Book of hours

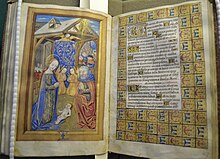

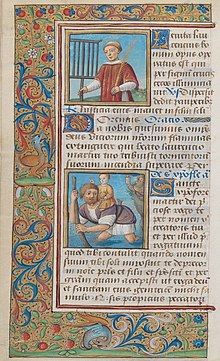

Books of hours (Latin: horae) are Christian prayer books, which were used to pray the canonical hours.[2] The use of a book of hours was especially popular in the Middle Ages, and as a result, they are the most common type of surviving medieval illuminated manuscript. Like every manuscript, each manuscript book of hours is unique in one way or another, but most contain a similar collection of texts, prayers and psalms, often with appropriate decorations, for Christian devotion. Illumination or decoration is minimal in many examples, often restricted to decorated capital letters at the start of psalms and other prayers, but books made for wealthy patrons may be extremely lavish, with full-page miniatures. These illustrations would combine picturesque scenes of country life with sacred images.[3]: 46

Books of hours were usually written in Latin (they were largely known by the name horae until "book of hours" was relatively recently applied to them), although there are many entirely or partially written in vernacular European languages, especially Dutch. The closely related primer is occasionally considered synonymous with books of hours – a medieval horae was referred to as a primer in Middle English[4] – but their contents and purposes could deviate significantly from the simple recitation of the canonical hours. Tens of thousands of books of hours have survived to the present day, in libraries and private collections throughout the world.

The typical book of hours is an abbreviated form of the breviary, which contains the Divine Office recited in monasteries. It was developed for lay people who wished to incorporate elements of monasticism into their devotional life. Reciting the hours typically centered upon the reading of a number of psalms and other prayers.

A typical book of hours contains the Calendar of Church feasts, extracts from the Four Gospels, the Mass readings for major feasts, the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the fifteen Psalms of Degrees, the seven Penitential Psalms, a Litany of Saints, an Office for the Dead and the Hours of the Cross.[5] Most 15th-century books of hours have these basic contents. The Marian prayers Obsecro te ("I beseech thee") and O Intemerata ("O undefiled one") were frequently added, as were devotions for use at Mass, and meditations on the Passion of Christ, among other optional texts. Such books of hours continue to be used by many Christians today, such as the Catholic “Key of Heaven” prayer books, the Agpeya of Coptic Christianity or The Brotherhood Prayer Book of Lutheranism.[6]

History

[edit]

The book of hours has its ultimate origin in the Psalter, which monks and nuns were required to recite. By the 12th century this had developed into the breviary, with weekly cycles of psalms, prayers, hymns, antiphons, and readings which changed with the liturgical season.[8] Eventually a selection of texts was produced in much shorter volumes and came to be called a book of hours.[9] During the latter part of the thirteenth century the Book of Hours became popular as a personal prayer book for men and women who led secular lives. It consisted of a selection of prayers, psalms, hymns and lessons based on the liturgy of the clergy. Each book was unique in its content though all included the Hours of the Virgin Mary, devotions to be made during the eight canonical hours of the day, the reasoning behind the name 'Book of Hours'.[10]

Many books of hours were made for women. There is some evidence that they were sometimes given as a wedding present from a husband to his bride.[9] Frequently they were passed down through the family, as recorded in wills.[9] Until about the 15th century paper was rare and most books of hours consisted of parchment sheets made from animal skins.

Although the most heavily illuminated books of hours were enormously expensive, a small book with little or no illumination was affordable much more widely,[7] and increasingly so during the 15th century. The earliest surviving English example was apparently written for a laywoman living in or near Oxford in about 1240. It is smaller than a modern paperback but heavily illuminated with major initials, but no full-page miniatures. By the 15th century, there are also examples of servants owning their own Books of Hours. In a court case from 1500, a pauper woman is accused of stealing a domestic servant's prayerbook.[citation needed]

Very rarely the books included prayers specifically composed for their owners, but more often the texts are adapted to their tastes or gender, including the inclusion of their names in prayers. Some include images depicting their owners, and some their coats of arms. These, together with the choice of saints commemorated in the calendar and suffrages, are the main clues for the identity of the first owner. Eamon Duffy explains how these books reflected the person who commissioned them. He claims that the "personal character of these books was often signaled by the inclusion of prayers specially composed or adapted for their owners." Furthermore, he states that "as many as half the surviving manuscript Books of Hours have annotations, marginalia or additions of some sort. Such additions might amount to no more than the insertion of some regional or personal patron saint in the standardized calendar, but they often include devotional material added by the owner. Owners could write in specific dates important to them, notes on the months where things happened that they wished to remember, and even the images found within these books would be personalized to the owners—such as localized saints and local festivities.[8]

By at least the 15th century, the Netherlands and Paris workshops were producing books of hours for stock or distribution, rather than waiting for individual commissions. These were sometimes with spaces left for the addition of personalized elements such as local feasts or heraldry.

The style and layout for traditional books of hours became increasingly standardized around the middle of the thirteenth century. The new style can be seen in the books produced by the Oxford illuminator William de Brailes who ran a commercial workshop (he was in minor orders). His books included various aspects of the Church's breviary and other liturgical aspects for use by the laity. "He incorporated a perpetual calendar, Gospels, prayers to the Virgin Mary, the Stations of the Cross, prayers to the Holy Spirit, Penitential psalms, litanies, prayers for the dead, and suffrages to the Saints. The book's goal was to help his devout patroness to structure her daily spiritual life in accordance with the eight canonical hours, Matins to Compline, observed by all devout members of the Church. The text, augmented by rubrication, gilding, miniatures, and beautiful illuminations, sought to inspire meditation on the mysteries of faith, the sacrifice made by Christ for man, and the horrors of hell, and to especially highlight devotion to the Virgin Mary whose popularity was at a zenith during the 13th century."[11] This arrangement was maintained over the years as many aristocrats commissioned the production of their own books.

By the end of the 15th century, the advent of printing made books more affordable and much of the emerging middle-class could afford to buy a printed book of hours, and new manuscripts were only commissioned by the very wealthy. The Kitab salat al-sawai (1514), widely considered the first book in Arabic printed using moveable type, is a book of hours intended for Arabic-speaking Christians and presumably commissioned by Pope Julius II.[12]

Decoration

[edit]

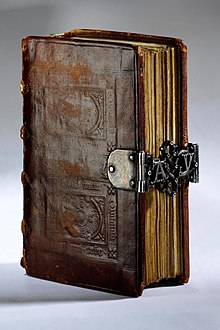

As many books of hours are richly illuminated, they form an important record of life in the 15th and 16th centuries as well as the iconography of medieval Christianity. Some of them were also decorated with jewelled covers, portraits, and heraldic emblems. Some were bound as girdle books for easy carrying, though few of these or other medieval bindings have survived. Luxury books, like the Talbot Hours of John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury, may include a portrait of the owner, and in this case his wife, kneeling in adoration of the Virgin and Child as a form of donor portrait. In expensive books, miniature cycles showed the Life of the Virgin or the Passion of Christ in eight scenes decorating the eight Hours of the Virgin, and the Labours of the Months and signs of the zodiac decorating the calendar. Secular scenes of calendar cycles include many of the best known images from books of hours, and played an important role in the early history of landscape painting.

From the 14th century decorated borders round the edges of at least important pages were common in heavily illuminated books, including books of hours. At the beginning of the 15th century these were still usually based on foliage designs, and painted on a plain background, but by the second half of the century coloured or patterned backgrounds with images of all sorts of objects, were used in luxury books.

Second-hand books of hours were often modified for new owners, even among royalty. After defeating Richard III, Henry VII gave Richard's book of hours to his mother, who modified it to include her name. Heraldry was usually erased or over-painted by new owners. Many have handwritten annotations, personal additions and marginal notes but some new owners also commissioned new craftsmen to include more illustrations or texts. Sir Thomas Lewkenor of Trotton hired an illustrator to add details to what is now known as the Lewkenor Hours. Flyleaves of some surviving books include notes of household accounting or records of births and deaths, in the manner of later family bibles. Some owners had also collected autographs of notable visitors to their house. Books of hours were often the only book in a house, and were commonly used to teach children to read, sometimes having a page with the alphabet to assist this.

Towards the end of the 15th century, printers produced books of hours with woodcut illustrations, and the book of hours was one of the main works decorated in the related metalcut technique.

The luxury book of hours

[edit]

(Among the plants are the Veronica, Vinca, Viola tricolor, Bellis perennis, and Chelidonium majus. The lower butterfly is Aglais urticae, the top left butterfly is Pieris rapae. The Latin text is a devotion to Saint Christopher).

In the 14th century the book of hours overtook the psalter as the most common vehicle for lavish illumination. This partly reflected the increasing dominance of illumination both commissioned and executed by laymen rather than monastic clergy. From the late 14th century a number of bibliophile royal figures began to collect luxury illuminated manuscripts for their decorations, a fashion that spread across Europe from the Valois courts of France and the Burgundy, as well as Prague under Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor and later Wenceslaus. A generation later, Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy was the most important collector of manuscripts, with several of his circle also collecting.[13]: 8–9 It was during this period that the Flemish cities overtook Paris as the leading force in illumination, a position they retained until the terminal decline of the illuminated manuscript in the early 16th century.

The most famous collector of all, the French prince John, Duke of Berry (1340–1416) owned several books of hours, some of which survive, including the most celebrated of all, the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. This was begun around 1410 by the Limbourg brothers, although left incomplete by them, and decoration continued over several decades by other artists and owners. The same was true of the Turin-Milan Hours, which also passed through Berry's ownership.

By the mid-15th century, a much wider group of nobility and rich businesspeople were able to commission highly decorated, often small, books of hours. With the arrival of printing, the market contracted sharply, and by 1500 the finest quality books were once again being produced only for royal or very grand collectors. One of the last major illuminated book of hours was the Farnese Hours completed for the Roman Cardinal Alessandro Farnese in 1546 by Giulio Clovio, who was also the last major manuscript illuminator.

Gallery

[edit]- The Visconti Hours

- Calendar page from the Hours of Catherine of Cleves for June 1–15.

- Book of Hours of Jeanne d'Evreux: Arrest of Jesus and Annunciation

- Book of hours of Simone de Varie, portrait of the owner and his wife

- Book of Hours, British Library, the Arrest of Christ

- Scenes from the Life of Christ and Life of the Virgin in the same book

- Les Très Riches Heures

du duc de Berry

A Funeral Service - Bedford Hours; building the Tower of Babel

- The Visitation, 1440–45

- Printed Bulgarian book of hours, 1566

- Llanbeblig Hours. St. Peter, holding a key and a book

- French thumb-sized miniature prayer book from the collection of National Library of Poland

Selected examples

[edit]

See Category:Illuminated books of hours for a fuller list

In Europe

[edit]- Bedford Hours (c.1410–1430): London, British Library, Add. MS 18850

- Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry (c.1405–1408/1409): Metropolitan Museum of Art, Cloisters Collection, 54.1.1a, b

- Black Hours of Galeazzo Maria Sforza (c.1466–1477): Vienna, Austrian National Library, Codex Vindobon. 1856

- Book of Hours (15th century): Milan, Biblioteca Trivulziana, Cod. 470

- Book of Hours (15th century): Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, MS lat. 10536 — one of the few early cordiform manuscripts still extant

- Book of Hours of Frederick of Aragon (1501–1502): Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, MS Lat. 10532

- Cobden Book of Hours: Bristol University Special Collections

- Grandes Heures of Anne of Brittany (1503–1508): Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, MS lat. 9474

- Hours of Étienne Chevalier (1450s) — sheets in several libraries

- Hours of Gian Galeazzo Visconti (late 14th century): Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale, Banco Rari 397 and Landau-Finaly 22

- Hours of James IV of Scotland (c.1503): Austrian National Library, Codex Vindobon. 1897

- Hours of Philip the Bold (late 14th century): Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 3-1954

- Howard Psalter and Hours (1310–1320): London, British Library, Arundel MS 83, pt 1

- Llanbeblig Book of Hours (1390–1400): Aberystwyth, National Library of Wales, NLW MS 17520A

- Petites Heures du Duc de Berry (1375×1385–1390): Paris, Royal Library, MS lat. 18014

- Primer of Claude of France (1505): Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 294 — simplified for a young princess

- Ravenelle Hours (15th century): Uppsala, UUB, MS C517e — a typical representative of books of hours made in Paris

- Rohan Hours (1430s): Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, MS lat. 9471

- Sforza Hours (commissioned c.1490, completed c.1517–1520): London, British Library, Add. MS 34294

- Taymouth Hours (c.1325–1335): London, British Library, Yates Thompson MS 13

- Très belles heures du Duc de Berry: Brussels, Royal Library of Belgium, 11060–11061

- Très belles heures de Notre-Dame du Duc de Berry: Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, nouv. acq. lat. 3093

- Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (c.1411–1416): Chantilly, Musée Condé, MS 65

- Turin-Milan Hours: Turin, City Museum of Ancient Art, MS Inv. 47

- 'The De Brailes Hours', formerly known as 'The Dyson Perrins Hours' (1240): London, British Library, Add. MS 49999

In the United States

[edit]- Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry (c.1405–1408/9): New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters, 54.1.1a, b — miniatures of 'the Limburg Brothers'

- Black Hours (1460–1475): New York, Morgan Library, Morgan MS 493 — an example of Black Hours, codices copied on black pages

- Farnese Hours (1546): New York, Morgan Library, MS M.69 — illuminated by Giulio Clovio

- Hours of Catherine of Cleves, property of 'Katharina van Kleef' (15th century): New York, Morgan Library, MSS M.917 and M.945

- Hours of Henry VIII: New York, Morgan Library, MS H.8 — with miniatures by Jean Poyer

- Hours of Jeanne d'Evreux (1325–1328): New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters, 54.1.2

In Australia

[edit]- Rothschild Prayerbook (c.1500–1520): on display at the National Library of Australia in Canberra, owned by Australian businessman Kerry Stokes.

See also

[edit]- Agpeya

- Black books of hours

- Divine Service (Eastern Orthodoxy) and Horologion

- Grey-FitzPayn Hours

- Hours of Angers

- Hours of Charles V

- Hours of John the Fearless

- Hours of Peter II

- Liturgy of the Hours

References

[edit]- ^ Plummer, John (1966). The Hours of Catherine of Cleves. New York: George Braziller. pp. plates 1–2.

- ^ Pearsall, Derek (11 June 2014). Gothic Europe 1200-1450. Routledge. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-317-88952-6.

The book of hours was the favourite prayer-book of lay-people, and enabled them to follow, in private, the church's programme of daily devotion at the seven canonical hours.

- ^ Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books: A Living History. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. ISBN 978-1-60606-083-4.

- ^ Scott-Stokes, Charity (2006). Women's Books of Hours in Medieval England: Selected Texts Translated from Latin, Anglo-Norman French and Middle English with Introduction and Interpretative Essay. Library of Medieval Women. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. p. 1.

- ^ Hore de Cruce, Danish Royal Library. Archived December 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Lutheran Liturgical Prayer Brotherhood". Evangelisch-Lutherische Gebetsbruderschaft. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

In short, the Brotherhood Prayer Book is a fully catholic book of hours refracted through the lens of the Lutheran confessions.

- ^ a b "Middelnederlands getijdenboek" [Middle Netherlands Book of hours (lit. 'Tides book')]. lib.ugent.be. Retrieved 2020-08-27.

- ^ a b Duffy, Eamon (Nov 2006). "A Very Personal Possession: Eamon Duffy Tells How a Careful Study of Surviving Books of Hours Can Tell Us Much About the Spiritual and Temporal Life of Their Owners and Much More Besides". History Today. Vol. 56, no. 11. pp. 12(7).

- ^ a b c Harthan, John (1977). The Book of Hours: With a Historical Survey and Commentary by John Harthan. New York: Crowell.

- ^ Hirst, Warwick (2003). "The Fine Art of Illumination". Heritage Collection, Nelson Meers Foundation, 2003 (PDF). Sydney: State Library of New South Wales. pp. 8–9. Retrieved 17 Feb 2022.

- ^ Webb, M.; Albers, M. J. (2001). "The Design Elements of Medieval Books of Hours". Journal of Technical Writing and Communication. 31 (4): 353–361 [354]. doi:10.2190/1BLL-2DA9-D52X-TU4J. S2CID 108454672.

- ^ Krek, M. (1979). "The Enigma of the First Arabic Book Printed from Movable Type". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 38 (3): 203–212. doi:10.1086/372742. S2CID 162374182.

- ^ Thomas, Marcel (1979). The Golden Age; Manuscript Painting at the Time of Jean, Duc de Berry. Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0701124725.

- ^ "Getijdenboek van Alexandre Petau" [Book of hours of Alexandre Petau]. lib.ugent.be. Retrieved 2020-08-27.

Further reading

[edit]- Ashley, K.M. (2002) Creating Family Identity in Books of Hours. Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, (1) 145–165.

- Calkins, Robert G. Illuminated Books of the Middle Ages. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1983. ISBN 9780801415067

- Dückers, Rob, and Pieter Roelofs. The Limbourg Brothers - Nijmegen Masters at the French Court 1400-1416. Ghent: Ludion, 2005. ISBN 9789055445776

- Duffy, Eamon. Marking the Hours: English People and their Prayers 1240 - 1570. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-300-11714-0

- Duffy, Eamon, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580 (Yale, 1992) ISBN 0-300-06076-9

- The Oxford Dictionary of Art ISBN 0-19-280022-1

- Pächt, Otto. Book Illumination in the Middle Ages (translation, Kay Davenport), London: Harvey Miller Publishers, 1986. ISBN 0-19-921060-8

- Simmons, Eleanor. Les Heures de Nuremberg, Les Editions du Cerf, Paris, 1994. ISBN 2-204-04841-0

- Wieck, Roger S. Painted Prayers: The Book of Hours in Medieval and Renaissance Art, New York: George Braziller, 2004. ISBN 978-0-8076-1457-0

- Wieck, Roger S. Time Sanctified: The Book of Hours in Medieval Art and Life, New York: George Braziller, 1988. ISBN 978-0807614983

For individual works

[edit]- The Hours of Mary of Burgundy (facsimile edition). Harvey Miller, 1995. ISBN 1-872501-87-7

- Barstow, Kurt. The Gualenghi-d'Este Hours: Art and Devotion in Renaissance Ferrara. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2000. ISBN 978-0-89236-370-4

- Clark, Gregory T. The Spitz Master: A Parisian Book of Hours. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2003. ISBN 9780892367122

- Meiss, Millard, and Edith W. Kirsch. The Visconti Hours. New York: George Braziller, 1972. ISBN 9780807613597

- Meiss, Millard, and Elizabeth H. Beatson. The Belles Heures of Jean, Duke of Berry. New York: George Braziller, 1974. ISBN 978-0807607503

- Meiss, Millard, and Marcel Thomas. The Rohan Master: A Book of Hours (translation, Katharine W. Carson). New York: George Braziller, 1973. ISBN 978-0807613580

- Porcher, Jean. The Rohan Book of Hours: With an Introduction and Notes by Jean Porcher. New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1959.

- Manion, Margaret and Vines, Vera. Medieval and Renaissance Illuminated Manuscripts in Australian Collections, 1984. IE9737078

External links

[edit]General information

[edit]- Book of Hours - Harry Ransom Center of the University of Texas at Austin

- World Digital Library from partner - Library of Congress (Digital Books of Hours)

- "A Masterpiece Reconstructed: The Hours of Louis XII". Prints & Books. Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 2011-02-02. Retrieved 2009-11-28.

- Sacred Image and Illusion in Late Flemish Manuscripts, Robert G. Calkins, Cornell University

- AbeBooks, Explaining Books of Hours with a varied selection of examples.

- 541 examples from the Digital Scriptorium

- Book of Hours Tutorial, Les Enluminures and the Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.1093

- Blog: PECIA/ Le manuscrit médiéval ~ The medieval manuscript Archived 2011-04-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Prints & People: A Social History of Printed Pictures, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF)

- CHD Center for Håndskriftstudier i Danmark, founded by Erik Drigsdahl

Full "turn the pages" online individual manuscripts

[edit]- Lavishly illustrated Books of Hours, 12th through 16th centuries, Center for Digital Initiatives, University of Vermont Libraries

- The Sforza Hours at the British Library.

- Book of Hours, Use of Rome (the 'Golf Book'), c.1540, BL, Add MS 24098.

- Catholic Church. Book of hours Ms.Library of Congress. Rosenwald ms. 10, 1524. 113 leaves (23 lines (calendar 33 lines)), bound: parchment, col. ill.; 24 cm.

- Picturing Prayer, Books of Hours at Houghton Library, Harvard University.

- Book of Hours, of Premonstratensian Use at the Digital Archives Initiative Memorial University of Newfoundland.

- Late 15th Century French Book of Hours- De Villers Book of Hours, Digitized Collection: Utah State University.

- Book of Hours, circa 1430: University of Edinburgh MS 39.

- Book of Hours from the Netherlands, Trinity College Dublin Library MS 103.

- Book of Hours, Paris (15th century), Trinity College Dublin Library MS 104.

The texts

[edit]- A Hypertext Book of Hours; full texts and translation

- Late Medieval and Renaissance Illuminated Manuscripts - Books of Hours 1400-1530 - An excellent guide containing tables describing all the various uses; also with original Latin texts and high-resolution photographs of many books.

- Books of Hours at the University of Pennsylvania Libraries - fully digitized with descriptions.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch