Bennerley Viaduct

Bennerley Viaduct | |

|---|---|

Bennerley Viaduct in 2010 | |

| Coordinates | 52°59′22″N 1°17′55″W / 52.989538°N 1.298532°W |

| Carries | Formerly Great Northern Railway; now foot traffic |

| Crosses | River Erewash |

| Locale | Awsworth/Ilkeston (near Nottingham) |

| Maintained by | Railway Paths Ltd |

| Heritage status | Grade II* listed building |

| Characteristics | |

| Total length | 1,421 feet (433 m) |

| Width | 26 ft (8 m) |

| Height | 60 feet (18 m) |

| History | |

| Construction start | May 1876 |

| Construction end | November 1877 |

| Opened | January 1878 |

| Location | |

| |

Bennerley Viaduct (originally Ilkeston Viaduct[1] and known informally as the Iron Giant[2]) is a former railway bridge, now a foot and cycle bridge, between Ilkeston, Derbyshire, and Awsworth, Nottinghamshire, in central England. It was completed in 1877 and carried the Great Northern Railway's (GNR) Derbyshire Extension over the River Erewash, which forms the county boundary, and its wide, flat valley. The engineer was Samuel Abbott, who worked under Richard Johnson, the GNR's chief engineer. The site required a bespoke design as the ground would not support a traditional masonry viaduct due to extensive coal mining. The viaduct consists of 16 spans of wrought iron, lattice truss girders, carried on 15 wrought iron piers which are not fixed to the ground but are supported by brick and ashlar bases. The viaduct is 60 feet (18 metres) high, 26 feet (8 metres) wide between the parapets, and over a quarter of a mile (400 metres) long. It was once part of a chain of bridges and embankments carrying the railway for around two miles (three kilometres) across the valley but most of its supporting structures were demolished when the line closed in 1968. The only similar surviving bridge in the United Kingdom is Meldon Viaduct in Devon.

The viaduct opened in January 1878. Its working life was uneventful except for minor damage inflicted by a Zeppelin bombing raid during the First World War. Plans to demolish the viaduct failed because of the cost of dismantling the ironwork and it became a listed building in 1974. After closure, the viaduct received little maintenance and fell into disrepair. Railway Paths, a walking and cycling charity, acquired it for preservation in 2001 but work faltered due to a lack of funding. The viaduct was listed on the Heritage at Risk Register in 2007 and the 2020 World Monuments Watch for its condition and lack of use. A detailed survey was undertaken in 2016 and funding for restoration work was secured in 2019. The work included rebuilding an embankment to allow step-free access. It opened to the public as part of a cycling and walking route in January 2022.

Background

[edit]Most of the viaduct is in Awsworth, Nottinghamshire, but the western end is just north of Ilkeston in Derbyshire; the River Erewash forms the boundary between the two counties. The viaduct was built for the Great Northern Railway's (GNR) Derbyshire Extension, which opened in 1878. The company's stronghold was previously the eastern side of England between London and York, though it had lines as far west as Nottingham, and it was keen to expand westwards to access the coal fields of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, an area which had previously been monopolised by the Midland Railway. The main line of the extension ran from Nottingham Victoria railway station to Burton upon Trent railway station via Derby Friargate railway station.[3][4][5]

The route involved significant civil engineering works. The Midland Railway already occupied the most obvious paths and so the GNR had to take a more difficult route, which required multiple bridges, tunnels, and viaducts. Among several branches from the main route, one diverged just east of Awsworth and continued north up the Erewash Valley; another served Bennerley Ironworks (since demolished). Bennerley Viaduct was built immediately south of the ironworks site, which is roughly mid-way between Nottingham and Derby. It was the second-largest engineering work on the GNR's East Midlands routes after the Giltbrook Viaduct on the Awsworth branch, which was a more traditional brick viaduct and demolished after the line's closure.[6][7]

Bennerley was one of several wrought iron viaducts built in the period after cast iron fell out of favour for bridge building following the 1847 Dee Bridge disaster, but before steel became commonplace.[3] The crossing of the River Erewash and its wide, flat valley required a bespoke solution—the valley is boggy and undermined by extensive coal workings which were poorly mapped. The ground would not have been able to support a conventional brick or masonry structure. Thus, Bennerley Viaduct was designed to be lightweight to minimise the load on the foundations.[8][9]

The viaduct was designed by Samuel Abbott, a Nottinghamshire-born engineer and the GNR's resident engineer on the Derbyshire Extension, with input from Richard Johnson, the GNR's chief engineer. Abbot and Johnson were also responsible for Handyside Bridge and Friar Gate Bridge in Derby, further west on the same line. The contractor was Benton and Woodiwiss, and the wrought iron was supplied by Eastwood Swingler & Company of Derby.[3][8][10]

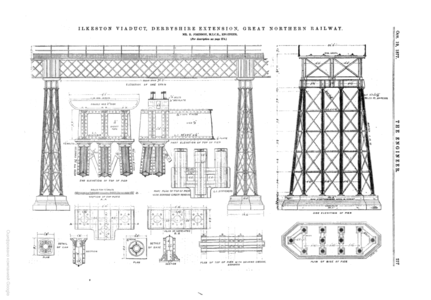

- Technical drawings of the viaduct, published in The Engineer

Description

[edit]

According to Graeme Bickerdike, writing in 2016 in the magazine Rail Engineer, the design was based on the Viaduc de Busseau, opened in 1864, in central France.[11] The bridge deck consists of 16 spans, each 77 feet (23 metres) long and formed from four 8-foot (2.4-metre) deep wrought-iron Warren lattice truss girders braced together horizontally and vertically. The trusses support a series of transverse iron troughs at 2-foot-4-inch (0.71-metre) centres.[1][11][12] Because of the corrugated surface provided by the troughs, the volume of track ballast required was half that of a traditional flat-decked bridge.[13][14] The rails were not fixed to the bridge deck, instead lying directly on the ballast. The bridge deck is enclosed by low wrought-iron latticework parapets.[3][8][11]

The spans are supported on 15 evenly spaced piers of the same height, 56 feet (17 metres). The piers rest on concrete foundations but are not bolted down. They are held in place by blue brick and ashlar bases, which were built around them. The lack of fixity allows slight movement of the structure to compensate for the ground conditions. Any misalignment of the tracks could be rectified by repacking the ballast.[3][8][1][13] The piers are formed of 12 wrought-iron tubular columns, each constructed from four quadrant pieces riveted together.[1] The tubes are arranged in four groups of three. The centre-most two groups consist of a central vertical column with a slightly inclined column either side of it longitudinally; in the two outermost groups the central columns are offset transversely as raking columns to provide lateral support. The tube groups are braced together horizontally and vertically at four stages.[8][1]

The viaduct is 1,421 feet (433 metres) long (over a quarter of a mile), 60 feet (18 metres) above the valley floor in the centre, and 26 feet (8 metres) wide between the parapets. Both ends of the viaduct are supported on brick piers.[3][8] The structure provides a constant 1:100 gradient; the Awsworth end is 15 feet (4.6 metres) higher than the Ilkeston end.[15] It was once the central (and longest) part of a roughly 2-mile (3.2-kilometre) section of raised line over the Erewash Valley. The valley was approached on embankments at each end. At the western (Ilkeston) end, another iron bridge, supported on Bennerley Viaduct's western pier, continues the line of the viaduct across the Erewash Valley line (built by the Midland Railway and still in use); that bridge is a plate girder structure at a 15-degree skew. A brick bridge continued the line over the Erewash Canal towards Derby but this was demolished after the railway's closure. The terminating brick pier at the eastern (Awsworth) end was built into an embankment on which the line continued towards Nottingham. The embankments were also demolished, though stubs remain at both ends and between the viaduct and the canal.[8][13][16] Aside from the demolition of its surrounding structures, the viaduct survives in a largely unaltered state.[8] The Erewash Valley is largely flat, making Bennerley Viaduct the dominant feature in the landscape. The only nearby patch of high ground is Ilkeston town centre, around two miles (three kilometres) to the south.[17]

- Features of the viaduct

- The latticework parapet where the viaduct crosses the River Erewash

- The corrugated bridge deck (seen before the viaduct was converted to a foot and cycle bridge)

- The underside of the bridge deck, showing the multiple trusses that make up each segment

- The bottom of a pier, showing the concrete and brick base

History

[edit]Construction on the viaduct began with the foundations in May 1876 and the work was completed 18 months later in November 1877. The railway line opened in January 1878. The viaduct's operational life was largely uneventful.[8][11]

On 31 January 1916, nine Zeppelin airships of the German Airship Naval Division conducted a bombing raid over the English Midlands known as the Great Midlands Raid. One of these airships, the L.20 (LZ 59), dropped seven high-explosive bombs in the vicinity of Bennerley Viaduct. One landed just to the north of the viaduct on the Midland Railway line at Bennerley Junction, destroying a signal box on the Midland line. One pier of the viaduct was hit by shrapnel, causing superficial damage; the marks are still visible on one of the piers.[11][18]

In the 1960s, the British railway industry, which had been nationalised in 1948, was in decline and the Derbyshire Extension was considered unnecessarily duplicative. Passenger services were withdrawn in 1964 and Bennerley Viaduct closed altogether, along with the rest of the line, in 1968 as a result of the Beeching cuts. Most of the other structures carrying the line across the valley were demolished. A contractor was appointed to demolish Bennerley Viaduct but wrought iron cannot be cut up using conventional metal-cutting equipment and it would therefore have to be dismantled piece by piece. The cost was deemed prohibitive and the viaduct remained in situ.[8][4][11][19]

Bennerley Viaduct became part of the closed-line estate, a group of redundant railway structures maintained by the railway authorities to ensure they did not pose a risk to the public. The derelict land around the bridge became a wildlife haven, though the area also attracted anti-social behaviour and there were several incidents involving people attempting to climb the piers and falling off.[20] As a result of the privatisation of British Rail in the 1990s, the viaduct became part of the Historical Railways Estate (or Burdensome Estate), managed by BRB (Residuary) Limited. By that time, there were advanced plans for a conservation group to take ownership of it.[21] In 2001, Railway Paths Ltd, a sister charity of Sustrans formed to conserve redundant railway structures and convert them into walking and cycling paths, purchased the viaduct from BRB (Residuary).[22][23]

Restoration

[edit]

The viaduct was designated a Grade II listed building in 1974, later upgraded to Grade II*. It is listed for its architectural interest, rarity, constructional interest, and completeness. Listed status provides legal protection from demolition or unsympathetic modification.[8] British Rail applied for planning permission to demolish the viaduct in 1975 and 1980, partly due to persistent trespass—there were several incidents of people injuring themselves after falling from the viaduct—but both applications were rejected.[11][23] The viaduct received little maintenance after 1986 and fell into disrepair. Repair and conservation schemes were mooted but with little progress.[19] In 2007, the viaduct was added to the Heritage at Risk Register as its condition had deteriorated to the point that it was in danger of irreparable damage,[24][25] and it was the only site in the United Kingdom on the 2020 World Monuments Watch, a list published by the World Monuments Fund to highlight heritage sites "in need of urgent action that demonstrate the potential to trigger social change through conservation".[23][26]

A detailed condition survey was undertaken in 2016, following volunteer work to clear vegetation from the bases of the piers. The survey revealed the viaduct to be in generally good condition. It noted corrosion to the ends of the troughs on the bridge deck, damage to brickwork from frost weathering, and missing rivets among the minor defects.[11] In 2017, the Heritage Lottery Fund gave an initial grant to promote engagement and interpretation, which led to the formation of the Friends of Bennerley Viaduct, a community group which works alongside Railway Paths on the restoration and preservation of the viaduct. An application for further Heritage Lottery funding to enable the viaduct to be opened to the public was rejected at the end of 2017, leaving it with an uncertain future.[23][27] In 2019 Historic England offered £120,000 to cover a funding shortfall, allowing restoration work to begin the following year.[28] Ben Robinson, Historic England's Principal Advisor for Heritage at Risk, said "The importance of this viaduct cannot be underplayed. [It is] a stunning example of the genius of British engineering".[29]

The work included repairs to the ironwork, the bases of the piers, and abutments and partial reconstruction of the parapets at the eastern end. The embankment at the western end was rebuilt to provide ramped access from the Erewash Canal towpath and steps were built from the eastern end with a wheel trough alongside for bicycles.[22][29] The viaduct twice featured on the television series The Architecture the Railways Built, once in the inaugural episode in 2020 and once during the restoration work.[30][31][32] It opened to walkers and cyclists on 13 January 2022 after the completion of work costing £1.7 million, which was contributed by Railway Paths, the Railway Heritage Trust, and others.[19] In January 2023, funding was awarded towards creating ramped access from the Awsworth end.[33] As of January 2025, the ramp, initially expected to be completed in late 2024, was experiencing further delay due to safety concerns with no definite completion date anticipated.[34][35]

Appreciation and influence

[edit]

The only other surviving wrought-iron lattice viaduct in the United Kingdom is Meldon Viaduct, near Okehampton, in Devon. Meldon is significantly taller but less than half the length.[3][8][36][37] The railway historians Gordon Biddle and O. S. Nock described Bennerley as "by far the more attractive" of the two.[38] Meldon Viaduct has been significantly altered since it was built, whereas Bennerley is essentially unchanged.[8] Belah Viaduct in Cumbria had a similar design but was demolished shortly after its closure in 1962.[21] Another wrought-iron bridge was Crumlin Viaduct, once Britain's tallest, in South Wales. This too was demolished in the 1960s despite efforts to preserve it.[9][39]

Gregory Beecroft, a senior project surveyor for the British Rail Property Board, described Bennerley Viaduct in a contribution for a 1997 book as "among the least impressive" of several metal viaducts that once stood on the British railway network, contrasting it in particular with Belah Viaduct. He believed that "in retrospect, it is a pity that the resources now to be devoted to Bennerley could not have been used to preserve Belah Viaduct. [...] Belah Viaduct closed in 1962, when we were less conscious of our railway heritage, and it was demolished not long after".[21] Historic England calls Bennerley Viaduct "an outstanding survival of the mature phase of development of the railway network in England, demonstrating the confidence of railway engineers in seeking solutions to specific engineering challenges".[8] The journalist Matthew Parris (formerly a Derbyshire MP) visited during restoration work in 2021, and wrote in a column for The Times: "It is, on one view, a hideous thing; and on another a precious and remarkable monument to early railway engineering".[40]

The author D. H. Lawrence grew up in the Erewash Valley and used it as a backdrop to many of his works. He references Bennerley Viaduct in several, most prominently in the novel Sons and Lovers, which includes the lines "There was a faint rattling noise. Away to the right the train, like a luminous caterpillar, was threading across the night. The rattling ceased. 'She's over the viaduct. You'll just do it.' "[20][40]

See also

[edit]- Route diagram of the Derbyshire Extension (Bennerley Viaduct is immediately east of where the extension crosses the Erewash Valley line)

- Grade II* listed buildings in Erewash

- Grade II* listed buildings in Nottinghamshire

- Listed buildings in Awsworth

- Listed buildings in Ilkeston

- List of lattice girder bridges in the United Kingdom

References

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Barton, Barry (2016). Civil Engineering Heritage: East Midlands. Lincoln: Ruddock's. ISBN 9780904327243.

- Beecroft, Gregory (1997). "How British Rail Property Board manages the closed-line estate". In Burman, Peter; Stratton, Michael (eds.). Conserving the Railway Heritage. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 9780419212805.

- Biddle, Gordon (2011). Britain's Historic Railway Buildings: A Gazetteer of Structures (Second ed.). Hersham: Ian Allan. ISBN 9780711034914.

- Biddle, Gordon; Nock, O. S. (1983). The Railway Heritage of Britain: 150 Years of Railway Architecture and Engineering. London: Sheldrake Press. ISBN 9780718123550.

- Cossons, Neil; Trinder, Barrie (2002). The Iron Bridge: Symbol of the Industrial Revolution (Second ed.). Chichester: Phillimore. ISBN 9781860772306.

- Hartwell, Clare; Pevsner, Nikolaus; Williamson, Elizabeth (2020) [1979]. Nottinghamshire. The Buildings of England. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300247831.

- Henshaw, Alfred (2000). The Great Northern Railway in the East Midlands. Huntingdon: Railway Correspondence and Travel Society. ISBN 9780901115881.

- Higginson, Mark (1989). The Friargate Line: Derby and the Great Northern Railway. Derby: Golden Pingle. ISBN 9780951383407.

- Labrum, E. A. (1994). Civil Engineering Heritage: Eastern and Central England. London: Thomas Telford. ISBN 9780727719706.

- McFetrich, David (2019). An Encyclopaedia of British Bridges (Revised and extended ed.). Barnsley: Pen and Sword Books. ISBN 9781526752956.

- Owens, Victoria (2019). Aqueducts and Viaducts of Britain. Stroud: Amberley. ISBN 9781445683805.

- Wynch, Jeff (2023). Bennerley Viaduct, The Iron Giant of the Erewash Valley. Ilkeston: Friends of Bennerley Viaduct. ISBN 9780860719120.

- Yee, Ronald (2021). The Architecture of British Bridges. Ramsbury: The Crowood Press. ISBN 9781785007941.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Ilkeston Viaduct". The Engineer. Vol. 44. 19 October 1877. pp. 274–276.

- ^ Harby, Jennifer (7 August 2022). "Bennerley Viaduct marks its restoration year". BBC News. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Labrum, pp. 26–28.

- ^ a b Owens, p. 58.

- ^ Henshaw, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Henshaw, p. 90.

- ^ Higginson, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Historic England. "Bennerley Viaduct (1140437)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ a b Cossons & Trinder, p. 104.

- ^ Hartwell, Pevsner, & Williamson, p. 110.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bickerdike, Graeme (December 2016). "Bennerley's New Dawn". Rail Engineer. No. 146. pp. 76–80.

- ^ McFetrich, p. 43.

- ^ a b c Yee, p. 109.

- ^ Barton, p. 115.

- ^ "Bennerley Viaduct: A Bespoke Design". Friends of Bennerley Viaduct. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ Barton, p. 116.

- ^ Biddle & Nock, p. 80.

- ^ "Zeppelin Attack". Friends of Bennerley Viaduct. Archived from the original on 1 February 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Watson, Greig; Barnes, Liam (13 January 2022). "Bennerley Viaduct reopens to public after £1.7m repairs". BBC News. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ a b Seddon, Peter (9 September 2019). "Saving Bennerley Viaduct, a rare historic gem". Great British Life. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ a b c Beecroft, p. 218.

- ^ a b "Bennerley Viaduct". Railway Paths. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d Hakimian, Rob (14 January 2022). "Bennerley rail viaduct opens for pedestrians and cyclists after half-century of disrepair". New Civil Engineer. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ "Historic building risk list grows". BBC News. 24 July 2007. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ "Bennerley Viaduct, Awsworth Road (part located in Erewash Borough), Awsworth". Historic England. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ "Bennerley Viaduct makes global 'at risk' heritage list". BBC News. 29 October 2019. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ Taylor, Alun (21 March 2018). "Fancy a viaduct? We have a wrought Victorian iron marvel to sell you". The Register. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ Mitchell, Hannah (8 April 2019). "Iconic viaduct on edge of Ilkeston set to reopen for first time in 50 years". Derby Telegraph. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ a b "'At risk' Bennerley Viaduct repairs to begin". BBC News. 2 February 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ Roberts, Lucy (18 February 2021). "Iconic Derbyshire viaduct set to feature in TV documentary series". Derbyshire Times. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ Ram, Phoebe (4 April 2021). "Hopes for viaduct to reopen this year after five decades of closure". Nottingham Post. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ "Iron Giant Stars in TV Broadcast". Friends of Bennerley Viaduct. 4 March 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ Harby, Jennifer; Torr, George; Bevis, Gavin (19 January 2023). "Levelling up: Joy and disappointment at funding announcement". BBC News. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ Opening of historic viaduct ramp delayed further BBC News, 16 October 2024. Retrieved 17 January 2025

- ^ Months until delayed viaduct ramp opens - charityBBC News, 12 January 2025. Retrieved 17 January 2025

- ^ Biddle, p. 321.

- ^ Banerjee, Jacqueline; Price, Colin (1 April 2022). "The Bennerley Viaduct (1876–77)". Victorian Web. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- ^ Biddle & Nock, p. 239.

- ^ Owens, p. 57.

- ^ a b Parris, Matthew (23 June 2021). "Friends in high places saved our iron skyway". The Times. Archived from the original on 23 June 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch