Aua, American Samoa

A major contributor to this article appears to have a close connection with its subject. (February 2024) |

ʻAūa | |

|---|---|

Village | |

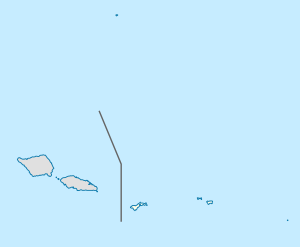

| Coordinates: 14°16′11″S 170°39′50″W / 14.26972°S 170.66389°W | |

| Country | |

| Territory | |

| Island | Tutuila Island |

| Area | |

• Total | 1.11 sq mi (2.88 km2) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 1,549 |

| • Density | 1,400/sq mi (540/km2) |

| Demonym | Auan[1] |

| Time zone | Samoa Time Zone |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−11 |

| ZIP code | 96799 |

| Area code | +1 684 |

Aūa is a village on Tutuila Island in American Samoa. It is located along American Samoa Highway 001, and is the southern terminus of American Samoa Highway 006. Aūa is located at the foothills of Mount Peiva on the eastern shore of Pago Pago Bay.[2][3] The hamlet of Leloaloa is also a part of Aūa.[4]

Corals off the village of Aūa have been the subject of what's thought to be the world's longest-running reef survey. It has attracted scientists from throughout the world every year since 1917.[5] In 1917 Alfred G. Mayer from the Carnegie Institution for Science established what has now become the oldest periodically re-surveyed coral-reef transect in the world at Aua.[6]

Sa’ousoalii is a traditional salutation to the villages of Aua and Fagatogo in the Greater Pago Pago Area.[7]

Historical records reveal that, prior to 1900, extensive areas along the Pago Pago Harbor coastline, including the present-day locations of Aua Village and Utulei Village, were covered by mangrove vegetation.[8]

History

[edit]On January 10, 1878, during the Tutuila War, Puletua rebels fled from Aua to Aunu’u Island after being pursued by government forces.[9]

In July 1892, unrest in Maʻopūtasi County had significant consequences for Aua. Mauga Lei, who had aligned himself with Malietoa Laupepa during their shared exile in the Samoan Civil War, spent much of his time in Upolu after returning to Sāmoa. This absence left Aua and nearby areas without direct leadership. While Pago Pago remained loyal to Mauga Lei, Aua, along with Fagatogo, sought to replace him with a new titleholder. Villagers from Aua and Fagatogo joined forces and set out in boats toward Pago Pago to challenge Mauga Lei's position. However, as they neared Pago Pago, they were met with a heavy barrage of gunfire, forcing them to retreat. In retaliation, their opponents carried out incendiary raids on Aua, devastating the village with fire. The women and children of Aua fled to safety at the Roman Catholic Mission in Lepua, while the men escaped by sea to take refuge on Aunuʻu Island.[10]

In 1893, acting consul William Blacklock traveled to Tutuila to explore the possibility of acquiring land. Both Blacklock and Harold M. Sewall were concerned about potential British efforts to purchase a plot in Aua. However, it appears the British were primarily seeking a location for a relay station to support their planned cable linking British Columbia and Australia. Ultimately, they shifted their focus to a more suitable site at Fanning Island.[11]

In 2021, the Voice of Christ Lighthouse Temple was dedicated at Aua.[12] The church also operates a Bible school, the Lighthouse Bible School, in Aua.[13]

World War II

[edit]During World War II, Aua became the site of several military installations. A central tank farm featured eleven large cylindrical tanks for diesel storage, complemented by scattered pump houses that maintained these tanks. On the western side of this farm, a construction battalion camp was established, consisting of around twelve buildings and a mess hall. Between Aua Village and Breakers Point, three separate U.S. Marine camps were set up. The first, the Samoa Marine camp, included sixteen structures along both sides of the road, such as living quarters, storage buildings, three mess halls, a sick bay, a guardhouse, and a refrigeration shed. The second, centrally located camp, comprised twenty-six buildings, including living quarters, mess halls, storage areas, a movie theater shed, and a post exchange. The southernmost camp housed twenty-one structures, which featured lookout, searchlight, and signal towers in addition to standard living quarters, storage facilities, and mess halls. Construction of the Aua fuel farm was completed on December 31, 1943. The U.S. Navy took over operations, using the farm for bulk fuel oil storage and distribution, as well as maintaining a construction battalion camp to support Naval Station Tutuila during the war. The entire project occupied approximately 44 acres in Aua Village, stretching from Highway 1 to the foothills of the axial mountain range. By May 1947, historical records indicate that the tanks were removed from the inventory of the U.S. Naval Station.[14][15]

After the conclusion of World War II, the tank farm was dismantled and demolished, leading to the leakage of diesel fuel from several storage tanks. Over time, villagers constructed residences on the remnants of the tank farm. Residents later identified the presence of underground petroleum contamination at multiple locations throughout the village.[16][17]

Geography

[edit]

Aua, which is situated at the base of Rainmaker Mountain, serves as the starting point for a winding road featuring numerous switchbacks. This road ascends through Rainmaker Pass, offering expansive views of the surrounding landscape, and connects to the north shore village of Vatia.[19]

The Aua area contains five rivers or streams: Amano, Lalomauta, Suaia, Matagimalie, and Leasi Streams.[20]: 24:5–6 A 9-acre wetland area is situated near the center of the village. The smaller mangrove swamp stretches inland from the shoreline roadway to a site southwest of the LDS complex and the elementary school. The swamp is fed from the Lalolamauta Stream as well as runoff from Matagimalie and Suaia Streams.[20]: 24:12–13

Toasa Rock outside Aua is about 20 yards in diameter and covers 2 feet.[21]

Onesosopo Park

[edit]On May 25, 1984, a groundbreaking ceremony was held at the Onesosopo reclamation site in order to initiate work on the first park in Tutuila's Eastern District. Onesosopo Park is located at Onesosopo, which is between Lauliʻifou (Tafananai) and Aua. It was completed and dedicated in 1990. The park houses swimming, picnic and restroom facilities.[22] Fagaʻitua Vikings, the high school football team at Fagaʻitua High School, practices at the uneven turf at Onesosopo Park.[23] It is a public park which is operated by American Samoa Department of Parks and Recreation.[24] The high school's baseball team also trains here as well as Aua's rugby team, the Aua Black's and also Lauliʻi’s rugby team, Moli ole Ava.[25]

The lack of skilled workers such as engineers, plumbers, electricians, and woodworkers have led to problems with improvement work at various Tutuila parks. Renovation and redevelopment work at Onesosopo Park, however, has received funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which had raised $201,000 for the park as of 2016.[26] Onesosopo Park received new urinals and toilets during a 2018 renovation. The work was funded by a $75,000 grant from the Land and Water Conservation Fund. The park is utilized for camping, picnicking, reunions and other gatherings throughout the year.[27]

In 2017, the summer baseball clinics, hosted by the American Samoa Softball Association (ASSA) in collaboration with the Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR), were held at Onesoso Park and in the Tafuna area.[28] Eastern Star Youth Football League games have also been held at the park.[29]

Legend

[edit]The village of Aūa in American Samoa is well known for its ceremonial field or malae, named Malaeopaepaeulupoo ("Field of stacked skulls"). Between the late 13th century to early 14th century, the cannibal chief Tuifeai, also known as Tuisamoa, the son of Tuifiti, lived in Malaeloa, which is adjacent to the village and ancient capital of American Samoa. (Tuisamoa is the title Malietoa gave him after he was born, from the union of the Tuifiti with Malietoa's sister). The Tuifeai required sacrifices of humans as his meal everyday, this tradition is called aso, or "the king's day".

Upon receiving his daily meal Tuifeai would take the skulls with him to the village of Aua, his refuge and stronghold from his enemies. Thus he ruled Tutuila as one of the reigning Paramount Chiefs. While Malietoa, Tuiaana and Tuiatua reigned in Upolu and Savaii, and Tuimanuʻa in Manuʻa, Tuifeai ruled in Tutuila. While in Aua Tuifeai would dress his ceremonial grounds in front of his "great house" with the skulls from his aso, as a boundary or border, intimidating anyone who dared defy him. The skulls acted as a wall or stacked border, signifying a sa ("sacred grounds"), indicating where no one was to approach.

Lutu and Solosolo of Sapunaoa, in the District of Atua (and sub-district of Falealili) sailed to Tutuila. Upon arriving in Leone, they trekked towards Taputimu through Vailoa. In Vailoa they found some of Tuifeai's warriors and battle raged. After slaying almost all of Tuifeai's troops, some having run off, they left one alive to report back to Tuifeai that they were here to have him taoiseumu ("cooked in an umu"). They then proceeded to Leala, in Taputimu, and chopped down the tautu tree where Tuifeai had his leftover victims hung. The salty seabreeze and sun made jerky out of his leftover humans.

Tuifeai fled up the mountains through Aasu (Aloau was down on the north shore then), and headed towards Aua. When Lutu and Solosolo were told, they sailed from Leone towards Aua. Upon entering the Malaeopaepaeulupoo, they prepared an umu, with anticipation of Tuifeai being cooked in it when he shows up. Instead of using a sasaʻe and ieofi for spreading and handling the hot rocks of the umu, they used their feet and bare hands. Tuifeai was a descendant of the Tuifiti (Fijian), who were well known as "fire walkers", walking barefoot on hot rocks during their ancient ritual dances, showing their bravery. Lutu and Solosolo were showing Tuifeai that they too were not afraid of fire. Word quickly spread of the umu a toa (umu of warriors).

Tuifeai never came back down from the mountain village route. Thus that district became known as Aitulagi ("ghost in the sky"). The two warriors patrolled the Fagaloa in their war outrigger soatau in case Tuifeai decided to return. After a while, they decided that Lutu would stay in Fagatogo, whom the Fagatogans requested, in order to guard them against Tuifeai, and for Solosolo to stay in Aua. They ripped the sail on their outrigger in two to seal their covenant. The sealing of the covenant became known as le launiu na saelua (the coconut frond ripped in two), and it historically changed the course of Samoan history – the warriors will not be sailing back home to Lufilufi (their sail being purposely ripped in two) and cannibalism will forever be abolished in Tutuila, their presence remaining.

Solosolo was bestowed the Paramount Chief title of Unutoa (unu being to reform or extract the human element out of the "aso", toa being "warrior, hero"), the "reformation warrior". Lutu retained the name Lutu in Fagatogo. Solosolo's kava-cup name in Lufilufi, whenever he decides to visit, is Moetoto ("slept bloody").[30]

To this day a skull may be found when digging for a grave or a foundation for a house around the village of Aua. The name Paepaeulupoo is also the name of the village fautasi (longboat). Paepaeoulupoʻo and Paepaeala are the names of the village malae.

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Population[31] |

|---|---|

| 2020 | 1,549 |

| 2010 | 2,077 |

| 2000 | 2,193 |

| 1990 | 1,896 |

| 1980 | 1,379 |

References

[edit]- ^ Gray, John Alexander Clinton (1980). Amerika Samoa. Arno Press. Page 95. ISBN 9780405130380.

- ^ Krämer, Augustin (2000). The Samoa Islands. University of Hawaii Press. Page 438. ISBN 978-0-8248-2219-4.

- ^ Sunia, Fofō Iosefa Fiti (2001). Puputoa: Host of Heroes - A record of the history makers in the First Century of American Samoa, 1900-2000. Suva, Fiji: Oceania Printers. Page 190. ISBN 978-982-9036-02-5.

- ^ Krämer, Augustin (2000). The Samoa Islands. University of Hawaii Press. Page 438. ISBN 9780824822194.

- ^ "American Samoan reef surveyed over 100 years". 22 May 2017.

- ^ "American Samoans urged to protect AUA coral". 26 May 2017.

- ^ Sunia, Fofō Iosefa Fiti (2001). Puputoa: Host of Heroes - A record of the history makers in the First Century of American Samoa, 1900-2000. Suva, Fiji: Oceania Printers. Page 193. ISBN 978-982-9036-02-5.

- ^ South Pacific Regional Environment Programme (1999). Coastal Management Profiles: A Directory of Pacific Island Governments and Non Government Agencies with Coastal Management Related Responsibilities. SPREP's Climate Change and Integrated Coastal Management Programme. Page 23. ISBN 978-982-04-0198-3.

- ^ Pearl, Frederic and Sandy Loiseau-Vonruff (2007). “Father Julien Vidal and the Social Transformation of a Small Polynesian Village (1787–1930): Historical Archaeology at Massacre Bay, American Samoa”. International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 11(1): p. 38. ISSN 1092-7697.

- ^ Gray, John Alexander Clinton (1960). Amerika Samoa: A History of American Samoa and its United States Naval Administration. United States Naval Institute. Pages 95-96. ISBN 978-0-87021-074-7.

- ^ Gray, John Alexander Clinton (1960). Amerika Samoa: A History of American Samoa and its United States Naval Administration. United States Naval Institute. Page 106. ISBN 978-0-87021-074-7.

- ^ Aitaoto, Fuimaono Fini (2024). Science-Christianity and Church Activities in the Samoan Islands: Early 21st Century: An Update. LifeRich Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4897-5022-8.

- ^ Aitaoto, Fuimaono Fini (2021). Progress and Developments of the Churches in the Samoan Islands: Early 21St Century. LifeRich Publishing. Pages 198-199. ISBN 978-1-4897-3586-7.

- ^ https://www.poh.usace.army.mil/Missions/Environmental/FUDS/Aua-Fuel-Farm/

- ^ https://npshistory.com/publications/npsa/brochures/naval-ww2-history.pdf

- ^ Sagapolutele, Fili (2016). “Aua petroleum contamination needs no further action, says Army Corps”. Samoa News. Retrieved on December 29, 2024, from https://www.samoanews.com/local-news/aua-petroleum-contamination-needs-no-further-action-says-army-corps

- ^ Wise, D.L. (1997). Global Environmental Biotechnology. Elsevier Science. Page 400. ISBN 978-0-08-053255-4.

- ^ Goodwin, Bill (2006). Frommer's South Pacific. Wiley. Page 401. ISBN 978-0-471-76980-4.

- ^ https://www.frommers.com/destinations/american-samoa/attractions/overview

- ^ a b "AMERICAN SAMOA WATERSHED PROTECTION PLAN: Volume 2: Watersheds 24-35" (PDF). American Samoa Environmental Protection Agency. 2000. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ U.S. Defense Mapping Agency (1977). "Sailing Directions for the Pacific Islands: Volume 3, the South-central Groups". U.S. Department of Defense. Page 166.

- ^ Sunia, Fofo I.F. (2009). A History of American Samoa. Amerika Samoa Humanities Council. Page 332. ISBN 9781573062992.

- ^ Ruck, Rob (2018). Tropic of Football: The Long and Perilous Journey of Samoans to the NFL. The New Press. ISBN 9781620973387.

- ^ "Park usage numbers increase despite major problems with vandalism and limited facilities". 25 February 2013.

- ^ "TMO Marist 7s Flag Day Tourney ready, set to go". 28 March 2014.

- ^ "Tuai ona faʻaleleia Paka i Fagaalu ma Utulei" (in Samoan). Samoa News. 9 September 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ "Freedom Run and Obstacle Course back for third year". 11 June 2018.

- ^ "Solaita Baseball Field conditions". 24 July 2017.

- ^ "ESYFL closes its regular season this Saturday". 26 April 2012.

- ^ All dates and names are found in Dr. A Kramer's "The Samoan Island" as well as many other Samoan historical documents and archeological findings.

- ^ "American Samoa Statistical Yearbook 2016" (PDF). American Samoa Department of Commerce. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-02-14. Retrieved 2019-07-25.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch