Adenocarcinoma in situ of the lung

| Adenocarcinoma in situ of the lung | |

|---|---|

| |

| Detail of a CT thorax showing a mixed solid and ground glass lung lesion consistent with an adenocarcinoma of the lung. | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) of the lung —previously included in the category of "bronchioloalveolar carcinoma" (BAC)—is a subtype of lung adenocarcinoma. It tends to arise in the distal bronchioles or alveoli and is defined by a non-invasive growth pattern. This small solitary tumor exhibits pure alveolar distribution (lepidic growth) and lacks any invasion of the surrounding normal lung. If completely removed by surgery, the prognosis is excellent with up to 100% 5-year survival.[1]

Although the entity of AIS was formally defined in 2011,[2] it represents a noninvasive form of pulmonary adenocarcinoma which has been recognized for some time. AIS is not considered to be an invasive tumor by pathologists, but as one form of carcinoma in situ (CIS). Like other forms of CIS, AIS may progress and become overtly invasive, exhibiting malignant, often lethal, behavior. Major surgery, either a lobectomy or a pneumonectomy, is usually required for treatment.

Causes

[edit]The genes mutated in AIS differ based on exposure to tobacco smoke. Non-smokers with AIS commonly have mutations in EGFR (a driver) or HER2 (an important oncogene), or a gene fusion with ALK or ROS1 as one of the elements.[3]

Mechanism

[edit]Nonmucinous AIS is thought to derive from a transformed cell in the distal airways and terminal respiratory units, and often shows features of club cell or Type II pneumocyte differentiation.[4] Mucinous AIS, in contrast, probably derives from a transformed glandular cell in distal bronchioles.[5]

A multi-step carcinogenesis hypothesis suggests a progression from pulmonary atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH) through AIS to invasive adenocarcinoma (AC), but to date this has not been formally demonstrated.[6]

Type-I cystic adenomatoid malformation (CAM) has recently been identified as a precursor lesion for the development of mucinous AIS, but these cases are rare.[7][8]

Rarely, AIS may develop a rhabdoid morphology due to the development of dense perinuclear inclusions.[9]

Diagnosis

[edit]The criteria for diagnosing pulmonary adenocarcinoma have changed considerably over time.[10][11] The 2011 IASLC/ATS recommendations, adopted in the 2015 WHO guidelines, use the following criteria for adenocarcinoma in situ: [12]

- tumor ≤3 cm

- solitary tumor

- pure "lepidic" growth*[13]

- No stromal, vascular, or pleural invasion

- No histologic patterns of invasive adenocarcinoma

- No spread through air spaces

- Cell type mostly nonmucinous

- Minimal/absent nuclear atypia

- ± septal widening with sclerosis/elastosis

* lepidic = (i.e. scaly covering) growth pattern along pre-existing airway structures

By this standard, AIS cannot be diagnosed according to core biopsy or cytology sampling.[2] Recommended practice is to report biopsy findings previously classified as nonmucinous BAC as adenocarcinoma with lepidic pattern, and those previously classified as mucinous BAC as mucinous adenocarcinoma.[14]

Classification

[edit]The most recent 2015 World Health Organization (WHO) and 2011 International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) / American Thoracic Society (ATS) guidelines refine pulmonary adenocarcinoma subtypes in order to correspond to advances in personalized cancer treatment.[2]

AIS is considered a pre-invasive malignant lesion that, after further mutation and progression, is thought to progress into an invasive adenocarcinoma. Therefore, it is considered a form of carcinoma in situ (CIS).

There are other classification systems that have been proposed for lung cancers. The Noguchi classification system for small adenocarcinomas has received considerable attention, particularly in Japan, but has not been nearly as widely applied and recognized as the WHO system.[15]

AIS may be further subclassified by histopathology, by which there are two major variants:

Treatment

[edit]This information is mostly in reference to the now outdated entity of BAC, which included some invasive forms of disease.

The treatment of choice in any patient with BAC is complete surgical resection, typically via lobectomy or pneumonectomy, with concurrent ipsilateral lymphadenectomy.[16]

Non-mucinous BAC are highly associated with classical EGFR mutations, and thus are often responsive to targeted chemotherapy with erlotinib and gefitinib. K-ras mutations are rare in nm-BAC.[18]

Mucinous BAC, in contrast, is much more highly associated with K-ras mutations and wild-type EGFR, and are thus usually insensitive to the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors.[19] In fact, there is some evidence that suggests that the administration of EGFR-pathway inhibitors to patients with K-ras mutated BAC may even be harmful.[20]

Prognosis

[edit]This information is mostly in reference to the now outdated entity of BAC, which included some invasive forms of disease.

Taken as a class, long-term survival rates in BAC tend to be higher than those of other forms of NSCLC.[21][22] BAC generally carries a better prognosis than other forms of NSCLC, which can be partially attributed to localized presentation of the disease.[23] Though other factors might play a role. Prognosis of BAC depends upon the histological subtype and extent at presentation but are generally same as other NSCLC.[24]

Recent research has made it clear that nonmucinous and mucinous BAC are very different types of lung cancer.[4][25] Mucinous BACis much more likely to present with multiple unilateral tumors and/or in a unilateral or bilateral pneumonic form than nonmucinous AIS .[4] The overall prognosis for patients with mucinous AIS is significantly worse than patients with nonmucinous AIS .[26][27]

Although data are scarce, some studies suggest that survival rates are even lower in the mixed mucinous/non-mucinous variant than in the monophasic forms.[27]

In non-mucinous BAC, neither club cell nor type II pneumocyte differentiation appears to affect survival or prognosis.[4]

Recurrence

[edit]When BAC recurs after surgery, the recurrences are local in about three-quarters of cases, a rate higher than other forms of NSCLC, which tends to recur distantly.[16]

Epidemiology

[edit]Information about the epidemiology of AIS is limited, due to changes in definition of this disease and separation from BAC category.

Under the new, more restrictive WHO criteria for lung cancer classification, AIS is now diagnosed much less frequently than it was in the past.[28] Recent studies suggest that AIS comprises between 3% and 5% of all lung carcinomas in the U.S.[26][23]

Incidence

[edit]The incidence of bronchiolo-alveolar carcinoma has been reported to vary from 4–24% of all lung cancer patients.[23] An analysis of Surveillance epidemiology and End results registry ( SEER) by Read et al. revealed that although the incidence of BAC has increased over the past two decade it still constitutes less than 4% of NSCLC in every time interval.[23] This difference in the incidence has been attributed to complex histopathology of cancer. While pure BAC is rare, the increase in incidence as seen in various studies can be due to unclear histological classification till WHO came up with its classification in 1999 and then in 2004. Another distinguishing feature about BAC is that it afflicts men and women in equal proportions, some recent studies even suggest slightly higher incidence among women.[26][23]

History

[edit]The criteria for classifying lung cancer have changed considerably over time, becoming progressively more restrictive.[12][2]

In 2011, the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification recommended discontinuing the BAC classification altogether, as well as the category of mixed subtype adenocarcinoma. This change was made because the term BAC was being broadly applied to small solitary noninvasive tumors, minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, mixed subtype invasive adenocarcinoma, and even widespread disease.[14] In addition to creating the new AIS and minimally-invasive categories, the guidelines recommend new terminology to clearly denote predominantly-noninvasive adenocarcinoma with mild invasion (lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma), as well as invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma in place of mucinous BAC.[14]

Additional images

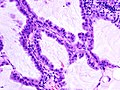

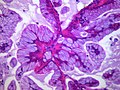

[edit]Mucinous BAC

Non-mucinous BAC

See also

[edit]- Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia of the lung

- Minimally invasive adenocarcinoma of the lung

- Adenocarcinoma of the lung

References

[edit]- ^ Van Schil, P. E.; Asamura, H; Rusch, V. W.; Mitsudomi, T; Tsuboi, M; Brambilla, E; Travis, W. D. (2012). "Surgical implications of the new IASLC/ATS/ERS adenocarcinoma classification". European Respiratory Journal. 39 (2): 478–86. doi:10.1183/09031936.00027511. PMID 21828029. S2CID 15709782.

- ^ a b c d Travis, William D.; Brambilla, Elisabeth; Nicholson, Andrew G.; Yatabe, Yasushi; Austin, John H.M.; Beasley, Mary Beth; Chirieac, Lucian. R.; Dacic, Sanja; Duhig, Edwina (2015). "The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Lung Tumors". Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 10 (9): 1243–1260. doi:10.1097/jto.0000000000000630. PMID 26291008.

- ^ World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 5.1. ISBN 978-9283204299.

- ^ a b c d e Yousem SA, Beasley MB (July 2007). "Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma: a review of current concepts and evolving issues". Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 131 (7): 1027–32. doi:10.5858/2007-131-1027-BCAROC. PMID 17616987.

- ^ Chilosi M, Murer B (January 2010). "Mixed adenocarcinomas of the lung: place in new proposals in classification, mandatory for target therapy". Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 134 (1): 55–65. doi:10.5858/134.1.55. PMID 20073606.

- ^ Bettio, D; Cariboni, U; Venci, A; Valente, M; Spaggiari, P; Alloisio, M (2012). "Cytogenetic findings in lung cancer that illuminate its biological history from adenomatous hyperplasia to bronchioalveolar carcinoma to adenocarcinoma: A case report". Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 4 (6): 1032–1034. doi:10.3892/etm.2012.725. PMC 3494121. PMID 23226769.

- ^ Scialpi M, Cappabianca S, Rotondo A, et al. (June 2010). "Pulmonary congenital cystic disease in adults. Spiral computed tomography findings with pathologic correlation and management". Radiol Med. 115 (4): 539–50. doi:10.1007/s11547-010-0467-6. PMID 20058095. S2CID 7308576.

- ^ Abecasis F, Gomes Ferreira M, Oliveira A, Vaz Velho H (2008). "[Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma associated with congenital pulmonary airway malformation in an asymptomatic adolescent]". Rev Port Pneumol (in Portuguese). 14 (2): 285–90. doi:10.1016/S0873-2159(15)30236-1. PMID 18363023.

- ^ Song DE, Jang SJ, Black J, Ro JY (September 2007). "Mucinous bronchioloalveolar carcinoma of lung with a rhabdoid component—report of a case and review of the literature". Histopathology. 51 (3): 427–30. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02784.x. PMID 17727492. S2CID 29727857.

- ^ Kreyberg, L.; Liebow, A.A.; Uehlinger, E.A.; World Health Organization. (1967). Histological Typing of Lung Tumours. International histological classification of tumours, no. 1 (1st ed.). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. OCLC 461784.

- ^ World Health Organization (1981). Histological Typing of Lung Tumours. International histological classification of tumours, no. 1 (2nd ed.). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-176101-7. OCLC 476258805.

- ^ a b Travis, W.D.; Colby, T.V.; Corrin, B.; et al.Histological Typing of Lung and Pleural Tumors. International histological classification of tumours, no. 1 (3rd ed.). Berlin: Springer. 1999. ISBN 978-3-540-65219-9.

- ^ Iwata, H (September 2016). "Adenocarcinoma containing lepidic growth". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 8 (9): E1050 – E1052. doi:10.21037/jtd.2016.08.78. PMC 5059295. PMID 27747060.

- ^ a b c Travis; et al. (2011). "IASLC/ATS/ERS International Multidisciplinary Classification of Lung Adenocarcinoma (2011)" (PDF). www.thoracic.org. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- ^ Noguchi M, Morikawa A, Kawasaki M, et al. (June 1995). "Small adenocarcinoma of the lung. Histologic characteristics and prognosis". Cancer. 75 (12): 2844–52. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19950615)75:12<2844::aid-cncr2820751209>3.0.co;2-#. PMID 7773933. S2CID 196359177.

- ^ a b c d Raz DJ, He B, Rosell R, Jablons DM (June 2006). "Current concepts in bronchioloalveolar carcinoma biology". Clin. Cancer Res. 12 (12): 3698–704. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0457. PMID 16778095. S2CID 17340788.

- ^ Lee KS, Kim Y, Han J, Ko EJ, Park CK, Primack SL (1 November 1997). "Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma: clinical, histopathologic, and radiologic findings". Radiographics. 17 (6): 1345–57. doi:10.1148/radiographics.17.6.9397450. PMID 9397450.

- ^ Finberg KE, Sequist LV, Joshi VA, et al. (July 2007). "Mucinous differentiation correlates with absence of EGFR mutation and presence of KRAS mutation in lung adenocarcinomas with bronchioloalveolar features". J Mol Diagn. 9 (3): 320–6. doi:10.2353/jmoldx.2007.060182. PMC 1899415. PMID 17591931.

- ^ Sakuma Y, Matsukuma S, Yoshihara M, et al. (July 2007). "Distinctive evaluation of nonmucinous and mucinous subtypes of bronchioloalveolar carcinomas in EGFR and K-ras gene-mutation analyses for Japanese lung adenocarcinomas: confirmation of the correlations with histologic subtypes and gene mutations". Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 128 (1): 100–8. doi:10.1309/WVXFGAFLAUX48DU6. PMID 17580276.

- ^ Vincent MD (August 2009). "Optimizing the management of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a personal view". Curr Oncol. 16 (4): 9–21. doi:10.3747/co.v16i4.465. PMC 2722061. PMID 19672420.

- ^ Breathnach OS, Kwiatkowski DJ, Finkelstein DM, et al. (January 2001). "Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma of the lung: recurrences and survival in patients with stage I disease". J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 121 (1): 42–7. doi:10.1067/mtc.2001.110190. PMID 11135158.

- ^ Grover FL, Piantadosi S (June 1989). "Recurrence and survival following resection of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma of the lung--The Lung Cancer Study Group experience". Ann. Surg. 209 (6): 779–90. doi:10.1097/00000658-198906000-00016. PMC 1494125. PMID 2543339.

- ^ a b c d e Read WL, Page NC, Tierney RM, Piccirillo JF, Govindan R (August 2004). "The epidemiology of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma over the past two decades: analysis of the SEER database". Lung Cancer. 45 (2): 137–42. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.01.019. PMID 15246183.

- ^ Barkley, JE; Green, MR (August 1996). "Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 14 (8): 2377–86. doi:10.1200/jco.1996.14.8.2377. PMID 8708731.

- ^ Garfield DH, Cadranel J, West HL (January 2008). "Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma: the case for two diseases". Clin Lung Cancer. 9 (1): 24–9. doi:10.3816/CLC.2008.n.004. PMID 18282354.

- ^ a b c Zell JA, Ou SH, Ziogas A, Anton-Culver H (November 2005). "Epidemiology of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma: improvement in survival after release of the 1999 WHO classification of lung tumors". J. Clin. Oncol. 23 (33): 8396–405. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.03.0312. PMID 16293870. S2CID 32004708.

- ^ a b Furák J, Troján I, Szoke T, et al. (May 2003). "Bronchioloalveolar lung cancer: occurrence, surgical treatment and survival". Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 23 (5): 818–23. doi:10.1016/s1010-7940(03)00084-8. PMID 12754039.

- ^ Travis, William D; Brambilla, Elisabeth; Muller-Hermelink, H Konrad; Harris, Curtis C, eds. (2004). Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart (PDF). World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press. ISBN 978-92-832-2418-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-08-23. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch