Battle of White Bird Canyon

| Battle of White Bird Canyon | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Nez Perce War | |||||||

White Bird Battleground panorama, Idaho, 2003 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| | Nez Perce | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Capt. David Perry Capt. Joel Graham Trimble | Chief Joseph Ollokot White Bird | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 106 soldiers; 11 civilian volunteers, 13 Nez Perce scouts | about 70 warriors | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 34 killed 4 wounded | 3 wounded | ||||||

Location in the United States Location in Idaho Territory | |||||||

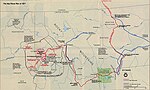

The Battle of White Bird Canyon was fought on June 17, 1877, in Idaho Territory. White Bird Canyon was the opening battle of the Nez Perce War between the Nez Perce Indians and the United States. The battle was a significant defeat of the U.S. Army. It took place in the western part of present-day Idaho County, southwest of the city of Grangeville.

Prelude to war

[edit]The original treaty between the U.S. government and the Nez Perce, signed in 1855, established a reservation that acknowledged the ancestral homelands of the Nez Perce. In 1860, the discovery of gold on the Nez Perce Indian Reservation (near Pierce) brought an uncontrolled influx of miners and settlers into the area. Despite numerous treaty violations, the Nez Perce remained peaceful.

Responding to pressures to make land available to settlers, the U.S. government forced another treaty on the Nez Perce in 1863, reducing the size of the reservation by 90%.[1][2] The leaders of the bands living outside the new reservation refused to sign the "steal treaty" and continued to live outside the new reservation boundaries for another fourteen years, until the spring of 1877.

In May 1877, after several attacks from the U.S. Army, the non-treaty bands moved from their homelands towards the new reservation. The Wal-lam-wat-kain (Wallowa) Band, led by Chief Joseph, lost a large number of horses and cattle crossing rivers swollen with spring runoff. Joseph's and Chief White Bird's bands eventually gathered at Tepahlewam, the traditional camping ground on the Camas Prairie at Tolo Lake to enjoy the last days of their traditional lifestyle. It was an emotional rendezvous; not all the people agreed with the course of peace and compliance.

On June 14, seventeen young men, including Wahlitits, entered the Salmon River area to seek revenge for the 1875 murder of Wahlitits' father, Tipyahlanah Siskan and others killed in the attacks. The proclaimed success of their mission roused the desire for vengeance among other warriors and resulted in more attacks on settlers in the area on June 15. At least 18 settlers were killed by the Nez Perce. Settlers sent messengers from the community of Mount Idaho to Fort Lapwai describing these events and demanding assistance from the military.

The Nez Perce at Tepahlewam were aware that Brigadier General O. O. Howard was preparing to send his soldiers against them. By June 16, the bands had moved to the southern end of White Bird Canyon, about five miles (8 km) long, one mile (1.6 km) wide at its maximum, and bounded by steep mountain ridges. That night, sentinels reported the approach of U.S. soldiers from the north. After much deliberation, the Nez Perce decided that they would stay at White Bird and make an effort to avoid war, but fight if they were forced to do so.

The combatants

[edit]Captain David Perry commanded Company F and Captain Joel Graham Trimble commanded Company H of the 1st Cavalry Regiment. The officers and men of the two companies totaled 106. Eleven civilian volunteers rode with the soldiers and 13 Nez Perce scouts from treaty bands had been recruited at Fort Lapwai. Nearly half the soldiers were foreign-born and most were inexperienced and inexpert horsemen and marksmen. Their horses, as well as the riders, were untrained for battle and both men and horses arrived exhausted at White Bird Canyon after a two-day ride of more than 70 miles.[3]

The Nez Perce counted as many as 135 warriors, but they had stolen a large quantity of whiskey in their raids and, on the morning of June 17, many of the men were too drunk to fight. Only about 70 men participated in the battle. Ollokot and White Bird led roughly equal numbers of warriors. Chief Joseph may have fought in the battle, but he was not a war leader.

The Nez Perce had only 45–50 firearms, including shotguns, pistols, and ancient muskets. Some warriors fought with bows and arrows. Although the Nez Perce had no experience of war with White soldiers, their knowledge of the terrain and their superb horsemanship and well-trained Appaloosa horses were advantages. Accustomed to economy in the use of bullets in hunting, the Nez Perce were also good marksmen. They usually dismounted from their horses to fire and a fighter's horse would "stand and eat grass while his owner fought." By contrast, many U.S. Cavalry horses panicked in the battle and that panic was given as a major reason for the U.S. defeat.[4]

Truce party

[edit]

At daybreak on June 17, the Nez Perce were preparing for the expected attack. Awaiting the soldiers, 50 warriors under Ollokot deployed to a butte on the western side of the canyon and 15 warriors under Two Moons on a butte to the east, thus placing themselves on both sides of the cavalry's route down the canyon.[5] Six Nez Perce warriors waited with a white flag to discuss a truce with the approaching soldiers.

The soldiers, civilian volunteers, and Nez Perce scouts descended into White Bird Canyon along a wagon road from the north east.[6] An advance party, consisting of Lieutenant Edward Theller, Trumpeter John Jones, a few Nez Perce scouts employed by the Lapwai Agency, seven soldiers from Company F and civilian volunteer Arthur "Ad" Chapman made first contact with the truce party. Yellow Wolf later gave this account:

- Five warriors, led by Wettiwetti Houlis...had been sent out from the other [west] side of the valley as a peace party to meet the soldiers. These warriors had instructions from the chiefs not to fire unless fired upon. Of course they carried a white flag. Peace might be made without fighting.[7]

For reasons never fully explained, Chapman fired at the truce party. The truce party took cover and the Nez Perce returned fire.[8]

The Battle

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2014) |

Following the opening shots, Lieutenant Theller, in his advanced position, dismounted and deployed his men as skirmishers on top of a low ridge. Trumpeter Jones was ordered to signal a call to arms to bring all troops forward to join him. Before Jones could finish his trumpet call, he was shot from his horse by Otstotpoo, positioned more than 300 yards (270 m) away on a knoll to the east. Captain Perry dismounted his company and formed a skirmish line on the east side of the Theller's advance party, while Company H, led by Captain Trimble, deployed in a mounted line on the west side of Theller's position. The civilian volunteers attempted to position themselves on the low ridge line at the eastern end of the cavalry line.

Captain Perry believed his left (eastern) flank to be protected by the volunteers on the ridge from attack. From his position, Perry could not see the position of the volunteers. However, shortly after leaving the main column, the volunteers, now led by George Shearer, encountered warriors hidden in the bushes below and to the east. Shearer ordered his men to dismount and fight on foot. A few obeyed, but the majority left the battle line and fled north out of harm's way. Seeking to protect Perry's command, Shearer led his few remaining men to the top of the ridgeline. In this position, Shearer found himself between the attack on Perry's left flank led by Two Moons and the sniping fire from warriors protecting the White Bird camp.

Perry endeavored to advance to join Theller and charge the Nez Perce warriors menacing his left flank. He ordered carbines to be dropped and pistols drawn for the anticipated charge. He ordered Trumpeter Daly to sound the charge but Daly had lost his trumpet. Perry's means of communications to his troops was lost with the trumpet and the charge never materialized. Perry then determined to make a stand on the ridge line. He ordered a Number fours which caused every fourth man to take the reins of the horses and lead them out of the line of fire into a sheltered location. Perry and the remaining soldiers of Company F then advanced on foot to the ridge line.

Meanwhile, Company H attempted to deploy at five-yard intervals along the ridge while still mounted. This proved disastrous, since the horses were flighty and the troop inexperienced and unable to shoot from the backs of their terrified horses.

Captain Perry, riding back and forth between the two companies, saw the volunteers retreating up the canyon. Several events then occurred that sealed the fate of the cavalry in the Battle of White Bird. Perry's left flank and Trimble's right flank were compromised. Captain Trimble dispatched Sergeant Michael M. McCarthy and six men to the highest point above the battle to protect his right flank. Perry also noticed the high point and attempted to send soldiers to assist McCarthy.[9]

Retreat

[edit]Seeing further collapse of his flank, Perry tried to rally his men to advance to McCarthy's position and make a stand on the high ground about 300 yards (270 m) to the south. But Company F, confused and having suffering numerous casualties, misinterpreted Perry's order as a general retreat. Company H, seeing the urgent retreat of Company F, joined the flight and left McCarthy and his men stranded.

Sensing victory, Ollokot's mounted warriors chased the retreating soldiers. McCarthy, aware that he was cut off from the main detachment, galloped towards the retreating troops. Captain Trimble ordered McCarthy and his six men to return to his position in an attempt to take high ground, but Trimble could not muster any supporting troops for McCarthy's position. McCarthy and his men held off the Nez Perce briefly and then retreated, but were unable to catch up with the main body of Trimbell's company. McCarthy's horse was killed and he survived by hiding in the brush for two days and then walking to Grangeville. He received a Medal of Honor for his role in the battle.[10]

The retreat followed two general routes. Lieutenant Parnell and Lieutenant Theller led squads in an attempt to retrace their approach towards the White Bird camp. Under fire, Theller became trapped in a steep rocky ravine and ran out of ammunition, and he and his seven men were killed by the Nez Perce. Captain Perry and Captain Trimble fled to the northwest up steep ridges. They reached the Camas Prairie on top of the ridge line and were able to regroup at Johnson's Ranch. Within minutes, Nez Perce warriors pressed the attack and the survivors continued their retreat for several miles toward Mount Idaho, where they were rescued by fresh volunteers.[11]

Conclusion

[edit]

at White Bird Canyon

By midmorning, 34 U.S. Cavalry soldiers had been killed and two had been wounded, while two volunteers had also been wounded in the opening of the battle. In contrast, only three Nez Perce warriors had been wounded. Some 63 carbines, many pistols, and hundreds of rounds of ammunition were picked up off the battlefield by Nez Perce warriors. These weapons greatly enhanced the Nez Perce arsenal for the remaining months of the war. Two unknown soldiers from Company F 1st US Cavalry killed in the battle are buried in Custer National Cemetery at Little Bighorn Battlefield Monument.[12] It wasn't until June 27 that Lieutenant Theller's body was found and buried, ten days after he had fallen in the battle. The remains of many of the U.S. Troopers were missing for several days as the dead had fallen over a ten-mile (16 km) stretch of land. Due to the state of decomposition of the dead, the soldiers detailed to bury those dead were required to bury the corpses where they had fallen rather than a mass grave.[13]

The battle in White Bird Canyon was a lopsided victory for the Nez Perce. Outnumbered two to one and fighting uphill with inferior weapons, the Nez Perce used their fighting skills to win the first battle of the Nez Perce War.

Following the battle, the Nez Perce crossed to the east bank of the nearby Salmon River and when General Howard arrived several days later with more than 400 men they taunted him and his soldiers from their side of the river. The Nez Perce, who then numbered about 600 men, women, and children, were expert at river crossings even though accompanied by the elderly, women and children, tipis, personal possessions, and 2,000 horses and other livestock. Howard managed only with difficulty to cross the Salmon with his men to confront the Nez Perce, but rather than fight Howard's superior force, the Indians quickly recrossed the river, leaving Howard stranded on the opposite bank and gaining a head start in their flight to elude the U.S. army.[14]

Battlefield

[edit]White Bird Battlefield | |

| Nearest city | White Bird, Idaho |

|---|---|

| Area | 1,900 acres (7.7 km2) |

| NRHP reference No. | 74000332[15] |

| Added to NRHP | July 18, 1974 |

The White Bird Battlefield is a 1,900 acres (3.0 sq mi; 7.7 km2) area which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.[15][16]

Part or all of it is included in the Nez Perce National Historical Park.

In popular culture

[edit]The Battle of White Bird Canyon is mentioned in the song "The Heart of the Appaloosa" by Fred Small.[17]

References

[edit]- ^ Wilkinson, Charles F. (2005). Blood Struggle: The Rise of Modern Indian Nations. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 40–41. ISBN 0393051498.

- ^ Josephy, Jr., Alvin M. (1965). The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. pp. 428–429.

- ^ McDermott, John D. (1978). Forlorn Hope: The Battle of White Bird Canyon and the Beginning of the Nez Perce War. Boise, ID: Idaho State Historical Society. pp. 57–68, 152–153. ISBN 978-0870044359.

- ^ McDermott, pp. 81–83, 153

- ^ McDermott, p. 83

- ^ McDermott, pp. 54, 73

- ^ McWorter, Lucullus Virgil (1940). "Yellow Wolf: His Own Story". Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers, Ltd. p. 54.

- ^ McDermott, p. 84

- ^ McDermott, pp. 86–91

- ^ Hampton, Bruce (1994). Children of Grace: The Nez Perce War of 1877. New York: Henry Holt and Company. pp. 79–80. ISBN 9780805019919.

- ^ Hampton, pp. 77–78

- ^ "Custer National Cemetery, Crow Agency, Big Horn County, Montana". Interment.net. Archived from the original on April 26, 2012. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

- ^ Sharfstein, Daniel (2019). Thunder in the Mountains. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. p. 253.

- ^ Greene, Jerome A. (2000). "2". Nez Perce Summer 1877: The U.S. Army and the Nee-Me-Poo Crisis. Helena: Montana Historical Society Press. ISBN 0917298683.

- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ Jack R. Williams (March 15, 1973). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: White Bird Battlefield Site 13 / Nez Perce National Historical Park". National Park Service. Retrieved September 2, 2017. With photo from 1973.

- ^ Bogdanov, Vladimir; Woodstra, Chris; Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (2001). All Music Guide: The Definitive Guide to Popular Music. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-0-87930-627-4.

External links

[edit]- Nez Perce National Historical Park

- Wild West magazine, The Battle of White Bird Canyon: First Fight of the Nez Perce - accessed 25 Jul 2014

- WildWest Magazine, The Battle of White Bird Canyon - No longer available as of 26 July 2012

- McDermott, John Dishon (June 1, 1968). "FORLORN HOPE: A Study of the Battle of White Bird Canyon Idaho and the Beginning of the Nez Perce Indian War". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 28 May 2009. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

Bibliography

[edit]- West, Elliott (2009). The last Indian war : the Nez Perce story. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195136753.

- Greene, Jerome A. (2000). A Nez Perce Summer 1877. Helena: Montana Historical Society Press. Accessed 27 Jan 2012

- Hampton, Bruce (1994). Children of Grace: The Nez Perce War of 1877. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

- Sharfstein, Daniel (2019). Thunder in the Mountains. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

- West, Elliot (2011). Last Indian War: The Nez Perce Story. New York: Oxford University Press.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch