers in World War I, the United Kingdom declared Egypt a Sultanate under British protection on 18 December 1914 and deposed Abbas II.[3][14]

During the war, Abbas II sought support from the Ottomans, including proposing to lead an attack on the Suez Canal. He was replaced by the British by his uncle Hussein Kamel from 1914 to 1917, with the title of Sultan of Egypt.[3][12] Hussein Kamel issued a series of restrictive orders to strip Abbas II of property in Egypt and Sudan and forbade contributions to him. These also barred Abbas from entering Egyptian territory and stripped him of the right to sue in Egyptian courts. This did not prevent his progeny, however, from exercising their rights. Abbas II finally accepted the new order on 12 May 1931 and formally abdicated. He retired to Switzerland, where he wrote The Anglo-Egyptian Settlement (1930).[10] He died at Geneva on 19 December 1944, aged 70,[7] 30 years to the day after the end of his reign as Khedive.[nb 1]

Marriages and issue

[edit]His first marriage in Cairo on 19 February 1895 was to Ikbal Hanim (Istanbul, Ottoman Empire, 22 October 1876 – Istanbul, 10 February 1941). They divorced in 1910 and had six children, two sons and four daughters:

- Princess Emina (Montaza Palace, Alexandria, 12 February 1895 – 1954),[15] unmarried and without issue,[16] received decoration of the Order of Charity, 1st class, 31 May 1895;[17]

- Princess Atiyatullah (Cairo, 9 June 1896 – 1971),[15] married twice and had issue, three sons,[16] received decoration of the Order of Charity, 1st class, 1 October 1904;[17]

- Princess Fathiya (27 November 1897 – 30 November 1923),[15] married without issue, received decoration of the Order of Charity, 1st class, 1 October 1904;[17]

- Prince Prince Muhammad Abdel Moneim, Heir Apparent and Regent of Egypt and Sudan, (20 February 1899 – 1 December 1979),[15] married and had issue, a son and a daughter;[16]

- Princess Lutfiya Shavkat (Cairo, 29 September 1900 – 1975),[15] married and had issue, two daughters,[16] received decoration of the Order of Charity, 1st class, 20 July 1907;[17]

- Prince Muhammad Abdul Kadir (4 February 1902 – Montreux, 21 April 1919);[15]

His second marriage in Çubuklu, Turkey on 28 February 1910 was to Hungarian noblewoman Javidan Hanim (born May Torok de Szendro, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S., 8 January 1874 – 5 August 1968). They divorced in 1913 without issue.[18]

Honours

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Sources give different dates for the deposition of Abbas. Some state that date as 20 or 21 December 1914.[3]

- ^ These three duchies were small independent free states that became part of the German Empire before World War I.

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Rockwood 2007, p. 2

- ^ Thorne 1984, p. 1

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hoiberg 2010, pp. 8–9

- ^ Schemmel 2014

- ^ a b c Chisholm 1911, p. 10

- ^ Pemberton 1897, Abbas II.

- ^ a b c d e f Vucinich 1997, p. 7

- ^ Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. p. 41.

- ^ Tauris, J.B. (17 July 1995). Kitchener Hero and Anti-Hero. pp. 62–63. ISBN 1-85532-516-0.

- ^ a b Lagassé 2000, p. 2

- ^ "The Pan-islamic Movement". The Times, London. 13 March 1902. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ a b Stearns 2001, p. 545

- ^ Morris 1968, p. 207

- ^ Magnusson & Goring 1990, p. 1

- ^ a b c d e f Soszynski, Henry. "Ikbal Hanim". Ancestry.com, Inc. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- ^ a b c d Tanman, M (2011). Nil kıyısından Boğaziçi'ne : Kavalalı Mehmed Ali Paşa Hanedanı'nın İstanbul'daki izleri = From the shores of the Nile to the Bosphorus : traces of Kavalalı Mehmed Ali Pasha Dynasty in İstanbul (in Turkish). İstanbul: İstanbul Araştırmaları Enstitüsu. pp. 375–376. ISBN 978-975-9123-95-6. OCLC 811064965.

- ^ a b c d Öztürk, D. (2020). "Remembering" Egypt's Ottoman Past: Ottoman Consciousness in Egypt, 1841-1914. Ohio State University. p. 74.

- ^ Van Lierop, Kathleen. "History- On this day- Abbas II of Egypt". All About Royal Families. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ "Kungl. Svenska Riddareordnarna", Sveriges statskalender (in Swedish), 1915, p. 725, retrieved 10 February 2021 – via runeberg.org

- ^ "Ritter-Orden: Kaiserlich-österreichischer Franz Joseph-orden", Hof- und Staatshandbuch der Österreichisch-Ungarischen Monarchie, 1913, p. 175, retrieved 9 February 2021

- ^ Shaw, Wm. A. (1906) The Knights of England, I, London, p. 342

- ^ Bille-Hansen, A. C.; Holck, Harald, eds. (1895) [1st pub.:1801]. Statshaandbog for Kongeriget Danmark for Aaret 1895 [State Manual of the Kingdom of Denmark for the Year 1895] (PDF). Kongelig Dansk Hof- og Statskalender (in Danish). Copenhagen: J.H. Schultz A.-S. Universitetsbogtrykkeri. pp. 15–16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 10 February 2021 – via da:DIS Danmark.

- ^ Shaw, p. 213

- ^ "Real y distinguida orden de Carlos III", Guía Oficial de España (in Spanish), 1930, p. 225, retrieved 10 February 2021

- ^ "Ritter-Orden: Österreichisch-kaiserlicher Leopold-orden", Hof- und Staatshandbuch der Österreichisch-Ungarischen Monarchie, 1913, p. 62, retrieved 9 February 2021

- ^ Shaw, p. 424

- ^ "Court Circular". The Times. No. 36799. London. 20 June 1902. p. 9.

- ^ "Ludeswig-orden", Großherzoglich Hessische Ordensliste (in German), Darmstadt: Staatsverlag, 1914, p. 14 – via hathitrust.org

- ^ "No. 27807". The London Gazette. 16 June 1905. p. 4251.

- ^ "Ritter-Orden: Königlich-ungarischer St. Stephan-orden", Hof- und Staatshandbuch der Österreichisch-Ungarischen Monarchie, 1913, p. 50, retrieved 9 February 2021

References

[edit]- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 9–10.

- Hoiberg, Dale H., ed. (2010). "Abbas II (Egypt)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. I: A-Ak - Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, IL: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- Lagassé, Paul, ed. (2000). "Abbas II". The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-7876-5015-3. LCCN 00-027927.

- Magnusson, Magnus; Goring, Rosemary, eds. (1990). "Abbas Hilmi". Cambridge Biographical Dictionary. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39518-6.

- Morris, James (1968). Pax Britannica: The Climax of an Empire. Harcourt Inc. p. 207. ISBN 9780156714662. LCCN 68024395.

- Pemberton, Max, ed. (February 1897). "none". Chums. Vol. 17, no. 232. Cassell and Company.

- Rockwood, Camilla, ed. (2007). "Abbas Hilmi Pasha". Chambers Biographical Dictionary (8th ed.). Edinburgh, UK: Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-0550-10200-3.

- Schemmel, B., ed. (2014). "Index Aa–Ag". Rulers. Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- Stearns, Peter N., ed. (2001). "The Middle East and North Africa, 1792–1914: e. Egypt". The Encyclopedia of World History: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Chronologically Arranged (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-395-65237-5. LCCN 2001024479.

- Thorne, John, ed. (1984). "Abbas II". Chambers Biographical Dictionary. Chambers, Inc. ISBN 0-550-18022-2.

- Vucinich, Wayne S. (1997). "Abbas II". In Johnston, Bernard (ed.). Collier's Encyclopedia. Vol. I: A to Ameland (1st ed.). New York, NY: P. F. Collier. LCCN 96084127.

Further reading

[edit]- Cromer, Evelyn Baring (1915). Abbas II. London: Macmillan and Co. OCLC 413286.

- Goldschmidt, Arthur (2000). Biographical Dictionary of Modern Egypt. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner. pp. 2–3. ISBN 1-5558-7229-8. LCCN 99033550.

- Pollock, John Charles (2001). Kitchener: Architect of Victory, Artisan of Peace. New York, NY: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 0-7867-0829-8. LCCN 2001035119.

- Sayyid-Marsot, Afaf Lutfi (1968). Egypt and Cromer: A Study in Anglo-Egyptian Relations. London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-1810-5. LCCN 75382933.

- Abbas II, Khedive of Egypt (1998). Sonbol, Amira (ed.). The Last Khedive of Egypt: Memoirs of Abbas Halmi II. Reading, UK: Ithaca Press. ISBN 0-8637-2208-3.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch