2nd Portuguese India Armada (Cabral, 1500)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2010) |

The Second Portuguese India Armada was assembled in 1500 on the order of King Manuel I of Portugal and placed under the command of Pedro Álvares Cabral. Cabral's armada famously discovered Brazil for the Portuguese crown along the way. By and large, the Second Armada's diplomatic mission to India failed, and provoked the opening of hostilities between the Kingdom of Portugal and the feudal city-state of Calicut. Nonetheless, it managed to establish a factory in the nearby Kingdom of Cochin, the first Portuguese factory in Asia.

Fleet

[edit]The first India Armada, commanded by Vasco da Gama, arrived in Portugal in the summer of 1499, in rather sorry shape. Half of his ships and men had been lost thanks to battles, disease, and storms. Although Gama came back with a hefty cargo of spices that would be sold at enormous profit, he had failed in the principal objective of his mission: to negotiate a treaty with Calicut, the spice entrepôt on the Malabar Coast of India. Gama managed, however, to open the sea route to India via the Cape of Good Hope and secured good relations with the African city-state of Malindi, a critical staging post along the way.

On King Manuel I's orders, arrangements were immediately made to begin the assembly of a second armada in Cascais. Determined not to repeat Gama's mistakes, this one was to be a large and well-armed fleet of 13 ships and 1500 men, laden with valuable gifts and diplomatic letters to win over the potentates of the east.

Many details of the composition of the fleet are missing. Only three ship names are known, and there is some conflict among the sources on the captains. The following list of ships should not be regarded as authoritative, but as a tentative list compiled from various conflicting accounts.

| Ship Name | Captain | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. uncertain | D. Pedro Álvares Cabral | admiral flagship probably a large 200+ ton carrack |  |

| 2. El Rei | Sancho de Tovar | vice-admiral large 200+ ton carrack. ran aground near Malindi on return |  |

| 3. uncertain | Nicolau Coelho | veteran of Gama's 1st (1497) Armada |  |

| 4. uncertain | Simão de Miranda de Azevedo |  | |

| 5. São Pedro | Pero de Ataíde | 70 ton carrack or square-rigged caravel captain sometimes nicknamed Inferno (Hell) |  |

| 6. uncertain | Aires Gomes da Silva | lost at Cape of Good Hope |  |

| 7. uncertain | Simão de Pina | lost at Cape of Good Hope |  |

| 8. uncertain | Vasco de Ataíde | lost at either Cape Verde or Cape of Good Hope often confused with Luís Pires in the chronicles |  |

| 9. uncertain | Luís Pires | privately owned by the Count of Portalegre damaged at Cape Verde, returned to Lisbon |  |

| 10. Nossa Senhora da Anunciação or Anunciada | Nuno Leitão da Cunha | 100 ton carrack or large caravel, fastest in the fleet privately owned by D. Álvaro of Braganza financed by Marchionni consortium |  |

| 11. unknown | Bartolomeu Dias | famous navigator, rounder of the Cape of Good Hope in 1488 destined for Sofala but was lost at Cape |  |

| 12. unknown | Diogo Dias | brother of Bartolomeu destined for Sofala but was separated at Cape and did not cross to India ended up roaming African coast, from Madagascar to the Red Sea. |  |

| 13. supply ship | Gaspar de Lemos or André Gonçalves | exact captain of this ship contested in sources destined to be scuttled and burnt along the way returned to Lisbon to announce discovery of Brazil |  |

This list is principally in concordance with Fernão Lopes de Castanheda's Historia,[1] João de Barros's Décadas,[2] Damião de Góis's Chronica,[3] the marginal gloss of the Relaçao das Naos, Diogo do Couto's list,[4] and Manuel de Faria e Sousa's Asia Portugueza.[5][note 1] The main conflict is with Gaspar Correia's Lendas da Índia, who omits Pêro de Ataíde and Aires Gomes da Silva, listing instead Braz Matoso and Pedro de Figueiró, and introduces André Gonçalves in addition to Lemos. Correia also identifies Simão de Miranda as vice-admiral and captain of Cabral's own flagship.[8][note 2] Neither of the two eyewitnesses—an anonymous Portuguese pilot and Pêro Vaz de Caminha—give a list of captains in their sources.

The Second Armada was to be headed by the Portuguese nobleman Pedro Álvares Cabral, a master of the Order of Christ. Cabral had no notable naval or military experience; his appointment as capitão-mor (captain-major) was largely politically motivated. The exiled Castillian nobleman Sancho de Tovar was designated vice-admiral (soto-capitão) and Cabral's successor should anything happen to him.[note 3]

Veteran pilot Pedro Escobar was given the overall technical command of the expedition. Other veterans of the first armada included captain Nicolau Coelho, pilot Pêro de Alenquer, and clerks Afonso Lopes and João de Sá. The famed navigator Bartolomeu Dias, who was the first to double the Cape of Good Hope, and his brother Diogo Dias, who had served as clerk on Gama's ship, also served as captains.

Most of the ships were either carracks (naus) or caravels, and at least one was a small supply ship, although details on names and tonnage are missing.[note 4] The Anonymous Pilot refers to only twelve ships, plus a supply ship.[10] At least two ships, Cabral's flagship and Tovar's El Rei, were said to be around 240 tons, that is, about twice the size of the largest ship in the first armada three years prior.

Ten ships were destined for Calicut (Malabar, India), while the two ships headed by the Dias brothers were destined for Sofala in East Africa and the supply ship was destined to be scuttled and burnt along the way.[note 5]

At least two ships were privately owned and outfitted: Luís Pires's ship was owned by Diogo da Silva e Meneses, Count of Portalegre, while Nuno Leitão da Cunha's Anunciada was owned by the king's cousin D. Álvaro of Braganza, and financed by an Italian consortium composed of the Florentine bankers Bartolomeo Marchionni and Girolamo Sernigi and the Genoese Antonio Salvago. The remainder belonged to the Portuguese crown.

Accompanying the expedition as translator was Gaspar da Gama, who was a Jew captured in Angediva by Vasco Gama, as well as four Hindu hostages from Calicut taken by Gama in 1498 during negotiations. Also aboard was the ambassador of the Sultan of Malindi, who had arrived at Portugal with Gama, and was set to return to Malindi with Cabral's expedition.

Other passengers on the expedition included Aires Correia, the designated factor for Calicut, his secretary Pêro Vaz de Caminha, Afonso Furtado, the designated factor for Sofala, and clerk Martinho Neto. Accompanying them on the trip was the royal physician and amateur astronomer, Master João Faras, who brought along the latest astrolabe and new Arabic astronomical staves for navigational experiments. One chronicler suggests that the knight Duarte Pacheco Pereira was also aboard.[note 6]

The fleet carried some twenty Portuguese degredados, who were criminal convicts who could fulfill their sentences by being abandoned along the shores of various places and exploring inland on the crown's behalf. Four of the degredados are known: Afonso Ribeiro, João Machado, Luiz de Moura, and Antonio Fernandes, who was also a ship carpenter.

Finally, the fleet carried eight Franciscan friars and eight chaplains, under the supervision of the head chaplain, Fr. Henrique Soares of Coimbra. They were the first Portuguese Christian missionaries to India.

There are three surviving eyewitness accounts of this expedition: (1) an extended letter written by Pêro Vaz de Caminha (possibly dictated by Aires Correia), written from Brazil on May 1, 1500, to King Manuel I; (2) the brief letter by Mestre João Faras to the king, also from Brazil; and (3) the account of an anonymous Portuguese pilot, first published in Italian in 1507 (commonly referred to as the Relação do Piloto Anônimo, sometimes believed to be the clerk João de Sá).

Mission

[edit]The priority of the mission was to secure a treaty with Zamorin's Calicut (Calecute, Kozhikode), the principal commercial entrepôt of the Kerala spice trade and dominant feudal city-state on the Malabar coast of India. Vasco da Gama's first armada had visited Calicut in 1498, but had failed to impress the elderly ruling Manivikraman Raja ('Samoothiri Raja'), the Zamorin of Calicut. As such, no agreements had been signed. Cabral's instructions were to succeed where da Gama had not, and to this end was entrusted with magnificent gifts to present to the Zamorin. Cabral was under orders to establish a feitoria (factory) in Calicut, which would be placed under Aires Correia.

The second priority, assigned to Bartolomeu and Diogo Dias, was to search out the East African port of Sofala, near the mouth of the Zambezi river.[13] Sofala had been secretly visited and described by the explorer Pêro da Covilhã during his overland expedition a decade earlier (c. 1487), and he identified it as the endpoint of the Monomatapa gold trade. The Portuguese crown was eager to tap into that gold source, but da Gama's armada had failed to find it. The Dias brothers were instructed to find and establish a factory at Sofala under designated factor Afonso Furtado. To this end, the brothers were likely also instructed to secure the consent of Kilwa (Quíloa), the dominant city-state of the East African coast and putative overlord of Sofala.

A minor objective included the delivery of a group of Franciscan missionaries to India. It is said that Vasco da Gama had misinterpreted the Hinduism he saw practiced in India as a form of "primitive" Christianity. He believed its peculiar characteristics were a result of centuries of separation from the mainstream church in Europe. As such, Gama recommended that missionaries be sent to India to help bring the practices of the "Hindu church" up to date with Roman Catholic orthodoxy. To this end, a group of Franciscan friars, led by Fr. Henrique Soares of Coimbra, joined the expedition.

As a final objective, the Second Armada was also a commercial spice run. The crown and private merchants who had outfitted the ships expected full cargoes of spices to return to Lisbon.

Suspected Brazilian mission

[edit]There has been some debate over whether Cabral also had secret instructions from the king to lay claim to the landmass of Brazil—or, more precisely, to swing as far west as possible to the Tordesillas line and claim whatever lands or islands might be discovered there for the Portuguese crown, before the Spanish did.[14] Among the pieces of evidence is an indication of an island in the area in a 1448 map of Andrea Bianco, apparently alluded to in the letter of Master João Faras; there is also the suggestion by Duarte Pacheco Pereira in his Esmeraldo de Situ Orbis that he had been sent on an expedition to a western landmass in 1498.[15] That is about the full extent of the evidence of intentionality and this claim is largely speculative.[16] There are various reasons to presume the existence of such instructions unlikely.

Spanish explorers had certainly been tending south at that time. Christopher Columbus had touched the coast of the South American mainland around Guyana in 1498 on his third trip. In late 1499, Alonso de Ojeda had discovered much of the Venezuelan coast[note 7] and in early 1500, Vicente Yáñez Pinzón and Diego de Lepe, via generous southerly swings from the Canary islands, had reached at least what is now Ceará, and perhaps went as far east as Cape of Santo Agostinho in Pernambuco. They had explored much of the northern Brazilian coast west of it. It is possible that the southerly Spanish tendencies were deliberate, aimed at securing more land for the Spanish crown.[note 8]

These expeditions (except for the Columbus' voyage in 1498), however, were too recent for their results to have been known in Lisbon before Cabral's departure in March 1500; indeed, they were unknown in Spain itself. It is very doubtful that the Portuguese were aware of them. Even if they were, it would not seem sensible for Cabral's Second Armada to be instructed to deviate from its original mission in India to pursue exploratory work which would be far more efficiently accomplished by smaller caravels.

Outward journey

[edit]On March 9, Cabral's expedition set out from the Tagus. Thirteen days later, on March 22, Cabral's armada reached the island of São Nicolau in the middle of a storm. The privately outfitted ship of Luís Pires was too damaged by the tempest to continue, and returned to Lisbon.[3][18][9][note 9]

From Cape Verde, Cabral went southwest. It is unknown why he chose such an unusual direction, but the most probable hypothesis is that he was simply following the wide arc in the South Atlantic to catch a favorable wind to carry them to the Cape of Good Hope. Navigationally, the arc is sensible. From Cape Verde, the ship would cut across the doldrums below the equator, catch the southwest-bound equatorial drift, and turn into the southbound Brazil Current that will carry them down to the horse latitudes (30°S), where the prevailing westerlies begin. The westerlies would easily carry the ships across the South Atlantic around the Cape of Good Hope. If instead of this arc, Cabral attempted to strike southeast from Cape Verde, it would go into the Gulf of Guinea. To reach the Cape from there would be a struggle, as Cabral would have had to sail against the southeasterly trade winds, as well as the Benguela Current.

How Cabral knew of this arc is unknown. Most likely, this was precisely the route followed by Gama on his first trip in 1497. The veterans of the first fleet—notably the pilots Alenquer and Escobar—would very likely have charted the same route for Cabral again.[note 10] Indeed, in the Lisbon archives, there is a draft of a document intended for Cabral that instructs him to strike in a southwesterly direction when he reaches the doldrums.[note 11]

Alternative hypotheses forwarded for Cabral striking southwest are that he was trying to reach the Azores to repair his storm-battered fleet, that he was searching for and rounding up missing tempest-tossed ships, or that it was an intentional attempt to discover if there was any land by the Tordesillas line.

Discovery of Brazil

[edit]

Cabral took the same path as Gama had, but made a slightly wider arc and went further west than Gama had. As a result, he hit upon the hitherto unknown landmass of Brazil. After nearly 30 days of sailing (44 since departure), on April 21, Cabral's fleet found the first indications of nearby land.[22] The next day, the armada caught sight of the Brazilian coast, seeing the outlines of a hill they named Monte Pascoal.

The armada anchored at the mouth of the Frade river the next day, and a group of local Tupiniquim Indians assembled on the beach. Cabral dispatched a small party, headed by Nicolau Coelho, in a longboat ashore to make first contact. Coelho tossed his hat in exchange for a feathered headdress, but the surf was too strong for a proper landing and opening of communication, so they returned to the ships.[23]

Strong overnight winds prompted the armada to lift anchor and sail some 10 leagues (45 km) north, finding harbor behind the reef at Cabrália Bay, just north of Porto Seguro. The pilot Afonso Lopes, while sounding in a rowboat, spotted a native canoe, captured the two Indians on board, and brought them back to ship. The language barrier prevented questioning, but they were fed and given cloth and beads. The cultural difference was apparent: the natives spat out their honey and cake and were deeply surprised upon seeing a chicken.[24]

The next day, on April 25, a party led by Coelho and Bartolomeu Dias went ashore, accompanied by the two natives. Armed Tupiniquim warily approached the beach, but upon a signal from the two natives, set down their bows, and allowed the Portuguese to land and collect water.

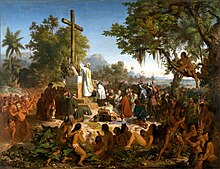

On April 26, the Octave of Easter Sunday, the Franciscan friar Henrique Soares of Coimbra went ashore to celebrate mass in front of 200 Tupiniquim Indians. This is the first known Christian mass on the American mainland.

Interaction between the Portuguese and the Tupiniquim gradually increased throughout the week. European iron nails, cloth, beads, and crucifixes were traded for American amulets, spears, parrots, and monkeys. There was only the slightest hint that precious metals might be found in the hinterlands. Portuguese degredados were assigned to spend the night in Tupiniquim villages, while the rest of the crew slept aboard ships.

On May 1, Cabral made preparations to resume the journey to India. The Portuguese pilots, assisted by the physician-astronomer Master João Faras, determined that Brazil lay east of the Tordesillas line, prompting Cabral to formally claim it for the Portuguese crown, bestowing upon it the name of Ilha de Vera Cruz ("Island of the True Cross"). It was later renamed Terra de Santa Cruz—"Land of the Holy Cross"—upon the realization that it was not an island.[note 12]

On May 2, Cabral dispatched the supply ship back to Lisbon, with the Brazilian items and a letter to King Manuel I composed by the secretary Pêro Vaz de Caminha to announce the discovery.[27] It also carried a separate private letter to the king from Master João Faras, in which he identified the main guiding constellation in the southern hemisphere, the Southern Cross (Cruzeiro).[note 13] The supply ship arrived in Lisbon in June.

After that, with a couple of Portuguese degredados left behind with the Tupiniquim of Porto Seguro,[27] Cabral ordered the eleven remaining ships to set sail and continue on their route to India.

Crossing to India

[edit]

After crossing the Atlantic Ocean, Cabral's armada reached the Cape of Good Hope in late May. The fleet faced headlong winds for six straight days and four ships—Bartolomeu Dias's, Aires Gomes da Silva's, Simão de Pina's, and Vasco de Ataíde's—were lost at sea in the process.[3][9][28][note 14] In this way, the fleet was reduced to seven ships. Facing strong winds, the armada split into smaller groups to meet again on the other side. Cabral's ship went with two others.

On June 16, 1500, Cabral's three-ship squadron reached the Primeiras Islands several leagues north of Sofala. Two local merchant ships, catching sight of Cabral, took flight. Cabral gave pursuit—one merchant ship ran aground and the other was captured. Upon questioning, it was discovered that these ships were owned by a cousin of the sultan Fateima of Malindi (who had received Vasco da Gama in 1498), so they were released.

The three ships landed on Mozambique Island on June 22. Despite the earlier quarrel the merchant ships, Cabral was given a warm reception by the Sultan of Mozambique and was allowed to collect water and supplies. Shortly after, three more ships of the Second Armada sailed into the island and joined with Cabral. Only the ship of Diogo Dias remained missing. As Dias's mission was for Sofala anyway, Cabral decided not to wait for it and instead pressed on with his fleet of six ships.

More than a month later, on July 26, Cabral's armada reached Kilwa, the dominant city-state of the East African coast and which Gama had never visited. Afonso Furtado, who had been appointed factor for Sofala in Lisbon and had escaped death (Furtado had been aboard Bartolomeu Dias's ship, but moved to the flagship just before the Cape crossing), went ashore to open negotiations with the strongman ruler, Emir Ibrahim.[note 15]

A meeting was arranged between Cabral and Ibrahim, conducted on a couple of rowboats in the harbor. Cabral presented a letter from King Manuel I proposing a treaty, but Ibrahim was suspicious and remained resistant to the overtures. Cabral, sensing Ibrahim's resistance and worrying that they might miss the monsoon winds to India, broke off the negotiations and sailed on.

Pressing north, the Cabral fleet avoided the hostile Mombassa (Mombaça) and finally reached friendly Malindi (Melinde) on August 2. There, he was well received by the Sultan of Malindi and dropped off the Malindi ambassador that Gama had taken the previous year. Leaving behind two degredados, Luís de Moura and João Machado, and picking up two Gujarati pilots, Cabral's six-ship armada finally began its Indian Ocean crossing on August 7, 1500.

Cabral in India

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2020) |

After an uneventful ocean crossing, Cabral's six ships landed on Anjediva Island (Angediva, Anjadip) on August 22, where they rested and repaired and repainted the ships.

Sailing down the Indian coast, Cabral's expedition finally reached Calicut on September 13. Gaily decorated native boats came out to greet them, but remembering Gama's experience, Cabral refused to go ashore until hostages were exchanged. He dispatched Afonso Furtado and the four Calicut hostages taken by Gama the previous year to negotiate the details of the landing. When the negotiation was complete, Cabral finally went ashore himself and met the new Zamorin of Calicut. Cabral presents him with much finer and more luxurious gifts than Gama had brought, and more respectful and personalized letters of address from King Manuel I of Portugal.

A commercial treaty was successfully negotiated and the Zamorin gave Cabral a security-of-trade certificate etched on a silver plate. The Portuguese were permitted to establish a feitoria in Calicut. Aires Correia went ashore with around 70 men. Once the factory was set up, Cabral released the ship hostages as a sign of trust and Correia set about buying spices in Calicut's markets for the ships to take home.

Sometime in October, the Zamorin of Calicut dispatched a service request to Cabral's idling fleet. Arab merchants allied with the rival city-state of Cochin were returning from Ceylon with a cargo of war elephants destined for the Sultan of Cambay. Claiming it to be illegal contraband, the Zamorin asked Cabral to intercept them. Cabral sent one of his caravels under Pêro de Ataíde to capture it. Hoping for a spectacle, the Zamorin himself came down to the beachfront to witness the engagement, but left in disgust when the Arab ship slipped past Ataide, who gave chase and eventually caught up to it near Cannanore. He successfully seized the vessel and Cabral presented the captured ship, with its nearly intact elephant cargo, to the Zamorin as a gift.

Calicut Massacre

[edit]By December 1500, factor Aires Correia was still only able to buy enough spices to load two of the ships. He complained to Cabral his suspicions that the guild of Arab merchants in Calicut had been colluding to shut out Portuguese purchasing agents from the city's spice markets. Arab traders had reportedly used similar tactics to drive out Chinese merchants earlier in the 15th century from various ports on the Malabar Coast. Correia thought that it would make sense if they repeated this, particularly as the Portuguese had been clear with their hatred of "the Moors" and had demanded trading privileges and preferences.[note 16]

Cabral presented Correia's complaint to the Zamorin, and requested that he crack down on the Arab merchant guild or enforce Portuguese priority in the spice markets. But the Zamorin refused Cabral's demand that he actively intervene in the market.

Frustrated by the Zamorin's inaction, Cabral decided to take matters into his own hands. On December 17, on the advice of Aires Correia, Cabral ordered the seizure of an Arab merchant ship from Jeddah, which had been loaded up with spices. He claimed that the Zamorin had promised the Portuguese priority in the spice markets, and so the cargo was rightfully theirs. Incensed, the Arab merchants around the quay immediately raised a riot in Calicut and direct mobs to attack the Portuguese factory. The Portuguese ships, anchored out in the harbor and unable to approach the docks, could only watch the unfolding massacre. After three hours of fighting, 53 (though some sources say 70) Portuguese were slaughtered by the mobs—including the factor Aires Correia, the secretary Caminha, and three (some say five) of the Franciscan friars. Around twenty Portuguese in the city managed to escape the riot by jumping into the harbor waters and swimming to the ships. The survivors reported to Cabral that the Zamorin's own guards were seen either standing aside or actively helping the rioters. At least one Portuguese, a man called Gonçalo Peixoto, was sheltered from the mob by a local merchant (whom the chronicles call "Coja Bequij") and survived the massacre.

After the Calicut massacre, the wares in the Portuguese factory were impounded by the Calicut authorities.

War with Calicut

[edit]Incensed at the attack on the factory, Cabral waited one day for redress by the Zamorin. When this did not arrive, Cabral and the Portuguese seized around ten Arab merchant ships then in harbor between December 18 and 22. They confiscated the ships' cargoes, killed the crews, and burned their ships. Then, accusing the Zamorin of sanctioning the riot, Cabral ordered a full day shore bombardment of Calicut, doing immense damage to the unfortified city. Estimates of Calicut casualties reach up to 600. Cabral proceeded to also bomb the nearby Zamorin-owned port of Pandarane.[note 17]

This marked the beginning of the war between the Kingdom of Portugal and the Zamorin of Calicut. The war dragged on for the next decade and became an important focus of future armadas. It ultimately dictated Portuguese strategy in the Indian Ocean and overturned the political order on the Malabar Coast of India.

Alliance with Cochin kingdom

[edit]On December 24, Cabral left the smoldering Calicut, unsure of what to do next. At the suggestion of Gaspar da Gama, the Goese Jew who had been accompanying the expedition, Cabral set sail south along the coast toward Cochin kingdom (Cochim, Kochi or Perumpadappu Swarupam), a small Hindu Nair city-state at the outlet of the Vembanad lagoon in the Kerala backwaters. Partly in vassalage to and partly at war with Zamorin's Calicut, Cochin had long chafed at the dominance of its larger neighbor and was looking for an opportunity to break away.

Arriving in Cochin, a Portuguese emissary and a Christian picked up in Calicut went ashore to make contact with the Trimumpara Raja (Unni Goda Varma), the Nair Hindu prince of Cochin.[note 18] The Portuguese were greeted warmly, with the bombardment of Calicut outweighing the earlier matter of the war elephants. With all the cordialities and hostage-swapping completed quickly, Cabral himself went ashore and negotiated a treaty of alliance between Portugal and Cochin, directed against Zamorin's Calicut. Cabral promised to make the Trimumpara Raja of Cochin the ruler of kingdom of Calicut upon the city's capture.

A Portuguese factory is set up in Cochin, with Gonçalo Gil Barbosa as chief factor. The spice markets of the smaller Cochin were not nearly as well-supplied as those of Calicut, but the trade was good enough to begin loading ships. The stay in Cochin was not, however, without incident. The factory was set ablaze one evening, likely at the instigation of Arab traders in the city. The Trimumpara Raja, in contrast with the Zamorin of Calicut, cracked down on the arsonists. He took the Portuguese under his protection by having the factors stay in his palace and assigned his personal Nair guards to escort the factors in the city markets and protect the factory against further incidents.

In early January 1501, while in Cochin, Cabral received missives from the rulers of Cannanore (Canonor, Kannur or Kolathunad), one of Calicut's reluctant rivals in the north, and Quilon (Coulão, Kollam or Venad Swarupam), which was further south and had once been a great Syrian Christian merchant city-state, being an entrepôt for cinnamon, ginger, and dyewood. They commended Cabral's actions against Calicut and invited the Portuguese to trade in their cities instead. Not wishing to offend his Cochinese host, Cabral declined the invitations, only promising to visit the cities at some future date.

While still in Cochin, Cabral received yet another invitation, this one from the nearby Cranganore kingdom (Cranganor, Kodungallur). The once-great capital of the Chera dynasty of Sangam period had recently been facing various natural disasters. The channels that connected Cranganore to the waterways were silted up, breaking open a competing sea outlet by Cochin in the 14th century.[note 19] Cochin's rise had been principally due to the re-routing of commercial traffic away from Cranganore. Nonetheless, the remaining merchants of the dwindling city still maintained their old connections to the Kerala pepper plantations in the interior. Finding the supply in Cochin running low, Cabral took up the offer to load some cargo at Cranganore.

The visit to Cranganore turned out to be an eye-opener for the Portuguese, for among the city's remaining inhabitants are substantial established communities of Malabari Jews and Syrian Christians. The encounter with a clearly recognizable Christian community in Kerala confirmed to Cabral what the Franciscan friars had already suspected back in Calicut, namely that Vasco da Gama's earlier hypothesis about a "Hindu Church" was mistaken. If real Christians had existed alongside Hindus in India for centuries, after all, then clearly Hinduism must be a distinct religion. Hindus were "heathen idolaters", as the Portuguese friars characterized them, rather than adherents to a "primitive" form of Christianity. Two Syrian Christian priests from Cranganore applied to Cabral for passage to Europe.[note 20]

On January 16, 1501, news arrived that the Zamorin of Calicut had assembled and dispatched a fleet of around 80 boats against the Portuguese in Cochin. Despite the Trimumpara Raja of Cochin's offer of military assistance against the Calicut fleet, Cabral decided to precipitously lift anchor and slip away rather than risk a confrontation. Cabral's armada left behind the factor Gonçalo Gil Barbosa and six assistants in Cochin. In their hasty departure, the Portuguese inadvertently took along two of the Trimumpara's officers (Idikkela Menon and Parangoda Mennon), who had been serving as hostages aboard the vessels.

Heading north, Cabral's armada took a wide sweep to avoid Calicut, and paid a quick visit to Cannanore. Cabral was warmly received by the Kolathiri Raja of Cannanore who, eager for a Portuguese alliance, offered to sell the Portuguese spices on credit. Cabral accepted the cargo but paid him nonetheless. Even though the cargo turned out to only be low-quality ginger, Cabral was appreciative of the gesture.

His ships now filled with spices, Cabral decided not to visit Quilon, as he had earlier promised, but to make way back home to Portugal instead.

Diogo Dias's misadventures

[edit]While Cabral's main fleet was in India, Diogo Dias, captain of the missing seventh ship of the armada, was going through his own set of adventures.

Shortly after being separated from the main fleet at the Cape in June 1500, Dias had struck out too far east into the Indian Ocean and sighted the western coast of the island of Madagascar. Although the island was not unknown (its Arab name, "island of the Moon", was already reported by Pero de Covilha), Dias was the first Portuguese captain to have sighted it and is often credited with renaming it the island of São Lourenço, on account of it being found on St. Lawrence's day (August 10, 1500). However, a proper landing on Madagascar would not be undertaken until 1506 and it would only be extensively explored in 1508.

Likely thinking that he was on a South African island, Dias tried to find the African coast by sailing straight north from Madagascar, hoping to reconnect with Cabral's armada there, or to make it to Sofala, Dias's official destination. But he had struck too far east and was in fact in open ocean. Dias sighted the African coast only around Mogadishu (Magadoxo), by which point Cabral had already crossed the Indian Ocean. The change in the monsoon winds prevented Dias from undertaking his own crossing. Dias pushed up the coast, unexpectedly passing Cape Guardafui into the Gulf of Aden, waters previously unexplored by Portuguese ships. Dias spent the next few months in the area. He was trapped by contrary winds, battered by tempests, attacked by Arab pirates, and forced aground on the Eritrean coast, unable to find food and water.

Eventually, in late 1500 and early 1501, Dias managed to procure supplies, repair his ship, and catch a favorable wind to take him out of the gulf. With his remaining six crewmen, Dias set sail back to Portugal, hoping to catch Cabral's armada on the return journey.

Return journey

[edit]In late January 1501, Cabral took aboard an ambassador from Cannanore and started his ocean crossing back to East Africa. On the way, the Portuguese captured a Gujarati ship, replete with a magnificent cargo. They stole the cargo, but, upon realizing that the crewmen were not Arabs, spared them.

As Cabral's expedition approached Malindi in February, vice-admiral Sancho de Tovar, sailing at the front, ran his spice-laden ship, the El Rei, aground on the Malindi coast. The great ship was irreparable. Its crew and cargo were reallocated, then the ship burnt to recover the iron fittings Cabral authorized the king of Malindi to recover the cannons from the wreck and keep them for himself.

Cabral's fleet, reduced to just five ships, reached Mozambique Island in the spring. As there was no news from Diogo Dias, Cabral decided to take responsibility for the Sofala mission himself. Cabral ordered the private ship Anunciada of Nuno Leitão da Cunha, the fastest in the fleet, to be placed under the command of veteran hand Nicolau Coelho. He dispatched it ahead of the rest of the fleet to deliver the results of the voyage to Portugal. Tovar took command of the caravel São Pedro, previously commanded by Pêro de Ataíde, with the intent to seek out Sofala and proceed home alone from there. Ataíde was transferred to the command of Coelho's old nau.

In the meantime, Cabral landed the degredado António Fernandes on the African coast, with letters of instruction for Diogo Dias and any passing Portuguese expeditions, informing them of the dramatic turn of events in India, and warning them to avoid Calicut. It is uncertain exactly where Cabral left António Fernandes or where he was ordered to go. According to Ataíde, Fernandes was ordered to go to Mombassa, which was odd, as Mombassa was at the time on hostile terms with the Portuguese; others suggest he was supposed to go to Kilwa (which is where the Third Armada of João da Nova eventually found him). Others have speculated that Fernandes was left in Kilwa on the outward leg, and that Cabral's letters were dispatched to him by a local messenger from Mozambique on the return. It is also possible that Fernandes had been instructed to make his way to Sofala overland, meet Tovar's ship there, and then proceed to explore inland from there to locate Monomatapa, though this does not explain why Cabral had given him the letters. Finally, some conjecture that Fernandes here is in fact another degredado, João Machado, who had been left in Malindi on the first leg. Machado, it is thought, may have been picked up on the return and was sent back once again with the letters.

Matters settled, Cabral took the remaining three ships—his own flagship, the large nau of Simão de Miranda, and Coelho's ship (now under Pêro de Ataíde)—and set sail out of Mozambique Island.

Ataíde became separated from the other two in the Mozambique Channel soon after departure. He hurried to São Brás, hoping to find Cabral there waiting for him. But Cabral and Miranda had decided to proceed on together towards Lisbon without him, so Ataíde made his way home alone, leaving behind a letter in a boot by a local watering hole giving an account of the expedition; Ataide's note would be found later that year by João da Nova's third armada.

In the meantime, Sancho de Tovar, aboard the São Pedro, finally caught sight of Sofala, the entrepôt of Monomatapa gold. He stayed in his ship, scouting the city from there, before setting sail back home alone.

Conference at Bezeguiche

[edit]In 1501, following up on the discovery of Brazil the previous year, King Manuel I of Portugal assembled a small exploratory expedition of three caravels under an unnamed Portuguese captain to explore and map the coast of Brazil. Aboard the ship was the Florentine cosmographer Amerigo Vespucci. The exact identity of the captain is uncertain. Some speculate it to have been the commander of the supply vessel that had delivered the news a year earlier (either Lemos or Gonçalves); others conjecture the commander went as a passenger and that the expedition itself was commanded by Gonçalo Coelho.[note 21] Setting out from Lisbon in May 1501, the expedition made a watering stop in early June at Bezeguiche, as the bay of Dakar, near present-day Senegal, was known to the Portuguese sailors of the time. There, they stumbled upon Diogo Dias, who related to the Portuguese captain and Vespucci the tales of his misadventures. Just two days later, the lead ship of the returning India fleet—the Anunciada under Nicolau Coelho—sailed into Bezeguiche, which must have been a pre-arranged point of encounter for the Second Armada, surprised to find both Dias and the Brazilian mapping expedition there.

For the next two weeks, the captains and crews of the different ships exchanged tales of their travels and adventures. It has been since speculated that it was during this time that Amerigo Vespucci came up with his "New World" hypothesis. After all, Vespucci was quite familiar with the Americas, having participated in Ojeda's 1499 expedition to the coasts of South America, and it is said he had intense discussions at Bezeguiche with Gaspar da Gama, undoubtedly the person most familiar with the East Indies. Comparing notes, it probably dawned on Vespucci that it was simply impossible to square what he knew of the Americas with what the men of the Second Armada knew of Asia. While still at Bezeguiche, Vespucci wrote a letter to Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici, relating his encounter, which he sent back with some Florentine passengers on the Anunciada.[38] This was a prelude to an even more famous letter of Vespucci to Lorenzo in 1503, shortly after his return, in which he asserts that the Brazilian landmass was in fact a continent and that the lands discovered to the west were definitely not part of Asia, but must be an entirely different continent, a "New World".[39][note 22]

In mid-June, Lemos and Vespucci left Bezeguiche for Brazil. Shortly after, Cabral and Simão de Miranda themselves reached Bezeguiche, where they find Diogo Dias and Nicolau Coelho awaiting them. Cabral sent Coelho's swift Anunciada ahead to Lisbon to announce their return, while the remainder rested and waited in Bezeguiche for the remaining two ships. Pêro de Ataíde's ship, making its way alone from Mossel Bay, and Sancho de Tovar's São Pedro, returning from Sofala, arrived in Bezeguiche by the end of June.

On June 23, the Anunciada, commanded by Nicolau Coelho, who had also been the first to deliver the news of Gama's expedition several years earlier, arrived in Lisbon and anchored in Belém. The merchants of the consortium led by Bartolomeo Marchionni, who own the Anunciada, were delighted. Letters were immediately fired off throughout Europe announcing the results.

The news arrived too late for João da Nova's 3rd India Armada, however, which departed for India in two months earlier in April. But Nova collected the necessary information along the way from the note in Ataíde's shoe in Mossel Bay, as well as from Cabral's letters in the possession of António Fernandes in Kilwa.

One month after Coelho's arrival, on July 21, Cabral and Miranda, captaining the two larger ships, finally arrived in Lisbon. The other three ships arrived a few days later: Tovar and Ataíde on July 25 and Dias, with his empty caravel, on July 27.

Aftermath

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2020) |

On the surface, Pedro Álvares Cabral's 2nd Armada had been a failure and the reaction was conspicuously muted.

The armada sustained heavy ship and human losses. Of the thirteen ships sent out, only five returned with cargo (four crown, one private). Three returned without any cargo (Gaspar de Lemos, Luís Pires, and Diogo Dias) and five were lost entirely. The crews and captains of the four ships lost at the Cape, including the famous navigator Bartolomeu Dias, also perished in the journey. Another fifty-something Portuguese, including the factor Aires Correia, had been killed in the Calicut massacre.

The expedition also failed to fulfill the mission of the expedition. Indeed, relative to the instructions given to him in Lisbon, Cabral had failed on nearly every count:

- 1. failed to establish a treaty with the Zamorin of Calicut—indeed, Calicut was now more hostile than ever

- 2. failed to establish a factory at Calicut (massacred)

- 3. failed to bring the 'Hindu Church' in line (the friars that survived reported the Hindus weren't Christians after all, just "idolaters")

- 4. failed to make a treaty with Kilwa

- 5. failed to establish a factory at Sofala (seen from afar by Tovar, but that is all)

However, Cabral's expedition accomplished much as well:

- 1. began friendly relations with Cochin, Canannore, and Quilon

- 2. opened a factory in Cochin, poorer than Calicut perhaps, but workable

- 3. discovered true Christian communities in Cranganore

- 4. discovered and scouted Sofala

- 5. discovered Brazil, which might serve as a useful staging post for future India runs

- 6. discovered Madagascar and explored the African coast up to Cape Guardafui and the Gulf of Aden by Diego Dias

- 7. brought back many spices, which were loaded into the Lisbon warehouses and sold at no small profit for the crown treasury

However, the ship and human losses weighed heavily against Cabral being honored or rewarded. Allegations of "incompetence" flew in the circles that mattered. Although Cabral was initially offered the command of the 4th Armada, scheduled for 1502, it seemed more like a pro forma gesture than a sincere offer.[40] The crown made it clear that Cabral's command would be limited and supervised—conditions humiliating enough to force Cabral to withdraw his name. The 4th Armada would ultimately be placed under the command of Vasco da Gama.

Although the reaction of Portuguese court opinion in 1501 upon Cabral's return was generally low, it ascended retrospectively. Cabral's discovery of Brazil, initially received as a minor discovery of little interest, turned out to be much more momentous. The follow-up Brazilian mapping expeditions of 1501–02 and 1503–04, under the captaincy of Gonçalo Coelho, carrying Amerigo Vespucci, revealed a massive continent which Vespucci famously labelled a "New World". The plenitude of brazilwood (pau-brasil) discovered by the mapping expeditions on its shores lured the interest of European cloth industry and led to the 1505 contract granted to Fernão de Loronha for the commercial exploitation of Brazil. The lucrative brazilwood trade eventually drew competition from French and Spanish interlopers, forcing the Portuguese government to take a more active interest in Cabral's "Land of Vera Cruz". This finally led to the establishment of the first Portuguese colonies in colonial Brazil in 1532.

See also

[edit]- Carta de Pêro Vaz de Caminha

- Portuguese India Armadas

- Portuguese India

- History of Brazil

- First Luso-Malabarese War

Notes

[edit]- ^ Both Barros and Gois mistakenly list Diogo Dias, Bartolomeu's brother, as "Pêro Dias", an error also found in the marginal gloss of the Relaçao das Naos[6] and subsequently repeated in Couto and Faria e Sousa. Oddly, Couto inserts Duarte Pacheco Pereira in place of Simão de Pina, but subsequently corrects himself. All the chroniclers—Castanheda, Barros, etc.—name Gaspar de Lemos instead of André Gonçalves. Chronicler Jerónimo Osório does not list captain names.[7]

- ^ This list conforms very closely with the original Relaçao das Naos, but not with its corrected marginal gloss.[6] The other great deviant is the Livro de Lisuarte d'Abreu (1563), which introduces four new names: Diogo de Figueiró, João Fernandes, Ruy de Miranda, and André Gonçalves, who replace P. d'Ataide, A. Gomes da Silva, S. da Pina, and G. de Lemos.

- ^ This is according to Castanheda and Damião de Góis. Gaspar Correia identifies Simão de Miranda as the predesignated successor instead.

- ^ Castanheda claims there were ten carracks and three caravels.[9]

- ^ The Sofala destination of the Dias brothers is found in Castanheda.[9] It is confirmed in the Anonymous Pilot.[10]

- ^ Damião de Góis is the chronicler responsible for this claim. This is not substantiated elsewhere.[11] Diffie and Winius dismiss the possibility.[12]

- ^ Amerigo Vespucci was a participant in this voyage and supposedly (according to his own words) independently explored part of the northern coast of Brazil, believing that he was sailing along the eastern edge of Asia.[17]

- ^ Although the person from whom the Spanish crown was trying to claim land was not the king of Portugal, as that was already mediated by Tordesillas, but Christopher Columbus, their own vice-roy of the Indies. Ojeda, Pinzón, and Lepe were all dispatched on separate royal capitulations by Bishop Fonseca, an enemy of Columbus, with the deliberate intent of finding and claiming lands outside (i.e., to the south) of the Columbus-owned West Indian islands, thereby circumscribing Columbus's viceroyalty and limiting him to the islands he already had. This would figure in later lawsuits by the Columbus family.

- ^ Caminha's eyewitness account made no mention of Pires and instead reported that it was the Vasco de Ataide's crown ship that was lost around Cape Verde.

- ^ That this arc was sailed by Gama in 1497 is uncertain, but most modern historians have come to accept that he did. How did Gama know about the arc when no one had yet sailed it before? Some have speculated that the Portuguese crown might have dispatched secret exploratory expeditions to those waters in advance. The more widely accepted hypothesis, first forwarded by admiral Gago Coutinho, is more straightforward: Since Bartolomeu Dias's 1488 expedition discovered the westerlies, the South Atlantic arc became "navigationally obvious" to any sensible pilot, especially pilots as experienced as Alenquer and Escobar.[19]

- ^ After Cape Verde, where the wind is weak ('vento escasso') the ships should strike in the open ocean arc ('ir na volta do mar'), until the Cape of Good Hope, as this is the shorter route ('a navegação será mais breve').[20][21]

- ^ Gaspar Correia and João de Barros say it was named "Santa Cruz" from the start,[25][26] with Correia saying it was named so because the departure date was the Feast of the Cross on the liturgical calendar. However, both Caminha's and Mestre João's letters are signed as written from "Vera Cruz" on May 1.

- ^ Some sources claim that the Cruzeiro constellation had already been identified by Alvise Cadamosto in the 1450s.[citation needed]

- ^ The Relaçao das Naos mistakenly substitutes Simão de Miranda for Simão da Pina in the losses, although this is corrected in the marginal gloss. Gaspar Correia almost concurs—but as he does not have Aires Gomes da Silva on his original captain list, he identifies the fourth ship lost as Gaspar de Lemos.[29] Similarly, the Livro de Lisuarte d'Abreu (1563), which has neither Pina nor Gomes da Silva on its list, say it was Diogo de Figueiró and Luis Pires who were lost. Diogo do Couto mistakenly adds Pêro d'Ataide to the list, bringing the losses to five.[30] Some scholars also contend that Pires was lost at this point, and Vasco de Ataíde had been lost earlier at Cape Verde.[citation needed]

- ^ At the time, there was no ruling Sultan of Kilwa as the previous one, al-Fudail, had been deposed in a coup (c. 1495) by his minister, Emir Ibrahim, who had since ruled Kilwa with a vacant throne.

- ^ Historians now think that the Portuguese traders may have in fact been unwitting counters in ongoing quarrels between competing older and newer Arab merchant guilds in Calicut. They may also have been used as pawns in the personal power struggles among the Zamorin's leading advisors.

- ^ The port of Pandarane has since disappeared. Its location is usually identified as 'Pantalyini Kollam', a port that has since been annexed by the growing city of Koyilandy; it is also sometimes identified with modern Kappad.[31]

- ^ The exact status of the Trimumpara Raja is a bit unclear. It seems that the formal ruler of Cochin was the king of Edapalli, which was across the lagoon on the mainland, but that the Cochinese peninsula (with capital at Perumpadappu) had at some point been detached as an appanage for a son, who, in turn, had detached the northern tip, Cochin proper, for another son. Moreover, it seems that these appanages were not supposed to be permanent fiefs, but rather to serve as temporary "training grounds" for princely heirs before they moved up in succession order. In other words, the ruler of Cochin was the second heir of Edapalli. Upon the death of the ruler of Edapalli, the first heir was meant to leave the peninsula and take up his duties in Edapalli, and the second heir would from Cochin to Perumpadappu, and assign Cochin to his own successor (the new second heir). The Portuguese seem to have arrived at a time when the princely heirs were somewhat at odds with one another, for some reason or another. It was only under Portuguese protection that the rulers of Cochin finally became proper kings in their own right. Thus the Raja Trimumpara's search for a Portuguese alliance possibly had more to do with his own family quarrels than with the exactions of the Zamorin of Calicut.[32]

- ^ Cochin was originally just a village along a long embankment. Violent overflows of the Periyar River in 1341 forced the opening of the outlet between the Vembanad lagoon and the Arabian Sea at the juncture where Cochin now sits, separating the long Cochinese peninsula from what is now Vypin island.[33]

- ^ One of these priests, known as José de Cranganore or Joseph the Indian (Josephus Indus), eventually would provide instrumental intelligence about India to the Portuguese. Upon arrival in Lisbon, Joseph the Indian spent a couple of years being intensely interviewed by the Portuguese court and the Casa da Índia, relating to them his detailed knowledge of the history and geography of India and the east, expanding Portuguese intelligence dramatically. It is likely that the detailed depiction of the east Indian coast and the Bay of Bengal in the Cantino planisphere of 1502 is owed in large part to this information. Around 1503, Joseph went to Rome to meet Pope Alexander VI and report on the condition of the Malabari Syrian Christian church. It was on this trip that Joseph dictated his famous narrative on India to an Italian scribe, which was eventually published in 1507 (in Italian) as part of a collection, Paesi Novamente Retrovati, edited by Fracanzio da Montalboddo. The narrative includes Joseph's own account of Cabral's expedition.[34]

- ^ Amerigo Vespucci wrote two detailed accounts of this expedition—in Mundus Novus (pub. 1502/03) and as the "third voyage" in Lettera a Soderini (pub. 1504/05)—but does not identify the Portuguese captain by name in either. Chronicler Gaspar Correia, writing a half-century later, identifies the mapping captain as the same captain who steered the returning supply ship. Greenlee suggests the captain was Fernão de Loronha,[35] although this has been dismissed by others.[36] More recently, historians have drawn attention to a nautical chart by Vesconte de Maggiolo, which identifies the Brazilian landmass with the label Tera de Gonsalvo Coigo Vocatur Santa Cruz (translated as "Land of Gonçalo Coelho called Santa Cruz"). Gonçalo Coelho is known to have led a later expedition to Brazil, which set out in 1503, but it is commonly estimated that Coelho was still out at sea when Maggiolo composed his chart (c. 1504-05), thereby suggesting that Coelho might have also captained the previous 1501 mapping expedition as well.[37]

- ^ After leaving Bezeguiche, the mapping expedition would make landfall at Cape São Roque in August 1501, and would proceed to sail south along the Brazilian coast, possibly as far as the São Paulo coast. They returned to Lisbon before September 1502, perhaps as early as June. A second mapping expedition, this time more certainly under Gonçalo Coelho, also accompanied by Vespucci (his "fourth voyage"), set out for Brazil in April 1503.

References

[edit]- ^ João de Barros (1552), p. 384, "Capitulo I".

- ^ a b c Damião de Góis (1566–1567), "Capitulo LIIII".

- ^ Diogo do Couto (c. 1600), p. 117.

- ^ Manuel de Faria e Sousa (1666), p. 44.

- ^ a b Maldonado (1985), p. 10.

- ^ Jerónimo Osório (1571).

- ^ Gaspar Correia (c. 1550), p. 148.

- ^ a b c d Castanheda (1551), p. [page needed].

- ^ a b [Anonymous Pilot] (1507), p. [page needed].

- ^ Greenlee (1938), p. li.

- ^ Diffie & Winius (1977), p. 188fn.

- ^ [Anonymous Pilot] (1507), p. 107.

- ^ Peres, Damião (1949). O descobrimento do Brasil por Pedro Álvares Cabral: antecedentes e intencionalidade (in Portuguese).

- ^ Pacheco Pereira, Duarte (c. 1505). "Cap 2: Da cantidade & grandeza da terra, & daugua qual destas he a mayor parte.". Esmeraldo de Situ Orbis (in Portuguese).

- ^ Greenlee (1938), pp. l–lv.

- ^ Vigneras 1976, p. 49.

- ^ João de Barros (1552), p. 386, "Capitulo II".

- ^ Gago Coutinho (1951–1952). A Nautica dos Descobrimentos: os descobrimentos maritimos visitos por um navegador. 2 vols. Lisbon: Agencia Geral do Ultramar.

- ^ Fonseca (1908), pp. 211, 224.

- ^ Greenlee (1938), p. 167.

- ^ Fonseca (1908), p. 225.

- ^ Fonseca (1908), pp. 241–242.

- ^ Narloch, Leandro (2011). Guia politicamente incorreto da História do Brasil (2nd ed.). São Paulo, Brasil: LeYa. OCLC 732793349.

- ^ Gaspar Correia (c. 1550), p. 152.

- ^ João de Barros (1552), p. 391, "Capitulo II".

- ^ a b [Anonymous Pilot] (1507), p. 110.

- ^ João de Barros (1552), p. [page needed].

- ^ Gaspar Correia (c. 1550), p. [page needed].

- ^ Diogo do Couto (c. 1600), p. [page needed].

- ^ Dames (1918), p. 85.

- ^ Dames (1918), p. 86n.

- ^ Hunter (1908), p. 360.

- ^ Vallavanthara (2001), p. [page needed].

- ^ Greenlee (1945).

- ^ Roukema (1963).

- ^ Morison (1974), p. 281, vol. 2.

- ^ Vespucci (1501).

- ^ Vespucci (1503).

- ^ Subrahmanyam (1997), p. 191.

Sources

[edit]Eyewitness Accounts

- [Anonymous Pilot] (1507). "Navigationi del Capitano Pedro Alvares Cabral Scrita per un Piloto Portoghese et Tradotta di Lingua Portoghese in Italiana". In Francanzano Montalbado (ed.). Paesi novamente retrovati et Novo Mondo da Alberico Vesputio Florentino intitulato. Vicenza.

- Reprinted in Venice (1550), by Giovanni Battista Ramusio, ed., Primo volume delle navigationi et viaggi nel qua si contine la descrittione dell'Africa, et del paese del Prete Ianni, on varii viaggi, dal mar Rosso a Calicut,& infin all'isole Molucche, dove nascono le Spetierie et la navigatione attorno il mondo. online (Port. transl. by Trigoso de Aragão Morato, as "Navegação do Capitão Pedro Álvares Cabral, escrita por hum Piloto Portuguez, traduzida da Lingoa Portugueza para a Italiana, e novamente do Italiano para o Portuguez.", in Academia Real das Sciencias, 1812, Collecção de noticias para a historia e geografia das nações ultramarinas: que vivem nos dominios portuguezes, ou lhes são visinhas, vol. 2, Pt.3

- Pêro Vaz de Caminha - Carta de Pêro Vaz de Caminha

Chronicles

- João de Barros (1552). "Decada I. Livro V.". Décadas da Ásia: Dos feitos, que os Portuguezes fizeram no descubrimento, e conquista, dos mares, e terras do Oriente (in Portuguese). pp. 378ff.

- Castanheda, Fernão Lopes de (1551). História do descobrimento & conquista da Índia pelos portugueses. Livro I (in Portuguese). 1833 reprint.

- Gaspar Correia (c. 1550). Lendas da Índia. Vol. 1. Lisbon: Academia Real das Sciencias (published 1858–1864).

- Diogo do Couto (c. 1600). "Capitulo XVI: De todas as Armadas que os Reys de Portugal mandáram à Índia, até que El-Rey D. Filippe succedeo nestes Reynos". Década déxima da Ásia. Livro 1 (in Portuguese). Lisbon: Régia Oficina Typografica (published 1788).

- Damião de Góis (1566–1567). "Capitulo LIIII: Da segunda armada que el Rei mandou à Índia, de que foi por Capitão Pedralveres Cabral". Chronica do Felicissimo Rei Dom Emanuel. Lisboa: casa de Françisco Correa. Fol. 51. OCLC 1041789487.

- Damião de Góis (1749). "Capitulo LIIII: Da segunda armada que el Rei mandou à Índia, de que foi por Capitão Pedralveres Cabral". In Reinerio Bocache (ed.). Chronica do serenissimo senhor rei D. Manoel. Lisboa: Na officina de Miguel Manescal da Costa. pp. 67–68. OCLC 579222983.

- Manuel de Faria e Sousa (1666). "Capitulo V: Conquistas del Rey D. Manuel desde el año 1500, hasta el de 1502". Asia Portuguesa (in Portuguese). Vol. I. Lisbon: Henrique Valente. pp. 44–50.

- Jerónimo Osório (1571). De rebus Emmanuelis.

- (Port. trans. 1804, Da Vida e Feitos d'El Rei D. Manuel. Lisbon: Impressão Regia.) p. 145ff)

- (Eng. trans. 1752 by J. Gibbs as The History of the Portuguese during the Reign of Emmanuel. London: Millar.)

- Relação das Náos e Armadas da India com os Sucessos dellas que se puderam Saber, para Noticia e Instrucção dos Curiozos, e Amantes da Historia da India (Codex Add. 20902 of the British Library), [D. António de Ataíde, orig. editor.] Transcribed & reprinted in Maldonado, M.H. (1985). Relação das Náos e Armadas da India com os Sucessos dellas que se puderam Saber, para Noticia e Instrucção dos Curiozos, e Amantes da Historia da India. Biblioteca Geral da Universidade de Coimbra.

- Vespucci, Amerigo (1501). "Letter to Lorenzo de' Pier Francesco de' Medici, from Bezeguiche, June, 1501". In F.A. de Varnhagen (ed.). Amerígo Vespucci: son caractère, ses écrits (meme les moins authentiques), sa vie et ses navigations. Original Italian version. Lima: Mercurio (published 1865). pp. 78-82.

- An English translation can be found in Greenlee (1938), pp. 151ff.

- Vespucci, Amerigo (1503). "Letter to Lorenzo de' Pier Francesco de' Medici, 1503/04". The Letters of Amerigo Vespucci and other documents illustrative of his career. Translated in 1894. London: Hakuyt society. p. 42.

Secondary

- Dames, M.L. (1918). "Introduction". An Account Of The Countries Bordering On The Indian Ocean And Their Inhabitants. Vol. 1 (2005 reprint ed.). New Delhi: Asian Education Services. (Engl. transl. of Livro de Duarte de Barbosa

- Diffie, B. W.; Winius, G. D. (1977). Foundations of the Portuguese empire, 1415-1580. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Fonseca, Faustino da (1908). "[copy of letter]". A Descoberta to Brasil (in Portuguese) (2nd ed.). Lisbon: Livraria Central de Gomes de Carvalho.

- Greenlee, William Brooks (1938). The Voyage of Pedro Álvares Cabral to Brazil and India: from contemporary documents and narratives. New Delhi: Asian Education Services. 1995 reprint. ISBN 1409414485.

- Greenlee, William Brooks (1945). "The Captaincy of the Second Portuguese Voyage to Brazil, 1501-1502". The Americas. Vol. 2. pp. 3–13.

- Hunter, W.W., ed. (1908). Imperial Gazetteer of India, Provincial Series, Vol. 18 - Madras II. Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing.

- Logan, W. (1887) Malabar Manual, 2004 reprint, New Delhi: Asian Education Services.

- Morison, S.E. (1974). The European discovery of America: the southern voyages A.D. 1492-1616. 2 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nair, K. Ramunni (1902) "The Portuguese in Malabar", Calcutta Review, Vol. 115, p. 210-51

- Pereira, Moacir Soares (1979) "Capitães, naus e caravelas da armada de Cabral", Revista da Universidade de Coimbra, Vol. 27, p. 31-134. offprint

- Peres, Damião (1949) O Descobrimento do Brasil por Pedro Álvares Cabral: antecedentes e intencionalidade Porto: Portucalense.

- Quintella, Ignaco da Costa (1839–42) Annaes da marinha portugueza. Lisboa.

- Roukema, E. (1963). "Brazil in the Cantino Map". Imago Mundi. Vol. 17. pp. 7–26.

- Russell-Wood, A.J.R. (1998) The Portuguese Empire 1415–1808: A world on the move. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Subrahmanyam, S. (1997). The Career and Legend of Vasco da Gama. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Vallavanthara, Anthony (2001). India in 1500 AD: The Narratives of Joseph the Indian. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press.

- Vigneras, Louis-André (1976). The Discovery of South America and the Andalusian Voyages. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226856094.

- Visconde de Sanches da Baena (1897) O Descobridor do Brazil, Pedro Alvares Cabral: memoria apresentada á Academia real das sciencias de Lisboa. Lisbon online

- Whiteway, Richard Stephen (1899) The Rise of Portuguese Power in India, 1497-1550 Westminster: Constable.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch