Ethiopian Empire

Ethiopian Empire | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1270–1974 1936–1941: Government-in-exile | |||||||||

| Motto: ኢትዮጵያ ታበፅዕ እደዊሃ ኀበ እግዚአብሔር Ityopia tabetsih edewiha ḫabe Igziabiher (English: "Ethiopia Stretches Her Hands unto God") (Psalm 68:31) | |||||||||

| Anthem: ኢትዮጵያ ሆይ ደስ ይበልሽ Ityoṗya hoy des ybelish (English: "Ethiopia, Be happy") | |||||||||

The location of the Ethiopian Empire during the reign of Yohannes IV (dark orange) compared with modern day Ethiopia (orange) The location of the Ethiopian Empire during the reign of Yohannes IV (dark orange) compared with modern day Ethiopia (orange) | |||||||||

| Capital | None[note 1] (1270–1635) Gondar (1635–1855) Debre Tabor (1855–1881) Mekelle (1881–1889) Addis Ababa (1889–1974) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Amharic (dynastic, official, court)[3][4] Ge'ez (liturgical language, literature) many others | ||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Endonym: Ethiopian Exonym: Abyssinian | ||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy (1270–1931)[5]

Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy (1931–1974) | ||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||

• 1270–1285 (first) | Yekuno Amlak[6] | ||||||||

• 1930–1974 (last) | Haile Selassie | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||

• 1909–1927 (first) | Habte Giyorgis | ||||||||

• 1974 (last) | Mikael Imru | ||||||||

| Legislature | None (rule by decree) (until 1931) Parliament (1931–1974)[7] | ||||||||

| Senate (1931–1974) | |||||||||

| Chamber of Deputies (1931–1974) | |||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages to Cold War | ||||||||

• Ascension of Yekuno Amlak | 1270 | ||||||||

• Conquests of Amda Seyon I | 1314–1344 | ||||||||

| 1529–1543 | |||||||||

| 1632–1769 | |||||||||

| 1769–1855 | |||||||||

| 1878–1904 | |||||||||

| 1895–1896 | |||||||||

| 16 July 1931 | |||||||||

• Second Italo-Ethiopian War (annexed into Italian East Africa) | 3 October 1935 | ||||||||

| 5 May 1941 | |||||||||

| 11 September 1952 | |||||||||

• Coup d'état by the Derg | 12 September 1974 | ||||||||

| 21 March 1975[8][9][10][11] | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1954 | 1,221,900 km2 (471,800 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Currency |

| ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Eritrea Ethiopia | ||||||||

The Ethiopian Empire,[a] historically known as Abyssinia or simply Ethiopia,[b] was a sovereign state[16] that encompassed the present-day territories of Ethiopia and Eritrea. It existed from the establishment of the Solomonic dynasty by Yekuno Amlak around 1270 until the 1974 coup d'état by the Derg, which ended the reign of the final Emperor, Haile Selassie. In the late 19th century, under Emperor Menelik II, the empire expanded significantly to the south, and in 1952, Eritrea was federated under Selassie's rule. Despite being surrounded by hostile forces throughout much of its history, the empire maintained a kingdom centered on its ancient Christian heritage.[17]

Founded in 1270 by Yekuno Amlak, who claimed to descend from the last Aksumite king and ultimately King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, it replaced the Agaw kingdom of the Zagwe. While initially a rather small and politically unstable entity, the Empire managed to expand significantly under the crusades of Amda Seyon I (1314–1344) and Dawit I (1382–1413), temporarily becoming the dominant force in the Horn of Africa.[18] The Ethiopian Empire would reach its peak during the long reign of Emperor Zara Yaqob (1434–1468). He consolidated the conquests of his predecessors, built numerous churches and monasteries, encouraged literature and art, centralized imperial authority by substituting regional warlords with administrative officials, and significantly expanded his hegemony over adjacent Islamic territories.[19][20][21]

The neighboring Muslim Adal Sultanate began to threaten the empire by repeatedly attempting to invade it, finally succeeding under Imam Mahfuz.[22] Mahfuz's ambush and defeat by Emperor Lebna Dengel brought about the early 16th-century jihad of the Ottoman-supported Adalite Imam Ahmed Gran, who was defeated in 1543 with the help of the Portuguese.[23] Greatly weakened, much of the Empire's southern territory and vassals were lost due to the Oromo migrations. In the north, in what is now Eritrea, Ethiopia managed to repulse Ottoman invasion attempts, although losing its access to the Red Sea to them.[24] Reacting to these challenges, in the 1630s Emperor Fasilides founded the new capital of Gondar, marking the start of a new golden age known as the Gondarine period. It saw relative peace, the successful integration of the Oromo and a flourishing of culture. With the deaths of Emperor Iyasu II (1755) and Iyoas I (1769) the realm eventually entered a period of decentralization, known as the Zemene Mesafint where regional warlords fought for power, with the emperor being a mere puppet.[25]

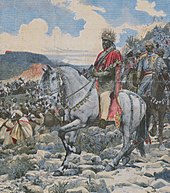

Emperor Tewodros II (r. 1855–1868) put an end to the Zemene Mesafint, reunified the Empire and led it into the modern period before dying during the British Expedition to Abyssinia. His successor Yohannes IV engaged primarily in war and successfully fought the Egyptians and Mahdists before dying against the latter in 1889. Emperor Menelik II, now residing in Addis Ababa, subjugated many peoples and kingdoms in what is now western, southern, and eastern Ethiopia, like Kaffa, Welayta, Harar, and other kingdoms. Thus, by 1898 Ethiopia expanded into its modern territorial boundaries. In the northern region, he confronted Italy's expansion. Through a resounding victory over the Italians at the Battle of Adwa in 1896, utilizing modern imported weaponry, Menelik ensured Ethiopia's independence and confined Italy to Eritrea.

Later, after the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, Benito Mussolini's Italian Empire occupied Ethiopia and established Italian East Africa, merging it with neighboring Eritrea and the Italian Somaliland colonies to the south-east. During World War II, the Italians were driven out of Ethiopia with the help of the British army. The Emperor returned from exile and the country became one of the founding members of the United Nations. However, the 1973 Wollo famine and domestic discontent led to the fall of the Empire in 1974 and the rise of the Derg.[26]

History

Background

After the fall of the Kingdom of Aksum in the 10th century AD, the Ethiopian Highlands would fall under the rule of the Zagwe Dynasty. The new rulers were Agaws that had come from the Lasta region, later ecclesiastical texts accused this dynasty of not having pure "Solomonic" stock and derided their achievements. Even at the zenith of their power, most Christians would consider them to be usurpers. However, the architecture of the Zagwe shows a connotation of earlier Aksumite traditions, among those can be seen in Lalibela, the building of rock hewn churches first appeared in the late Aksumite era and reached its peak under the Zagwe.[27]

The Zagwe were not able to stop squabbling over the throne, diverting men, energy and resources that could have been used to affirm the dynasty's authority. By the late 13th century, a young Amhara nobleman named Yekuno Amlak rose to power in Bete Amhara. He was strongly supported by the Orthodox Church as he promised to make the church a semi independent institution, he had also enjoyed support from the neighboring Muslim Makhzumi dynasty. Yekuno Amlak then rebelled against the Zagwe king and defeated him at the Battle of Ansata. Taddesse Tamrat argued that this king was Yetbarak, but due to a local form of damnatio memoriae, his name was removed from the official records.[28] A more recent chronicler of Wollo history, Getatchew Mekonnen Hasen, states that the last Zagwe king deposed by Yekuno Amlak was Na'akueto La'ab.[29][30]

Early Solomonic Period

Yekuno Amlak would rise to the throne by 1270 AD. He was allegedly a descendant of the last king of Aksum, Dil Na'od, and hence the royal kings of Aksum. Through the Aksumite royal lineage, it was also claimed that Yekuno Amlak was a descendant of the biblical king Solomon. The canonical form of the claim was set out in legends recorded in the Kebra Nagast, a 14th century text. According to this, the Queen of Sheba, who supposedly came from Aksum, visited Jerusalem where she conceived a son with King Solomon. On her return to her homeland of Ethiopia, she gave birth to the child, Menelik I. He and his descendants (which included the Aksumite royal house) ruled Ethiopia until overthrown by the Zagwe usurpers. Yekuno Amlak, as a supposed direct descendant of Menelik I, was therefore claimed to have "restored" the Solomonic line.[31]

Throughout Yekuno Amlak's reign he would enjoy friendly relations with the Muslims. He not only had established close ties with the neighboring Makhzumi dynasty but had also made contact with the Rasulids in Yemen and the Egyptian Mamluk Sultanate. In a letter sent to the Mamluke Sultan Baybars, he would state his intention of friendly cooperation with the Muslims of Arabia, and described himself as being a protector of all Muslims in Abyssinia. A devout Christian, he would order the construction of the church of Genneta Maryam, commemorating his work with an inscription that reads, "By the grace of God, I king Yekuno Amlak, after I had come to the throne by the will of God, built this church."[31][32]

In 1285 Yekuno Amlak was succeeded by his son Yagbe'u Seyon, who wrote a letter the Mamluke Sultan, Qalawun asking him to allow the patriarch of Alexandria to send an abuna or metropolitan for the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, but also protesting the Sultan's treatment of his Christian subjects in Egypt, stating that he was a protector of his own Muslim subjects in Ethiopia.[33] Towards the end of his reign, Yagbe'u refused to appoint one of his sons to be his successors and instead decreed that each of them should rule for one year, he was succeeded by his sons in 1294 but this agreement immediately broke down, by 1299 one of his sons Wedem Arad seized the throne. Wedem Arad seems to have been in conflict with the neighbouring Sultanate of Ifat who were trying to expand in eastern Shewa.[34]

Amda Seyon's Conquests

Wedem Arad was succeeded by his son, Amda Seyon I, whose reign witnessed the composition of a very detailed and seemingly accurate account of the monarch's various campaigns against his Muslim enemies. This was the first of a series of royal chronicles which were written for the Ethiopian Emperors until modern times. These royal chronicles provided an unbroken chronological record of the entire medieval period in the Horn of Africa. A no less important work produced during his reign was the Fetha Nagast or "Law of the Kings," which served as the country's legal code. Largely based on biblical principles, it codified the legal and social ideas of the time and remained in use until the early 20th century.[32]

The warlike emperor of Amda Seyon I conducted many campaigns in Gojjam, Damot and Eritrea, but his most important campaigns were against his Muslim enemies to the east, which shifted the balance of power in favour of the Christians for the next two centuries. Around 1320, Sultan an-Nasir Muhammad of the Mamluk Sultanate based in Cairo began persecuting Copts and destroying their churches. Amda Seyon then threatened to divert the flow of the Nile if the sultan did not stop his persecution. Haqq ad-Din I, sultan of Ifat, seized and imprisoned an Ethiopian envoy on his way back from Cairo. Amda Seyon responded by invading the Sultanate of Ifat, killing the sultan, sacking the capital and ravaging the Muslim territories, taking livestock, killing many inhabitants, destroying towns and mosques, and taking slaves.[35]

The Ifat sultan was succeeded by Sabr ad-Din I who rallied the Muslims and waged a rebellion against the Ethiopian occupation. Amda Seyon responded by launching another campaign against his Muslim adversaries to the east, killing the Sultan and campaigning as far as Adal, Dawaro and Bali in present day eastern Ethiopia. Amda Seyon's conquests significantly expanded the territory of the Ethiopian Empire, more than doubling it by size and establishing complete hegemony over the region. Relations between the Muslims of the Horn and the Ethiopian Empire seems to have broken down completely around this era, with the chronicler referring to the Muslims in the east and along the coast as "liars, hyenas, dogs, children of evil who deny the son of Christ."[36][37]

Golden age of Solomonic Rule

Following Amda Seyon's campaigns to the east. Most of the Muslims in the Horn would become tributaries to the Ethiopian Empire, among them being the Ifat Sultanate. Amda Seyon was succeeded by his son Newaya Krestos in 1344. Newaya Krestos would put down several Muslim revolts in Adal and Mora. Towards the end of his reign he aggressively helped the Patriarch of Alexandria Mark IV, who had been imprisoned by As-Salih Salih, the Sultan of Egypt. One step Newaya Krestos took was to imprison the Egyptian merchants in his kingdom, the Sultan was forced to back down.[38]

In 1382, Dawit I succeeded the son of Newaya Krestos, Newaya Maryam, as Emperor of Ethiopia. The tributary state of the Ifat Sultanate had begun to resist Ethiopian hegemony and assert their independence under Sultan Sa'ad ad-Din II. Sultan Sa'ad as-Din would then raid the Ethiopian frontier provinces capturing much loot and slaves, this resulted in Emperor Dawit I declaring all the Muslims of the surrounding region to be "enemies of the Lord" and invading the Ifat Sultanate, After a battle between Sa'ad ad-Din and the Emperor, in which the Ifat army was defeated and "no less than 400 elders, each of whom carried an iron bar as his insignia of office" were killed, Sa'ad ad-Din with his remaining supporters were chased to as far as Zeila on the coast of Somaliland. There, the Ethiopian army besieged Zeila, finally capturing the city and killing Sultan Sa'ad ad-Din, ending the Ifat Sultanate. After Sa'ad ad-Din's death "the strength of the Muslims was abated", as Egyptian historian al-Maqrizi states, and then the Amhara settled in the Muslim territories "and from the ravaged mosques and they made churches". The followers of Islam were said to have been harassed for over twenty years.[39] Following this victory, Ethiopian power would reach its zenith and this era would become legendary as a golden age of peace and stability for the Ethiopian Empire.[40]

However, the remaining Walashma returned from their exile in 1415 and established the Adal Sultanate centred around the Harar region. The Muslims then began to harass Christian held territories in the east prompting Emperor Yeshaq I to dedicate much of his time to defending his eastern peripheral territories, he seems to have employed several Egyptian Christian advisors to drill his army and teach them how to make Greek fire. These advances were not enough to keep the Muslims at bay and Emperor Yeshaq was soon killed fighting the Adalites in 1429. Yeshaq's death was followed by several years of dynastic confusion during which 5 emperors succeeded each other in 5 years. However in 1434, Zara Yaqob of Ethiopia would establish himself on the throne.[41]

During his first years on the throne, Zara Yaqob launched a strong campaign against survivals of pagan worship and "un-Christian practices" within the church. He also took measures to greatly centralize the administration of the country, bringing regions under much tighter imperial control. After hearing about the demolition of the Egyptian Debre Mitmaq monastery, he ordered a period of national mourning and built a church of the same name in Tegulet. He then sent envoys to Egyptian Sultan, Sayf ad-Din Jaqmaq strongly protesting against the persecution of Egyptian Copts and threaten to divert the flow of the Nile. The Sultan would then encourage the Adal Sultanate to invade the province of Dawaro to distract the Emperor, however this invasion was repulsed by the Emperor at the Battle of Gomit. The Egyptian sultan then had the Patraich of Alexandria severely beaten and threaten to execute him, Emperor Zara Yaqob decided to back down and did not move in to Adal territory. Zara Yaqob persecuted many idolaters who admitted to worshipping pagan gods, these idolators were decapitated in public. Zara Yaqob later founded Debre Berhan after seeing a miraculous light that in the sky. Believing this was a sign from God showing his approval for his persecution of pagans, the emperor ordered a church built on the site, and later constructed an extensive palace nearby, and a second church, dedicated to Saint Cyriacus.[38][42]

Zara Yaqob was succeeded by Baeda Maryam I. Emperor Baeda Maryam would give the title of the Queen Mother to Eleni of Ethiopia, one of his father's wives. She was proved to be an effective member of the royal family, and Paul B. Henze comments that she "was practically co-monarch" during his reign. After the death of Baeda Maryam in 1478 he was succeeded by his 7 year old son Eskender, to whom Eleni would serve as his regent. She would attempt to establish peace with the Adal Sultan Muhammad, but could not prevent the Emir of Harar, Mahfuz from making raids into Ethiopian territory. When Eskender was of age, he invaded Adal and sacked its capital, Dakkar but was killed in an ambush returning home. His successor, Emperor Na'od was eventually killed defending Ethiopian territory from Adalite raids. In 1517 Mahfuz invaded the Ethiopian province of Fatager, but was killed and ambushed by Emperor Dawit II (Lebna Dengel). His chronicles state that the Muslim threat was finished and the Emperor return to the highlands as a hero.[43]

Adal Sultanate Invasion

In 1527 a young imam by the name of Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi would rise to power in Adal after years of internal strife. The Adal Sultanate would stockpile on imported firearms, cannons and other advanced weaponry from Arabia and the Ottoman Empire. He invaded Ethiopia in 1529 and inflicted a heavy defeat on Emperor Dawit II, but later withdrew. He returned two years later to begin a definite invasion of the empire, burning churches, forcibly converting Christians and massacring the inhabitants. According to the chroniclers everywhere he went his men "slew every adult Christian they found, and carried off the youths and the maidens and sold them as slaves." By the mid 1530s most of Ethiopia was under Adalite occupation and Lebna Dengel fled from mountain fortress to mountain fortress until he finally died of natural causes in Debre Damo.[44][45]

The Emperor was succeeded by his 18 year old son, Gelawdewos, who faced a desperate situation but rallied his soldiers and people to resist the Muslim invasion. By 1540 Gelawdewos led a small force of around 70 men resisting in the highlands of Shewa. However, in 1541 four hundred well armed Portuguese musketeers had arrived in Massawa where they were reinforced by small contingents of Ethiopian warriors, this modest force made their way across Tigray where they would defeat much larger contingents of Adalite men. Alarmed by the success of the Portuguese, Gragn would send a petition to the Ottoman Empire and would receive 2,900 musket armed reinforcements. Together with his Turkish allies Gragn would attack the Portuguese camp at Wofla killing 200 of their rank and file including their commander, Cristóvão da Gama.[46]

After the catastrophe at Wofla, the surviving Portuguese were able to meet up with Gelawdewos and his army in the Semien Mountains. The Emperor did not hesitate to take the offensive and won a major victory at the Battle of Wayna Daga when the fate of Abyssinia was decided by the death of the Imam and the flight of his army. The invasion force collapsed and all the Abyssinians who had been cowed by the invaders returned to their former allegiance, the reconquest of Christian territories proceeded without encountering any effective opposition.[47]

In 1559 Gelawdewos was killed attempting to invade Adal Sultanate at the Battle of Fatagar, and his severed head was paraded in Adal's capital Harar.[48]

Early modern period

The Ottoman Empire occupied parts of Ethiopia, from 1557, establishing Habesh Eyalet, the province of Abyssinia, by conquering Massawa, the Empire's main port and seizing Suakin from the allied Funj Sultanate in what is now Sudan. In 1573 the Adal Sultanate attempted to invade Ethiopia again however Sarsa Dengel successfully defended the Ethiopian frontier at the Battle of Webi River.[49]

The Ottomans were checked by Emperor Sarsa Dengel's victory and sacking of Arqiqo in 1589, thus containing them on a narrow coastline strip. The Afar Sultanate maintained the remaining Ethiopian port on the Red Sea, at Baylul.[50] Oromo migrations through the same period, occurred with the movement of a large pastoral population from the southeastern provinces of the Empire. A contemporary account was recorded by the monk Abba Bahrey, from the Gamo region. Subsequently, the empire organization changed progressively, with faraway provinces taking more independence. A remote province such as Bale is last recorded paying tribute to the imperial throne during Yaqob reign (1590–1607).[51]

In 1636, Emperor Fasilides founded Gondar as a permanent capital, which became a highly stable, prosperous commercial center. This period saw profound achievements in Ethiopian art, architecture, and innovations such as the construction of the royal complex Fasil Ghebbi, and 44 churches[52] that were established around Lake Tana. In the arts, the Gondarine period saw the creation of diptychs and triptychs, murals and illuminated manuscripts, mostly with religious motifs. The reign of Iyasu the Great (1682-1706) was a major period of consolidation. It also saw the dispatching of embassies to Louis XIV's France and to Dutch India. The Early Modern period was one of intense cultural and artistic creation. Notable philosophers from that area are Zera Yacob and Walda Heywat. After the death of Iyasu I the empire fell into a period of political turmoil.

Modern era

From 1769 to 1855, the Ethiopian empire passed through a period known as the Princes Era (in Amharic: Zemene Mesafint). This was a period of Ethiopian history with numerous conflicts between the various Ras (equivalent to the English dukes) and the Emperor, who had only limited power and only dominated the area around the contemporary capital of Gondar. Both the development of society and culture stagnated in this period. Religious conflict, both within the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and between them and the Muslims were often used as a pretext for mutual strife. The Princes Era ended with the reign of Emperor Tewodros II.

In 1868, following the imprisonment of several missionaries and representatives of the British government, the British engaged in the punitive Expedition to Abyssinia against Emperor Tewodros. With the backing of most nobles in Ethiopia, the campaign was a success for Britain and the Ethiopian Emperor committed suicide rather than surrender.

From 1874 to 1876, the Empire expanded into Eritrea, under Yohannes IV King of Tembien, whose forces led by Ras Alula won the Ethiopian-Egyptian War, decisively beating the Egyptian forces at the Battle of Gundet, in Hamasien. In 1887 Menelik king of Shewa invaded the Emirate of Harar after his victory at the Battle of Chelenqo.[53] In 1889 Menelik's general Gobana Dacche also defeated the Hadiya leader Hassan Enjamo and annexed Hadiya territory.[54]

The 1880s were marked by the Scramble for Africa. Italy, seeking a colonial presence in Africa, was awarded Eritrea by Britain which led to the Italo-Ethiopian War of 1887–1889 and the scramble for Eritrea's coastal regions between King Yohannes IV of Tembien and Italy. After the death of Emperor Yohannes IV, Italy signed a treaty with Shewa (an autonomous kingdom within the empire), creating the protectorate of Abyssinia.

Due to significant differences between the Italian and Amharic translations of the treaty, Italy believed they had subsumed Ethiopia as a protectorate, while Menelik II of Shewa repudiated the protectorate status in 1893. Insulted, Italy declared war on Ethiopia in 1895. The First Italo-Ethiopian War resulted in the 1896 Battle of Adwa, in which Italy was decisively defeated by the numerically superior Ethiopians. As a result, the Treaty of Addis Ababa was signed in October, which strictly delineated the borders of Eritrea and forced Italy to recognize the independence of Ethiopia. Due to the Entoto Reforms, which provided the Ethiopian Military with modern rifles, many Italian Commanders expressed shock when seeing that some Ethiopians had more advanced rifles than the average Italian Infantryman.

Beginning in the 1890s, under the reign of the Emperor Menelik II, the empire's forces set off from the central province of Shewa to incorporate through conquest inhabited lands to the west, east and south of its realm.[55] The territories that were annexed included those of the western Oromo (non-Shoan Oromo), Sidama, Gurage, Wolayta,[56] and Dizi.[57] Among the imperial troops was Ras Gobena's Shewan Oromo militia. Many of the lands that they annexed had never been under the empire's rule, with the newly incorporated territories resulting in the modern borders of Ethiopia.[58]

Delegations from the United Kingdom and France – European powers whose colonial possessions lay next to Ethiopia – soon arrived in the Ethiopian capital to negotiate their own treaties with this newly-proven power.

Italian invasion and World War II

In 1935, Italian soldiers under the command of Marshal Emilio De Bono began what is known as the Second Italo-Ethiopian War. During the conflict, both Ethiopian and Italian troops committed war crimes. Ethiopian troops are known to have made use of Dum-Dum bullets (in violation of the Hague Conventions) and mutilated captured soldiers (often with castration).[59] Italian troops used sulfur mustard in chemical warfare, ignoring the Geneva Protocol that it had signed seven years earlier. The Italian military dropped mustard gas in bombs, sprayed it from airplanes and spread it in powdered form on the ground. 150,000 chemical casualties were reported, mostly from mustard gas.

On May 1, 1936, Haile Selassie took a train to Djibouti and then boarded a British ship to Jerusalem,[60] spending the majority of his time in the city with Ethiopian monks, praying with them at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.[61][62] He then fled to Bath, where he was granted asylum by British authorities who did not want to stay in London as long as possible due to being perceived as "politically embarrassing". Upon arrival, he stayed at a hotel, purchasing Fairfield House shortly afterward to spend the remainder of his time.[63] He was accompanied by his children, grandchildren, servants and others. In Bath, Haile Selassie accustomed to the "army of servants" and living in single house as financially restricted. He was seen getting rid of jewelry on a couple of occasions. Upon leaving England, he left the house for the elderly, not visiting again until 1954.[64]

The war lasted seven months, during which Addis Ababa was occupied on May 5, 1936, before an Italian victory was declared on May 9, 1936. Italy proclaimed the establishment of he Italian Empire in East Africa, with King Victor Emmanuel III as Emperor of Ethiopia, which was united with other Italian colonies in eastern Africa to form the new colony of Italian East Africa on June 1. The invasion was condemned by the League of Nations, though not much was done to end the hostility.

On June 30, 1936, Selassie traveled once to Geneva to plead with the League of Nations that Ethiopia not be officially recognized as part of Italian Empire. He also had European allies who traveled to Ethiopia to report the news about the Ethiopian Army struggling with Italy. This helped the British's later entry into Ethiopia.[64][65][66]

On 10 June 1940, Italy declared war on the United Kingdom and France, as the latter was in the process of being conquered by German forces at the time and Benito Mussolini wished to expand Italy's colonial holdings. The Italian conquest of British Somaliland in August 1940 was successful, but the war turned against Italy afterward. The British accompanied Haile Selassie to Sudan and helped him organise his army within seven months,[67] finally launching a military campaign in January 1941 which returned him to the throne on May 5 of the same year.[64][68][69]

Post War Ethiopia

On 27 August 1942, Haile Selassie abolished the legal basis of slavery throughout the empire and imposed severe penalties, including death, for slave trading.[70] After World War II, Ethiopia became a charter member of the United Nations. In 1948, the Ogaden, a region disputed with Somalia, was granted to Ethiopia.[71] On 2 December 1950, the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 390 (V), establishing the federation of Eritrea (the former Italian colony) into Ethiopia.[72] Eritrea was to have its own constitution, which would provide for ethnic, linguistic, and cultural balance, while Ethiopia was to manage its finances, defense, and foreign policy.[72]

Despite his centralization policies that had been made before World War II, Haile Selassie still found himself unable to push for all the programs he wanted. In 1942, he attempted to institute a progressive tax scheme, but this failed due to opposition from the nobility, and only a flat tax was passed; in 1951, he agreed to reduce this as well.[73] Ethiopia was still "semi-feudal",[74] and the emperor's attempts to alter its social and economic form by reforming its modes of taxation met with resistance from the nobility and clergy, which were eager to resume their privileges in the postwar era.[73] Where Haile Selassie actually did succeed in effecting new land taxes, the burdens were often passed by the landowners to the peasants.[73] Despite his wishes, the tax burden remained primarily on the peasants.

Between 1941 and 1959, Haile Selassie worked to establish the autocephaly of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.[75] The Ethiopian Orthodox Church had been headed by the abuna, a bishop who answered to the Patriarchate in Egypt. Haile Selassie applied to Egypt's Holy Synod in 1942 and 1945 to establish the independence of Ethiopian bishops, and when his appeals were denied he threatened to sever relations with the See of St. Mark.[75] Finally, in 1959, Pope Kyrillos VI elevated the Abuna to Patriarch-Catholicos.[75] The Ethiopian Church remained affiliated with the Alexandrian Church.[73] In addition to these efforts, Haile Selassie changed the Ethiopian church-state relationship by introducing taxation of church lands, and by restricting the legal privileges of the clergy, who had formerly been tried in their own courts for civil offenses.[73][76]

During the celebrations of his Silver Jubilee in November 1955, Haile Selassie introduced a revised constitution,[77] whereby he retained effective power, while extending political participation to the people by allowing the lower house of parliament to become an elected body. Party politics were not provided for. Modern educational methods were more widely spread throughout the Empire, and the country embarked on a development scheme and plans for modernization, tempered by Ethiopian traditions, and within the framework of the ancient monarchical structure of the state. Haile Selassie compromised when practical with the traditionalists in the nobility and church. He also tried to improve relations between the state and ethnic groups, and granted autonomy to Afar lands that were difficult to control. Still, his reforms to end feudalism were slow and weakened by the compromises he made with the entrenched aristocracy. The Revised Constitution of 1955 has been criticized for reasserting "the indisputable power of the monarch" and maintaining the relative powerlessness of the peasants.[78]

On 13 December 1960, while Haile Selassie was on a state visit to Brazil, his Imperial Guard forces staged an unsuccessful coup, briefly proclaiming Haile Selassie's eldest son Asfa Wossen as emperor. The coup d'état was crushed by the regular army and police forces. The coup attempt lacked broad popular support, was denounced by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, and was unpopular with the army, air force and police. Nonetheless, the effort to depose the emperor had support among students and the educated classes.[79] The coup attempt has been characterized as a pivotal moment in Ethiopian history, the point at which Ethiopians "for the first time questioned the power of the king to rule without the people's consent".[80] Student populations began to empathize with the peasantry and poor, and to advocate on their behalf.[80] The coup spurred Haile Selassie to accelerate reform, which was manifested in the form of land grants to military and police officials.

The emperor continued to be a staunch ally of the West, while pursuing a firm policy of decolonization in Africa, which was still largely under European colonial rule. The United Nations conducted a lengthy inquiry regarding the status of Eritrea, with the superpowers each vying for a stake in the state's future. Britain, the administrator at the time, suggested the partition of Eritrea between Sudan and Ethiopia, separating Christians and Muslims. A UN plebiscite voted 46 to 10 to have Eritrea be federated with Ethiopia, which was later stipulated on 2 December 1950 in resolution 390 (V). Eritrea would have its own parliament and administration and would be represented in what had been the Ethiopian parliament and would become the federal parliament.[81] However, Haile Selassie would have none of European attempts to draft a separate Constitution under which Eritrea would be governed, and wanted his own 1955 Constitution to apply in both Ethiopia and Eritrea. In 1961, tensions between independence-minded Eritreans and Ethiopian forces culminated in the Eritrean War of Independence. The emperor declared Eritrea the fourteenth province of Ethiopia in 1962.[82]

In 1963, Haile Selassie presided over the formation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), the precursor of the continent-wide African Union (AU). The new organization would establish its headquarters in Addis Ababa. In May of that year, Haile Selassie was elected as the OAU's first official chairperson, a rotating seat. Along with Modibo Keïta of Mali, the Ethiopian leader would later help successfully negotiate the Bamako Accords, which brought an end to the border conflict between Morocco and Algeria. In 1964, Haile Selassie would initiate the concept of the United States of Africa, a proposition later taken up by Muammar Gaddafi.[83]

Student unrest became a regular feature of Ethiopian life in the 1960s and 1970s. Marxism took root in large segments of the Ethiopian intelligentsia, particularly among those who had studied abroad and had thus been exposed to radical and left-wing sentiments that were becoming popular in other parts of the globe.[79] Resistance by conservative elements at the Imperial Court and Parliament, and by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, made Haile Selassie's land reform proposals difficult to implement, and also damaged the standing of the government, costing Haile Selassie much of the goodwill he had once enjoyed. This bred resentment among the peasant population. Efforts to weaken unions also hurt his image. As these issues began to pile up, Haile Selassie left much of domestic governance to his Prime Minister, Aklilu Habte Wold, and concentrated more on foreign affairs.

Fall of monarchy

The government's failure to adequately respond to the 1973 Wollo famine, the growing discontent of urban interest groups, and high fuel prices due to the 1973 oil crisis led to a revolt in February 1974 by the army and civilian populace. In June, a group of military officers formed the Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces, Police, and Territorial Army also known as the Derg to maintain law and order due to the powerlessness of the civilian government following the widespread mutiny.

In July, Emperor Haile Selassie gave the Derg key concessions to arrest military and government officials at every level. Soon both former Prime Ministers Tsehafi Taezaz Aklilu Habte-Wold and Endelkachew Makonnen, along with most of their cabinets, most regional governors, many senior military officers and officials of the Imperial court were imprisoned. In August, after a proposed constitution creating a constitutional monarchy was presented to the Emperor, the Derg began a program of dismantling the imperial government to forestall further developments in that direction. The Derg deposed and imprisoned the Emperor on 12 September 1974 and chose Lieutenant General Aman Andom, a popular military leader and a Sandhurst graduate, to be acting head of state. This was pending the return of Crown Prince Asfaw Wossen from medical treatment in Europe when he would assume the throne as a constitutional monarch. However, General Aman Andom quarrelled with the radical elements in the Derg over the issue of a new military offensive in Eritrea and their proposal to execute the high officials of Selassie's former government. After eliminating units loyal to him: the Engineers, the Imperial Bodyguard and the Air Force, the Derg removed General Aman from power and executed him on 23 November 1974, along with some of his supporters and 60 officials of the previous Imperial government.[84]

Brigadier General Tafari Benti became the new chairman of the Derg and the head of state. The monarchy was formally abolished in March 1975, and Marxism-Leninism was proclaimed the new ideology of the state. Emperor Haile Selassie died under mysterious circumstances on 27 August 1975 while his personal physician was absent. It is commonly believed that Mengistu Haile Mariam killed him, either by ordering it done or by his own hand although the former is more likely.[85]

Society

According to Bahrey,[86] there were ten social groups in the feudal Ethiopia of his time, i.e. at the end of the 16th century. These social groups consisted of the monks; the debtera; lay officials (including judges); men at arms giving personal protection to the wives of dignitaries and to princesses; the shimaglle, who were the lords and hereditary landowners; their farm labourers or serfs; traders; artisans; wandering singers; and the soldiers, who were called chewa. According to modern thinking, some of these categories are not true classes. But at least the shimaglle, the serfs, the chewa, the artisans and the traders constitute definite classes. Power was vested in the Emperor and those aristocrats he appointed to execute his power, and the power enforcing instrument consisted of a class of soldiers, the chewa.[87]

Military

From the reign of Amde Tseyon, Chewa regiments, or legions, formed the backbone of the Empire military forces. The Ge'ez term for these regiments is ṣewa (ጼዋ) while the Amharic term is č̣äwa (ጨዋ). The normal size of a regiment was several thousand men.[88] Each regiment was allocated a fief (Gult), to ensure its upkeep ensured by the land revenue.[89]

In 1445, following the Battle of Gomit, the chronicles record that Emperor Zara Yaqob started garrisoning the provinces with Chewa regiments.

| Name of regiment[90] | Region | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Bäṣär waǧät | Serae, Dawaro, Menz, Gamo | Enemy of the waǧät |

| Ǧan amora | Dobe'a, Tselemt, Gedem | Eagle of the majesty |

| Ǧan sagana | Dawaro, Dobe'a, Angot | |

| č̣äwa Bale | Bali | |

| č̣äwa Maya | Medre Bahr | |

| Bäṣur amora | Gamo | Spear of the eagle |

| Bäṣär šotäl | Damot | Spear of the foe |

| č̣äwa Begemder | Begemder | |

| č̣äwa Ifat | Ifat |

Major divisions of the military were :

- Regiments at the court, under high court officials

- Regiments in the provinces, under regional Rases or other officials

- Regiments in border regions, or more autonomous provinces, such as Hadiya, Bahir Negash, Bale, under azmač who were military officials appointed by the king.[91]

One of the Chewa regiments, known as the Abe Lahm in Geez, or the Weregenu, in Oromo, lasted, and participated to the Battle of Adwa, only to be phased out in the 1920s.[92]

The modern army was created under Ras Tafari Makonnen, in 1917, with the formation of the Kebur Zabagna, the imperial guard.

Economy

The economy consisted of centuries old barter system with "primitive money" and currency of various kinds until the 20th century in the framework of feudal system.[93][94] Peasants worked to produce and fixated their activities to taxation, marketing infrastructure and agrarian production.[95][96]

In 1905, Menelik II established the first bank, Bank of Abyssinia following concession from British occupied National Bank of Egypt in December 1904, that used to monopolize all government public funds, loans, print banknotes, mint coins and other privileges.[97] It expanded branches to Harar, Dire Dawa, Gore and Dembidolo and agencies in Gambela and transit office in Djibouti.[98] In 1932, it was renamed as "Bank of Ethiopia" following paid compensation by Emperor Haile Selassie. To promote industrial and manufacturing expansion, Haile Selassie, with assistance of National Economic Council, embarked development plan encompassing three Five-Years Master Plan from 1957 to 1974.[99][100][101] Between 1960 and 1970, Ethiopia enjoyed an annual 4.4% growth rate in per capita and gross domestic product (GDP). There was an increase of manufacturing growth rate from 1.9% in 1960/61 to 4.4% in 1973/74, with wholesale, retail trade, transportation, and communication sectors increased from 9.5% to 15.6%.[102] Ethiopia exported around 800,000 bushels of wheat, mainly to the Kingdom of Egypt, The Dutch East Indies, and Greece. The GDP of Ethiopia around 1934 was $1.3 billion, before dropping drastically due to the Second Italo-Ethiopian War.

Currency

The most common currency of the earlier periods of Ethiopian history were essential items such as, "amole" (salt bars), pieces of cloth or iron and later cartridges. It's only in the 19th century that the Maria Theresa Thaler had become the medium of exchange for large transactions until Menelik finally started minting local currency around the turn of the century.[103]

Government

As feudalism became the central tenet in the Ethiopian Empire, it developed into an authoritarian system with institutionalized social inequality. As land became the prime commodity, its acquisition became the main driving force behind imperialism, especially from the reign of Menelik II onwards.[104]

As part of Emperor Haile Selassie's modernization efforts, the traditional monarchical regime was reformed through the introduction of the 1931 and 1955 constitutions, which introduced a unitary parliamentary system with two legislative bodies: the Chamber of Senate (Yeheggue Mewossegna Meker Beth) and Chamber of Deputies (Yeheggue Memeriya Meker Beth).[105][106] Under the 1956 constitution Article 56, no one can be simultaneously a member of both chambers, who meet at the beginning or ending of each session.[107]

In the parliamentary structure, the Chamber of Deputies consisted of 250 members elected every four years, whereas the Senate consisted of one-half of the Deputies (125) and were appointed by the Emperor in every six years.[108]

See also

| History of Ethiopia |

|---|

|

| History of Eritrea |

|---|

|

| |

- History of Ethiopia

- Ethiopian historiography

- Emperor of Ethiopia

- Crown Council of Ethiopia

- Army of the Ethiopian Empire

- Sultanate of Ifat

- Sultanate of Shewa

- Zemene Mesafint (1755–1855)

- First Italo-Ethiopian War (1895–1896)

- Second Italo-Ethiopian War (1935–1936)

- Italian East Africa (1936–1941)

- Arbegnoch (1936–1941)

- East African campaign (World War II) (1941)

- Italian guerrilla war in Ethiopia (1941–1943)

- Ethiopian Revolution (1974)

- Ethiopian Civil War (1974–1991)

Notes

References

- ^ The old tradition of the Ethiopian emperors was travelling around the country accompanied by their many courtiers and innumerable soldiers, living off the produce of peasants, and dwelling in fortified encampments known as katamas. These katamas would serve as the headquarters of the empire.[1] Despite this several Ethiopian rulers had attempted to establish fixed capitals such as Tegulet, Emfraz and Debre Birhan.[2]

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1982). History Of Ethiopian Towns. Steiner. p. 41. ISBN 978-3-515-03204-9.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (2009). "Barara, the Royal City of 15th and Early 16th Century (Ethiopia). Medieval and Other Early Settlements Between Wechecha Range and Mt Yerer". Annales d'Éthiopie. 24 (1): 209–249. doi:10.3406/ethio.2009.1394.

- ^ The Southern Marches of Imperial Ethiopia: Essays in History and Social Anthropology, Donham Donald Donham, Wendy James, Christopher Clapham, Patrick Manning. CUP Archive, Sep 4, 1986, p. 11, https://books.google.com/books?id=dvk8AAAAIAAJ&q=Lisane+amharic#v=snippet&q=Lisane%20amharic&f=false Archived 28 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia, Paul B. Henze, November 18, 2008, p. 78, https://books.google.com/books?id=3VYBDgAAQBAJ&q=Lisane#v=snippet&q=Lisane&f=false Archived 28 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Nathaniel T. Kenney (1965). "Ethiopian Adventure". National Geographic. 127: 555.

- ^ Negash, Tekeste (2006). "The Zagwe Period and the Zenith of Urban Culture in Ethiopia, Ca. 930–1270 AD". Africa: Rivista Trimestrale di Studi e Documentazione dell'Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente. 61 (1): 120–137. JSTOR 40761842.

- ^ Constitution of Ethiopia, 4 November 1955, Article 76 (source: Constitutions of Nations: Volume I, Africa by Amos Jenkins Peaslee)

- ^ "Ethiopia Ends 3,000 Year Monarchy". Milwaukee Sentinel. 22 March 1975. p. 3.

- ^ "Ethiopia ends old monarchy". The Day. 22 March 1975. p. 7.

- ^ Henc van Maarseveen; Ger van der Tang (1978). Written Constitutions: A Computerized Comparative Study. Brill. p. 47.

- ^ "Ethiopia". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 1987.

- ^ a b The Royal Chronicle of his reign is translated in part by Richard K. P. Pankhurst, The Ethiopian Royal Chronicles (Addis Ababa: Oxford University Press, 1967).

- ^ Markessini, Joan (2012). Around the World of Orthodox Christianity – Five Hundred Million Strong: The Unifying Aesthetic Beauty. Dorrance Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4349-1486-6.

- ^ Morgan, Giles (2017). St George: The patron saint of England. Oldcastle Books. ISBN 978-1-84344-967-6.

- ^ E. A. Wallis Budge (2014). A History of Ethiopia. Vol. I: Nubia and Abyssinia. Routledge. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-317-64915-1.

- ^ Lewis, William H. (1956). "The Ethiopian Empire: Progress and Problems". Middle East Journal. 10 (3): 257–268. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4322824.

- ^ Hathaway, Jane (2018). The Chief Eunuch of the Ottoman Harem: From African Slave to Power-Broker. Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-107-10829-5.

- ^ Barsbay. Encyclopedia Aethiopica.

- ^ Erlikh, Hagai (2000). The Nile Histories, Cultures, Myths. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-55587-672-2.

- ^ Hassen, Mohammed. Oromo of Ethiopia with special emphasis on the Gibe region (PDF). University of London. p. 22.

- ^ J. Spencer Trimingham, Islam in Ethiopia (Oxford: Geoffrey Cumberlege for the University Press, 1952), p. 75

- ^ The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 3. Cambridge University Press. 1975. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-521-20981-6.

- ^ "Adal". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Pankhurst, History, p. 70; Özbaran, 87

- ^ Pankhurst, History, p. 119

- ^ Salvano, Tadese Tele (2018). የደረግ አነሳስና (የኤርትራና ትግራይ እንቆቅልሽ ጦርነት) [The Derg Initiative (The Eritrean-Tigray Mysterious War)]. Tadese Tele Salvano. pp. 81–97. ISBN 978-0-7915-9662-3.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (2001). The Ethiopians: A History. Wiley. p. 45. ISBN 0-631-22493-9.

- ^ Taddesse Tamrat, Church and State in Ethiopia (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), p. 68 n.1 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Getachew Mekonnen Hasen, Wollo, Yager Dibab (Addis Ababa: Nigd Matemiya Bet, 1992), pp. 28–29 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (2001). The Ethiopians: A History. Wiley. p. 46. ISBN 0-631-22493-9.

- ^ a b Henze, Paul B. (2000). Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia. Hurst & Company. p. 58. ISBN 1-85065-393-3.

- ^ a b Pankhurst, Richard (2001). The Ethiopians: A History. Wiley. p. 57. ISBN 0-631-22493-9.

- ^ Cited in Henry Yule, The Travels Of Marco Polo (London, 1871), in his notes to Book 3, Chapter 35.

- ^ Henze, Paul B. (2000). Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia. Hurst & Company. p. 59. ISBN 1-85065-393-3.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1997). The Ethiopian Borderlands Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century. Red Sea Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-932415-19-6.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1997). The Ethiopian Borderlands Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century. Red Sea Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-932415-19-6.

- ^ Erlikh, Ḥagai (2002). The Cross and the River Ethiopia, Egypt, and the Nile. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-55587-970-9.

- ^ a b Henze, Paul B. (2000). Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia. Hurst & Company. p. 67. ISBN 1-85065-393-3.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1982). History Of Ethiopian Towns. Steiner. p. 58. ISBN 978-3-515-03204-9.

- ^ Henze, Paul B. (2000). Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia. Hurst & Company. p. 68. ISBN 1-85065-393-3.

- ^ Mordechai, Abir. Ethiopia And The Red Sea (PDF). Hebrew University of Jerusalem. pp. 26–27.

- ^ A. Wallace Budge, E. (1828). History Of Ethiopia Nubia And Abyssinia. Vol. 1. Methuen & co. p. 300.

- ^ Henze, Paul B. (2000). Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia. Hurst & Company. p. 75. ISBN 1-85065-393-3.

- ^ Trimmingham, John Spencer (1952). Islam in Ethiopia. Frank Cass & Company. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-7146-1731-2.

- ^ Cerulli, Enrico. Islam Yesterday and Today translated by Emran Waber. pp. 376–381.

- ^ Trimmingham, John Spencer (1952). Islam in Ethiopia. Frank Cass & Company. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-7146-1731-2.

- ^ Trimmingham, John Spencer (1952). Islam in Ethiopia. Frank Cass & Company. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-7146-1731-2.

- ^ Akyeampong, Emmanuel (2 February 2012). Dictionary of African Biography. Vol. 1–6. OUP USA. p. 451. ISBN 978-0-19-538207-5.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1997). The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century. The Red Sea Press. p. 375. ISBN 978-0-932415-19-6.

- ^ Richard Pankhurst, The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to The End of the 18th Century Asmara. Red Sea Press, Inc., 1997. p. 390 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Braukämper, Islamic History and Culture in Southern Ethiopia: Collected Essays (Hamburg: Lit Verlag, 2002), p. 82

- ^ "Gonder". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Caulk, Richard (1971). "The Occupation of Harar: January 1887". Journal of Ethiopian Studies. 9 (2): 1–20. JSTOR 41967469.

- ^ Zewde, Bahru (25 March 2024). Society, State, and History Selected Essays. Addis Ababa University Printing Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-99944-52-15-6.

- ^ John Young (1998). "Regionalism and Democracy in Ethiopia". Third World Quarterly. 19 (2): 192. doi:10.1080/01436599814415. JSTOR 3993156.

- ^ International Crisis Group, "Ethnic Federalism and its Discontents". Issue 153 of ICG Africa report (4 September 2009) p. 2.

- ^ Haberland, Eike (1983). "An Amharic Manuscript on the Mythical History of the Adi kyaz (Dizi, South-West Ethiopia)". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 46 (2): 240. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00078836. S2CID 162587450. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ Edward C. Keefer (1973). "Great Britain and Ethiopia 1897–1910: Competition for Empire". International Journal of African Studies. 6 (3): 470. doi:10.2307/216612. JSTOR 216612.

- ^ Antonicelli 1975, p. 79.

- ^ The New International Year Book. Dodd, Mead and Company. 1941.

- ^ "The Lion of Judah and Jerusalem". embassies.gov.il. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ Bowers, Keith (2016). Imperial Exile: Emperor Haile Selassie in Britain 1936-1940. TSEHAI Publishers & Distributors. ISBN 978-1-59907-168-8.

- ^ "Members of Ethiopian Diaspora Gather at British Home of Former Emperor". VOA. 14 January 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

:1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "(1936) Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, "Appeal to the League of Nations"". 20 May 2008. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (2002). "Emperor Haile Sellassie's Arrival in Britain: An Alternative Autobiographical Draft by Percy Arnold". Northeast African Studies. 9 (2): 1–46. doi:10.1353/nas.2007.0008. ISSN 0740-9133. JSTOR 41931306. S2CID 144707809.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1996). "Emperor Haile Sellassie's Autobiography, and an Unpublished Draft". Northeast African Studies. 3 (3): 69–109. doi:10.1353/nas.1996.0015. ISSN 0740-9133. JSTOR 41931150. S2CID 143268411.

- ^ "Emperor Haile Selassie I Returns Triumphant to Ethiopia". Origins. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ "Haile Selassie, last emperor of Ethiopia and architect of modern Africa". HistoryExtra. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ Peter P. Hinks, John R. McKivigan, R. Owen Williams (2007). Encyclopedia of antislavery and abolition, Greenwood Publishing Group, p.248. ISBN 0-313-33143-X.

- ^ Shinn, David Hamilton and Ofcansky, Thomas P. Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia. 2004, page 201.

- ^ a b Shinn, David Hamilton and Ofcansky, Thomas P. Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia. 2004, page 140-1.

- ^ a b c d e Ofcansky, Thomas P., and Berry, Laverle. Ethiopia: A Country Study. 2004, page 63-4.

- ^ Willcox Seidman, Ann. Apartheid, Militarism, and the U.S. Southeast. 1990, page 78.

- ^ a b c Watson, John H. Among the Copts. 2000, page 56.

- ^ Nathaniel, Ras. 50th Anniversary of His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I. 2004, page 30.

- ^ "Ethiopia Administrative Change and the 1955 Constitution". Country-studies.com. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- ^ "Ethiopia's Revised Constitution". Middle East Journal. 10 (2): 194–199. 1956. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4322802.

- ^ a b Bahru Zewde, A History of Modern Ethiopia, second edition (Oxford: James Currey, 2001), pp.220–26

- ^ a b Mammo, Tirfe. The Paradox of Africa's Poverty: The Role of Indigenous Knowledge. 1999, page 100.

- ^ "General Assembly Resolutions 5th Session". United Nations. Retrieved 16 October 2007.

- ^ Semere Haile "The Origins and Demise of the Ethiopia-Eritrea Federation", Issue: A Journal of Opinion, 15 (1987), pp.9–17

- ^ "Ethiopia: New African Union Building and Kwame Statue (Video)". Archived from the original on 15 June 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ "Ethiopia Executes 60 Former Officials, Including 2 Premiers and Military Chief". The New York Times. 24 November 1974. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ Bulcha, Mekuria (1997). "The Politics of Linguistic Homogenization in Ethiopia and the Conflict over the Status of "Afaan Oromoo"". African Affairs. 96 (384): 325–352. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a007852. ISSN 0001-9909. JSTOR 723182.

- ^ Bahrey. (1954). History of the Galla. In C.F. Beckingham and G.B.W. Huntingford

- ^ Transitional government of Ethiopia, National Conservation Strategy, 1994, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/720181468749078939/pdf/multi-page.pdf Archived 28 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mordechai ABIR, Ethiopia and the Red Sea, p. 51 https://books.google.com/books?id=7fArBgAAQBAJ&dq=chewa%20ehiopia&pg=PA49 Archived 28 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mordechai ABIR, Ethiopia and the Red Sea, p. 49 https://books.google.com/books?id=7fArBgAAQBAJ&dq=chewa%20ehiopia&pg=PA49 Archived 28 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Deresse Ayenachew, Evolution and Organisation of the Ç̌äwa Military Regiments in Medieval Ethiopia, Annales d'Ethiopie, p. 93, https://www.persee.fr/docAsPDF/ethio_0066-2127_2014_num_29_1_1559.pdf

- ^ Deresse Ayenachew, Evolution and Organisation of the Ç̌äwa Military Regiments in Medieval Ethiopia, Annales d'Ethiopie, p. 88, https://www.persee.fr/docAsPDF/ethio_0066-2127_2014_num_29_1_1559.pdf

- ^ Tsehai Berhane-Selassie, Ethiopian Warriorhood, Boydell & Brewer, p. 104

- ^ "The Rise of Feudalism in Ethiopia". Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ Ellis, Gene (1979). "Feudalism in Ethiopia: A Further Comment on Paradigms and Their Use". Northeast African Studies. 1 (3): 91–97. ISSN 0740-9133. JSTOR 43660024.

- ^ Cohen, John M. (1974). "Ethiopia: A Survey on the Existence of a Feudal Peasantry". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 12 (4): 665–672. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00014312. ISSN 0022-278X. JSTOR 159996. S2CID 154715719.

- ^ Cohen, John M. (1974). "Peasants and Feudalism in Africa: The Case of Ethiopia". Canadian Journal of African Studies. 8 (1): 155–157. doi:10.2307/483880. ISSN 0008-3968. JSTOR 483880.

- ^ Schaefer, Charles (1992). "The Politics of Banking: The Bank of Abyssinia, 1905–1931". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 25 (2): 361–389. doi:10.2307/219391. ISSN 0361-7882. JSTOR 219391.

- ^ Teklemedhin, Fasil Alemayehu and Merhatbeb. "The Birth and Development of Banking Services in Ethiopia". www.abyssinialaw.com. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ^ "Haile Selassie I University – Five Year Plan 1967–1971" (PDF). 4 July 2022.

- ^ "An Overview of Ethiopia's Planning Experience" (PDF). 4 July 2022.

- ^ "Development plans – Ethiopia". African Studies Centre Leiden. 7 August 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ "Industry and Industrialization in Ethiopia: Policy Dynamics and Spatial Distributions" (PDF). 4 July 2022.

- ^ Zekaria, Ahmed (1991). "Harari Coins: A Preliminary Survey". Journal of Ethiopian Studies. 24: 23–46. ISSN 0304-2243. JSTOR 41965992.

- ^ "The Rise of Feudalism in Ethiopia". Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ Lewis, William H. (1956). "The Ethiopian Empire: Progress and Problems". Middle East Journal. 10 (3): 257–268. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4322824.

- ^ "1931 Constitution of Ethiopia" (PDF). 17 September 2022.

- ^ "Revised Constitution of the Empire of Ethiopia" (PDF). 22 September 2022. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ "ETHIOPIA" (PDF). 22 September 2022.

Bibliography

- Adejumobi, Saheed A. (2007). The History of Ethiopia. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32273-0.

- Antonicelli, Franco (1975). Trent'anni di storia italiana: dall'antifascismo alla Resistenza (1915–1945) lezioni con testimonianze [Thirty Years of Italian History: From Antifascism to the Resistance (1915–1945) Lessons with Testimonials]. Reprints Einaudi (in Italian). Torino: Giulio Einaudi Editore. OCLC 878595757.

- Pankhurst, Richard (2001). The Ethiopians: A History. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-631-22493-8.

- Shillington, Kevin (2004). Encyclopedia of African History, Vol. 1. London: Routledge. p. 1912. ISBN 978-1-57958-245-6.

Further reading

- Salvadore, Matteo (2016). The African Prester John and the Birth of Ethiopian-European Relations, 1402–1555. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-4724-1891-3.

External links

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource: - "Abyssinia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. I (9th ed.). 1878.

- "Abyssinia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Ethiopia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Abyssinia". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). 1922.

- "Abyssinia". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch