2,5-Diketopiperazine

The article's lead section may need to be rewritten. The reason given is: This article is not about the compound 2,5-diketopiperazine but the group of 2,5-diketopiperazines. (June 2024) |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name 2,5-Piperazinedione | |

| Preferred IUPAC name Piperazine-2,5-dione | |

| Other names Cyclic dipeptides, cyclo-dipeptides, DKPs, CDPs 2,5 dioxopiperazines (DOPs), dipeptide anhydrides | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) | |

| 3DMet | |

| 112112 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| EC Number |

|

| 217756 | |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID | |

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C4H6N2O2 | |

| Molar mass | 114.104 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 311–312 °C (592–594 °F; 584–585 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

2,5-Diketopiperazine is an organic compound with the formula (NHCH2C(O))2. The compound features a six-membered ring containing two amide groups at opposite positions in the ring. It was first compound containing a peptide bond to be characterized by X-ray crystallography in 1938.[1] It is the parent of a large class of 2,5-Diketopiperazines (2,5-DKPs) with the formula (NHCH2(R)C(O))2 (R = H, CH3, etc.). They are ubiquitous peptide in nature. They are often found in fermentation broths and yeast cultures as well as embedded in larger more complex architectures in a variety of natural products as well as several drugs.[2] In addition, they are often produced as degradation products of polypeptides, especially in processed foods and beverages.[3] They have also been identified in the contents of comets.[4]

Occurrence as natural products

[edit]There is a widespread occurrence of the 2,5-diketopiperazine core in biologically active natural products. The most structurally diverse 2,5-diketopiperazine natural products are based on tryptophan and proline modified by heterocyclisation and isoprenyl addition. These range from the hepatoxic brevianamide F (cyclo(L-Trp-L-Pro)) to the annulated tremorogenic verruculogen and the spiro-annulated spirotryprostatin B which represent a promising class of antimitotic arrest agents, to the structurally complex (+)-stephacidin A, a bridged 2,5-diketopiperazine that possess a unique bicyclo[2.2.2]diazaoctane core ring system and is active against the human colon HCT-116 cell line.[2]

- Biologically active Tryptophan-Proline 2,5-Diketopiperazine Natural Products

- (+)Stephacidin A

Other bridged 2,5-diketopiperazines include bicyclomycin, an antibacterial agent used as food additives to prevent diarrhea in animals while the thio derivatives such as the cytotoxic bridged epipolythiodioxopiperazine are represented by gliotoxin. The unsaturated derivatives are illustrated by phenylahistin the anti-cancer microtubule binding agent, and the mycotoxin roquefortine C found in blue cheeses.[2]

- Other Biologically active 2,5-Diketopiperazine Natural Products

Occurrence in foods and beverages

[edit]2,5-Diketopiperazines are often formed during chemical and thermal processing of food and beverages as the degradation products of polypeptides. They have been detected in stewed beef, beer, bread, Awamori spirits, cocoa, chicken essence, roasted coffee, Comte cheese, dried squid, aged saki and yeast extract. In food systems, 2,5-diketopiperazines have been shown to be important sensory compounds contributing to the taste of the final products and being perceived as astringent, salty, grainy, metallic or bitter. Although these range from proline, aromatic, aliphatic to polar 2,5-diketopiperazines, the proline 2,5-diketopiperazines are the most abundant and structurally diverse 2,5-diketopiperazines found in food. The valine derivative cyclo(L-Val-L-Pro) at a concentration of 1742 ppm, was identified as the most important bitter 2,5-diketopiperazine contributing to the bitter taste of roasted cocoa. It has also been found as one of the major 2,5-diketopiperazines in autolyzed yeast extract and stewed beef and is also present in chicken essence and coffee.[3] It has also been isolated from a variety of marine microorganisms and has been identified as an active LasI quorum-sensing signal molecule important for the plant growth promotion by Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[2] The most studied of all the simple 2,5-diketopiperazines is the histidyl-proline 2,5-diketopiperazine cyclo(L-His-L-Pro)[5] which is found in a variety of foods, with particularly high concentrations in fish and fish products. It is well absorbed orally, and crosses the blood–brain barrier via a non-saturable mechanism. It also occurs in humans[6] as a metabolite from the thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) and exhibits a wide variety of central nervous system, endocrine, electrophysiological, and cardiovascular effects.[5] Derivatives of cyclo(L-His-L-Pro) have been studied extensively to develop therapeutic agents for neurodegeneration.[7][2]

Structure and conformation

[edit]These cyclic dipeptides incorporate both donor and acceptor groups for hydrogen bonding. They are conformationally constrained nearly planar scaffolds. Diversity can be introduced at up to six positions and stereochemistry controlled at up to four positions. They are stable to proteolysis. These characteristics underpin theis biologically activity and utility in medicinal chemistry. As a consequence of their predominant biosynthetic origin from L-α-amino acids most naturally occurring 2,5-DKPs are cis configured as the cyclo(L-Xaa-L-Yaa) isomers. 2,5-DKPs epimerize under basic, acidic and thermal conditions. The composition of the cis and trans isomers in the equilibrium state varies widely depending on the bulk of the side chains, if a ring (e.g. proline) is present, or if the nitrogen atoms are alkylated . Although epimerization was historically an issue in the synthesis of 2,5-DKPs, several mild methods have been developed recently that avoid epimerization.[2]

Biosynthesis

[edit]2,5-DKPs are synthesized by a variety of organisms including humans. In general, they arise by the action of a tRNA-dependent cyclodipeptide synthases, a type of enzyme responsible for creating a cyclic amide linkage between two peptides.[8] The enzymes cyclodipeptide oxidase and S-adenosyl-methionine-dependent O/N methyltransferases act in tandem to chemically modify cyclic dipeptides.[8]

Synthesis

[edit]2,5-Diketopiperazines are typically prepared by one of three methods: amide bond formation, N-alkylation and C-acylation.

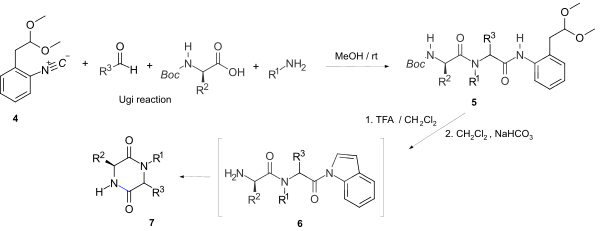

Amide bond formation

[edit]Most commonly 2,5-diketopiperazines are generated by cyclisation of dipeptides. In addition to the many methods of peptide synthesis, the Ugi reaction can be applied. Dipeptides with an ester terminus spontaneously cyclize often. Racemization can be problematic.[9] The Ugi reaction using an isonitrile, amino acid, aldehyde and amine, can produce a dipeptide in equally high yield and optical purity, to that formed by standard peptide couplings.[10] Commonly, an isonitrile is chosen to give a labile terminal amide to enable cyclization. For example, the direct 2,5-DKP ring formation via such an activated leaving group using the stable, easily accessible and versatile convertible isonitrile 1-isocyano-2-(2,2-dimethoxyethyl)-benzene 4 gave a one-pot synthesis of N-substituted 2,5-diketopiperazine's 7.[11]

The mild acidic and chemoselective post Ugi activation of 5 involving simultaneous indolamide formation and tert-butoxycarbonyl (Boc) removal gives the active amide 6 which allows cyclization to 7 without affecting other peptidic or even ester moieties and with stereochemical retention of the chiral centers.

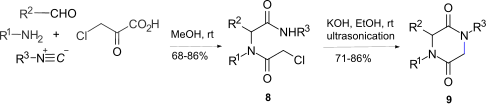

N-Alkylation

[edit]Intramolecular amide N-alkylation of alpha-haloacetamide amides 8 with ethanolic potassium hydroxide using ultrasonication gave the 2,5-diketopiperazines 9, where 8 was obtained by an Ugi reaction[12] between amines, aldehydes, isocyanides, and chloroacetic acid. However this route is limited by epimerization at the stereogenic centre and failure to obtain the 2,5-diketopiperazine ring if R1 = Alkyl.

C-Acylation

[edit]Formation of the 2,5-diketopiperazine ring by enolate acylation[13] was used in the construction of the 2,5-diketopiperazine ring in 11 by intramolecular cyclization of the enolate of 10 onto the carbonyl of the phenyl carbamate to give 11 in 90% yield.

Reactions

[edit]Reactivity at carbon (C-3 and C-6)

[edit]Regio- and stereocontrolled C-functionalization of 2,5-diketopiperazines at C-3 and C-6 involve enolate, radical and cationic precursors (and N-acyliminium ion) and are sensitive to polar and steric effects.

Alkylation of enolates

[edit]Alkylation of the bis-paramethoxybenzyl (pMB) protected 2,5-DKP 1 using the base LHMDS and an alkyl bromide R1Br, gave the mono-alkylated derivative 2, which on further alkylation gave the symmetrical trans-disubstituted derivative 3

Halogenation and displacement

[edit]The 3-monobromides 6 and the 3,6-dibromides 5 are prepared from the benzyl protected 2,5-DKP 4 by radical halogenation with N-bromosuccinimide in carbon tetrachloride. Displacement of these labile bromides readily occurs with a range of nucleophiles SR, OR, NR2, alkyl and aryl to give 7 .[2]

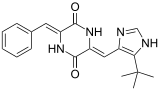

Aldol addition

[edit]A one- or two-fold aldol condensation of N-acetylated 2,5-DKP 8 gives access to 3-dehydro-2,5-diketopiperazines 9 and 3,6-didehydro-2,5-diketopiperazines 10 and the condensation of 8 can controlled in a stepwise fashion using triethylamine in dimethylformamide to give the unsymmetrical 3,6-didehydro-2,5-diketopiperazines 10 (R1 = Ar1, R2 = Ar2).[2]

Reactivity at nitrogen

[edit]Alkylation

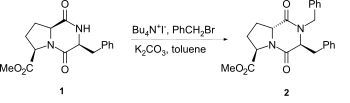

[edit]The most common method for alkylation of the lactam nitrogen of 2,5-diketopiperazines is based on the use of sodium hydride as base. However epimerisation can occur especially with proline-fused 2,5-diketopiperazines, even with milder methods such as under phase-transfer catalyst conditions for example 1 to 2.[2]

Reactivity at carbonyl carbons (C-2 and C-5)

[edit]Reduction

[edit]Reduction of the carbonyl groups of chiral 2,5-diketopiperazine with lithium aluminium hydride (LiAlH4) cleanly gives the corresponding chiral piperazines. For example, cyclo(L-Phe-L-Phe) 1 gives the chiral piperazine (2S,5S)-dibenzylpiperazine 2.[14]

Dihydropyrazine and pyrazine synthesis

[edit]Reaction of the lactam-derived enol phosphates 4 of 2,5-diketopiperazines with palladium catalyzed reactions (reduction, Suzuki and Stille cross-coupling reactions) enables the synthesis of a range of functionalised 1,4-dihydropyrazines 5 which can be aromatized to 1,4-pyrazines 6 in the presence of acid.[15]

Biological Functions

[edit]2,5-DKPs have been shown to play a role in interspecies bacterial quorum sensing. For example, the 2,5-DKP cyclo(Phe-Pro) has been shown to play a role in the regulation of gene expression in multiple different species of bacteria including V. fishceri, V. cholera, Lactobacillus reuteri, Staphylococcus aureus, among others.[8]

Applications

[edit]Therapeutics

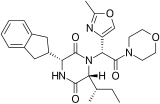

[edit]Numerous natural and synthetic 2,5-DKPs are bioactive. These small, conformationally rigid, chiral templates have multiple H-bond acceptor and donor functionality and have multiple sites for structural elaboration of diverse functional groups with defined stereochemistry. These characteristics not only enable them to bind with high affinity to a large variety of receptors, showing a broad range of biological activities, but also allow the development of the drug-like physicochemical properties required for the multiobjective optimization process of transforming a lead to a drug product. The structure–activity relationship (SAR) has been explored for many of these 2,5-DKP templates, and several have been developed into clinical drugs. These include tadalafil (a PDE5 inhibitor for erectile dysfunction), retosiban (an oxytocin antagonist for preterm labor), aplaviroc (a CCR5 antagonists for HIV), epelsiban (an oxytocin antagonist for premature ejaculation) and the experimental cancer drug plinabulin (NPI-2358/KPU-2) that is active in multidrug-resistant (MDR) tumor cell lines.[2]

- 2,5-Diketopiperazine Therapeutics

Due to their role in bacterial communication, 2,5-DKPs have a potential to be used as a medicine to treat bacterial diseases. For example, the 2,5-DKP cis-cyclo(Leu-Tyr) has been shown to inhibit bacterial biofilm formation; this property can be utilized to treat infections caused by the bacterial biofilm formation. These chemicals can be used to imitate quorum sensing signals to regulate gene expression of pathogenic bacteria and help fight against bacterial infection.[8]

Reagents

[edit]The diketopiperazine obtains from glycylserine is a reagent for the preparation of C-alkylated derivatives of glycine. This approach is useful for the production of unnatural amino acids with stereochemical control. The diketopiperazine skeleton protects both the N and O termini of the glycine. For this application, the diketopiperazine is O-alkylated with concomitant N-deprotonation to give what is called the Schöllkopf reagent.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ Corey RB (July 1938). "Crystal Structure of Diketopiperazine". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 60 (7): 1598–1604. doi:10.1021/ja01274a023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Borthwick AD (May 2012). "2,5-Diketopiperazines: Synthesis, Reactions, Medicinal Chemistry, and Bioactive Natural Products". Chemical Reviews. 112 (7): 3641–3716. doi:10.1021/cr200398y. PMID 22575049.

- ^ a b Borthwick AD, Da Costa NC (2017). "2,5-Diketopiperazines in Food and Beverages: Taste and Bioactivity". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 57 (4): 718–742. doi:10.1080/10408398.2014.911142. PMID 25629623. S2CID 1334464.

- ^ Shimoyama A, Ogasawara R (April 2002). "Dipeptides and diketopiperazines in the Yamato-791198 and Murchison carbonaceous chondrites". Origins of Life and Evolution of the Biosphere. 32 (2): 165–179. Bibcode:2002OLEB...32..165S. doi:10.1023/A:1016015319112. PMID 12185674. S2CID 21283306.

- ^ a b Minelli A, Bellezza I, Grottelli S, Galli F (Aug 2008). "Focus on cyclo (His-Pro): history and perspectives as antioxidant peptide". Amino Acids. 35 (2): 283–289. doi:10.1007/s00726-007-0629-6. PMID 18163175. S2CID 22563583.

- ^ Prasad C (Dec 1995). "Bioactive cyclic dipeptides". Peptides. 16 (1): 151–164. doi:10.1016/0196-9781(94)00017-Z. PMID 7716068. S2CID 44314137.

- ^ Cornacchia C, Cacciatore I, Baldassarre L, Mollica A, Feliciani F, Pinnen F (Jan 2012). "Diketopiperazines as neuroprotective agents". Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 12 (1): 2–12. doi:10.2174/138955712798868959. PMID 22070690.

- ^ a b c d Ilaria B (2014). "Cyclic dipeptides: from bugs to brain". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 20 (10): 551–8. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2014.08.003. PMID 25217340.

- ^ Tullberg M, Grøtli M, Luthman K (July 2006). "Efficient synthesis of 2, 5-diketopiperazines using microwave assisted heating". Tetrahedron. 62 (31): 7484–7491. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2006.05.010.

- ^ Dömling A (January 2006). "Recent developments in isocyanide based multicomponent reactions in applied chemistry". Chemical Reviews. 106 (1): 17–89. doi:10.1021/cr0505728. PMID 16402771.

- ^ Rhoden CR, Rivera DG, Kreye O, Bauer AK, Westermann B, Wessjohann LA (October 2009). "Rapid Access to N-substituted diketopiperazines by one-pot Ugi-4CR/deprotection+ activation/cyclization (UDAC)". Journal of Combinatorial Chemistry. 11 (6): 1078–1082. doi:10.1021/cc900106u. PMID 19795905.

- ^ Marcaccini S, Pepino R, Pozo MC (April 2001). "A facile synthesis of 2, 5-diketopiperazines based on isocyanide chemistry". Tetrahedron Letters. 42 (14): 2727–2728. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)00232-5.

- ^ Peng J, Clive DL (December 2008). "Asymmetric Synthesis of the ABC-Ring System of the Antitumor Antibiotic MPC1001". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 74 (2): 513–519. doi:10.1021/jo802344t. PMID 19067592.

- ^ Nagel U, Menzel H, Lednor PW, Beck W, Guyot A, Bartholin M (May 1981). "Versuche zur Rhodium (I)-katalysierten asymmetrischen Hydrierung von α-Acetamidozimtsäure mit monomeren und polymeren Aminophosphinen/Rhodium (I) Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of α-Acetamido Cinnamic Acid with Monomeric and Polymeric Aminophosphines". Zeitschrift für Naturforschung B. 36 (5): 578–584. doi:10.1515/znb-1981-0510. S2CID 95022362.

- ^ Chaignaud M, Gillaizeau I, Ouhamou N, Coudert G (August 2008). "New highlights in the synthesis and reactivity of 1, 4-dihydropyrazine derivatives". Tetrahedron. 64 (35): 8059–8066. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2008.06.080.

- ^ Wirth T (1997). "New Strategies toα-Alkylatedα-Amino Acids". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 36 (3): 225–227. doi:10.1002/anie.199702251.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch