Boyz n the Hood

| Boyz n the Hood | |

|---|---|

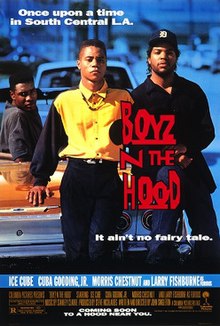

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Singleton |

| Written by | John Singleton |

| Produced by | Steve Nicolaides |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Charles Mills |

| Edited by | Bruce Cannon |

| Music by | Stanley Clarke |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 112 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $5.7–6.5 million[1][2] |

| Box office | $57.5 million[2] |

Boyz n the Hood is a 1991 American coming-of-age hood crime drama film written and directed by John Singleton in his feature directorial debut.[3] It stars Cuba Gooding Jr., Ice Cube (in his film debut), Morris Chestnut, and Laurence Fishburne (credited as Larry Fishburne), with Nia Long, Tyra Ferrell, Regina King, and Angela Bassett in supporting roles. Boyz n the Hood follows Jason "Tre" Styles III (Gooding Jr.), who is sent to live with his father Jason "Furious" Styles Jr. (Fishburne) in South Central Los Angeles, surrounded by the neighborhood's booming gang culture, where he reunites with his childhood friends. The film's title is a reference to the 1987 Eazy-E rap song of the same name, written by Ice Cube.

Singleton initially developed the film as a requirement for his application to film school in 1986 and sold the script to Columbia Pictures upon graduation in 1990. During writing, he drew inspiration from his own life and from the lives of people he knew and insisted he direct the project. Principal photography began in September 1990 and was filmed on location from October to November 1990. The film features breakout roles for Ice Cube, Gooding Jr., Chestnut, and Long.

Boyz n the Hood was screened in the Un Certain Regard section at the 1991 Cannes Film Festival.[4] It premiered in Los Angeles on July 2, 1991, and was theatrically released in the United States ten days later. The film became a critical and commercial success, grossing $57.5 million in North America and earning nominations for Best Director and Best Original Screenplay at the 64th Academy Awards. Singleton became the youngest person and the first African American to be nominated for Best Director. In 2002, the United States Library of Congress deemed it "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry.[5][6]

Plot

[edit]In 1984, ten-year-old Jason "Tre" Styles III lives with his single mother, Reva Devereaux, in Inglewood, California. After Tre gets into a fight at school, his teacher informs Reva that although intelligent, he lacks maturity and respect. Concerned about Tre's future, Reva sends him to live in the Crenshaw neighborhood of South Central with his father, Jason "Furious" Styles Jr., hoping Tre will learn life lessons from him. Although strict, Furious is also caring and attentive.

In Crenshaw, Tre reunites with his childhood friends Darrin "Doughboy" Baker, Doughboy's half-brother Ricky, and their friend Chris. One night, Furious calls the LAPD after shooting at a burglar with his revolver, and a civil and professional white police officer named Graham and a hostile and self-hating black police officer named Coffey arrive an hour later. The next day at Chris's suggestion, Tre and his friends go to witness a dead body, after which a group of older boys harasses them. Later on, en route back from a fishing trip, Tre and Furious notice Doughboy and Chris being arrested for theft.

Seven years later, Doughboy, now a Rollin 60s Crips member, is released from prison. Attending his welcome home party are Chris, now paraplegic due to a gunshot wound, and new friends and fellow Crip members Dookie and Monster. Ricky, now a star running back at Crenshaw High School who hopes to earn a university scholarship, lives with his mother Brenda, girlfriend Shanice, and their toddler son. A visiting USC recruiter implores him to score at least a 700 on the SAT to qualify for the scholarship. Meanwhile, Tre, now a mature and responsible teenager, hopes to attend college with his girlfriend Brandi.

Later during a street gathering on Crenshaw Blvd, Ferris, a Crenshaw Mafia Bloods member, provokes Ricky. Everybody comes to Ricky's defense, before Doughboy confronts Ferris and brandishes his Colt Double Eagle, leading to an argument between the gangs. Cooler heads prevail until Ferris fires an automatic MAC-10 into the air, forcing everybody to flee. Afterwards, Tre and Ricky are pulled over by an LAPD patrol car where Coffey threateningly holds his gun at Tre's throat. A distraught Tre ventures to Brandi's house, where he breaks down. After she comforts him, they have sexual intercourse for the first time.

The next afternoon, Brenda asks Ricky to run an errand, and Ricky encounters and brawls with Doughboy, with Brenda taking Ricky's side, and berating Doughboy. As he and Tre depart, Ricky's SAT results are delivered. The duo notice Ferris and the Bloods driving around and cut through back alleys to avoid them before splitting up; unfortunately, the Bloods approach Ricky, one of whom fatally shoots him in the leg and chest with a sawed off shotgun, killing him. A distraught Doughboy helps Tre carry Ricky's bloodied corpse home; afterwards, Brenda and Shanice, both devastated by Ricky's death, tearfully blame Doughboy for instigating the shooting. Later, Brenda discovers that Ricky scored a 710, enough to qualify for the scholarship he sought.

Angered, the remaining boys vow vengeance on the Bloods. Furious finds Tre preparing to take his gun but seemingly convinces him to abandon his plans for revenge; moments later, he and Brandi catch Tre sneaking out to join Doughboy, Dookie and Monster. Later, as the gang drives around the city, Tre comes to his senses, quits and returns home. After the gang coincidentally locates the Bloods at a local diner, Monster guns down the fleeing trio with an AK-47 he bought, murdering one of them by shooting him three times in the back, while Doughboy executes Ricky's killer, shooting him once in the spine, and Ferris twice in the head in a vengeful situation. Later that evening, when Tre arrives home, he and Furious silently stare at each other before entering their bedrooms for the night.

The next morning, Doughboy visits Tre, understanding Tre's reasons for abandoning the gang. Knowing he will face retaliation for killing Ferris and accepting the consequences of his crime-ridden life, Doughboy questions why most people "don't know, don't show, or don't care about what's going on in the hood" and laments Ricky's death. Tre embraces him as a surrogate brother.

As Doughboy leaves and Tre goes back into his house, a postscript reveals that Ricky was buried the next day, Doughboy was murdered two weeks later, and Tre ultimately attended college with Brandi in Atlanta.

Cast

[edit]- Cuba Gooding Jr. as Jason "Tre" Styles III (age 17)

- Desi Arnez Hines II as Jason "Tre" Styles III (age 10)

- Ice Cube as Darrin "Doughboy" Baker (age 18)

- Baha Jackson as Doughboy (age 11)

- Laurence Fishburne (credited as Larry Fisburne) as Jason "Furious" Styles Jr.

- Nia Long as Brandi (age 17)

- Nicole Brown as Brandi (age 10)

- Morris Chestnut as Ricky Baker (age 17)

- Donovan McCrary as Ricky (age 10)

- Tyra Ferrell as Brenda Baker

- Angela Bassett as Reva Devereaux

- Regina King as Shalika

- Redge Green as Chris "Little Chris" (age 17)

- Kenneth A. Brown as Chris (age 10)

- Dedrick D. Gobert as "Dooky"

- Baldwin C. Sykes as "Monster"

- Alysia Rogers as Shanice

- Tracey Lewis-Sinclair as Shaniqua

- Meta King as Brandi's mother

- Whitman Mayo as the old man

- Lexie Bigham as "Mad Dog"

- Raymond Turner as Ferris

- Lloyd Avery II as Knucklehead #2

- John Singleton as the mailman

- Kirk Kinder as Officer Graham

- Jessie Lawrence Ferguson as Officer Coffey[7]

Production

[edit]Singleton wrote the film based on his own life and that of people he knew.[8] When applying for film school, one of the questions on the application form was to describe "three ideas for films". One of the ideas Singleton composed was titled Summer of 84, which later evolved into Boyz n the Hood.[8] During writing, Singleton was influenced by the 1986 film Stand by Me, which inspired both an early scene where four young boys take a trip to see a dead body and the closing fade-out of main character Doughboy.[8]

Upon completion, Singleton was protective of his script, insisting that he be the one to direct the project, later explaining at a retrospective screening of the film "I wasn't going to have somebody from Idaho or Encino direct this movie."[3] He sold the script to Columbia Pictures in 1990, who greenlit the film immediately out of interest in making a film similar to the comedy-drama film Do the Right Thing (1989).

The role of Doughboy was written specially for Ice Cube, whom Singleton met while working as an intern at The Arsenio Hall Show.[8] Singleton also noted the studio was unaware of Ice Cube's standing as a member of rap group N.W.A.[8] Singleton claims Gooding and Chestnut were cast because they were the first ones who showed up to auditions,[8] while Fishburne was cast after Singleton met him on the set of Pee-wee's Playhouse, where Singleton worked as a production assistant and security guard.[9]

Long grew up in the area the film depicts and has said, "It was important as a young actor to me that this feels real because I knew what it was like go home from school and hear gunshots at night." Bassett referred to Singleton as her "little brother" on set. "I'd been in LA for about three years and I was trying, trying, trying to do films," she said. "We talked, I auditioned and he gave me a shot. I've been waiting to work with him ever since."[3]

The film was shot in sequence, with Singleton later noting that as the film goes on, the camera work gets better as Singleton was finding his foothold as a director.[3] He has a cameo in the film, appearing as a mailman handing over mail to Brenda as Doughboy and Ricky are having a scuffle in the front yard. Filming began on October 1, 1990 in South Central Los Angeles, with several gang members serving as consultants, on "wardrobe, vocal emphasis and dialogue changes" to ensure authenticity.[1]

Reception and legacy

[edit]Critical response

[edit]Review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes gives the film an approval rating of 96% based on 71 reviews and an average score of 8.40/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Well-acted and thematically rich, Boyz n the Hood observes urban America with far more depth and compassion than many of the like-minded films its success inspired."[10] At Metacritic, the film received an average score of 76 out of 100 based on 20 reviews, which indicates "generally favorable reviews".[11]

Cultural impact

[edit]Boyz n the Hood launched the acting careers of Gooding, Cube, Chestnut, Long and King, who were given their first major leading roles in the film, as well as the first significant film role for Angela Bassett[3] Along with Colors (1988) and Do the Right Thing (1989), Boyz n the Hood is credited as a notable pioneer of the hood film genre, with its success leading to American hood films such as New Jack City (also 1991), Juice (1992), Menace II Society (1993), Friday (1995), Training Day (2001), 8 Mile (2002), Hustle & Flow, Get Rich or Die Tryin' (both 2005), Dope, Straight Outta Compton (both 2015) and The Hate U Give (2018).

For his work, Singleton earned nominations for Best Director and Best Original Screenplay at the 64th Academy Awards, making him the youngest person and first African American to be nominated for Best Director. Since then, the only black nominees in the category have been Lee Daniels, Steve McQueen, Barry Jenkins, Jordan Peele and Spike Lee. In 2002, the United States Library of Congress deemed the film to be "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry.

Accolades

[edit]- In 2007, Boyz n the Hood was selected as one of the 50 Films To See in your lifetime by Channel 4.

American Film Institute Lists

[edit]In popular culture

[edit]Australian alternative rock band TISM released a live VHS called Boyz n the Hoods in 1992, whose cover artwork is presented as a parody of the film's original VHS box, albeit with a fake disclaimer printed on the cover stating that due to a manufacturing error, the non-existent film was replaced with TISM's concert.

Characters and scenes from Boyz n the Hood are parodied in the 1996 crime comedy parody film, Don't Be a Menace to South Central While Drinking Your Juice in the Hood.

In the film Be Kind Rewind, the VHS of Boyz n the Hood was among the erased VHS tapes that were "sweded" by the main characters.

In the 2015 comedy film Get Hard, Kevin Hart's character Darnell is asked to talk about the reason for his fabricated incarceration years earlier. Fumbling for a story, he describes the final scene of Boyz n the Hood, passing it off as his own experience to Will Ferrell's character.

In the series finale of the show Snowfall, which Singleton co-wrote, co-created, co-executive produced and directed, the main characters Leon and Franklin walk by someone filming a movie on the street that looks very much like a scene with the young boys from John Singleton's Boyz n the Hood as a homage to the creator.

Soundtrack

[edit]| Year | Album | Peak chart positions | Certifications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. | U.S. R&B | |||

| 1991 | Boyz n the Hood

| 12 | 1 | |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Catalogue–Boyz N the Hood". AFI. Retrieved January 24, 2024.

- ^ a b "Boyz N the Hood". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Smith, Nigel M (June 13, 2016). "John Singleton reflects on Boyz N the Hood: 'I didn't know anything'". The Guardian. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- ^ "Boyz n the Hood". Cannes Film Festival. Retrieved August 9, 2009.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". National Film Preservation Board. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- ^ "Librarian of Congress Adds 25 Films to National Film Registry". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- ^ "'Boyz n the Hood' Dirty Cop Actor Jessie Lawrence Ferguson Dead at 76". TMZ. April 27, 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Jones, Will (November 1, 2016). "Talking 'Boyz N the Hood' with Its Director John Singleton". Vice UK. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- ^ "John Singleton Interview Part 1 of 3 - TelevisionAcademy.com/Interviews". Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Foundation. 24 September 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ "Boyz n the Hood (1991)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved September 12, 2024.

- ^ "Boyz n the Hood Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved September 11, 2011.

- ^ "The 64th Academy Awards (1992) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- ^ "1988-2013 Award Winner Archives". Chicago Film Critics Association. January 1, 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ "The Annual 17th Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards". Los Angeles Film Critics Association. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ "1991 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "1991 New York Film Critics Circle Awards". Mubi. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Film Hall of Fame Productions". Online Film & Television Association. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ "Awards Winners". Writers Guild of America Awards. Archived from the original on 2012-12-05. Retrieved 2010-06-06.

- ^ "Thirteenth Annual Youth in Film Awards: 1990–1991". Young Artist Awards. Archived from the original on April 3, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2010.

- ^ "RIAA Gold & Platinum Searchable Database - Tony! Toni! Tone![permanent dead link]". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

External links

[edit]- Boyz n the Hood at IMDb

- Boyz n the Hood at the TCM Movie Database

- Boyz n the Hood at AllMovie

- Boyz n the Hood at Box Office Mojo

- Boyz n the Hood at Rotten Tomatoes

- Boyz n the Hood at Metacritic

- Boyz n the Hood essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010, ISBN 0826429777, pages 806–807

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch