2012 Nuevo Laredo massacres

| 2012 Nuevo Laredo massacres | |

|---|---|

| Part of Mexican Drug War | |

| Location | Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, Mexico |

| Coordinates | 27°29′10″N 99°30′25″W / 27.48611°N 99.50694°W |

| Date | 2012 |

Attack type | Turf war |

| Deaths | Unknown |

| Injured | Unknown |

The 2012 Nuevo Laredo massacres were a series of mass murder attacks between the allied Sinaloa Cartel and Gulf Cartel against Los Zetas in the border city of Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, across the U.S.-Mexico border from Laredo, Texas. The drug-violence in Nuevo Laredo began back in 2003, when the city was controlled by the Gulf Cartel. Most media reports that write about the Mexican Drug War, however, point to 2006 as the start of the drug war.[1] That year is a convenient historical marker because that's when Felipe Calderón took office and carried out an aggressive approach against the cartels. But authors like Ioan Grillo and Sylvia Longmire note that Mexico's drug war actually began at the end of Vicente Fox's administration in 2004,[1] when the first major battle took place in Nuevo Laredo between the Sinaloa Cartel and Los Zetas, who at that time worked as the armed wing of the Gulf Cartel.[1][2]

When Osiel Cárdenas Guillén, the former leader of the Gulf Cartel, was arrested in 2003, the Sinaloa Cartel, sensing weakness, tried to move in on Nuevo Laredo, unleashing a bloody battle.[3] Los Zetas, however, were successful in expelling the Sinaloa organization out of Nuevo Laredo, and have ruled the city "with fear" ever since.[3] Nevertheless, the Gulf cartel and Los Zetas broke relations in early 2010, worsening the violence across northeast Mexico.[4] The cartels are fighting for control of the corridor in Nuevo Laredo that leads into Interstate 35, one of the most lucrative routes for drug traffickers.[5] Nuevo Laredo is a lucrative drug corridor because of the large volume of trucks that pass through the area, and the multiple (exploitable) ports of entry.[6] Over 40% of all cargo crossings from Mexico to the United States crosses through the border checkpoints in Nuevo Laredo.[7] It is for the same reason that Tijuana and Ciudad Juárez are so valuable for the drug trafficking organizations.[6]

Past incidents in Nuevo Laredo

[edit]2003 shootout

[edit]At around 3 am on 1 August 2003, the Federal Investigations Agency (AFI) confronted a group of armed men in the streets of Nuevo Laredo. Members of the AFI were staying at a hotel when Juan Manuel Muñoz Morales, the attorney general of the city, called for help.[8] He was reportedly being chased by several individuals in a dark-colored truck. Consequently, the AFI officers followed the truck with seven of their vehicles, triggering a shootout between the police officers and alleged drug traffickers.[8] The armed confrontation lasted for more than 40 minutes, provoking "panic" and turning Nuevo Laredo into a "battlefield."[9] The gun detonations were heard throughout most of the city.[9] Some witnesses, who preferred to remain anonymous, claimed that they saw over "18 armed men in black with ski-masks."[9]

During the chase, five armed men in another vehicle shot at the police convoy. The triggermen in the two vehicles then engaged in a gunfight with the AFI for minutes, but one of the vehicles collided with a police truck. The vehicle the drug traffickers were in then caught on fire, and two of the gunmen were burned to death.[8] The third one died on the sidewalk. According to PGR, the three gunmen that were killed were members of Los Negros, a group of hitmen under the tutelage of Joaquín Guzmán Loera (a.k.a. El Chapo) and of the Juárez Cartel.[8] Rocket-launchers, along with an "inexact number of assault rifles," were reportedly used in the attack.[9] In addition, the government agency stated that 198 municipal police officers were to be investigated for possible connections with the Gulf Cartel; Manuel Muñoz, the attorney general who was being chased, was detained by the Mexican authorities. It is believed that he had liberated five members of Los Zetas who had been detained during the armed confrontation.[8] According to Esmas.com, this shooting was the first major gunfire in Nuevo Laredo between the Mexican authorities and cartel members in over thirty years.[10]

Between 1 January and 1 August 2003, 45 homicides were reported in Nuevo Laredo, along with 40 kidnappings.[9]

El Chapo enters Nuevo Laredo

[edit]

After the apprehension of Osiel Cárdenas Guillén in 2003, the former leader of the Gulf Cartel, his criminal organization went through a leadership crisis, since there was no visible leader to take the lead of the cartel.[11] Nonetheless, Joaquín Guzmán Loera, the drug boss of the Sinaloa cartel who is best known as El Chapo, "broke the rules" and penetrated into Tamaulipas. His organization began to kill police officers—forcing many to take a side with or against him—and assassinating rival cartel members. The Mexican Armed Forces and the program México Seguro were unable to put down the violence. For the first time in many years, the Mexican State was limited in its actions—and even surpassed—by the criminal organizations.[11] The Sinaloa Cartel stood to its firm intention to become the "hegemonic drug trafficking organization in Mexico."[12] And to do so, it had to control the cities along the U.S.-Mexico border. Back in the early 2000s, if a different drug trafficking organization wanted to traffic narcotics through a different corridor, they had to pay a fee to the cartel that controlled it. Hence, it often resulted in a high prize, since Osiel Cárdenas Guillén "knew how much every millimeter in his turf cost."[12]

No drug trafficking organization before the Sinaloa cartel had dared to take on the Gulf Cartel. But Juan José Esparragoza Moreno and El Chapo Guzmán were persuasive in moving on into Nuevo Laredo and the rest of Tamaulipas.[12] One of the first steps in the war between the Gulf and Sinaloa cartels began when Arturo Beltrán Leyva, alias El Barbas, hired Dionisio Román García (El Chacho), the leader of a gang who operated in Nuevo Laredo under the permission of Osiel in 2002. Nevertheless, El Chacho turned against the Osiel and the Gulf organization by deciding to work for the Sinaloa cartel and killing a Zeta member. This triggered a series of attacks and executions in Tamaulipas.[12] And, in order to put down the violence, El Barbas sought Arturo Guzmán Decena, one of the founders of Los Zetas, and told him that he "did not want any problems" with the Zetas, and that he would do his best to turn in El Chacho. Guzmán Decena accepted his apology, but told him that if anyone from the Sinaloa cartel wanted to traffic drugs inside the Gulf Cartel's territory, they had to be unarmed and under supervision.[12]

In May 2002, El Chacho was kidnapped in the city of Monterrey by members of Los Zetas, and eventually found dead in Tamaulipas, bearing signs of torture.[11][13] El Barbas then asked Osiel if Edgar Valdez Villarreal (La Barbie) could replace El Chacho, and he accepted. Los Zetas, however, were not convinced nor happy with Osiel's decision, because for them, "a betrayal is a betrayal."[12] Fifteen days after the capture of Osiel, Valdez Villarreal called Heriberto Lazcano Lazcano (who had taken the lead of Los Zetas after the death of Guzmán Decena in 2002) and said: "You have a week to leave the territories from Reynosa to Nuevo Laredo." With this, the war had started.[12]

2012 incursions

[edit]17 April 2012 massacre

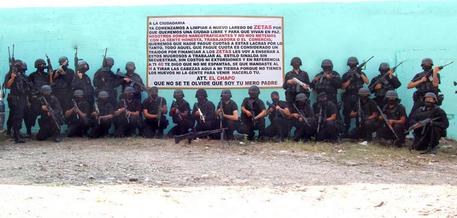

[edit]Dismembered remains of 14 men were found in several plastic bags inside a Chrysler Voyager in the border city of Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas on 17 April 2012.[14] All of those killed were between the ages of 30 and 35.[15] Mexican officials stated that they found a "messaged signed by a criminal group," but they did not release the content of the note,[16] nor if those killed were members of Los Zetas or of the Gulf Cartel.[17] CNNMéxico stated that the message left behind by the criminal group said that they were going to "clean up Nuevo Laredo" by killing Zeta members.[18] The Monitor newspaper, however, said that a source outside law enforcement but with direct knowledge of the attacks stated the 14 bodies belonged to members of Los Zetas who had been killed by the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, now a branch of the Sinaloa Cartel.[19] Following the attacks, the Sinaloa cartel's kingpin, Joaquín Guzmán Loera—better known as El Chapo Guzmán—sent a message to Los Zetas that they will fight for the control of the Nuevo Laredo plaza.[20] The message read the following:

"We have begun to clear Nuevo Laredo of Zetas because we want a free city and so you can live in peace. We are narcotics traffickers and we don't mess with honest working or business people. I'm going to teach these scums to work Sinaloa style—without kidnapping, without payoffs, without extortion. As for you, 40, I tell you that you don't scare me. I know you sent H to toss heads here in my turf, because you don't have the stones nor the people to do it yourself. Don't forget that I'm your true father."

— Joaquín Guzmán Loera, (El Chapo)[21]

Nuevo Laredo is considered a stronghold of Los Zetas,[22] although there were incursions by the Sinaloa Cartel in March 2012.[23][24] Consequently, Los Zetas responded two days later with incursions to Sinaloa, the home state of the Sinaloa Cartel.[25] The Sinaloa Cartel's first attempt to take over Nuevo Laredo happened in 2005, when Los Zetas was working as the armed wing of the Gulf Cartel.[26]

- InSight Crime analysis

The "40" in the message is a reference to Miguel Treviño Morales, a top leader of Los Zetas based in Nuevo Laredo, and longtime adversary of El Chapo Guzmán. The "H" is presumably Héctor Beltrán Leyva, the last remaining brother of the Beltrán Leyva Cartel.[27] The Beltrán Leyva organization, unlike the Zetas, has presence in Sinaloa state, and would probably have an easier time attacking the Sinaloa Cartel on its own turf. The message does not mention the fact that the Gulf Cartel is probably supporting the Sinaloa Cartel in carrying out the executions.[27] In addition, the banner suggests that the alliance between Los Zetas and the Beltrán Leyva Cartel remains intact as of 2012 despite its losses it lived in 2008. The message also suggests the differences in the modus operandi of Los Zetas and the Sinaloa Cartel, because as authors of InSight Crime allege, the Zetas have a reputation of operating through extortions, kidnappings, robberies, and other illicit activities; in contrast, the Sinaloa Cartel is known simply for drug trafficking. (Both assertions are not wholly true, but often reflect a popular sentiment). Guzmán attempted to take over Nuevo Laredo after the capture of the Gulf Cartel leader, Osiel Cárdenas Guillén, in 2003.[27]

Nevertheless, Guzmán retreated after a few years of bloody turf wars. The Sinaloa Cartel's return to Nuevo Laredo, however, was seen again in March 2012 after Guzmán reportedly left several corpses and a message heralding his return.[24] According to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, Nuevo Laredo is the busiest border crossing in terms of truck crossings with over 1.7 million trucks a year, more than double than any other crossing in the Mexico–United States border.[28] Nuevo Laredo is the fourth-busiest border crossing in terms of passenger vehicles.[28] Patrick Corcoran of InSight Crime believes that the turf war in Nuevo Laredo will bring a huge wave of violence, but also mentioned that the circumstances have changed since the split of the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas in early 2010. The current alliance between Guzmán's Sinaloa Cartel and the Gulf Cartel may successfully extract Los Zetas and give El Chapo the upper hand.

And once the Sinaloa Cartel gets established in Nuevo Laredo, it may possibly make moves to control Reynosa and Matamoros, Tamaulipas.[27]

- Investigations

On 24 April 2012, the attorney general of the state of Tamaulipas identified 10 of the 14 people killed. In addition, the Mexican authorities stated that those killed had "no relationship with the criminal group Los Zetas," and that they were in fact innocent civilians.[29] The U.S. Customs and Border Protection indicated that 7 out of the 14 who were killed were reportedly deported immigrants who were working illegally in the United States.[29] The authorities said that the massacre was carried out to generate "psychosis," because there is no concrete evidence of a "war between drug cartels" nor elements that indicate the presence of a group representing the Sinaloa Cartel in the border city of Nuevo Laredo.[30][31] Some of the bodies have been returned to their families.[32] The rest of the corpses have not been identified and remain in the Forensic Medical Services (SEMEFO).[31]

4 May 2012 massacre

[edit]23 bodies—14 of them decapitated and 9 of them hanged from a bridge—were discovered in Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, in an escalation of brutal violence involving rival drug gangs on the U.S. border.[33] In the first incident, at around 1:00 am on 4 May 2012, nine people were hanged from a bridge on the Mexican Federal Highway 85D with a message left behind by the killers.[34] Horrified motorists encountered the blood-stained bodies of four women and five men hanging off a bridge.[35][36] The banner left behind reportedly stated that those killed were the perpetrators of the car bomb in the city on 24 April 2012.[33] In addition, the 9 people who were hanged on the bridge were reportedly members of the Gulf Cartel who were killed by Los Zetas for "heating up" their turf.[37] The message read the following:

"Fucking (Gulf Cartel) whores, this is how I'm going to finish off every fucker you send to heat up the turf. You have to fuck up sometime and that's when I'm gonna put you in your place. We are going to fuck up El Gringo that keeps setting off car bombs; the fucker Juanito Carrizales and his friend El Tubi, who I killed because he kept crying like a bitch; El Metro 4 who asked Comandante Lazcano for mercy when he was kicking the shit out of him; and now El R1 in Reynosa and you. But it's okay, here are your guys. The rest went away but I'll get them. Sooner or later. See you around fuckers.[35]

In the second incident, which occurred hours later, 14 decapitated bodies were abandoned inside a vehicle in front of the Customs Agency;[38] the severed heads were left inside several ice coolers in front of the municipal palace.[38] The Mexican police said the second massacre could have been an act of revenge by the Gulf Cartel to Los Zetas for the earlier killings.[39][40] Along with the decapitated bodies was a message allegedly signed by Joaquín Guzmán Loera, where he demanded the municipality mayor of Nuevo Laredo, Benjamín Galván, along with other municipal and state leaders and public safety officials to recognize the Sinaloa cartel's presence in the area and stop insisting he is not in the city.[41] The message read the following:

"You want credibility that I am in NL? What will it take, bringing the heads of Zeta leaders? Or yours? Mr. [Benjamín Galván], since you want to give us a sweet treat, with you coming out saying that nothing is happening here and all is well, continue with the same and I assure you that heads will keep rolling. Keep making Z-40's case to say and deny that we already operate in Nuevo Laredo, just so that Lazcano will not scold this illiterate car washer. And you [Alfonso Olvera], Director of Public Security appointed entirely by Z-40, who is your buddy, keep declaring that my staff does not operate here in Nuevo Laredo. Or you, [Víctor Almanza], stating that the dismembered were masons, traders, migrants or simple and humble workers (and not what they were Zetas). Continue to deny my presence here in Nuevo Laredo and you will continue to see their heads. I do not kill innocent people to submit work as you are accustomed Z-40, all dead in Nuevo Laredo are pure scums, in other words, pure Z. Sincerely, your father."[42]

— Joaquín Guzmán Loera, (El Chapo)

Car bomb attacks

[edit]At around 8:00 a.m. on 24 April 2012 in Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, a car bomb exploded outside the city's police department.[43] When the Mexican military arrived at the area of the explosion, they engaged in a confrontation with cartel members who shot them upon their arrival.[44] There was one civilian who was injured as a result of the car bomb.[45] The Blog del Narco credited the attacks to Joaquín Guzmán Loera (a.k.a. El Chapo), who reportedly left another message for Los Zetas about the Sinaloa cartel's incursion in Nuevo Laredo.[46]

In the second incident, suspected members of a drug trafficking organization opened fire at a hotel that the Federal police was using as barracks on 23 May 2012, and then set off a car bomb in front of the police dormitories.[47][48] A Chevrolet pickup truck exploded at around 5:30 a.m. inside the parking lot of Hotel Santa Cecilia in southern Nuevo Laredo, injuring 2 civilians and 8 police officers.[49][50] The blast was strong enough to partially damage several rooms in the hotel and a couple of vehicles.[50][51] Three of the ten police officers were wounded with third degree burns in half of their bodies, while the rest were treated for non-life-threatening wounds.[50] Many residents living in Nuevo Laredo and across the international border in Laredo, Texas were reportedly awaken by the car explosion.[52] Some Laredo residents also began calling 9-1-1 early in the morning as the cartel battles in Nuevo Laredo reached their peak.[53] One resident even said that the explosions in Nuevo Laredo made his house shake across the border.[53] Soon after the attacks, the Mexican Army put up a military checkpoint in the avenue where the hotel is situated.[54] In addition, this attack was the first attack directed to Tamaulipas' new state police force, which took over the duties of the municipal police forces that were considered ineffective and corrupt.[55] The authorities in the Mexican state of Tamaulipas believe that Los Zetas, one of Mexico's most powerful criminal groups, carried out the attack. Los Zetas are known for carrying out a number of attacks, but this one was described as "one of the most elaborate."[48]

A third car bomb was abandoned on 29 June 2012 in front of the municipal palace at around 11:00 a.m., and exploded just below the office of Benjamín Galván Gómez, the mayor of Nuevo Laredo.[56] Explosives were planted inside a gray Ford Ranger pickup truck, damaging more than ten vehicles that were parked near the car bomb and destroying dozens of windows in its surroundings.[56][57][58] The detonation was heard on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border.[59] Laredo police said they received calls from several residents reporting an explosion, and dispatched officiers to the international bridges in the Texan city. A plume of smoke was seen from the U.S. side too.[57] In addition, seven people who were near the explosion were injured.[60] The Federal police and the Mexican Army cordoned the crime scene, as paramedics stabilized the bystanders and transported them to the nearest hospital.[61] The Mexican authorities believe this car bomb attack was a form of "expression" by the criminal syndicates who operate in Nuevo Laredo and want to make their presence known.[60] The state of Tamaulipas pledged to intensify the security measures in Nuevo Laredo.[62]

Attacks against the media

[edit]On 19 March 2004, journalist Roberto Javier Mora García was stabbed 26 times outside his home in Nuevo Laredo.[63] On 6 February 2006, two armed men broke into the offices of El Mañana and detonated a grenade.[64] They also shot the outside walls of the installation with AK-47s and AR-15s before fleeing the scene.[64] According to La Jornada, the armed men shot the installation more than 100 times, injuring Jaime Orozco Tey, a journalist.[65] On 30 July 2010, a group of armed men in a vehicle threw a grenade at the offices of Televisa in Nuevo Laredo, damaging two vehicles.[66] On 26 September 2011, María Elizabeth Macías Castro, an editor of la Primera Hora newspaper, was decapitated; a note was left behind by Los Zetas, claiming responsibility for the killing.[67] The message read the following: "For those who don't want to believe, this happened to [María Elizabeth Macías Castro] because of [her] actions, for believing in the army and the navy. Thank you for your attention, respectfully, Los Zetas.[68]

Attacks against bloggers and social media users

[edit]On 13 September 2011, a man and a woman in their early twenties were hanged from a pedestrian bridge in Nuevo Laredo.[69] Their fingers and ears were mutilated, and both bore signs of torture.[69] The signs left behind declared that the pair were killed for posting denouncements of the drug cartel activities on the Internet.[70] The message read: "This is going to happen to all of those posting funny things on the Internet," one sign said. "You better (expletive) pay attention. I'm about to get you."[69] The killing was carried out by Los Zetas.[69] On 9 November 2011, a blogger was tortured and decapitated for allegedly denouncing against the organized crime groups online.[71] The man killed reportedly used the username "Rascatripa" in the site known as Nuevo Laredo en Vivo, where civilians post on the activities of Los Zetas.[71] The killers left another message on top of the corpse stating the following: "Hello! I'm Rascatripas and this happened to me for failing to understand that I should not report things on social media websites. With this last report I bid farewell to Nuevo Laredo en Vivo."[72] This man was the fourth killed by the cartels for posting against them on the Internet in less than two months.[73] The brutal killings sent "shock waves" to the online community, and Twitter users from Nuevo Laredo, Reynosa, and the Rio Grande Valley, along with other border communities, issued a joint statement asking for protection in November 2011.[74] The bloggers asked the Mexican government to solve the murders and protect freedom of speech.[74] Even the "hacker group" known as Anonymous stepped in and gave recommendations to the community in Nuevo Laredo to "be careful" when denouncing Los Zetas.[75]

Cartels silence the media

[edit]In another incident, a group of armed men attacked the offices of El Mañana newspaper at around 23:00 hours on 11 May 2012.[76] The Mexican authorities stated that no one was injured in the 5-minute shootout, but the offices and some vehicles were damaged when bullets impacted from the outside.[77] When the employees of El Mañana heard the detonations, they threw themselves on the floor, while others suffered nervous breakdowns.[78] Some witnesses mentioned that they heard grenade explosions during the attack. In addition, a message was reportedly left behind by the perpetrators.[79]

The damage was minimal, but the message was understood. El Mañana took the attack as a warning from the Sinaloa Cartel that it wants coverage claiming that they are taking over Nuevo Laredo and beating Los Zetas, therefore making the Sinaloa cartel look "tough" and Los Zetas "look weak."[80] The problem is that if the journalists decide to favor the Sinaloa cartel or Los Zetas, they will find themselves threatened by one of the cartels. In other words, one cartel threatens if there isn't coverage (Sinaloa cartel) and the other cartel threatens if there is coverage (Los Zetas).[80] Following the attacks, El Mañana declared that it will no longer report on news relating to drug-violence.[81] They may in fact be the first newspaper to publicly step down and stop covering all crime incidents involving stories of mafia groups fighting for control.[80] The day that the editorial stepped down, 49 decapitated bodies were found along a highway near Monterrey, Mexico's third largest city, and just 120 miles south of Nuevo Laredo. Most newspapers covered this incident, but El Mañana did not.[80] Again, on 10 June 2012, El Mañana suffered another grenade attack but only material damages were reported.[82] In response to the attacks, the newspaper issued the following message to the public:

We ask for the public's comprehension and will refrain, for as long as needed, from publishing any information related to the violent disputes our city and other regions of the country are suffering ... The company's editorial and administrative board has been forced to make this regrettable decision by circumstances we are all familiar with, and by the lack of adequate conditions for freely exercising professional journalism ... We will only address the (violent crime) issue through the opinions of professional analysts who study the phenomenon in an intelligent and responsible way ... [We will not] serve the petty interests of any de-facto power or criminal group.[83][84]

Many Mexicans have been relying on social media chatrooms and sites like Facebook and Twitter as traditional media "self-censor in the face of cartel violence."[85] Moreover, due to the violent attacks the press has received in Nuevo Laredo, news media have practiced "self-censorship," where local journalist prefer to silence the press and refuse to report on important incidents for fears of reprisals by the cartels.[86] Events that would go on the front-page of any newspaper—mass murders with over six dead, shooting incidents wounding three soldiers—often go unreported in Nuevo Laredo.[86] The cartels want the cities they control to appear calm in order to prevent the government from sending federal troops.[86] Consequently, the press, tired of extortions and death threats, prefers to go silent because there is no guarantee for their safety.[86]

Attacks against casinos

[edit]On 21 May 2012, the Mexican authorities were alerted that a casino was on fire in Nuevo Laredo. At around six in the morning, an anonymous call alerted the police that smoke was coming from a building.[87] By 8:00 a.m. the fire had been put down, but a portion of the casino was consumed by the flames.[87] Nonetheless, only material damages were reported.[88] Inside the casino were several containers holding large amounts of gasoline, which helped the authorities conclude that the arson was intentional.[87] The 'Amazonas' casino, as it was known, opened in February 2010; however, it was closed in March 2012 for operating illegally.[87] According to the Blog del Narco, several people from Nuevo Laredo knew that the casino was owned by Los Zetas.[89] The article was also mentioned that the Zetas ordered the closure of another casino known as 'El Juega Juega' to benefit 'Amazonas.'[89]

Three days later on 24 May 2012, the 'Maranho' nightclub, considered among the most popular in Nuevo Laredo, was set on fire between 2:00 and 3:00 a.m.[90][91] And according to unofficial accounts, a group of gunmen were the perpetrators, while some accounts mention that they used grenades and bombs.[92] The nightclub was "completely destroyed," but no victims were reported.[93] Other grenade explosions were heard across the border in Laredo, Texas,[94] while the residents turned to #LaredoFollow hashtag on Twitter to report on the violence.[95] Unconfirmed reports from KGNS-TV state that several places in Nuevo Laredo, including educational institutions, are under bomb threats. However, the main targets in the bomb attacks have been entertainment businesses with supposed ties with the mafias that operate in the city.[96]

Images

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Ioan Grillo (2012). El Narco: The Bloody Rise of Mexican Drug Cartels. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 336. ISBN 978-1408824337.

- ^ Longmire, Sylvia (29 June 2011). "BOOK REVIEW: "El Narco: Inside Mexico's Criminal Insurgency," by Ioan Grillo". Mexico's drug war. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ a b "At least 23 people killed in Mexican border city". Associated Press. 5 May 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2012.[dead link]

- ^ "23 people killed, most decapitated, in Mexican city near US border". The Washington Post. 4 May 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.[dead link]

- ^ "23 killed in Nuevo Laredo". The Dallas Morning News. 4 May 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ a b Longmire, Sylvia (5 May 2012). "Nuevo Laredo heats up as Sinaloa-Zetas conflict leaves 23 dead". Mexico's drug war. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ "Fourteen bodies found in eastern Mexico: officials". Agence France-Presse. 12 June 2012. Archived from the original on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d e González, Iván (1 August 2003). "Todo sobre el enfrentamiento en Nuevo Laredo". Esmas.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 23 November 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Pruneda, Salvador (1 August 2003). "Balacera en Nuevo Laredo". Esmas.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 3 April 2010. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ López, Primitivo (1 August 2003). "Balacera entre narcos y agentes de la AFI". Esmas.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 23 November 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ a b c Ravelo, Ricardo (2011). El narco en México (in Spanish). Random House Mondadori. ISBN 978-6073105644.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hernández, Anabel (2012). Los señores del narco (in Spanish). Random House Mondadori. ISBN 978-6073108485.

- ^ "Identifican a ejecutados en Nuevo León". El Siglo de Torreón (in Spanish). 4 April 2003. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- ^ "Mexico authorities say bodies of 14 men dumped in Nuevo Laredo". Los Angeles Times. 17 April 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ "Localizan 14 cadáveres dentro de vehículo abandonado en Nuevo Laredo". Milenio (in Spanish). 17 April 2012. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ "14 mutilated bodies found in Mexican border city". El Paso Times. 17 April 2012. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ Mosso, Rubén (18 April 2012). "Nuevo Laredo: hallan 14 cuerpos mutilados". Milenio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ "14 cuerpos mutilados fueron hallados en Nuevo Laredo". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). 17 April 2012. Archived from the original on 21 April 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ "14 bodies found in minivan outside Nuevo Laredo City Hall, according to Tamps. gov't". The Monitor. 17 April 2012. Archived from the original on 27 April 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ "El Chapo demuestra su poder en Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas". Blog del Narco (in Spanish). 18 April 2012. Archived from the original on 20 April 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ Schiller, Dane (18 April 2012). "Drug lord 'El Chapo' declares war on Zetas". The Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ^ "Mexican authorities find 14 dead in Nuevo Laredo". Borderland Beat. 17 April 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ "El Chapo Guzmán comienza limpia de Los Zetas en Tamaulipas". Blog del Narco (in Spanish). 26 March 2012. Archived from the original on 18 April 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ a b Corcoran, Patrick (28 March 2012). "'Narcomantas' Herald Chapo's Incursion into Mexico Border State". InSight Crime. Archived from the original on 9 April 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ Martinez, Chivis (28 March 2012). "Z40 Answers Chapo by Leaving His Own Butchery and Message". Borderland Beat. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ^ Schiller, Dane (18 April 2012). "Is 'El Chapo' back in border city of Nuevo Laredo?". The Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d Corcoran, Patrick (23 April 2012). "Bodies, Banner Herald Sinaloa Cartel's Push East". InSight Crime. Retrieved 24 April 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Border Crossing/Entry Data: Quick Search by Rankings". Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Archived from the original on 2 July 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ a b "Desligan al 'Chapo Guzman' de la masacre en Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas". La Policiaca (in Spanish). 24 April 2012. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^ "Desligan a Chapo de masacre de N. Laredo". Terra Networks (in Spanish). 24 April 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^ a b "Identifican a 7 de los 14 asesinados en Nuevo Laredo". Noticias de Tamaulipas (in Spanish). 24 April 2012. Archived from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ Guzmán, Julio Manuel (24 April 2012). "Identifican a 7 de 14 asesinados en Nuevo Laredo". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 27 April 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^ a b "Nuevo Laredo vive un viernes negro, jornada violenta deja 23 muertos". Excélsior (in Spanish). 4 May 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ "Los cuerpos de 23 personas son encontrados en Nuevo Laredo". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). 4 May 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ a b "Ejecutan y cuelgan a nueve personas en Nuevo Laredo". Blog del Narco (in Spanish). 4 May 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ "23 dead in day of horror for Mexico border city". Yahoo! News. 4 May 2012. Archived from the original on 16 May 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ "Suman 23 muertos en Nuevo Laredo, entre colgados y decapitados". Univision (in Spanish). 4 May 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ a b "Van 23 muertos en Nuevo Laredo, en ola de violencia". El Universal (in Spanish). 4 May 2012. Archived from the original on 7 May 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ "Bodies of 23 found dumped near U.S. border in Mexico drug war". Yahoo! News. 4 May 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ "Se recrudece violencia en Nuevo Laredo: 23 muertos". El Universal (in Spanish). 5 May 2012. Archived from the original on 7 May 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ^ "Pide 'El Chapo Guzman' al alcalde de Nuevo Laredo que deje de negar su presencia". La Policiaca (in Spanish). 6 May 2012. Archived from the original on 8 May 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ "Chapo Leaves Message with Decapitated Bodies Issues Threat against NL Mayor". Borderland Beat. 6 May 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ "Car bomb explosion followed by shootout in Nuevo Laredo". KGBT-TV. 24 April 2012. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ "Coche bomba y enfrentamiento en Nuevo Laredo". El Universal (in Spanish). 24 April 2012. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ "Confirman coche-bomba en Nuevo Laredo". Terra Networks (in Spanish). 24 April 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ "Reafirma El Chapo presencia en Tamaulipas con coche bomba". Blog del Narco (in Spanish). 24 April 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ "Photos of damage from hotel car bombing in Nuevo Laredo". KGBT-TV. 24 May 2012. Archived from the original on 29 May 2012. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ^ a b "Mexico gang launches car bomb near US border". Associated Press. 25 May 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.[dead link]

- ^ "Estalla coche bomba en Nuevo Laredo; 8 policías y 2 civiles resultaron heridos". La Jornada (in Spanish). 25 May 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ a b c Valencia, Nick (25 May 2012). "Gun and bomb attack on hotel in Mexican border town wounds 10". CNN International. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ "Estalla coche bomba en Nuevo Laredo; al menos 10 heridos". Excélsior (in Spanish). 24 May 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ "Bomb in Mexico felt in Texas". San Antonio Express-News. 24 May 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ a b "Laredo Residents Wake Up To Sounds of Explosions, Gunfire". KGNS-TV. 24 May 2012. Archived from the original on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ "Coche bomba explota en hotel en Nuevo Laredo". El Economista (in Spanish). 24 May 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ Weissenstein, Michael (24 May 2012). "Mexico Gang Launches Car Bomb Near US Border". ABC News. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ a b "Estallan auto frente a Palacio en Nuevo Laredo". El Universal (in Spanish). 29 June 2012. Archived from the original on 1 July 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ^ a b Buch, Jason (29 June 2012). "Car bomb rocks Nuevo Laredo". San Antonio Express-News. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ^ González, Héctor (29 June 2012). "Coche bomba estalla frente a alcaldía de Nuevo Laredo". Excélsior. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ^ "Possible Car Bomb at Nuevo Laredo City Hall". KGNS-TV. 29 June 2012. Archived from the original on 31 January 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ^ a b "Siete lesionados por granadazo: Gobierno de Tamaulipas". Milenio (in Spanish). 29 June 2012. Archived from the original on 1 July 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ^ "Car bomb wounds 7 in Mexican border city". Fox News Channel. 29 June 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ^ "Un coche bomba explota frente al edificio municipal de Nuevo Laredo". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). 29 June 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ^ "El asesinato de Roberto Mora García, director editorial de "El Mañana", lleva cinco años impune" (in Spanish). International Freedom of Expression Exchange. 24 March 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ a b "Diario "El Mañana" de Nuevo Laredo sufre atentado". Terra Networks (in Spanish). 12 May 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ "Irrupción armada en el periódico El Mañana de Nuevo Laredo; un herido". La Jornada (in Spanish). 6 February 2006. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ "Atacan El Mañana de Nuevo Laredo". El Mañana (in Spanish). 12 May 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ Chapa, Sergio (29 September 2011). "Journalist group condemns Nuevo Laredo editor's murder". KGBT-TV. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ "Another social media killing in Nuevo Laredo". San Antonio Express-News. 27 September 2011. Archived from the original on 20 November 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d Castillo, Mariano (14 September 2011). "Bodies hanging from bridge in Mexico are warning to social media users". CNN. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ "Balconear a criminales en Internet firmó su sentencia de muerte". Excélsior (in Spanish). 14 September 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ a b "Decapitan a cibernauta; van cuatro en dos meses". Proceso (in Spanish). 9 November 2011. Archived from the original on 15 November 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ "Nuevo Laredo: Man tortured and decapitated for allegedly denouncing cartel activity online". Borderland Beat. 9 November 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ Fitch, Nubia (9 November 2011). "Asesinan a otro usuario de redes sociales". Sexenio (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ a b Sergio, Chapa (10 November 2011). "Twitter users want justice after fourth social media murder in Nuevo Laredo". KGBT-TV. Archived from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ Althaus, Dudley (11 November 2011). "Gang sends message with blogger beheading". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ "Ataca comando a periódico en Nuevo Laredo". El Universal (in Spanish). 12 May 2012. Archived from the original on 15 May 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ "Armed men open fire on Mexican newspaper office in border city of Nuevo Laredo". The Washington Post. 12 May 2012. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ "Comando ataca a balazos el periódico El Mañana de Nuevo Laredo". Proceso (in Spanish). 12 May 2012. Archived from the original on 15 May 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ "Ataca comando periódico 'El Mañana' de Nuevo Laredo; no hay heridos". La Jornada (in Spanish). 12 May 2012. Archived from the original on 14 May 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d O'Conner, Mike (23 May 2012). "El Mañana cedes battle to report on Mexican violence". Committee to Protect Journalists. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ Turati, Marcela (14 May 2012). "Tras atentado, El Mañana dejará de publicar notas sobre narcoviolencia". Proceso (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 19 May 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ^ "Three Mexican news outlets targeted in one day". Committee to Protect Journalists. 11 July 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ Ioan Grillo (11 July 2012). "Mexico paper stops drug war coverage after grenade attacks". Reuters. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ^ "El Manana Newspaper To Stop Covering Certain Stories After Second Grenade Attack". HuffPost. 11 July 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ "Blogger on Mexico cartel beheading: Cannot kill us all". MSN News. 10 November 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d Castillo, Mariano (29 September 2006). "Nuevo Laredo media go silent on violence". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Se incendia casino en Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas". El Universal (in Spanish). 21 May 2012. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ "Consume incendio casino clausurado en Nuevo Laredo". La Jornada (in Spanish). 21 May 2012. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ a b "Incendia el casino Amazonas supuestamente de los Zetas en Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas". Blog del Narco (in Spanish). 21 May 2012. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ "Incendian bar y estalla vehículo en Nuevo Laredo". Animal Politico (in Spanish). 24 May 2012. Archived from the original on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ "Incendian antro y explotan auto en hotel de Nuevo Laredo". Milenio (in Spanish). 24 May 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ "Reportan ataques en Nuevo Laredo". Terra Networks (in Spanish). 24 May 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ "Se incendia discoteca y explota coche bomba en Nuevo Laredo". El Economista (in Spanish). 24 May 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ "Incendian discos y granadean hotel en Nuevo Laredo". Zócalo (in Spanish). 24 May 2012. Archived from the original on 21 August 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ "Nightclubs burned, chaos in the streets of Nuevo Laredo". KGBT-TV. 24 May 2012. Archived from the original on 21 August 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ "Nuevo Laredo Morning Explosion". KGNS-TV. 24 May 2012. Archived from the original on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch