Ancient history of the Negev

The Negev region, situated in the southern part of present-day Israel, has a long and varied history that spans thousands of years. Despite being predominantly a semi-desert or desert, it has historically almost continually been used as farmland, pastureland, and an economically significant transit area.

The ancient history of the Negev includes periods of Egyptian and Nabataean dominance, the rise of local cultures such as the Edomites, and notable agricultural and architectural developments during the Byzantine and early Islamic eras.

Historical regions of the Negev

[edit]

For historical purposes, the Negev can roughly be divided into four subregions:[1]

- The biblical Negev (yellow), referring to the small, semi-arid northeastern Arad-Beersheba Valley. Only this area is referred to as the "Negev" in the Bible, as according to biblical historiography, the holdings of the Judeans in the Negev were confined to this region.[1]

- The northern Negev (green). In biblical times, it was inhabited by the Philistines and from the 6th century B.C. by Idumeans and the so-called "Post-Philistines," whose ethnic identity remains a matter of debate. This region is also predominantly semi-desert, but it was already intensively used for agriculture during biblical times and developed, especially in the post-biblical period, into one of the most important agricultural regions of Palestine. The northern boundary is indistinct[2] and defined differently by various scholars across disciplines. The border shown on the map corresponds to the Ottoman Beersheba District, which is both one of the northernmost and one of the most commonly used boundaries in historical accounts.

- The central Negev (orange) is even drier; in the Bible, this area was therefore called the "Desert of Zin". In the northwest, it mainly consists of sand dunes;[3][4][5] the rest is predominantly composed of the Negev Highlands, which, as recent research suggests, were probably called "Mount Seir" in the Bible,[6][7][8][9][10][11] previously thought to be located east of the Jordan River.

- Finally, the southern Negev (red) has no special name in the Bible. It is the driest region of Palestine, with consistently less than 100 mm of rainfall per year. Originally, it was important mainly for its mineral resources, but starting from the time of the Nabateans, it was also used for agriculture.

The Negev region in the Bible

[edit]The Bible contains several traditions regarding the Beersheba-Arad Valley and the Negev Highlands, which can be broadly categorized into two groups. From the first group, older biblical scholarship inferred that the Negev was inhabited by the ancient Israelites during biblical times. According to the second group, a different people lived here; this group aligns more with the findings of more recent archaeology (see below).

(1) According to the Book of Genesis, already Abraham lived for a while in the central and biblical Negev after being banished from Egypt.[12] Notably, he spent a brief period living in Kadesh [Barnea][13] and later resided as a guest in Beersheba, which at that time was purportedly part of the kingdom of the Philistine king of Gerar.[14] (2) Accordingly, Numbers 34:1–7 and Joshua 15:1–3[15] are generally understood to mean that the biblical and central Negev actually belonged to God's Promised Land at least down to Kadesh Barnea at the southwestern fringes of the central Negev (but see below). This area is assigned to the Tribe of Judah[16] along with other more northerly areas. Simultaneously, the biblical and central Negev is assigned elsewhere to the Tribe of Simeon within the territory of the tribe of Judah.[17] (3) Hence, when the Israelites came from Egypt to Israel, according to Numbers 20:1–21:3,[18] only Aaron is not allowed to enter this land because he has sinned — the rest of the Israelites, however, can conquer the area.

(4) Conversely, according to Deuteronomy 1–2,[19] the area is revoked from the Israelites by God because everyone has sinned and God has also destined the land for the Edomites.[20] (5) The background for this is found in Genesis 32:3; 33:12–16,[21] where it is not Jacob, the ancestor of the Israelites, who lives there, but his brother Esau, the ancestor of the Edomites. These two grandsons of Abraham divide the promised land between them in Genesis 36:6–8[22] so that this "Edomite land" will continue to be inhabited by Edomites. (6) According to the Books of Kings, the Edomites also live here. They are sometimes ruled by Israelite kings, as the Negev was purportedly part of the kingdom of the legendary king Solomon (in its entirety, all the way to the Red Sea),[23] and from the 9th century, with varied extension to the south, part of the Kingdom of Judah.[24] But the Edomites fight against them multiple times and regain their freedom.[25][26] (7) The most common expression used in the Bible to refer to Israel as a whole is "from Dan to Beersheba." Once again, this excludes at least the central and southern Negev regions from "Israel". (8) Accordingly, it is not at all certain whether the border descriptions in Numbers 34 and Joshua 15 really include the Negev as part of the promised land, as Numbers 34 also presupposes an area of Edom west of the Jordan (which, according to Numbers 20:14-16,[27] begins at Kadesh as one of its southernmost locations). For that reason, it has recently occasionally been suggested that "Your southern border shall be from the Wilderness of Zin along the border of Edom" (Numbers 34:3) is to be understood as excluding the territory of the Edomites, and therefore at least the central and southern Negev, from the Promised Land.[28][29] However, as of yet, this is still a minority opinion.

Bronze Age and early Iron Age: The copper miners of the Negev Highlands

[edit]Bronze Age and early Iron Age: Regional History

[edit]

According to Egyptian written records, during the Bronze Age (up to the 13th century BCE) and the early Iron Age, it was the Shasu nomads who lived in the Negev and the Sinai Peninsula under Egyptian rule.[30][6][31][32] Since these are referred to, among others, as the "tribes of the Shasu of Edom," it is assumed that from this ethnic group, the Edomites emerged later, and subsequently, the Idumeans (see below).

The Egyptians operated a copper mine in the Timna Valley, as evidenced by a Hathor temple from that period.[33] After the Egyptians withdrew, another group took over the copper mine. This group also constructed a fortress-like road station at the Yotvata oasis, notably using the casemate building technique,[34][35] and established another copper mine at Khirbet en-Nahas.[36]

In the Beersheba–Arad Valley, a complex of several casemate buildings also emerged in the 12th century BCE, known as Tel Masos,[37][38] the region's first capital (until it was replaced by nearby Tel Malhata as the new capital from the 10th to the 8th century BCE.[39][40]). From Tel Masos and Yotvata, this architectural style spread throughout the Negev region between the 11th to 8th centuries BCE, with sites like Tel Esdar, Khirbet en-Nahas, Beersheba and Arad adopting similar structures. Additionally, during this time, many more farms, known as "haserim" ("enclosed homesteads"), developed, especially along the streams and brooks up to the vicinity of the Philistine locations Nahal Patish and Tell el-Far'ah (South). Gazit notes that there were 36 Haserim of at least 0.25 hectares in size in the 11th century alone in the region, along with many smaller farms.[41] Moreover, in the same period, about 60 small casemate buildings appeared in the Negev Highlands.[42] Many of these sites also had additional smaller buildings, totaling several hundred.[43][44][45][46] These settlements were likely involved in operating the copper mines, which is supported by the presence of copper slags from the Arabah in Negevite pottery.[47][48][49][50][51][52][53]

These archaeological finds are primarily interpreted in two different ways. Initially, biblical archaeologists interpreted the casemate buildings in the highlands as the garrisons mentioned in 2 Samuel 8:14, which states that King David built garrisons "throughout all Edom",[54] which is why they are still referred to as "fortresses" today.[52] This interpretation was gradually abandoned in the early 1990s:[55] Archaeologists, noting that Yotvata, Tel Masos, and the copper mines were built and operated more than 100 years before David's time, emphasizing that the buildings in the Negev were clearly no "fortresses," and showcasing distinct architectural styles and ceramics different from those in the Judean settlement area, proposed alternative theories. They suggested that either the ancestors of the Edomites built the Negev localities and operated the copper mines, governed by the "Tel Masos chiefdom",[56][57][58][59][60] or that alongside these nomadic people, a third, unknown sedentary people also lived there, with one of these two groups controlling the copper mines.[61][62][63][64] However, in 2023, Tali Erickson-Gini once again advocated the older "Israel hypothesis," claiming that this interpretation had been consciously "swept under the rug" by archaeologists.[65]

Bronze Age and early Iron Age: Agricultural History

[edit]

| External images | |

|---|---|

The high number of Early Iron Age buildings in the Negev Highlands, with surveys identifying nearly 450 in total,[69] is surprising given the area's low rainfall, typically less than 200 mm/year.[70] However, the Negevites appear to have developed innovative agricultural techniques to cope with these conditions:

- They built their buildings near the small wadis of the Negev Highlands, where they carved cisterns into the rock to capture and store winter rainwater.[71]

- They also constructed terraced fields along these wadis, designed to channel flowing water from the wadis and running water from the wadi slopes to plants and slow drainage, thus maximizing moisture retention and minimizing soil erosion.[72]

Michael Evenari demonstrated at his experimental Avdat farm that this farming method could successfully grow even grapes with less than 100 mm/year of rainfall.[73]

However, interpretations differ regarding the timing of terrace construction. It is clear that the majority of the millions[74] of wadi terraces still found in the Negev today originated in the Byzantine and Early Islamic periods[75][76][77] (see below). However, excavated blades, silos and threshing floors from the Iron Age,[78][79] along with new Radiocarbon[80] and OSL datings,[81][82] suggest that some terraces were built as early as the Iron Age or even earlier.[83][84][85][86]

Conversely, research teams led by Israel Finkelstein investigated ancient dung heaps in the Negev mountains and at the Timna mines and discovered that in the central Negev, small livestock primarily grazed on wild-growing winter and spring plants,[87][88][89] while in the Timna area, they were mainly fed hay and grape pomace.[90][89] Accordingly, they suggest that the practice of crop cultivation in the Negev mountains during the rainy season might have started later. If this is accurate, the Iron Age Negevites likely lived in the Negev mountains during the rainy season, practicing only livestock farming there. During the summer, they moved south to mine copper and imported grain and grape pomace from the Philistines and Judeans in the north. If one accepts the early dating of the agricultural terraces instead, it appears that Negevite society was structured such that they lived in the Negev mountains during the rainy season, engaging in crop and vine cultivation to stockpile supplies. During the summer, they moved down to the copper mines, mined copper, and fed their animals with the stored hay and grape pomace.

Later Iron Age: Regional and economic history

[edit]The political situation of the Negevites and their neighboring peoples as well as territorial fluctuations at this time largely depended on the surrounding political superpowers:

- Following Hazael's conquest of the region of Palestine in the 9th century, the Judeans in the north grew stronger[91] and expanded into the Beersheba-Arad Valley, as indicated by ceramics found in Arad and Aroer[92] and ostraca found in Arad.[93]

- The subsequent conquest of Palestine by the Assyrians in the 8th century brought a political and economic upswing for the Negevites (like the Philistines and in contrast to the Judeans). They expanded further east in the Beersheba-Arad Valley, beyond the borders shown on the map above, to places such as Horvat Qitmit, Horvat Uza, Horvat Radum, Mizpe Zohar, and the Gorer Tower.[94][95][96][97]

- However, it was the conquest of Palestine by the Babylonians in the 6th century BCE that had the most significant impact on regional history. The Judean region north of the Negevites was almost completely destroyed, after which the Negevites advanced north into the more fertile Central Palestine. It is likely this invasion that the pronounced hatred for "Edom" in the later biblical texts originates from.[98][99][100][101] This regional situation remained for the next few centuries: According to Diodorus Siculus and Josephus, even in the 1st century BCE and CE, the border between Judea and the Negevites ("Idumaea") was at the same level, namely "between Beth-zur and Hebron" or "near Gaza."[102][103]

The economic background of this relocation appears to have been that deforestation had made further copper mining impossible: From the 12th to the 9th century BCE, copper mining was gradually intensified to such an extent that by the 9th century, a total of 460 tons per year were being extracted solely at Khirbet en-Nahas.[104] This, however, led to an overexploitation of natural resources, which eventually brought copper production to a complete halt, as indicated by the analysis of charcoal remains.[105][106][107]

Following the decline of copper mining, the Negevites appear to have increasingly focused on trade to the east. Camels seem to have been regularly used for trade starting from this period, as excavated camel and dromedary bones from the late 10th and early 9th centuries BCE suggest.[108][109] It was also only from this time on that they expanded to the east of the Jordan river and founded Bozra and subsequently other towns along the King's Highway, which until recently were considered the "core territory" of Edom.[110][111][112][113][114][115] The pottery found in these areas suggests that the same ethnic groups lived here as in the central Negev and (temporarily alongside Judeans[116][117][118][119][120]) in the Beersheba-Arad Valley. Thus, when the Edomites relocated to Central Palestine, they left the Negev; subsequent survey results show that only 11 sites can be identified in the highlands from the following period[69] (see below).

Hellenistic period: Nabataeans

[edit]Early Nabataean period: Regional history

[edit]

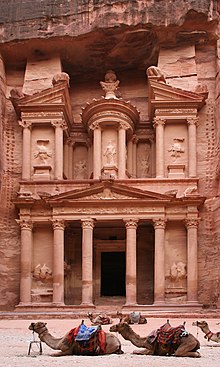

Soon after, also the Idumeans living in ancient Edom east of the Jordan river were displaced by invading Arabian Qedarites and moved to join their kin in southern Judah. Subsequently, sometime between the late 4th and early 2nd century BC, these Qedarites were themselves pushed northwestward by the invading Nabateans.[121][122] As a result, the Idumeans and Qedarites intermingled in southern Judah,[123] while the Nabateans settled in the former territories of Edom east of the river Jordan, the Negev, and Sinai,[124][125][126][127] taking control of these areas and the ancient trade routes.[128] They established the so-called "desert towns" located along the Negev incense route at Avdat, Mampsis, Rehovot, Shivta, Nessana, and especially Elusa, which was to become the new capital and the only polis of the Negev.[129]

Early Nabataean period: Agricultural history

[edit]Previously, it was believed that the early Nabateans were responsible for the terraced fields in the Negev Highlands,[130] but archaeological evidence does not support this claim.[131][132] Instead, the Nabateans are rightly famous for two other innovations in the arid desert landscape. First, they developed characteristic arched cisterns. More importantly, second, they constructed long water channels[133] from perennial springs to their cities and villages (as in En Erga, En Ziq, and Qasr Ruheibeh in the central Negev, and En Rahel and Moyat Awad in the Arabah), which functioned in their early time mainly not as agricultural farms but as caravan stops and trade stations.[134]

Maccabean period: Regional history

[edit]Josephus reports that the Maccabees conquered the Idumean border towns of Maresha and Adoraim and gave the Idumaeans a choice: either be circumcised and adopt Jewish customs or leave the area.[135][136] Some historians believe that events unfolded largely as Josephus describes: The Hasmoneans invaded Idumaea, conquered many towns, and forcibly converted the Idumaeans, who reluctantly accepted this conversion "out of attachment to their homeland."[137][138][139]

| External image | |

|---|---|

However, recent archaeological investigations have revealed (1) that Hasmonean conquests can be traced in only a few locations along the northern border of Idumaea (such as Khirbet er-Rasm,[141] possibly Maresha[142] and Lachish[143]). In contrast, the vast majority of Idumaean settlements were abandoned without signs of conflict,[144][145][146] remained abandoned for some time, and were later resettled by the same population group after the Hasmonean period. (2) Archaeologically, it does not appear that the Judeans forced the Idumaeans to undergo circumcision or to adopt "Jewish customs." The Idumaeans were already practicing circumcision,[147] and other practices that later came to be seen as "Jewish" — such as ritual purification in mikvaot, ritual purification of vessels, specific burial customs, and avoidance of pork — appear to have been observed by the Idumaeans before they were by the Judeans. As a result, it is now occasionally suggested that, conversely, the Judeans may have adopted Idumaean customs.[148][149] (3) Both a report by Josephus about the Qos-priest Costobarus and the discovery of a Herodian Qos sanctuary at Mamre suggest that the returning Idumaeans continued practicing their traditional religion nearly 100 years after their supposed conversion.[150][151][152][153][154]

Contrary to Josephus' account, it is now more frequently suggested — based on the archaeological evidence — that many Idumaeans left their homeland for still unexplained reasons in the 2nd century BCE, that those who remained voluntarily entered into an alliance with the Judeans, and that both the remaining and returning Idumaeans continued practicing their traditional religion.[155][156][157] The reports of forced conversions may have been either anti-Hasmonean propaganda[158] Hasmonean propaganda,[159] or more etiological than historical, intended to explain why the Idumaeans and Judeans shared similar customs.[160]

According to the Books of the Maccabees and Josephus, the Maccabees did not advance into the central and southern Negev. Hence, archaeological excavations in these areas reveal that the Nabataean religion was practiced there without interruption until the beginning of the Islamic period in the 7th century.[161] Nabatean political control of the Negev only ended when the Roman empire annexed their lands in 106 CE.

Byzantine and early Islamic Period

[edit]Byzantine period: Regional history

[edit]In the 4th century, Byzantine rule introduced Christianity to the region. Combined with a stable political climate,[162] this led to a significant population growth throughout the entire region. Immigrating Christians predominantly settled in the area of today's West Bank down to the Beersheba Valley, which had been most thoroughly extensively cleared of Judeans by the Romans. In the Beersheba Valley alone, the number of settlements surged from 47 in the Roman period (up to the 4th century) to 321 during the Byzantine era (4th - early 7th centuries); Beersheba expanded to an area of 90–140 ha,[163] making it even larger than nearby Gaza and Anthedon, each covering about 90 ha.[164]

Byzantine period: Agricultural history

[edit]

Iron Age: Era of the copper miners.

Persian Period: Copper miners relocate to Judaea.

Hellenistic/Roman: Nabataeans migrate to the Negev Highlands.

Byzantine/Early Islamic: Christian settlement wave and Arab expansion.

One of the three additional clusters of Christian settlements were the Nabatean desert towns.[166] Most of these evolved into large agricultural villages with many smaller farms and villages around them.[167] Ultimately, the whole central Negev, extending down roughly to the Ramon Crater, was dotted with hundreds of small agricultural villages and farms. These were likely operated by Nabataeans assimilated to the Byzantine Empire,[168][169] after Nabatean trade had declined starting from late Roman times.[122] On the character of Byzantine (and early Islamic) agriculture in the Negev, see below.

Early Islamic period: Regional History

[edit]From 602 to 628, the Byzantine military was severely depleted during the Byzantine-Sassanian War and regained control over Palestine only with great difficulty. After that, despite forming alliances with several Bedouin tribes, such as the Banu Amilah, the Banu Ghassan, the Banu Judham, and the Banu Lakhm, who were migrating from the Arabian Peninsula to the southern Negev during this period,[170] the Arab forces encountered little resistance in their Islamic expansion into Palestine beginning in AD 634. By around AD 636, with the decisive Battle of the Yarmuk, the war was largely decided.

As mostly in the rest of the region of Palestine, the Islamic expansion left no archaeological trace in the Negev:[171][172]

[...N]ot even one of the Negev towns was affected by the Islamic conquest. No hint of a violent invasion or destruction, or even a slight change in the material culture is found in the large-scale excavations of the sites. The archaeological findings point to an uninterrupted pattern of settlement which continued from the Byzantine period into the later stages of the early Islamic period.

— Gideon Avni, 2008[173]

| External image | |

|---|---|

There are also no clear signs of religious wars and forced conversions. In Nessana, it even appears that the same building was used simultaneously as both a church and a mosque. Similarly, in Nahal Oded (on the southwestern slope of the Ramon Crater), the same building seems to have served as a pagan cult place and a mosque at the same time.[175] Related to this phenomenon is the fact that the early Palestinian Muslims even integrated the Christian festivals of Easter, Pentecost, Christmas, and Saint Barbara into the Muslim calendar.[176] Therefore, on the eve of the Crusades, Palestine was still predominantly Christian.[177] Hence, Ibn al-Arabi, who visited Palestine at the end of the 11th century, could still write: "The country is theirs [the Christians'] because it is they who work its soil, nurture its monasteries and maintain its churches."[176]

Early Islamic period: Ruralization

[edit]The Arabic invasion, however, accelerated a trend toward deurbanization and ruralization, especially in the Negev, which had already started in Byzantine times, to which a number of factors contributed:

- By the end of the Byzantine period, Christianity had become widespread in Palestine; however, within Christianity, the characteristic aspects of Roman-Byzantine urban culture were viewed as promoting unchristian frivolity. Consequently, urban institutions such as Roman baths and theaters began to be dismantled or destroyed from this time onward, reducing the appeal and hence the pull factors of cities.[178][179][180]

- Many monks, whose monasteries often served as the Christian centers of smaller towns (as in Avdat and Nessana[181]), left Palestine after the Arab invasion, diminishing another pull factor of these towns.[182]

- A drought during the Late Antique Little Ice Age in the early sixth century, the Plague of Justinian that broke out in the densely populated cities of southern Palestine in the mid-sixth century, and a severe earthquake in the Negev toward the start of the early Islamic period drove urban populations to the countryside, where they now had to fend for themselves.[183][184][185]

- In Southern Palestine, a new economic sector emerged due to the strong international demand for "Gaza wine," which was primarily produced in Yavneh, Ashkelon, and Gaza.[186] To capitalize on this, some inhabitants of the Negev towns took up viticulture in the countryside.[169][187][188][185] Viticulture reached its peak between the 5th and early 7th centuries with the dramatic drop after 700.[189] Even Arab writers of the Umayyad period praised the quality of Palestinian wine.[190] After the wine trade collapsed, it seems that the vineyards were instead continued to be used for olive cultivation.[191]

- The Arab conquest and the Muslim imposition of two new taxes called Jizya and Kharaj on non-Muslims and non-Bedouins led to the cessation of the flow of Christian immigrants. The absence of Christian pilgrims also dried up financial flows,[192] prompting even more Palestinians to turn back to subsistence farming.

Already in the Byzantine period, 90% of the settlements in the Negev were agricultural farms and villages. Following the decline of the towns during the early Islamic period, the total number of settlements gradually decreased,[nb 1] yet the proportion of agricultural villages among these settlements further increased. According to Rosen, this shift of life from cities to rural areas is the reason why most Byzantine churches are found in the desert towns, whereas most early mosques are found in rural areas.[197] Also, further to the south, around the Ramon Crater at the southern fringes of the Negev highlands, the Negev Bedouin replicated the northern terrace architecture.[198] Haiman estimates that during the early Islamic period, there would have been about 300 individual farming villages, each with 80–100 residents, cultivating a total of approximately 6,500 hectares of agricultural land (nearly 3% of the total area of the Negev Highlands).[199] Newer surveys suggest that they might have cultivated even up to 30,000 – 50,000 hectares, which would correspond to nearly 14 – 23% of the area.[200][201]

Meanwhile, the desert towns gradually died a quiet death: Elusa collapsed already towards the end of the Byzantine period, likely due to the Justinianic Plague and the Late Antique Little Ice Age.[202] Mampsis was abandoned either by the 7th or 8th century, Rehovot by the 8th century. The abandonment of Avdat, seemingly due to an earthquake,[203][204] is now also dated to the 8th century.[205] The archaeologically poorly preserved Beersheba and its surroundings, including the revitalized towns Tel Masos, Tel Malhata and Tel Ira, may also have been abandoned by the 8th or 9th century. However, Shivta, Nessana, and the large Khirbet Futais (in the area of the former Philistine Nahal Patish) continued to exist at least until the 10th century. In Ayla, where the new inhabitants of the region resumed mining copper and started to mine gold, there can even be observed further growth; the towns were only abandoned in the 11th century.[206][207][192][208]

From the 12th century onwards, as the Crusaders and then the Mamluks ravaged central and northern Palestine, most of the villagers and townspeople of the Negev had already migrated to these regions or to Europe. This, the war waged by the Crusaders against Southern Palestine as well, and the (not certain but likely) fact that the Mamluks prohibited permanent settlements in the Negev, led to the transformation of the Negev into a region inhabited solely by semi-nomadic and predominantly Muslim Bedouins.[209]

Byzantine and early Islamic desert agriculture

[edit]| External image | |

|---|---|

If agriculture was already practiced on terraces during the Iron Age, this system was certainly further developed from the Byzantine period onwards:

- Starting in the Byzantine period, the Negevites stacked stone heaps, called Tuleilat el-Anab ("grape mounds"),[211] to better facilitate the flow of rainwater into the wadis[212] and probably also to reduce evaporation in the soil beneath these heaps for growing grape vines.[nb 2]

- They also constructed artificial dovecotes alongside the terraces, so that the pigeons could fertilize the agriculturally used soil with their droppings.[216][217][218]

- Finally, the most sophisticated irrigation system originates from the early Islamic period: The inhabitants of the arid area around Yotvata in the southern Negev constructed tunnel systems known as "qanat," spanning several kilometers. These tunnels served as irrigation channels, directly connecting groundwater reservoirs to agricultural fields covering several hundred hectares.[219][220][221] Uzi Avner writes that according to radiocarbon data, after the destruction of Ayla in the 11th century, "only small-scale cultivation was continued by Bedouins;"[222] however, he does not specify how this "only small-scale" cultivation is identified. New research suggests instead that agriculture near Eilat was later expanded, as several excavated terraces are of a younger age: The oldest terrace dated post-11th century was constructed between the 14th and 16th centuries, with the next one built in the 16th century, followed by several more in the 17th and 18th centuries.[223]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The exact figure is uncertain and controversial. For instance, Michael cites 101 sites in the Beersheba area as definitely inhabited during the Early Islamic period, compared to 47 in the Roman period and 321 during the Byzantine era. However, given that many settlements traditionally classified as "Byzantine" were also inhabited during the early Islamic period,[193][194][195] she suggests that their number was "probably (much) higher than registered".[196]

- ^ Evenari strongly argued against the second purpose of the "grape mounds". However, Boyko discovered remnants of grapevines within the mounds, which seems to support this intended function as well.[213][214][215]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Detlef Jericke (2011). "Negev". WiBiLex.

- ^ "Negev". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2024-07-01.

- ^ Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry (1946). A Survey of Palestine. Prepared in December 1945 and January 1946 (PDF). The Government Printer, Palestine. p. 370.

A considerable part of this comparatively fertile zone is covered by a block of shifting sand. Excavation has shown that there was already sand at Khalasa in the third to the fourth century A.D.

- ^ Survey of Palestine 1:100,000 map.

- ^ Khalid Fathi Ubeid (2014). "Sand dunes of the Gaza Strip (Southwestern Palestine): Morphology, textural characteristics and associated environmental impacts". Earth Sciences Research Journal. 18 (2): 138.

- ^ a b Uzi Avner (2021). "The Desert's Role in the Formation of Early Israel and the Origin of Yahweh". Entangled Religions. 12 (2): 23, 27.

- ^ John R. Bartlett (1969). "The Land of Seir and the Brotherhood of Edom". Journal of Theological Studies. 20 (1): 1–20.

- ^ Laura M. Zucconi (2007). "From the Wilderness of Zin alongside Edom: Edomite Territory in the Eastern Negev during the Eighth-Sixth Centuries B.C.E.". In Sarah Malena / David Miano (ed.). Milk and Honey. Essays on Ancient Israel and the Bible in Appreciation of the Judaic Studies Program at the University of California. Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 250.

- ^ Jason C. Dykehouse (2008). An Historical Reconstruction of Edomite Treaty Betrayal in the Sixth Century B.C.E. Based on Biblical, Epigraphic, and Archaeological Data (Thesis). p. 54.

- ^ Benedikt Hensel (2022). "Edom and Idumea in the Persian Period: An Introduction to the Volume" (PDF). In Idem (ed.). About Edom and Idumea in the Persian Period. Recent Research and Approaches from Archaeology, Hebrew Bible Studies and Ancient Near Eastern Studies. Equinox Publishing. p. 2.

- ^ Erez Ben-Yosef (2023). "A False Contrast? On the Possibility of an Early Iron Age Nomadic Monarchy in the Arabah (Early Edom) and Its Implications for the Study of Ancient Israel". In Ido Koch (ed.). From Nomadism to Monarchy? Revisiting the Early Iron Age Southern Levant. Eisenbrauns. p. 241.

- ^ Genesis 13:1,3

- ^ Genesis 20:1

- ^ Genesis 21:22–34

- ^ Numbers 34:1–7; Joshua 15:1–3

- ^ Joshua 15:1–3

- ^ Joshua 19:1–9

- ^ Numbers 20:1–21:3

- ^ Deuteronomy 1–2

- ^ Detlef Jericke (2013). "Das "Bergland der Amoriter" in Deuteronomium 1" (PDF). Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 125 (1): 51.

- ^ Genesis 32:3; 33:12–16

- ^ Genesis 36:6–8

- ^ 1 Kings 9:26

- ^ Michael Evenari, Leslie Shanan, Naphtali Tadmor (1982). The Negev: The Challenge of a Desert. Harvard University Press. p. 18. ISBN 9780674606722. Retrieved 8 May 2018 – via Internet Archive.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ 1 Kings 11:14–25; 2 Kings 8:20–22; 2 Kings 16:6

- ^ Nadav Na'aman (2015). "Judah and Edom in the Book of Kings and in Historical Reality". In Rannfrid I. Thelle (ed.). New Perspectives on Old Testament Prophecy and History. Brill. pp. 197–211.

- ^ Numbers 20:14–16

- ^ Christian Frevel (2018). ""Esau, der Vater Edoms" (Gen 36,9.43): Ein Vergleich der Edom-Überlieferungen in Genesis und Numeri vor dem Hintergrund der historischen Entwicklung". In Mark G. Brett / Jakob Wöhrle (ed.). The Politics of the Ancestors. Exegetical and Historical Perspectives on Genesis 12–36. Mohr Siebeck. pp. 340–342. doi:10.15496/publikation-86105.

- ^ Horst Seebass (1993). Numeri. Neukirchener Verlag des Erziehungsvereins. pp. 409 f.

- ^ Robert D. Miller (2018). Yahweh: Origin of a Desert God. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 80 f.

The description of the first campaign of Seti I (1291 [B.C.]) on the north outer wall of the hypostyle hall of the Great Temple of Amun at Karnak provides an extended treatment of the Shasu. It places them in the 'hill country' of Khurru (Canaan) near Gaza (probably the western Negev, as there are no hills near Gaza), between the borders of Egypt at Tjaru and Pekanen (Canaan), where they were harassing the vassals of Egypt in Palestine (East of the Door, Scenes 1–11, esp. Scene 9, lines 104–108). [...] Some texts are even more precise. In Merneptah's Papyrus Anastasi 6.51–57 (COS 3.5), dated between 1226 and 1202, the 'Shasu of Edom' (probably Cisjordanian) are given permission to migrate west past the border fortresses at Tjeku (Sukkoth) into the Goshen region of Egypt. They are also called 'Shasu of Edom' in a letter from frontier official (638.14) during the reign of Siptah (fl. 1197–1191). In addition to the connection with Seir to be discussed below, Papyrus Harris 1 76.9–11 (COS 4.2; exploits of Rameses III written by Rameses IV; 1151 bc) speaks of the 'people of Seir among the tribes of Shasu.'

- ^ Juan Manuel Tebes (2008). Centro y periferia en el mundo antiguo. El Negev y sus interacciones con Egipto, Asiria, y el Levante en la Edad del Hierro (1200–586 a.C.) (PDF). Society of Biblical Literature / Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente. pp. 43–45.

- ^ Thomas E. Levy (2004). Richard Elliot Friedman / William H. C. Propp (ed.). Archaeology and the Shasu Nomads: Recent Excavations in the Jabal Hamrat Fidan, Jordan. Penn State University Press. pp. 70 f.

- ^ Juan Manuel Tebes (2008). Centro y periferia en el mundo antiguo. El Negev y sus interacciones con Egipto, Asiria, y el Levante en la Edad del Hierro (1200–586 a.C.) (PDF). Society of Biblical Literature / Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente. pp. 23–27.

- ^ Lily Singer-Avitz (2021). "Yotvata in the Southern Negev and Its Association with Copper Mining and Trade in the Early Iron Age". Near Eastern Archaeology. 84 (2): 101.

- ^ Uzi Avner (2022). "Yotvata: "A 'Fortress' on a Road Junction"". In Lily Singer-Avitz / Etan Ayalon (ed.). Yotvata. The Ze'ev Meshel Excavations (1974–1980). The Iron I "Fortress" and the Early Islamic Settlement. Eisenbrauns / Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology. pp. 11–19.

- ^ Erez Ben-Yosef (2012). "A New Chronological Framework for Iron Age Copper Production at Timna (Israel)". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 367: 31–71. doi:10.5615/bullamerschoorie.367.0031.

- ^ Ze'ev Herzog (1994). Israel Finkelstein / Nadav Na'aman (ed.). The Beer-Sheba Valley: From Nomadism to Monarchy. Israel Exploration Society. pp. 132 f.

- ^ Ze'ev Herzog / Lily Singer-Avitz (2002). "Redefining the Centre: The Emergence of the State in Judah". Tel Aviv. 31: 222.

- ^ Moshe Kochavi (1993). "Tel Malḥata". In Ephraim Stern (ed.). The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land. Volume 3. The Israel Exploration Society / Carta. p. 936.

- ^ Juan Manuel Tebes (2008). Centro y periferia en el mundo antiguo. El Negev y sus interacciones con Egipto, Asiria, y el Levante en la Edad del Hierro (1200–586 a.C.) (PDF). Society of Biblical Literature / Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente. p. 76.

- ^ Dan Gazit (2008). "Permanent and Temporary Settlements in the South of the Lower Besor Region: Two Case Studes". In Alexander Fantalkin / Assaf Yasur-Landau (ed.). Bene Israel. Studies in the Archaeology of Israel and the Levant During the Bronze and Iron Ages Offered in Honour of Israel Finkelstein. Brill. p. 77.

- ^ For examples, see "Central Negev Fortresses". Biblical Archaeology Society Library. Retrieved 2024-04-21.

- ^ Hendrik J. Bruins / Johannes van der Pflicht (2005). "Desert Settlement through the Iron Age: Radiocarbon dates from Sinai and the Negev Highlands". In Thomas E. Levy / Thomas Higham (ed.). The Bible and Radiocarbon Dating. Equinox.

- ^ Ayelet Gilboa (2009). "Notes on Iron IIA 14C Dates from Tell el-Qudeirat (Kadesh Barnea)". Tel Aviv. 36 (1): 88.

- ^ Elisabetta Boaretto (2010). "Radiocarbon Results from the Iron IIA Site of Atar Haroa in the Negev Highlands and Their Archaeological and Historical Implications". Radiocarbon. 52 (1): 1–12. Bibcode:2010Radcb..52....1B. doi:10.1017/S0033822200044982.

- ^ Hendrik J. Bruins (2022). "Masseboth Shrine at Horvat Haluqim: Amalekites in the Negev Highlands-Sinai Region? Evaluating the Evidence". Negev, Dead Sea and Arava Studies. 14 (2–4): 121–142.

- ^ Juan Manuel Tebes (2006). "Iron Age "Negevite" Pottery: A Reassessment". Antiguo Oriente. 4: 95–117.

- ^ Israel Finkelstein / Mario A. S. Martin (2013). "Iron IIA Pottery from the Negev Highlands: Petrographic Investigation and Historical Implications". Tel Aviv. 40: 6–45. doi:10.1179/033443513X13612671397305.

- ^ Mario A. S. Martin (2013). "Iron IIA slag-tempered pottery in the Negev Highlands, Israel". Journal of Archaeological Science. 40 (10): 3777–3792. Bibcode:2013JArSc..40.3777M. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2013.04.024.

- ^ Shirly Ben-Dor Evian (2017). "Follow the Negebite Ware Road". In Oded Lipschits (ed.). Rethinking Israel. Studies in the History and Archaeology of Ancient Israel in Honor of Israel Finkelstein. Eisenbrauns. p. 20.

- ^ Matthew D. Howland (2021). Long-Distance Trade and Social Complexity in Iron Age Faynan, Jordan (PDF) (Thesis). pp. 79–81.

- ^ a b Aren M. Maeir (2021). "Identity Creation and Resource Controlling Strategies: Thoughts on Edomite Ethnogenesis and Development". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 386: 211.

Further north, the so-called Iron IIA 'Israelite fortresses' of the Negev Highlands now show increasing evidence of being connected to the metal processing in the Arabah, most likely being used as waystations for the transportation of metal (and other trade items) towards the Meditreranean (or Egypt), probably controlled by the same group(s) that controlled the Arabah copper extraction [...]

- ^ Hendrik J. Bruins (2022). "Masseboth Shrine at Horvat Haluqim: Amalekites in the Negev Highlands-Sinai Region? Evaluating the Evidence". Negev, Dead Sea and Arava Studies. 14 (2–4): 138.

- ^ Rudolph Cohen (1985). "The Fortresses King Solomon Built to Protect His Southern Border. String of desert fortresses uncovered in Central Negev". Biblical Archaeological Review.

There can be no doubt that the Central Negev fortresses and settlements constitute the principal evidence of Israelite settlement in the area south of Beer-Sheva.

- ^ Gary N. Knoppers (1998). "The vanishing Solomon: the disappearance of the united monarchy from recent histories of ancient Israel". Journal of Biblical Literature. 116 (1): 30.

The reevaluation of material evidence has included the reinterpretation of Negev sites. [... T]he interpretation of the Negev sites as 'fortresses' has itself come under severe attack.

- ^ Israel Finkelstein (2013). "Geographical and Historical Realities behind the Earliest Layer in the David Story". Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament. 27 (2): 144.

Before 840 BCE, this was the location of the Tel Masos desert polity, which also encompassed the Iron IIA sites in the Negev Highlands, and which profited from participating in the mining of copper in the Arabah and the transportation of copper to the west.

- ^ Juan Manuel Tebes (2014). "Socio-Economic Fluctuations and Chiefdom Formation in Edom, the Negev and the Hejaz during the First Millennium BCE". Unearthing the Wilderness. Studies on the History and Archaeology of the Negev and Edom in the Iron Age. Peeters: 10–12.

- ^ Lester L. Grabbe (2017). Ancient Israel. What Do We Know and How Do We Know It? Revised Edition. Bloomsbury. pp. 81 f.

However, a number of scholars have now questioned this interpretation, arguing that they were desert settlements of local people who were possibly changing from a nomadic to a more settled lifestyle [...]. The main reason is that the location of the sites and their construction does not fit what would be expected of fortresses; furthermore, there was no renewal of them at a later time when Judah definitely controlled this area. [...] Copper from the area (see below) probably formed an important part of this trade, and when the copper trade declined, the 'Tel Masos polity' also declined.

- ^ Christian Frevel (2018). "Esau, der Vater Edoms" (Gen 36,9.43). Ein Vergleich der Edom-Überlieferungen in Genesis und Numeri vor dem Hintergrund der historischen Entwicklung" (PDF). The Politics of the Ancestors. Exegetical and Historical Perspectives on Genesis 12–36. Mohr Siebeck: 353.

- ^ Nadav Na'aman (2021). "Biblical Archaeology and the Emergence of the Kingdom of Edom" (PDF). Antiguo Oriente. 19: 19 f.

- ^ Piotr Bienkowski (2023). "The Emergence of Edom: Recent Debate". The Ancient Near East Today. 11 (3).

- ^ Piotr Bienkowski / Juan Manuel Tebes (2024). "Faynan, Nomads and the Western Negev in the Early Iron Age: A Critical Reappraisal". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 156 (3): 262–289. doi:10.1080/00310328.2023.2277628.

- ^ Erez Ben-Yosef (2020). "And Yet, a Nomadic Error: A Reply to Israel Finkelstein" (PDF). Antiguo Oriente. 18.

- ^ Benedikt Hensel (2021). "Edom in the Jacob Cycle (Gen 25–35). New Insights on Its Positive Relations with Israel, the Literary-Historical Development of Its Role, and Its Historical Background(s)" (PDF). The History of the Jacob Cycle (Genesis 25–35). Recent Research on the Compilation, the Redaction, and the Reception of the Biblical Narrative and Its Historical and Cultural Contexts. Mohr Siebeck: 69.

- ^ Erickson-Gini, Tali (2023-10-23). The Early Challenges of the United Kingdom of Israel Facing the Edomite Frontier 3000 Years Ago. Retrieved 2024-06-23. At 5:50 – 6:18.

See also 47:15 on the character of this lecture: "I know, a little bit is controversial. Some of it is coming from different ideas that were around for maybe up to 10 or 20 years ago. I think that if you talk to every researcher, you probably will get a little bit different idea – or maybe a lot different idea – than what I just told you about. But from my knowledge of these places, where they're placed along the roads, the topography, I don't think that there's any doubt that we're talking about something to do with some kind of fortifications in the Negev highlands in control of this region between Edom and the area of Judah, the united monarchy." - ^ Hendrik J. Bruins (2022). "Masseboth Shrine at Horvat Haluqim: Amalekites in the Negev Highlands-Sinai Region? Evaluating the Evidence". Negev, Dead Sea and Arava Studies. 14 (2–4).

- ^ Hendrik J. Bruins (2019). "Ancient runoff farming and soil aggradation in terraced wadi fields (Negev, Israel): Obliteration of sedimentary strata by ants, scorpions and humans". Quaternary International. 545: 87. Bibcode:2020QuInt.545...87B. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2019.11.027.

- ^ Yoav Avni (2022). "The Emergence of Terrace Farming in the Arid Zone of the Levant — Past Perspectives and Future Implications". Land. 11 (10).

- ^ a b Israel Finkelstein (2018). "The Archaeology and History of the Negev and Neighbouring Areas in the Third Millennium BCE: A New Paradigm". Tel Aviv. 45 (1): 65.

- ^ Cf. Jorge Silva Castillo (2008). "Nomadism Through the Ages". In Daniel C. Snell (ed.). A Companion to the Ancient Near East. Blackwell Publishing. p. 127.

In regions that receive 200 mm or eight inches of rain a year dry farming is possible; yet due to the recurring periods of drought, only an average annual rainfall of 300 mm or 12 inches permits truly reliable agricultural productivity [...]. The agropastoral populations knew how to exploit this transition zone between the desert and the zones that had enough rain or which could be artificially irrigated. Herds that pastured in the steppes or the highlands during the rainy season in the winter were led at the end of the spring to the banks of the rivers or to wadis, dry river beds. Sheep and goats fed on the pastures along river banks or on the stubble in the fertile fields, and with the manure they fertilized the fields.

- ^ G. Ore (2020). "Ancient cisterns in the Negev Highlands: Types and spatial correlation with Bronze and Iron Age sites". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 30. Bibcode:2020JArSR..30j2227O. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2020.102227.

- ^ Yehuda Kedar (1957). "Water and Soil from the Desert: Some Ancient Agricultural Achievements in the Central Negev". The Geographical Journal. 123 (2): 184. Bibcode:1957GeogJ.123..179K. doi:10.2307/1791318. JSTOR 1791318.

- ^ Michael Evenari (1975). "Antike Technik im Dienste der Landwirtschaft in ariden Gebieten". Der Tropenlandwirt. 76: 14, 16.

- ^ Gideon Avni (2014). The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach. Oxford University Press. p. 37.

- ^ Gideon Avni (2014). The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach. Oxford University Press. pp. 199 f.

- ^ Yoav Avni (2022). "The Emergence of Terrace Farming in the Arid Zone of the Levant — Past Perspectives and Future Implications". Land. 11 (10).

- ^ Yotam Tepper (2022). "Relict olive trees at runoff agriculture remains in Wadi Zetan, Negev Desert, Israel". Journal of Archaeological Science. 41. Bibcode:2022JArSR..41j3302T. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2021.103302.

- ^ Mordechai Haiman (1994). "The Iron Age II Sites of the Western Negev Highlands". Israel Exploration Journal. 44 (1/2): 49–53.

- ^ Steven A. Rosen (2017). Revolutions in the Desert. The Rise of Mobile Pastoralism in the Southern Levant. Chapter 10.5 (EPUB ed.). Routledge.

[...] Bruins (2007) has dated charcoal from sediments behind wadi channel terrace walls to the Iron Age [...], indicating the construction of the walls prior to the accumulation of the sediments. Thus, the terrace walls, agricultural dams for run-off irrigation, would constitute strong evidence for Iron Age farming. In addition, the presence of sickle segments in Iron Age sites in the region suggest reaping (e.g., Cohen and Cohen-Amin 2004:142).

- ^ Hendrik J. Bruins (2007). "Runoff Terraces in the Negev Highlands during the Iron Age: Nomads Settling Down or Farmers Living in the Desert?". In Benjamin A. Saidel / Eveline J. van der Steen (ed.). On the fringe of society. Archaeological and ethnoarchaeological perspectives on pastoral and agricultural societies. Archaeopress. p. 39.

- ^ Yoav Avni (2012). "Pre-farming environment and OSL chronology in the Negev Highlands, Israel". Journal of Arid Environments. 86: 15–18, 22. Bibcode:2012JArEn..86...12A. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2012.01.002.

- ^ Hendrik J. Bruins / Johannes Van Der Pflicht (2017). "Iron Age Agriculture — A Critical Rejoinder to "Settlement Oscillations in the Negev Highlands Revisited: the Impact of Microarchaeological Methods"". Radiocarbon. 59 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1017/RDC.2016.95.

- ^ Michael Evenari (1958). "The Ancient Desert Agricultre of the Negev: III. Early Beginnings". Israel Exploration Journal. 8 (4): 235.

- ^ Simon Gibson (1995). Landscape Archaeology and Ancient Agricultural Field Systems in Palestine (Thesis).

- ^ Oren Ackermann (2007). "Reading the field: Geoarchaeological codes in the Israeli landscape". Israel Journal of Earth Sciences. 56: 90.

- ^ Mordechai Haiman (2012). "Dating the agricultural terraces in the southern Levantine deserts – The spatial-contextual argument". Journal of Arid Environments. 86: 48 f. Bibcode:2012JArEn..86...43H. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2012.01.003.

- ^ Ruth Shahack-Gross / Israel Finkelstein (2008). "Subsistence practices in an arid environment: a geoarchaeological investigation in an Iron Age site, the Negev Highlands, Israel" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. 35 (4): 965–982. Bibcode:2008JArSc..35..965S. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2007.06.019.

- ^ Ruth Shahack-Gross / Israel Finkelstein (2017). "Iron Age Agriculture in the Negev Highlands? Methodological and Factual Comments on Bruins and van der Pflicht 2017a (Radiocarbon Vol. 59, Nr. 1)". Radiocarbon. 59 (4): 1227–1231. Bibcode:2017Radcb..59.1227S. doi:10.1017/RDC.2017.56.

- ^ a b Dafna Langgut / Israel Finkelstein (2023). "Environment, subsistence strategies and settlement seasonality in the Negev Highlands (Israel) during the Bronze and Iron Ages: The palynological evidence". PLOS ONE. 18 (5): e0285358. Bibcode:2023PLoSO..1885358L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0285358. PMC 10208521. PMID 37224129.

- ^ Erez Ben-Yosef (2017). "Beyond smelting: New insights on Iron Age (10th c. BCE) metalworkers community from excavations at a gatehouse and associated livestock pens in Timna, Israel". Journal of Archaeological Science. 11: 411–426. Bibcode:2017JArSR..11..411B. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2016.12.010.

- ^ Christian Frevel (2019). "State Formation in the Southern Levant: The Case of the Arameans and the Role of Hazael's Expansion". In Angelika Berlejung, Aharon Me'iyr (ed.). Research on Israel and Aram. Mohr-Siebeck.

- ^ Omer Sergi, Oded Lipschits (2011). "Judahite Stamped and Incised Jar Handles: A Tool for Studying the History of Late Monarchic Judah". Tel Aviv. 38 (1): 10.

- ^ Especially Arad ostraca 24 ("Now I send (this message) in order to solemnly admonish you; today the men (must be) with Elisha, lest Edom should go there [to ra`mat negeb; location uncertain].") and 40 ("... the evil tha[t] Edo[m did(?)]"). Quoted after F. W. Dobbs-Allsopp (2005). Hebrew Inscriptions. Texts from the Biblical Period of the Monarchy with Concordance. Yale University Press. pp. 49, 70.

- ^ Laura M. Zucconi (2007). "From the Wilderness of Zin alongside Edom: Edomite Territory in the Eastern Negev during the Eighth-Sixth Centuries B.C.E.". In Sarah Malena, David Miano (ed.). Milk and Honey. Essays on Ancient Israel and the Bible in Appreciation of the Judaic Studies Program at the University of California. Pennsylvania State University Press.

- ^ Israel Eph´al (2003). "ראשיתה של אידומיאה". קדמוניות (in Hebrew). 126.

- ^ Itzhaq Beit-Arieh (2009). "Judah versus Edom in the Eastern Negev" (PDF). Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan. 10.

- ^ Eli Cohen-Sasson (2021). "Gorer Tower and the Biblical Edom Road". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 153 (2).

- ^ Bert Dicou (1994). Edom, Israel's Brother and Antagonist. The Role of Edom in Biblical Prophecy and Story. JSOT Press. p. 187.

- ^ Elie Assis (2006). "Why Edom? On the hostility towards Jacob's brother in prophetic Sources". Vetus Testamentum. 56 (1): 4.

- ^ Bob Becking (2016). "The betrayal of Edom: Remarks on a claimed tradition". HTS Teologiese Studies. 72 (4): 3.

- ^ Juan Manuel Tebes (2019). "Memories of humiliation, cultures of resentment towards Edom and the formation of ancient Jewish national identity" (PDF). Nations and Nationalism. 25 (1): 131 f.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica xix 94 f, 98.

- ^ Josephus, Contra Apionem II.9 116.

- ^ David Luria (2021). "Copper technology in the Arabah during the Iron Age and the role of the indigenous population in the industry". PLOS ONE. 16 (12): e0260518. Bibcode:2021PLoSO..1660518L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0260518. PMC 8687555. PMID 34928961.

- ^ David Mattingly (2007). "The Making of Early States: The Iron Age and Nabatean Periods". In Graeme Barker (ed.). Archaeology and Desertification. The Wadi Faynan landscape survey. Council for British Research in the Levant. p. 285.

- ^ Erez Ben-Yosef (2010). Technology and Social Process: Oscillations in Iron Age Copper Production and Power in Southern Jordan (Thesis). pp. 959 f.

- ^ Mark Cavanagh (2022). "Fuel exploitation and environmental degradation at the Iron Age copper industry of the Timna Valley, southern Israel". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 15434. Bibcode:2022NatSR..1215434C. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-18940-z. PMC 9492654. PMID 36130974.

- ^ Erez Ben-Yosef (2012). "A New Chronological Framework for Iron Age Copper Production at Timna (Israel)". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 367: 65.

- ^ Lidar Sapir-Hen, Erez Ben-Yosef (2013). "The Introduction of Domestic Camels to the Southern Levant: Evidence from the Aravah Valley". Tel Aviv. 40 (2): 277−285. doi:10.1179/033443513X13753505864089.

- ^ Juan Manuel Tebes (2014). "Socio-Economic Fluctuations and Chiefdom Formation in Edom, the Negev and the Hejaz during the First Millennium BCE". In Juan Manuel Tebes (ed.). Unearthing the Wilderness: Studies on the History and Archaeology of the Negev and Edom in the Iron Age. Peeters. pp. 14−19.

- ^ Christian Frevel (2019). "State Formation in the Southern Levant – The Case of the Aramaeans and the Role of Hazael's Expansion". In Angelika Berlejung, Aren M. Maeir (ed.). Research on Israel and Aram: Autonomy, Interdependence and Related Issues. Proceedings of the First Annual RIAB Center Conference, Leipzig, June 2016 (RIAB I). Mohr Siebeck. pp. 364 f.

- ^ Jakob Wöhrle (2019). "Edom / Edomites". WiBiLex.

- ^ Israel Finkelstein (2020). "The Arabah Copper Polity and the Rise of Iron Age Edom: A Bias in Biblical Archaeology?". Antiguo Oriente. 18: 22 f.

- ^ Nadav Na'aman (2021). "Biblical Archaeology and the Emergence of the Kingdom of Edom" (PDF). Antiguo Oriente. 19: 22.

- ^ Erez Ben-Yosef (2023). "A False Contrast? On the Possibility of an Early Iron Age Nomadic Monarchy in the Arabah (Early Edom) and Its Implications for the Study of Ancient Israel". In Ido Koch (ed.). From Nomadism to Monarchy? Revisiting the Early Iron Age Southern Levant. Eisenbrauns. pp. 241−243.

- ^ Itzhaq Beit-Arieh. "New Light on the Edomites". Biblical Archaeology Review. March/April 1988.

- ^ Juan Manuel Tebes (2008). "Centro y periferia en el mundo antiguo. El Negev y sus interacciones con Egipto, Asiria, y el Levante en la Edad del Hierro (1200–586 a.C.)" (PDF). Society of Biblical Literature / Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente: 87 f.

- ^ Itzhaq Beit-Arieh (2009). "Judah Versus Edom in the Eastern Negev". Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan. 10: 597–602.

- ^ Yifat Thareani (2010). "The Spirit of Clay: "Edomite Pottery" and Social Awareness in the Late Iron Age". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 359: 51 f.

- ^ Thomas L. Thompson (2014). "Changing perspectives on the history of Palestine". In Idem (ed.). Biblical Narrative and Palestine′s History. Changing Perspectives 2. Routledge. p. 332.

- ^ Robert Wenning (2007). "The Nabataeans in History (Before AD 106)". In Konstantinos D. Politis (ed.). The Nabataeans in History. The World of the Nabataeans. Volume 2 of the International Conference "The World of the Herods and the Nabataeans" held at the British Museum, 17 – 19 April 2001. Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 26 f. doi:10.11588/propylaeumdok.00000628.

- ^ a b Christian Augé (2013). "The Nabataean Age (4th century BC – 1st century AD)". In Myriam Ababsa (ed.). Atlas of Jordan. Contemporain publications. Presses de l´Ifpo. pp. 142–150. ISBN 978-2-35159-438-4.

- ^ David F. Graf, Arnulf Hausleiter (2021). "The Arabian World". In Bruno Jacobs, Robert Rollinger (ed.). A Companion to the Achaemenid Persian Empire. Volume I. Wiley Blackwell. pp. 533 f.

- ^ Avraham Negev (1967). "New Dated Nabatean Graffiti from the Sinai". Israel Exploration Journal. 17 (4): 250–255.

- ^ Avraham Negev (1982). "Nabatean Inscriptions in Southern Sinai". Biblical Archaeologist. 45 (1): 21–25. doi:10.2307/3209845. JSTOR 3209845.

- ^ Mustafa Nour el-Din (2023). "New Nabataean and Thamudic Inscriptions from Al-Manhal Site, Southwest Sinai". Abgadiyat. 17: 25–41. doi:10.1163/22138609-01701005.

- ^ Mahmoud S. Ghanem, Eslam Sami Abd El-Baset (2023). "Unpublished Nabataean Inscriptions from Southern Sinai". Abgadiyat. 17: 43–58. doi:10.1163/22138609-01701006.

- ^ Tali Erickson-Gini, Yigal Israel (2013). "Excavating the Nabataean Incense Road". Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies. 1 (1): 24–53. doi:10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.1.1.0024.

- ^ Ababsa, Myriam (11 June 2014). Atlas of Jordan. Presses de l’Ifpo. ISBN 978-2-35159-438-4. Retrieved 2024-04-28.

- ^ E. Ashtor (1976). A Social and Economic History of the Near East in the Middle Ages. University of California Press. pp. 55, 58.

- ^ Tali Erickson-Gini (2012). "Nabataean agriculture: Myth and reality". Journal of Arid Environments. 86: 50. Bibcode:2012JArEn..86...50E. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2012.02.018.

- ^ Gideon Avni (2013). "Byzantine–early Islamic agricultural systems in the Negev Highlands: Stages of development as interpreted through OSL dating". Journal of Field Archaeology. 38 (4): 340.

- ^ P. M. Michèle Daviau, Christopher M. Foley (2007). "Nabataean Water Management Systems in the Wādī ath-Thamad". Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan. 09: 360 f.

- ^ Tali Erickson-Gini, Yigal Israel (2013). "Excavating the Nabataean Incense Road". Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies. 1 (1): 41.

- ^ Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews.

JosAnt 13.257 f.

- ^ Michał Marciak (2020). "Persecuted or Persecutors? The Maccabean–Idumean Conflict in the Light of the First and Second Books of the Maccabees". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 136 (1).

- ^ E.g. Goodman, Martin (1994). Mission and Conversion. Proselytizing in the Religious History of the Roman Empire. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-0-19-814941-5.

- ^ E.g. Chapman, Honora H. (2006). "Paul, Josephus, and the Judean Nationalistic and Imperialistic Policy of Forced Circumcision". 'Ilu. Revista de Ciencias de las Religiones. 11: 138–143.

- ^ E.g. van Maaren, John (2022). The Boundaries of Jewishness in the Southern Levant, 200 BCE–132 CE. Power, Strategies, and Ethnic Configurations. Berlin / Boston: de Gruyter. pp. 114–118. ISBN 978-3-11-078745-0.

- ^ Achim Lichtenberger (2007). Linda-Marie Günther (ed.). "Juden, Idumäer und "Heiden". Die herodianischen Bauten in Hebron und Mamre". Herodes und Rom. Franz Steiner Verlag: 78, fig. 14.

- ^ Faust, Avraham; Ehrlich, Adi (2011). The Excavations of Khirbet er-Rasm, Israel. The changing faces of the countryside. Oxford: BAR Publishing. pp. 251–252.

- ^ Cf., however, Finkielsztejn, Gerald (1998). "More Evidence on John Hyrcanus I's Conquests: Lead Weights and Rhodian Amphora Stamps". Bulletin of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society. 16: 47–48.; Atkinson, Kenneth (2016). A History of the Hasmonean State. Josephus and Beyond. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-567-66903-2.: Gradually abandoned, with no signs of destruction. Both nevertheless assume, due to the mikvaot in Maresha, that a remaining population converted to Judaism; however, on the Maresha mikvaot, see below and cf. alternatively Stern, Ian (2022). "The Evolution of an Edomite Idumean Identity. Hellenistic Period Maresha as a Case Study". In Hensel, Benedikt; Ben Zvi, Ehud; Edelman, Diana V. (eds.). About Edom and Idumea in the Persian Period. Recent Research and Approaches from Archaeology, Hebrew Bible Studies and Ancient Near Eastern Studies. Sheffield / Bristol: Equinox. p. 18 FN 53.: "Maresha was abandoned ca. 112/111 BCE, meaning that the bathing installations date to before the Hasmonean conquest."

- ^ Cf., however, Ussishkin, David (2014). Biblical Lachish. A Tale of Construction, Destruction, Excavation and Restoration. Vol. 151. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society / Biblical Archaeology Society. p. 392.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help): Gradually abandoned over the course of the 2nd century. - ^ Itzhaq Beit-Arieh, Liora Freud (2015). Tel Malḥata. A Central City in the Biblical Negev. Volume I. Eisenbrauns. pp. 17 f.

- ^ Atkinson, Kenneth (2016). A History of the Hasmonean State. Josephus and Beyond. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-0-567-66903-2.

- ^ Débora Sandhaus (2021). "Settlements and Borders in the Shephelah from the Fourth to the First Centuries BCE". In Andrea M. Berlin, Paul J. Kosmin (ed.). The Middle Maccabees. Archaeology, History, and the Rise of the Hasmonean Kingdom. Atlanta: SBL Press. p. 89.

- ^ Ian Stern (2012). "Ethnic Identities and Circumcised Phalli at Hellenistic Maresha". Strata. 30: 63–74.

- ^ Yigal Levin (2020). "The Religion of Idumaea and Its Relationship to Early Judaism". Religions. 11 (10): 17 of the PDF.

- ^ Stern, Ian (2022). "The Evolution of an Edomite Idumean Identity. Hellenistic Period Maresha as a Case Study". In Hensel, Benedikt; Ben Zvi, Ehud; Edelman, Diana V. (eds.). About Edom and Idumea in the Persian Period. Recent Research and Approaches from Archaeology, Hebrew Bible Studies and Ancient Near Eastern Studies. Sheffield / Bristol: Equinox. pp. 17–18. Paginazion according to linked Open Access version.

- ^ Magen, Y. (2003). "Mamre. A Cultic Site from the Reign of Herod". In Bottini, G. C.; Disegni, L.; Chrupcala, L. D. (eds.). One Land – Many Cultures. Archaeological Studies in Honour of St. Loffreda OFM. Jerusalem: Franciscan Printing Press. pp. 245–257.

- ^ Vlastimil Drbal (2017). "Pilgrimage and multi-religious worship. Palestinian Mamre in Late Antiquity". In Troels M. Kristensen, Wiebke Friese (ed.). Excavating Pilgrimage. Archaeological Approaches to Sacred Travel and Movement in the Ancient World. Routledge. pp. 250 f., 255–257.

- ^ Michał Marciak (2017). "Idumea and the Idumeans in Josephus' Story of Hellenistic-Early Roman Palestine (Ant XII–XX)" (PDF). Aevum. 91 (1): 185 f.

- ^ Cornell, Collin (2020). "The Costobar Affair: Comparing Idumaism and early Judaism". Journal of the Jesus Movement in Its Jewish Setting. 7: 97–98.

- ^ Katharina Heyden (2020). "Construction, Performance, and Interpretation of a Shared Holy Place. The Case of Late Antique Mamre (Rāmat al-Khalīl)". Entangled Religions. 11 (1).

- ^ Cohen, Shaye J. D. (1999). The Beginnings of Jewishness. Boundaries, Varieties, Uncertainties. Berkeley / Los Angeles / London: University of California Press. pp. 116–117. ISBN 978-0-520-21141-4.

- ^ Pasto, James (2002). "Origin, Impact, and Expansion of the Hasmoneans in Light of Comparative Ethnographic Studies (and Outside of its Nineteenth Century Context)". In Davies, Philip R.; Halligan, John M. (eds.). Second Temple Studies III. Studies in Politics, Class and Material Culture. London / New York: Sheffield Academic Press. pp. 197–198.

- ^ Eckhardt, Benedikt (2012). ""An Idumean, That Is, a Half-Jew". Hasmoneans and Herodians between Ancestry and Merit". Jewish Identity and Politics between the Maccabees and Bar Kokhba. Leiden: Brill. pp. 100–102.

- ^ Kasher, Aryeh (1988). Jews, Idumaeans, and Ancient Arabs. Relations of the Jews in Eretz-Israel with the Nations of the Frontier and the Desert During the Hellenistic and Roman Era (332 BCE-70 CE). Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. pp. 46–48. ISBN 978-3-16-145240-6.

- ^ Weitzman, Steven (1999). "Forced Circumcision and the Shifting Role of Gentiles in Hasmonean Ideology". The Harvard Theological Review. 92 (1): 37–59. doi:10.1017/S0017816000017843. ISSN 0017-8160. JSTOR 1510155. S2CID 162887617.

- ^ Thomas L. Thompson (2018). "The Problem of Israel in the History of the South Levant". In Lester L. Grabbe (ed.). "Even God Cannot Change the Past". Reflections on Seventeen Years of the European Seminar in Historical Methodology. T&T Clark. p. 84.

- ^ Uzi Avner (1984). "Ancient Cult Sites in the Negev and Sinai Deserts". Tel Aviv. 11: 117 f.

- ^ Noé D. Michael (2022). Settlement Patterns in the Northern Negev from the Hellenistic through the Early Islamic Periods. Propylaeum. p. 109. doi:10.11588/propylaeum.1121. ISBN 978-3-96929-195-5.

- ^ Noé D. Michael (2022). Settlement Patterns in the Northern Negev from the Hellenistic through the Early Islamic Periods. Propylaeum. pp. 89, 122. doi:10.11588/propylaeum.1121. ISBN 978-3-96929-195-5.

- ^ Magen Broshi (1979). "The Population of Western Palestine in the Roman-Byzantine Period" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 236: 5.

- ^ Israel Finkelstein (2018). "The Archaeology and History of the Negev and Neighbouring Areas in the Third Millennium BCE: A New Paradigm". Tel Aviv. 45 (1): 65.

- ^ "Digital Corpus of Early Christian Churches and Monasteries in the Holy Land". Retrieved 2024-04-28.

- ^ Gideon Avni (2014). The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach. Oxford University Press. pp. 261–263.

- ^ Jodi Magness (2003). The Archaeology of the Early Islamic Settlement in Palestine. Eisenbrauns. pp. 131, 133.

- ^ a b Gideon Avni (2014). The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach. Oxford University Press. p. 286.

- ^ Moshe Gil (1992). A History of Palestine. 634–1099. Cambridge University Press. pp. 18 f.

- ^ Itamar Taxel (2018). "Early Islamic Palestine: Toward a More Fine-Tuned Recognition of Settlement Patterns and Land Uses in Town and Country". Journal of Islamic Archaeology. 5 (2): 156.

- ^ Steven A. Rosen (2000). "The decline of desert agriculture: a view from the classical period Negev". In Graeme Barker, David Gilbertson (ed.). The Archaeology of Drylands. Living at the margin. Routledge. pp. 52 f.

- ^ Gideon Avni (2008). "The Byzantine Islamic Transition in the Negev". Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam. 35: 5.

- ^ Gideon Avni (1994). "Early Mosques in the Negev Highlands: New Archaeological Evidence on Islamic Penetration of Southern Palestine". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 294: fig. 5.

- ^ Gideon Avni (2014). The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach. Oxford University Press. pp. 266, 271, 284 f.

- ^ a b Milka Levy-Rubin (2000). "New Evidence Relating to the Process of Islamization in the Early Muslim Period – The Case of Samaria". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 43 (3): 262.

- ^ Philip K. Hitti (1972). "The Impact of the Crusades on Eastern Christianity". In Sami A. Hanna (ed.). Medieval and Middle Eastern Studies in Honor of Aziz Suryal Atiya. E. J. Brill. p. 212.

- ^ Hugh Kennedy (1985). "From Polis to Madina: Urban Change in Late Antique and Early Islamic Syria". Past and Present (106): 3–27.

- ^ Alan G. Walmsley (1996). "Byzantine Palestine and Arabia: Urban Prosperity in Late Antiquity". In Neil Christie, S. T. Loseby (ed.). Towns in Transition. Urban evolution in late antiquity and the early Middle Ages. Scolar Press. pp. 138–143.

- ^ Gideon Avni (2014). The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach. Oxford University Press. pp. 15 f., 98, 102.

- ^ Scott Bucking, Tali Erickson-Gini (2020). "The Avdat in Late Antiquity Project: Report on the 2012/2016 Excavation of a Cave and Stone-Built Compound along the Southern slope". Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies. 8 (1): 47 f.

- ^ Michael Ehrlich (2022). The Islamization of the Holy Land, 634–1800. Arc Humanities Press. p. 45.

- ^ Yizhar Hirschfeld (2006). "The Crisis of the Sixth Century: Climatic Change, Natural Disasters and the Plague". Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry. 6 (1): 19–32. Bibcode:2006MAA.....6...19H.

- ^ Dov Nahlieli (2007). "Settlement Patterns in the Late Byzantine and Early Islamic Periods in the Negev, Israel". In Benjamin A. Saidel, Eveline J. van der Steen (ed.). On the Fringe of Society: Archaeological and Ethnoarchaeological Perspectives on Pastoral and Agricultural Societies. BAR Publishing. pp. 80 f.

- ^ a b Ariel David (29 July 2020). "How Volcanoes and Plague Killed the Byzantine Wine Industry in Israel". Haaretz. Retrieved 2020-08-04.

- ^ Jon Seligman (2023). "Yavne and the industrial production of Gaza and Ashqelon wines". Levant. 55 (3).

- ^ Daniel Fuks (2020). "The rise and fall of viticulture in the Late Antique Negev Highlands reconstructed from archaeobotanical and ceramic data". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117 (33): 19780–19791. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11719780F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1922200117. PMC 7443973. PMID 32719145.

- ^ Daniel Fuks (2021). "The Debate on Negev Viticulture and Gaza Wine in Late Antiquity". Tel Aviv. 48 (2): 162 f. doi:10.1080/03344355.2021.1968626.

- ^ Jon Seligman (2023). "Yavne and the industrial production of Gaza and Ashqelon wines". Levant. 55 (3): 20.

- ^ Michael Decker (2009). Tilling the Hateful Earth. Agricultural Production and Trade in the Late Antique East. Oxford University Press. pp. 138: "It is also clear that the production of fine wines in Palestine did not immediately end with the Islamic conquests. In the Umayyad period (AD 661–750), Arab writers praised the wines of Capitolias (Beit Ras) and Gadara (Umm Qays), both in the region of the former province of Paleaestina II.".

- ^ Gideon Avni (2020). "Terraced Fields, Irrigation Systems and Agricultural Production in Early Islamic Palestine and Jordan: Continuity and Innovation". Journal of Islamic Archaeology. 7 (2): 118.

- ^ a b Andrew Petersen (2005). The Towns of Palestine under Muslim Rule AD 600–1600. Archaeopress. p. 46.

- ^ Jodi Magness (2003). The Archaeology of the Early Islamic Settlement in Palestine. Eisenbrauns. pp. 1 f, 131.

- ^ Itamar Taxel (2013). "Rural Settlement Processes in Central Palestine, ca. 640–800 C.E.: The Ramla-Yavneh Region as a Case Study". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 369: 159.

- ^ Gideon Avni (2014). The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach. Oxford University Press. p. 263.

- ^ Noé D. Michael (2022). Settlement Patterns in the Northern Negev from the Hellenistic through the Early Islamic Periods. Propylaeum. p. 128. doi:10.11588/propylaeum.1121. ISBN 978-3-96929-195-5.

- ^ Steven A. Rosen (2000). "The decline of desert agriculture: a view from the classical period Negev". In Graeme Barker, David Gilbertson (ed.). The Archaeology of Drylands. Living at the margin. Routledge. pp. 53 f.

- ^ Gideon Avni (2014). The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach. Oxford University Press. p. 282.

- ^ Mordechai Haiman (1995). "Agriculture and Nomad-State Relations in the Negev Desert in the Byzantine and Early Islamic Periods". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 297: 41 f.

- ^ Daniel Fuks (2021). "The Debate on Negev Viticulture and Gaza Wine in Late Antiquity". Tel Aviv. 48 (2): 157. doi:10.1080/03344355.2021.1968626.

- ^ Yoav Avni (2022). "The Emergence of Terrace Farming in the Arid Zone of the Levant - Past Perspectives and Future Implications". Land. 11 (10): 11 of the PDF.

- ^ Guy Bar-Oz (2019). "Ancient trash mounds unravel urban collapse a century before the end of Byzantine hegemony in the southern Levant". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116 (17): 8239–8248. Bibcode:2019PNAS..116.8239B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1900233116. PMC 6486770. PMID 30910983.

- ^ Gideon Avni (2014). The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach. Oxford University Press. p. 264.

- ^ Scott Bucking, Tali Erickson-Gini (2020). "The Avdat in Late Antiquity Project: Report on the 2012/2016 Excavation of a Cave and Stone-Built Compound along the Southern slope". Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies. 8 (1): 36, 51 f.

- ^ Scott Bucking, Tali Erickson-Gini (2020). "The Avdat in Late Antiquity Project: Report on the 2012/2016 Excavation of a Cave and Stone-Built Compound along the Southern slope". Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies. 8 (1): 36.

- ^ Uzi Avner, Jodi Magness (1998). "Early Islamic Settlement in the Southern Negev". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 310.

- ^ Jodi Magness (2003). The Archaeology of the Early Islamic Settlement in Palestine. Eisenbrauns. p. 194.

- ^ Gideon Avni (2014). The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach. Oxford University Press. pp. 257–259, 263–267, 282 f., 287.

- ^ Andrew Petersen (2005). The Towns of Palestine under Muslim Rule AD 600–1600. Archaeopress. p. 47.

- ^ Yotam Tepper (2020). "Sustainable farming in the Roman-Byzantine period: Dating an advanced agriculture system near the site of Shivta, Negev Desert, Israel". Journal of Arid Environments. 177: fig. 20. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2020.104134.

- ^ Rasmussen, Carl (4 July 2020). "Negev Agriculture: Tuleilat al-Anab". Holy Land Photos. Retrieved 4 Dec 2023.

- ^ Lavee, Hanoch (1997). "Evidence of high efficiency water-harvesting by ancient farmers in the Negev Desert, Israel". Journal of Arid Environments. 35 (2): 341–348. Bibcode:1997JArEn..35..341L. doi:10.1006/jare.1996.0170.

- ^ Boyko, H. (1966). "Ancient and Present Climatic Features in South-West Asia and the Problem of the Antique Mounds of Grapes ("Teleilat el-´Anab") in the Negev". International Journal of Biometerology. 10 (3): 228–229. Bibcode:1966IJBm...10..223B. doi:10.1007/BF01426222.

- ^ Lightfoot, Dale R. (1996). "The Nature, History, and Distribution of Lithic Mulch Agriculture: An Ancient Technique of Dryland Agriculture". The Agricultural History Review. 44 (2): 211–212. JSTOR 40275100.

- ^ Bruins, Hendrik J. (2024). "The Anthropogenic "Runoff" Landscape of the Central Negev Desert". In Frumkin, Amos; Shtober-Zisu, Nurit (eds.). Landscapes and Landforms of Israel. Springer. p. 348.

- ^ Tepper, Yotam (2017). "Signs of soil fertigation in the desert: A pigeon tower structure near Byzantine Shivta, Israel". Journal of Arid Environments. 145: 81–89. Bibcode:2017JArEn.145...81T. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2017.05.011.

- ^ Tepper, Yotam (2020). "Sustainable farming in the Roman–Byzantine period: Dating an advanced agriculture system near the site of Shivta, Negev Desert, Israel". Journal of Arid Environments. 177. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2020.104134.

- ^ Fuks, Daniel (2021). "The Debate on Negev Viticulture and Gaza Wine in Late Antiquity". Tel Aviv. 48 (2): 161. doi:10.1080/03344355.2021.1968626.

- ^ Rubin, Rehav (1988). "Water conservation methods in Israel's Negev desert in late antiquity". Journal of Historical Geography. 14 (3): 241–242. doi:10.1016/S0305-7488(88)80220-2.

- ^ Lightfoot, Dale R. (1997). "Qanats in the Levant: Hydraulic Technology at the Periphery of Early Empires". Technology and Culture. 38 (2): 432–435. doi:10.2307/3107129. JSTOR 3107129.

- ^ Avner, Uzi; Magness, Jodi (1998). "Early Islamic Settlement in the Southern Negev". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 310 (310): 46–49. doi:10.2307/1357577. JSTOR 1357577.

- ^ Avner, Uzi (2015). "Desert Farming in the Southern ´Araba Valley, Israel, 2nd Century BCE to 11th Century CE". In Retamero, Fèlix (ed.). Agricultural and Pastoral Landscapes in Pre-industrial Society. Choices, Stability and Change. Oxbow Books. p. 33.

- ^ Stavi, Ilan (2021). "Ancient to recent-past runoff harvesting agriculture in the hyper-arid Arava Valley: OSL dating and insights". The Holocene. 31 (6): 1051. Bibcode:2021Holoc..31.1047S. doi:10.1177/0959683621994641.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch