Economy of France

La Défense, the financial hub of France | |

| Currency | Euro (EUR, €) |

|---|---|

| Calendar year | |

Trade organisations | EU, WTO, G-20, G7 and OECD |

Country group | |

| Statistics | |

| Population | 68,043,000 (February 2023)[5] |

| GDP | |

| GDP rank | |

GDP growth |

|

GDP per capita | |

GDP per capita rank | |

GDP by sector |

|

| |

Population below poverty line |

|

| 29.7 low (2023)[9] | |

Labour force | |

Labour force by occupation |

|

| Unemployment | |

Average gross salary | €3,462 /monthly (2022)[15] |

| €2,468 /monthly (2022)[16][17] | |

Main industries |

|

| External | |

| Exports | $746.9 billion (5th; 2020 est.)[18] |

Export goods | machinery and equipment, aircraft, plastics, chemicals, pharmaceutical products, iron and steel, beverages |

Main export partners |

|

| Imports | $803.6 billion (4th; 2020 est.)[19] |

Import goods | machinery and equipment, vehicles, crude oil, aircraft, plastics, chemicals |

Main import partners |

|

FDI stock | |

| 10.604 billion (2021)[6] | |

Gross external debt | $5.250 trillion (31 March 2017)[20] |

| Public finances | |

| Revenues | 52.5% of GDP (2021)[21] |

| Expenses | 59% of GDP (2021)[21] |

| Economic aid |

|

| 209 billion euro (February 2023)[28] | |

All values, unless otherwise stated, are in US dollars. | |

The economy of France is a highly developed social market economy with notable state participation in strategic sectors.[29] It is the world's seventh-largest economy by nominal GDP and the ninth-largest economy by PPP,[30] constituting around 4% of world GDP.[31] Due to a volatile currency exchange rate, France's GDP as measured in dollars fluctuates sharply, being smaller in 2024 than in 2008. France has a diversified economy,[32] that is dominated by the service sector (which in 2017 represented 78.8% of its GDP), whilst the industrial sector accounted for 19.5% of its GDP and the primary sector accounted for the remaining 1.7%.[33] In 2020, France was the largest Foreign Direct Investment recipient in Europe,[34] and Europe's second largest spender in research and development.[35] It was ranked among the 10 most innovative countries in the world by the 2020 Bloomberg Innovation Index,[36] as well as the 15th most competitive nation globally according to the 2019 Global Competitiveness Report (up 2 notches compared to 2018).[37] It was the fifth-largest trading nation in the world (and second in Europe after Germany). France is also the most visited destination in the world,[38][39] as well as the European Union's leading agricultural power.[40]

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), in 2023, France was the world's 23rd country by GDP per capita with $44,408 per inhabitant. In 2021, France was listed on the United Nations's Human Development Index with a value of 0.903 (indicating very high human development) and 22nd on the Corruption Perceptions Index in 2021.[41][42] Among OECD members, France has a highly efficient and strong social security system, which comprises roughly 31.7% of GDP.[4][43][3]

Paris is a leading global city, and has one of the largest city GDP in the world.[44] It ranks as the first city in Europe (and 3rd worldwide) by the number of companies classified in Fortune's Fortune Global 500.[45] Paris produced US$738 billion (or US$882 billion at market exchange rates) or around 1/3 of the French economy in 2018[46] while the economy of the Paris metropolitan area—the largest in Europe with London—generates around 1/3 of France's GDP or around $1.0 trillion.[47] Paris has been ranked as the 2nd most attractive global city in the world in 2019 by KPMG.[48] La Défense, Paris's Central Business District, was ranked by Ernst & Young in 2017 as the leading business district in continental Europe, and fourth in the world.[49] The OECD is headquartered in Paris, the nation's financial capital. The other major economic centres of the country include Lyon, Toulouse (centre of the European aerospace industry), Marseille and Lille.

France's economy entered the recession of the late 2000s later and appeared to leave it earlier than most affected economies, only enduring four-quarters of contraction.[50] However, France experienced stagnant growth between 2012 and 2014, with the economy expanding by 0% in 2012, 0.8% in 2013 and 0.2% in 2014. Growth picked up in 2015 with a growth of 0.8%. This was followed by a growth of 1.1% for 2016, a growth of 2.2% for 2017, and a growth of 2.1% for 2018.[51]

According to INSEE (2021), non-financial and non-agricultural medium-sized firms employed 3 million full-time equivalent employees (24.3% of the workforce), accounted for 27% of investment, 30% of turnover, and 26% of value added, despite accounting for only 1.6% of total firms in France.[52][53]

Corporations

[edit]With 31 companies that are part of the world's biggest 500 companies, France was in 2020 the most represented European country in the 2020 Fortune Global 500, ahead of Germany (27 companies) and the UK (22).[54]

As of August 2020, France was also the country that weighed the most on the Eurozone's EURO STOXX 50 (representing 36.4% of all total assets), ahead of Germany (35.2%).[55]

Several French corporations rank amongst the largest in their industries such as AXA in insurance and Air France in air transportation.[56] Luxury and consumer goods are particularly relevant, with L'Oreal being the world's largest cosmetic company while LVMH and Kering are the world's two largest luxury product companies. In energy and utilities, GDF-Suez and EDF are amongst the largest energy companies in the world, and Areva is a large nuclear-energy company; Veolia Environnement is the world's largest environmental services and water management company; Vinci SA, Bouygues and Eiffage are large construction companies; Michelin ranks in the top 3 tire manufacturers; JCDecaux is the world's largest outdoor advertising corporation; BNP Paribas, Credit Agricole and Société Générale rank amongst the largest banks in the world by assets. Capgemini and Atos are among the largest technology consulting companies.

Carrefour is the world's second-largest retail group in terms of revenue; Total is the world's fourth-largest private oil company; Lactalis is the world's largest dairy products group; Sanofi is the world's fifth-largest pharmaceutical company; Publicis is the world's third-largest advertising company; Groupe PSA is the world's 6th and Europe's 2nd largest automaker; Accor is the leading European hotel group; Alstom is one of the world's leading conglomerates in rail transport.

In 2022, the sector with the highest number of companies registered in France is Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate with 2,656,178 companies followed by Services and Retail Trade with 2,090,320 and 549,395 companies respectively.[57]

Rise and decline of dirigisme

[edit]France embarked on an ambitious and very successful programme of modernisation under state coordination. This programme of dirigisme, mostly implemented by governments between 1944 and 1983, involved the state control of certain industries such as transportation, energy and telecommunications as well as various incentives for private corporations to merge or engage in certain projects.

The 1981 election of president François Mitterrand saw a short-lived increase in governmental control of the economy, nationalizing many industries and private banks. This form of increased dirigisme, was criticised as early as 1982. By 1983, the government decided to renounce dirigisme and start an era of rigueur ("rigor") or corporation. As a result, the government largely retreated from economic intervention; dirigisme has now essentially receded, though some of its traits remain. The French economy grew and changed under government direction and planning much more than in other European countries.

Despite being a widely liberalised economy, the government continues to play a significant role in the economy: government spending, at 56% of GDP in 2014, is the second-highest in the European Union. Labor conditions and wages are highly regulated. The government continues to own shares in corporations in several sectors, including energy production and distribution, automobiles, aerospace industry, shipbuilding, the arms industry, electronics industry, machine industry, metallurgy, fuels, chemical industry, transportation, and telecommunications.[58][59]

Government finance

[edit]

In April and May 2012, France held a presidential election in which the winner François Hollande had opposed austerity measures, promising to eliminate France's budget deficit by 2017. The new government stated that it aimed to cancel recently enacted tax cuts and exemptions for the wealthy, raising the top tax bracket rate to 75% on incomes over a million euros, restoring the retirement age to 60 with a full pension for those who have worked 42 years, restoring 60,000 jobs recently cut from public education, regulating rent increases; and building additional public housing for the poor.

In June 2012, Hollande's Socialist Party won an overall majority in the legislative elections, giving it the capability to amend the French Constitution and allowing immediate enactment of the promised reforms. French government bond interest rates fell 30% to record lows,[60] less than 50 basis points above German government bond rates.[61]

Hollande's successor as President of France, Emmanuel Macron, a centrist politician, took office in May 2017. His aim was to revive the euro zone’s second-largest economy.[62]

In July 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the French government issued 10-years bonds which had negative interest rates, for the first time in its history (which means that investors buying French bonds will pay, rather than receive, interest for owning French sovereign debt).[63]

France possesses in 2020 the fourth-largest gold reserves in the world.[64]

Macron vowed in May 2023 to build factories, boost job creations and make France more independent, shaked by pension protests.[65]

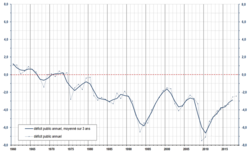

National debt

[edit]The Government of France has run a budget deficit each year since the early 1970s. As of 2021, French government debt reached an equivalent of 118.6% of French GDP.[66]

Under European Union rules, member states are supposed to limit their debt to 60% of output or be reducing the ratio structurally towards this ceiling, and run public deficits of no more than 3.0% of GDP.[67]

In late 2012, credit-rating agencies warned that growing French government debt levels risked France's AAA credit rating, raising the possibility of a future credit downgrade and subsequent higher borrowing costs for the French government.[68] In 2012 France was downgraded by ratings agencies Moody's, Standard & Poor's (S&P), and Fitch to an AA+ credit rating.[69][70]

In December 2014 France's credit rating was further downgraded by Fitch and S&P to AA.[71]

Macron, shaken by pension protests, vowed in May 2023 to build factories, boost job creations and make France more independent.[72]

The Government of France experienced a significant shift in its bond market position on September 26, 2024, when its bond yield surpassed that of Spain for the first time since 2007.[73] The yield on 10-year French bonds reached 2.97%, slightly exceeding the yield on Spanish bonds of similar maturity, despite France's typically higher credit rating. This development raised concerns among investors about France's ability to manage its public finances effectively. France's bond yields were reported to be higher than those of Portugal and approaching levels seen in Italy and Greece, countries traditionally viewed as having higher economic risks in the Eurozone.[73]

Furthermore, France faces a budget crisis in 2024, with the deficit at risk of exceeding 6% of GDP, significantly higher than the previous government's estimate of 5.1%. Newly appointed Finance Minister Antoine Armand and Budget Minister Laurent Saint-Martin pledged to focus on spending cuts before considering tax increases to address the fiscal shortfall. Prime Minister Michel Barnier was tasked with finalizing the 2025 budget within days, amidst pressure to present realistic plans for deficit reduction.[74]

Data

[edit]

The following table shows the main economic indicators in 1980–2021 (with IMF staff estimates in 2022–2027). Inflation below 5% is in green.[75]

| Year | GDP (in bn. US$PPP | GDP per capita (in US$PPP) | GDP (in bn. US$nominal) | GDP per capita (in US$ nominal) | GDP growth (real) | Inflation rate (% per annum) | Unemployment rate | Government debt (% of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 578.2 | 10,761.0 | 702.2 | 13,069.5 | 6.3% | 20.8% | ||

| 1981 | ||||||||

| 1982 | ||||||||

| 1983 | ||||||||

| 1984 | ||||||||

| 1985 | ||||||||

| 1986 | ||||||||

| 1987 | ||||||||

| 1988 | ||||||||

| 1989 | ||||||||

| 1990 | ||||||||

| 1991 | ||||||||

| 1992 | ||||||||

| 1993 | ||||||||

| 1994 | ||||||||

| 1995 | ||||||||

| 1996 | ||||||||

| 1997 | ||||||||

| 1998 | ||||||||

| 1999 | ||||||||

| 2000 | ||||||||

| 2001 | ||||||||

| 2002 | ||||||||

| 2003 | ||||||||

| 2004 | ||||||||

| 2005 | ||||||||

| 2006 | ||||||||

| 2007 | ||||||||

| 2008 | ||||||||

| 2009 | ||||||||

| 2010 | ||||||||

| 2011 | ||||||||

| 2012 | ||||||||

| 2013 | ||||||||

| 2014 | ||||||||

| 2015 | ||||||||

| 2016 | ||||||||

| 2017 | ||||||||

| 2018 | ||||||||

| 2019 | ||||||||

| 2020 | ||||||||

| 2021 | ||||||||

| 2022 | ||||||||

| 2023 | ||||||||

| 2024 | ||||||||

| 2025 | ||||||||

| 2026 | ||||||||

| 2027 |

Economic sectors

[edit]Industry

[edit]

In 2019, France was the world's 8th largest manufacturer in terms of value added, according to the World Bank.[76]

The leading industrial sectors in France are telecommunications (including communication satellites), aerospace and defence, ship building, pharmaceuticals, construction and civil engineering, chemicals, textiles, and automobile production. The chemical industry is a key sector for France, helping to develop other manufacturing activities and contributing to economic growth.[77]

Research and development spending is also high in France at 2.26% of GDP, the fourth-highest in the OECD.[78]

Industry contributes to French exports: as of 2018, the Observatory of Economic Complexity estimates that France's largest exports "are led by planes, helicopters, and spacecraft ($43.8 billion), cars ($26 billion), packaged medicaments ($25.7 billion), vehicle parts ($16.5 billion), and gas turbines ($14.4 billion)."[79]

In December 2023, industrial production in France experienced its most significant change since May of the same year, with a notable increase of 1.1%.[80]

Energy

[edit]2021 electricity production of France[81]

France is the world-leading country in nuclear energy, home of global energy giants Areva, EDF and GDF Suez: nuclear power now accounts for about 78% of the country's electricity production, up from only 8% in 1973, 24% in 1980, and 75% in 1990. Nuclear waste is stored on site at reprocessing facilities. Due to its heavy investment in nuclear power, France is the smallest emitter of carbon dioxide among the seven most industrialised countries in the world.[82] Due to its overwhelming reliance on nuclear power, renewable energies have seen relatively little growth compared to other Western countries.

In 2006, electricity generated in France amounted to 548.8 TWh, of which:[83]

- 428.7 TWh (78.1%) were produced by nuclear power generation

- 60.9 TWh (11.1%) were produced by hydroelectric power generation

- 52.4 TWh (9.5%) were produced by fossil-fuel power generation

- 21.6 TWh (3.9%) by coal power

- 20.9 TWh (3.8%) by natural-gas power

- 9.9 TWh (1.8%) by other fossil fuel generation (fuel oil and gases by-products of industry such as blast furnace gases)

- 6.9 TWh (1.3%) were produced by other types of power generation (essentially waste-to-energy and wind turbines)

- The electricity produced by wind turbines increased from 0.596 TWh in 2004, to 0.963 TWh in 2005, and 2.15 TWh in 2006, but this still accounted only for 0.4% of the total production of electricity (as of 2006).

In November 2004, EDF (which stands for Electricité de France), one of the world's largest utility company and France's largest electricity provider, was floated with huge success on the French stock market. However, the French state still retains 70% of the capital. Other electricity providers include Compagnie nationale du Rhône (CNR) and Endesa (through SNET).

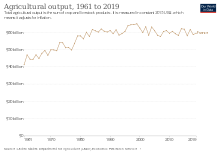

Agriculture

[edit]

France is the world's sixth largest agricultural producer and EU's leading agricultural power, accounting for about one-third of all agricultural land within the EU. In the early 1980s, France was the leading producer of the three principal grains of wheat, barley, and maize. Back in 1983, France produced around 24.8 million tonnes, ahead of the United Kingdom and West Germany, the next two largest wheat producers.[84]

Northern France is characterised by large wheat farms. Dairy products, pork, poultry, and apple production are concentrated in the western region. Beef production is located in central France, while the production of fruits, vegetables, and wine ranges from central to southern France. France is a large producer of many agricultural products and is currently expanding its forestry and fishery industries. The implementation of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) have resulted in reforms in the agricultural sector of the economy.

As the world's second-largest agricultural exporter, France ranks just after the United States.[85] The destination of 49% of its exports is other EU members states. France also provides agricultural exports to many poor African countries (including its former colonies) which face serious food shortages. Wheat, beef, pork, poultry, and dairy products are the principal exports.

Exports from the United States face stiff competition from domestic production, other EU member states, and third-world countries in France. US agricultural exports to France, totaling some $600 million annually, consist primarily of soybeans and soybean products, feeds and fodders, seafood, and consumer products, especially snack foods and nuts. French exports to the United States are much more high-value products such as its cheese, processed products and its wine.

The French agricultural sector receives almost €11 billion in EU subsidies. France produced in 2018 39.5 million tons of sugar beet (2nd largest producer in the world, just behind Russia), which serves to produce sugar and ethanol; 35.8 million tons of wheat (5th largest producer in the world); 12.6 million tons of maize (11th largest producer in the world); 11.2 million tons of barley (2nd largest producer in the world, only behind Russia); 7.8 million tons of potato (8th largest producer in the world); 6.2 million tons of grape (5th largest producer in the world); 4.9 million tons of rapeseed (4th largest producer in the world, behind Canada, China and India); 2.2 million tons of sugarcane; 1.7 million tons of apple (9th largest producer in the world); 1.3 million tons of triticale (4th largest producer in the world, only behind Poland, Germany and Belarus); 1.2 million tons of sunflower seed (9th largest producer in the world); 712 thousand tons of tomatoes; 660 thousand tons of linen; 615 thousand tons of dry pea; 535 thousand tons of carrot; 427 thousand tons of oats; 400 thousand tons of soy; in addition to smaller productions of other agricultural products.[86]

Tourism

[edit]

France is the world's most popular tourist destination with more than 83.7 million foreign tourists in 2014,[87] ahead of Spain (58.5 million in 2006) and the United States (51.1 million in 2006). This figure excludes people staying less than 24 hours in France, such as northern Europeans crossing France on their way to Spain or Italy during the summer.

According to figures from 2003, some popular tourist sites include (in visitors per year):[88] Eiffel Tower (6.2 million), Louvre Museum (5.7 million), Palace of Versailles (2.8 million), Cité des Sciences et de l'Industrie (2.6 million), Musée d'Orsay (2.1 million), Arc de Triomphe (1.2 million), Centre Pompidou (1.2 million), Mont-Saint-Michel (1 million), Château de Chambord (711,000), Sainte-Chapelle (683,000), Château du Haut-Kœnigsbourg (549,000), Puy de Dôme (500,000), Musée Picasso (441,000), Carcassonne (362,000). However, the most popular site in France is Disneyland Paris, with 9.7 million visitors in 2017[89]

Arms industry

[edit]

The French government is the French arms industry's main customer, mainly buying warships, guns, nuclear weapons and equipment.

During the 2000–2015 period, France was the fourth largest weapons exporter in the world.[90][91]

French manufacturers export great quantities of weaponry to Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Brazil, Greece, India, Pakistan, Taiwan, Singapore and many others. It was reported that in 2015, French arms sales internationally amounted to 17.4 billion U.S. dollars,[92] more than double the figure of 2014.[93]

Fashion and luxury goods

[edit]According to 2017 data compiled by Deloitte, Louis Vuitton Moet Hennessey (LVMH), a French brand, is the largest luxury company in the world by sales, selling more than twice the amount of its nearest competitor.[94] Moreover, France also possesses 3 of the top 10 luxury goods companies by sales (LVMH, Kering SA, L'Oréal), more than any other country in the world.[94]

Paris is considered one of the world's foremost fashion capitals, or even "the world's fashion capital".[95] The French tradition for haute couture has been estimated to start as early as the era of Louis XIV, the Sun King.[96]

Education

[edit]Education in France is organised in a highly centralised manner, with many subdivisions.[97] It is divided into the three stages of primary education (enseignement primaire), secondary education (enseignement secondaire), and higher education (enseignement supérieur). In French higher education, the following degrees are recognised by the Bologna Process (EU recognition): Licence and Licence Professionnelle (bachelor's degrees), and the comparably named Master and Doctorat degrees.[98]

The Programme for International Student Assessment coordinated by the OECD currently ranks the overall knowledge and skills of French 15-year-olds as 26th in the world in reading literacy, mathematics, and science, near the OECD average of 493.[99] France's performance in mathematics and science at the middle school level was ranked 23 in the 1995 Trends in International Math and Science Study.[100]

The OECD also found that students in France reported greater concern about discipline and behaviour at school and in classrooms, much more than the rest of Europe.[102] This was higher than all OECD countries.[103][102] School principals reported higher staff and material shortage in France, higher than OECD averages.[102] About 7% of French teachers believe the teaching profession is highly valued in France and in society.[104][102] School principals noted regular acts of violence/ bullying among their students, higher than averages.[104] The time spent of teaching time spent on keeping classes in good order is one of the largest in France, among all OECD countries studied.[104][102] France also has a high drop out rate.[104][105]

Pupils can take apprenticeships to enter the labour market with the Baccalauréat Technologique. It allows pupils pursue short and technical studies (laboratory, design and applied arts, hotel and restaurant, management etc).

Higher education in France was reshaped by the student revolts of May 1968. During the 1960s, French public universities responded to a massive explosion in the number of students (280,000 in 1962–63 to 500,000 in 1967–68) by stuffing approximately one-third of their students into hastily developed campus annexes (roughly equivalent to American satellite campuses) which lacked decent amenities, resident professors, academic traditions, or the dignity of university status.[106] This is why the French higher education economy performs poorly compared with other high-performing countries such as England or Australia. France also hosts various catholic universities recognised by the state, the largest one being Lille Catholic University,[107] as well branch colleges of foreign universities. They include Baruch College, the University of London Institute in Paris, Parsons Paris School of Art and Design and the American University of Paris. Eighteen million pupils and students are in the education system, over 2.4 million of whom are in higher education.[108]

Transport

[edit]

Transportation in France relies on one of the densest networks in the world with 146 km of road and 6.2 km of rail lines per 100 km2. It is built as a web with Paris at its centre.[109] The highly subsidised rail transport network makes up a relatively small portion of travel, most of which is done by car. However, the high-speed TGV trains make up a large proportion of long-distance travel, partially because intercity buses were prevented from operating until 2015.

With 3,220 kilometers of high-speed train lines, France boast the 2nd most expansive network in the world, only after China.[110] Charles de Gaulle Airport is one of the busiest airports in the world by passenger traffic.[111] Charles de Gaulle airport is third globally in the number of destinations served, and first in the number of countries served with non-stop flights.[112]

France also boasts a number of seaports and harbours, including Bayonne, Bordeaux, Boulogne-sur-Mer, Brest, Calais, Cherbourg-Octeville, Dunkerque, Fos-sur-Mer, La Pallice, Le Havre, Lorient, Marseille, Nantes, Nice, Paris, Port-la-Nouvelle, Port-Vendres, Roscoff, Rouen, Saint-Nazaire, Saint-Malo, Sète, Strasbourg and Toulon. There are approximately 470 airports in France and by a 2005 estimate, there are three heliports. 288 of the airports have paved runways, with the remaining 199 being unpaved. The national carrier of France is Air France, a full service global airline which flies to 20 domestic destinations and 150 international destinations in 83 countries (including Overseas France) across all 6 major continents.

Foreign investment

[edit]According to a study conducted by Ernst & Young, France was in 2020 the largest Foreign Direct Investment recipient in Europe, ahead of the UK and Germany.[34] EY attributed this as a "direct result of President Macron’s reforms of labor laws and corporate taxation, which were well received by domestic and international investors alike."[34]

France scored 5th in the 2019 AT Kearney FDI Confidence Index, up 2 notches from its 2017 ranking.[113]

Labour market

[edit]According to a 2011 report by the American Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), France's GDP per capita at purchasing power parity is similar to that of the UK, with just over US$35,000 per head.[114] To explain why French per capita GDP is lower than that of the United States, the economist Paul Krugman stated that "French workers are roughly as productive as US workers", but that the French have a lower workforce participation rate, and "when they work, they work fewer hours". According to Krugman, the difference is due to the French making "different choices about retirement and leisure".[115]

France has long suffered a relatively high unemployment rate,[116] even during the years when its macroeconomic performances compared favourably with other advanced economies.[117] French employment rates for the working age population is one of the lowest of the OECD countries: in 2020, only 64.4% of the French working age population were in employment, compared to 77% in Japan, 76.1% in Germany, 75.4% in the UK, but the French employment rate was higher than that of the US, which stood at 62.5%.[118] This gap is due to the low employment rate for 15–24 years old: 38% in 2012, compared to 47% in the OECD.

Since his election in 2017, Emmanuel Macron has introduced several labour market reforms which proved successful in decreasing the unemployment rate before the global COVID-19 recession struck.[119] In late 2019, the French unemployment rate, though still high compared to other developed economies, was the lowest in a decade.[120]

During the 2000s and 2010s, classical liberal and Keynesian economists sought out different solutions to the unemployment issue in France. Keynesian economists's theories led to the introduction of the 35-hour workweek law in 1999. Between 2004 and 2008, the government attempted to combat unemployment with supply-side reforms, but was met with fierce resistance;[121] the contrat nouvelle embauche and the contrat première embauche (which allowed more flexible contracts) were of particular concern, and both were eventually repealed.[122] The Sarkozy government used the revenu de solidarité active (in-work benefits) to redress the negative effect of the revenu minimum d'insertion (unemployment benefits which do not depend on previous contributions, unlike normal unemployment benefits in France) on the incentive to accept even jobs which are insufficient to earn a living.[123] Neoliberal economists attribute the low employment rate, particularly evident among young people, to high minimum wages that would prevent low productivity workers from easily entering the labour market.[124]

A December 2012 New York Times article reported on a "floating generation" in France that formed part of the 14 million unemployed young Europeans documented by the Eurofound research agency.[125] This floating generation was attributed to a dysfunctional system: "an elitist educational tradition that does not integrate graduates into the work force, a rigid labour market that is hard to enter for newcomers, and a tax system that makes it expensive for companies to hire full-time employees and both difficult and expensive to lay them off".[126] In July 2013, the unemployment rate for France was 11%.[127]

In early April 2014, employers' federations and unions negotiated an agreement with technology and consultancy employers, as employees had been experiencing an extension of their work time through smartphone communication outside of official working hours. Under a new, legally binding labour agreement, around 250,000 employees will avoid handling work-related matters during their leisure time and their employers will, in turn, refrain from engaging with staff during this time.[128]

Every day, about 80,000 French citizens are commuting to work in neighbouring Luxembourg, making it the biggest cross-border workforce group in the whole of the European Union.[129] They are attracted by much higher wages for the different job groups than in their own country and the lack of skilled labour in the booming Luxembourgish economy.

The background of the 2023 pension reform was about 14% of GDP pension spending in France compared to OECD average of just over 9%. The aim of the pension reform was to reduce cost by increasing the minimum legal retirement age from 62 years to 64 years in 2030.[130] In April 2023, president Emmanuel Macron signed the pension reforms into law.[131]

External trade

[edit]In 2018, France was the 5th largest trading nation in the world, as well as the second-largest trading nation in Europe (after Germany).[132] Its foreign trade balance for goods had been in surplus from 1992 until 2001, reaching $25.4 billion (25.4 G$) in 1998; however, the French balance of trade was hit by the economic downturn, and went into the red in 2000, reaching a US$15bn deficit in 2003. Total trade for 1998 amounted to $730 billion, or 50% of GDP—imports plus exports of goods and services. Trade with European Union countries accounts for 60% of French trade.

In 1998, US–France trade stood at about $47 billion – goods only. According to French trade data, US exports accounted for 8.7% – about $25 billion – of France's total imports. US industrial chemicals, aircraft and engines, electronic components, telecommunications, computer software, computers and peripherals, analytical and scientific instrumentation, medical instruments and supplies, broadcasting equipment, and programming and franchising are particularly attractive to French importers.

The principal French exports to the US are aircraft and engines, beverages, electrical equipment, chemicals, cosmetics, luxury products and perfume. France is the ninth-largest trading partner of the US.

|

|

|

In August 2023, the French current account deficit shrank by €29.7 billion in the past six months, from −€39.3 billion to −€9.6 billion, primarily due to a fall in energy prices.[134]

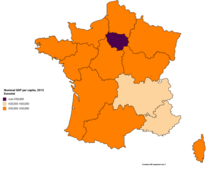

Regional economy

[edit]

The economic disparity between French regions is not as high as that in other European countries such as the UK, Italy or Germany, and higher than in countries like Sweden or Denmark, or even Spain. However, Europe's wealthiest and second largest regional economy, Ile-de-France (the region surrounding Paris), has long profited from the capital city's economic hegemony.

The most important régions are Île-de-France (Europe's 4th regional economy), Rhône-Alpes (Europe's 5th largest regional economy thanks to its services, high-technologies, chemical industries, wines, tourism), Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur (services, industry, tourism and wines), Nord-Pas-de-Calais (European transport hub, services, industries) and Pays de la Loire (green technologies, tourism). Regions like Alsace, which has a rich past in industry (machine tool) and currently stands as a high income service-specialised region, are very wealthy without ranking very high in absolute terms.

The rural areas are mainly in Auvergne, Limousin, and Centre-Val de Loire, and wine production accounts for a significant proportion of the economy in Aquitaine (Bordeaux (or claret)), Burgundy, and champagne produced in Champagne-Ardennes.

| Rank | Region | GDP (millions of euros, 2015)[136] | GDP per capita (euros, 2015)[136][137] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Île de France | 671,048 | 55,433 |

| 2 | Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes | 250,197 | 31,666 |

| 3 | Nouvelle-Aquitaine | 163,140 | 27,527 |

| 4 | Occitanie | 159,326 | 27,497 |

| 5 | Hauts-de-France | 157,316 | 26,170 |

| 6 | Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur | 154,081 | 30,709 |

| 7 | Grand Est | 151,880 | 27,317 |

| 8 | Pays de la Loire | 109,965 | 29,482 |

| 9 | Normandy | 91,810 | 27,495 |

| 10 | Brittany | 91,406 | 27,684 |

| 11 | Bourgogne-Franche-Comté | 74,074 | 26,258 |

| 12 | Centre-Val de Loire | 70,230 | 27,226 |

| Réunion | 18,373 | 21,559 | |

| Guadeloupe | 9,724 | 22,509 | |

| Martinique | 9,289 | 24,516 | |

| 13 | Corsica | 8,761 | 26,629 |

| French Guiana | 4,441 | 16,777 | |

| Mayotte | 2,309 | 9,755 |

Departments economy and cities

[edit]Departmental income inequalities

[edit]

In terms of income, important inequalities can be observed among the French départements.

According to the 2008 statistics of the INSEE, the Yvelines is the highest income department of the country with an average income of €4,750 per month. Hauts-de-Seine comes second, Essonne third, Paris fourth, Seine-et Marne fifth. Île-de-France is the wealthiest region in the country with an average income of €4,228 per month (and is also the wealthiest region in Europe) compared to €3,081 at the national level. Alsace comes second, Rhône-Alpes third, Picardy fourth, and Upper Normandy fifth.

The poorest parts of France are the French overseas departments, French Guiana being the poorest department with an average household income of €1,826. In Metropolitan France it is Creuse in the Limousin region which comes bottom of the list with an average household income of €1,849 per month.[138]

Urban income inequalities

[edit]Huge inequalities can also be found among cities. In the Paris metropolitan area, significant differences exist between the higher standard of living of Paris Ouest and lower standard of living in areas in the northern banlieues of Paris such as Seine-Saint-Denis.

For cities of over 50,000 inhabitants, Neuilly-sur-Seine, a western suburb of Paris, is the wealthiest city in France with an average household income of €5,939, and 35% earning more than €8,000 per month.[139] But within Paris, four arrondissements surpass wealthy Neuilly-sur-Seine in household income: the 6th, the 7th, the 8th and the 16th; the 8th arrondissement being the wealthiest district in France (the other three following it closely as 2nd, 3rd and 4th wealthiest ones).

Poverty

[edit]OECD data from 2021 estimate that 8.4% of the French population lived in poverty, compared with 18% in the United States, 11.6% in Canada, and 9.8% in Germany.[140] In 2016, the poverty rate in France stood at 14%, compared to 12.8% in 2004.[141] The northern districts of Marseille represent one of the poorest and unequal areas in France, where poor neighbourhoods rub shoulders with wealthier pockets. The share of people living below the poverty line (949 euro per month) was 28.8% in 2008 in sensitive urban zones (ZUS) compared to 12% in the rest of the territory.[142]

In comparison with the average French workers, foreign workers tended to be employed in the hardest and lowest-paid jobs. They also live in poor conditions. A 1972 study found that foreign workers earned 17% less than their French counterparts, although this national average concealed the extent of inequality. Foreign workers were more likely to be men in their prime working years in the industrial areas, which generally had higher rates of pay than elsewhere.[143]

Wealth

[edit]Overview

[edit]In 2010, the French had an estimated wealth of US$14.0 trillion for a population of 63 million.[144]

- In terms of aggregate wealth, the French are the wealthiest Europeans, accounting for more than a quarter of wealthiest European households.[145] Globally, the French nation ranks fourth-wealthiest.[146][147]

- In 2010, wealth per French adult was a little higher than $290,000, down from a pre-crisis high of $300,000 in 2007. According to this ratio, the French are the wealthiest in Europe. The wealth tax is paid by 1.1 million people in France. Liability to this tax starts from €1.3 million of assets. (There is a discount on the principal residence value.)

- Almost every French household has at least $1,000 in assets.[148] Proportionally, there are twice as many French with assets of over $10,000 and four times as many French with assets of over $100,000 than the world average.[149]

Millionaires

[edit]France has the third-highest number of millionaires in Europe as of 2017. There were 1.617 million millionaire households (measured in US dollars) living in France in 2017, behind the UK (2.225 million) and Germany (1.637 million).[150]

The wealthiest man in France is the LVMH CEO and owner Bernard Arnault.

By 2022, the combined wealth of France's 500 richest people will be worth 1,170 billion euros, or 45% of GDP. In 2009, this figure was just 194 billion, representing 10% of GDP at the time.[152]

See also

[edit]- Economic impacts of climate change in France

- Economy of French Guiana, French Polynesia, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Mayotte, New Caledonia, Réunion, Saint Barthélemy, Saint Martin, Saint Pierre and Miquelon or Wallis and Futuna

- Economy of Paris

- Economy of Europe

- Economy of the European Union

References

[edit]- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ "World Bank Country and Lending Groups". datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. World Bank. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ a b "Social Expenditure – Aggregated data". OECD.

- ^ a b Kenworthy, Lane (1999). "Do Social-Welfare Policies Reduce Poverty? A Cross-National Assessment" (PDF). Social Forces. 77 (3): 1119–1139. doi:10.2307/3005973. JSTOR 3005973. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2013.

- ^ "Titre | Insee". www.insee.fr. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "The World Factbook". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 16 March 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "People at risk of poverty or social exclusion". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat.

- ^ "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income – EU-SILC survey". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat.

- ^ a b "Human Development Report 2023/2024" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ "Corruption Perceptions Index". Transparency International. 30 January 2024. Archived from the original on 30 January 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ "Labor force, total – France". data.worldbank.org. World Bank & ILO. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ "Employment rate by sex, age group 20-64". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ a b "Euro area unemployment at 6.5" (PDF). Eurostat. May 2023. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ "Home".

- ^ "Taxing Wages 2023: Indexation of Labour Taxation and Benefits in OECD Countries | READ online".

- ^ "Home".

- ^ "Country Comparisons - Exports". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 9 January 2022. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ "Country Comparisons - Imports". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 8 January 2022. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ "Banque de France". Archived from the original on 17 November 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ a b c d "French Economy Dashboard - Public Finance". Insee. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Sovereign Ratings List". Standard & Poor's. 6 January 2017. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2015. Note: this source is continually updated.

- ^ "Moody's downgrades France's government bond ratings to Aa2 from Aa1; outlook changed to stable from negative". Moody's Investors Service. 1 September 2015. Archived from the original on 21 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ "France's credit downgraded to AA at Fitch Ratings – MarketWatch". Archived from the original on 13 December 2014. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ "Scope downgrades France's long-term ratings to AA- and revises the Outlooks to Stable". Retrieved 20 October 2024.

- ^ "Les réserves nettes de change". Direction générale du Trésor. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ Prasad, Monica (2006). The Politics of Free Markets: The Rise of Neoliberal Economic Policies in Britain, France, Germany, and the United States. University of Chicago Press. p. 328. ISBN 9780226679020. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2022". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. October 2022. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ "Global Economy Watch - Projections > Real GDP / Inflation > Share of 2016 world GDP". PWC. Archived from the original on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ^ Country profile: France Archived 1 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Euler Hermes

- ^ Country profil: France Archived 16 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine, CIA World factbook

- ^ a b c How can Europe reset the investment agenda now to rebuild its future? Archived 19 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine, EY, 28 May 2020

- ^ How does your country invest in R&D ? Archived 23 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine, UNESCO Institute for Statistics (retrieved on 27 September 2020)

- ^ These are the world's most innovative countries Archived 24 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Business Insider

- ^ "The Global Competitiveness Report 2019" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ "Tourism industry sub-sectors: COUNTRY REPORT – FRANCE" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 February 2015.

- ^ "UNWTO Tourism Highlights 2014 Edition" (PDF). 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2014.

- ^ France: the market Archived 19 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Société Générale (latest Update: September 2020)

- ^ "Human Development Index 2018 Statistical Update". hdr.undp.org. United Nations Development Programme. Archived from the original on 18 November 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "Corruption Perceptions Index 2018 Executive summary p. 2" (PDF). transparency.org. Transparency International. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Moller, Stephanie; Huber, Evelyne; Stephens, John D.; Bradley, David; Nielsen, François (2003). "Determinants of Relative Poverty in Advanced Capitalist Democracies". American Sociological Review. 68 (1): 22–51. doi:10.2307/3088901. JSTOR 3088901.

- ^ The global geography of world cities Archived 14 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine, iied, 9 July 2020

- ^ 10 reasons to move to Paris La Défense Archived 4 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Official website of Paris La Défense

- ^ "Database - Regions - Eurostat". Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Global Wealth PPP Distribution: Who Are The Leaders Of The Global Economy? - Full Size". www.visualcapitalist.com. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ^ Global Cities Investment Monitor 2019 Archived 20 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine, KPMG, 2019

- ^ The attractiveness of world-class business districts: Paris La Défense vs. its global competitors Archived 18 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine, EY, November 2017

- ^ "Germany, France pull out of recession". CNN. 13 August 2009. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ "5. Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". International Monetary Fund. Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (10 January 2024). Hidden champions, missed opportunities: Mid-caps' crucial role in Europe's economic transition. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5731-8.

- ^ "Gross value added, compensation of employees and domestic employment by industry in 2021 − The national accounts in 2021 | Insee". www.insee.fr. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ "Global 500". Fortune. Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ EURO STOXX 50 Archived 1 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine, 31 August 2020

- ^ "Global 2000 Leading Companies". Forbes. May 2015. Archived from the original on 23 April 2011.

- ^ "Industry Breakdown of Companies in France". HitHorizons.

- ^ "L'Agence des participations de l'État". Archived from the original on 19 April 2022. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ "Groupe Caisse des Dépôts | Ensemble, faisons grandir la France". Archived from the original on 23 April 2022. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ Bloomberg (2012) French government bond interest rates Archived 7 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine (graph)

- ^ Bloomberg (2012) German government bond interest rates Archived 6 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine (graph)

- ^ "Measuring France under Macron". Reuters. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ France issues first 10-year bond at negative interest rate Archived 19 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine, France 24, 4 July 2020

- ^ Top 10 Countries with Largest Gold Reserves Archived 8 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, US Global Investors, September 2020

- ^ "Macron vows to build back factories, boost France's economy shaken by pension protests". Associated Press News. 15 May 2023.

- ^ "World Economic Outlook – General government gross debt". imf.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "French debt jumps, minister promises to meet deficit target". FRANCE 24. 28 September 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ John, Mark (26 October 2012). "Analysis: Low French borrowing costs risk negative reappraisal". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ^ "France loses AAA rating as euro governments downgraded". BBC News. 13 January 2012. Archived from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ Deen, Mark (12 July 2013). "France Loses Top Credit Rating as Fitch Cites Lack of Growth". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ^ Deenpattern dots, Mark (12 December 2014). "France's Credit Rating Cut by Fitch to 'AA'; Outlook Stable". Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ "Macron vows to build back factories, boost France's economy shaken by pension protests". Associated Press. 15 May 2023.

- ^ a b "France's Bond Yield Surpasses Spain's for First Time Since 2007". Bloomberg News. 26 September 2024. Retrieved 26 September 2024.

- ^ "Stepping into budget crisis, French ministers pledge spending cuts". Reuters. 26 September 2024. Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". Archived from the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ "Manufacturing, value added (current US$) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 7 January 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ "Chemical industry" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 August 2010.

- ^ "France in the United States: Economy". Embassy of France in Washington. Archived from the original on 9 October 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ Country profile: France Archived 21 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Observatory of Economic Complexity (page retrieved on 28 September 2020)

- ^ "French industry receives a boost after slow GDP growth". euronews. 2 February 2024. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ "Electricity generation by source, France 1990-2021". Archived from the original on 23 February 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ "CO2 emissions per capita in 2006". Environmental Indicators: Greenhouse Gas Emissions. United Nations. August 2009. Archived from the original on 10 March 2010. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- ^ Source: L’Electricité en France en 2006 : une analyse statistique Archived 26 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ilbery, Brian (1986). Western Europe. New York, United States: Oxford University Press, New York. pp. Pg. 41-42. ISBN 0-19-823278-0.

- ^ "France 2 Actualités & société - Tous les vidéos et replay | France tv". www.france.tv. Archived from the original on 18 September 2009. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "FAOSTAT". www.fao.org. Archived from the original on 12 November 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "La France toujours premiere destination touristique au monde". lefigaro.fr. 8 April 2015. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ "Musées et Monuments historiques". Archived from the original on 24 December 2007.

- ^ "Disneyland Park Paris attendance". Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ SIPRI Arms Transfers Database Archived 14 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine, data 2000–10. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute

- ^ Arms trade: One chart that shows the biggest weapons exporters of the last five years Archived 15 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Independent

- ^ France doubles arms sales in 2015 Archived 21 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, UPI.com

- ^ Arms sales becoming France's new El Dorado, but at what cost? Archived 21 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, France24

- ^ a b Global Powers of Luxury Goods 2019: Bridging the gap between the old and the new Archived 26 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Deloitte

- ^ Top 10 Global Fashion Capitals Archived 21 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Fashion schools

- ^ The King of Couture: How Louis XIV invented fashion as we know it Archived 24 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine, The Atlantic

- ^ "France". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ^ "French higher educational system". Campus France. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ "PISA 2018 Results Combined Executive Summaries Volume I, II & III" (PDF). OECD. 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 December 2019.

- ^ "TIMSS 1995 Highlights of Results for the Middle School Years". timss.bc.edu. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ Flochlay, Anne-Claire. "Université Grenoble Alpes". Université Grenoble Alpes. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) France" (PDF). OECD.

- ^ "PISA 2018 Results: Combined Executive Summaries Volume I, II & III" (PDF). OECD. 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Education GPS - France - Teachers and teaching conditions, primary and lower secondary education (TALIS 2018)".

- ^ "French schools falling further behind, shows major new study". connexionfrance. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ Legois, Jean-Philippe; Monchablon, Alain (2018). "From the Struggle against Repression to the 1968 General Strike in France". In Dhondt, Pierre; Boran, Elizabethanne (eds.). Student Revolt, City, and Society in Europe: From the Middle Ages to the Present. New York: Routledge. pp. 67–78. ISBN 9781351691031. Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "Campus France - Lille Catholic University" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ Kabla-Langlois, Isabelle; Dauphin, Laurence (2015). "Students in higher education". Higher education & research in France, facts and figures - 49 indicators (8). Paris: Ministère de l'Éducation nationale, de l'Enseignement supérieur et de la Recherche: 32–33. Archived from the original on 24 November 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ Les grands secteurs économiques Archived 23 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine Ministère des Affaires étrangères Retrieved 4 November 2007

- ^ Fact Sheet: High Speed Rail Development Worldwide Archived 29 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Environmental and Energy Institute

- ^ 2019 Annual Airport Traffic Report (PDF). United States: Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ "Frankfurt and Paris CDG lead global analysis of airports in S17". anna.aero. 15 February 2017. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ The 2019 Kearney Foreign Direct Investment Confidence Index: Facing a growing paradox Archived 20 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine, AT Kearney

- ^ "International Comparisons of GDP per Capita, and per Hour, 1960–2011" (PDF). Bureau of Labor Statistics. 7 November 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- ^ Paul Krugman (28 January 2011). "GDP Per Capita, Here and There". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- ^ Hélène Baudchon, France: unemployment, a deep-rooted problem. Archived 21 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine. BNP Paribas's Economic Research department, February 2015.

- ^ Reza Moghadam, Why is Unemployment in France so High? Archived 17 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, IMF eLibrary, May 1994

- ^ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2020). "OECD Employment rate" (PDF). Archived from the original on 23 April 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ Emmanuel Macron's reforms are working, but not for him Archived 23 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine, The Economist, 20 February 2020

- ^ Hannah Copeland, Valentina Romei, Macron's labour market changes begin to bear fruit Archived 28 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Financial Times, October 2019

- ^ "More than 1 million protest French jobs law". CNN. Archived from the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch