2019–20 Australian bushfire season

| 2019–20 Australian bushfire season | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top left: Sydney's George Street blanketed by smoke in December 2019; Orroral Valley fire seen from Tuggeranong; damaged road sign along Bells Line of Road; Gospers Mountain bushfire; smoke plume viewed from the International Space Station; uncontained bushfire in South West Sydney | |

| Date(s) | June 2019 – May 2020 |

| Location | Australia |

| Statistics | |

| Burned area | Approximately 243,000 km2 (60,000,000 acres)[1] |

| Impacts | |

| Deaths | |

| Structures destroyed | 9,352 |

| Damage | US$69–159 billion |

| Ignition | |

| Cause | Fire ignitions

Enhanced fires

|

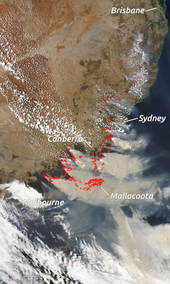

The 2019–20 Australian bushfire season,[a] or Black Summer, was one of the most intense and catastrophic fire seasons on record in Australia. It included a period of bushfires in many parts of Australia, which, due to its unusual intensity, size, duration, and uncontrollable dimension, was considered a megafire by media at the time.[16][b] Exceptionally dry conditions, a lack of soil moisture, and early fires in Central Queensland led to an early start to the bushfire season, beginning in June 2019.[18] Hundreds of fires burnt, mainly in the southeast of the country, until May 2020. The most severe fires peaked from December 2019 to January 2020.

The fires burnt an estimated 24.3 million hectares (243,000 square kilometres),[c][1] destroyed over 3,000 buildings (including 2779 homes),[19] and killed at least 34 people.[20][21][22][23][24][d] According to the University of Tasmania’s Menzies Institute, bushfire smoke was responsible for more than 400 deaths, reported by the Medical Journal of Australia.[25]

In December 2023 the Sydney Morning Herald reported a large volume of smoke in the Sydney basin resulted from the so called Gospers Mountain "megablaze" after the NSW Rural Fire Service lost control of back burning in November and December 2019.[26] It was claimed that three billion terrestrial vertebrates – the vast majority being reptiles – were affected and some endangered species were believed to be driven to extinction.[27] The cost of dealing with the bushfires was expected to exceed the A$4.4 billion of the 2009 Black Saturday fires,[28] and tourism sector revenues fell by more than A$1 billion (US$690 million).[29] Economists estimated the bushfires may have cost A$100–230 billion (US$69–159 billion) in economic losses,[e] which became the costliest natural disaster in Australian history.[30] Nearly 80% of Australians were affected by the bushfires in some way.[31] At its peak, air quality dropped to hazardous levels in all southern and eastern states,[32] and smoke had been moving upwards of 11,000 kilometres (6,800 mi) across the South Pacific Ocean, impacting weather conditions in other continents.[33][34] Satellite data estimated the carbon emissions from the fires to be around 715 million tons,[35][36] surpassing Australia's normal annual bushfire and fossil fuel emissions by around 80%.[37][38][39]

From September 2019 to March 2020, fires heavily impacted various regions of the state of New South Wales (NSW). In eastern and north-eastern Victoria, large areas of forest burnt out of control for four weeks before the fires emerged from the forests in late December. Multiple states of emergency were declared across NSW,[40][41][42] Victoria,[43] and the Australian Capital Territory.[44] Reinforcements from all over Australia were called in to assist fighting the fires and relieve exhausted local crews in NSW. The Australian Defence Force was mobilised to provide air support to the firefighting effort and to provide manpower and logistical support.[45][46] Firefighters, supplies and equipment from Canada, New Zealand, Singapore and the United States, among others, helped fight the fires.[47] An air tanker[48] and two helicopters[49][2] crashed during operations, killing three crew members. Two fire trucks were caught in fatal accidents, killing three firefighters.[50][51]

By 4 March 2020, all fires in NSW had been extinguished completely (to the point where there were no fires in the state for the first time since July 2019),[52] and the Victoria fires had all been contained.[53] The last fire of the season occurred in Lake Clifton, Western Australia, in early May.[54]

There has been considerable debate regarding the underlying cause of the intensity and scale of the fires, including the role of fire management practices and climate change, which during the peak of the crisis attracted significant international attention,[55] despite previous Australian fires burning much larger areas (1974–75) or killing more people (2008–09).[56] Politicians visiting fire impacted areas received mixed responses, in particular Prime Minister Scott Morrison.[57][58] An estimated A$500 million (US$345 million) was donated by the public at large, international organisations, public figures and celebrities for victim relief and wildlife recovery. Convoys of donated food, clothing and livestock feed were sent to affected areas.

Overview

[edit]Starting from late July early September 2019, fires heavily impacted various regions of the state of New South Wales, such as the North Coast, Mid North Coast, the Hunter Region, the Hawkesbury and the Wollondilly in Sydney's far west, the Blue Mountains, Illawarra and the South Coast, Riverina and Snowy Mountains with more than 100 fires burnt across the state. In eastern and north-eastern Victoria, large areas of forest burnt out of control for four weeks before the fires emerged from the forests in late December, taking lives, threatening many towns and isolating Corryong and Mallacoota. A state of disaster was declared for East Gippsland.[59] Significant fires occurred in the Adelaide Hills and Kangaroo Island in South Australia and parts of the ACT. Moderately affected areas were south-eastern Queensland and areas of south-western Western Australia, with a few areas in Tasmania being mildly impacted.

On 12 November 2019 catastrophic fire danger was declared in the Greater Sydney region for the first time since the introduction of this level in 2009 and a total fire ban was in place for seven regions of New South Wales, including Greater Sydney.[60] The Illawarra and Greater Hunter areas also experienced catastrophic fire dangers, and so did other parts of the state, including the already fire ravaged parts of northern New South Wales.[61] The political ramifications of the fire season have been significant. A decision by the New South Wales Government to cut funding to fire services based on budget estimates, as well as a holiday taken by Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison, during a period in which two volunteer firefighters died, and his perceived apathy towards the situation, resulted in controversy.

As of 14 January 2020[update], 18.626 million hectares (46.03 million acres) had burnt or was burning across all Australian states and territories.[62] Ecologists from The University of Sydney estimated 480 million mammals, birds, and reptiles were lost since September with concerns that entire species of plants and animals may have been wiped out by bushfire,[63][64] later expanded to more than a billion.[65]

In February 2020 it was reported that researchers from Charles Sturt University found that the deaths of nine smoky mice were from "severe lung disease" caused by smoke haze that contained PM2.5 particles coming from bushfires 50 kilometres away.[66]

By the time the fires had been extinguished there, they destroyed 2,448 homes, as well as 284 facilities and more than 5,000 outbuildings in New South Wales alone.[67] Twenty-six people were confirmed to have been killed in New South Wales since October.[67] The last fatality reported was on 23 January 2020 following the death of a man near Moruya.[48]

In New South Wales, the fires burnt through more land than any other blazes in the past 25 years, in addition to being the state's worst bushfire season on record.[68][69][70] NSW also experienced the longest continuously burning bushfire complex in Australia's history, having burnt more than 4 million hectares (9,900,000 acres), with 70-metre-high (230 ft) flames being reported.[71] In comparison, the 2018 California wildfires consumed 800,000 hectares (2,000,000 acres) and the 2019 Amazon rainforest wildfires burnt 900,000 hectares (2,200,000 acres) of land.[72]

Whereas these bushfires are regarded by the NSW Rural Fire Service as the worst bushfire season in memory for that state,[73] the 1974–75 bushfires were nationally much larger[d] consuming 117 million hectares (290 million acres; 1,170,000 square kilometres; 450,000 square miles).[74] However, due to their lower intensity and remote location, the 1974 fires caused around A$5 million (approximately A$36.5 million in 2020[75]) in damage.[74] In December 2019 the New South Wales Government declared a state of emergency after record-breaking temperatures and prolonged drought exacerbated the bushfires.[76][77]

Due to safety concerns and significant public pressure, New Year's Eve fireworks displays were cancelled across New South Wales including highly popular events at Campbelltown, Liverpool, Parramatta, and across Sydney's Northern Beaches, and as well in the nation's capital of Canberra.[78][79] As temperatures reached 49 °C (120 °F), the New South Wales Premier Gladys Berejiklian called a fresh seven-day state of emergency with effect from 9 am on 3 January 2020.[80][81][82]

On 23 January 2020, a Lockheed C-130 Hercules air tanker (N134CG) crashed at Peak View near Cooma while waterbombing a blaze. The aircraft was destroyed, resulting in the death of the three American crew members on board.[48][83] It was one of eleven large air tankers brought to Australia for the fire season from Canada and US.[84] Reaching the crash site proved difficult due to the active bushfires in the area.[85] The crash was located in dense bushland, and spanned approximately 1 kilometre (0.62 mi).[86] An investigation was begun by the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) to determine the cause of the accident.[85]

A preliminary ATSB report was released on 28 February. One fact determined was that the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) was faulty and " … had not recorded any audio from the accident flight." As of December 2020[update] the investigation had not been completed.[87]

On 31 January 2020, the Australian Capital Territory declared a state of emergency in areas around Canberra[88] as several bushfires threatened the city, having burnt 60,000 hectares (150,000 acres).[89]

On 7 February 2020, it was reported that torrential rain across most of south-east Australia had extinguished a third of extant fires;[90] with only a small number of uncontrolled fires remaining by 10 February.[91]

| State / territory | Fatalities | Homes lost | Area (estimated) | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ha | acres | ||||

| Northern Territory | 0 | 5 | 6,800,000 | 16,800,000 | Area, includes mainly scrub fires, which are within the normal range of area burnt by bushfires each year;[62] homes[92] |

| New South Wales | 26 | 2,448 | 5,500,000 | 13,600,000 | Area;[67] fatalities;[67] homes[67] |

| Queensland | 0 | 48 | 2,500,000 | 6,180,000 | Area, includes scrub fires;[62] homes[92][f] |

| Western Australia | 0 | 1 | 2,200,000 | 5,440,000 | Area, includes scrub fires;[62] homes[92] |

| Victoria | 5 | 396 | 1,500,000 | 3,710,000 | Area;[62] fatalities;[21] homes[97] |

| South Australia | 3 | 151 | 490,000 | 1,210,000 | Area;[62] fatalities;[98] homes (KI:65)[99] (AH:86)[100] |

| Australian Capital Territory | 0 | 0 | 86,464 | 213,660 | Area[101] |

| Tasmania | 0 | 2 | 36,000 | 89,000 | Area;[62] homes[92] |

| Total | 34 | 3,500+ | 18,736,070 | 46,300,000 | [g][d][105][106] Total area estimate from 13 February 2020 |

Fire potential

[edit]The Garnaut Climate Change Review of 2008 stated:[107][108]

Recent projections of fire weather (Lucas, et al., 2007)[14] suggest that fire seasons will start earlier, end slightly later, and generally be more intense. This effect increases over time, but should be directly observable by 2020.

To describe emerging fire trends the study by Lucas and others defined two new fire weather categories, "very extreme" and "catastrophic".

The analysis by the Bushfire CRC, the Australian Bureau of Meteorology, and CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research found that the number of "very high" fire danger days generally increases 2–13% by 2020 for the low scenarios (global increase by 0.4 °C (0.72 °F)) and 10–30% for the high scenarios (global increase by 1.0 °C (1.8 °F)). The number of "extreme" fire danger days generally increases 5–25% by 2020 for the low scenarios and 15–65% for the high scenarios.[14]

In April 2019 a group of former Australian fire services chiefs, Emergency Leaders for Climate Action, warned that Australia was not prepared for the upcoming fire season. They called on the next prime minister[h] to meet the former emergency service leaders "who will outline, unconstrained by their former employers, how climate change risks are rapidly escalating".[109][110] Greg Mullins, the second-longest serving fire and rescue commissioner in New South Wales and now a councillor with the Climate Council, said he thought the coming summer was going to be "the worst I have ever seen" for fire crews, and renewed his calls for the government to take urgent action to address climate change and stop Australia's rising emissions.[110]

In August 2019 the federally funded Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC published a seasonal outlook report which advised of "above normal fire potential" for southern and southeast Queensland, the east coast areas of New South Wales and Victoria, for parts of Western Australia and South Australia.[111][112] In December 2019, the Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC updated their advice of "above normal fire potential".[113]

Regions affected

[edit]The Australian National University reported that the area burned in 2019–2020 was "well below average" due to low fuel levels and fire activity in unpopulated parts of Northern Australia, but that "despite low fire activity overall, vast forest fires occurred in southeast Australia from southeast Queensland to Kangaroo Island."[17]

New South Wales

[edit]

The NSW statutory Bush Fire Danger Period normally begins on 1 October and continues through until 31 March.[114] In 2019–20, the fire season started early with drought affecting 95 percent of the state and persistent dry and warm conditions across the state.[115] Twelve local government areas started the Bush Fire Danger Period two months early, on 1 August 2019,[116] and nine more started on 17 August 2019.[115][117] In the week preceding 10 February 2020, a wide band of heavy rain swept through most of coastal New South Wales, extinguishing a significant number of fires; it left 33 active fires, of which five were uncontrolled, all located in the Bega Valley and Snowy Mountains regions.[91][118] Between July 2019 and 13 February 2020, the NSW Rural Fire Service reported that 11,264 bush or grass fires burnt 5.4 million hectares (13 million acres), destroyed 2,439 homes, and approximately 24 megalitres (5.3 million imperial gallons; 6.3 million US gallons) of fire retardant was used.[119]

North Coast

[edit]On 6 September 2019, the northern parts of the state experienced extreme fire dangers. Fires included the Long Gully Road fire near Drake which burnt until the end of October, killing two people and destroying 43 homes;[120] the Mount McKenzie Road fire which burnt across the southern outskirts of Tenterfield, and severely injured one person, destroyed one home and badly damaged four homes; and the Bees Nest fire near Ebor which burnt until 12 November and destroyed seven homes.[121]

A major fire began in Chaelundi State Forest, west of Nymbodia, Fire spread south west of Grafton during an intense growth period of the fire where it became a PyroCumulonimbus[122] and over ran the village of Nymboida, destroying 80 houses.[123] Smaller fires in the area include the Myall Creek Road fire.[91]

Mid North Coast

[edit]In the Port Macquarie-Hastings area, the first fire was reported at Lindfield Park on 18 July 2019,[124] burning in dry peat swamp and threatened homes at Sovereign Hills and crossed the Pacific Highway at Sancrox. On 12 February 2020, the fire was declared extinguished after 210 days, having burnt 858 hectares (2,120 acres), of which approximately 400 hectares (990 acres) was underground;[125][126] near the Port Macquarie Airport.[127] The peat fire was extinguished after 65 megalitres (14 million imperial gallons; 17 million US gallons) of reclaimed water were pumped into adjacent wetlands; followed by 260 millimetres (10 in) of rain over five days.[125] In the Port Macquarie suburb of Crestwood a fire started on 26 October from a dry electrical storm. Water bombers were delayed the following day in attempts to bring the fire burning in swampland to the south west of Port Macquarie under control. A back burn on 28 October got away from New South Wales Rural Fire Service (NSWRFS) volunteers after a sudden wind change pushing the fire south towards Lake Cathie and west over Lake Innes. Port Macquarie and surrounding areas were blanketed in thick smoke on 29 October with ongoing fire activity over the following week caused the sky to have an orange glow.

A fire burnt in wilderness areas on the Carrai Plateau west of Kempsey. This fire joined up with the Stockyard Creek fire and together with the Coombes Gap fire and swept east towards Willawarrin, Temagog, Birdwood, Yarras, Bellangary, Kindee and Upper Rollands Plains. Land around Nowendoc and Yarrowich was also burnt. As of 6 December 2019[update], this fire burnt nearly 400,000 hectares (988,422 acres),[128][129][130] destroying numerous homes and claiming the lives of three people.[131]

North-west of Harrington near the Cattai Wetlands a fire started on 28 October, this fire threatened the towns of Harrington, Crowdy Head and Johns River as it burnt north towards Dunbogan. This fire claimed one life at Johns River,[131] where it also destroyed homes, and burnt more than 12,000 hectares (29,653 acres).[citation needed]

At Hillville, a fire grew large due to hot and windy conditions, resulting in disorder in the nearby town of Taree, to the north. Buses were called in early to take students home before the fire threat became too dangerous. On 9 November 2019, the fire reached Old Bar and Wallabi Point, threatening many properties. The following two days saw the fire reach Tinonee and Taree South, threatening the Taree Service Centre. Water bombers dropped water on the facility to protect it. The fire briefly turned in the direction of Nabiac before wind pushed it towards Failford. Other communities affected included Rainbow Flat, Khappinghat, Kooringhat and Purfleet. A spot fire jumped into Ericsson Lane, threatening businesses. It ultimately burnt 31,268 hectares (77,260 acres).[132][133]

At Dingo Tops National Park a small fire that started in the vicinity of Rumba Dump Fire Trail burned down the ranges and impacted the small communities of Caparra and Bobin. Fanned by near catastrophic conditions, the fire grew considerably on 8 November 2019 and consumed nearly everything in its path. The small community of Caparra lost fourteen homes in a few hours as the bushfire continued towards the small village of Bobin, where numerous homes and the Bobin Public School were destroyed in the fire.[134] Fourteen homes were lost on one street in Bobin. The NSWRFS sent out alerts to people in Killabakh, Upper Lansdowne, Kippaxs, Elands, and Marlee to monitor conditions.[citation needed]

2019 Rally Australia, planned to be the final round of the 2019 World Rally Championship, was a motor racing event scheduled to be held in Coffs Harbour across 14–17 November.[135] A week before the rally was due to begin, the bushfire began to affect the region surrounding Coffs Harbour, with event organisers shortening the event in response to the deteriorating conditions.[136] With the situation worsening, repeated calls from competitors (most of which were European-based) to cancel the event prevailed with the event cancelled on 12 November.[137][138]

In late December 2019, fires started on both sides of the Pacific Highway around the Coopernook region. They burnt 278 hectares (687 acres) before they were brought under control.[citation needed]

Hunter

[edit]

In the Hunter region, the Kerry Ridge fire burnt in the Wollemi National Park, Nullo Mountain, Coricudgy and Putty state forests in the Mid-Western Region, Muswellbrook and Singleton local government areas.[139] The fire was extinguished on 10 February 2020,[91] having burnt approximately 191,000 hectares (471,971 acres) over 79 days.[140]

Blue Mountains and Hawkesbury

[edit]

The Gospers Mountain Fire was ignited by lightning on 26 October near Gospers Mountain in the Wollemi National Park. Over the following 16 days the fire burnt an estimated 56,000 ha (140,000 acres) and was largely managed by the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. On 11 November the NSW Rural Fire Service took control of fire management and issued a pre-emptive Section 44 declaration ahead of anticipated deteriorating conditions.

Around 11 November 2019, the NSW Rural Fire Service devised a strategy to contain the Gospers Mountain Fire using primary roads, major fire trails and an over-reliance on large-scale strategic backburning.[141] This strategy was calculated to result in an area burnt of 450,000 ha.[142] Under this strategy eight strategic backburns were carried out by the NSW Rural Fire Service, generally many kilometres from the edge of the Gospers Mountain Fire, with each backburn failing and escaping containment. This caused the fire to significantly increase in size. In each instance the NSW Rural Fire Service described the escaped backburns as the "Gospers Mountain Fire", even though in many cases, the backburns were ignited separately. The area burnt by these escaped backburns accounted for over 130,000 hectares - nearly a quarter of the total size of the Gospers Mountain Fire.[141]

Escaped Backburns

[edit]- On 15 November, at Putty Road, Wallaby Swamp Trail and Staircase Spur Trail at Colo Heights

- On 19 November, at Putty Road, Barina Road and Wheelbarrow Ridge Road at Colo Heights

- On 4 December, at Cerones Track, Colo Heights

- On 5 December, at Upper Colo Road, Colo Heights

- On 5–6 December at Mountain Lagoon, between Colo Heights and Bilpin

- On 7 December, at Glowworm Tunnel Road on the Newnes Plateau

- On 12 December, at Blackfellows Hands Trail at Newnes Plateau

- On 14 December at Mt Wilson Road (Mt Wilson Backburn)

Mt Wilson Backburn

[edit]At 10am on 14 December the NSW Rural Fire Service commenced a large backburn in the Mount Wilson area. Due to poor fire weather conditions and heavy fuel loads, the backburn quickly grew out of control, threatening houses in Mount Wilson. The escaped backburn spread east of Mount Wilson Road and on 15 December, under deteriorating conditions, impacted Mount Tomah, Berambing and Bilpin. Due to confusion around the source of the fire and inaccurate warnings, many impacted residents were unaware that the escaped backburn posed a threat to their properties.[143][144] The fire destroyed numerous houses and buildings, and then jumped the Bells Line of Road into the Grose Valley.[145]

On 19 December 2019 the fire caused by the escaped RFS Mt Wilson backburn crossed south of the Grose River. This section of the fire was then annexed by the NSW Rural Fire Service, which declared a new fire called the Grose Valley Fire.[146] On 21 December, a catastrophic day, the escaped RFS Backburn impacted Mount Victoria, Blackheath, Bell, Clarence, Dargan and Bilpin, resulting in the destruction of dozens of homes. Homes were also lost in Lithgow due to previously escaped Glow Worm Tunnel and Blackfellows Hands Trail backburns.

The NSW Rural Fire Service reported the Gospers Mountain Fire as contained on 12 January 2020, stating that the fire was caused by a lightning strike on 26 October.[147] On 4 February 2020 the escaped Mt Wilson Backburn was declared out.[148] The amount of area burnt by the original Gospers Mountain Wildfire remains contested, as a significant portion of the fire was caused by multiple, separate backburns which increased the fire area. On 10 February 2020, NSW Rural Fire Service announced a torrential rain event over the preceding week had extinguished the Gospers Mountain fire.[91][149]

Smaller fires in the area include the Erskine Creek fire.[91] Additional fires in Balmoral, at the south eastern extent of the Blue Mountains, were also caused by NSW Rural Fire Service backburning.[150]

The Gospers Mountain fire was widely reported as the largest forest fire ever recorded in Australia, burning more than 500,000 hectares. A significant amount of the final burnt area was a result of escaped backburning operations by the NSW Rural Fire Service. 81% of the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area burned.[31]

Sydney

[edit]

On 12 November 2019, under Sydney's first ever catastrophic fire conditions, a fire broke out in the Lane Cove National Park south of Turramurra. Under strong winds and extreme heat the fire spread rapidly, growing out of control and impacting the suburban interface across South Turramurra. One house caught alight in Lyon Avenue, but was saved by quick responding firefighters. As further crews arrived and worked to protect properties, a C-130 Air Tanker made several fire retardant drops directly over firefighters and houses, saving the rest of the suburb. The fire was ultimately brought under control several hours later, with one firefighter injured suffering a broken arm.[151][152][153]

Because of the bushfires occurring in the surrounding regions, the Sydney metropolitan area suffered from dangerous smoky haze for several days throughout December, with the air quality being eleven times the hazardous level on some days,[154][155] making it even worse than New Delhi's,[156] where it was also compared to "smoking 32 cigarettes" by Associate Professor Brian Oliver, a respiratory diseases scientist at the University of Technology Sydney.[157]

On 10 December 2019 the fire impacted the south-western Sydney suburbs of Nattai and Oakdale, followed by Orangeville and Werombi, threatening hundreds of houses and resulting in the destruction of one building. The fire continued to flare up sporadically, coming out of the dense bush and threatening properties in Oakdale and Buxton on 14 and 15 December.[citation needed] The fire moved south-east towards the populated areas of the Southern Highlands and impacted the townships of Balmoral, Buxton, Bargo, Couridjah and Tahmoor in far south-western Sydney. Substantial property losses occurred across these areas, in particular multiple fire trucks were overrun by fire, with several firefighters taken to hospital and two airlifted in critical condition. Later that night, two firefighters were killed when a tree fell onto the road and their tanker rolled, injuring three other crew members. The situation deteriorated on 21 December when the fire changed direction and attacked Balmoral and Buxton once more from the opposite side, with major property losses in both areas.[158] On New Year's Eve there were fears of this fire impacting the towns of Mittagong, Braemar, and surrounding areas.

On 31 December 2019, a grass fire broke out in the sloped woodlands of Prospect Hill, in Western Sydney, where it headed north towards Pemulwuy along the Prospect Highway. The fire impacted a large industrial area and threatened numerous properties before being brought under control by 9:30 pm. Approximately 10 hectares (25 acres) and a number of historic Monterey pine trees were burnt.[159]

The Sydney City fireworks display was allowed to continue with a special exemption from fire authorities, despite protests.[160] Despite warnings from authorities, numerous fires were sparked across Sydney as a result of illegal fireworks, including a blaze which threatened properties at Cecil Hills in Sydney's south west.[161]

On 4 January 2020, Sydney's western suburb Penrith recorded its hottest day on record at 48.9 °C (120.0 °F) making it the hottest place on Earth at the time.[162][163]

On 5 January 2020, a fire broke out in bushland at Voyager Point in Sydney's south-west, spreading rapidly under a strong southerly wind and impacting numerous houses in Voyager Point and Hammondville.[164] As the fire moved north, authorities closed the M5 Motorway due to smoke conditions and prepared for the fire to impact the New Brighton housing estate. Firefighters on the ground assisted by numerous waterbombing aircraft held the fire south of the motorway and prevented any property losses, containing the fire to 60 hectares (150 acres).[165]

Southern Highlands

[edit]In late October 2019, a number of fires started in remote bushland near Lake Burragorang in the Kanangra-Boyd National Park south-west of Sydney. Due to the extreme isolation of the area and rugged inaccessible terrain, firefighters struggled to contain the fires as they began to spread through the dense bushland. These multiple fires ultimately all merged to become the Green Wattle Creek fire. The fire continued to grow in size and intensity, burning towards the township of Yerranderie. Firefighters undertook backburning around the town whilst helicopters and fixed wing aircraft worked to control the spread of the fire. The fire passed Yerranderie but continued to burn through the national park towards south-western Sydney. On 5 December under severe weather conditions, the fire jumped the Lake Burragorang and began burning towards populated areas within the Wollondilly area.

On 19 December 2019, the fire continued east towards the Hume Highway (resulting in its closure for several hours), impacting the township of Yanderra. Over the following days as the fire continued to progress to the south east, both Yerrinbool and Hill Top were threatened by the fire.[166]

As well as expanding to the south and east, the fire also spread in a westerly direction, headed towards Oberon. The Oberon Correctional Centre was evacuated in anticipation of the advancing fire impact along its western flank.[167] On 2 January, the fire hit the popular and historic Jenolan Caves area, destroying multiple buildings including the local fire station. The centrepiece of the precinct, Jenolan Caves House, was saved.[168] On 10 February 2020, NSW Rural Fire Service announced a torrential rain event over the preceding week had extinguished the Green Wattle Creek fire.[91]

South Coast

[edit]

On 30 December 2019 weather conditions drastically deteriorated across the south-eastern areas of the state, with major fires breaking out and escalating in the Dampier State Forest, Deua River Valley, Badja, Bemboka, Wyndham, Talmalolma and Ellerslie, hampering firefighters already stretched by the Currowan, Palerang and Clyde Mountain fires.[169] As temperatures were forecast to reach 41 °C (106 °F) on the South Coast, Premier Berejiklian declared a seven-day state of emergency on 2 January 2020 with effect from 9 am on the following day, including an unprecedented[170] 14,000-square-kilometre (5,400 sq mi) "tourist leave zone" from Nowra to the edge of Victoria's northern border.[80][81][82]

A blaze on the South Coast started off at Currowan and travelled up to the coastline after jumping across the Princes Highway, threatening properties around Termeil. Residents in Bawley Point,[171] Kioloa, Depot Beach, Pebbly Beach, Durras North and Pretty Beach were told to either evacuate to Batemans Bay or Ulladulla or stay to protect their property. One home was lost.[citation needed] As of 2 January 2020[update], the Currowan fire was burning between Batemans Bay in the south, Nowra in the north, and east of Braidwood in the west. The fire had burnt more than 258,000 hectares (640,000 acres) and was out of control. The Currowan fire had merged with the Tianjara fire in the Morton National Park to the south west of Nowra; and the Charleys Forest fire had grown along the fire's western flank; and on the fire's southern flank, the fire had merged with the Clyde Mountain fire.[172]

By 26 December 2019, the Clyde Mountain fire was burning on the southern side of the Kings Highway, into the Buckenbowra and Runnyford areas. Around 4 am on 31 December, the fire had crossed the Princes Highway near Mogo, and the highway was closed between Batemans Bay and Moruya.[173] Around 7 am on 31 December, the fire impacted the southern side of Batemans Bay, causing the loss of around ten businesses and damage to many others. The fire also crossed the Princes Highway in the vicinity of Round Hill and impacted the residential suburbs of Catalina, as well as beach suburbs from Sunshine Bay to Broulee. Residents and holiday makers were forced to flee to the beaches.[80] On 23 January this fire escalated back to emergency level as the blaze roared towards the coastal town of Moruya, a town largely unaffected by bushfires in recent weeks.

At nearby Conjola Park, numerous homes were lost as the embers jumped across Conjola Lake, landing in gutters and lighting up houses. On one street there were only four houses still standing. As of 2 January 2020[update], at least two people died and a woman was missing.[174] Isolated hamlets of Bendalong and Manyana and Cunjurong Point were additionally ablaze, with holiday-makers evacuated on 3 January 2020. As of 6 January 2020[update], all are still without power.[175]

As of 5 January 2020[update], in the Bega Valley Shire, the Border fire that started in north-eastern Victoria was burning north into New South Wales towards the major town of Eden, and had impacted the settlements of Wonboyn and surrounding areas including Kiah, Lower Towamba and parts of Boydtown. Part of the fire was burning in inaccessible country and continued to head in a north-westerly direction towards Bombala as well as northerly to just south of Nethercote. The fire had burnt more than 60,000 hectares (150,000 acres) and was out of control.[176][177] On 2 February 2020 in the Bega Valley, the 177,000-hectare (437,377-acre) Border fire pushed north, while three other bushfires in the south-west had merged into one. Kristy McBain, the Bega Valley shire council mayor, said more than 400 properties and homes had been lost after 34 days of fire activity in the area.[178]

On 9 February 2020, NSW Rural Fire Service announced a torrential rain event over the preceding week had extinguished both the Morton and Currowan fires,[91] with the latter having burnt 499,621 hectares (1,234,590 acres) over 74 days and destroying 312 homes.[179]

Riverina

[edit]On 30 December 2019, the Green Valley fire burning east of Albury near Talmalmo (which had started the day prior) developed into an unprecedented fire event for the Snowy Valleys[180] as a result of extreme local conditions. The smoke plume rose to an estimated 8,000 metres (26,000 ft) and developed a pyro-cumulonimbus cloud, becoming a firestorm. The result was extreme, the wind was described by crews on the ground as in excess of 100 km/h (62 mph), with spot fires starting over 5 km (3.1 mi) ahead of the main fire front.[citation needed]

Firefighters described what they believed to be a tornado generated by the fire storm, which began flattening trees and flipped a small fire vehicle. The tornado then impacted a crew of firefighters working to protect a property, flipping their tanker over and trapping the crew inside, who were then overrun by fire. One firefighter was killed with multiple others injured, with one airlifted to Melbourne and two to Sydney.[181][182][183][184][185][186]

Snowy Mountains

[edit]The Dunns Road fire was believed to have been started by a lightning strike on 28 December in a private pine plantation near Adelong.[187][188] In the Snowy Valleys local government area, by 2 January 2020 the Dunns Road fire had burnt south of the Snowy Mountains Highway in the Ellerslie Range near Kunama. Over 130,000 hectares (320,000 acres) was burnt and the fire was out of control. The NSWRFS issued an evacuation order to residents in the Adelong, Talbingo, Batlow and Wondalga areas. Residents and visitors to the Kosciuszko National Park were evacuated and the national park was closed. Many of the towns in the area were cut off from utilities for days after the fires went though the area. Also 155 inmates from the Mannus Correctional Centre near Tumbarumba were evacuated.[189][190][191][192]

On 3 January 2020, the Dunns Road fire burnt from Batlow into Kosciuszko National Park, burning much of the northern part of the park. Witnesses reported that an ember storm was jumping many km ahead of the fire front. The fire caused significant damage, severely damaging the Selwyn Snow Resort, destroying structures in the town of Cabramurra and almost completely destroying the heritage-listed precinct (and birthplace of skiing in Australia) of Kiandra. Kiandra's historic former courthouse[193] was left with only its walls standing after a fire so hot that the glass and aluminium in the windows melted.[194] A number of high country huts, including Wolgal Hut and Pattinsons Hut near Kiandra, were also feared to have been destroyed.[195] By 11 January three fires had merged – the Dunns Road fire, the East Ournie Creek, and the Riverina's Green Valley fire – and had created a 600,000-hectare (1,482,632-acre) "mega-fire", burning south of the Snowy Mountains.[196]

On 23 January 2020, a Lockheed C-130 Hercules large air tanker crashed near Cooma while waterbombing a blaze, resulting in the death of the three American crew members on board.[48][83]

On 1 February 2020, emergency warnings were issued for the Orroral fire and the Clear Range fire threatening Bredbo north of Cooma.[197]

Victoria

[edit]On 21 November 2019, lightning strikes ignited a series of fires in East Gippsland, initially endangering the communities of Buchan, Buchan South and Sunny Point.[198] On 20 December, the Marthavale-Barmouth Spur expanded, greatly endangering the community of Tambo Crossing.[citation needed]

The first day of two-day cricket tour match between a Victoria XI and New Zealand in Melbourne was cancelled due to extreme heat conditions.[199]

On 30 December 2019, there were three active fires in East Gippsland with a combined area of more than 130,000 hectares (320,000 acres), and another in the north-east of the state near Walwa heading south-east towards Cudgewa.[citation needed] An evacuation warning was issued for the East Gippsland town of Goongerah, which is surrounded by high-value old growth forests, as well as Cudgewa.[citation needed] On the same day, a fire broke out in the Plenty Gorge Parklands, situated in Melbourne's north-eastern suburbs between Bundoora, Mill Park, South Morang, Greensborough and Plenty.[200][201]

Fires reached the town of Mallacoota by around 8 am AEDT on 31 December 2019. At 11 am AEDT 31 December, fires had begun to approach the vacation town of Lakes Entrance.[202] Despite the recommendation that large portions of East Gippsland be evacuated, approximately 30,000 holiday makers chose to remain in the region. Approximately 4,000 people, including 3,000 tourists, remained in Mallacoota as the fire began making its closest approach to the town, cutting off roads in the process; Mallacoota had not been issued with an evacuation warning on 29 December.[203][failed verification] On 3 January, approximately 1,160 people from Mallacoota were evacuated on naval vessels HMAS Choules and MV Sycamore.[204][205] In the rural hamlet of Sarsfield 200 of the 276 properties in the area were impacted by fire with 73 dwellings lost and 49.2% of the landscape burnt.

On 2 January 2020 at 11 pm AEDT, Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews declared a state of disaster under the provisions of the Victorian Emergency Management Act for the shires of East Gippsland, Mansfield, Wellington, Wangaratta, Towong, and Alpine, and the alpine resorts of Mount Buller, Mount Hotham, and Mount Stirling. Emergency Management Commissioner Andrew Crisp stated that 780,000 hectares (1,900,000 acres) had burnt including 100,000 hectares (250,000 acres) near Corryong in the state's north-east and that fifty fires were burning.[206] On 3 January, Andrews said two people were confirmed dead from the East Gippsland fires.[207]

On 6 January 2020, Andrews said that bushfires had burnt through 1.2 million hectares (3 million acres) in Victoria's east and north-east and that 200 homes were confirmed lost.[208]

On 13 January 2020, two bushfires were burning at emergency level in Victoria despite milder conditions, one about 8 km east of Abbeyard and the other in East Gippsland affecting Tamboon, Tamboon South and Furnel.[209]

On 23 January 2020, there were still 12 fires burning in Victoria, the strongest in East Gippsland and the north-east. The Buldah fire in East Gippsland was at watch and act level and the rest were on advice level. Most of the 44 fires sparked by dry lightning were quickly dealt with by firefighters. Heavy rain in the Melbourne region brought little relief to bushfire-affected regions. Andrews said that the rains could bring new dangers for firefighters, including landslides.[210]

On 30 and 31 January 2020, very hot weather occurred in Victoria, New South Wales and South Australia that brought high fire danger with several uncontrolled bushfires still burning. An Emergency Warning was issued for Bendoc, Bendoc Upper, and Bendoc North on 30 January.[211]

On 20 February 2020, the huge East Gippsland bushfire that had burned for three months was declared "contained" by Bairnsdale incident controller Brett Mitchell. Recent rainfall also contributed to the Omeo, Anglers Rest, Cobungra, Bindi, Hotham Heights, Glen Valley, Benambra, Swifts Creek, Omeo, Ensay, Tongio, the Blue Rag Range, Dargo and Tabberabbera bushfires all being contained. The Snowy complex fire in the far east was the single major remaining fire still burning in Victoria.[212]

All significant fires in Victoria, including the Snowy Complex fire, were declared contained on 27 February 2020.[213]

Queensland

[edit]

On 7 September 2019 multiple out of control blazes threatened townships across south-eastern and northern Queensland, destroying eleven houses in Beechmont, seven houses in Stanthorpe, and one house at Mareeba.[214] On the following day the heritage-listed lodge and cabins at the iconic Australian nature-based Binna Burra Lodge were destroyed in the bushfire that consumed residential houses in Beechmont the previous day.[215]

A large fire impacted the Peregian Beach area on 9 September, on the Sunshine Coast, severely damaging ten houses.[216] In December 2019, Peregian Springs and the surrounding areas came under threat by bushfires for the second time in a couple of months. No homes in Peregian Springs area were confirmed lost in this bushfire.[217]

Due to deteriorating fire conditions and fires threatening homes across the state, on 9 November a State of Fire Emergency was declared across 42 local government areas across southern, central, northern and far-northern Queensland.[218] 14 homes were destroyed in the Yeppoon area during mid November 2019.[219]

On 27 October a fire started in inaccessible Defence land at the Canungra Military Area. Firefighters attempted to contain the fire with extensive water bombing until weather conditions improved. On 8 November, the fire broke through the containment line and impacted 30 houses in Lower Beechmont, resulting in the evacuation of the village. All houses were saved, though a shed and several outbuildings were lost.[220]

On 11 November a fire started in the Ravensbourne area near Toowoomba, which burnt through over 20,000 hectares (49,000 acres) of bush across several days, destroying six houses.[221] At 8 am the air quality in Brisbane reached unprecedentedly poor levels (Woolloongabba PM2.5 238.8 μg/m3). Queensland's chief health officer, Dr Jeannette Young, urged residents to stay indoors and to not physically exert themselves.[222]

On 13 November a water bombing helicopter crashed while fighting the blazes threatening the small community of Pechey. While the Bell 214 helicopter was completely destroyed, the pilot walked away with minor injuries.[223]

On 23 November the state of fire emergency was revoked and extended fire bans were put in place in local government areas that were previously affected under this declaration.[citation needed]

On 6 December a house fire broke out in Bundamba and quickly spread to nearby bushland and was placed under a watch and act alert by the Queensland Fire and Emergency Services that afternoon. The following day, after worsening conditions, the fire was upgraded to an emergency warning and began to threaten homes in the local community. The fire destroyed a shipping container filled with fireworks, and residents within the 3-square-kilometre (1.2 sq mi) exclusion zone were ordered to evacuate. One home was destroyed.[224]

On 8 November a bushfire broke out in forestry to the west of the township of Jimna, causing Queensland Fire and Emergency services to issue a "watch and act" alert. The fire caused the evacuation of the entire town.[225]

South Australia

[edit]On 11 November 2019 an emergency bushfire warning was issued for Port Lincoln in the Eyre Peninsula, with an uncontrolled fire travelling towards the town. The South Australian Country Fire Service ordered ten water bombers to the area to assist 26 ground crews at the scene. SA Power Networks disconnected power to the town.[226]

A large fire broke out on Yorke Peninsula on 20 November 2019 and threatened the towns of Yorketown and Edithburgh.[227] It destroyed at least eleven homes and burnt approximately 5,000 hectares (12,000 acres). The fire was believed to have started from a sparking electrical transformer.[228] A Boeing 737 water-bombing aircraft from New South Wales in addition to South Australian Air Tractor AT-802s were used to protect the town of Edithburgh.[229]

On 20 December fires took hold in the Adelaide Hills, and near Cudlee Creek in the Mount Lofty Ranges.[230] Initial south-easterly winds put the towns of Lobethal and Lenswood in the line of the fire, and by the next morning the winds had changed to north-north-west, threatening other towns.[231] The fires killed one person,[232] more than 70 houses were destroyed, as well as over 400 outbuildings and 200 cars.[233] Yearly Christmas celebrations at Lobethal were cancelled.[234] volunteers from around the Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges areas responded to the unfolding incident; this resulted in a number of fire trucks being overrun by the fast moving fire. One of the trucks involved was Seaford 34. The crews were attempting to prevent the fire from crossing Croft Rd at Cudlee Creek when a wind change pushed the fire front towards them. The crews took shelter in their truck until the fire front passed. The crews were taken back to Lobethal were they continued to assist community members whilst on foot with asset protection as the fire front moved through. Also on 20 December, an out-of-control bushfire took hold near Angle Vale, starting from the Northern Expressway and burning through Buchfelde and across the Gawler River. At 11:07 am ACDT the fire was burning under catastrophic weather conditions and an emergency warning was issued for Hillier, Munno Para Downs, Kudla, Munno Para West and Angle Vale. One house was destroyed.[235]

Another emergency warning was issued on 3 January for a fire near Kersbrook. At its largest extent, the warning area overlapped with areas that a few days earlier had been in warnings for the Cudlee Creek fire. Water bombers delivered 21 loads in just over an hour before darkness fell, and 150 firefighters on 25 trucks plus bulk water carriers and earthmoving equipment limited the advance of the fire to 18 hectares (44 acres).[236]

On Kangaroo Island starting in the Flinders Chase National Park, the Ravine bushfire burnt in excess of 15,000 hectares (37,000 acres) and a bushfire emergency warning was issued on 3 January 2020 as the fire advanced towards Vivonne Bay and the town of Parndana was evacuated.[237][238] On 4 January it was confirmed at least two people died.[239] As of 6 January 2020[update] approximately 170,000 hectares (420,000 acres), representing about a third of the island, had been burnt. Fires remained burning out of control, with firefighters working to contain and control fires before potentially hot windy weather scheduled for later in the week. Following fire damage to a water treatment plant, residents were asked to conserve water and some water was carted into island towns. There were concerns for the future of threatened wildlife, such as glossy black cockatoos, Kangaroo Island dunnarts, and koalas. Authorities stated that any koalas taken to the mainland for treatment cannot return to the island in case they bring diseases back with them.[i][240]

Western Australia

[edit]

Two bushfires burnt in Geraldton on 13 November, damaging homes and small structures.[241][242]

A fire broke out in Yanchep at 2:11 pm on 11 December, immediately triggering an emergency warning for Yanchep and Two Rocks. The fire led to a service station exploding.[243] On 12 December, temperatures in excess of 40 °C (104 °F) exacerbated the fire, and the emergency warning area doubled including parts of Guilderton and Brenton Bay further north.[244][245] On 13 December, increased temperature conditions resulted in the fire burning in excess of 5,000 hectares (12,000 acres), with the fire front over 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) in length. As of 13 December 2019[update], the emergency warning area stretched from Yanchep north to Lancelin over 40 km (25 mi) away.[246] By 16 December, the fire was considered contained and the alert downgraded to watch and act.[247] Approximately 13,000 hectares (32,000 acres) were burnt; only two buildings were damaged, both within the first day of the fire starting.[247]

In December fires in the region around Norseman blocked access to the Eyre Highway and the Nullarbor Plain and caused the highways of the region to be blocked,[248] so as to prevent any recurrence of the 2007 death of truck drivers on the Great Eastern Highway.[249][250]

Between 26 December 2019 and 1 January 2020, as a result of a lightning strike,[251] a fire tore through 40,000 hectares (99,000 acres) of land in Stirling Range National Park in the southwest of the state, burning more than half of the park.[252] The pyrocumulus cloud from the fires could be seen 80 km (50 mi) south in Albany.[253] By New Year's Day 2020 a crew of 200 firefighters brought the fire back to advice level without any loss of life or major property damage (a park ranger hut and hiking tracks were destroyed).[253] However, conservationists raised concerns for the potential loss of rare and unique flora and fauna that live in the park, which contains over 1500 such species within its boundaries, including a rare population of quokkas (one of few in mainland Western Australia).[252] A local politician, firefighters, farmers and tourism operators called on Western Australian Emergency Minister Fran Logan to invest in local firefighting assets for the area to make sure the tourist destination was properly protected.[253]

The last fire of Western Australian 2019–20 bushfire season started in Lake Clifton, within the Shire of Waroona, on 2 May and was extinguished on 3 May.[254] The Lake Clifton area was severely damaged during the 2010–11 bushfire season.[255]

Tasmania

[edit]In late October 2019, four bushfires were burning near Scamander, Elderslie, and Lachlan. Emergency warnings were issued at Lulworth, Bothwell, and Lachlan. A large fire near Swansea also burnt over 4,000 hectares (9,900 acres). Lightning strikes subsequently started multiple fires in Southwest Tasmania.[256][257] On 20 December 2019, a fire was started in the north east, which spread to 15,000 hectares (37,000 acres) and destroyed one home; a man was charged with starting the fire.[258]

Two fires continued to burn in January 2020. A fire in the Fingal Valley, in north-eastern Tasmania, started on 29 December, and a fire at Pelham, north of Hobart, started on 30 December. As of 16 January 2020[update] the Fingal fire had burnt over 20,000 hectares (49,000 acres) and the Pelham fire over 2,100 hectares (5,200 acres).[259][260]

Australian Capital Territory

[edit]

In the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), the national capital Canberra was blanketed by thick bushfire smoke on New Year's Day from bushfires burning nearby in New South Wales. That day the air quality in the capital was the worst of any city in the world, at around 23 times the threshold to be considered hazardous. Conditions continued the next day, and Australia Post stopped postal deliveries in the ACT to keep workers safe from smoke.[261][262] The first death directly linked to the poor air quality was also recorded on 2 January. An elderly woman had been travelling from Brisbane to Canberra by plane. When she exited the plane onto the smoke-flooded tarmac, she suffered respiratory distress and then died.[263] On 2 January 2020, the ACT declared a state of alert;[264] that was extended on 12 January as the merged Dunns Road fire burnt seven kilometres (four miles) from the Territory's south-west border.[265] Smoke from nearby bushfires continued to severely impact Canberra's air quality intermittently throughout January 2020.

From at least 6 January 2020 a bushfire near Hospital Hill in the Namadgi National Park had started; it was extinguished on 9 January.[266]

On 22 January 2020 a bushfire started in Pialligo Redwood Forest; it reached emergency level, threatening Beard and Oaks Estate. The next day a second bushfire started, the Kallaroo Fire, which later during the day merged with the Redwood Forest fire forming the Beard Fire; the fire jumped the Molonglo River and threatened the suburbs of Beard, Harman and Oaks Estate as it burnt 424 hectares (1,050 acres). Canberra Airport was closed for a day.[267][268][269] The fire destroyed one facility, four outbuildings, and three vehicles.[270]

On 27 January 2020 a bushfire started in the Orroral Valley in the Namadgi National Park. At 1:30 pm, an Army MRH-90 Taipan helicopter conducting reconnaissance for landing sites for remote area firefighting teams attempted to land for a break when their landing light ignited a fire in dry grass.[271][272][273] The aircrew waited until landing at Canberra Airport at about 2:15 pm to notify the ACT Emergency Services Agency meanwhile a fire tower had spotted white smoke at 1:49 pm and a search had commenced to locate the fire.[271] By the morning of 28 January the fire had grown to 2,575 hectares (6,360 acres) and was 9 kilometres (5.6 mi) from the town of Tharwa.[274][275] An emergency warning was declared for Tharwa and the southern suburbs of Canberra – particularly Banks, Gordon, and Conder — just after 1:30 pm AEST on 28 January. Chief Minister Andrew Barr described the fire as the biggest threat to Canberra since the 2003 Canberra bushfires.[276][272] At midday on 31 January, Barr declared a state of emergency for the ACT, the first time such action had occurred since the 2003 fires.[277] As the Orroral Valley Fire burned out of control, many instances of ‘disaster tourism’ were reported from suburban south Tuggeranong, with people driving to the suburbs to see the fire and take photographs; in turn blocking traffic.[278] The Orroral Valley fire was downgraded to "advice" status on 5 February and declared to be out on 27 February.[279]

Northern Territory

[edit]The Northern Territory went through a relatively average annual bushfire season with respect to area of land burnt, in comparison to the scale of bushfires witnessed in other areas of Australia. Despite this, approximately 6.8 million hectares (17 million acres) was burnt, an area which contributed significantly to the total area burnt by bushfires in the nation. Five homes were lost to bushfires in the Territory.[280]

Precedents

[edit]There have been a number of large scale bushfires recorded in Australian history. The widespread 1938–1939 fires in Victoria, NSW, South Australia and the ACT similarly gained international headlines when the fires entered the Sydney suburbs,[281] as did the 1994 eastern seaboard fires. The 1851 Black Thursday bushfires shocked colonial Australia with their ferocity, burning a quarter of what is now Victoria (around 5 million hectares (12 million acres)).[282] Lesser known is that about 117 million hectares (290 million acres), or 15 per cent of Australia's land mass, experienced fire in the summer of 1974–5. NSW was again badly affected, and three people killed. However, the fires were mainly in sparsely populated inland areas.[56] The five most deadly blazes were: Black Saturday 2009 in Victoria (173 people killed, 2000 homes lost); Ash Wednesday 1983 in Victoria and South Australia (75 dead, nearly 1900 homes); Black Friday 1939 in Victoria (71 dead, 650 houses destroyed), Black Tuesday 1967 in Tasmania (62 people and almost 1300 homes); and the Gippsland fires and Black Sunday of 1926 in Victoria (60 people killed over a two-month period).[283]

Nationally, Australian National University described the 2019 fire year as "close to average"[284] and the 2020 fire year as "unusually small".[285]

Environmental effects

[edit]

In mid-December 2019, a NASA analysis revealed that since 1 August, the New South Wales and Queensland bushfires had emitted 250 million tonnes (280 million short tons) of carbon dioxide (CO2).[286] A September 2021 study using satellite data estimated the CO2 emissions of the fires from November 2019 to January 2020 to be ~715 million tons,[37][38][39] about twice as much as earlier estimates.[35][36] By comparison, in 2018, Australia's total carbon emissions were equivalent to 535 million tonnes (590 million short tons) of CO2, – the greenhouse gas emissions surpassed Australia's normal annual bushfire and fossil fuel emissions by ~80%.[286] While the carbon emitted by the fires would normally be reabsorbed by forest regrowth, this would take decades and might not happen at all if prolonged drought has damaged the ability of forests to fully regrow.[286]

In December 2019, the air quality index (AQI) around Rozelle, an inner suburb of Sydney, hit 2,552 or more than 12 times the hazardous level of 200.[287] The level of fine particle matters, known and measured globally as PM2.5, around Sydney was also measured at 734 micrograms (0.01133 gr) or the equivalent of 37 cigarettes.[288] On 1 January 2020, the AQI around Monash, a suburb of Canberra, was measured at 4,650, or more than 23 times hazardous level and peaked at 7,700.[289]

On New Year's Day 2020 in New Zealand, a blanket of smoke from the Australian fires covered the whole South Island, giving the sky an orange-yellow haze. People in Dunedin reported smelling smoke in the air.[290] The MetService stated that the smoke would not have any adverse affects on the weather or temperature in the country.[290][291] The smoke moved over the North Island the following day, but began breaking up and was not as intense as it was over the South Island the previous day; meanwhile, wind from the South Pacific Ocean dissipated the smoke over the South Island.[292] The smoke affected glaciers in the country, giving a brown tint to the snow.[293] On 5 January 2020, more smoke wafted over the North Island, turning the sky in Auckland orange.[294] By 7 January 2020, the smoke was carried approximately 11,000 kilometres (6,800 mi) across the South Pacific Ocean to Chile, Argentina,[33][34] Brazil, and Uruguay.[295]

Ecological effects

[edit]Prof. Chris Dickman, a fellow of the Australian Academy of Science from the University of Sydney, estimated on 8 January 2020 that more than one billion animals were killed by bushfires in Australia; while more than 800 million animals perished in New South Wales. The estimate was based on a 2007 World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) report on impacts of land clearing on Australian wildlife in New South Wales that provided estimates of mammal, bird and reptile population density in the region. Dickman's calculation had been based on conservative estimates and the actual mortality could be higher. The figure provided by Dickman included mammals (excluding bats), birds, and reptiles; and did not include frogs, insects, or other invertebrates.[296] Other estimates, which include animals like bats, amphibians and invertebrates, also put the number killed at over a billion.[297]

A 2020 study estimated that at least 3 billion terrestrial vertebrates alone were displaced or killed by the fires, with reptiles (which tend to have higher population densities in affected areas compared to other vertebrates) comprising over two-thirds of the affected, with birds, mammals, and amphibians comprising the other third.[298]

Ecologists feared some endangered species were driven to extinction by the fires.[299][300] Though bushfires are not uncommon in Australia, they are usually of a lower scale and intensity that only affect small parts of the overall distribution of where species live. Animals that survived a bushfire could still find suitable habitats in the immediate vicinity, which was not the case when an entire distribution is decimated in an intense event. Besides immediate mortality from the fires, there were on-going mortalities after the fires from starvation, lack of shelter, and attacks from predators such as foxes and feral cats that are attracted to fire-affected areas to hunt.[301] At least one species, the Kate's leaf-tailed gecko, had the entirety of its habitat burnt by the fires, while the long-footed potoroo had over 82% habitat burnt.[302] Many endangered species managed to persist through the fires, albeit with severely impacted populations that will not survive in the long-term without major human influence.[303] Species such as the Kangaroo Island micro-trapdoor spider and the Kangaroo Island assassin spider, feared extinct after the fires, have since been sighted.[304][305][306]

On Kangaroo Island, Australia's third-largest island and known as Australia's "Galapagos Island",[307] a third of the island was burnt. Large parts of the island are designated as protected areas and host animals such as sea lions, penguins, kangaroos, koalas, pygmy possums, southern brown bandicoots, Ligurian bees, Kangaroo Island dunnarts and various birds including glossy black cockatoos.[308] NASA estimated that the number of dead koalas could be as high as 25,000 or about half the total population of the species on the island.[309] A quarter of the beehives of the Ligurian honey bees that inhabited the Island were believed to have been destroyed.[308] Both the Kangaroo Island dunnart and Kangaroo Island subspecies of the glossy black cockatoo are endangered and are only found on Kangaroo Island. Before the fires, there were fewer than 500 Kangaroo Island dunnarts and about 380 Kangaroo Island glossy black cockatoos.[310][311]

The loss of an estimated 8,000 koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) caused concerns. They are considered vulnerable to extinction, though not functionally extinct.[312]

Due to the extremely dry conditions, some remnant areas of rainforest that—unlike most Australian vegetation—have not evolved and adapted to fire, were burnt in 2019–2020. This may have permanently reduced the extent of the 80-million year old rainforests, which were already scarce due to previous land clearing for agriculture and logging. Smaller, isolated remnant pockets of rainforest were totally destroyed and unlikely to recover, leading to local extinctions of rainforest flora and fauna. It was notable that the normally wet rainforest areas on the margins of schlerophyll forest, did not perform their usual role as a barrier to the spread of fire but were burnt.[313][314][315][316]

Moreover, the fires caused widespread phytoplankton blooms by causing oceanic deposition of wildfire aerosols, enhancing marine productivity.[317][318] While these increased oceanic carbon dioxide uptake, the amount – estimated to be slightly more than 152±83.5 million tons[318] – did not counterbalance the ~715 million tons[39] of CO2 the fires emitted.

Archaeological effects

[edit]Fire damaged 500-year-old rock art at Anaiwan in northern New South Wales, with the intense and rapid temperature change of the fires cracking the granite rock. This caused panels of art to fracture and fall off the huge boulders that contain the galleries of art.[319]

At the Budj Bim heritage areas in Victoria the Gunditjmara people reported that when they inspected the site after fires moved across it, they found ancient channels and ponds that were newly visible after the fires burned much of the vegetation off the landscape.[320][321]

After fire burnt out a creek on a property at Cobargo, NSW, on New Year's Eve, a boomerang carved by stone artefact was found.[322]

Domestic response

[edit]New South Wales

[edit]The New South Wales Rural Fire Service is the lead agency for bush fires in New South Wales and formed the bulk of the primary response to the fires, mobilising thousands of firefighters and several hundred firefighting vehicles. They were heavily supported by Fire & Rescue New South Wales, as well as the NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service and the Forestry Corporation of NSW, who hold jurisdiction over national parks and forests across the state respectively. Additional local firefighting resources were also used from agencies such as Air Services Australia and Sydney Trains.[45]

Numerous interstate agencies deployed firefighting resources into New South Wales, including several hundred firefighters from the Victorian Country Fire Authority,[323] along with crews from the Melbourne Metropolitan Fire Brigade,[324] the South Australian Country Fire Service,[325] the South Australian Metropolitan Fire Service,[325] the South Australian Department of Environment and Water,[325] and the Queensland Fire and Emergency Service.[326]

Despite the substantial loss of property and loss of life, firefighters as of January 2020 managed to save over 16,000 structures from direct fire impact in addition to countless lives.[327]

Multiple other New South Wales emergency services assisted in the response, including NSW Ambulance that provided ongoing pre-hospital care to victims of the fires including firefighters, NSW Police that worked to ensure public safety was maintained through road closures and evacuations and the NSW State Emergency Service that assisted with logistical support.[327] With brush-tailed rock-wallabies and much of the indigenous wildlife population in parts of New South Wales were left without food or water, the NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service airdropped approximately 1,800 kilograms (4,000 lb) vegetables on the known habitats.[328] A joint operation by the NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service and NSW Rural Fire Service was mounted to protect the critically endangered Wollemia pines growing in Wollemi National Park. Fire retardant was dropped from air tankers, and an irrigation system was installed on the ground by specialist firefighters, who were lowered into the area by winches from helicopters.[329][330]

Commonwealth

[edit]On 24 December 2019, the Morrison government announced that volunteer firefighters employed in the Commonwealth public service would be offered at least 20 working days paid leave.[331] On 29 December 2019, it announced that volunteer firefighters who have been called out for more than 10 days would be able to receive financial compensation.[332] On 4 January 2020, it announced that it would lease four waterbombing planes including two long-range DC-10s and two medium-range for use by state and territory governments.[333]

On 5 January 2020, the Prime Minister announced the establishment of the National Bushfire Recovery Agency, funded initially with A$2 billion, under the control of former Australian Federal Police Commissioner, Andrew Colvin.[334][335]

Military

[edit]On 5 December 2019, the Australian Defence Force (ADF) commenced Operation Bushfire Assist to support state fire services in logistics, planning, capability, and operational support. Activities the ADF has undertaken as part of the Operation have included Air Force aircraft transporting firefighters and their equipment interstate, Army and Navy helicopters transporting firefighters, conducting night fire mapping, impact assessments and search and rescue flights, use of various defence facilities as coordination and information centres and for catering and accommodation for firefighters, liaison between state and federal government services, reloading and refuelling for waterbombing aircraft, deployment of personnel to assess fire damage and severity, and provision of humanitarian supplies.[45]

On 31 December 2019, the Defence Minister announced the ADF would provide assistance to East Gippsland, in particular the isolated high-fire-risk town of Mallacoota, deploying helicopters including a CH-47 Chinook and C-27J Spartan military transport aircraft to be based at RAAF Base East Sale and two naval vessels, HMAS Choules and MV Sycamore, with the vessels also able to assist in south-east New South Wales if required.[45][336][337] On 1 January 2020, the ADF deployed additional military staff establishing the Victorian Joint Task Force 646 (Army Reserve 4th Brigade) and the following day the New South Wales Joint Task Force 1110 (Army Reserve 5th Brigade).[45] On 3 January 2020, HMAS Choules and MV Sycamore evacuated civilians from Mallacoota bound for Westernport.[45]

On 4 January 2020, following a meeting of the National Security Committee, the Morrison government announced a compulsory call-out of Army Reserve brigades to deploy up to 3,000 reserve personnel full-time to assist with in the Operation. Additionally, Defence announced that it would deploy HMAS Adelaide to support other Navy ships in evacuations and relief, as well additional Chinook helicopters and military transport aircraft to RAAF Base East Sale.[338][333] The same day, Chinook helicopters evacuated civilians from Omeo; and Spartan aircraft evacuated civilians from Mallacoota on 5 January.[45]

Community organizations

[edit]The response of volunteer organisations and charities was also considerable, with WIRES Wildlife Rescue working to rescue and treat injured wildlife,[339] Rapid Relief Team Australia raising money for victims, providing meals for firefighters and assisting with two bulk water tankers,[340] Team Rubicon Australia providing debris removal and helping with the cleanup of fire affected areas,[341][342] the Animal Welfare League fundraising and assisting injured animals,[343][344] and St John Ambulance Australia and Australian Red Cross providing support at evacuation centres across New South Wales.

On 1 December 2019 WWF-Australia launched the "Towards Two Billion Trees" plan to aid the koala bushfire recovery. It aims to stop excessive tree-clearing, protect the existing trees and forests, and restore native habitat that has been lost. The ten-point plan for the next ten years foresees to grow 1.56 billion new trees and save 780 million trees.[345][346]

On 4 January 2020 Architects Assist was established, representing over 600 Australian architecture firms providing their services pro bono to the individuals and communities affected by the bushfires (together with approximately 1500 architecture student volunteers).[347][348][349]

International response

[edit]Political figures from outside Australia including Donald Trump,[350] Cory Booker,[351] Hillary Clinton,[352] Al Gore,[352] Bernie Sanders,[352] Greta Thunberg,[353][354] and Elizabeth Warren[351] all publicly commented about the fires. People in the entertainment industry such as Tina Arena,[351] Patricia Arquette,[355] Cody Rhodes, Cate Blanchett,[355] Russell Crowe,[356] Ellen DeGeneres,[357] Selena Gomez,[358] Halsey,[352] Nicole Kidman,[355] Lizzo,[358] Bette Midler,[352] Pink,[358] Margot Robbie,[355] Paul Stanley,[352] Jay Park,[359] Jonathan Van Ness,[358] Phoebe Waller-Bridge,[355] and Rosé[360][361] also made statements about the fires. Some of the aforementioned people have also donated or raised funds.

On 4 January 2020, Queen Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh sent a message of condolence to Governor-General David Hurley, sending their "thoughts and prayers to all Australians at this difficult time". The Queen indicated in her message that she was "deeply saddened" to hear of the fires and their devastating impact on the country, and expressed her thanks to emergency service workers.[362] On 8 January 2020, Prince Charles issued a video message expressing his despair at the "appalling horror" of the fires.[363] The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge and the Duke and Duchess of Sussex also issued messages to Australia,[363] Crown Princess Mary of Denmark, who is of Australian heritage, published an open letter where she and her husband, Crown Prince Frederik, expressed their condolences to the victims and respect for the firefighters.[364]

International aid

[edit]- Canada

Four deployments totalling 87 Canadian firefighters were sent through the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre.[365][366] It was the first time since 2009 that Canadian personnel were deployed to Australia.[367] The Canadian government also sent a CC-17 plane of the Royal Canadian Air Force with 15 personnel on 27 January to further aid with transport and provide airlift support.[368]

- Fiji

The government of Fiji deployed the Fiji Military Forces humanitarian assistance and disaster relief platoon and engineers to assist in the bush fire rehabilitation.[369]

- France

On 6 January, French President Emmanuel Macron stated he could help out with the bushfires.[370] A team of five French firefighting experts arrived in Australia on 9 January to determine possible options for French and European support.[371]

- Indonesia

On 1 February, (Satuan Setingkat Peloton) SST Zeni, an Army engineering platoon unit, would be dispatched to Australia. A total of 38 personnel, consist of 26 army engineers, 6 Korps Marinir personnel, 4 Air Force facility construction personnel, and 2 TNI Medical Department personnel. The team landed in RAAF Base Richmond in New South Wales on the same day, according to the Indonesian Embassy on 3 February 2020, the troops will be deployed on the Blue Mountains area.[372][373][374]

- Japan

On 15 January, the Japanese government sent two C-130 aircraft of the JASDF, along with 70 other Self-Defense Force personnel to assist in transport and other efforts in combating the bushfires.[375] The aircraft left Komaki Air Base and flew to RAAF Base Richmond in New South Wales the next day.

- Malaysia

On 5 January, Malaysia offered its assistance through a statement by Deputy Prime Minister Wan Azizah Wan Ismail.[376] On 13 January, Malaysia officially deployed over forty firefighters to assist with the bushfires. Twenty others from government agencies would also be involved with the mission.[377]

- New Zealand

Over fifty New Zealanders were deployed to Australia in both direct fire fighting and support roles.[378] In January 2020, New Zealand also deployed elements of the Royal New Zealand Air Force and New Zealand Army including three NH90 helicopters, two Army combat engineer sections, and a command element.[379] A specialist six person animal disaster response team were deployed by non-profit Animal Evac New Zealand[380] on 8 January to New South Wales,[381] assisting with wildlife rescue and supported by SAFE.[382] The team was the first international specialist animal rescuers to arrive[383] and included vets, animal management officers as well as animal disaster and technical animal rescue experts. A second team of four arrived on 13 January.[384] The teams partnered with local wildlife centres[385] to successfully rescue and relocate several injured animals.[386][387][388] as well as advising residents in fire danger zones on their animal evacuation plans.[389]

- Papua New Guinea

The Government of Papua New Guinea offered to send 1,000 military and other personnel to Australia to assist with the response to the bushfires.[390] Australia accepted 100 Papua New Guinea Defence Force personnel.[391]

- The Philippines

The Philippine Red Cross pledged to donate $100K to Australia,[392] while various Filipino personalities pledged support for the victims of the bush fires.[393] The women-led Teduray people of Maguindanao initiated a sacred rain-making ritual for Australian victims, calling on the fire goddess Frayag Sarif's intercession to bring rain to the country.[394]

- Singapore

Singapore deployed two Chinook helicopters and 42 Singapore Armed Forces personnel stationed at Oakey Army Aviation Centre to RAAF Base East Sale in Victoria.[395]

South Korea

South Korean satellites were utilized to provide data and imaging at the request of the Australia Government. South Korea also pledged $1,000,000 in aid through the Red Cross.[1]

- United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates sent 200 volunteers from the Emirates Red Crescent to help fight the fire, including Emirati astronaut Sultan Al Neyadi.[396][397] A Twitter campaign and hashtag #mateshelpmates was launched by the Dubai Expo 2020 aiming to raise donations to help those affected by the fires in Australia.[398] To increase awareness, Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the world's tallest tower, lit up in solidarity with Australia.[399]

- United States

The United States deployed 362 firefighters, including 222 from the United States Department of the Interior, to Australia to help combat the fires. Firefighters from other parts of the US also helped with the fires.,[400][401][402] On 23 January, three US firefighters died in the crash of a C-130 fire fighting aircraft, north east of Cooma in New South Wales.[403]

- Other countries

Several other countries have offered assistance: