Anne Sutton

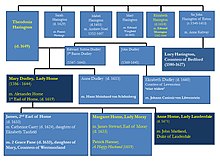

Anne Sutton (1589–1615) was an English lady-in-waiting who was a companion of Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia. She was the daughter of Edward Sutton, 5th Baron Dudley and Theodosia Harington. Sutton was known as "Mrs Anne Dudley" or "Mistress Dudley" although "Sutton" was the family surname. Elizabeth of Bohemia called her "Nan Duddlie".[1]

Early life

[edit]Her father abandoned Theodosia, Lady Harington for his mistress, Elizabeth Tomlinson. According to a bill produced in the Star Chamber by his political rival in Staffordshire, Gilbert Lyttelton,[2] in 1592 he had "left that virtuous lady his wife in London without sustenance, and took to his home a lewd and infamous woman, a base collier's daughter".[3]

In 1597, Anne and her brother, Ferdinando Sutton, were lodged in Clerkenwell with Euseby Paget, rector of St Anne and St Agnes, and Mrs Percy, as wards of their aunt and uncle Elizabeth and Edward Montagu of Boughton.[4] Lord Dudley did not fully honour the details of the settlement and payments proposed by the Privy Council.[5]

Career in a royal household

[edit]Anne Dudley became a member of the household of Princess Elizabeth at Coombe Abbey with other young women including her cousin Elizabeth Dudley, with Anne Livingstone, Frances Bourchier, and Philadelphia Carey. Her older sister, Mary, married Alexander Home, 1st Earl of Home in 1605. After Elizabeth married Frederick V of the Palatinate in 1613 she went with her to Heidelberg.[6]

In 1612, an emblem published in Henry Peacham's Minerva Brittana alluded to her steadfast qualities as alike to Diana the huntress, with a picture of Diana and Actaeon, a verse, and an anagram on her name in Italian "e l'nuda Diana".[7] The intended allusion was possibly to her labour and skills as a household administrator. The concept was derived from an emblem devised by Laurens van Haecht Goidtsenhoven.[8]

Anne with seven other ladies put their names in a hat to award kisses to winners at a tournament for Prince Henry in April 1612. The others included the Countess of Essex, Lady Cranbourne, Lady Windsor, and Lady Stanhope.[9]

As a New Year gift in January 1613, Anne Dudley received from Frederick V of the Palatinate a chain of pearls and a diamond worth 1,000 marks, (£666-13s-8d).[10] John Chamberlain noted this gift as a single item, a chain of pearls and diamonds worth £500.[11]

She travelled to Heidelberg after the wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Frederick V of the Palatinate. Princess Elizabeth's female attendants on her arrival at Vlissingen on 29 April 1613 were listed as the Countess of Arundel, Lady Harington, Lady Cecil, Mistress Anne Dudley, Mistress Elizabeth Dudley, Mistress Apsley, and Mistress (Mary) Mayerne.[12]

At the christening of Henry Frederick, Hereditary Prince of the Palatinate in March 1614 she received jewels worth £200.[13]

Anne married Hans Meinhard von Schönberg, the Palatine Ambassador to England, and resident diplomat at Heidelberg, in London on 22 March 1615.[14] The wedding was celebrated with a masque of ballet planned by Elizabeth and Salomon de Caus, whose wife seems have been involved in supplying fabrics for costumes. Inigo Jones had designed a banqueting hall for the castle.[15]

Their romance was well-known. It was said in London in December 1613 that Schönberg came to England in part to entreat King James and Anne of Denmark not to recall Dudley from Heidelberg.[16] They were betrothed before 5 April 1614,[17] and this was publicly known in June 1614.[18] In July it was known abroad they were in love.[19]

She quarrelled with Elizabeth Apsley, a maid of honour and a distant cousin of Lucy Hutchinson.[20]

James VI and I wrote to ask if a maid of honour could be a married woman in German custom, and what royal jewels were in her care. Elizabeth, the Electress, replied that Dudley only kept some silver plate, and also that her husband, Frederick V and his council had favoured the marriage.[21]

Her son was Frederick Schomberg, 1st Duke of Schomberg.[22] Anne died of a fever after giving birth to Frederick.[23]

In her 1644 will her sister, Mary (Dudley) Sutton, Countess of Home, left her nephew, Frederick Schomberg, a purse of gold coins.[24]

References

[edit]- ^ Nadine Akkerman, Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Hearts (Oxford, 2021), p. 113.

- ^ S. M. Thorpe, 'LYTTELTON, Gilbert (c.1540-99)', The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1558-1603, ed. P.W. Hasler, 1981

- ^ Henry Sydney Grazebrook, 'An Account of the Barons of Dudley', Collections for a History of Staffordshire, vol. 9 (1880), pp. 111-112.

- ^ Acts of the Privy Council, vol. 27, pp. 325-328: Charles Carlton, State, Sovereigns & Society in Early Modern England (New York, 1998), p. 212: 'DUDLEY, alias SUTTON, Edward (1567-1643), of Dudley Castle, Staffs.' The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1558-1603, ed. P.W. Hasler, 1981.

- ^ Lamar M. Hill, 'The Privy Council and Private Morality', Charles Carlton, State Sovereigns & Society in Early Modern England (Stroud: Sutton, 1998), 212.

- ^ Mary Anne Everett Green, Elizabeth of Bohemia (London, 1909), pp. 9, 18, 44, 48, 96.

- ^ Henry Peacham, Minerva Britanna (London, 1612), p. 175.

- ^ Judith Dundas, 'Imitation and Originality in Peacham's Emblems' in Bart Westerweel, Symbola et Emblemata, vol. 8, 'Anglo-Dutch Relations in the Field of the Emblem' (Leiden, 1997), pp. 114-118.

- ^ A. B. Hinds, HMC Downshire, vol. 3 (London, 1938) p. 276 (The index suggests Theodosia Dudley rather than her daughter).

- ^ A. B. Hinds, HMC Report on the Manuscripts of the Marquess of Downshire, vol. 4 (London, 1940), p. 2

- ^ Norman Egbert McClure, Letters of John Chamberlain, vol. 1 (1939), p. 413

- ^ Edmund Howes, Annales, or Generall Chronicle of England (London, 1615), p. 919.

- ^ A. B. Hinds, HMC Downshire, vol. 4 (London, 1940), p.337.

- ^ Nichola Hayton, 'The Other Wedding of Thames and Rhine: Lady Anne Sutton Dudley and Colonel Hans Meinhard von Schönberg', Nichola M. V. Hayton, Hanns Hubach, Marco Neumaier, Churfürstlicher Hochzeitlicher Heimführungs Triumph (Ubstadt-Weiher: Verlag Regionalkultur, 2020), pp. 169-190.

- ^ Nadine Akkerman, Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Hearts (Oxford, 2021), pp. 111-112.

- ^ The Court and Times of James the First, vol. 1 (London, 1848), p. 283

- ^ Nadine Akkerman, The Correspondence of Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia, vol. 1 (Oxford, 2015), pp. 151-152.

- ^ Folkestone Williams & Thomas Birch, The Court and Times of James the First, vol. 1 (London, 1848), p. 325.

- ^ A. B. Hinds, HMC Downshire, vol. 4 (London, 1940), p. 445 & fn.

- ^ Mary Anne Everett Green, Elizabeth of Bohemia (London, 1909), pp. 418-419.

- ^ Mary Anne Everett Green, Elizabeth of Bohemia (London, 1909), p. 107.

- ^ Nadine Akkerman, The Correspondence of Elizabeth Stuart Queen of Bohemia, vol. 2 (Oxford, 2011), p. 1119.

- ^ Nadine Akkerman, Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Hearts (Oxford, 2021), pp. 113-4: HMC Downshire, vol. 5 (London, 1988), p. 379 nos. 784, 786, 787.

- ^ See the Countess of Home's will, "Will of Maria Soton, Countess of Home", The National Archives Prob/11/272/611 ff. 403-6, and National Library of Scotland MS. 14547: A receipt for the purse is among the papers of the Earls of Moray.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch