Gezi Park protests

| Gezi Park protests | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Protests on 6 June, with the slogan "Do not submit" | |||

| Date | 28 May – 20 August 2013[1] (2 months, 3 weeks and 3 days) | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by |

| ||

| Goals |

| ||

| Methods | Sit-ins, strike actions, demonstrations, online activism, protest marches, civil disobedience, civil resistance, cacerolazo | ||

| Resulted in |

| ||

| Parties | |||

| Lead figures | |||

Non-centralised leadership Government leaders:

| |||

| Number | |||

| |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 11[67] | ||

| Injuries | at least 8,163 (during the Gezi Park protests)[68] (at least 63 in serious or critical condition with at least 3 having a risk of death)[68] | ||

| Arrested | at least 4,900 with 81 people being held in custody (during the Gezi Park protests)[69][70][71][72][73][74] | ||

| Detained | at least 134 (during the Gezi Park protests)[72][73][74] | ||

A wave of demonstrations and civil unrest in Turkey began on 28 May 2013, initially to contest the urban development plan for Istanbul's Taksim Gezi Park.[75] The protests were sparked by outrage at the violent eviction of a sit-in at the park protesting the plan.[76] Subsequently, supporting protests and strikes took place across Turkey, protesting against a wide range of concerns at the core of which were issues of freedom of the press, of expression and of assembly, as well as the AKP government's erosion of Turkey's secularism. With no centralised leadership beyond the small assembly that organised the original environmental protest, the protests have been compared to the Occupy movement and the May 1968 events. Social media played a key part in the protests, not least because much of the Turkish media downplayed the protests, particularly in the early stages. Three and a half million people (out of Turkey's population of 80 million) are estimated to have taken an active part in almost 5,000 demonstrations across Turkey connected with the original Gezi Park protest.[77] Twenty-two people were killed and more than 8,000 were injured, many critically.[77]

The sit-in at Taksim Gezi Park was restored after police withdrew from Taksim Square on 1 June, and developed into a protest camp, with thousands of protesters in tents, organising a library, medical centre, food distribution and their own media. After the Gezi Park camp was cleared by riot police on 15 June, protesters began to meet in other parks all around Turkey and organised public forums to discuss ways forward for the protests.[78][79] Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan dismissed the protesters as "a few looters" on 2 June.[5] Police suppressed the protests with tear gas and water cannons. In addition to the 11 deaths and over 8,000 injuries, more than 3,000 arrests were made. Police brutality and the overall absence of government dialogue with the protesters was criticised by some foreign governments and international organisations.[1][80]

The range of the protesters was described as being broad, encompassing both right- and left-wing individuals.[5] Their complaints ranged from the original local environmental concerns to such issues as the authoritarianism of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan,[81][82][83] curbs on alcohol,[84] a recent row about kissing in public,[5] and the war in Syria.[5] Protesters called themselves çapulcu (looters), reappropriating Erdoğan's insult for them (and coined the derivative "chapulling", given the meaning of "fighting for your rights"). Many users on Twitter also changed their screenname and used çapulcu instead.[85] According to various analysts, the protests were the most challenging events for Erdoğan's ten-year term and the most significant showing of nationwide disquiet in decades.[86][87]

Background

[edit]

The Justice and Development Party (AKP) led by Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has governed since 2002, winning the 2002, 2007 and 2011 elections by large margins. Under its rule the economy of Turkey recovered from the 2001 financial crisis and recession, driven in particular by a construction boom. At the same time, particularly since 2011, it has been accused of driving forward an Islamist agenda,[88] having undermined the secularist influence of the Turkish Army. During the same period it also increased a range of restrictions on human rights, most notably freedom of speech and freedom of the press, despite improvements resulting from the accession process to the European Union.[89]

Since 2011, the AKP has increased restrictions on freedom of speech, freedom of the press, Internet use,[90] television content,[91] and the right to free assembly.[92] It has also developed links with Turkish media groups, and used administrative and legal measures (including, in one case, a $2.5 billion tax fine) against critical media groups and journalists: "over the last decade the AKP has built an informal, powerful, coalition of party-affiliated businessmen and media outlets whose livelihoods depend on the political order that Erdoğan is constructing. Those who resist do so at their own risk."[93]

The government has been seen by certain constituencies as increasingly Islamist and authoritarian,[94][95][96] An education reform strengthening Islamic elements and courses in public primary and high schools was approved by the parliament in 2012, with Erdoğan saying that he wanted to foster a "pious generation."[97] The sale and consumption of alcohol in university campuses has been banned.[84][98] People have been given jail sentences for blasphemy.[99][100]

While construction in Turkey has boomed and has been a major driver for the economy, this has involved little to no local consultation. For example, major construction projects in Istanbul have been "opposed by widespread coalitions of diverse interests. Yet in every case, the government has run roughshod over the projects' opponents in a dismissive manner, asserting that anyone who does not like what is taking place should remember how popular the AKP has been when elections roll around."[93]

Environmental issues, especially since the 2010 decision of the government to build additional nuclear power plants and the third bridge, led to continued demonstrations in Istanbul and Ankara.[101] The Black Sea Region has seen dozens of protests against the construction of waste-dumps, nuclear and coal power plants, mines, factories and hydroelectric dams.[102] 24 local musicians and activists in 2012 created a video entitled "Diren Karadeniz" ("Resist, Black Sea"), which prefigured the ubiquitous Gezi Park slogan "Diren Gezi".[103]

The government's stance on the civil war in Syria is another cause of social tension in the country.[104]

Controversy within progressive communities has been sparked by plans to turn Turkey's former Christian Hagia Sophia churches (now mosque) in Trabzon and possibly Istanbul into mosques, a plan which failed to gain the support of prominent Muslim leaders from Trabzon.[105][106]

In 2012 and 2013, structural weaknesses in Turkey's economy were becoming more apparent. Economic growth slowed considerably in 2012 from 8.8% in 2011 to 2.2% in 2012 and forecasts for 2013 were below trend. Unemployment remained high at at least 9% and the current account deficit was growing to over 6% of GDP.[citation needed]

A key issue Erdoğan campaigned for prior to the 2011 election was to rewrite the military-written constitution from 1982. Key amongst Erdoğan's demands were for Turkey to transform the role of President from that of a ceremonial role to an executive presidential republic with emboldened powers and for him to be elected president in the 2014 presidential elections. To submit such proposals to a referendum needs 330 out of 550 votes in the Grand National Assembly and to approve without referendum by parliament requires 367 out of 550 votes (a two-thirds majority)—the AKP currently holds only 326 seats. As such the constitutional commission requires agreement from opposition parties, namely the CHP, MHP and BDP who have largely objected to such proposals. Moreover, the constitutional courts have ruled that current president Abdullah Gül is permitted to run for the 2014 elections, who is widely rumoured to have increasingly tense relations and competition with Erdoğan. Furthermore, many members of parliament in the governing AKP have internally also objected by arguing that the current presidential system suffices. Erdoğan himself was barred from running for a fourth term as prime minister in the 2015 general elections due to AKP by-laws, largely sparking accusations from the public that Erdoğan's proposals were stated in light of him only intending to prolong his rule as the most dominant figure in politics. The constitutional proposals have mostly so far been delayed in deliberations or lacked any broad agreement for reforms.

Events leading up to the protests

[edit]- 29 October 2012: The governor of Ankara bans a planned Republic Day march organised by secularist opposition groups. Despite the ban, thousands of people, including the leader of Turkey's largest opposition party CHP gather at Ulus Square. Riot police forces attack the protesters with tear gas and watercannon, despite the fact that there were many children and elderly people in the crowd.[107]

- Early February 2013: The government attempts to make abortion virtually unobtainable.[108] This follows Erdoğan's sparking his campaign against abortion in June 2012, which later saw various protests by feminist groups and individuals.

- 19 February: A survey conducted by Kadir Has University (incorporating up to 20 000 interviewees from 26 of 81 provinces and having a low margin of error) shows considerable disapproval of Erdoğan's strongly advocated proposed change from a parliamentary system to an American-style executive presidential system by 2014—65.8% opposed and 21.2% in support.[109]

- February–March: A large bank in Turkey, Ziraat Bank, changes its name from "T.C. Ziraat Bankası" to simply "Ziraat Bankası", thus omitting the acronym of the Republic of Turkey, T.C., (Türkiye Cumhuriyeti). The Turkish Ministry of Health also stops using T.C. in signs. In protest, thousands of people start using TC in front of their names on Facebook and Twitter as a silent protest. Some people believe that the AKP is trying to change the name or the regime of the country while others believe that this omission of the letters TC is a sign of privatization of the Ziraat bank and hospitals.[citation needed]

- Late March: The Nawroz celebrations were missing the Turkish flag. Many view this as a denigration of the republic. Opposition members of parliament protest by bringing personal flags into the chamber whilst seated.[110]

- 2 April: The AKP's Istanbul branch head, Aziz Babuşçu, broadly hints that he expects his own party to lose liberal support.[111]

- 3 April: Excavation for construction begins for the hugely controversial giant Camlica Mosque in Istanbul.[112] It is a signature policy ambition of Erdoğan—planned to be 57,511 square metres, have capacity for up to 30,000 simultaneous worshipers and to have minarets as tall as 107.1 metres (representing the year of the Turkish victory in the Battle of Manzikert). Residents of Istanbul have long complained that the project is unnecessary and would disfigure the skyline and environment by the logging involved. Even many highly religious lobbies and figures object to the plan, with one religiously conservative intellectual in late 2012 calling such plans a "cheap replica" of the Blue Mosque and wrote to Erdoğan imploring him not to embarrass coming generations with such "unsightly work".[113]

- 15 April: World-renowned Turkish pianist Fazıl Say is handed a suspended 10-month prison sentence for "insulting religious beliefs held by a section of the society," bringing to a close a controversial case while sparking fiery reaction and disapproval in Turkey and abroad.[114] Fazıl Say is an atheist and a self-proclaimed opponent of Erdoğan.[citation needed]

- 1 May: Riot police uses water cannon and tear gas to prevent May Day marchers reaching the Taksim square. The government cites renovation work as the reason for closing the square.[115]

- 11 May: Twin car bombs kill 52 people and wounded 140 in Reyhanlı near the Syrian border.[116] The government claims Syrian government involvement, but many locals blame government policies.[citation needed]

- 16 May: Erdoğan pays an official visit to the United States to visit Barack Obama to discuss the crisis in Syria amidst other matters. Both leaders reaffirm their commitment to topple the Assad regime, despite the growing unpopularity of the policy amongst Turkish citizens.[117]

- 18 May: Protesters clash with police in Reyhanlı.[118]

- 22 May: Turkish hacker group RedHack released secret documents which belongs to Turkish Gendarmerie. According to documents, National Intelligence Organization (Turkey), Turkish Gendarmerie and General Directorate of Security knew the attack would be one month in advance.[119]

- 22 May An official from the ruling AKP, Mahmut Macit, sparks considerable controversy after calling for the "annihilation of atheists" on his Twitter account.[120]

- Armenian-Turkish writer, Sevan Nişanyan, is charged with 58 weeks in jail for an alleged insult to the Islamic prophet, Muhammad in a blog post, under similar charges to those Fazil Say was charged with.[121]

- 24 May: The government votes to ban the sale of alcohol in shops between 22:00 and 06:00, sponsorship of events by drinks companies and any consumption of alcohol within 100m of mosques. The laws are passed less than two weeks after public announcement with no public consultation.[122]

- 25 May: In response to Erdoğan's warning against couples displaying romantic displays of affection in public, dozens of couples gathered in an Ankara subway station to protest by kissing. The police quickly intervened and violently tried to end it.[123]

- 27 May: The undebated decision to name the Third Bosphorus Bridge Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge, for Selim I, is criticised by Alevi groups (some 15–30% of Turkey's population), as Alevis consider the Sultan responsible for the deaths of dozens of Alevis after the Battle of Chaldiran.[124] It is also been criticised by some Turkish and foreign sources (e.g., Iran's Nasr TV) as a reflection of Erdoğan's policy of alliance with the US Government against Bashar Assad, as Sultan Selim I conquered the lands of Syria for the Ottoman Empire after the Battle of Marj Dabiq.[125] Some "democrats and liberals" also would have preferred a more politically neutral name, with Mario Levi suggesting naming the bridge after Rumi or Yunus Emre.[126]

- 28 May Erdoğan derides controversy regarding alcohol restrictions stating "Given that a law made by two drunkards is respected, why should a law that is commanded by religion be rejected by your side". By many, this is seen as a reference to Atatürk and İnönü, founders of the Turkish Republic.[127]

- 29 May: In a parliamentary debate, the government opposes a proposed extension of LGBT rights in Turkey.[128]

Gezi Park

[edit]

The initial cause of the protests was the plan to remove Gezi Park, one of the few remaining green spaces in the center of the European side of Istanbul. The plan involved pedestrianising Taksim Square and rebuilding the Ottoman-era Taksim Military Barracks, which had been demolished in 1940.[129] Development projects in Turkey involve "cultural preservation boards" which are supposed to be independent of the government, and in January such a board rejected the project as not serving the public interest. However a higher board overturned this on 1 May, in a move park activists said was influenced by the government.[130] The ground floor of the rebuilt barracks was expected to house a shopping mall, and the upper floors luxury flats, although in response to the protests the likelihood of a shopping mall was downplayed, and the possibility of a museum raised.[131][132] The main contractor for the project is the Kalyon Group, described in 2013 by BBC News as "a company which has close ties with the governing AKP."[133]

The Gezi Park protests began in April, having started with a petition in December 2012.[134] The protests were renewed on 27 May, culminating in the creation of an encampment occupying the park. A raid on this encampment on 29 May prompted outrage and wider protests.[135][better source needed] Although Turkey has a history of police brutality, the attack on a peaceful sit-in by environmentalists was different enough to spur wider outrage than such previous incidents, developing into the largest protests in Turkey in decades.[136][137]

The large number of trees that were cut in the forests of northern Istanbul for the construction of the Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge (Third Bosphorus Bridge) and the new Istanbul Airport[138][139][140][141] (the world's largest airport, with a capacity for 150 million passengers per year)[138][140][142] were also influential in the public sensitivity for protecting Gezi Park. According to official Turkish government data, a total of 2,330,012[143][144] trees have been cut for constructing the Istanbul International Airport and its road connections; and a total of 381,096[143][144] trees have been cut for constructing the highway connections of the Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge;[143][144] reaching an overall total of 2,711,108[143][144] trees which were cut for the two projects.[143][144][145]

Timeline

[edit]

- 2013 May On the morning of 28 May, around 50 environmentalists are camping out in Gezi Park in order to prevent its demolition.[146] The protesters initially halt attempts to bulldoze the park by refusing to leave.[146][147]

Police use tear gas to disperse the peaceful protesters and burn down their tents in order to allow the bulldozing to continue.[147] Photos of the scene, such as an image of Ceyda Sungur, a young female protester (later nicknamed the "woman in red") holding her ground while being sprayed by a policeman, quickly spread throughout the world media.[148] The Washington Post reports that the image "encapsulates Turkey's protests and the severe police crackdown", while Reuters calls the image an "iconic leitmotif."[citation needed]

The size of the protests grows.[149]

Police raid the protesters' encampments.[150] Online activists' calls for support against the police crackdown increase the number of sit-in protesters by the evening.[151]

Police carry out another raid on the encampment in the early morning of 31 May, using water cannons and tear gas to disperse the protesters to surrounding areas[152] and setting up barricades around the park to prevent re-occupation.[152] Throughout the day, the police continue to fire tear gas, pepper spray and water cannons at demonstrators, resulting in reports of more than 100 injuries.[153] MP Sırrı Süreyya Önder and journalist Ahmet Şık were hospitalised after being hit by tear gas canisters.[154]

The executive order regarding the process decided earlier had been declared as "on-hold".[155]

10,000 gather in Istiklal Avenue.[156] According to governor Hüseyin Avni Mutlu, 63 people are arrested and detained.[157][158] Police use of tear gas is criticised for being "indiscriminate."[157] The interior minister, Muammer Guler, says the claims of the use of disproportionate force would be investigated.[157]

- 2013 June Heavy clashes between protesters and police continue until early morning around İstiklal Avenue. Meantime, around 5,000 people gather at the Asian side of Istanbul and march through Kadıköy Bağdat Avenue. Around 1,000 people continue to march towards the European side and they cross the Bosphorus Bridge on foot. Protesters reach Beşiktaş in the morning and police disperse them with tear gas.[159]

Clashes continue throughout the day. Republican People's Party leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu announce that they will move their planned rally to Taksim Square instead of Kadıköy. Prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan says he has approved that decision.[160] Around 15:45 police forces retreat from Taksim Square. Thousands of protesters gather at Gezi Park and Taksim Square.[161]

Protester Ethem Sarısülük gets shot in the head by a riot policeman during the protests at Ankara Kizilay Square. He dies 14 days later due to his injuries.[162]

PM Recep Tayyip Erdoğan describes the protesters as "a few looters" in a televised interview. He also criticises social media, calling Twitter a "menace" and an "extreme version of lying".[163]

At night, police forces try to disperse protesters gathered at Beşiktaş district. Clashes between police and protesters continue until next morning. Beşiktaş football team supporter group Çarşı members hijack a bulldozer and chase police vehicles.[164]

Front side of AKM (Atatürk Cultural Center) building at Taksim Square gets covered with banners.

In Ankara, police tries to disperse thousands of protesters who are attempting to march on the prime minister's office there.[162]

PM Recep Tayyip Erdoğan speaks to reporters at the airport before leaving for a three-day trip to North Africa. He threatens the protesters saying "We are barely holding the 50 percent (that voted for us) at home."[165]

Turkey's deputy prime minister Bulent Arinc offers an apology to protesters.[166]

22-year Abdullah Cömert dies after being hit in the head by tear gas canister during the protests at Hatay.[167][168]

PM Recep Tayyip Erdoğan speaks to his supporters outside of Istanbul Atatürk Airport on his return from a four-day trip to North Africa. Erdoğan blames "interest rate lobbies" claiming they are behind Gezi protests. His supporters chant "Give us the way, we will crush Taksim Square".[169]

Riot police forces enter Taksim square early in the morning. They make announcements that they will not be entering Gezi Park and their mission is to open Taksim Square to traffic again. Most protesters gather at Gezi Park, but a small group carrying banners of the Socialist Democracy Party retaliate using molotov cocktails and slingshots.[170] Some people like Luke Harding from The Guardian claims that undercover police threw molotov cocktails, "staging a not very plausible 'attack' on their own for the benefit of the cameras."[171][172] These claims were rejected by the governor of Istanbul, Hüseyin Avni Mutlu.[173]

After police tries to enter Gezi park, clashes continue throughout the night and CNN International makes an eight-hour live coverage.[174] Pro-government media accuses CNN and Christiane Amanpour of deliberately showing Turkey in a state of civil war.[175]

PM Recep Tayyip Erdoğan holds a meeting with the members of Taksim Solidarity in Ankara.[176] When a member says that those protests have a sociological aspect, he gets angry and leaves the meeting saying "We are not going to learn what sociology is from you!".[177]

Justice and Development Party organises a mass rally called "Respect to National Will" in Ankara. Talking at the rally, PM Recep Tayyip Erdoğan says that "If protesters don't move out of Gezi Park, police forces will intervene".[178]

At about 17:30, police forces begin making announcements to protesters telling to leave Gezi Park. Police forces make an assault about 20:50 and clear Gezi Park. Protesters move to areas around İstiklal Street and clash with police.[179]

Meanwhile, about 5,000 protesters gather at the Asian side of Istanbul and begin marching towards the European side. Riot police forces disperse the protesters with tear gas before reaching the Bosphorus Bridge.[180]

Heavy clashes between police and protesters continue until morning at various parts of Istanbul.[181]

Justice and Development Party organises its second rally at Istanbul Kazlıçeşme Square.[182]

A general strike and protests organised by five trade unions take place in almost every part of Turkey. Strikes doesn't have any negative effect on the daily life which led criticism of unions and their power.[183]

The "Standing Man", Erdem Gündüz starts his silent protest in the evening.[184] Similar protests consisting of simply stopping and standing still spread everywhere in Turkey.[185][186]

President Abdullah Gül announces suspension of Gezi Park redevelopment plans.[187]

An investigation regarding police brutality is opened and some officers dismissed.[188][189]

Violence and mass demonstrations spread again in the country, after police attacks on thousands of protesters who threw carnations at them and called for brotherhood.[190] Mass demonstrations occur again in Taksim Square, Istanbul and also in Güvenpark and Dikmen in Ankara to protest against the release of police officer Ahmet Şahbaz who fatally shot Ethem Sarısuluk in the head, as well as against events in Lice, Diyarbakır and Cizre, Şırnak. Riot police suppress the protesters partially with plastic bullets and some tear gas bombs and some protesters are detained. There is also a major police intervention in Ankara.[191] The Istanbul LGBT Pride 2013 parade at Taksim Square attracts almost 100,000 people.[192] Participants were joined by Gezi Park protesters, making the 2013 Istanbul Pride the biggest pride ever held in Turkey and eastern Europe.[193] The European Union praises Turkey that the parade went ahead without disruption.[194]

- 2013 July A machete-wielding man attacks the Gezi park protesters at Taksim Square. He is detained by the police, but gets released the same day.[195] After being released, he flees to Morocco on 10 July.[196]

Thousands of people stage the "1st Gas Man Festival" (1. Gazdanadam Festivali) in Kadıköy to protest against the police crackdown on anti-government and nature-supporting demonstrations across the country.[197] With the arrival of Ramadan, protesters in Istanbul hold mass iftar (the ceremonial meal breaking the daily fast) for all comers.[198] 19-year-old Ali İsmail Korkmaz, who was in a coma since 4 June dies.[199] He was severely battered by a group of casually dressed people on 3 June while running away from police intervention.[200]

- 2013 August The scale and frequency of demonstrations dies down in the summer. Human chains are organised for peace and against intervention in Syria.[201] Protesters begin painting steps in rainbow colours.[202]

Protesters

[edit]The initial protests in Istanbul at the end of May were led by about 50 environmentalists,[203] opposing the replacement of Taksim Gezi Park with a shopping mall and possible residence[136] as well as reconstruction of the historic Taksim Military Barracks (demolished in 1940) over the adjacent Taksim Square.[204] The protests developed into riots when a group occupying the park was attacked with tear gas and water cannons by police. The subjects of the protests then broadened beyond the development of Taksim Gezi Park into wider anti-government demonstrations.[94][205] The protests also spread to other cities in Turkey, and protests were seen in other countries with significant Turkish communities, including European countries, the U.S. and elsewhere.[206] Protesters took to Taksim Square in Istanbul and to streets in Ankara[3] as well as İzmir, Bursa, Antalya, Eskişehir, Balıkesir, Edirne, Mersin, Adana, İzmit, Konya, Kayseri, Samsun, Antakya,[207] Trabzon, Isparta, Tekirdağ, Bodrum,[5] and Mardin.[63]

The overall number of protesters involved was reported to be at least 2.5 million by the Turkish Interior Ministry over the 3 weeks from the start of the events.[208] The hashtag #OccupyGezi trended in social media.[209] On 3 June unions announced strikes for 4 and 5 June.[210] Some Turkish-American supporters of the protests took a full-page advertisement in The New York Times on 7 June co-created and crowd-funded within days by thousands of people on the Internet.[211] The ad and The New York Times drew criticism from the Turkish Prime Minister, necessitating the newspaper to respond.[212]

The range of the protesters was noted as being broad, encompassing both right and left-wing individuals.[5][23] The Atlantic described the participants as "the young and the old, the secular and the religious, the soccer hooligans and the blind, anarchists, communists, nationalists, Kurds, gays, feminists, and students."[33] Der Spiegel said that protests were "drawing more than students and intellectuals. Families with children, women in headscarves, men in suits, hipsters in sneakers, pharmacists, tea-house proprietors – all are taking to the streets to register their displeasure."[213] It added that there was a notable absence of political party leadership: "There have been no party flags, no party slogans and no prominent party functionaries to be seen. Kemalists and communists have demonstrated side-by-side with liberals and secularists."[213] Opposition parties told members not to participate, leaving those who joined in doing so as private individuals.[214]

- Gezi Park protesters

- Protesters applaud a whirling Sufi wearing a gas mask.

- Many women in headscarves attended the protests, despite the fact that pro-AKP media spread disinformation that they were being attacked by the protesters.

- A banner in Kurdish in Gezi Park during protests remembering the Assassination of Hrant Dink, a prominent Turkish-Armenian journalist: "For Hrant, For Justice (Ji Bo Hrant, Ji Bo Dade ê)"

In a country like Turkey, where people state they occasionally feel divided due to their socio-economic status, race, and religion, the major unifying power has always been sports, more specifically, football.[215] The three most prominent and historic soccer clubs of Turkey are Galatasaray, Fenerbahçe and Beşiktaş.[215] Between these three Istanbul clubs, the rivalry is so fierce that Turkish Armed Forces get involved in securing the fields during derby days.[216] For the most passionate fans, accepting a handshake from the opposing team would seem to be an unthinkable feat.[216] However, this was all set aside during the Gezi Parkı protests.[217] Many were outraged after the invasion of the park in Taksim Square, so the ultras of Galatasaray, Fenerbahçe, and Beşiktaş came together to protest the incident.[218] The fans held hands and shouted as they would in a stadium with their usual fanatic chants; but, this time against President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the police forces.[215] Millions of Turkish football fans poured the streets of Istanbul and generated a march of unity.[219] The surprising harmony of these fans was so powerful that it contributed majorly for President Erdogan to shift some of his views on the subject matter.[217] It was a testament to both the power of protest and the coming together of people with differing views.[220]

The Guardian observed that "Flags of the environmentalist movement, rainbow banners, flags of Atatürk, of Che Guevara, of different trade unions, all adorn the Gezi park."[221] Flag of PKK and its leader Abdullah Öcalan's posters and were also seen.[222] The Economist noted that there were as many women as men, and said that "Scenes of tattooed youths helping women in headscarves stricken by tear gas have bust tired stereotypes about secularism versus Islam."[223] Across political divides, protesters supported each other against the police.[224]

According to Erdoğan's 4 June speech from Morocco, the demonstrators are mostly looters, political losers and extremist fringe groups. He went on to say they went hand-in-hand with 'terrorists' and 'extremists'.[225] He indicated that these protests were organised by the Republican Peoples Party (even though the CHP had initially supported construction on the Gezi-park). Turkey analysts however suggested the demonstrations arose from bottom-up processes, lacking leadership.[226]

A Bilgi University survey asked protesters about events that influenced them to join in the protests. Most cited were the prime minister's "authoritarian attitude" (92%), the police's "disproportionate use of force" (91%), the "violation of democratic rights" (91%), and the "silence of the media" (84%).[6] Half the protesters were under 30, and 70% had no political affiliation;[227] another poll found 79% had no affiliation with any organisation.[228]

Demands

[edit]On 4 June a solidarity group associated with the Occupy Gezi movement, Taksim Dayanışması ("Taksim Solidarity"), issued several demands:[229]

- the preservation of Gezi Park;

- an end to police violence, the right to freedom of assembly and the prosecution of those responsible for the violence against demonstrators;

- an end to the sale of "public spaces, beaches, waters, forests, streams, parks and urban symbols to private companies, large holdings and investors";

- the right of people to express their "needs and complaints without experiencing fear, arrest or torture."

- for the media "whose professional duty is to protect the public good and relay correct information ... to act in an ethical and professional way."[13]

- ruling authorities to realise that the reaction of the citizens is also about the third airport in Istanbul, the third bridge over The Bosporus, the construction on Atatürk Forest Farm, and the hydro-electric power plants (HEPP)[230]

Deputy Prime Minister Bülent Arınç met the group on 5 June but later rejected these demands.[231]

Types of protest

[edit]Gezi Park camp

[edit]

With the police abandoning attempts to clear the Gezi Park encampment on 1 June, the area began to take on some of the characteristics associated with the Occupy movement.[232] The number of tents swelled, to the point where a hand-drawn map was set up at the entrance.[233] Access roads to the park and to Taksim Square have been blocked by protesters against the police with barricades of paving stones and corrugated iron.[234]

By evening on 4 June there were again tens of thousands in Taksim Square; Al Jazeera reported that "there are many families with their children enjoying the demonstration that has developed the feeling of a festival."[235] There were also signs of a developing infrastructure reminding some observers of Occupy Wall Street, with "a fully operational kitchen and first-aid clinic... carved out of an abandoned concession stand in the back of the park," complete with rotas and fundraising for people's travel expenses.[236] Protesters brought food to donate, and dozens of volunteers organised themselves into four shifts.[227]

A makeshift "protester library" was also created (soon reaching 5000 books[237]),[238][239] and Şebnem Ferah gave a concert.[240] A "makeshift outdoor movie screen" was set up,[227] together with a stage with microphones and speakers, and a generator.[233] A symbolic "street" was named after Hrant Dink, the journalist murdered in 2007; the street connects the Peace Square with the children's playground.[241] Sellers of watermelons mingled with sellers of swimming goggles and surgical masks (to protect against tear gas) and a yoga teacher provided classes. The crowds swelled in the evening as office workers joined.[242]

With 5 June being the Lailat al Miraj religious holiday, protesters distributed "kandil simidi" (a pastry specific to the holiday), and temporarily declared the park a no-alcohol zone. Celebration of the holiday included a Quran reading.[243]

Peter Gelderloos argued that the camp was a small, anarchist community that heavily emphasized mutual aid. He also argued that large cultural change occurred within the camp. He argued that the Gezi Park was one of the most successful examples of social activism in recent history, mainly due to its refusal to be represented by political parties, trade unions and the media.[244]

Symbols and humour

[edit]

One photograph taken by Reuters photographer Osman Orsal of a woman in a red dress being pepper-sprayed became one of the iconic images of the protests: "In her red cotton summer dress, necklace and white bag slung over her shoulder she might have been floating across the lawn at a garden party; but before her crouches a masked policeman firing teargas spray that sends her long hair billowing upwards."[245][246] Orsal himself was later injured by a tear gas canister.[135][better source needed] In June 2015 the police officer who sprayed pepper gas in the face of "the woman in red" was sentenced to 20 months in jail and to plant 600 trees by a criminal court in Istanbul.[247]

Guy Fawkes masks have also been widely used, for example by striking Turkish Airlines cabin crew performing a parody of airline safety announcements referring to the protests.[248]

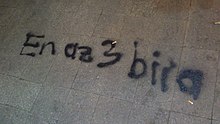

The protesters have also made significant use of humour, both in graffiti and online, in what BBC News called "an explosion of expression... in the form of satire, irony and outright mockery of the popular leader on Istanbul's streets and social media." It gave as an example a parody of the Turkish auction site sahibinden.com as "tayyibinden.com", listing Gezi Park for sale.[249] Examples of slogans include "Enough! I'm calling the police", as well as pop culture references: "Tayyip – Winter is Coming" (a reference to Game of Thrones) and "You're messing with the generation that beats cops in GTA" (a reference to Grand Theft Auto).[250][251][252]

Protesters had previously mocked Erdoğan's recommendation to have at least three children and policy of restricting alcohol with the slogan "at least 3 beers" even though this is criticised on social media for Erdoğan's recommendation of having three children is his personal view and not a government policy.

Penguins were also adopted as a symbol, referring to CNN Turk's showing a penguin documentary while CNN International provided live coverage of the protests; examples include "We are all penguins" T-shirts.[253][254]

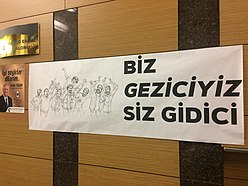

In response to Erdoğan's description of the protesters as looters (üç beş çapulcu, "a few [literally: three to five] looters"), demonstrators took up the name as a symbol of pride, describing their peaceful and humorous civil disobedience actions as chapulling.[255][256] A majority of social-media users participating in the protests also changed their Twitter screen names after Erdogan calling them looters, adding çapulcu as if a professional title.[85]

Other parks and public forums

[edit]

Encampments were made in other parks in support of the Gezi protests, including in Ankara's Kuğulu Park[257] and in Izmir's Gündoğdu Square.[258]

After the violent clearing of Gezi Park on 15–16 June by riot police and Turkish Gendarmerie, Beşiktaş JK's supporter group Çarşı, declared the Abbasağa Park, in Beşiktaş district as the second Gezi Park and called for people to occupy it on 17 June.[259] After this call, thousands started to gather at Abbasağa Park, holding public forums to discuss and vote on the situation of the resistance and actions to be taken. Shortly after this, democracy forums and meetings spread to many parks in Istanbul and then to the other cities, like Ankara, Izmir, Mersin, etc.[260][261]

Graduations

[edit]As the protests mostly took place on the beginning of summer, on the time all schools makes their students graduate, the protests and humour have hit hundreds of universities' and high schools' graduations too.

Stadiums

[edit]As many fan associations from various parts of Turkey supported and participated in protests actively on the ground and also supported the resistance against the AKP government and its various policies, in the stadiums with their chants, clothes, slogans, banners and posters, the stadiums became practical places of Gezi protests and where fans can do even more political expressions than before, mostly opposing to the government and its ideologies. As this continued to happen during the off-season friendly and continental trophy matches, the government took many precautions with an organising law for stadiums that passed from the assembly with AKP votes, banning to bring politics into stadiums, but soon after the start of the Turkish sports leagues, as most of the fans continued to their protests, this time even more organised and loud, first punishments on the opposing fans and clubs were given, but there was much criticism both from Turkish and foreigner experts about the law banning bringing "opposition" into stadiums, not "politics", as some fan groups opened banners that openly support AKP in Konya and supported Morsi of Egypt in Bursa.

Demonstrations and strikes

[edit]

Demonstrations were held in many cities in Turkey. According to the Human Rights Foundation of Turkey around 640,000 people had participated in the demonstrations as of 5 June.[262] Protests took place in 78 of Turkey's 81 provinces.[263] The biggest protests have been in Istanbul, with reports of more than 100,000 protesters.[207][264] Inside of the city, protests have been concentrated in the central neighbourhoods of Beyoğlu (around Taksim square and İstiklal Avenue), Beşiktaş (from Dolmabahçe to Ortaköy) and Üsküdar (From Maltepe to Kadıköy, Beylerbeyi to Çengelköy). Also in Zeytinburnu, traditionally seen as a conservative working-class neighbourhood to the west of the old city, tens of thousands marched in protest. Among the suburbs that saw demonstrations were Beylikdüzü and Küçükçekmece on the far-western side of the city, Pendik and Kartal at the far east and Ümraniye, Beykoz and Esenler to the North.

Gazi (not to be confused with Gezi Park), a small neighborhood in Istanbul and part of the Sultangazi district, was one of the major points of counter-protests.

The biggest protests outside Istanbul have been in Hatay and then in Ankara and Izmir.[62][265] Other cities in Turkey with protests include (Between 31 May – 25 June):

Other cities outside Turkey with protests include:

Geo-spatial analysis of protest shows support from all over the world and mainly concentrated in Turkey, Europe and East coast of US.[85]

Advertising and petition

[edit]

Within 24 hours on 3 June, a New York Times advertisement led by Murat Aktihanoglu surpassed its $54,000 crowd-funding target on Indiegogo. The ad featured demands for "an end to police brutality"; "a free and unbiased media"; and "an open dialogue, not the dictate of an autocrat."[211][287][288] An early draft sparked debate among Gezi protesters for its references to Atatürk, which was not a common value of the protesters.[289] The editing of the final advertisement involved thousands of people, and the ad was published on 7 June. Despite its financing by 2,654 online funders, Erdoğan and his administration blamed a domestic and foreign "bond interest lobby" and The New York Times for the ad. Full Page Ad for Turkish Democracy in Action: OccupyGezi for the World

An Avaaz petition similarly asked for an end to violence against protesters, the preservation of Gezi Park, and of "the remaining green areas in Istanbul."

On 24 July, drafted and spearheaded by a British film producer Fuad Kavur, an open letter to Turkish PM Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was published in the London Times, as a full-page advertisement. It condemned the Turkish authorities for the heavy-handed crackdown, leaving eight dead and many permanently blinded by indiscriminate use of tear gas.[290] The co-signatories included Sean Penn, Susan Sarandon, Ben Kingsley, David Lynch, and Atatürk's biographer, Andrew Mango.[291] PM Recep Tayyip Erdoğan accused The Times of "renting out its pages for money", and threatened to sue the newspaper.[292]

Standing Man/Woman protest

[edit]

After the clearing of Gezi Park camp on 15 June a new type of protest developed, dubbed the "Standing Man" or "Standing Woman". A protester, Erdem Gündüz, initiated it on 17 June 2013 by standing in Taksim Square for hours, staring at the Turkish flags on the Atatürk Cultural Center. The Internet distributed images of such protest widely; other persons imitated the protest style and artists took up the theme.[293] A type of dilemma action, the initial Standing Man protest soon inspired others to do the same.[294] The Human Rights Foundation announces 2 May the recipients of the 2014 Václav Havel Prize for Creative Dissent. The 2014 laureates are Turkish performance artist Erdem Gündüz together with Russian punk protest group Pussy Riot.[295]

Boycott

[edit]An additional form of protest developed under the name "Boykot Listesi", as a boycott of businesses which had failed to open their doors to protesters seeking refuge from tear gas and water cannon, and of companies such as Doğuş Holding (owner of NTV) which owned media that had not given sufficient coverage of the protests.[296] The hashtag #boykotediyoruz was used.[297]

Violence and vandalism

[edit]

Even though protests were definitely peaceful in the first days and were generally so but in some occasions, there were accusations of violence and vandalism as the protests continued. According to the journalist Gülay Göktürk, "the Gezi Park protesters damaged 103 police cruisers, 207 automobiles, 15 ambulances and 280 buildings and buses in demonstrations across the country."[298] though no other sources confirm these figures.

Responses

[edit]Government response

[edit]On 29 May, after the initial protests, Erdoğan gave a speech at the groundbreaking ceremony for the Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge reiterating his commitment to the redevelopment plan, saying "Whatever you do, we've made our decision and we will implement it."[299] On 31 May Istanbul mayor Kadir Topbaş stated that the environmental campaign had been manipulated by "political agendas."[157]

On 1 June Erdoğan gave a televised speech condemning the protesters and vowing that "where they gather 20, I will get up and gather 200,000 people. Where they gather 100,000, I will bring together one million from my party."[300] On 2 June he described the protesters as "çapulcular" ("looters").[301]

On 1 June Deputy Prime Minister Bülent Arınç criticised the use of tear gas against demonstrators and stated, "It would have been more helpful to try and persuade the people who said they didn't want a shopping mall, instead of spraying them with tear gas."[302] On 4 June an official tweet summarising new comments by Arınç said "We have been monitoring the non-violent demonstrations with respect."[303] Arınç later apologised for use of "excessive force."[231]

On 2 June it was reported that Turkey's President Abdullah Gül contacted other senior leaders urging "moderation." After the call, Interior Minister Muammer Güler ordered police to withdraw from Taksim, allowing protesters to re-occupy the square.[304] On 3 June Gül defended the right to protest, saying that "Democracy does not mean elections alone."[305]

On 4 June Deputy Prime Minister for the Economy Ali Babacan "said the government respects the right to non-violent protest and free speech, but that it must also protect its citizens against violence."[231]

On 8 June "We are definitely not thinking of building a shopping mall there, no hotel or residence either. It can be... a city museum or an exhibition center," Istanbul mayor Kadir Topbas told reporters.[306]

In a press release on 17 June, Egemen Bağış, Minister For EU Affairs, criticised "the use of the platform of the European Parliament to express the eclipse of reason through disproportionate, unbalanced and illogical statements..." and said that "Rather than allowing this, it would be wiser for the EU officials to put an end to it."[307]

3 July, cancellation of the planned construction, in Taksim area, that sparked the protests was finally made public. The court order was made in mid-June at the height of the protest but inexplicably not released for weeks.[204]

Erdoğan gave a number of speeches dismissing the protesters,[308][309] and on 3 June left the country on a planned three-day diplomatic tour of North African countries, a move that was criticised as irresponsible by opposing political leaders. On 4 June, Deputy Prime Minister Bülent Arınç apologised to protesters for "excessive violence" used by the police in the beginning of the riots, but said he would not apologise for the police violence that came after.[310][311] On 6 June, PM Erdoğan said the redevelopment plans would go ahead despite the protests.[312]

Conspiracy claims

[edit]The government has claimed that a wide variety of shadowy forces were behind the protests. In a speech on 18 June, Erdoğan accused "internal traitors and external collaborators", saying that "It was prepared very professionally... Social media was prepared for this, made equipped. The strongest advertising companies of our country, certain capital groups, the interest rate lobby, organisations on the inside and outside, hubs, they were ready, equipped for this."[313] Erdoğan implicitly included the main opposition CHP in the category of "internal traitors", claiming that three-quarters of protest participants had voted for the CHP,[n 1] and accusing CHP leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu "of acting like the head of a terrorist organisation by calling on the police not to obey orders."[313] Erdoğan also claimed that Taksim protests were linked to the Reyhanlı bombings,[314] and accused the CHP of complicity in the bombings, calling on Kılıçdaroğlu to resign.[315]

In late June it was announced that the National Intelligence Organisation was investigating foreign elements in the protests. The Foreign Ministry also demanded "a report detailing which efforts these countries took to create a perception against Turkey, which instruments were used in this process, what our embassies did and what were our citizens' reactions".[316]

Pro-AKP newspapers reported that the protests were planned by the Serbian civil society organisation Otpor!.[317][318]

Yeni Şafak newspaper claimed that a theatre play called "Mi Minor," allegedly supported by an agency in Britain, had held rehearsals of "revolution" in Turkey for months.[319]

Ankara mayor Melih Gökçek accused Selin Girit, a BBC Turkey correspondent of being a spy.[320]

On 1 July, Deputy Prime Minister Besir Atalay accused foreign agents and the Jewish diaspora of orchestrating the protests. "There are some circles that are jealous of Turkey's growth," Atalay said. "They are all uniting, on one side the Jewish Diaspora. You saw the foreign media's attitude during the Gezi Park incidents; they bought it and started broadcasting immediately, without doing an evaluation of the [case]." A number of Turkish commentators and lower-level officials have accused Jewish groups and others of conspiring to engineer the protests and bring about Erdoğan's downfall.[321] On 2 July, the Turkish Jewish Community made a statement that this was an unfounded anti-Semitic generalization.[322]

AKP lawmaker and PM Burhan Kuzu accused Germany of being behind the Gezi protests to stop construction of Istanbul's third airport. He stated that "When it is completed, Frankfurt Airport in Germany will lose its importance. Hence, in the recent Gezi incidents, Germany, along with agents, has a major role."[323]

Mehmet Eymür, a retired officer from Turkish National Intelligence Organisation claimed that Mossad was behind Gezi protests. During a televised interview at one of the pro-government television channels, he stated that some Turkish Jews who did their military service in Israel were Mossad agents and active during Gezi protests.[324]

On 18 October 2017 Turkish philanthropist Osman Kavala was arrested without charge at Istanbul Atatürk Airport when returning from a meeting in Gaziantep.[325] On 4 March 2019, more than 500 days later, during which Kavala remained imprisoned, a criminal indictment seeking life imprisonment for Kavala and 15 other people, including journalist Can Dündar and actor Memet Ali Alabora, was accepted by the Istanbul 30th Heavy Penal Court.[326] The indictment accuses the defendants of forming the mastermind behind the scenes of the Gezi Park protests, which the indictment describes as an "attempt to overthrow the government through violence".[327] The indictment also alleges that philanthropist George Soros was behind the conspiracy.[328] The trial is scheduled to begin on 24 June 2019 with a five-day hearing in the Silivri courthouse of Istanbul.[329]

Police response

[edit]

Protests intensified after (on the morning of 30 May) undercover police burnt the tents of protesters who had organised a sit-in at Gezi Park.[330] Çevik Kuvvet riot police internal messages compared the events to the 1916 Gallipoli Campaign.[331] Amnesty International said on 1 June that "It is clear that the use of force by police is being driven not by the need to respond to violence – of which there has been very little on the part of protesters – but by a desire to prevent and discourage protest of any kind."[332] By 14 June 150,000 tear gas cartridges and 3000 tons of water had been used.[333] In mid-June Amnesty International said that it had "received consistent and credible reports of demonstrators being beaten by police during arrest and transfer to custody and being denied access to food, water, and toilet facilities for up to 12 hours during the current protests in Istanbul which have taken place for almost three weeks."[334] Hundreds of protesters were detained.

As protests continued in early June, tear gas was used so extensively that many residents of central Istanbul had to keep windows closed even in the heat of summer, or use respirators and then struggle to decontaminate homes of tear gas residue.[335] Police even water cannoned a man in a wheelchair.[336] The Turkish Doctors' Association said that by 15 June, over 11,000 people had been treated for tear gas exposure, and nearly 800 for injuries caused by tear gas cartridges.[337] On the weekend of 15 June, police action escalated significantly. Police were seen adding Jenix Pepper Spray to their water cannons,[338][339] and the Istanbul Doctors Association later said that there was "a high but an unknown number of first and second-degree burn injuries because of some substance mixed in pressurised water cannons".[340] On the night of 15/16 June police repeatedly tear-gassed the lobby of the Divan Istanbul hotel, where protesters had taken refuge,[341] causing a pregnant woman to miscarry.[342] They also water-cannoned and tear gassed the Taksim German Hospital.[343][344][345]

Doctors and medical students organised first aid stations. In some cases the stations and medical personnel were targeted by police with tear gas, and one medical student volunteer was left in intensive care after being beaten by police, despite telling them that he was a doctor trying to help. Medical volunteers were also arrested. "[Police] are now patrolling the streets at night and selectively breaking ground-floor windows of apartments and throwing tear gas into people's homes. They have been joined by groups of AKP sympathisers with baseball bats."[346] One volunteer medic working at a tent in Taksim Square said that "They promised us that they would not attack our field hospital, but they did anyway, firing six rounds of teargas directly into our tent."[347]

Lawyers were also targeted by police. On 11 June at least 20 lawyers gathering at the Istanbul Çağlayan Justice Palace to make a press statement about Gezi Park were detained by police, including riot police.[348] The arrests of total 73–74 lawyers were described as "very brutal and anti-democratic" by one lawyer present, with many injured: "They even kicked their heads, the lawyers were on the ground. They were hitting us they were pushing. They built a circle around us and then they attacked."[349]

There were also reports of journalists being targeted by police.[350][351] The New York Times reported on 16 June that "One foreign photographer documenting the clashes Saturday night said a police officer had torn his gas mask off him while in a cloud of tear gas, and forced him to clear his memory card of photographs."[352][353] Reporters without Borders reported eight journalists arrested, some violently, and several forced to delete photographs from their digital cameras.[354]

A spokesman for the police union Emniyet-Sen said poor treatment of officers by the police was partly to blame for the violence: "Fatigue and constant pressure lead to inattentiveness, aggression and a lack of empathy. It's irresponsible to keep riot police on duty for such long hours without any rest."[355]

On 2 October, the Amnesty International released a full report about police brutality at Gezi Park protests with the title of "Gezi Park Protests: Brutal Denıal of the Rıght To Peaceful Assembly in Turkey".[1]

On 16 October, the European Union released its progress report on Turkey, with Gezi protests putting a mark on crucial parts of the document. Report stated that "The excessive use of force by police and the overall absence of dialogue during the protests in May/June have raised serious concerns".[80]

On 26 November, commissioner for human rights of the Council of Europe released a full report about Turkey and Gezi protests.[1] The report said that "The Commissioner considers that impunity of law-enforcement officials committing human rights violations is an entrenched problem in Turkey".[356]

Counter-movements

[edit]Although in most cities there were no counter-protests during the first week, some cities (e.g. Konya) saw minor disagreements and scuffles between nationalists and left-wing groups.[357] When a small group of people wanted to read a statement in front of Atatürk's statue in Trabzon's central Meydan/Atatürk square another small group of far-right nationalists chased them off, the police separated the groups to prevent violence.[358] Nonetheless, during day and night time there were marches and other kinds of protests in the city, but mostly without political banners.

Lists of prominent individuals who had supported the protests (e.g. actor Memet Ali Alabora) were circulated,[359] and images of protest damage circulated under the heading #SenOde ("You pay for it"). The daily Yeni Şafak criticised prominent government critics such as Ece Temelkuran, with a piece on 18 June headlined "Losers' Club".[360]

Hasan Karakaya, an author of the pro-AKP newspaper Akit, wrote about the events going on in Turkey, finding them similar to the latest situation in Egypt, and used the terms "dog" (köpek), "pimp" (pezevenk), and "whore" (kaltak) to describe the protesters.[361]

Casualties

[edit]

As protests continued across Turkey, police use of tear gas and water cannons led to injuries running into thousands, including critical injuries, loss of sight, and a number of deaths. Over three thousand arrests were made.[1] Amnesty International claimed that police forces repeatedly used "unnecessary and abusive force to prevent and disperse peaceful demonstrations".[362] As a result, there were 11 fatalities.[67]

Media censorship and disinformation

[edit]Foreign media noted that, particularly in the early days (31 May – 2 June), the protests attracted relatively little mainstream media coverage in Turkey, due to either government pressure on media groups' business interests or simply ideological sympathy by media outlets.[5][363] The BBC noted that while some outlets are aligned with the AKP or are personally close to Erdoğan, "most mainstream media outlets – such as TV news channels HaberTurk and NTV, and the major centrist daily Milliyet – are loath to irritate the government because their owners' business interests at times rely on government support. All of these have tended to steer clear of covering the demonstrations."[363] Ulusal Kanal and Halk TV provided extensive live coverage from Gezi park.[364]

On 14 February 2014, released video footage revealed that there had in fact been no attack on a woman wearing a headscarf by protesters on 1 June.[365] The woman and Prime Minister Erdoğan had claimed in press conferences and political rallies that protesters had attacked her and her baby.[366]

International reaction

[edit]The AKP government's handling of the protests has been roundly criticised by other nations and international organisations, including the European Union,[367] the United Nations,[368] the United States,[30] the UK,[369] and Germany.[370]

Impact

[edit]Politics

[edit]According to Koray Çalışkan, a political scientist at Istanbul's Boğaziçi University, the protests are "a turning point for the AKP. Erdoğan is a very confident and a very authoritarian politician, and he doesn't listen to anyone anymore. But he needs to understand that Turkey is no kingdom, and that he cannot rule Istanbul from Ankara all by himself."[3] Çalışkan also suggested that the prospects for Erdoğan's plan to enact a new constitution based on a presidential system, with Erdoğan becoming the first President under this system, might have been damaged.[371]

Despite the AKP's support lying with religious conservatives, some conservative and Islamist organisations stood against Erdoğan. Groups such as the Anticapitalist Muslims and Revolutionist Muslims performed Friday prayers (salat) in front of the mescid çadırı (mosque tent) in Gezi Park on 7 and 14 June, one day before the police eviction.[372][373][374] Mustafa Akyol, a liberal Islamist journalist, described the events as the cumulative reaction of the people to Erdoğan.[375] Significant conservative opponents of the government include the religious writer İhsan Eliaçık, who accused Erdoğan of being a dictator,[376] Fatma Bostan Ünsal, one of the co-founders of the AKP, who expressed support to protests.[377] and Abdüllatif Şener, the former AKP Deputy Prime Minister, who strongly criticised the government in an interview with the left-wing Halk TV.[378]

Faruk Birtek, a sociology professor at Boğaziçi University, criticised the actions of Turkish police against protesters and likened them to the SS of Nazi Germany.[379] Daron Acemoglu, a professor of economics at M.I.T., wrote an op-ed for The New York Times about the protests, saying: "if the ballot box doesn't offer the right choices, democracy advances by direct action."[380]

The main cities where the protest took place answered "No" in 2017 Turkish constitutional referendum. In 2019 local elections candidates of the Nation Alliance, an opposition led coalition won most of these cities with Istanbul and Ankara switching to the main-opposition party CHP after 25 years.

A corruption case began against members of the PM cabinet and large construction company owners, including Ali Agaoglu, as his political affiliations may have enabled him to build in places otherwise not available for construction, like Gezi Park.[381]

Popular culture

[edit]The music group Duman composed and sang a song called "Eyvallah" referring to Erdoğan's words over admitting use of excessive force.[382]

The band Kardeş Türküler composed and sang a song called "Tencere Tava Havası" (Sound of Pots and Pans) referring to banging pots and pans in balconies in protest against Erdoğan.[383]

The Taiwanese Next Media Animation satirised Erdoğan over Gezi Protests with three humorous CGI-animated coverage series that included many symbols from the ongoing protests.[384][385][386] They also made an animation about Melih Gokcek, the mayor of Ankara, who accused Next Media Animation of controlling the protesters.[387] Those animations got reaction in the Turkish media as well.[388]

Boğaziçi Jazz Choir composed a song named "Çapulcu Musun Vay Vay", satirizing the word Chapulling and played it first in Istanbul subway and then in Gezi Park.[389]

Pop music singer Nazan Öncel produced a song "Güya" (Supposedly in Turkish) criticizing the government and Emek dispute, as "Nazan Öncel and Çapulcu Orchestra".[390]

Former Pink Floyd member Roger Waters, during his "The Wall Live" concert in Istanbul on 4 August 2013, expressed his support and offered condolences to the protesters in Turkish, projecting the pictures of the people killed during the protests in the background.[391][392]

The Colbert Report host Stephen Colbert had a segment on the protests creating the "autocratic anagram" Pro Gay Centipede Ray for Erdoğan and continued referring to him as "Prime Minister Centipede" multiple times which was criticised by some of the Turkish Media.[393]

Internationally known Turkish electropop musician Bedük composed, recorded and released a song named "It's A Riot" describing the protests and the fight for freedom in Turkey and released an official music video on 28 June, which has been created with all anonymous footages from different parts of Turkey, during the ongoing protests.[394]

Ozbi, a Turkish rapper (and member of the band Kaos), gained national fame by composing and recording a song named "Asi" (Rebel).[395]

World-famous alternative rock band Placebo included images representing Gezi protests in the music video for their latest song, "Rob the Bank".[396]

A Turkish rock band, The Ringo Jets, released a song called "Spring of War" about the protests.[397]

During their concert at Istanbul, Massive Attack named those who died in protests on the outdoor screen at their back with following sentences, "Their killers are still out there" and "We won't forget Soma".[398][399]

The Italian documentary Capulcu-Voices from Gezi focused on the protests.[400]

Tourism

[edit]In 2011, Turkey attracted more than 31.5 million foreign tourists,[401] ranking as the 6th most popular tourist destination in the world. Tourism has been described as "one of the most vital sources of income for Turkey",[402] raising concerns that "unrest would have a dire effect on Istanbul [...] and the larger tourism economy."[403][404] On 4 June, Hotel and Tourism investors from Istanbul reported that "more than 40 percent of hotel reservations" had been cancelled.[405]

- A spokesperson for the US State Department was reported to have noted that "the crackdown of the police forces armed with tear gas and water cannons happened in one of the most touristic places where many of the biggest hotels are located, indirectly warning that a travel advisory for U.S. citizens could be issued."[406] On 1 June 2013, the US Embassy in Turkey did indeed issue such a warning that "U.S. citizens traveling or residing in Turkey should be alert to the potential for violence."[407]

- The German Foreign Office issued a warning urging its citizens to avoid affected areas.[408]

Many world renowned and award-winning film-makers were in Istanbul for the 2013 Documentarist Film Festival, which had been postponed indefinitely due to the violent reaction of the Turkish authorities to peaceful protests there. The first two days of the festival, 1 and 2 June, did not occur due to the social upheaval and one of the main sites, Akbank Sanat, was unable to show films for an extended period of time due to its proximity to the protests. Petra Costa, the Brazilian director of the documentary film Elena, and Egyptian director of photography Muhammed Hamdy began filming the protests and reporting from the field.[citation needed]

2013 Mediterranean Games scandals

[edit]Since the beginning of the protests, demonstrations had taken place in Mersin, the city which was to host the 2013 Mediterranean Games. Since Erdoğan was due to speak at the opening ceremony of the games, there was speculation that protesters would take the opportunity to embarrass the government. Just 15 minutes after the tickets went on sale online they were all sold to an anonymous buyer and apparently distributed to various AKP organisations.[409][410] Combined with a boycott by local people of the games, this meant that the stadium was frequently nearly empty. Protesters were prevented from approaching the stadium by riot police, and were evicted from Mersin's Peace Park (Barış Parkı) the night before the games.[411] Tear gas, water cannons and rubber bullets were used against protesters.[412]

Other scandals which surrounded the games included: eight Turkish weight-lifters found to have performance-enhancing drugs in their blood and subsequently being disqualified[413] And a van belonging to the Games organisation transporting staff and athletes being seen in front of a brothel in Mersin.[414][415]

2020 Summer Olympics bid

[edit]Istanbul mayor Kadir Topbaş gave an interview expressing concern that the police's actions would jeopardise Istanbul's bid to host the 2020 Summer Olympics, saying "As Istanbul's mayor going through such an event, the fact that the whole world watched saddens me. How will we explain it? With what claims will we host the 2020 Olympic Games?"[416] As it turned out, "political unrest" was cited as one of the reasons for the failure of Istanbul's bid to host the Olympics, along with worries about the economy, the Syrian crisis and scandals surrounding the Mediterranean Games.[417]

Economy

[edit]On 3 June, Istanbul's stock exchange experienced a loss of 10.5% in a single day—the drop was "the biggest one-day loss in a decade."[418][419] The fall of BIST 100 index was the sharpest since August 2011,[420] and the yield on two-year lira bonds rose 71 basis points to 6.78 percent, the biggest jump since 2005. Turkish central bank had to auction out and buy Turkish Lira's in order to keep the exchange rate going. Next 11 funds have also dropped due to the Turkish prime minister's opposing views on freedom and democracy[421]

On 6 June, PM Erdoğan said the redevelopment plans would go ahead despite the protests.[312] Shortly after the comments were broadcast, the Turkish stock markets fell 5%.[422]

On 11 June, Rating's agency Moody's warned Turkey that ongoing protests would result in significant credit risks, leading "Istanbul's main share index" to fall an additional 1.7%.[423]

Temporary block of EU accession talks

[edit]On 25 June 2013 EU foreign ministers backed Germany's proposal to postpone further EU membership talks with Turkey for about four months due to the government's handling of the protests.[424] This delay raised new doubts about whether Turkey should ever be admitted to the European Union.[425] In early June, in comments on Turkey's possible membership, German Chancellor Angela Merkel did not address the compromise proposal but said Turkey must make progress on its relations with EU member Cyprus to give impetus to its membership ambitions.[426][427]

Anniversaries of Gezi Park protests

[edit]Police used tear gas and water cannons against demonstrators, and people were detained and/or injured, on 31 May 2014 in Istanbul, Ankara, and other cities.[428][429][430][431][432][433][434][435][436]

There have been demonstrations in Taksim in later anniversaries.

In the demonstrations in 2023, the press announcement included references to the 2023 earthquakes in Turkey, saying that the people having protected the Gezi Park 10 years ago is important because the Gezi Park is a place of gathering in cases of natural disaster.[437]

See also

[edit]

- Taksim Square massacre (1977)

- Environmental issues in Turkey

- Human rights in Turkey

- 2014 Turkish local elections

- 2014 Turkish presidential election

- Sendika.org

- DİSK

- TMMOB

Notes

[edit]- ^ According to a survey by GENAR, 74.6% of Gezi Park protesters who voted for a party in the previous elections voted for CHP. "Geziciler ile ilgili en kapsamlı anket" (in Turkish). T24. 13 June 2013. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Gezi Park Protests: Brutal Denial of the Rıght To Peaceful Assembly in Turkey". Amnesty International. 2 October 2013.

- ^ Holly Williams (1 June 2013). "Massive, violent crowds protest Turkish leader's policies". CBS News. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ^ a b c "Turkey protests spread from Istanbul to Ankara". Euronews. 31 May 2013. Archived from the original on 30 April 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ^ "Turkey: Istanbul clashes rage as violence spreads to Ankara". The Guardian. London. 31 May 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Letsch, Constanze (31 May 2013). "Turkey protests spread after violence in Istanbul over park demolition". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Protesters are young, libertarian and furious at Turkish PM, says survey". 5 June 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ "Gezi Park Protests: Brutal Denial of the Tight To Peaceful Assembly in Turkey" (PDF). Amnesty International. 12 October 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ "'Gezi Parkı eylemlerinde orantısız güç kullanıldı' - Genel Bakış- ntvmsnbc.com". ntvmsnbc.com.

- ^ "Polisin orantısız gücüne bir tepki de Karşıyaka Platformu'ndan geldi". Malatya Gerçeği. Archived from the original on 12 March 2014.

- ^ Efe Can Gürcan; Efe Peker, " Challenging Neoliberalism at Turkey's Gezi Park" p83. Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- ^ A.Z. (2 June 2013). "Turkish politics: Resentment against Erdogan explodes". Economist.com. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ "- How to predict a revolution using the center-periphery dissonance factor". Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ^ a b The Daily Dot, 4 June 2013, Refusing oppression, Turkish protesters release a list of demands

- ^ "Anakara'da Gerginlik, CHP'den YSK'Ya Seçim Sonucu 'Hile Protestosu'". avrupagazete.com. 1 April 2014. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ "Mahkeme, Gezi Parkı'nda yürütmeyi durdurdu". zaman.com.tr. Archived from the original on 26 November 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Beyoğlu Belediye Başkanı: Gezi Parkı eylemleri geride kaldı (Turkish)/Mayor of Beyoğlu: Gezi Park Protests in the past". Hürriyet. 23 August 2013. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ "Turkey-EU relations exponentially decelerated especialy [sic] after Gezi Park protests". eurodialogue.eu. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Turkish Foreign Policy after Gezi Park Protests". academia.edu. Retrieved 3 May 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Turkey: Gezi Park protests on year on - police remain unpunished, demonstrators go on trial". amnesty.org.uk. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "The Last Chance to Stop Turkey's Harsh New Internet Law". pulitzercenter.org. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Explained: Turkey's controversial security bill". Hürriyet Daily News. 22 February 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "bbc.com". BBC News. 29 April 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Who are the protestors?". 2 June 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ^ "Ülkücüler Taksim'e çıktı". February 2020.

- ^ "Gezi Parkı'nda öfke kardeşliği". Aksiyon. 10 June 2013. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

- ^ "GEZİ PARKI İŞGALİ VE ANARŞİSTLERİN BİLDİRİSİ". itaatsiz dergi. Archived from the original on 5 November 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ "Feminists join protests in Turkey as they call for equality". Reuters. 5 June 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ "Artı Bir Tv'de Gezi Parkı'nı Konuştuk". Archived from the original on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ^ "Gays in the park". Vocativ. 14 June 2013. Archived from the original on 14 June 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ a b "Turkey police clash with Istanbul Gezi Park protesters". BBC News. 1 June 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ^ sosyalistcerkesler (June 2013). "Sosyalist Çerkesler de Direnişte! – Sosyalist Çerkesler" (in Turkish). Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ^ "Sosyalist Çerkesler, Gezi Parkı direnişi için Kadıköy'de". Sosyalist Çerkesler. 3 June 2013.

- ^ a b Kotsev, Victor (2 June 2013). "How the Protests Will Impact Turkey at Home and Abroad". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ^ "Libertarians in Turkey support protests". Students For Liberty. 11 June 2013. Archived from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ a b c "Supporter groups of Istanbul's three major teams join forces for Gezi Park". Hürriyet Daily News. 1 June 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ^ "Why the 3H Sides with the Gezi Park Protests?". 3H Movement. 5 June 2013. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Turkey unrest: Unions call strike over crackdown". BBC News. 17 June 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ^ "İstanbul Barosu vatandaşlara gönüllü olarak avukatlık yapacak". Milliyet. 31 May 2013. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ "DİSK, KESK, TMMOB, TTB, TDB iş bıraktı". CNN Türk. 17 June 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ "Gazeteci Örgütlerinden Polis Şiddetine Protesto - bianet". Bianet - Bagimsiz Iletisim Agi.

- ^ "WWF stands up for Taksim Gezi Park". Tugba Ugur.

- ^ "Anonymous #OpTurkey'i başlattı | Mynet Haber". 10 June 2013. Archived from the original on 10 June 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ^ "RedHack's latest victim is Union of Municipalities of Turkey, login credentials leaked". Hacker News Bulletin. 23 August 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ^ "RedHack released documents with the name of police officers who killed Turkish Protester 'Abdullah'". Hacker News Bulletin. 11 September 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ^ "28 mayıs 2013 taksim gezi parkı direnişi". ekşi sözlük (in Turkish). Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ "31 mayis taksim gezi parki direnisi". www.incisozluk.com.tr. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ "Intervention in Taksim will carry on until full security is ensured: Istanbul governor". hurriyetdailynews. 11 June 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ^ "Gezi'ye rekor katılım: 7.5 milyon yurttaş". Aydinlik. 13 September 2013. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ "Türkiye İnsan Hakları Vakfı: 'Gezi Parkı gözaltı sayısı 3 bin 773, tutuklu sayısı 125'". Dag Medya. 2 August 2013. Archived from the original on 5 August 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ^ "2.5 million people attended Gezi protests across Turkey: Interior Ministry". Hürriyet Daily News. 23 June 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ "2.5 milyon insan 79 ilde sokağa indi". Milliyet. 23 June 2013. Archived from the original on 24 June 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ^ "A Graphic History of the Gezi Resistance". Bianet. 10 June 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ "Gül understands it while Erdoğan doesn't". Radikal. 4 June 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ^ "Devrimci Müslümanlar'da "marjinal" oldu! - Aktif en az 3,545,000 kişi". Yurt. 20 September 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2013.