Alessandro (opera)

Alessandro (HWV 21), is an opera composed by George Frideric Handel in 1726 for the Royal Academy of Music. Paolo Rolli's libretto is based on the story of Ortensio Mauro's La superbia d'Alessandro. This was the first time the famous singers Faustina Bordoni and Francesca Cuzzoni appeared together in one of Handel's operas. The original cast also included Francesco Bernardi who was known as Senesino.

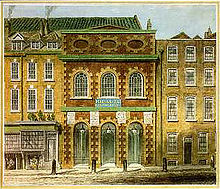

Handel had originally planned Alessandro to be his first contribution to the 1725/1726 season of the Royal Academy. Bordoni did not arrive in London in time to stage it, so Handel substituted his own Scipione in March and April 1726 until her arrival. The opera received its first performance on 5 May 1726 at the King's Theatre, London,[1] and was received "with great applause".[2]

The story recounts Alexander the Great's journey to India and depicts him less in a heroic vein than as vainglorious as well as indecisive in matters of the heart. The work's charm and lightness of touch make it at times almost a comic work.[3] Handel would later revisit the subject of Alexander in his 1736 English-language ode, Alexander's Feast.

Background

[edit]

The German-born Handel, after spending some of his early career composing operas and other pieces in Italy, settled in London, where in 1711 he had brought Italian opera for the first time with his opera Rinaldo. A tremendous success, Rinaldo created a craze in London for Italian opera seria, a form focused overwhelmingly on solo arias for the star virtuoso singers. In 1719, Handel was appointed music director of an organisation called the Royal Academy of Music (unconnected with the present day London conservatoire), a company under royal charter to produce Italian operas in London. Handel was not only to compose operas for the company but hire the star singers, supervise the orchestra and musicians, and adapt operas from Italy for London performance.[4][5]

Handel had composed numerous Italian operas for the academy, with varying degrees of success; some were enormously popular. In February 1726 Handel revived his Ottone, which had been spectacularly successful at its first performances in 1723 and was again a hit at its revival, with a London newspaper reporting

Handel had the satisfaction of seeing an Old Opera of his not only fill the House, which had not been done for some time, but above three hundred turn'd away for want of room.[2]

As the newspaper notes, full houses were by no means a regular occurrence by that time, and the directors of the Royal Academy of Music decided to increase audiences' interest by bringing another celebrated international opera star, Italian soprano Faustina Bordoni, to join established London favourites Francesca Cuzzoni and the star castrato Senesino in the company's performances. Many opera companies in Italy featured two leading ladies in one opera and Faustina (as she was known) and Cuzzoni had appeared together in opera performances in various European cities with no trouble; there is no indication that there was any bad feeling or ill-will between the two of them prior to their London joint appearances.[2][6]

The three stars, Bordoni, Cuzzoni and Senesino commanded astronomical fees, making much more money from the opera seasons than Handel did.[7] The opera company would have been aware that the story of the two princesses in love with Alexander the Great chosen for the two prima donnas' first joint appearance was familiar to London audiences through a tragedy by Nathaniel Lee, The Rival Queens, or the Death of Alexander the Great, first performed in 1677 and often revived and it may be that they were encouraging the idea that the two singers were rivals.[6] One of the agents who had arranged Faustina's appearances in London, Owen Swiny, explicitly warned against the choice of libretto as likely to cause "disorder" in a letter to the directors of the Royal Academy of Music, imploring them:

never to consent to any thing that can put the Academy into disorder, as it must, certainly, if what I hear ... is put in Execution: I mean the opera of Alexander the great; where there is to be a Struggle between the Rival Queen's, for a Superiority.[8]

The performances of Alessandro went off with no signs of animosity between Bordoni and Cuzzoni or their respective supporters, but it was not very long after that tension between the two erupted. As 18th century musicologist Charles Burney observed about the Cuzzoni / Faustina rivalry, which became acute around the time of the performances of a subsequent Handel opera, Admeto:

it seems impossible for two singers of equal merit to tread the stage a parte eguale, as for two people to ride on the same horse, without one being behind.[9]

The Royal Academy of Music collapsed at the end of the 1728/1729 season, partly due to the huge fees paid to the star singers, and Cuzzoni and Faustina both left London for engagements in continental Europe. Handel started a new opera company with a new prima donna, Anna Strada. One of Handel's librettists, Paolo Rolli, wrote in a letter (the original is in Italian) that Handel said that Strada "sings better than the two who have left us, because one of them (Faustina) never pleased him at all and he would like to forget the other (Cuzzoni)."[10]

Roles

[edit]

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, 5 May 1726[11] |

|---|---|---|

| Alessandro | alto castrato | Francesco Bernardi, called "Senesino" |

| Rossane | soprano | Faustina Bordoni |

| Lisaura | soprano | Francesca Cuzzoni |

| Tassile | alto castrato | Antonio Baldi |

| Clito | bass | Giuseppe Maria Boschi |

| Leonato | tenor | Luigi Antinori |

| Cleone | contralto | Anna Vincenza Dotti[12] |

Synopsis

[edit]- Place: Oxidraca, India

- Time: Approx. 326 BC

Act 1

[edit]A battle is in progress with Alessandro (Alexander the Great), besieging the Indian city of Oxidraca. Despite the many victories he has won elsewhere, the city's defenders get the best of his army and he is in personal danger when he is rescued by his general Clito (Cleitus the Black), Prince of Macedonia.

In Alexander's camp, two princesses, both in love with Alessandro, are much concerned for his safety—Lisaura, a princess of Scythia, and Rossane (Roxana), a princess taken captive by Alessandro in his previous campaign in Persia. The rival princesses are tormented by jealousy for Alessandro seems unable to make up his mind which of them he prefers. The Indian King Tassile, whose life Alessandro saved and whose throne he restored, brings the glad tidings to the princesses that Alessandro is safe and unharmed. Both ladies are overjoyed at the news, which grieves Tassile, as he is hopelessly smitten with Princess Lisaura.

In the temple of Jupiter, Alessandro gives thanks for yet another glorious victory, but his apparent invincibility has gone to his head. He announces that he is a god, the son of the divine Jupiter, and orders that he shall be worshiped as such. General Clito protests at this sacrilege, enraging Alessandro, who orders Clito's execution, but he eventually yields to pleas from the princesses to show mercy.

Act 2

[edit]Alessandro, finding both princesses captivating, still cannot decide between the two of them. He encourages them both equally, which drives the ladies to distraction. Rossane, a captive, makes melting appeals to Alessandro to free her and show his magnanimity. Alessandro hesitates to do so, fearing that she will then leave him, but finally agrees to release her from her bondage.

Meanwhile, General Leonato and others of Alessandro's officers are appalled at his seeming descent into insane megalomania, and they plot to assassinate him.

In Alessandro's quarters, he announces to the assembled generals that he intends to divide the vast territories he has conquered among them and give them all away. His status as a living god to be worshiped will suffice for him. General Clito is once again compelled by his conscience to denounce such arrogance, whereupon Alessandro is about to run him through with his sword, but suddenly, as part of a plot by the conspirators, the roof caves in. Miraculously, no one is injured, which only reinforces Alessandro's conviction that he is beloved of the gods. Alessandro orders his sycophantic follower Cleone to lead Clito to jail.

Rossane has heard of the assassination attempt on Alessandro and believes it to have been successful. She weeps and mourns in despair, and Alessandro, overhearing this, is deeply touched by such devotion and decides she will be the woman of his choice. No sooner has he made this clear to her than King Tassile brings news that the people of Oxidraca, who seemed finally conquered, are staging a revolt. Alessandro rushes to battle, leaving Rossane once again anxiously praying for his safety.

Act 3

[edit]

General Leonato frees Clito from prison and throws Cleone in jail instead, but Cleone is also released by his supporters. The conspirators are now resolved to wage open warfare against their former leader, Alessandro, leading large parts of his army in a mutiny. Cleone is aware of this plot and informs Alessandro.

Alessandro, having decided to take Rossane as wife, breaks the news gently to Princess Lisaura, explaining that he is not good enough for her and that King Tassile, his dearest friend, loves her and he must not stand in the way of Tassile making Lisaura his queen. Tassile is overjoyed.

The conspirators and the mutinous army launch into battle against Alessandro, but King Tassile supports him with his troops and the conspirators are defeated. They beg for mercy, which Alessandro generously grants. Alessandro will marry Rossane, Tassile will have Lisaura, all are forgiven and praise the great hero's magnanimity.[6][13]

Musical features

[edit]After the overture, the opera begins with rousing battle music featuring trumpets and drums. Handel is very careful to give both leading ladies equal opportunities; they make their entrances simultaneously and they have an equal number of arias and one duet together.[14] Handel differentiates between the two princesses through his music; Lisaura is given melancholy and expressive music with a pensive and brooding quality, whereas the music for Rossane portrays her as scheming and spirited with some vocal writing of enormous virtuoso demands.[15] For Paul Henry Lang, Rossane's love music in act two as she waits for Alessandro is "Handel at his idyllic-pastoral best".[16]

The opera is scored for two recorders, two oboes, a bassoon, two trumpets, two horns, strings and continuo (cello, lute, harpsichord).

Reception and performance history

[edit]Alessandro was a resounding success, with a run of thirteen performances, which would have been greater had Senesino not become indisposed necessitating cancellation of more.[15] Lady Sarah Cowper complained in a letter that it was difficult to get tickets.[17] Handel revived the work in his seasons of 1727 and 1732.[12] Horace Walpole recalled years later that at the performance he saw, during the opening scene depicting the siege of Oxidraca, Senesino "So far forgot himself in the heat of the conquest, as to stick his sword into one of the pasteboard stones of the wall of the town, and bore it in triumph before him."[17]

As with all Baroque opera seria, Alessandro went unperformed for many years, but with the revival of interest in Baroque music and historically informed musical performance since the 1960s,Alessandro, like all Handel operas, receives performances at festivals and opera houses today.[18] Among other performances, Alessandro was produced at the Badisches Staatstheater Karlsruhe in 2012,[19] at the Palace of Versailles as part of the Versailles Festival in May and June 2013,[20] and at the Athens Festival also in 2013.[21]

Recordings

[edit]

| Year | Cast: Alessandro, Rossane, Lisaura, Tassile, Clito, Leonato, Cleone | Conductor, orchestra | Label |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | René Jacobs, Sophie Boulin, Isabelle Poulenard, Jean Nirouët, Stephen Varcoe, Guy de Mey, Ria Bollen | Sigiswald Kuijken, La Petite Bande | CD:Deutsche Harmonia Mundi IC 157 16 9537 3 |

| 2012 | Lawrence Zazzo, Yetzabel Arias Fernández, Raffaella Milanesi, Martin Oro, Andrew Finden, Sebastian Kohlhepp, Rebecca Raffell | Michael Form, Deutsche Händel-Solisten | CD:Pan Classics PC 10273 |

| 2012 | Max Emanuel Cenčić, Julia Lezhneva, Karina Gauvin, Xavier Sabata, Vasily Khoroshev, Juan Sancho, In-Sung Sim | George Petrou Armonia Atenea | CD:Decca Classics 4784699 |

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ King, Richard G., "Classical History and Handel's Alessandro" (February 1996). Music & Letters, 77 (1): pp. 34–63.

- ^ a b c Burrows 2012, p. 154

- ^ Levine, Robert. "Elegant, Beautifully Performed Handel". Classics Today. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ^ Dean, Winton; Knapp, John Merrill (1995). Handel's Operas 1704–1726. Boydell Press. p. 298.

- ^ Strohm, Reinhard (20 June 1985). Essays on Handel and Italian opera by Reinhard Strohm. ISBN 9780521264280. Retrieved 2 February 2013 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Beasly, Gregg. "Alessandro". handelhendrix.org. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ^ Snowman, Daniel (2010). The Gilded Stage: A Social History of Opera. Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1843544661.

- ^ Hicks, Anthony. "Programme Notes for The Rival Queens". Hyperion Records. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- ^ Dean, Winton (1997). The New Grove Handel. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0393303582.

- ^ "Lotario". handelhendrix.org. Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ^ Casaglia, Gherardo (2005). "Alessandro, 5 May 1726". L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia (in Italian).

- ^ a b "G. F. Handel's Compositions". GF Handel.org. Handel Institute. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ^ "Synopsis of Alessandro". Naxos records. Archived from the original on 17 November 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ Aspden, Susanne (2013). The Rival Sirens: Performance and Identity on Handel's Operatic Stage. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107033375.

- ^ a b Burrows, Donald (1998). The Cambridge Companion to Handel. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521456135.

- ^ Lang, Paul Henry (2011). George Frideric Handel (reprint ed.). Dover Books on Music. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-486-29227-4.

- ^ a b Dean 2006, pp. 24 ff

- ^ "Handel:A Biographical Introduction". GF Handel.org. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ^ "Alessandro". Badisches Staatstheater Karlsruhe.

- ^ "Handel Alessandro". Versailles Festival. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ "Alessandro". Athens-Epidaurus Festival. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014.

Sources

- Burrows, Donald (2012). Handel. Master Musicians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199737369.

- Dean, Winton (2006), Handel's Operas, 1726–1741, Boydell Press, ISBN 1-84383-268-2 The second of the two-volume definitive reference on the operas of Handel

External links

[edit]- Italian libretto Archived 2011-06-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Score of Alessandro (ed. Friedrich Chrysander, Leipzig 1877)

- Alessandro: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch