History of Armenia

| History of Armenia |

|---|

|

| Timeline • Origins • Etymology |

The history of Armenia covers the topics related to the history of the Republic of Armenia, as well as the Armenian people, the Armenian language, and the regions of Eurasia historically and geographically considered Armenian.[1]

Armenia is located between Eastern Anatolia and the Armenian highlands,[1] surrounding the Biblical mountains of Ararat. The endonym of the Armenians is hay, and the old Armenian name for the country is Hayk' (Armenian: Հայք, which also means "Armenians" in Classical Armenian), later Hayastan (Armenian: Հայաստան).[1] Armenians traditionally associate this name with the legendary progenitor of the Armenian people, Hayk. The names Armenia and Armenian are exonyms, first attested in the Behistun Inscription of Darius the Great. The early Armenian historian Movses Khorenatsi derived the name Armenia from Aramaneak, the eldest son of the legendary Hayk.[2] Various theories exist about the origin of the endonym and exonyms of Armenia and Armenians (see Name of Armenia).

In the Bronze Age, several states flourished in the Armenian highlands, including the Hittite Empire (at the height of its power), Mitanni (southwestern historical Armenia), and Hayasa-Azzi (1600–1200 BC). Soon after the Hayasa-Azzi were the Nairi tribal confederation (1400–1000 BC) and the Kingdom of Urartu (1000–600 BC). Each of the aforementioned nations and tribes participated in the ethnogenesis of the Armenian people.[3][4] Yerevan, the modern capital of Armenia, dates back to the 8th century BC, with the founding of the fortress of Erebuni in 782 BC by King Argishti I at the western extreme of the Ararat plain.[5] Erebuni has been described as "designed as a great administrative and religious centre, a fully royal capital."[6]

The Iron Age kingdom of Urartu was replaced by the Orontid dynasty, which ruled Armenia first as satraps under Achaemenid Persian rule and later as independent kings.[7][8] Following Persian and subsequent Macedonian rule, the Kingdom of Greater Armenia was established in 190 BC by Artaxias I, founder of the Artaxiad dynasty. The Kingdom of Armenia rose to the peak of its influence in the 1st century BC under Tigranes the Great before falling under Roman suzerainty.[9] In the 1st century AD, a branch of the ruling Arsacid dynasty of the Parthian Empire established itself on the throne of Armenia.

In the early 4th century, Arsacid Armenia became the first state to accept Christianity as its state religion. The Armenians later fell under Byzantine, Sassanid Persian, and Islamic hegemony, but reinstated their independence with the Bagratid kingdom of Armenia in the 9th century. After the fall of the kingdom in 1045, and the subsequent Seljuk conquest of Armenia in 1064, the Armenians established a kingdom in Cilicia, which existed until its destruction in 1375.[10]

In the early 16th century, much of Armenia came under Safavid Persian rule; however, over the centuries Western Armenia fell under Ottoman rule, while Eastern Armenia remained under Persian rule.[11] By the 19th century, Eastern Armenia was conquered by Russia and Greater Armenia was divided between the Ottoman and Russian empires.[12]

In the early 20th century, the Ottoman government subjected the Armenians to a genocide in which up to 1.5 million Armenians were killed and many more were dispersed throughout the world via Syria and Lebanon. In 1918, an independent Republic of Armenia was established in Eastern Armenia in the wake of the collapse of the Russian Empire. This republic fell under Soviet rule in 1920, and Armenia became a republic within the Soviet Union after its founding. In 1991, with the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the modern-day independent Republic of Armenia was established.[13][14][15]

Prehistory

Stone tools from 325,000 years ago have been found in Armenia which indicate the presence of early humans at this time.[16]

In the 1960s, excavations in the Yerevan 1 Cave uncovered evidence of ancient human habitation, including the remains of a 48,000-year-old heart, and a human cranial fragment and tooth of a similar age.[citation needed]

The Armenian Highland shows traces of settlement from the Neolithic era. Archaeological surveys in 2010 and 2011 have resulted in the discovery of the world's earliest known leather shoe (3,500 BC), straw skirt (3,900 BC), and wine-making facility (4,000 BC) at the Areni-1 cave complex.[17][18][19]

The Shulaveri-Shomu culture of the central Transcaucasus region is one of the earliest known prehistoric cultures in the area, carbon-dated to roughly 6000–4000 BC.[citation needed]

Bronze Age

An early Bronze-Age culture in the area is the Kura-Araxes culture, assigned to the period between c. 4000 and 2200 BC. The earliest evidence for this culture is found on the Ararat plain; thence it spread to Georgia by 3000 BC (but never reaching Colchis), proceeding westward and to the south-east into an area below the Urmia basin and Lake Van.

From 2200 BC to 1600 BC, the Trialeti-Vanadzor culture flourished in Armenia, southern Georgia, and northeastern Turkey.[20][21] It has been speculated that this was an Indo-European culture.[22][23][24] Other, possibly related, cultures were spread throughout the Armenia Highlands during this time, namely in the Aragats and Lake Sevan regions.[25][26][27]

Early 20th-century scholars suggested that the name "Armenia" may have possibly been recorded for the first time on an inscription which mentions Armanî (or Armânum) together with Ibla, from territories conquered by Naram-Sin (2300 BC) identified with an Akkadian colony in the current region of Diyarbekir; however, the precise locations of both Armani and Ibla are unclear. Some modern researchers have placed Armani (Armi) in the general area of modern Samsat,[28] and have suggested it was populated, at least partially, by an early Indo-European-speaking people.[29] Today, the modern Assyrians (who traditionally speak Neo-Aramaic, not Akkadian) refer to the Armenians by the name Armani.[30] It is possible that the name Armenia originates in Armini, Urartian for "inhabitant of Arme" or "Armean country."[31] The Arme tribe of Urartian texts may have been the Urumu, who in the 12th century BC attempted to invade Assyria from the north with their allies the Mushki and the Kaskians. The Urumu apparently settled in the vicinity of Sason, lending their name to the regions of Arme and the nearby land of Urme.[32] Thutmose III of Egypt, in the 33rd year of his reign (1446 BC), mentioned as the people of "Ermenen", claiming that in their land "heaven rests upon its four pillars".[33] Armenia is possibly connected to Mannaea, which may be identical to the region of Minni mentioned in the Bible. However, what all these attestations refer to cannot be determined with certainty, and the earliest certain attestation of the name "Armenia" comes from the Behistun Inscription (c. 500 BC).

The earliest form of the word "Hayastan", an endonym for Armenia, might possibly be Hayasa-Azzi, a kingdom in the Armenian Highlands that was recorded in Hittite records dating from 1500 to 1200 BC.

Between 1200 and 800 BC, much of Armenia was united under a confederation of tribes, which Assyrian sources called Nairi ("Land of Rivers" in Assyrian").[34]

Iron Age

The Kingdom of Urartu, also known as the Kingdom of Van, flourished between the 9th century BC[35] and 585 BC[36] in the Armenian Highland. The founder of the Urartian Kingdom, Aramé, united all the principalities of the Armenian Highland and gave himself the title "King of Kings", the traditional title of Urartian Kings.[37] The Urartians established their sovereignty over all of Taron and Vaspurakan. The main rival of Urartu was the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[38]

During the reign of Sarduri I (834–828 BC), Urartu had become a strong and organized state, and imposed taxes on neighbouring tribes. Sarduri made Tushpa (modern Van) the capital of Urartu. His son, Ishpuinis, extended the borders of the state by conquering what would later be known as the Tigranocerta area and by reaching Urmia. Menuas (810–785 BC) extended the Urartian territory up north, by spreading towards the Araratian fields. He left more than 90 inscriptions by using the Mesopotamian cuneiform writing system in the Urartian language. Argishti I of Urartu conquered Latakia from the Hittites, and reached Byblos, and Phoenicia.[39] He built the Erebuni Fortress, located in modern-day Yerevan, in 782 BC by using 6600 prisoners of war.[40][41]

In 714 BC, the Assyrians under Sargon II defeated the Urartian king Rusa I at Lake Urmia and destroyed the holy Urartian temple at Musasir. At the same time, an Indo-European tribe called the Cimmerians attacked Urartu from the north-west region and destroyed the rest of his armies. Under Ashurbanipal (669–627 BC) the boundaries of the Assyrian Empire reached as far as Armenia and the Caucasus Mountains. The Medes under Cyaxares invaded Assyria later on in 612 BC, and then took over the Urartian capital of Van towards 585 BC, effectively ending the sovereignty of Urartu.[42] According to the Armenian tradition, the Medes helped the Armenians establish the Orontid dynasty.[43]

Antiquity

Orontid dynasty

After the fall of Urartu around 585 BC, the Satrapy of Armenia arose, ruled by the Armenian Orontid dynasty, which governed the state in 585–190 BC. Under the Orontids, Armenia during this era was a satrapy of the Persian Empire, and after its disintegration (in 330 BC), it became an independent kingdom. During the rule of the Orontid dynasty, most Armenians adopted the Zoroastrian religion.[44]

Artaxiad dynasty

The Hellenistic Seleucid Empire, controlled Syria, Armenia, and vast other eastern regions. However, after their defeat by Rome in 190 BC, the Seleucids relinquished control of any regional claim past the Taurus Mountains, limiting Seleucids to a quickly diminishing area of Syria. A Hellenistic Armenian state was founded in 190 BC. It was a Hellenistic successor state of Alexander the Great's short-lived empire, with Artaxias becoming its first king and the founder of the Artaxiad dynasty (190 BC–AD 1). At the same time, a western portion of the kingdom split as a separate state under Zariadris, which became known as Lesser Armenia while the main kingdom acquired the name of Greater Armenia.[36]

The new kings began a program of expansion which was to reach its zenith a century later. Their acquisitions are summarized by Strabo. Zariadris acquired Acilisene and the "country around the Antitaurus", possibly the district of Muzur or west of the Euphrates. Artaxias took lands from the Medes, Iberians, and Syrians. He then had confrontations with Pontus, Seleucid Syria and Cappadocia, and was included in the treaty which followed the victory of a group of Anatolian kings over Pharnaces of Pontus in 181 BC. Pharnaces thus abandoned all of his gains in the west.[45]

At its zenith, from 95 to 66 BC, Greater Armenia extended its rule over parts of the Caucasus and the area that is now eastern and central Turkey, north-western Iran, Israel, Syria and Lebanon, forming the second Armenian empire. For a time, Armenia was one of the most powerful states east of Rome. It eventually confronted the Roman Republic in wars, which it lost in 66 BC, but nonetheless preserved its sovereignty. Tigranes continued to rule Armenia as an ally of Rome until his death in 55 BC.[46]

The Third Mithridatic War and defeat of the King of Pontus by Roman Pompeius resulted in the Kingdom of Armenia becoming an allied client state of Rome. Later on, in 1 AD, Armenia came under full Roman control until the establishment of the Armenian Arsacid dynasty. The Armenian people then adopted a Western political, philosophical, and religious orientation. According to Strabo, around this time everyone in Armenia spoke "the same language."[47]

Roman Armenia

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2015) |

From Pompeius' campaign Armenia was, for the next few centuries, contested between Rome and Parthia/Sassanid Persia on the other hand. Roman emperor Trajan even created a short-lived Province of Armenia between 114 and 118 AD.[48]

Indeed, Roman supremacy was fully established by the campaigns of Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo,[49] that ended with a formal compromise: a Parthian prince of the Arsacid line would henceforth sit on the Armenian throne, but his nomination had to be approved by the Roman emperor.

Because this agreement was not respected by the Parthian Empire, in 114 Trajan from Antiochia in Syria marched on Armenia and conquered the capital Artaxata.[50][51] Trajan then deposed the Armenian king Parthamasiris (imposed by the Parthians) and ordered the annexation of Armenia to the Roman Empire as a new province. The new province reached the shores of the Caspian Sea and bordered to the north with Caucasian Iberia and Caucasian Albania, two vassal states of Rome. As a Roman province Armenia was administered by Catilius Severus of the Gens Claudia. After Trajan's death, however, his successor Hadrian decided not to maintain the province of Armenia. In 118 AD, Hadrian gave Armenia up, and installed Parthamaspates as its "vassal" king.

Arsacid dynasty

Armenia, under its Arshakuni dynasty, which was a branch of the eponymous Arsacid dynasty of Parthia, was often a focus of contention between Rome and Parthia.[52] The Parthians forced Armenia into submission from 37 to 47, when the Romans retook control of the kingdom.

Under Nero, the Romans fought a campaign (55–63) against the Parthian Empire, which had invaded the kingdom of Armenia, allied to the Romans. After gaining (60) and losing (62) Armenia, the Romans under Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo, legate of Syria entered (63) into an agreement of Vologases I of Parthia, which confirmed Tiridates I as king of Armenia, thus founding the Arshakuni dynasty.

The Arsacid dynasty lost control of Armenia for a few years when emperor Trajan created the "Roman Province of Armenia", fully included into the Roman Empire from 114 to 117 AD. His successor, Hadrian, reinstalled the Arsacid dynasty when he nominated Parthamaspates as "vassal" king of Armenia in 118 AD.

Another campaign was led by Emperor Lucius Verus in 162–165, after Vologases IV of Parthia had invaded Armenia and installed his chief general on its throne. To counter the Parthian threat, Verus set out for the east. His army won significant victories and retook the capital. Sohaemus, a Roman citizen of Armenian heritage, was installed as the new client king.[53]

The Sassanid Persians occupied Armenia in 252 and held it until the Romans returned in 287. In 384 the kingdom was split between the Byzantine Empire and the Persians.[54] Western Armenia quickly became a province of the Roman Empire under the name of Armenia Minor; Eastern Armenia remained a kingdom within Persia until 428, when the local nobility overthrew the king, and the Sassanids installed a governor in his place.

According to tradition, the Armenian Apostolic Church was established by two of Jesus' twelve apostles—Thaddaeus and Bartholomew—who preached Christianity in Armenia in the 40s–60s AD.[55] Between 1st and 4th centuries AD, the Armenian Church was headed by patriarchs.

Christianization

In 301, Armenia became the first nation to adopt Christianity as a state religion,[59] amidst the long-lasting geo-political rivalry over the region. It established a church that today exists independently of both the Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox churches, having become so in 451 after having rejected the Council of Chalcedon.[60] The Armenian Apostolic Church is a part of the Oriental Orthodox communion, not to be confused with the Eastern Orthodox communion. The first Catholicos of the Armenian church was Saint Gregory the Illuminator.[61] Because of his beliefs, he was persecuted by the pagan king of Armenia, and was "punished" by being thrown in Khor Virap, in modern-day Armenia.[62]

He acquired the title of Illuminator, because he illuminated the spirits of Armenians by introducing Christianity to them. Before this, the dominant religion amongst the Armenians was Zoroastrianism.[63] Scholars have suggested that Armenia adopted Christianity "partly . . . in defiance" of the Sassanids.[64]

In 405–06, Armenia's political future seemed uncertain. With the help of the king of Armenia, Mesrop Mashtots created a unique alphabet to suit the people's needs.[clarification needed][65] By doing so, he ushered in a new Golden Age and strengthened Armenian national identity.[66]

After years of rule, the Arsacid dynasty fell in 428, with Eastern Armenia being subjugated to Persia and Western Armenia, to Rome. In the 5th century, the Sassanid Shah Yazdegerd II tried to tie his Christian Armenian subjects more closely to the Sassanid Empire by reimposing the Zoroastrian religion.[67] The Armenians greatly resented this, and as a result, a rebellion broke out with Vartan Mamikonian as the leader of the rebels. Yazdegerd thus massed his army and sent it to Armenia, where the Battle of Avarayr took place in 451. The 66,000 Armenian rebels,[68] mostly peasants, lost their morale when Mamikonian died in the battlefield. They were substantially outnumbered by the 180,000- to 220,000-strong[69] Persian army of Immortals and war elephants. Despite being a military defeat, the Battle of Avarayr and the subsequent guerilla war in Armenia eventually resulted in the Treaty of Nvarsak (484), which guaranteed religious freedom to the Armenians.[70]

Persian Armenia

With the partition of Armenia in 387 by the Byzantines and Sassanids, the western half became part of the Byzantines known as Byzantine Armenia, while the eastern (and much larger half) became a vassal state within the Sassanid realm.[71]

In 428, the Arsacid dynasty of Armenia was completely abolished by the Sassanid Persians, and the territory was made a full province within Persia, known as Persian Armenia.[71] Persian Armenia remained in Sassanid hands up to the Muslim conquest of Persia, when the invading Muslim forces annexed the Sassanid realm.[72]

Middle Ages

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2015) |

Arab caliphates, Byzantium and Bagratid Armenia

In 591, the Byzantine emperor Maurice defeated the Persians and recovered much of the remaining territory of Armenia into the empire.[73] The conquest was completed by the emperor Heraclius, himself ethnically Armenian,[74][75][76] in 629. In 645, the Muslim Arab armies of the caliphate had attacked and conquered the country. Armenia, which once had its own rulers and was at other times under Persian and Byzantine control, passed largely into the power of the caliphs, and established the province of Arminiya.

Nonetheless, there were still parts of Armenia held within the empire, containing many Armenians. This population held tremendous power within the empire. Emperor Heraclius (610–641) was of Armenian descent, as was Emperor Philippikos Bardanes (711–713). The emperor Basil I, who took the Byzantine throne in 867, was the first of what is sometimes called the Armenian dynasty (see Macedonian dynasty), reflecting the strong effect the Armenians had on the Byzantine Empire.[77]

Evolving as a feudal kingdom in the ninth century, Armenia experienced a brief cultural, political and economic renewal under the Bagratuni dynasty. Bagratid Armenia was eventually recognized as a sovereign kingdom by the two major powers in the region: Baghdad in 885, and Constantinople in 886. Ani, the new Armenian capital, was constructed at the kingdom's apogee in 964.[78]

Sallarid dynasty

The Iranian[79][80] Sallarid dynasty conquered parts of Eastern Armenia in the second half of the 10th century.[81]

Seljuq Armenia

Although the native Bagratuni dynasty was founded under favourable circumstances, the feudal system gradually weakened the country by eroding loyalty to the central government. Thus internally enfeebled, Armenia proved an easy victim for the Byzantines, who captured Ani in 1045. The Seljuk dynasty under Alp Arslan in turn took the city in 1064.[83]

In 1071, after the defeat of the Byzantine forces by the Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Manzikert, the Turks captured the rest of Greater Armenia and much of Anatolia.[84] So ended Christian leadership of Armenia for the next millennium with the exception of a period of the late 12th-early 13th centuries, when the Muslim power in Greater Armenia was seriously troubled by the resurgent Kingdom of Georgia. Many local nobles (nakharars) joined their efforts with the Georgians, leading to liberation of several areas in northern Armenia, which was ruled, under the authority of the Georgian crown, by the Zakarids-Mkhargrzeli, a prominent Armeno-Georgian noble family.

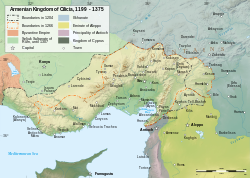

Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia

To escape death or servitude at the hands of those who had assassinated his relative Gagik II, King of Ani, an Armenian named Roupen with some of his countrymen went into the gorges of the Taurus Mountains and then into Tarsus of Cilicia. Here the Byzantine governor gave them shelter in the late 11th century. Two great dynastic families, the Rubenids and the Hethumids, ruled what became in 1199, with the coronation of Levon I, the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia and through skillful diplomacy and military alliances (explained below) maintained their political autonomy until 1375.[85] The kingdom's political independence relied on a vast network of castles which controlled the mountain passes and the strategic harbours.[86] Almost all of the civilian settlements were located directly below or near these fortifications.[87]

After the members of the first Crusade appeared in Asia Minor, the Armenians developed close ties to European Crusader States. They flourished in south-eastern Asia Minor until it was conquered by Muslim states. Count Baldwin, who with the rest of the Crusaders was passing through Asia Minor bound for Jerusalem, left the Crusader army and was adopted by Thoros of Edessa, an Armenian ruler of Greek Orthodox faith.[88] As they were hostile towards the Seljuks and unfriendly to the Byzantines, the Armenians took kindly to the crusader count. So when Thoros was assassinated, Baldwin was made ruler of the new crusader County of Edessa. It seems that the Armenians were pleased with Baldwin's rule and with the crusaders in general, and some number of them fought alongside the crusaders. When Antioch had been taken (1097), Constantine, the son of Roupen, received from the crusaders the title of baron.[89]

The Third Crusade and other events elsewhere left Cilicia as the sole substantial Christian presence in the Middle East.[88] World powers, such as Byzantium, the Holy Roman Empire, the papacy and even the Abbasid caliph competed and vied for influence over the state and each raced to be the first to recognise Leo II, Prince of Lesser Armenia, as the rightful king. As a result, he had been given a crown by both German and Byzantine emperors. Representatives from across Christendom and a number of Muslim states attended the coronation, thus highlighting the important stature that Cilicia had gained over time.[88] The Armenian authorities was often in touch with the crusaders. No doubt the Armenians aided in some of the other crusades. Cilicia flourished greatly under Armenian rule, as it became the last remnant of medieval Armenian statehood.[90] Cilicia acquired an Armenian identity, as the kings of Cilicia were called kings of the Armenians, not of the Cilicians.

In Lesser Armenia, Armenian culture was intertwined with both the European culture of the Crusaders and with the Hellenic culture of Cilicia. As the Catholic families extended their influence over Cilicia, the Pope wanted the Armenians to follow Catholicism. This situation divided the kingdom's inhabitants between pro-Catholic and pro-Apostolic camps. Armenian sovereignty lasted until 1375, when the Mamelukes of Egypt profited from the unstable situation in Lesser Armenia and destroyed it.[91]

Early modern period

Persian Armenia

Due to its strategic significance, the historical Armenian homelands of Western Armenia and Eastern Armenia were constantly fought over and passed back and forth between Safavid Persia and the Ottomans. For example, at the height of the Ottoman–Persian Wars, Yerevan changed hands fourteen times between 1513 and 1737. Greater Armenia was annexed in the early 16th century by Shah Ismail I.[92] Following the Peace of Amasya of 1555, Western Armenia fell into the neighbouring Ottoman hands, while Eastern Armenia stayed part of Safavid Iran, until the 19th century.[93]

In 1604, Shah Abbas I pursued a scorched-earth campaign against the Ottomans in the Ararat valley during the Ottoman–Safavid War (1603–1618). The old Armenian town of Julfa in the province of Nakhichevan was taken early in the invasion. From there Abbas' army fanned out across the Araratian plain. The Shah pursued a careful strategy, advancing and retreating as the occasion demanded, determined not to risk his enterprise in a direct confrontation with stronger enemy forces.

While laying siege to Kars, he learned of the approach of a large Ottoman army, commanded by Djghazadé Sinan Pasha. The order to withdraw was given; but to deny the enemy the potential to resupply themselves from the land, he ordered the wholesale destruction of the Armenian towns and farms on the plain. As part of this the whole population was ordered to accompany the Persian army in its withdrawal. Some 300,000 people were duly herded to the banks of the Araxes River. Those who attempted to resist the mass deportation were killed outright. The Shah had previously ordered the destruction of the only bridge, so people were forced into the waters, where a great many drowned, carried away by the currents, before reaching the opposite bank. This was only the beginning of their ordeal. One eye-witness, Father de Guyan, describes the predicament of the refugees thus:

- It was not only the winter cold that was causing torture and death to the deportees. The greatest suffering came from hunger. The provisions which the deportees had brought with them were soon consumed ... The children were crying for food or milk, none of which existed, because the women's breasts had dried up from hunger ... Many women, hungry and exhausted, would leave their famished children on the roadside, and continue their tortuous journey. Some would go to nearby forests in search of something to eat. Usually they would not come back. Often those who died, served as food for the living.

Unable to maintain his army on the desolate plain, Sinan Pasha was forced to winter in Van. Armies sent in pursuit of the Shah in 1605 were defeated, and by 1606 Abbas had regained all of the territory lost to the Turks earlier in his reign. The scorched-earth tactic had worked, though at a terrible cost to the Armenian people. Of the 300,000 deported it is calculated that less than half survived the march to Isfahan. In the conquered territories Abbas established the Erivan Khanate, a Muslim principality under the dominion of the Safavid Empire. Armenians formed less than 20% of its population[94] as a result of Shah Abbas I's deportation of many of the Armenian population from the Ararat valley and the surrounding region in 1605.[95]

An often-used policy by the Persians was the appointment of Turks as local rulers as so-called khans of their various khanates. These were counted as subordinate to the Persian Empire. Examples include: the Khanate of Erevan, Khanate of Nakhichevan and the Karabakh Khanate.

Even though Western Armenia had already once been conquered by the Ottomans following the Peace of Amasya, Greater Armenia was eventually decisively divided between the vying rivals, the Ottomans and the Safavids, in the first half of the 17th century following the Ottoman–Safavid War (1623–1639) and the resulting Treaty of Zuhab under which Eastern Armenia remained under Persian rule, and Western Armenia remained under Ottoman rule.[11]

Persia continued to rule Eastern Armenia, which included all of the modern-day Armenian Republic, until the first half of the 19th century. By the late 18th century, Imperial Russia had started to encroach to the south into the land of its neighbours; Qajar Iran and Ottoman Turkey. In 1804, Pavel Tsitsianov invaded the Iranian town of Ganja and massacred many of its inhabitants while making the rest flee deeper within the borders of Qajar Iran. This was a declaration of war and regarded as an invasion of Iranian territory.[96] It was the beginning of the Russo-Persian War (1804–1813). The following years were devastating for the Iranian towns in the Caucasus as well as the inhabitants of the region, as well as for the Persian army. The war eventually ended in 1813 with a Russian victory after their successful storming of Lankaran in early 1813. The Treaty of Gulistan that was signed in the same year forced Qajar Iran to irrevocably cede significant amounts of its Caucasian territories to Russia, comprising modern-day Dagestan, Georgia, and most of what is today the Republic of Azerbaijan.[97][98] Karabakh was also ceded to Russia by Persia.[98]

The Persians were severely dissatisfied with the outcome of the war which led to the ceding of so much Persian territory to the Russians. As a result,[99] the next war between Russia and Persia was inevitable, namely the Russo-Persian War (1826–1828). However, this war ended even more disastrously, as the Russians not only occupied as far as Tabriz, the ensuing treaty that followed, namely the Treaty of Turkmenchay of 1828, forced it to irrevocably cede its last remaining territories in the Caucasus, comprising all of modern-day Armenia, Nakhchivan and Iğdır Province.[100]

By 1828, Persia had lost Eastern Armenia, which included the territory of the modern-day Armenian Republic after centuries of rule. From 1828 until 1991, Eastern Armenia would enter a Russian dominated chapter. Following Russia's conquest of all of Qajar Iran's Caucasian territories, many Armenian families were encouraged to settle in the newly conquered Russian territories.[101]

Ottoman Armenia

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (December 2015) |

Mehmed II conquered Constantinople from the Byzantines in 1453 and made it the Ottoman Empire's capital. Mehmed and his successors used the religious systems of their subject nationalities as a method of population control, and so Ottoman Sultans invited an Armenian archbishop to establish the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople. The Armenians of Constantinople grew in numbers, and became respected, if not full, members of Ottoman society.

The Ottoman Empire ruled in accordance to Islamic law. As such, the People of the Book (the Christians and the Jews) had to pay an extra tax to fulfil their status as dhimmi and in return were guaranteed religious autonomy. While the Armenians of Constantinople benefited from the Sultan's support and grew to be a prospering community, the same could not be said about the ones inhabiting historic Armenia.

During times of crisis the ones in the remote regions of mountainous eastern Anatolia were mistreated by local Kurdish chiefs and feudal lords. They often also had to suffer (alongside the settled Muslim population) raids by nomadic Kurdish tribes.[102] Armenians, like the other Ottoman Christians (though not to the same extent), had to transfer some of their healthy male children to the Sultan's government due to the devşirme policies in place. The boys were then forced to convert to Islam (by threat of death otherwise) and educated to be fierce warriors in times of war, as well as Beys, Pashas and even Grand Viziers in times of peace.[citation needed]

The Armenian national liberation movement was the Armenian effort to free the historic Armenian homeland of eastern Anatolia and Transcaucasus from Russian and Ottoman domination and re-establish the independent Armenian state. The national liberation movement of the Balkan peoples and the immediate involvement of the European powers in the Eastern question had a powerful effect on the development of the national liberation ideology movement among the Armenians of the Ottoman Empire.[103]

The Armenian national movement, besides its individual heroes, was an organized activity represented around three parties of Armenian people, Social Democrat Hunchakian Party, Armenakan and Armenian Revolutionary Federation, which ARF was the largest and most influential among the three. Those Armenians who did not support national liberation aspirations or who were neutral were called chezoks. In 1839, the situation of the Ottoman Armenians slightly improved after Abdul Mejid I carried out Tanzimat reforms in its territories. However, later Sultans, such as Abdul Hamid II stopped the reforms and carried out massacres, now known as the Hamidian massacres of 1895–96 leading to a failed Armenian attempt to assassinate him.[104]

Russian Armenia

In the aftermath of the Russo-Persian War, 1826–1828, the parts of historic Armenia (also known as Eastern Armenia) under Persian control, centering on Yerevan and Lake Sevan, were incorporated into Russia after Qajar Persia's forced ceding in 1828 per the Treaty of Turkmenchay.[105] Under Russian rule, the area corresponding approximately to modern-day Armenian territory was called "Province of Yerevan". The Armenian subjects of the Russian Empire lived in relative safety, compared to their Ottoman kin, albeit clashes with Tatars and Kurds were frequent in the early 20th century.[citation needed] Even though Russian Armenians benefited from the advanced Russian culture, and greater access to European thought, and broader economic initiative, they were denied equal educational and administrative opportunities like many other racial and religious minorities.[106]

The Treaty of Turkmenchay of 1828 had further stipulated the rights of the Russian tsar to resettle Persian Armenians within the newly conquered Caucasus region, which had been taken over from Iran. Following the resettlement of Persian Armenians alone in the newly conquered Russian territories, significant demographic shifts were bound to take place. The Armenian-American historian George Bournoutian gives a summary of the ethnic make-up after those events:[107]

In the first quarter of the 19th century the Khanate of Erevan included most of Eastern Armenia and covered an area of approximately 7,000 square miles [18,000 km2]. The land was mountainous and dry, the population of about 100,000 was roughly 80 percent Muslim (Persian, Azeri, Kurdish) and 20 percent Christian (Armenian).

After the incorporation of the Erivan Khanate into the Russian Empire, Muslim majority of the area gradually changed, at first the Armenians who were left captive were encouraged to return.[108] As a result of which an estimated 57,000 Armenian refugees from Persia returned to the territory of the Erivan Khanate after 1828, while about 35,000 Muslims (Persians, Turkic groups, Kurds, Lezgis, etc.) out of a total population of over 100,000 left the region.[109]

20th century

The Armenian genocide (1915–1921) and First World War

In 1915, the Ottoman Empire systematically carried out the Armenian genocide. This genocide was preceded by a wave of massacres in the years 1894 to 1896,[104] as well as another massacre in 1909 in Adana. On 24 April 1915, Ottoman authorities rounded up, arrested, and deported 235 to 270 Armenian intellectuals and community leaders from Constantinople to the region of Ankara, where the majority were murdered. The genocide was carried out during and after World War I and implemented in two phases—the wholesale killing of the able-bodied male population through massacre and subjection of army conscripts to forced labour, followed by the deportation of women, children, the elderly, and the infirm on death marches leading to the Syrian Desert. Driven forward by military escorts, the deportees were deprived of food and water and subjected to periodic robbery, rape, and massacre.[110]

Most frequently, the exact number of deaths is estimated to have been 1.5 million,[111] with other estimates ranging from 800,000 to 1,800,000.[112][113][114]: 98 [115] These events are traditionally commemorated yearly on 24 April, the Armenian Christian martyr day.[116]

First Republic of Armenia (1918–1920)

Between the 4th and 19th centuries, the traditional area of Armenia was conquered and ruled by Persians, Byzantines, Arabs, Mongols, and Turks, among others. Parts of historical Armenia gained independence from the Ottoman Empire and the Russian Empire after the collapse of these two empires in the wake of the First World War.[117][118]

Transcaucasian Federation (1917–1918)

During the Russian Revolution, the provinces of the Caucasus seceded and formed their own federal state called the Transcaucasian Federation. Competing national interests and war with Turkey led to the dissolution of the republic half a year later, in April 1918.

After the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the takeover of the Bolsheviks, Stepan Shaumyan was placed in charge of Russian Armenia. In September 1917, the convention in Tiflis elected the Armenian National Council,[119] the first sovereign political body of Armenians since the collapse of Lesser Armenia in 1375. Meanwhile, both the Ittihad (Unionist) and the Nationalists moved to win the friendship of the Bolsheviks.

Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk) sent several delegations to Moscow in an attempt to win some support for his own post-Ottoman movement in what he saw as a modernised ethno-nationalist Turkey. This alliance proved disastrous for the Armenians. The signing of the Ottoman-Russian friendship treaty (1 January 1918) helped Vehib Pasha to attack the new republic. Under heavy pressure from the combined forces of the Ottoman army and the Kurdish irregulars, the Republic was forced to withdraw from Erzincan to Erzurum. In the end, the Republic had to evacuate Erzurum as well.

Further southeast, in Van, the Armenians resisted the Turkish army until April 1918, but eventually were forced to evacuate it and withdraw to Persia. Conditions deteriorated when Azerbaijani Tatars sided with the Turks and seized the Armenian's lines of communication, thus cutting off the Armenian National Councils in Baku and Yerevan from the National Council in Tiflis. The First Republic of Armenia was established on 28 May 1918.[119]

Georgian–Armenian War (1918)

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (December 2015) |

During the final stages of World War I, the Armenians and Georgians had been defending against the advance of the Ottoman Empire. In June 1918, to forestall an Ottoman advance on Tiflis, the Georgian troops had occupied the Lori Province which at the time had a 75% Armenian majority.[120]

After the Armistice of Mudros and the withdrawal of the Ottomans, the Georgian forces remained. The Georgian Menshevik parliamentarian Irakli Tsereteli suggested that the Armenians would be safer from the Turks as Georgian citizens. The Georgians offered a quadripartite conference comprising Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus to resolve the issue. The Armenians rejected this proposal. In December 1918, the Georgians were confronting a rebellion chiefly in the village of Uzunlar in the Lori region. Within days, hostilities commenced between the two republics.[120]

The Georgian–Armenian War was a border war fought in 1918 between the Democratic Republic of Georgia and the First Republic of Armenia over the then disputed provinces of Lori and Javakheti which had been historically bi-cultural Armenian-Georgian territories, but were largely populated by Armenians in the 19th century.[121]

Armenian-Azerbaijan War

A considerable degree of hostility existed between Armenia and its new neighbor to the east, the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan, stemming largely from racial, religious, cultural and societal differences. The Azeris had close ethnic and religious ties to the Turks and had provided material support for them in their drive to Baku in 1918. Although the borders of the two countries were still undefined, Azerbaijan claimed most of the territory Armenia was sitting on, demanding all or most parts of the former Russian provinces of Elizavetpol, Tiflis, Yerevan, Kars and Batum.[122] As diplomacy failed to accomplish compromise, even with the mediation of the commanders of a British expeditionary force that had installed itself in the Caucasus, territorial clashes between Armenia and Azerbaijan took place throughout 1919 and 1920, most notably in the regions of Nakhichevan, Karabakh, and Syunik (Zangezur). Repeated attempts to bring these provinces under Azerbaijani jurisdiction were met with fierce resistance by their Armenian inhabitants. In May 1919, Dro led an expeditionary unit that was successful in establishing Armenian administrative control in Nakhichevan.[123]

Paris Peace Conference

At Paris Peace Conference in 1919 it was proposed to create large (330,200 km2 or 127,491 sq mi) Armenian state, including the territory of former Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia with total population of 4.3 million, 2.5 million of which would be Armenians.[124]

Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres was signed between the Allied and Associated Powers and Ottoman Empire at Sèvres, France, on 10 August 1920. The treaty included a clause on Armenia: it made all parties signing the treaty recognize Armenia as a free and independent state. The drawing of definite borders was, however, left to U.S. president Woodrow Wilson and the United States State Department, and was only presented to Armenia on 22 November 1920. The new borders gave Armenia access to the Black Sea and awarded large portions of the eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire to the republic.[125]: 40–44

The Treaty of Sèvres was signed by the Ottoman government, but Sultan Mehmed VI never signed it and thus never came into effect. The Turkish Revolutionaries, led by Mustafa Kemal Pasha, began the Turkish National Movement which, in opposing any territorial concessions to either the Greeks or the Armenians.[citation needed]

Turkish and Soviet Invasion

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (December 2015) |

On 20 September 1920, Turkish nationalist militants invaded the region of Sarikamish.[126] In response, Armenia declared war on Turkey on 24 September and the Turkish invasion of Armenia (1920) began. In the regions of Oltu, Sarikamish, Kars, and Alexandropol (Gyumri), Armenian forces clashed with those of the Turkish armies. Mustafa Kemal Pasha had sent several delegations to Moscow in search of an alliance, where he had found a receptive response by the Soviet government, which started sending gold and weapons to the Turkish revolutionaries, which would prove disastrous for the Armenians.[127]

Armenia gave way to communist power in late 1920. In November 1920, the Turkish revolutionaries captured Alexandropol and were poised to move in on the capital. A cease fire was concluded on 18 November. Negotiations were then carried out between Kâzım Karabekir and a peace delegation led by Alexander Khatisian in Alexandropol; although Karabekir's terms were extremely harsh the Armenian delegation had little recourse but to agree to them. The Treaty of Alexandropol was signed on 3 December 1920, although the Armenian government had already fallen to the Soviets the day before.[128]

As the terms of defeat were being negotiated, Bolshevik Grigoriy Ordzhonikidze invaded from Azerbaijan the First Republic of Armenia to establish a new pro-Bolshevik government in the country. The 11th Red Army began its virtually unopposed advance into Armenia on 29 November 1920 at Ijevan. The actual transfer of power took place on 2 December 1920 in Yerevan.[129]

The Armenian leadership approved an ultimatum presented to it by the Soviet plenipotentiary Boris Legran. Armenia decided to join the Soviet sphere, while Soviet Russia agreed to protect its remaining territory from the advancing Turkish army. The Soviets also pledged to take steps to rebuild the army, protect the Armenians and to not pursue non-communist Armenians, although the final condition of this pledge was reneged when the Dashnaks were forced out of the country.[130]

On 5 December, the Armenian Revolutionary Committee (Revkom, made up of mostly Armenians from Azerbaijan) also entered the city.[131] Finally, on the following day, 6 December, Felix Dzerzhinsky's Cheka entered Yerevan, thus effectively ending the existence of the Democratic Republic of Armenia. At that point what was left of Armenia was under the influence of the Bolsheviks.[citation needed]

Although the Bolsheviks succeeded in ousting the Turks from their positions in Armenia, they decided to establish peace with Turkey. In 1921, the Bolsheviks and the Turks signed the Treaty of Kars, in which Turkey ceded Adjara to the USSR in exchange for the Kars territory (today the Turkish provinces of Kars, Surmalu, and Ardahan). The land given to Turkey included the ancient city of Ani and Mount Ararat, the spiritual Armenian homeland. In 1922, the newly proclaimed Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic, under the leadership of Alexander Miasnikyan, became part of the Soviet Union as one of three republics comprising the Transcaucasian SFSR.[129]

Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic (1922–1991)

The Transcaucasian SFSR was dissolved in 1936, and as a result Armenia became a constituent republic of the Soviet Union as the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic.[132] The transition to socialism was difficult for Armenia, and for most of the other republics in the Soviet Union. The Soviet authorities placed Armenians under supervision. The rate of freedom of speech was considered low, even less so during secretaryship of Joseph Stalin. Any individual who was suspected of using or introducing nationalist, racist and conservative rhetoric or elements in their works were labelled traitors or propagandists, and were sent to prisons in Siberia. Even Zabel Yesayan, a writer who was fortunate enough to escape from ethnic cleansing during the Armenian genocide, was quickly exiled to Siberia after returning to Armenia from France.

Armenian SSR participated in World War II by sending hundreds of thousands of soldiers to the front line to defend the USSR. Marxist–Leninist system had several positive aspects. Armenia benefited from the Soviet economy, especially when it was at its apex. Provincial villages gradually became towns and towns gradually became cities. Peace between Armenia and Azerbaijan was reached, albeit temporarily. During this time, Armenia had a sizeable Azeri minority, mostly centred in Yerevan. Likewise, Azerbaijan had an Armenian minority, concentrated in Baku and Kirovabad.

Many Armenians still had nationalist and conservative sentiments, even though they were discouraged from expressing them publicly. On 24 April 1965, tens of thousands of Armenians flooded the streets of Yerevan to remind the world of the horrors that their parents and grandparents endured during the Armenian genocide of 1915. This was the first public demonstration of such high numbers in the USSR, which defended national interests rather than collective ones. In the late 1980s, Armenia was suffering from pollution. With Mikhail Gorbachev's introduction of glasnost and perestroika, public demonstrations became more common. Thousands of Armenians demonstrated in Yerevan because of the USSR's inability to address simple ecological concerns. Later on, with the conflict in Karabakh, the demonstrations obtained a more nationalistic flavour. Many Armenians began to demand statehood.

In 1988, the Spitak earthquake killed tens of thousands of people and destroyed multiple towns in northern Armenia, such as Leninakan (modern-day Gyumri) and Spitak. Many families were left without electricity and running water. The harsh situation caused by the earthquake and subsequent events made many residents of Armenia leave and settle in North America, Western Europe and Australia.

On 20 February 1988, interethnic fighting between the ethnic Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijanis broke out shortly after the parliament of Nagorno-Karabakh, an autonomous oblast in Azerbaijan, voted to unify the region with Armenia. The First Nagorno-Karabakh War pitted Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh, backed by Armenia, against the Army of Azerbaijan.

Independent Armenia (from 1991)

Orange: areas overwhelmingly populated by Armenians (Republic of Armenia: 98%;[133] Nagorno-Karabakh: 99%; Javakheti: 95%)

Yellow: Historically Armenian areas with presently no or insignificant Armenian population (Western Armenia and Nakhichevan)

Armenia declared its independence from the Soviet Union on 23 August 1990.[134] Independence was confirmed by referendum on 21 September 1991. However, widespread recognition did not occur until the formal dissolution of the Soviet Union on 25 December 1991.

Armenia faced many challenges during its first years as a sovereign state. Several Armenian organizations from around the world quickly arrived to offer aid and to participate in the country's early years. From Canada, a group of young students and volunteers under the CYMA - Canadian Youth Mission to Armenia banner arrived in Ararat Region and became the first youth organization to contribute to the newly independent Republic.

Following the Armenian victory in the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, both Azerbaijan and Turkey closed their borders and imposed a blockade which they retain to this day, severely affecting the economy of the fledgling republic. In October 2009 Turkey and Armenia signed a treaty to normalize relations.

Ter-Petrosyan presidency (1991–1998)

Levon Ter-Petrosyan was popularly elected the first president of the newly independent Republic of Armenia on 16 October 1991 and re-elected on 22 September 1996.[135] His re-election was marred by allegations of electoral fraud reported by the opposition and supported by many international observers. His popularity waned further as the opposition started blaming him for the economic quagmire that Armenia's post-Soviet economy was in. He was also unpopular with one party in particular, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, which he banned and jailed on the grounds that the party had a foreign-based leadership—something which was forbidden according to the Armenian Constitution.

Ter-Petrosyan was forced to step down in February 1998 after advocating compromised settlement of the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh which many Armenians regarded as undermining their security. Ter-Petrosyan's key ministers, led by then-Prime Minister Robert Kocharyan, refused to accept a peace plan for Karabakh put forward by international mediators in September 1997. The plan, accepted by Ter-Petrosyan and Azerbaijan, called for a "phased" or "step-by-step" settlement of the conflict which would postpone an agreement on Nagorno-Karabakh's status, the main stumbling block. That agreement was to accompany the return of most Armenian-occupied Azerbaijani territories around Nagorno-Karabakh and the lifting of the Azerbaijani and Turkish blockades of Armenia.[citation needed] In January 1998, Ter-Petrosyan's ministers forced Ter-Petrosyan to resign.[136]

Kocharyan presidency (1998–2008)

After the resignation of his predecessor Levon Ter-Petrosyan, Robert Kocharyan was elected Armenia's second president on 30 March 1998, defeating his main rival, Karen Demirchyan, in an early presidential election marred by irregularities and violations by both sides as reported by international electoral observers. Complaints included that Kocharyan had not been an Armenian citizen for ten years as required by the constitution.[137] In early 1998, Kocharyan rejected the 1997 OSCE Minsk Group peace plan and initiated a new phase of Nagorno-Karabakh negotiations, where Heydar Aliyev and Kocharyan negotiated secret from their publics and senior officials. In 1999, they orally agreed to a land swap that would annex Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia in exchange for a strip of land connecting Azerbaijan and its exclave of Nakhichvan along the Iranian-Armenian border. In the fall of that year, Aliyev and Kocharyan informed the Minsk Group Co-Chairs of their plan and asked them to put it in writing.[136]

Weeks later, several opposition leaders in the Armenian Parliament and the Prime Minister of Armenia were killed by gunmen in an episode known as the 1999 Armenian parliament shooting. Kocharyan himself negotiated with terrorists to lease the MP hostages. It is widely believed by Armenians at large that Kocharyan is responsible for the parliament shooting.[138][139] Thereafter, Kocharyan informed the Minsk Group that he was not able to support the peace deal anymore.[136]

The 2003 Armenian presidential election were held on 19 February and on 5 March 2003. No candidate received a majority in the first round of the election with the incumbent president Kocharyan winning slightly under 50% of the vote. Therefore, a second round was held and Kocharyan defeated Stepan Demirchyan with official results showed him winning just over 67% of the vote. In both rounds, electoral observers from the OSCE reported significant amounts of electoral fraud by Demirchyan's supporters and numerous supporters of Demirchyan were arrested before the second round took place.[140]

Demirchyan described the election as having been rigged and called on his supporters to rally against the results.[141] Tens of thousands of Armenians protested in the days after the election against the results and called on President Kocharyan to step down.[140] Kocharyan was sworn in for a second term in early April and the constitutional court upheld the election, while recommending that a referendum be held within a year to confirm the election result.[13][14]

As president, Kocharyan continued to negotiate a peaceful resolution with Azerbaijani president Ilham Aliyev on the status of Nagorno-Karabakh. Talks between Aliyev and Kocharyan were held in September 2004 in Astana, Kazakhstan, on the sidelines of the CIS summit. Reportedly, one of the suggestions put forward was the withdrawal of Armenian forces from the Azeri territories adjacent to Nagorno-Karabakh, and holding referendums (plebiscites) in Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijan proper regarding the future status of the region. On 10–11 February 2006, Kocharyan and Aliyev met in Rambouillet, France to discuss the fundamental principles of a settlement to the conflict, including the withdrawal of troops, formation of international peace keeping troops, and the status of Nagorno-Karabakh.[142]

Contrary to the initial optimism, the Rambouillet talks did not produce any agreement, with key issues such as the status of Nagorno-Karabakh and whether Armenian troops would withdraw from Kalbajar still being contentious. The next session of the talks was held in March 2006 in Washington, D.C.[142] Russian president Vladimir Putin applied pressure to both parties to settle the disputes.[143] No progress arose from further meetings in Minsk and Moscow in November 2006.[144]

Sargsyan presidency (2008–2018)

Serzh Sargsyan, then Prime Minister of Armenia and having President Kocharyan's backing, was viewed as the strongest contender for the post of President of Armenia in the February 2008 presidential election.[145][146]

Ter-Petrosyan officially announced his candidacy in the 2008 presidential election in a speech in Yerevan on 26 October 2007. He accused Kocharyan's government of massive corruption, involving the theft of "at least three to four billion dollars" over the previous five years. He was critical of the government's claims of strong economic growth and argued that Kocharyan and his Prime Minister, Serzh Sargsyan, had come to accept a solution to the problem of Nagorno-Karabakh that was effectively the same solution that he had proposed ten years earlier. A number of opposition parties have rallied behind him since his return to the political arena, including the People's Party of Armenia, led by Stepan Demirchyan; the Armenian Republic Party, led by Aram Sargsyan;[147] the Social Democrat Hunchakian Party; Azadakrum, led by Jirair Sefilian; the New Times Party; and the Heritage Party, led by Raffi Hovannisian.[148]

Final results from the election, which was held on 19 February 2008, officially showed Sargsyan winning about 53% of the vote, and Ter-Petrosyan in second place with 21.5% of the vote.[149]

Ter-Petrosyan and his supporters accused the government of rigging the election and claimed victory;[150] beginning 20 February, he led continuous protests involving tens of thousands of his supporters in Yerevan.[151]

On the early morning of 1 March, reportedly acting on evidence of firearms in the camp, the authorities moved in to inspect the tents set up by demonstrators. Law enforcement agents then violently dispersed the hundreds of protestors camped in. Ter-Petrosyan was placed under de facto house arrest, not being allowed to leave his home, though the authorities later denied the allegations.[152]

A few hours later, tens of thousands of protestors or more gathered at Miyasnikyan Square to protest the government's act. Police, overwhelmed by the sheer size of the crowd, pulled out. A state of emergency was implemented by President Kocharyan at 5 pm, allowing the army to be moved into the capital. By nightfall, a few thousand protesters had barricaded themselves using commandeered municipal buses. As a result of skirmishes with the police, ten people died, including policemen.[153][154]

This was followed by mass arrests and purges of prominent members of the opposition, as well as a de facto ban on any further anti-government protests. Sargsyan was recognized as legitimate president[155][156]

On 10 October 2009, the Turkish-Armenian protocols on the establishment of diplomatic relations constituted a novelty in Turkish-Armenian relations. Sargsyan accepted the proposal of studying the issue of the Armenian genocide through a commission, and recognized the current Turkish-Armenian border. In 2009–10, the Azerbaijan's military build-up along with increasing war rhetoric and threats risked causing renewed problems in the South Caucasus.[157]

In 2011, protests erupted in Armenia as part of the revolutionary wave sweeping through the Middle East. Protesters continue to demand an investigation into the 2008 violence, the release of political prisoners, an improvement in socioeconomic conditions, and the institution of democratic reforms. The Armenian National Congress and Heritage have been influential in organizing and leading protests.[158]

Between 1 and 5 April 2016, there were renewed clashes between Armenian and Azerbaijani armed forces. (see 2016 Armenian–Azerbaijani clashes).

In March 2018, Sargsyan was re-elected Prime Minister, despite opposition protests.[159] After military forces joined the protests on 23 April, Sargsyan resigned his position.[160][161] Former Prime Minister Karen Karapetyan succeeded Sargsyan as acting Prime Minister.

Nikol Pashinyan premiership (2018–present)

In March 2018, Armenian parliament elected Armen Sarkissian as the new president of Armenia. The controversial constitutional reform to reduce presidential power was implemented, while the authority of the prime minister was strengthened.[162] In May 2018, parliament elected opposition leader Nikol Pashinyan as the new prime minister. His predecessor Serzh Sargsyan resigned two weeks earlier following widespread anti-government demonstrations.[163]

On 27 September 2020, a full-scale war erupted due to the unresolved Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Both the armed forces of Armenia and Azerbaijan reported military and civilian casualties.[164] A ceasefire agreement was signed on 10 November, in which the occupied territories surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh were handed over to Azerbaijan. Protests were held in Armenia over this and hundreds stormed the Parliament building in Yerevan. Protests continued throughout November, with demonstrations in Yerevan and other cities demanding the resignation of Pashinyan.[165]

On 25 February 2021, The Armenian military called for Pashinyan to resign. The declaration, which Pashinyan described as a coup attempt, caused a political crisis that ended with the Chief of the General Staff of the Armenian Armed Forces Onik Gasparyan's dismissal.[166][167] On 25 April 2021, Pashinyan announced his formal resignation from his post of prime minister to allow snap parliamentary elections in June. He continued to act as interim prime minister in the leadup to the election.[168] His party won the 2021 election, receiving more than half of all votes. Nikol Pashinyan was officially appointed Armenia's prime minister.[169] On 23 January 2022, Armen Sarkissian left the office, saying the constitution does not any more give the president sufficient powers to influence.[170] On 3 March 2022, Vahagn Khachaturyan was elected as the fifth president of Armenia in the second round of parliamentary vote.[171]

See also

- Armenian resistance during the Armenian genocide

- Dissolution of the Soviet Union

- History of Georgia (country)

- History of Iran

- History of Nagorno-Karabakh

- History of Russia

- History of the Caucasus

- History of Western Asia

- List of Armenian Kings

- List of Armenian territories and states

- List of Patriarchs of Armenia

- Politics of Armenia

- President of Armenia

- Timeline of Armenian history

- Timeline of Armenian national movement

- Timeline of modern Armenian history

- Zakarid Armenia

References

Citations

- ^ a b c "Armenian Rarities Collection". www.loc.gov. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. 2020. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

The lands of the Armenians were for millennia located in Eastern Anatolia, on the Armenian Highlands, and into the Caucasus Mountain range. First mentioned almost contemporaneously by a Greek and Persian source in the 6th century BC, modern DNA studies have shown that the people themselves had already been in place for many millennia. Those people the world know as Armenians call themselves Hay and their country Hayots' ashkharh–the land of the Armenians, today known as Hayastan. Their language, Hayeren (Armenian) constitutes a separate and unique branch of the Indo-European linguistic family tree. A spoken language until Christianity became the state religion in 314 AD, a unique alphabet was created for it in 407, both for the propagation of the new faith and to avoid assimilation into the Persian literary world.

- ^ Moses of Chorene,The History of Armenia, Book 1, Ch. 12 (in Russian)

- ^ Kurkjian, Vahan (196). History of Armenia. Michigan.

- ^ Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia, v. 12, Yerevan 1987; Artak Movsisyan "Sacred Highland: Armenia in the spiritual conception of the Near East", Yerevan, 2000.

- ^ Katsenelinboĭgen, Aron (1990). The Soviet Union: Empire, Nation and Systems. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. p. 143. ISBN 0-88738-332-7.

- ^ R.D. Barnett (1982). "Urartu". In John Boardman; I.E.S. Edwards; N.G.L. Hammond; E. Sollberger (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History, Vol. 3, Part 1: The Prehistory of the Balkans, the Aegean World, Tenth to Eighth Centuries BC (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 346. ISBN 978-0521224963.

- ^ Toumanoff, Cyril (1963). Studies in Christian Caucasian history. Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press. pp. 278ff.

- ^ Tiratsyan, Gevorg. «Երվանդունիներ» (Yerevanduniner). Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia. vol. iii. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1977, p. 640. (in Armenian)

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G. (2004). The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume I: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiquity to the Fourteenth Century. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 49. ISBN 1-4039-6421-1.

- ^ "Landmarks in Armenian history". Internet Archive. Retrieved 22 June 2010. "1080 A.D. Rhupen, cousin of the Bagratonian kings, sets up on Mount Taurus (overlooking the Mediterranean Sea) the kingdom of New Armenia which lasts 300 years."

- ^ a b Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia 2003. Taylor & Francis. 2000. ISBN 9781857431377. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ Peimani, Hooman (2009). Conflict and Security in Central Asia and the Caucasus. Abc-Clio. ISBN 9781598840544. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ a b "Armenia: President Sworn in Amid Protests". The New York Times. 10 April 2003. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ^ a b "Constitutional court stirs Armenian political controversy". Eurasianet.org. 23 April 2003. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ^ Croissant, Michael P. (1998). The Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict: Causes and Implications. London: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-96241-8.

- ^ "Stone Tool Discovery in Armenia Gives Insight into Human Innovation 325,000 Years Ago". sci-news.com. 27 September 2014.

- ^ "The first leather shoe". CNN. Archived from the original on 26 September 2010. Retrieved 15 November 2007.

- ^ "5,900-year-old women's skirt discovered in Armenian cave". News Armenia. 13 September 2011. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ^ "The first wine-making facility in Armenia". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 12 January 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2007.

- ^ Joan Aruz, Sarah B. Graff, Yelena Rakic, Cultures in Contact: From Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C. The Metropolitan Museum of art symposia. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013 ISBN 1588394751 pp. 12-24

- ^ Aynur Özifirat (2008), The Highland Plateau of Eastern Anatolia in the Second Millennium BC: Middle/Late Bronze Ages pp.103–106

- ^ John A. C. Greppin and I. M. Diakonoff, Some Effects of the Hurro-Urartian People and Their Languages upon the Earliest Armenians Journal of the American Oriental Society Vol. 111, No. 4 (Oct. – Dec. 1991), pp. 721 [1]

- ^ Joan Aruz, Kim Benzel, Jean M. Evans, Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.)[2] (2008) pp. 92

- ^ Kossian, Aram V. (1997), The Mushki Problem Reconsidered pp. 254

- ^ Daniel T. Potts A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. Volume 94 of Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World. John Wiley & Sons, 2012 ISBN 1405189886 p. 681

- ^ Simonyan, Hakob Y. (2012). "New Discoveries at Verin Naver, Armenia". Backdirt (The Puzzle of the Mayan Calendar). The Cotsen Institute of Archaeology at UCLA: 110–113.

- ^ Martirosyan, Hrach (2014). "Origins and Historical Development of the Armenian Language" (PDF). Leiden University. pp. 1–23. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Archi, Alfonso (2016). "Egypt or Iran in the Ebla Texts?". Orientalia. 85: 3.

- ^ Kroonen, Guus; Gojko Barjamovic; Michaël Peyrot (9 May 2018). "Linguistic supplement to Damgaard et al. 2018: Early Indo-European languages, Anatolian, Tocharian and Indo-Iranian". Zenodo: 3. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1240524.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Martiros Kavoukjian, "The Genesis of Armenian People", Montreal, 1982.

- ^ Armen Petrosyan. The Indo-European and Ancient Near Eastern Sources of the Armenian Epic. Journal of Indo-European Studies. Institute for the Study of Man. 2002. p. 184. [3]

- ^ Armen Petrosyan. The Indo-European and Ancient Near Eastern Sources of the Armenian Epic. Journal of Indo-European Studies. Institute for the Study of Man. 2002. pp. 166-167. [4]

- ^ International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, 1915 [5] Archived 21 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine; Eric H. Cline and David O'Connor (eds.) Thutmose III, University of Michigan, 2006; ISBN 978-0-472-11467-2.

- ^ "The Longest Rivers in Armenia". 21 December 2020.

- ^ "Ancient Near East Chronology". Archived from the original on 19 February 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- ^ a b "Urartu/Armenia". Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- ^ "Transanatolie – Kings of Urartu". Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- ^ "ArcImaging (Archeological Imaging Research Consortium)". Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- ^ Dubov, Kalman (26 November 2021). Journey to the Republic of Armenia. Kalman Dubov.

- ^ Piotrovsky, Boris (1 January 1975). From the Lands of Scythians: Ancient Treasures from the Museums of the U.S.S.R., 3000 B.C.–100 B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 15.

- ^ Lang, David Marshall (1980). Armenia, Cradle of Civilization. Allen & Unwin. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-04-956009-3.

- ^ Kurdoghlian, Mihran (1994). Badmoutioun Hayots, Volume I (in Armenian). Hradaragoutioun Azkayin Oussoumnagan Khorhourti. pp. 46–48.

- ^ "History of Armenia in brief". EtnoArmenia Tours (in Italian). Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ Barbara A. West.Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania Infobase Publishing, 1 January 2009; ISBN 1438119135, p. 50

- ^ Redgate, Elizabeth (1998). The Armenians. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 65–68.

- ^ Fuller, J.F.C. (1991). Julius Caesar: Man, Soldier, and Tyrant. Da Capo Press. p. 45. ISBN 0-306-80422-0.

- ^ Armenia Country Study Guide Volume 1 Strategic Information and Developments. International Business Publications, USA. September 2013. ISBN 9781438773827.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Migliorati, Guido (2003). Cassio Dione e l'impero romano da Nerva ad Antonino Pio. Vita e Pensiero. ISBN 9788834310656.

- ^ Vahan Kurkjian: Armenia and the Romans

- ^ DuBois, Michael (16 December 2015). Legio. ISBN 978-1-329-76783-6.

- ^ Authors, Several (17 December 2015). History of The Roman Legions: History of Rome. Self-Publish.

- ^ "The Parthian Period". Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- ^ HA Marcus Antoninus 9.1, Verus 7.1; Dio Cass. 71.3.

- ^ "Armenia: History". Archived from the original on 28 February 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- ^ "Church of Armenia". Archived from the original on 28 January 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- ^ Eastmond, Antony (2003). ""Local" Saints, Art, and Regional Identity in the Orthodox World after the Fourth Crusade". Speculum. 78 (3): 740, Fig.11. doi:10.1017/S0038713400131525. ISSN 0038-7134. JSTOR 20060787.

- ^ "Church of Saint Gregory of Tigran Honents in Ani". Turkish Archaeological News. 10 December 2023.

- ^ Nersessian, Vrej (2001). Treasures from the Ark: 1700 Years of Armenian Christian Art. The British Library Board - Getty Museum. p. 193.

This episode had been represented in the Church of St Gregory at Ani, built by Grigor Honents, in 1215. The king, surrounded by his friends and his army, all on horseback, scts out to greet Gregory

- ^ "Information about Armenia on nationalgeographic.com". Archived from the original on 30 January 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- ^ "Armenian Church History and Doctrine". Archived from the original on 30 July 2009. Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- ^ "The Holy City and the Mother Church of St. Etchmiadzin". Archived from the original on 23 August 2017. Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- ^ "Khor Virap Travel Guide". Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- ^ Anheier, Helmut K.; Juergensmeyer, Mark (9 March 2012). Encyclopedia of Global Studies. SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781412994224. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ Mary Boyce. Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, Psychology Press, 2001; ISBN 0415239028, p. 84

- ^ "Armenian alphabet, pronunciation and language". Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- ^ Johnson, Jerry L. (2000). Crossing Borders--confronting History: Intercultural Adjustment in a Post-Cold War World. University Press of America. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-7618-1536-5.

- ^ "The Sassanids, to 500 CE". Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- ^ "Timeline – Armenia". Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- ^ "Avarayr". Archived from the original on 6 October 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- ^ "Armenians". 8 September 1987. Archived from the original on 11 November 2001. Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- ^ a b Hacikyan, Agop Jack; Basmajian, Gabriel; Franchuk, Edward S.; Ouzounian, Nourhan (2000). The Heritage of Armenian Literature: From the Oral Tradition to the Golden Age. Vol. 1. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-8143-2815-6.

- ^ Dubov, Kalman (26 November 2021). Journey to the Republic of Armenia. Kalman Dubov. pp. 17–18.

- ^ "Armenia - Marzpans, Provinces, Borders | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ Evans, Helen C. (2018). Armenia: Art, Religion, and Trade in the Middle Ages. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-58839-660-0.

- ^ Vasiliev, Alexander A. (1958). History of the Byzantine Empire, 324–1453. University of Wisconsin Press. p. [6]. ISBN 9780299809256.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Redgate, Anne Elizabeth (26 May 2000). Armenians. Wiley. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-631-14372-7.

- ^ "Basil I in Encyclopædia Britannica". Archived from the original on 28 August 2011. Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- ^ "Armenia Sacra" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 January 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2007.

- ^ Clifford Edmund Bosworth, The New Islamic Dynasties, Columbia University (1996), pp. 148–49.

- ^ V. Minorsky, Studies in Caucasian History, Cambridge University Press, 1957. pg 112

- ^ Clifford Edmund Bosworth, The New Islamic Dynasties, pp. 148–149. "..their centres at Tarum and Samiran, and then in Azerbaijan and Arran..", "..into Azerbaijan, Arran, some districts of Eastern Armenia and as far as Darband in the Caspian coast."

- ^ Eastmond, Antony (2017). Tamta's World: The Life and Encounters of a Medieval Noblewoman from the Middle East to Mongolia. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781316711774. ISBN 9781316711774.

- ^ "Alp Arslan". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- ^ "Byzantium and Its Influence on Neighboring Peoples". Retrieved 8 February 2007.

- ^ Mutafian, Claude (1993). Le Royaume Arménien de Cilicie. Paris: CNRS Editions. pp. 13–153. ISBN 2-271-05105-3.

- ^ Edwards, Robert W. (1987). The Fortifications of Armenian Cilicia: Dumbarton Oaks Studies XXIII. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University. pp. 3–282. ISBN 0-88402-163-7.

- ^ Edwards, Robert W., "Settlements and Toponymy in Armenian Cilicia", Revue des Études Arméniennes 24, 1993, pp.181-204.

- ^ a b c "Cilicia: A Historical Overview" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2007. Retrieved 8 February 2007.

- ^ Driscoll, James Francis (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1.

see "IV. THE CRUSADES.........Valiantly they fought with the Christians of Europe, and for their reward, when Antioch had been taken (1097), Constantine, the son of Roupen, received from the crusaders the title of baron..."

- ^ "Dangerous Archaeology". exhibitions.kelsey.lsa.umich.edu. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ Suny, Ronald G. (1 April 1996). Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. DIANE Publishing. pp. 11. ISBN 9780788128134.

- ^ Rayfield, Donald (15 February 2013). Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia. Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781780230702. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ^ Dum-Tragut, Jasmine; Winkler, Dietmar W. (2018). Monastic Life in the Armenian Church: Glorious Past - Ecumenical Reconsideration. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 107. ISBN 978-3-643-91066-0.

- ^ Hewsen, Robert H. (2001). Armenia: a historical atlas. University of Chicago Press. p. 116. ISBN 0-226-33228-4.

- ^ Haxthausen, Baron August von (2016) [1854–55]. Transcaucasia and the Tribes of the Caucasus. Translated by John Edward Taylor. Introduction by Pietro A. Shakarian. Foreword by Dominic Lieven. London: Gomidas Institute. p. 176. ISBN 9781909382312.

- ^ Fisher et al. 1991, p. 332.

- ^ Timothy C. Dowling Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond pp 728–729 ABC-CLIO, 2 December 2014. ISBN 978-1598849486

- ^ a b Mikaberidze, Alexander. Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia 2 volumes: A Historical Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, 22 July 2011; ISBN 978-1598843378, p. 351

- ^ Fisher et al. 1991, pp. 329–330.

- ^ Timothy C. Dowling, Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond, pp 729–30, ABC-CLIO, 2 December 2014; ISBN 978-1598849486.

- ^ Azarian, Haroot (2018). "Armenians in Iran: A Brief History" (PDF). www.odvv.org. Retrieved 22 April 2024., p.29.

- ^ McCarthy, Justin. The Ottoman Peoples and the end of Empire; London, 1981; p. 63

- ^ Arman J. Kirakossian. British Diplomacy and the Armenian Question: From the 1830s to 1914, p. 58

- ^ a b "Hamidian massacres | Armenian Genocide, Ottoman Empire & Sultan Abdul Hamid II | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ Dowling, Timothy C. (2 December 2014). Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond ... Abc-Clio. ISBN 9781598849486. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G (1971). "Russian Armenia. A Century of Tsarist Rule". Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas. 19 (1): 31–48. JSTOR 41044266.

- ^ Bournoutian, George A. (1982). Eastern Armenia in the Last Decades of Persian Rule, 1807–1828. Malibu: Undena Publications. pp. xxii, 165.

- ^ The Cambridge History of Iran by William Bayne Fisher, Peter Avery, Ilya Gershevitch, Gavin Hambly, Charles Melville, Cambridge University Press, 1991, p. 339

- ^ Potier, Tim (2001). Conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia and South Ossetia: A Legal Appraisal. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 2. ISBN 90-411-1477-7.

- ^ Kieser, Hans-Lukas; Schaller, Dominik J. (2002), Der Völkermord an den Armeniern und die Shoah [The Armenian genocide and the Shoah] (in German), Chronos, p. 114, ISBN 3-0340-0561-X

Walker, Christopher J. (1980), Armenia: The Survival of A Nation, London: Croom Helm, pp. 200–03

Bryce, Viscount James; Toynbee, Arnold (2000), Sarafian, Ara (ed.), The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, 1915–1916: Documents Presented to Viscount Grey of Falloden (uncensored ed.), Princeton, NJ: Gomidas, pp. 635–649, ISBN 0-9535191-5-5 - ^ For example: