Battle of Port Lyautey

| Battle of Port Lyautey | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Operation Torch of World War II | |||||||

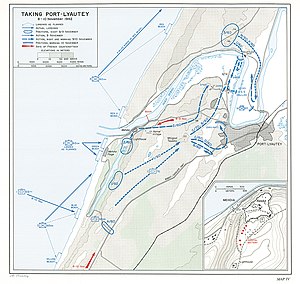

Map of the American landing at Port Lyautey, French defensive and counter-attack positions in red | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| | | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| | | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 79 killed[1] | Heavy; over 400 casualties | ||||||

The Battle of Port Lyautey began on 8 November 1942 for the city of Port Lyautey, today known as Kenitra, in French Morocco. The battle ended with its capture and occupation by American troops, overrunning French forces after more than two days of fierce fighting.

Objectives

[edit]The attack was a part of the objectives of the Western task force as part of Operation Torch,[2] a large Allied landing to seize control of North Africa from German control. Within the task force, Sub Task Force Goalpost was tasked with the objective of securing Port Lyautey. There were three objectives to the attack:

- Capture the beach village of Mehdiya

- Capture the fortress which secured the river mouth (the Kasbah Mahdiyya 34°15′51″N 006°39′27″W / 34.26417°N 6.65750°W)

- Secure the airfield

Command structure

[edit]The operation was under the command of U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, and the western task force was under the command of General George S. Patton. Sub Task Force Goalpost was under the command of General Lucian Truscott.[3]

Prelude

[edit]Planning

[edit]Prior to the landings in French Morocco, and after the fall of France in World War II, the U.S. State Department had maintained in French North Africa an unusually large number of very able consular officials. This group was under the leadership of Mr. Robert Murphey, later General Eisenhower's political adviser. From these sources and from the military attache in Tangiers, the U.S. Army obtained much detailed information concerning conditions in Morocco and were placed in contact with loyal Frenchmen who opposed the Vichy regime and were not friendly toward Axis forces.[4]

One Englishman and one Frenchman were smuggled into London, Karl Victor Clopet and René Malevergne.[4] Clopet had an intimate knowledge of the ports, beaches and coast defenses along the entire coast as a result of living in Casablanca for over 12 years and with tight connections to salvage operations there.[4] Malevergne was familiar with every turn and bar in the Sebou river channel, knew all of the shipping which was engaged in the coastal trade, and provided important information concerning pro-Nazi political sentiment which was stronger in the Port Lyautey area than in any other section of Morocco.[4]

Preparation for battle

[edit]Outline plans were drawn up in London for the assault on Port Lyautey by Gen. Truscott and his staff. Capturing and stocking the airfield at Port Lyautey was the primary mission. Infantry and armored combat teams were at Fort Bragg in North Carolina. This would primarily be the 9th Infantry Division, 60th Infantry Regiment "Go Devils".[4]

Personnel and Vehicles Assigned to Force "Z" (Goalpost), as of 22 October 1942:[5]

| Unit | Personnel | Vehicles |

|---|---|---|

| 9th ID 1st BLT, 60th Infantry | 1345 | 118 |

| 9th ID 2nd BLT, 60th Infantry | 1268 | 117 |

| 9th ID 3rd BLT, 60th Infantry | 1461 | 118 |

| Other 60th Infantry Troops | 1318 | 224 |

| 66th Armored Landing Team, 1st Battalion, 66th Armored Regiment | 919 | 163 |

| XII Air Support Command | 1936 | 103 |

| 692nd-697th Coast Artillery (AA) Batteries | 448 | 0 |

| 66th Topographic Engineer Company (Detachment) | 5 | 0 |

| 1st Armored Signal Battalion | 3 | 1 |

| 9th Signal Company | 68 | 10 |

| 122nd Signal Company | 26 | 4 |

| 163rd Signal Company | 6 | 1 |

| 239th Signal Company | 35 | 4 |

| 56th Medical Battalion | 36 | 0 |

| 2nd Broadcasting Station Operation Detachment | 30 | 5 |

| Counterintelligence Group | 16 | 0 |

| Prisoner Interrogation Group | 21 | 0 |

| Civil Government Personnel | 4 | 0 |

| Force Headquarters | 46 | 10 |

| Submarine Markers | 30 | 0 |

| Harbor Obstruction Experts | 40 | 0 |

| Naval Personnel | 18 | 0 |

| Total | 9079 | 881 |

Logistics and embarkation

[edit]It was realized early on that there were not sufficient berths in the port of embarkation to permit all of the Western Task Force to load and embark simultaneously. One Sub Task Force would have to load early, a full week before setting sail. The 60th Regiment and the 1st Battalion Combat Team of the 66th Armored Regiment were well organized and all were as well trained as could have been expected, to include some amphibious training. A commanders conference was held on 14 October in Washington, D.C., with Gen. Patton. It was noted that a counter sign for the attack had not been developed yet for identification purposes during operations. Someone suggested the words "George Patton" which met with unanimous approval. The challenger would call "George"; the challenged, if a friend, would answer "Patton". On the night of 15 October, troops and equipment were embarked. Some last minute loading was done on 16 October, and at 13:40 on that day, the sub task force sailed for Solomon's Island in Chesapeake Bay, where they had their rehearsal training.[4]

On the beaches at Solomon's Island, tests of naval gunfire or air support were not allowable, but tests of communications and procedures would be the primary focus. On 17 October, all rehearsal training seemed to be going according to plan. Transports were riding at anchor with landing craft swarming in the water about them. However, at some point, Colonel Demas T. Craw reported from one of the ships that the ship's captain had refused to hang any nets or lower any craft, giving the reason that his crew was not sufficiently trained to go on the expedition.[4] After Gen. Truscott visited with the ship's captain for a while, and informing him that the inadequate state of training and preparation was known, his refusal would have no effect on the overall operation. The captain relented, and training on that ship began. The next day, their voyage to North Africa began.

Lyautey airfield support

[edit]The Port Lyautey area, lying in a "U" bend of the Sebou River, contained an airfield with concrete runways and hangars on the low flats next to the river and approximately five miles from the landing beaches but nine miles up the shallow river with a maximum depth that even at the highest November tides limited access to ships drawing no more than 19 feet (5.8 m).[6] Early planning had envisioned aircraft from Gibraltar landing at the field after capture; later plans called for the aircraft to be launched from the auxiliary aircraft carrier USS Chenango.[7]

Military planners addressed the question of supplying aviation gasoline and munitions directly to airfield by means of the Sebou River to docks at the airfield.[8] The search for a shallow draft ship settled on the Honduran registered SS Contessa, a Standard Fruit & Steamship Company refrigerated cargo and passenger vessel, built in 1930, that had operated between Caribbean ports and the United States.[8][9][10] The War Shipping Administration was empowered to take over all oceanic shipping. It took over Contessa for war service on 29 May 1942 with Standard Fruit as its operating agent. Contessa was chartered at the last minute for the operation.[10][11]

According to a popular magazine article written a year later, a message was sent to the ship's commander—Capt. William H. John—to go to Newport News to undertake a secret war mission.[12] The ship's steward was a colorful man who spent his off hours trying to save the souls of the crew and the other half praying for the Contessa's welfare.[12] The boat was nearing the end of her rope, she was salt cracked, rust stained, and her degaussing equipment was gone.[12]

Contessa arrived at Norfolk as the convoy was preparing to sail. She was in a leaking condition with engine problems that required immediate dry docking that was expected to take several days.[13] By extraordinary effort the ship was repaired early, but in the meantime much of the crew had left town in expectation of a longer stay.[13] Three days late, with a crew filled out from seaman volunteers from a local Naval brig released from minor offenses, the ship got underway in the early hours of 27 October in an unescorted dash across the Atlantic to join the convoy.[11][14][15] Contessa, loaded with only 738 tons of gasoline and bombs, overtook the convoy on 7 November.[16][17][note 1]

Battle

[edit]7 November

[edit]The Northern Attack Group, Sub Task Force Goalpost, arrived off Mehdia, Morocco, just before midnight, 7–8 November 1942.

The battleship Texas and light cruiser Savannah took up station to the north and south of the landing beaches. The transport ships had lost formation in the last part of the approach to Morocco, and had not regained it. Some landing craft from five of the ships were first to carry troops from the other three, much confused searching causing a delay in forming waves for the actual landings. Gen. Truscott was ferried from transport to transport and agreed to postpone H-Hour from 04:00 to 04:30.

The messages of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Gen. Eisenhower were already broadcast from London much earlier, and in the Mediterranean, the landings were well advanced before those at Mehdia commenced. Surprise was lost.[18]

Defenses at Mehdia were lightly manned. Naval crews operated two 5 in (130 mm) guns in protected positions on the tableland above Mehdia village and in the vicinity of the Kasbah. Not more than 70 men occupied the fort when the attack started. Two 75 mm (2.95 in) guns were mounted on flat cars on the railroad running beside the river at the base of the bluff on which the Kasbah lay. A second battery of four 75 mm guns was brought forward after the attack began to a position on the high ground along the road from Mehdia to Port Lyautey. A battery of four 155 mm (6.1 in) guns (Grandes Pussances Filloux) was emplaced on a hill west of Port Lyautey and south west of the airport. The airport was defended by a single anti-aircraft battery. The infantry consisted of the 1st Regiment of Moroccan Infantry and the 8th Tabor (battalion) of native Goums. One group of nine 25 mm (0.98 in) guns had withdrawn from other infantry regiments and one battalion of engineers completed the defensive force. Reinforcements were sent to occupy the entrenchments and machine gun positions which covered approaches to the coastal guns and the fort and to occupy defensive positions on the ridges east of the lagoon.[18]

8 November

[edit]At first light on the 8th, Col. Demas T. Craw and Maj. Pierpont M. Hamilton went by jeep from an early beach landing, to Port Lyautey to consult the French commander (Col. Charles Petit). The emissaries were to give him a diplomatic letter in the hopes of preventing any hostilities from starting. They went ashore as the fire of coastal batteries and warships and strafing French airplanes began. French troops near the Kasbah directed them toward Port Lyautey, but as they neared the town under a flag of truce, a French machine gunner at a road fork outpost, stopped them with a burst of point-blank fire which killed Col. Craw. Major Hamilton was then conducted to the headquarters of Col. Petit, where his reception led to no conclusive reply.[18] The pervading atmosphere at the French headquarters in Port Lyautey was one of sympathy toward the Allied cause and distaste for the current fighting. What was lacking was an authorization from Col. Petit's superior to stop fighting. Pending receipt of such authorization, the French at Port Lyautey continued to fight[18] Units of the 60th Infantry Regiment began disembarking troops and supplies from their ships just off the Moroccan shore.[19] The first wave of landing boats began circling and grouping together in preparation for the coming invasion. Unfortunately, in the confusion of disembarkation, the first wave was delayed as they looked for guidance to the shoreline; hence the second wave pressed into the shore as planned, on time. As the second wave began their attack, the first wave started in toward their objectives. Confusion was prevalent in the landing operation. Once the first wave made it to shore, the French defenders began resisting with small arms fire as well as cannon fire from a fortress (Kasbah 34°15′51″N 006°39′27″W / 34.26417°N 6.65750°W) overlooking the area.[20] For all of the first day, the 60th Regiment achieved their first objective of securing the beach, but had not secured their other objectives. The night of the 8th was stormy, men were trying to rest anywhere, and many scurried through the blackness to find their units.[2]

9 November

[edit]On the second day, further attacks began against the Kasbah fortress.[2] The ground around the fortress was taken and secured, but the fort itself was still successfully defending itself. At the end of the day, a number of attacks were repulsed by the French defenders, the American attackers had not met with success.

10 November

[edit]Finally, on the third day, 10 November, the fortress was overrun and captured, leading to the final success of capturing the local airfield.[2] At 1620 the Contessa entered the Sebou River to deliver the aviation gasoline and munitions for the seventy-six Army P-40 aircraft launched in the morning by Chenango but ran aground when passing the Kasba and had to await a higher tide the morning of 11 November.[17]

These victories led to a truce being established on 11 November.[2]

Aftermath

[edit]- Muslim graves of the French Military Cemetery of Kenitra, where are buried some of the soldiers who fought the US landing.

- Laying wreath at American cemetery, near Kasbah Mehdia, Port Lyautey, Morocco, 1943 (27657266311)

After the battle, most units involved remained in the area. In January, President Roosevelt visited the area, as a surprise to the troops. He toured the Kasba, and saw the area where the troops had come ashore. In a small cemetery of American dead, he placed a wreath to commemorate their sacrifice. Col. Fredrick de Rohan gave the president an overview briefing of the battle itself.

In the tent city erected near the kasba, Pvt. Karl C. Warner of New York had been elected governor of tent city.

After the battle, Gen. George Patton proclaimed the Battle of Port Lyautey as very serious.[21] Beach conditions were bad, many boats were lost in the landing, and it took more than two days to capture the fort.[21] The French put up a gallant fight.[21]

After the battle, a cemetery was created in the immediate vicinity of the kasbah fortress. Here, the men who died in the battle of Port Lyautey were interred. In January 1943 General Mark Clark laid a wreath at the flagpole in the cemetery.

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Contessa, later under bareboat charter by the Army for service in the Southwest Pacific Area, normally had a draft of 30 feet 6 inches (9.3 m), according to the 1942—43 Lloyd's Register. It is possible the light load was intended to lighten the ship in order to pass the Sebou River entrance bar.

See also

[edit]- Kenitra (Port Lyautey, Morocco)

- List of equipment of the United States Army during World War II

- List of French military equipment of World War II

- Operation Torch

- North Africa Campaign

- Dwight D. Eisenhower

- George Patton

- Lucian Truscott

- US Naval Bases North Africa

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Chapter VIII Mehdia to Port-Lyautey". HyperWar: US Army In WWII. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Mittleman, Joseph (1948). Eight Stars to Victory. F.J. Heer Printing Company.

- ^ Howe 1993, p. 42.

- ^ a b c d e f g Truscott Jr., L.K. (1954). Command Missions, A Personal Story. E.P. Dutton.

- ^ Howe 1993, p. 151.

- ^ Howe 1993, p. 147.

- ^ Howe 1993, pp. 44, 147, 150, 167–168.

- ^ a b Howe 1993, p. 44.

- ^ Leighton & Coakley 1955–68, p. 444, v.1.

- ^ a b Maritime Administration.

- ^ a b Bykofsky & Larson 1990, p. 148.

- ^ a b c Fowler, Bertram B. (August 28, 1943). "12 Desperate Miles, A Wartime Saga of the S.S. Contessa". The Saturday Evening Post.

- ^ a b Howe 1993, p. 68.

- ^ Bykofsky & Larson 1990, p. 148, fn #32.

- ^ Leighton & Coakley 1955–68, pp. 444–445, v.1.

- ^ Leighton & Coakley 1955–68, p. 445, v.1.

- ^ a b Howe 1993, pp. 150, 169.

- ^ a b c d *Morison, Samuel Eliot. (1947). "Operations in North African Waters, October 1942-June 1943", Castle Books.

- ^ *Eisenhower, John S.D. (1982). "Allies", Da Capo Press

- ^ Jones, V (1972). Operation Torch Anglo-American Invasion of North Africa. Ballantine.

- ^ a b c Cunningham, C.R. (November 18, 1942). "Surprise Won In Morocco Attack". Oakland Tribune.

References

[edit]- Bykofsky, Joseph; Larson, Harold (1990). The Technical Services—The Transportation Corps: Operations Overseas. United States Army In World War II. Washington, DC: Center Of Military History, United States Army. LCCN 56060000.

- Fowler, Bertram B. (1943). "12 Desperate Miles, A Wartime Saga of the S.S. Contessa", The Saturday Evening Post August 28, 1943.

- Eisenhower, John S.D. (1982). "Allies", Da Capo Press.

- Howe, George F. (1993). The Mediterranean Theater of Operations — Northwest Africa: Seizing The Initiative In The West. United States Army In World War II. Washington, DC: Center Of Military History, United States Army. LCCN 57060021.

- Jones, V (1972). "Operation Torch Anglo-American Invasion of North Africa", Ballantine Books.

- Leighton, Richard M; Coakley, Robert W (1955–68). The War Department — Global Logistics And Strategy 1940–1943. United States Army In World War II. Vol. 1. Washington, DC: Center Of Military History, United States Army. LCCN 55060001.

- Maritime Administration. "Contessa". Ship History Database Vessel Status Card. U.S. Department of Transportation, Maritime Administration. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- Mittleman, Joseph. (1948). "Eight Stars to Victory", F.J. Heer Printing Company.

- Moran, Charles. (1944). "The Landings in North Africa", US Government Printing Office.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot. (19470. "Operations in North African Waters, October 1942-June 1943", Castle Books.

- Truscott, L.K. Jr. (1954). "Command Missions, A Personal Story", E.P. Dutton and Company, Inc.

- Cunningham, C.R. (1942). "Surprise Won in Morocco Attack", Oakland Tribune, Nov 18, 1942.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch