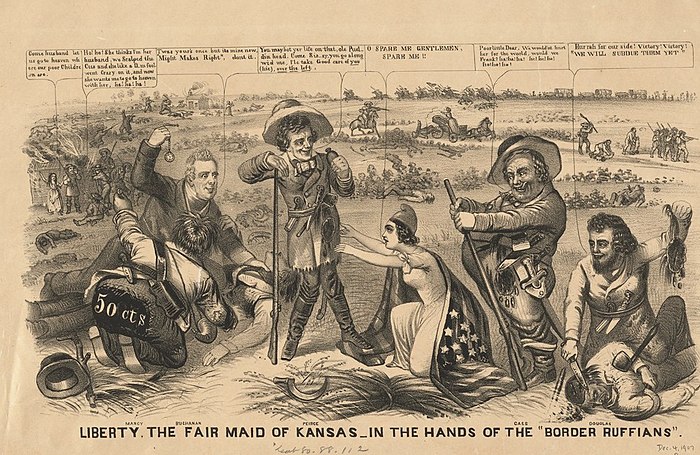

Border ruffian

Border ruffians were proslavery raiders who crossed into the Kansas Territory from Missouri during the mid-19th century to help ensure the territory entered the United States as a slave state. Their activities formed a major part of a series of violent civil confrontations known as "Bleeding Kansas", which peaked from 1854 to 1858. Crimes committed by border ruffians included electoral fraud, intimidation, assault, property damage and murder; many border ruffians took pride in their reputation as criminals. After the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, many border ruffians fought on the side of the Confederate States of America as irregular bushwhackers.

Origin

[edit]

The 1913 edition of Webster's Dictionary reflects the 19th century understanding of the word ruffian as a "scoundrel, rascal, or unprincipled, deceitful, brutal and unreliable person".

Among the first to use the term border ruffian in connection with the slavery issue in Kansas was the Herald of Freedom, a newspaper published in Lawrence, Kansas. On October 8, 1857, it reported the following:

Gov. Reeder soon after March 30 visited Washington, hoping to induce Pres. Pierce to disregard the election. On his way there he stopped at his old home, Easton, Pa., and told the story of Kansas' wrongs, in a speech to his old neighbors. In this he designated the invaders as "Border Ruffians", and said they were led by their chiefs, David R. Atchison and B. F. Stringfellow.[1]

Armed with revolvers and Bowie knives, border ruffians forcefully interfered in the Kansas row over slavery.[2][3] A correspondent for the London Times while visiting Kansas in 1856 reported many occurrences of the so-called bowie-knife voting in Kansas when voters were heckled and harassed by border ruffians.[4] In response, the New England Emigrant Aid Company shipped Sharps rifles to the Kansas Territory, in crates said to have been labeled "Bibles".[5][6]

At that time, many Kansas settlers opposed slavery. However, slavery advocates were determined to have their way regardless. When elections were held, bands of armed border ruffians seized polling places, prevented Free-State men from voting, and cast votes illegally, falsely stating they were Kansas residents.[7][8]

Border ruffians operated from Missouri. It was said that they voted and shot in Kansas, but slept in Missouri.[9] They not only interfered in territorial elections, but also committed outrages on Free-State settlers and destroyed their property. This violence gave the origin of the phrase "Bleeding Kansas". However, political killings and violence were exercised by both warring sides.[10][11][12]

The federal government did not interfere to stop the violence.[13] Hence, such ignominious episodes as the sacking of Lawrence, Kansas, in May 1856 became possible. U.S. Senator David Rice Atchison (D-Missouri) personally incited the assembling mob:

Gentlemen, Officers & Soldiers! This is the most glorious day of my life! This is the day I am a border ruffian! ... Spring like your bloodhounds at home upon that d--d accursed abolition hole; break through every thing that may oppose your never flinching courage! Yess, ruffians, draw your revolvers & bowie knives, & cool them in the heart's blood of all those d--d dogs, that dare defend that d--d breathing hole of hell.[14][15]

Border ruffians contributed to the increasingly violent sectional tensions, culminating in the American Civil War.[16]

Leaders and followers

[edit]Border ruffians did not constitute an organized group. They never had meetings, had no designated leaders, and no one ever directed any message to them as a body.

Border ruffians were driven by the rhetoric of politicians such as David Rice Atchison, Benjamin Franklin Stringfellow, John H. Stringfellow, editor of the pro-slavery newspaper Squatter Sovereign (Atchison, Kansas), and Speaker of the House in the First Kansas Territorial Legislature, the so-called Bogus Legislature.[17] and Rev. Thomas Johnson, a Methodist preacher.[18] Samuel J. Jones, and Daniel Woodson, a proslavery newspaper editor.[19][20][page needed] In particular, Atchison called Northerners "negro thieves" and "abolitionist tyrants". He encouraged Missourians to defend their institution "with the bayonet and with blood" and, if necessary, "to kill every God-damned abolitionist in the district".[21]

Few of the ordinary border ruffians actually owned slaves because most were too poor. Their motivation was hatred of Yankees and abolitionists, and fear of free Blacks living nearby. Kansas slavery was small-scale and operated mainly at the household level.[22] Most of the Kansans, according to historian David M. Potter, were concerned primarily about land titles. He pointed out that, "the great anomaly of 'Bleeding Kansas' is that the slavery issue reached a condition of intolerable tension and violence ... in an area where a majority of the inhabitants apparently did not care very much one way or the other about slavery."[23]

Frank W. Blackmar's encyclopedia of Kansas history summarizes how the rank-and-file among border ruffians took pride in both how they were called and what they were doing:

While the main objects of the Border Ruffian chiefs were the overthrow and destruction of free-state men and the establishment of slavery in Kansas, the ruffian border bands delighted in raiding towns, ransacking houses, stealing horses, and doing whatever they could that was annoying, exciting, and rough. The towns and country along the eastern tier of counties were raided with uncomfortable frequency. Free-state men holding claims were driven from them, elections were molested and crimes of violence committed. When the crash came between north and south many of these men became bushwhackers or guerrillas.[24]

The presence of violent bands of both Kansan and Missourian combatants made it difficult for settlers on the Kansas–Missouri border to remain neutral.[7]

History

[edit]The history of border ruffians is woven into the historical context of Bleeding Kansas, or the border war, a series of violent civil confrontations in Kansas in 1854–1859.[25] Kansas Territory was created by the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854. The Act repealed the previous Federal prohibition on slavery in that area. Instead, the locally elected territorial legislature was to decide on the slavery issue.[7]

The first territorial census, taken in January–February 1855, counted 8601 people; 2905 were deemed eligible to vote; there were 192 enslaved in the Territory.[26][page needed][27]

After the Kansas–Nebraska Act repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and allowed Kansans to vote on slavery, the opponents from both sides of the slavery debate started to recruit settlers to increase support of their causes.

Immigration to Kansas

[edit]Proslavery immigrants aided by the Lafayette Emigration Society, and anti-slavery settlers, established their own territorial enclave (such as Atchison and Leavenworth), and Free-State immigrants aided by the New England Emigrant Aid Company established theirs (such as Lawrence, Topeka).[28][29][30] This circumstance resulted in a deep partisan divide in regard to the slavery question among settlers and their civic and business leaders. Then extremists on both side resorted to arms. On the pro-slavery side violence was committed by the border ruffians and on the free-state side by the jayhawkers.[24][31][32][33]

On November 29, 1854, border ruffians elected a pro-slavery territorial representative to Congress, John W. Whitfield. It was determined after a Congressional investigation that 60% of the votes were illegal.[23]

On March 30, 1855, border ruffians elected a pro-slavery Territorial Legislature, which introduced harsh penalties for speaking against slavery.[34] It was called the Bogus Legislature by Free-Staters due to the fact that border ruffians arrived en masse and there were twice as many votes cast than there were eligible voters in the Territory. Failure to ensure fair elections led to establishment of two territorial governments in Kansas, one pro-slavery and another Free State, each claiming to be the only legitimate government of the entire Territory.[23]

Despite all border ruffians' attempts to push anti-slavery settlers out of the Territory, far more Free-State immigrants moved to Kansas than pro-slavery.[citation needed] In 1857, the pro-slavery faction in Kansas proposed the Lecompton Constitution for the future state of Kansas. It tried to get the Lecompton Constitution adopted with additional fraud and violence, but by then there were too many Free-Staters there and the U.S. Congress refused to confirm it.[8]

Border ruffians also engaged in general violence against Free-State settlements. They burned farms and sometimes murdered Free-State men. Most notoriously, border ruffians twice attacked Lawrence, the Free-State capital of the Kansas Territory. On December 1, 1855, a small army of border ruffians laid siege to Lawrence, but were driven off. This became the nearly bloodless climax to the "Wakarusa War".

On May 21, 1856, an even larger force of border ruffians and pro-slavery Kansans captured Lawrence, which they sacked.[7]

Free-State settlers struck back. Anti-slavery Kansan irregulars, led by Charles R. Jennison, James Montgomery, and James H. Lane, among others, and known as jayhawkers, attacked proslavery settlers and suspected border ruffian sympathizers.[35] Most notoriously, abolitionist John Brown killed five proslavery men at Pottawatomie.[7][36] In revenge, a band of border ruffians, led by John W. Reid, sacked the village of Osawatomie, Kansas after the Battle of Osawatomie.[37]

Aid to the Free-State cause

[edit]T. W. Higginson, a minister, was instrumental in turning the Massachusetts State Kansas Committee, a former subsidiary of the New England Emigrant Aid Company, into a nationally known organization.[38] It worked to recruit abolitionist settlers, raised funds for them to migrate to Kansas, and equipped them with rifles to use against border ruffians.[39] In 1856 it acquired 200 Sharps rifles for $4,947.88 that were shipped to Kansas via Iowa and ended in John Brown's hands.[40] In September 1858, it invested $3,800 in 190 Sharps rifles for Kansas.[41] Abolitionist Henry W. Beecher pronounced that,

Sharps rifle was a truly moral agency, and that there was more moral power in one of those instruments, so far as the slaveholders of Kansas were concerned, than in a hundred Bibles. You might just as well ... read the Bible to Buffaloes as those fellows who follow Atchison and Stringfellow; but they have a supreme respect for the logic that is embodied in Sharps rifles.[40]

It was documented that in 1855–1856 various aid organizations from free states spent at least $43,074.26 on rifles, muskets, revolvers, and ammunition, including one cannon, destined for Kansas.[40]

On July 9, 1856, the Massachusetts State Kansas Committee and the New England Emigrant Aid Company initiated the establishment of the Kansas National Aid Committee headquartered in Chicago. Thaddeus Hyatt, head of the national committee, began collecting money, arms, provisions, clothing, and agricultural supplies to aid the Free-State cause in Kansas. The goal was to transport five thousand settlers to Kansas Territory giving them a year's worth of supplies.[42]

A distribution depot was set up at Mt. Pleasant, Iowa, where immigrants were furnished not only with horses and wagons and other supplies, but also with arms; they were organized into companies and drilled. The National Kansas Committee spent in 1856–1857 around US$100,000 (equivalent to $3,390,000 in 2023) on the Free State cause.[40][43]

Outcomes

[edit]On August 2, 1858, the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution of 1857 was rejected at the polls, signifying the defeat of border ruffians' cause.[44] On January 29, 1861, President James Buchanan signed the bill that approved the Wyandotte Constitution and Kansas came to the Union as a Free State.[45]

During the Civil War

[edit]During the American Civil War, the violence on the Kansas-Missouri border not only continued, but escalated tremendously. Many of the former border ruffians became pro-Confederate guerrillas, or bushwhackers. They operated in western Missouri, sometimes raiding into Kansas, and Union forces campaigned to suppress them. Farms on the Missouri-Kansas state line were looted and burned. Suspected guerrillas were killed; in retaliation, bushwhackers murdered Union sympathizers and suspected informers. Confederate guerrilla leaders, such as "Bloody Bill" Anderson and William Quantrill, were feared in Kansas during the war.[46]

Many of the Union troops fighting bushwackers were former jayhawkers who held deep grudges against border ruffians. Charles R. Jennison recruited the 7th Kansas Cavalry Regiment, which became known as the Jennison's Jayhawkers. In the fall and winter of 1861 and 1862, Jennison's Jayhawkers became infamous for looting and destroying the property of Missourians.[47]

Some of the jayhawkers joined a paramilitary group called the Red Legs. Wearing red gaiters and numbered around 100, Red Legs served as scouts during the punitive expedition of the Union troops in Missouri. Jayhawkers and Red Legs pillaged and burned multiple towns in 1861–1863 in Missouri.[further explanation needed][48][49] The destruction of Osceola, Missouri, is depicted in the movie The Outlaw Josey Wales.[50]

See also

[edit]- Sacking of Lawrence

- Wakarusa War

- Pottawatomie massacre

- Battle of Osawatomie

- Marais des Cygnes massacre

References

[edit]- ^ Clark, Charles, Benjamin F. Stringfellow, kansasboguslegislature.org, archived from the original on April 11, 2022, retrieved March 11, 2021

- ^ Phillips, Jason (2018), Bowie Knives, Concealed Rifles, and Caning Charles Sumner, Adapted from The Looming Civil War: How Nineteenth-Century Americans Imagined the Future, Oxford University Press, archived from the original on February 28, 2021, retrieved March 11, 2021

- ^ Cecil-Fronsman, Bill. 'Death to All Yankees and Traitors in Kansas': The Squatter Sovereign and the Defense of Slavery in Kansas, Kansas History 16 (Spring 1993): 22–33.

- ^ Phillips, Jason (2018), Looming Civil War: How Nineteenth-Century Americans Imagined the Future, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 29, ISBN 978-0-19-086817-8, archived from the original on May 14, 2022, retrieved March 11, 2021

- ^ Sharps Carbine, National Museum of American History, archived from the original on May 14, 2022, retrieved March 16, 2021

- ^ Prichard, Jeremy. Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1855–1865. New England Emigrant Aid Company. Archived from the original on December 4, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Newlon, Jack, Rob Spooner, and Alicia Spooner. Bleeding Kansas: Mid 1850s – Precursor to the Civil War Archived June 30, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, in U-S-History.com. Online Highways, 2021

- ^ a b "Bleeding Kansas". Fort Scott National Historic Site. paragraph 1. Archived from the original on June 21, 2008. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ Hougen, Harvey R. (Summer 1985). "The Marais des Cygnes Massacre and the Execution of William Griffith". Kansas History. 8 (2): 76. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ Documented political killings in Bleeding Kansas, Kansas Historical Society, archived from the original on January 16, 2021, retrieved March 13, 2021

- ^ Watts, Dale. How Bloody was Bleeding Kansas? Political Killings in Kansas Territory, 1854–1861, Kansas History, Vol. 18, Summer 1995, pp. 116–129

- ^ Welch, G. Murlin. Border Warfare in Southeastern Kansas, 1856–1859. Pleasanton, Kans.: Linn County Publishers, 1977.

- ^ Ewy, Marvin (Winter 1966). "The United States Army in the Kansas Border Troubles, 1855–1856". Kansas Historical Quarterly. 32: 385–400.

- ^ Territorial Kansas Online – Transcripts Archived May 14, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, Kansas State Historical Society

- ^ Copy of David R. Atchison speech to proslavery forces Archived November 1, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Kansas State Historical Society

- ^ Monaghan, Jay. Civil War on the Western Border. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1955.[ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^ "Kansas Bogus Legislature: J. H. Stringfellow, Speaker of the House". Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ Pious Preacher or Radical Hypocrite? The Reverend Thomas Johnson Archived November 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, The New Santa Fe Trailer

- ^ Matthew E. Stanley. Woodson, Daniel Archived October 10, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1855–1865

- ^ Etcheson, Nicole. Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004.

- ^ Atchison, David R. (May 21, 1856). "Copy of David R. Atchison speech to proslavery forces". www.kansasmemory.org. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ Cory, Charles Easterbrook. Slavery in Kansas, Kansas Historical Collection 7 (1901–1902): 229–242.

- ^ a b c "Bleeding Kansas" Archived March 16, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, The E Pluribus Unum Project: America in the 1770s, 1850s, and 1920s, Assumption University

- ^ a b Kansas: A cyclopedia of state history, embracing events, institutions, industries, counties, cities, towns, prominent persons, etc. ... / with a supplementary volume devoted to selected personal history and reminiscence. Chicago: Standard Pub. Co., 1912.

- ^ Goodrich, Thomas. War to the Knife: Bleeding Kansas, 1854–1861. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1998.

- ^ Cutler, William G. History of the State of Kansas: Containing a Full Account of Its Growth from an Uninhabited Territory to a Wealthy and Important State; of Its Early Settlements; Its Rapid Increase in Population; and the Marvelous Development of Its Great Natural Resources Archived April 8, 2022, at the Wayback Machine. Chicago: A. T. Andreas, 1883.

- ^ Kansapedia: Kansas Territory Archived April 16, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Kansas Historical Society

- ^ Kansas Matters – Appeal to the South Archived October 30, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, De Bow's Review, Vol 20, Issue 5, May 1, 1856, pp. 635-639.

- ^ Barry, Louise. The Emigrant Aid Company Parties of 1854 and The Emigrant Aid Company Parties of 1855, Kansas Historical Quarterly 12 (1943): pp. 115–155, 227–268.

- ^ Carruth, William H. New England in Kansas, New England Magazine, Vol. 16, March 1897, pp. 3–21.

- ^ Border Ruffians Archived February 27, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, U.S. History Online Textbook

- ^ Phillips, Christopher (March 2002). 'The Crime against Missouri': Slavery, Kansas, and the Cant of Southernness in the Border West. Civil War History. Vol. 48. pp. 60–81.

- ^ Godsey, Flora Rosenquist (1925). The Early Settlement and Raid on the 'Upper Neosho'. Kansas Historical Collection, 1923–1925. Vol. 16. pp. 451–463.

- ^ "Bogus Legislature". Kansapedia. Kansas Historical Society. 2013 [2011]. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ Neely, Jeremy. The Border Between Them: Violence and Reconciliation on the Kansas-Missouri Line. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2007.

- ^ Oates, Stephen B. To Purge This Land With Blood: A Biography of John Brown. New York: Harper and Row, 1970.

- ^ Rein, Christopher.Battle of Osawatomie Archived January 4, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854–1865.

- ^ Emigrant Aid Organizations: Massachusetts State Kansas Committee Archived May 14, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, Territorial Kansas

- ^ Poole, W. Scott (2005). "Higginson, Thomas Wentworth". In Finkleman, Paul (ed.). Encyclopedia of African American History, 1619–1895: From the Colonial Period to the Age of Frederick Douglass. Oxford. ISBN 978-0195167771.

- ^ a b c d W. H. Isely. The Sharps Rifle Episode in Kansas History Archived May 14, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, The American Historical Review, Vol. 12, No. 3 (Apr. 1907), pp. 546–566.

- ^ Massachusetts State Kansas Aid Committee Report, September 1858 Archived April 27, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, West Virginia Archives and History

- ^ National Kansas Relief Committee, minutes Archived January 4, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Kansas Historical Society

- ^ Hinton, Richard Josiah. John Brown And His Men: With Some Account of the Roads They Traveled to Reach Harper's Ferry Archived May 14, 2022, at the Wayback Machine. New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1894, p. 122.

- ^ Rawley, James A. Race and Politics: "Bleeding Kansas" and the Coming of the Civil War Archived May 14, 2022, at the Wayback Machine. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1969.

- ^ O’Bryan, Tony. "Wyandotte Constitution," Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854–1865.

- ^ "Bleeding Kansas & the Missouri Border War". Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ O’Bryan, Tony. "Jayhawkers," Archived January 9, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854–1865

- ^ O'Bryan, Tony. "Red Legs," Archived March 2, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Civil War on the Western Border, The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854–1865

- ^ Cheatham, Gary L. 'Desperate Characters': The Development and Impact of the Confederate Guerrilla Conflict in Kansas, Kansas History 14 (Autumn 1991): 144–161. Archived

- ^ Gilmore, Donald L., The Kansas 'Red Legs' as Missouri's Dark Underbelly (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on March 16, 2021, retrieved March 16, 2021

Further reading

[edit]- Williams, Robert Hamilton. With the border ruffians; memories of the Far West, 1852–1868. New York: John Murray, 1907.

- Cutler, William G. History of the State of Kansas: Containing a Full Account of Its Growth from an Uninhabited Territory to a Wealthy and Important State; of Its Early Settlements; Its Rapid Increase in Population; and the Marvelous Development of Its Great Natural Resources. Chicago: A. T. Andreas, 1883.

- Gladstone, Thomas H. The Englishman In Kansas: Or, Squatter Life and Border Warfare. New York: Miller & Company, 1857.

- Anonymous (June 11, 1857). "Song of the border ruffian". Montreal Gazette. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- Greeley, Horace. A History of the Struggle for Slavery Extension or Restriction in the United States. New York: Dix, Edwards and Company, 1856.

- Phillips, William Addison. The conquest of Kansas, by Missouri and her allies. A history of the troubles in Kansas, from the passage of the organic act until the close of July 1856. Boston: Philips, Sampson and company, 1856.

External links

[edit]- Bad Blood, the Border War that Triggered the Civil War, DVD documentary. Kansas City MO: Kansas City Public Television (KCPT) and Wide Awake Films, 2007. ISBN 0-9777261-4-2

- Time Line: Bleeding Kansas, Archived March 13, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Center for Great Plains Studies, Emporia State University

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch