Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux | |

|---|---|

San Bernardo by Juan Correa de Vivar, held in the Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain | |

| |

| Born | c. 1090 Fontaine-lès-Dijon, Burgundy, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 20 August 1153 (aged 62–63) Clairvaux Abbey, Clairvaux, Champagne, Kingdom of France |

| Venerated in | |

| Canonized | 18 January 1174, Rome, Papal States, by Pope Alexander III |

| Major shrine | Troyes Cathedral |

| Feast | 20 August |

| Attributes | |

| Patronage | |

| Part of a series on |

| Christian mysticism |

|---|

|

Bernard of Clairvaux, O.Cist. (Latin: Bernardus Claraevallensis; 1090 – 20 August 1153), venerated as Saint Bernard, was an abbot, mystic, co-founder of the Knights Templar,[a] and a major leader in the reform of the Benedictines through the nascent Cistercian Order.

He was sent to found Clairvaux Abbey only a few years after becoming a monk at Cîteaux. In the year 1128, Bernard attended the Council of Troyes, at which he traced the outlines of the Rule of the Knights Templar, which soon became an ideal of Christian nobility.

On the death of Pope Honorius II in 1130, a schism arose in the church. Bernard was a major proponent of Pope Innocent II, arguing effectively for his legitimacy over the Antipope Anacletus II.

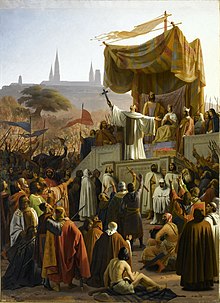

The eloquent abbot advocated crusades in general and convinced many to participate in the unsuccessful Second Crusade, notably through a famous sermon at Vézelay (1146).

Bernard was canonized just 21 years after his death by Pope Alexander III. In 1830 Pope Pius VIII declared him a Doctor of the Church.

Early life (1090–1113)

[edit]Bernard's parents were Tescelin de Fontaine, lord of Fontaine-lès-Dijon, and Alèthe de Montbard, both members of the highest nobility of Burgundy. Bernard was the third of seven children, six of whom were sons. Aged nine, he was sent to a school at Châtillon-sur-Seine run by the secular canons of Saint-Vorles. Bernard had an interest in literature and rhetoric.

Bernard's mother died when he was a youth. During his education with priests, he often thought of becoming one. In 1098, a group led by Robert of Molesme had founded Cîteaux Abbey, near Dijon, with the purpose of living according to a literal interpretation of the Rule of St. Benedict. They established new administrative structures among their monasteries, effectively creating a new order, known, after the first abbey, as the Order of Cistercians.[3] After his mother died, Bernard decided to go to Cîteaux. In 1113 he and thirty other young noblemen of Burgundy, many of whom were his relatives, sought and gained admission to the new monastery.[4] Bernard's example was so convincing that scores (among them his own father) followed him into the monastic life.[5] As a result, he is considered the patron of religious vocations.[6]

Abbot of Clairvaux

[edit]

The little community of reformed Benedictines at Cîteaux grew rapidly. Three years after entering, Bernard was sent with a group of twelve monks to found a new house at Vallée d'Absinthe, in the Diocese of Langres. This Bernard named Claire Vallée, or Clairvaux, on 25 June 1115, and the names of Bernard and Clairvaux soon became inseparable. Bernard was made abbot by William of Champeaux, Bishop of Châlons-sur-Marne. From then on a strong friendship grew between the abbot and the bishop, who was professor of theology at Notre Dame of Paris and the founder of St. Victor Abbey in Paris.[7]

The beginnings of Clairvaux Abbey were austere and Bernard even more so. He had often been ill since his noviciate, due to extreme fasting. Nonetheless, candidates for the monastic life flocked to him in great numbers. Clairvaux soon started founding new communities.[8] In 1118 Trois-Fontaines Abbey was founded in the diocese of Châlons; in 1119 Fontenay Abbey in the Diocese of Autun; and in 1121 Foigny Abbey near Vervins. In Bernard's lifetime, more than sixty abbeys followed, though some were not new foundations but transferals to the Cistercians.[9]

Bernard spent extended time outside of the abbey as a preacher and a diplomat in the service of the pope. Described by Jean-Baptiste Chautard as "the most contemplative and yet at the same time the most active man of his age,"[10] Bernard described the disparate parts of his personality when he called himself the "chimera of his age."[11]

In addition to successes, Bernard also had his trials. Once, when he was absent from Clairvaux, the prior of the rival Abbey of Cluny went to Clairvaux and convinced Bernard's cousin, Robert of Châtillon, to become a Benedictine. This was the occasion of the longest and most emotional of Bernard's letters.[7] When his brother Gerard died, Bernard was devastated, and his deep mourning was the inspiration for one of his most moving sermons.[12]

The Cluny Benedictines were unhappy to see Cîteaux gain such prominence so quickly, particularly since many Benedictines were becoming Cistercians. They criticized the Cistercian way of life. At the solicitation of William of St.-Thierry, Bernard defended the Cistercians with his Apology. Peter the Venerable, abbot of Cluny, answered Bernard and assured him of his admiration and friendship. In the meantime, Cluny launched a reform and Bernard befriended Abbot Suger.[13]

Doctor of the Church

[edit]

Although acknowledged as "a difficult saint,"[14] Bernard has remained influential in the centuries since his death and was named a Doctor of the Church in 1830. In 1953, on the 800th anniversary of his death, Pope Pius XII devoted the encyclical Doctor Mellifluus to him. He labeled the abbot "the last of the Fathers."[15]

In opposition to the rational approach to understanding God used by the scholastics, Bernard preached in a poetic manner, using appeals to affect and conversion to nurture a more immediate faith experience. He is considered to be a master of Christian rhetoric: "His use of language remains perhaps his most universal legacy."[16] He contributed lyrics to the Cistercian Hymnal.

As a mariologist, Bernard insisted on Mary's central role in Christian theology and preached effectively on Marian devotions. He developed the theology of her role as Co-Redemptrix and mediator.[17]

As a master of prayer, the abbot emphasized the value of personal, experiential friendship with Christ.[18]

Schism

[edit]Bernard made a self-confident impression and had an undeniable charisma in the eyes of his contemporaries; "his first and greatest miracle," wrote the historian Holdsworth, "was himself."[19] He defended the rights of the church against the encroachments of kings and princes, and recalled to their duty Henri Sanglier, archbishop of Sens and Stephen of Senlis, bishop of Paris. When Honorius II died in 1130, a schism broke out in the Church by the election of two popes, Pope Innocent II and Antipope Anacletus II. Innocent, having been banished from Rome by Anacletus, took refuge in France. King Louis VI convened a national council of the French bishops at Étampes and Bernard, summoned there by the bishops, was chosen to judge between the rival popes. He decided in favour of Innocent.[20]

Bernard travelled on to Italy and reconciled Pisa with Genoa, and Milan with the pope. The same year Bernard was again at the Council of Reims at the side of Innocent II. He then went to Aquitaine where he succeeded for the time in detaching William X, Duke of Aquitaine, from the cause of Anacletus.

Germany had decided to support Innocent through Norbert of Xanten, who was a friend of Bernard's. Pope Innocent, however, insisted on Bernard's company when he met with Lothair II, Holy Roman Emperor. Lothair II became Innocent's strongest ally among the nobility. Although the councils of Étampes, Würzburg, Clermont, and Rheims all supported Innocent, large portions of the Christian world still supported Anacletus.

In a letter by Bernard to German Emperor Lothair regarding Antipope Anacletus, Bernard wrote, "It is a disgrace for Christ that a Jew sits on the throne of St. Peter's" and "Anacletus has not even a good reputation with his friends, while Innocent is illustrious beyond all doubt." (One of Anacletus' great-great-grandparents, Benedictus, maybe Baruch in Hebrew, was a Jew who had converted to Christianity - but Anacletus himself was not a Jew, and his family had been Christians for three generations).[21]

Bernard wrote to Gerard of Angoulême (a letter known as Letter 126), which questioned Gerard's reasons for supporting Anacletus. Bernard later commented that Gerard was his most formidable opponent during the whole schism. After persuading Gerard, Bernard travelled to visit William X, Duke of Aquitaine. He was the hardest for Bernard to convince. He did not pledge allegiance to Innocent until 1135. After that, Bernard spent most of his time in Italy persuading the Italians to pledge allegiance to Innocent.

In 1132, Bernard accompanied Innocent II into Italy, and at Cluny, the pope abolished the dues which Clairvaux used to pay to that abbey. This action gave rise to a quarrel between the White Monks and the Black Monks which lasted 20 years. In May of that year, the pope, supported by the army of Lothair III, entered Rome, but Lothair III, feeling himself too weak to resist the partisans of Anacletus, retired beyond the Alps, and Innocent sought refuge in Pisa in September 1133. Bernard had returned to France in June and was continuing the work of peacemaking which he had commenced in 1130.

Towards the end of 1134, he made a second journey into Aquitaine, where William X had relapsed into schism. Bernard invited William to the Mass which he celebrated in the Church of La Couldre. At the Eucharist, he "admonished the Duke not to despise God as he did His servants".[7] William yielded and the schism ended.

Bernard went again to Italy, where Roger II of Sicily was endeavouring to withdraw the Pisans from their allegiance to Innocent. He recalled the city of Milan to obedience to the pope as they had followed the deposed Anselm V, Archbishop of Milan. For this, he was offered, and he refused, the see of Milan. He then returned to Clairvaux. Believing himself at last secure in his cloister, Bernard devoted himself to the composition of the works which won him the title of "Doctor of the Church". He wrote at this time his sermons on the Song of Songs.[b]

In 1137, he was again forced to leave the abbey by order of the pope to put an end to the quarrel between Lothair and Roger of Sicily. At the conference held at Palermo, Bernard succeeded in convincing Roger of the rights of Innocent II. He also silenced the final supporters who sustained the schism. Anacletus died of "grief and disappointment" in 1138, and with him, the schism ended.[7][23]

In 1139, Bernard assisted at the Second Council of the Lateran, in which the surviving adherents of the schism were definitively condemned. About the same time, Bernard was visited at Clairvaux by Malachy, Primate of All Ireland, and a very close friendship formed between them. Malachy wanted to become a Cistercian, but the pope would not give his permission. Malachy died at Clairvaux in 1148.[7]

Conflict with Abelard

[edit]Towards the close of the 11th century, a spirit of independence flourished within schools of philosophy and theology. The movement found an ardent and powerful advocate in Peter Abelard. Abelard's treatise on the Trinity had been condemned as heretical in 1121, and he was compelled to throw his own book into a fire. However, Abelard continued to develop his controversial teachings. Bernard is said to have held a meeting with Abelard intending to persuade him to amend his writings, during which Abelard repented and promised to do so. But once out of Bernard's presence, he reneged.[24]

Bernard then denounced Abelard to the pope and cardinals of the Curia. Abelard sought a debate with Bernard, but Bernard initially declined, saying he did not feel matters of such importance should be settled by logical analyses. Bernard's letters to William of St-Thierry also express his apprehension about confronting the preeminent logician. Abelard continued to press for a public debate, and made his challenge widely known, making it hard for Bernard to decline. In 1141, at the urgings of Abelard, the archbishop of Sens called a council of bishops, where Abelard and Bernard were to put their respective cases so Abelard would have a chance to clear his name.[24]

Bernard lobbied the prelates on the evening before the debate, swaying many of them to his view. The next day, after Bernard made his opening statement, Abelard decided to retire without attempting to answer.[24] The council found in favour of Bernard and their judgment was confirmed by the pope. Abelard submitted without resistance, and he retired to Cluny to live under the protection of Peter the Venerable, where he died two years later.

The challenge of heresy

[edit]Bernard had occupied himself in sending bands of monks from his overcrowded monastery into Germany, Sweden, England, Ireland, Portugal, Switzerland, and Italy. Some of these, at the command of Innocent II, took possession of Tre Fontane Abbey, from which Eugene III was chosen in 1145. Pope Innocent II died in the year 1143. His two successors, Pope Celestine II and Pope Lucius II, reigned only a short time, and then Bernard saw one of his disciples, Bernard of Pisa, known thereafter as Eugene III, raised to the Chair of Saint Peter. Bernard sent him, at the pope's own request, various instructions which comprise the often-quoted De consideratione. Its main argument is that church reform ought to start with the pope. Temporal matters are merely accessories; Bernard insists that piety and meditation were to precede action.[25]

Having previously helped end the schism within the Church, Bernard was now called upon to combat heresy. Henry of Lausanne, a former Cluniac monk, had adopted the teachings of the Petrobrusians, followers of Peter of Bruys and spread them in a modified form after Peter's death. Henry of Lausanne's followers became known as Henricians. In June 1145, at the invitation of Cardinal Alberic of Ostia, Bernard travelled in southern France. His preaching, aided by his ascetic looks and simple attire, helped doom the new sects. Both the Henrician and the Petrobrusian faiths began to die out by the end of that year. Soon afterwards, Henry of Lausanne was arrested, brought before the bishop of Toulouse, and probably imprisoned for life. In a letter to the people of Toulouse, undoubtedly written at the end of 1146, Bernard calls upon them to extirpate the last remnants of the heresy. He also preached against Catharism. Prior to the second hearing of Gilbert of Poitiers at the Council of Reims 1148, Bernard held a private meeting with a number of the attendees, attempting to pressure them to condemn Gilbert. This offended the various cardinals in attendance, who then proceeded to insist that they were the only persons who could judge the case, and no verdict of heresy was placed against Gilbert.

Monastic and clerical preaching

[edit]As abbot, Bernard often addressed his community, but he also spoke to other monastics and, in one particularly famous case, to students of Theology in Paris. He gave the sermon Ad clericos de conversione (to clerics on conversion) in 1139 or early 1140, to a group of scholars and student clerics.[26] His many sermons on the Song of Songs belong to the often-studied sermons he addressed to the monks at Clairvaux.[27]

Crusade preaching

[edit]Second Crusade (1146–1149)

[edit]

News came at this time from the Holy Land that alarmed Christendom. Christians had been defeated at the Siege of Edessa and most of the county had fallen into the hands of the Seljuk Turks.[28] The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the other Crusader states were threatened with similar disaster. Deputations of the bishops of Armenia solicited aid from the pope, and the King of France also sent ambassadors. In 1144 Eugene III commissioned Bernard to preach the Second Crusade and granted the same indulgences for it which Pope Urban II had accorded to the First Crusade.[29]

There was at first virtually no popular enthusiasm for the crusade as there had been in 1095. Bernard found it expedient to dwell upon taking the cross as a potent means of gaining absolution for sin and attaining grace. On 31 March, with King Louis VII of France present, he preached to an enormous crowd in a field at Vézelay, making "the speech of his life".[30] When he had finished, many of his listeners enlisted; they supposedly ran out of the cloth used to make crosses for the new recruits.[29][30]

Unlike the First Crusade, the new venture attracted royalty, such as the French queen Eleanor of Aquitaine and scores of high aristocrats and bishops. But an even greater show of support came from the common people. Bernard wrote Pope Eugene a few days afterwards, "Cities and castles are now empty. There is not left one man to seven women, and everywhere there are widows to still-living husbands."[31]

Bernard then passed into Germany, with reported miracles contributing to the success of his mission. King Conrad III of Germany and his nephew Frederick Barbarossa, received the cross from the hand of Bernard.[28] Pope Eugenius came in person to France to encourage the enterprise. As in the First Crusade, the preaching led to attacks on Jews; a fanatical French monk named Radulf was apparently inspiring massacres of Jews in the Rhineland, Cologne, Mainz, Worms, and Speyer, with Radulf claiming Jews were not contributing financially to the rescue of the Holy Land. The archbishop of Cologne and the archbishop of Mainz were vehemently opposed to these attacks and asked Bernard to denounce them. This he did, but when the campaign continued, Bernard travelled from Flanders to Germany to deal with the problems in person. He then found Radulf in Mainz and was able to silence him, returning him to his monastery.[32]

The last years of Bernard's life were saddened by the failure of the Second Crusade he had preached, and the entire responsibility which was thrown upon him. Bernard sent an apology to the Pope and it is inserted in the second part of his "Book of Considerations". There he explains how the sins of the crusaders were the cause of their misfortune and failures.

Wendish Crusade (1147)

[edit]Bernard did not actually preach the Wendish Crusade, but he did write a letter that advocated subduing this group of Western Slavs so that they should not be an obstacle to the Second Crusade. He was for battling them "until such a time as, by God's help, they shall either be converted or deleted".[33] A decree issued in Frankfurt stated that the letter should be proclaimed widely and read aloud, so that "the letter functioned as a sermon."[34]

Final years (1149–1153)

[edit]

The death of his contemporaries served as a warning to Bernard of his own approaching end. The first to die was Suger in 1152, of whom Bernard wrote to Eugene III, "If there is any precious vase adorning the palace of the King of Kings it is the soul of the venerable Suger."[35] Conrad III and his son Henry died the same year. Bernard died at age sixty-three on 20 August 1153, after forty years of monastic life. He was buried at Clairvaux Abbey. After its destruction in 1792 by the French Revolutionary government his remains were transferred to Troyes Cathedral.

Legacy

[edit]Bernard's theology and Mariology continue to be of major importance.[c] Bernard helped found 163 monasteries in different parts of Europe. Cistercians honour him as one of the greatest early Cistercians. His feast day is 20 August.

Bernard is Dante Alighieri's last guide, in Divine Comedy, as he travels through the Empyrean.[36]

John Calvin and Martin Luther quoted Bernard several times[37] in support of the doctrine of Sola Fide.[38][39] Calvin also quotes him in setting forth his doctrine of forensic alien righteousness, or as it is commonly called imputed righteousness.[40] Bernard introduced a major shift, a "fundamental reorientation" into medieval theology.[41]

The Couvent et Basilique Saint-Bernard, a collection of buildings dating from the 12th, 17th, and 19th centuries, is dedicated to Bernard and stands in his birthplace of Fontaine-lès-Dijon.[42] Countless churches and chapels have St. Bernard as their patron saint.

Works

[edit]

The modern critical edition is Sancti Bernardi opera (1957–1977), edited by Jean Leclercq.[43][d]

Bernard's works include:

- De gradibus humilitatis et superbiae [The steps of humility and pride] (in Latin). c. 1120.[44]

- Apologia ad Guillelmum Sancti Theoderici Abbatem [Apology to William of St. Thierry] (in Latin). Written in the defence of the Cistercians against the claims of the monks of Cluny.[45]

- De conversione ad clericos sermo seu liber [On the conversion of clerics] (in Latin). 1122.[46]

- De gratia et libero arbitrio [On grace and free choice] (in Latin). c. 1128..[47]

- De diligendo Dei [On loving God] (in Latin).[48]

- Liber ad milites templi de laude novae militiae [In Praise of the new knighthood] (in Latin). 1129.[49][50]

- De praecepto et dispensatione libri [Book of precepts and dispensations] (in Latin). c. 1144.[51]

- De consideratione [On consideration] (in Latin). c. 1150. Addressed to Pope Eugene III.[52]

- Liber De vita et rebus gestis Sancti Malachiae Hiberniae Episcopi [The life and death of Saint Malachy, bishop of Ireland] (in Latin).[53]

- De moribus et officio episcoporum (in Latin). A letter to Henri Sanglier, Archbishop of Sens on the duties of bishops.[54]

His sermons are also numerous:

- Most famous are his Sermones super Cantica Canticorum (Sermons on the Song of Songs). They may have found their origins in sermons preached to the monks of Clairvaux, but theories differ.[e] These sermons contain an autobiographical passage, sermon 26, mourning the death of his brother, Gerard.[55][56] After Bernard died, the English Cistercian Gilbert of Hoyland continued Bernard's incomplete series of 86 sermons on the biblical Song of Songs.

- There are 125 surviving Sermones per annum (Sermons on the Liturgical Year).

- There are also Sermones de diversis (Sermons on Different Topics).

- 547 letters survive.[57]

Misattributions

[edit]Numerous letters, treatises, and other works were falsely attributed to him.[7] These include:

- pseudo-Bernard (pseud. of Guigo I) (c. 1150). L'échelle du cloître [The scale of the cloister] (letter) (in French).[7]

- pseudo-Bernard. Meditatio [Meditations] (in Latin). This was probably written at some point in the thirteenth century. It circulated extensively in the Middle Ages under Bernard's name and was one of the most popular religious works of the later Middle Ages. Its theme is self-knowledge as the beginning of wisdom; it begins with the phrase "Many know much, but do not know themselves".[58][59][7]

- pseudo-Bernard. L'édification de la maison intérieure (in French).[7]

- The hymn Jesu dulcis memoria.[60]

- L’enfer est plein de bonnes volontés ou désirs [hell is full of good intentions and wills]. Francis de Sales, in a letter to Madame de Chantal in 1604.[61] No works have been found with this proverb.

Translations

[edit]- On consideration, translated by George Lewis, (Oxford, 1908) https://books.google.com/books?id=kkoJAQAAIAAJ

- Select treatises of S. Bernard of Clairvaux: De diligendo Deo & De gradibus humilitatis et superbiae, (Cambridge: CUP, 1926)

- On loving God, and selections from sermons, edited by Hugh Martin, (London: SCM Press, 1959) [reprinted as (Westport, CO: Greenwood Press, 1981)]

- Cistercians and Cluniacs: St. Bernard's Apologia to Abbot William, translated by Michael Casey. Cistercian Fathers series no. 1, (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1970)

- The works of Bernard of Clairvaux. Vol.1, Treatises, 1, edited by M. Basil Pennington. Cistercian Fathers Series, no. 1. (Spencer, Mass.: Cistercian Publications, 1970) [contains the treatises Apologia to Abbot William and On Precept and Dispensation, and two shorter liturgical treatises]

- Bernard of Clairvaux, On the Song of Songs, 4 vols, Cistercian Fathers series nos 4, 7, 31, 40, (Spencer, MA: Cistercian Publications, 1971–80)

- Letter of Saint Bernard of Clairvaux on revision of Cistercian chant = Epistola S[ancti] Bernardi de revisione cantus Cisterciensis, edited and translated by Francis J. Guentner, (American Institute of Musicology, 1974)

- Treatises II: The steps of humility and pride on loving God, Cistercian Fathers series no. 13 (Washington: Cistercian Publications, 1984)

- Five books on consideration: advice to a Pope, translated by John D. Anderson & Elizabeth T. Kennan. Cistercian Fathers Series no. 37. (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1976)

- The Works of Bernard of Clairvaux. Volume Seven, Treatises III: On Grace and free choice. In praise of the new knighthood, translated by Conrad Greenia. Cistercian Fathers Series no. 19, (Kalamazoo, Mich.: Cistercian Publications Inc., 1977)

- The life and death of Saint Malachy, the Irishman translated and annotated by Robert T. Meyer, (Kalamazoo, Mich.: Cistercian Publications, 1978)

- Bernard of Clairvaux, Homiliae in laudibus Virginis Matris, in Magnificat: homilies in praise of the Blessed Virgin Mary translated by Marie-Bernard Saïd and Grace Perigo, Cistercian Fathers Series no. 18, (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1979)

- Sermons on Conversion: on conversion, a sermon to clerics and Lenten sermons on the psalm "He Who Dwells", Cistercian Fathers Series no. 25, (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1981)

- Bernard of Clairvaux, Song of Solomon, translated by Samuel J. Eales, (Minneapolis, MN: Klock & Klock, 1984)

- St. Bernard's sermons on the Blessed Virgin Mary, translated from the original Latin by a priest of Mount Melleray, (Chumleigh: Augustine, 1984)

- Bernard of Clairvaux, The twelve steps of humility and pride; and, On loving God, edited by Halcyon C. Backhouse, (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1985)

- St. Bernard's sermons on the Nativity, translated from the original Latin by a priest of Mount Melleray, (Devon: Augustine, 1985)

- Bernard of Clairvaux : selected works, translation and foreword by G.R. Evans; introduction by Jean Leclercq; preface by Ewert H. Cousins (New York: Paulist Press, 1987) [contains the treatises On conversion, On the steps of humility and pride, On consideration, and On loving God; extracts from Sermons on The song of songs, and a selection of letters]

- Conrad Rudolph, The 'Things of Greater Importance': Bernard of Clairvaux's Apologia and the Medieval Attitude Toward Art, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990) [Includes the Apologia in both Leclercq's Latin text and English translation]

- Love without measure: extracts from the writings of St Bernard of Clairvaux, introduced and arranged by Paul Diemer, Cistercian studies series no. 127, (Kalamazoo, Mich. : Cistercian Publications, 1990)

- Sermons for the summer season: liturgical sermons from Rogationtide and Pentecost, translated by Beverly Mayne Kienzle; additional translations by James Jarzembowski, (Kalamazoo, Mich: Cistercian Publications, 1991)

- Bernard of Clairvaux, On loving God, Cistercian Fathers series no. 13B, (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1995)

- Bernard of Clairvaux, The parables & the sentences, edited by Maureen M. O'Brien. Cistercian Fathers Series no. 55, (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 2000)

- Bernard of Clairvaux, On baptism and the office of bishops, on the conduct and office of bishops, on baptism and other questions: two letter-treatises, translated by Pauline Matarasso. Cistercian Fathers Series no. 67, (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 2004)

- Bernard of Clairvaux, Sermons for Advent and the Christmas season translated by Irene Edmonds, Wendy Mary Beckett, Conrad Greenia; edited by John Leinenweber; introduction by Wim Verbaal. Cistercian Fathers Series no. 51, (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 2007)

- Bernard of Clairvaux, Sermons for Lent and the Easter Season, edited by John Leinenweber and Mark Scott, OCSO. Cistercian Fathers Series no. 52, (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 2013)

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ André de Montbard, one of the founders of the Knights Templar, was a half-brother of Bernard's mother.

- ^ Other mystics such as John of the Cross also found their language and symbols in Song of Songs.[22]

- ^ His texts are prescribed reading in Cistercian congregations.

- ^ For a research guide see McGuire (2013).

- ^ For a history of the debate over the Sermons, and an attempted solution, see Leclercq, Jean. Introduction. In Walsh (1976), pp. vii–xxx.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018. Church Publishing, Inc. 17 December 2019. ISBN 978-1-64065-235-4.

- ^ "Notable Lutheran Saints". resurrectionpeople.org. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ Schachenmayr, Alkuin (2020). "Conference Notes on Stephen Harding as the Sole Author of the Carta Caritatis: Did the Carta found the Order?". Cistercian Studies Quarterly. 55 (4): 417–424.

- ^ McManners 1990, p. 204.

- ^ Olson (2013). Bernard of Clairvaux, Saint. Defender of Christianity Against Rationalism. Taylor & Francis.

- ^ Mixa, Robert (20 August 2017). "St. Bernard of Clairvaux – Promoter of the Religious Life Par Excellence". Vocation Blog. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gildas 1907.

- ^ "Expositio in Apocalypsim". Cambridge Digital Library (manuscript). MS Mm.5.31. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ Berman, Constance Hoffman (2010). The Cistercian Evolution: The Invention of a Religious Order in Twelfth-Century Europe. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-8122-0079-9.

- ^ Chautard, Jean-Baptiste (1946). The Soul of the Apostolate. Trappist, Ky. p. 59.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Sullivan, Karen (15 March 2011), Chapter One. Bernard of Clairvaux: The Chimera of His Age, University of Chicago Press, pp. 30–52, doi:10.7208/9780226781662-003 (inactive 4 November 2024), ISBN 978-0-226-78166-2, retrieved 14 October 2024

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Voigts, Michael (Fall 2023). ""Exeat Sane ad Oculos Filiorum: The Holiness of Grief and Vulnerability in Sermon 26 of the Sermones super Cantica Canticorum of Bernard of Clairvaux,"". Wesleyan Theological Journal. 60: 75-91.

- ^ Van Engen, John (1986). "The "Crisis of Cenobitism" Reconsidered: Benedictine Monasticism in the Years 1050-1150". Speculum. 61 (2): 269–304. doi:10.2307/2854041. ISSN 0038-7134. JSTOR 2854041.

- ^ McGuire, Brian Patrick (1991). The difficult saint: Bernard of Clairvaux and his tradition. Cistercian studies series. Kalamazoo, Mich: Cistercian Publications. ISBN 978-0-87907-626-9.

- ^ Pius XII (24 May 1953). "Doctor Mellifluus". www.vatican.va. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ Robertson, Duncan (1987). "The Experience of Reading: Bernard of Clairvaux "Sermons on the Song of Songs", I". Religion & Literature. 19 (1): 1–20. ISSN 0888-3769. JSTOR 40059330.

- ^ Maunder, Chris (7 August 2019). The Oxford Handbook of Mary. Oxford University Press. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-19-879255-0.

- ^ Bynum, Caroline Walker (1977). "Jesus as Mother and Abbot as Mother: Some Themes in Twelfth-Century Cistercian Writing". The Harvard Theological Review. 70 (3/4): 257–284. doi:10.1017/S0017816000019933. ISSN 0017-8160. JSTOR 1509631.

- ^ Holdsworth, Christopher (22 November 2012), Birkedal Bruun, Mette (ed.), "Bernard of Clairvaux: his first and greatest miracle was himself", The Cambridge Companion to the Cistercian Order (1 ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 173–185, doi:10.1017/cco9780511735899.017, ISBN 978-1-107-00131-2, retrieved 30 October 2024

- ^ White, Hayden V. (1960). "The Gregorian Ideal and Saint Bernard of Clairvaux". Journal of the History of Ideas. 21 (3): 321–348. doi:10.2307/2708141. JSTOR 2708141.

- ^ "Pierleóni nell'Enciclopedia Treccani".

- ^ Cunningham & Egan 1996, p. 128.

- ^ Cristiani 1977.

- ^ a b c Evans 2000, pp. 115–123.

- ^ McManners 1990, p. 210.

- ^ Billy, Dennis (24 December 1995). "Preaching Conversion through the Beatitudes: Bernard of Clairvaux's Ad clericos de conversione". Christendom Media. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ Krahmer, Shawn M. (2000). "The Virile Bride of Bernard of Clairvaux". Church History. 69 (2): 304–327. doi:10.2307/3169582. ISSN 0009-6407. JSTOR 3169582.

- ^ a b Riley-Smith 1991, p. 48.

- ^ a b Durant 1950, p. 594.

- ^ a b Norwich 2012.

- ^ Durant, Will; Durant, Ariel (1935). The age of Faith; a history of medieval civilization (Christian, Islamic, and Judaic) from Constantine to Dante, A.D. 325-1300. The Story of Civilization. Simon and Schuster. p. 594.

- ^ Durant 1950, p. 391.

- ^ Christiansen, Eric (1997). The northern Crusades (2nd, new ed.). London, England: Penguin. p. 53. ISBN 0-14-026653-4. OCLC 38197435.

- ^ Beverly Kienzle (2001): Bernard of Clairvaux, the 1143/44 Sermons and the 1145 Preaching Mission: From the Domestic to the Lord’s Vineyard. In: Cistercians, Heresy and Crusade in Occitania, 1145–1229: Preaching in the Lord’s Vineyard. Boydell & Brewer, pp. 81-82.

- ^ Ratisbonne, Theodore (2023). The Life and Times of St. Bernard (published 1859). p. 465.

- ^ Paradiso, cantos XXXI–XXXIII

- ^ Lane 1999, p. 100.

- ^ Calvin 1960, bk.3 ch.2 §25, bk.3 ch.12 §3.

- ^ Luther 1930, p. 130.

- ^ Calvin 1960, bk.3 ch.11 §22, bk.3 ch.25 §2.

- ^ Sommerfeldt, John R. (2000). "Review of Bernard of Clairvaux by G. R. Evans". The Catholic Historical Review. 86 (4): 661–663. ISSN 0008-8080. JSTOR 25025831.

- ^ Base Mérimée: Couvent et Basilique Saint-Bernard, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- ^ SBOp.

- ^ PL, 182, cols. 939–972c.

- ^ PL, 182, cols. 893–918a.

- ^ PL, 182, cols. 833–856d.

- ^ PL, 182, cols. 999–1030a.

- ^ PL, 182, cols. 971–1000b.

- ^ PL, 182, cols. 917–940b.

- ^ Curtin, D. P. (June 2011). In Praise of the New Chivalry. Dalcassian Publishing Company. ISBN 9798868923982.

- ^ PL, 182, cols. 857–894c.

- ^ PL, 182, cols. 727–808a.

- ^ PL, 182, cols. 1073–1118a.

- ^ Ep. 42 (PL, 182, cols. 807–834a).

- ^ Verbaal 2004.

- ^ PL, 183, cols. 785–1198A.

- ^ SBOp, v. 7–8.

- ^ PL, 184, cols. 485–508.

- ^ Bestul 2012, p. 164.

- ^ Deeming, Helen (2014). "Music and Contemplation in the Twelfth-Century "Dulcis Jesu memoria"". Journal of the Royal Musical Association. 139 (1). 3. doi:10.1080/02690403.2014.886410. ISSN 0269-0403. JSTOR 43303357.

- ^ Lear, Henrietta Louisa Farrer, ed. (1871). Spiritual Letters of St. Francis de Sales. Rivington (London, Oxford, & Cambridge). p. 70. "Letter XII. To Madame de Chantal, on Temptations of the Will" (dated November 21, 1604).

Sources

[edit]- Anon. (2010). Holy Women, Holy Men: Celebrating the Saints. Church Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-0-89869-637-0.

- Alphandéry, Paul D. (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 298–299.

- Pierre Aubé: Saint Bernard de Clairvaux, Paris, éd. Fayard, 2003, 812 pages.

- Bernard of Clairvaux (1976). On the Song of Songs II. Cistercian Fathers series. Vol. 7. Translated by Walsh, Kilian. Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications. ISBN 9780879077075. OCLC 2621974.

- Bernard of Clairvaux (1998). The letters of St Bernard of Clairvaux. Cistercian Fathers series. Vol. 62. Translated by James, Bruno Scott. Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications. ISBN 9780879071622.

- Bernard of Clairvaux (1836). Mabillon, Jean (ed.). Opera omnia. Patrologia Latina (in Latin). Vol. 182–185. Paris: Jacques Paul Migne. 6 tomes in 4 volumes.

- Bernard of Clairvaux (1957–1977). Leclerq, Jean; Talbot, Charles H.; Rochais, Henri Marie (eds.). Sancti Bernardi Opera (in Latin). Vol. 8 volumes in 9. Rome: Éditions cisterciennes. OCLC 654190630.

- Bestul, Thomas H (2012). "Meditatio/Meditation". In Hollywood, Amy; Beckman, Patricia Z. (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Christian Mysticism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521863650.

- Botterill, Steven (1994). Dante and the Mystical Tradition: Bernard of Clairvaux in the Commedia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Calvin, John (1960). McNeill, John T. (ed.). Institutes of the Christian Religion. Vol. 1. Translated by Battles, Ford Lewis. Philadelphia: Westminster Press. OCLC 844778472.

- Cantor, Norman (1994). The Civilization of the Middle Ages. New York: HarperPerennial. ISBN 0-06-092553-1.

- Cristiani, Léon (1977). St. Bernard of Clairvaux, 1090–1153. Translated by M. Angeline Bouchard. St. Paul Editions. ISBN 978-0-8198-0463-1. OCLC 2874038.

- Cunningham, Lawrence S.; Egan, Keith J. (1996). "Meditation and contemplation". Christian spirituality: themes from the tradition. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-3660-5.

- Duffy, Eamon (1997). Saints and Sinners, a History of the Popes.

- Durant, Will (1950). The Story of Civilization. Vol. IV: The Age of Faith. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Gildas, Marie (1907). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Evans, Gillian R. (2000). Bernard of Clairvaux (Great Medieval Thinkers). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512525-8.

- Gilson, Etienne (1940). The mystical theology of St Bernard. London: Sheed & Ward.

- Kemp, E. W. (1945). "Pope Alexander III and the Canonization of Saints: The Alexander Prize Essay". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 27: 13–28. doi:10.2307/3678572. ISSN 0080-4401. JSTOR 3678572. S2CID 159681002.

- Lane, Anthony N. S. (1999). John Calvin: student of the church fathers. Edinburgh: T & T Clark. ISBN 9780567086945.

- Ludlow, James Meeker (1896). The Age of the Crusades. Ten epochs of church history. Vol. 6. New York: Christian Literature. OCLC 904364803.

- Luther, Martin (1930). D. Martin Luthers Werke: kritische Gesammtausgabe (in German and Latin). Vol. 40. Weimar: Herman Böhlau.

- McGuire, Brian Patrick (30 September 2013), "Bernard of Clairvaux", Oxford Bibliographies, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/OBO/9780195396584-0088

- McManners, John (1990). The Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822928-3.

- Most, William G. (1996). "Mary's Immaculate Conception". ewtn.com. Irondale, AL: Eternal Word Television Network. Archived from the original on 19 February 1998. Retrieved 23 February 2015. Adapted from Most, William G. (1994). Our Lady in doctrine and devotion. Alexandria, VA: Notre Dame Institute Press. OCLC 855913595.

- Norwich, John Julius (2012). The Popes: A History. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-09-956587-1.

- Phillips, Walter Alison (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 795–798.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1991). The Atlas of the Crusades. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-2186-4.

- Runciman, Steven (1987). The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100–1187. A History of the Crusades. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-34771-8.

- Smith, William (2010). Catholic Church Milestones: People and Events That Shaped the Institutional Church. Indianapolis: Left Coast. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-60844-821-0.

- Verbaal, Wim (2004). "Preaching the dead from their graves: Bernard of Clairvaux's Lament on his brother Gerard". In Donavin, Georgiana; Nederman, Cary; Utz, Richard (eds.). Speculum sermonis: interdisciplinary reflections on the medieval sermon. Disputatio. Vol. 1. Turnhout: Brepols. pp. 113–139. doi:10.1484/M.DISPUT-EB.3.1616. ISBN 9782503513393.

External links

[edit]- Works by Bernard of Clairvaux at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Bernard of Clairvaux at the Internet Archive

- Works by Bernard of Clairvaux at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- "St. Bernard, Abbot", Butler's Lives of the Saints

- Opera omnia Sancti Bernardi Claraevallensis his complete works, in Latin

- Audio on the life of St. Bernard of Clairvaux from waysideaudio.com

- Database with all known medieval representations of Bernard

- Saint Bernard of Clairvaux at the Christian Iconography web site.

- "Here Followeth the Life of St. Bernard, the Mellifluous Doctor" from the Caxton translation of the Golden Legend

- "Two Accounts of the Early Career of St. Bernard" by William of Thierry and Arnold of Bonneval

- Saint Bernard of Clairvaux Abbot, Doctor of the Church-1153 at EWTN Global Catholic Network

- Colonnade Statue St Peter's Square

- Lewis E 26 De consideratione (On Consideration) at OPenn

- MS 484/11 Super cantica canticorum at OPenn

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch