Broadhurst Theatre

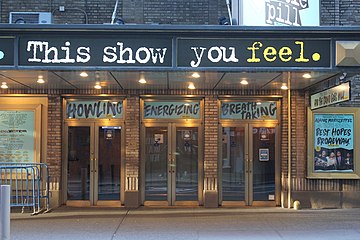

Playing Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune, July 2019 | |

| |

| Address | 235 West 44th Street Manhattan, New York City United States |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°45′30″N 73°59′15″W / 40.7582°N 73.9876°W |

| Owner | The Shubert Organization |

| Type | Broadway theatre |

| Capacity | 1,218 |

| Production | The Hills of California |

| Construction | |

| Opened | September 27, 1917 |

| Architect | Herbert J. Krapp |

| Website | |

| shubert | |

| Designated | November 10, 1987[1] |

| Reference no. | 1323[1] |

| Designated entity | Facade |

| Designated | December 15, 1987[2] |

| Reference no. | 1324[2] |

| Designated entity | Auditorium interior |

The Broadhurst Theatre is a Broadway theater at 235 West 44th Street in the Theater District of Midtown Manhattan in New York City. Opened in 1917, the theater was designed by Herbert J. Krapp and was built for the Shubert brothers. The Broadhurst Theatre is named for British-American theatrical producer George Broadhurst, who leased the theater before its opening. It has 1,218 seats across two levels and is operated by The Shubert Organization. Both the facade and the auditorium interior are New York City landmarks.

The neoclassical facade is simple in design and is similar to that of the Schoenfeld (formerly Plymouth) Theatre, which was developed concurrently. The Broadhurst's facade is made of buff-colored brick and terracotta and is divided into two sections: a stage house to the west and the theater's entrance to the east. The entrance is topped by fire-escape galleries and contains a curved corner facing east toward Broadway. The auditorium contains an orchestra level, a large balcony, a small technical gallery, and a flat ceiling. The space is decorated in the classical Greek and Adam styles, with Doric columns and Greek friezes. Near the front of the auditorium, flanking the flat proscenium arch, are box seats at balcony level.

The Shubert brothers developed the Broadhurst and Plymouth theaters following the success of the Booth and Shubert theaters directly to the east. The Broadhurst Theatre opened on September 27, 1917, with Misalliance; its namesake had intended to use the theater for his own productions. The Shuberts acquired full control of the Broadhurst in 1929 and have operated it since then. The theater has hosted not only musicals but also revues, comedies, and dramas throughout its history. Long-running shows hosted at the Broadhurst have included Hold Everything!, Fiorello!, Cabaret, Grease, Kiss of the Spider Woman, Les Misérables, and Mamma Mia!.

Site

[edit]The Broadhurst Theatre is on 235 West 44th Street, on the north sidewalk between Eighth Avenue and Seventh Avenue, near Times Square in the Theater District of Midtown Manhattan in New York City.[3][4] The rectangular land lot covers 10,695 square feet (993.6 m2), with a frontage of 106.5 feet (32.5 m) on 44th Street and a depth of 100.42 ft (31 m).[4] The Broadhurst Theatre shares the city block with the Row NYC Hotel to the west. It adjoins six other theaters: the Majestic to the west, the John Golden and Bernard B. Jacobs to the northwest, the Gerald Schoenfeld to the north, the Booth to the northeast, and the Shubert to the east. Other nearby structures include the Music Box Theatre and Imperial Theatre one block north; One Astor Plaza to the east; 1501 Broadway to the southeast; and the Sardi's restaurant, the Hayes Theater, and the St. James Theatre to the south.[4]

The Broadhurst is part of the largest concentration of Broadway theaters on a single block.[5] The Broadhurst, Schoenfeld (originally Plymouth), Booth, and Shubert theaters were all developed by the Shubert brothers between 44th and 45th Streets, occupying land previously owned by the Astor family.[6][7] The Broadhurst and Schoenfeld were built as a pair, occupying land left over from the development of the Shubert and Booth, which were also paired.[8][9] The Broadhurst/Schoenfeld theatrical pair share an alley to the east, parallel to the larger Shubert Alley east of the Shubert/Booth pair.[6][10] The Broadhurst/Schoenfeld alley was required under New York City construction codes of the time but, unlike Shubert Alley, it was closed to the public shortly after its completion.[11] The Shuberts bought the land under all four theaters from the Astors in 1948.[7][12]

Design

[edit]The Broadhurst Theatre was designed by Herbert J. Krapp and constructed in 1917 for the Shubert brothers.[3][13] The Broadhurst and Plymouth were two of Krapp's first theatrical designs as an independent architect after he left the firm of Herts & Tallant.[14] While the facades of the two theaters are similar in arrangement, the interiors have a different design both from each other and from their respective facades.[15][16] The Broadhurst is designed to complement the Shubert/Booth theatrical pair, with a simple neoclassical facade compared to the Shubert's and Booth's "Venetian Renaissance" designs.[17] The Broadhurst is operated by the Shubert Organization.[18][19]

Facade

[edit]Krapp designed the Broadhurst and Plymouth theaters with relatively simple brick-and-stone facades, instead relying on the arrangement of the brickwork for decorative purposes. The Broadhurst and Plymouth contain curved corners at the eastern portions of their respective facades, facing Broadway, since most audience members reached the theaters from that direction.[14][15] The use of simple exterior-design elements was typical of Krapp's commissions for the Shubert family,[14][16] giving these theaters the impression that they were mass-produced.[16] The Broadhurst and Plymouth theaters' designs contrasted with Henry Beaumont Herts's earlier ornate designs of the Shubert and Booth theaters. Nevertheless, the use of curved east-facing corners was common to all four theaters.[14] The Broadhurst's facade is divided into two sections: the auditorium to the east and a stage house to the west. The facade is generally shorter than its width.[20]

Auditorium section

[edit]The ground floor of the auditorium contains a water table made of granite, above which are vertical blocks of architectural terracotta. The rest of the facade is made of buff brick in Flemish bond, laid in a diaper pattern. Along the ground floor on 44th Street, there are glass-and-bronze double doors with aluminum frames and transoms. There are display boxes on either side of these doors, and a marquee extends above the doors. The southeastern corner of the facade is curved and contains an entrance to the ticket lobby. This entrance contains a double door, above which is a glass transom panel with the word "Broadhurst" inscribed on it.[20][21] The corner entrance is topped by a broken pediment, which is supported by console brackets on either side and contains an escutcheon at the center.[9][20]

Along 44th Street, the auditorium's second and third floors contain a fire escape made of cast iron and wrought iron. There are doors and windows on both levels, leading to the fire escape. In addition, the fire escape's third-floor railing contains cast-iron depictions of ribands and shields.[20][21] A canopy originally shielded the fire escape at the third floor.[21] Above the center of the third floor, on 44th Street, is a terracotta cartouche containing depictions of swags. The curved corner contains a third-floor window, topped by an oval escutcheon decorated with swags and fleur-de-lis. A terracotta cornice and a brick parapet runs above the auditorium facade.[20][21] The parapet is stepped and contains a coping made of sheet metal.[20]

Stage house

[edit]

The stage house is five stories high. The ground floor of the stage house contains a granite water table with terracotta blocks above it. On this story, there are two metal doors and three windows. The stage house has five sash windows on each of the upper stories. These windows are placed within segmental arches made of brick. There is a metal fire escape in front of the stage house, which leads to the fire escape in front of the auditorium's third story. A parapet with corbels runs above the fifth story of the stage house.[20]

Auditorium

[edit]The auditorium has an orchestra level, one balcony, boxes, and a stage behind the proscenium arch. The auditorium has about the same width and depth, and the space is designed with plaster decorations in relief.[22] According to the Shubert Organization, the theater has 1,218 seats;[18] meanwhile, The Broadway League gives a figure of 1,186 seats[23] and Playbill cites 1,163 seats.[19] The physical seats are divided into 733 seats in the orchestra, 429 on the balcony, and 24 in the boxes. There are 32 standing-only spots.[18] The theater contains restrooms in the basement and concessions in the lobby.[19] The orchestra level is wheelchair-accessible and contains an accessible restroom; the balcony is not wheelchair-accessible.[18]

Seating areas

[edit]The rear or eastern end of the orchestra contains a promenade, with four paneled piers supporting the balcony level. The promenade's ceiling is surrounded by a Doric-style cornice as well as a frieze designed in the Adam style.[22] There are also plasterwork panels on the promenade ceiling, which contain chandeliers suspended from medallions.[24] Two staircases with metal railings lead from the promenade to the balcony.[25] The orchestra level is raked, sloping down toward an orchestra pit in front of the stage. The orchestra and its promenade contain walls with plasterwork panels. Doorways on the south (left) wall lead from the lobby, while those on the north (right) and east (rear) walls lead to the exits.[24] The tops of the doorways are flanked by console brackets, which support an entablature and a pediment with anthemia.[22] When the theater was built, the orchestra had a movable floor;[26] half the seating could be removed overnight to accommodate smaller productions.[27][28]

At the rear of the balcony are four paneled piers (corresponding to those at orchestra level), which are topped by Doric-style capitals.[25] The side walls contain plasterwork panels with swags. There are also doorways with pediments, similar to those on the orchestra.[9][25] Low-relief panels and air-conditioning vents are placed on the balcony's underside. In front of the balcony is a Panathenaic frieze, based on that of the Parthenon, which is mostly hidden behind light boxes.[25] There is a small technical gallery above the rear of the balcony, the front railing of which contains moldings of swags. A Doric-style cornice runs above the balcony walls, wrapping above the boxes and proscenium.[24]

On either side of the stage is a wall section with three boxes at the balcony level. The boxes step downward toward the stage; the front box curves forward into the proscenium arch, while the rear box curves backward into the balcony.[9][22] At the orchestra level, there are three rectangular openings, corresponding to the locations of former boxes on that level. The front railings of the boxes contain sections of a Panathenaic frieze, separated by fasces made of plaster;[25] the frieze contained depictions of horsemen.[9] The underside of each box is decorated with a medallion containing a light fixture; this is surrounded by a molded band.[25] Doric-style columns separate the boxes from each other, supporting a molding and panel at the top of each wall section.[9][25]

Other design features

[edit]Next to the boxes is a flat proscenium arch, which consists of Doric pilasters on either side of the opening, as well as an entablature above.[22] The entablature contains a central relief panel with a frieze of horsemen.[9][22] The theater was also designed with a false proscenium opening, which gave the impression of a smaller stage suitable for dramas and comedies.[27] The proscenium opening measures about 25 feet (7.6 m) tall and 40 ft (12 m) wide. The depth of the auditorium to the proscenium is 31 ft (9.4 m), while the depth to the front of the stage is 33 ft 2 in (10.11 m).[18] The ceiling is flat, containing plasterwork moldings, friezes, and medallions, as well as air-conditioning vents. Chandeliers are suspended from the medallions.[25]

History

[edit]Times Square became the epicenter for large-scale theater productions between 1900 and the Great Depression.[29] Manhattan's theater district had begun to shift from Union Square and Madison Square during the first decade of the 20th century.[30][31] From 1901 to 1920, forty-three theaters were built around Broadway in Midtown Manhattan, including the Broadhurst Theatre.[32] The Broadhurst was developed by the Shubert brothers of Syracuse, New York, who expanded downstate into New York City in the first decade of the 20th century.[33][34] After the death of Sam S. Shubert in 1905, his brothers Lee and Jacob J. Shubert expanded their theatrical operations significantly.[35][36] The brothers controlled a quarter of all plays and three-quarters of theatrical ticket sales in the U.S. by 1925.[33][37]

Development and early years

[edit]The Shubert brothers had constructed the Shubert and Booth theaters as a pair in 1913, having leased the site from the Astor family.[8] Only the eastern half of the land was used for the Shubert/Booth project; following the success of the two theaters, the Shubert brothers decided to develop another pair of theaters to the west.[13] Herbert Krapp was hired as the architect, while Edward Margolies was the builder.[26] Krapp filed plans for a new theater at 235 West 44th Street with the New York City Department of Buildings in January 1917;[38] he revised these plans in March.[39] That August, British-American theatrical producer George Broadhurst leased the theater from the Shuberts, and the venue was renamed for Broadhurst.[27][28] At the time, Broadhurst was a busy playwright; he staged nearly 30 Broadway and West End plays from 1907 to 1924.[17][40] He leased the Shubert's new 44th Street venue because he wanted a theater to showcase his own work.[17]

The Broadhurst opened on September 27, 1917, with George Bernard Shaw's comedy Misalliance;[41][42] the show lasted 52 performances.[43][44] Despite his early intentions, George Broadhurst did not only stage his own shows at the theater;[45] for example, the Broadhurst hosted a revival of R. C. Carton's Lord and Lady Algy in December 1917.[46][47] This was followed in 1918 by the musical Maytime with Peggy Wood[45][48][49] and the play Ladies First with Nora Bayes and William Kent.[41][50] Rachel Crothers's comedy 39 East opened at the Broadhurst in 1919,[41][51][52] and Jane Cowl and Allan Langdon Martin's collaboration Smilin' Through at the end of that year.[53][54][55]

George Broadhurst's adaptation of the play Tarzan of the Apes, with real animals,[56][57] ran for 13 performances in 1921.[58][59] The Claw featuring Lionel Barrymore opened the same year.[58][60] Peggy Wood returned to the Broadhurst for Hugo Felix's Marjolaine in 1922,[58][61] which had 136 performances.[62] The Broadhurst's productions in 1923 included The Dancers with Richard Bennett and Florence Eldridge,[58][63][64] as well as the revue Topics of 1923 with Alice Delysia.[58][65] In early 1924, the Broadhurst staged Marc Connelly and George S. Kaufman's play Beggar on Horseback with Roland Young,[66][67] which lasted for 224 performances.[58][68] This was followed the next year by Michael Arlen's The Green Hat with Katharine Cornell;[66][69] it had 237 performances.[45][70]

The Broadhurst next hosted the revue Bunk of 1926, which was forced to close in June 1926 due to an injunction against it.[71] Shortly afterward, Alexander A. Aarons and Vinton Freedley leased the Broadhurst Theatre for several years.[72][73] Jed Harris's version of the George Abbott and Philip Dunning play Broadway opened that September;[66][74] it continued for 603 performances,[75][76] ultimately relocating at the end of 1927.[77] It was immediately followed by Winthrop Ames's version of Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice, featuring George Arliss and Peggy Wood.[75][78][79] The Lew Brown/B. G. de Sylva/Ray Henderson musical Hold Everything! opened later in 1928[80][81] and lasted for 413 performances.[75][82] The Broadhurst's last hit of the 1920s was George S. Kaufman and Ring Lardner's play June Moon, which opened in 1929 for a 273-performance run.[75][83] That year, the Shuberts took over the theater's operation from George Broadhurst.[6]

1930s and 1940s

[edit]

In 1931, the Broadhurst staged Herbert Fields and Rodgers and Hart's musical America's Sweetheart,[84] which continued for 135 performances.[85][86] Aarons and Freedley gave up their lease on the theater that August,[87] and Norman Bel Geddes produced a short-lived revival of Shakespeare's Hamlet that November.[85][88] This was followed in 1932 by Philip Barry's comedy The Animal Kingdom;[85][89][90] the drama The Man Who Reclaimed His Head;[91][92] and Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur's play Twentieth Century.[93][94][95] Next, the Group Theatre occupied the Broadhurst during the 1933–1934 season with a production of Sidney Kingsley's play Men in White.[91][96][97] Eve Le Gallienne's Civic Repertory Company presented several shows at the Broadhurst later in 1934.[98][99] This included L'Aiglon with Ethel Barrymore,[100][101] as well as Hedda Gabler and Cradle Song.[98]

The Broadhurst hosted Robert E. Sherwood's play The Petrified Forest, with Humphrey Bogart and Leslie Howard, in 1935.[93][102][103] Victoria Regina, featuring Helen Hayes and Vincent Price, opened at the end of that year.[93][104] It ran for 517 performances through 1937,[105] with a hiatus mid-run.[106] Subsequently, Ruth Gordon's version of the Henrik Ibsen play A Doll's House moved to the Broadhurst in 1938.[107][108] This was followed in 1939 by Dodie Smith's Dear Octopus;[107][109][110] the musical The Hot Mikado, an all-Black version of The Mikado with Bill Robinson;[111][112][113] and the revue The Streets of Paris with Carmen Miranda and Abbott and Costello.[111][114]

During the 1940s, the Broadhurst hosted numerous musicals and revues.[115] These included Boys and Girls Together with Ed Wynn, Jane Pickens, and the DeMarcos in 1940,[116][117] as well as High Kickers with George Jessel and Sophie Tucker the next year.[111][118][119] The drama Uncle Harry with Eva Le Gallienne, Joseph Schildkraut, and Karl Malden ran at the Broadhurst in 1942.[120][121] Further hits at the Broadhurst included Fats Waller's revue Early to Bed in 1943;[122][123] the Agatha Christie play Ten Little Indians in 1944,[124][125][126] and a transfer of the revue Follow the Girls with Jackie Gleason and Gertrude Niesen in 1945.[124][127] Morgan Lewis and Nancy Hamilton's revue Three to Make Ready transferred to the Broadhurst in 1946,[124][128] and Helen Hayes returned the same year in Anita Loos's Happy Birthday,[122][129] which ran for 564 performances.[124][130] Four revues were staged during 1948 and 1949: Make Mine Manhattan, Along Fifth Avenue, Lend an Ear, and Touch and Go.[131]

1950s to 1970s

[edit]

The 1950s saw several long-running shows,[122] though the earliest shows of the decade were short-lived.[132] For example, Martin Balsam and Walter Matthau starred in The Liar, which lasted only 12 performances in May 1950.[133][132] Douglass Watson and Olivia de Havilland starred in a 49-performance revival of Romeo and Juliet in 1951,[134][135] while the musical Flahooley ran just 40 performances afterward.[134][136][137] Conversely, the musical Seventeen ran for 180 performances later in 1951.[134][138] Next was the revival of the Rodgers and Hart musical Pal Joey in 1952, featuring Vivienne Segal and Harold Lang,[139][140] which at 542 performances ran longer than the original production.[141][142] The Spanish Theatre performed several plays in repertory at the Broadhurst in 1953,[143] followed thereafter by The Prescott Proposals with Katharine Cornell.[141][144] This was followed by long runs of Anniversary Waltz (1954) with Macdonald Carey and Kitty Carlisle; Lunatics and Lovers (1954) with Sheila Bond, Buddy Hackett, and Dennis King; and The Desk Set (1955) with Shirley Booth.[141]

The Broadhurst hosted Auntie Mame in 1956,[145][146] starring Rosalind Russell in her last Broadway appearance;[147] it ran for 639 performances.[147][148] This was followed in 1958 by the play The World of Suzie Wong with France Nuyen and William Shatner,[145][149] which lasted for 508 performances.[150][151] Next, Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick's musical Fiorello! opened at the Broadhurst in November 1959,[145][152] relocating over a year later in May 1961.[153][154] Noël Coward's musical Sail Away opened at the Broadhurst in October 1961 with Elaine Stritch,[155][156] running for 167 performances.[150][157] The next year, the Broadhurst briefly hosted the long-running musical My Fair Lady,[158][159] and Richard Rodgers's musical No Strings finished its 580-performance run there.[160][161] The Tom Jones/Harvey Schmidt musical 110 in the Shade opened in 1963 with Robert Horton, Will Geer, Lesley Ann Warren, and Inga Swenson.[162][163] The next year, the theater hosted the West End musical Oh, What a Lovely War!.[160][164]

The musical Kelly was a flop in 1965, with just one performance before it closed.[165][166] It was followed the same year by the West End musical Half a Sixpence with Tommy Steele,[167][168] which ran for 512 performances.[169] Afterward, in late 1966, the Broadhurst premiered John Kander and Fred Ebb's Cabaret,[170] which only stayed a short time at the Broadhurst but ultimately lasted for about 1,165 performances.[171][172] More Stately Mansions, the last play by Eugene O'Neill, opened at the Broadhurst in 1967[173][174] and featured Ingrid Bergman, Arthur Hill, and Colleen Dewhurst.[171][175] You Know I Can't Hear You When the Water's Running occupied the Broadhurst for several months in 1968, during the middle of that play's run.[176][177] The next year, The Fig Leaves Are Falling flopped after four performances,[178] and Woody Allen, Tony Roberts, and Diane Keaton starred in Play It Again, Sam.[167][179][180]

The Broadhurst was increasingly hosting musicals, dramas, and comedies by the 1970s, with the decline of revues.[181] George Furth's Twigs, featuring Sada Thompson, opened at the theater in 1971.[182][183][184] Next, Grease had a short run at the Broadhurst during 1972;[185][186] after transferring elsewhere, the show became Broadway's longest-running musical.[182][186] It was followed at the end of the year by Neil Simon's The Sunshine Boys.[182][187][188] Herb Gardner's play Thieves was performed at the Broadhurst in 1974,[189][190] and the Royal Shakespeare Company's revival of Sherlock Holmes opened that year, with John Wood.[191][192][193] Productions shown at the Broadhurst in 1976 included Enid Bagnold's drama A Matter of Gravity, with Katharine Hepburn and Christopher Reeve;[191][194][195] a brief run of the musical Godspell, which had been an off-Broadway hit;[196][197][198] and A Texas Trilogy, a set of plays by Preston Jones.[191][199][200] At the end of the year, the theater hosted Larry Gelbart's farce Sly Fox, starring George C. Scott,[201][202] which ran for 495 performances.[203][204]

1980s and 1990s

[edit]Bob Fosse's musical Dancin' , starring Ann Reinking and Wayne Cilento, had opened in March 1978.[205][206] When Dancin' relocated in December 1980,[207][208] it had had the longest continuous run at the Broadhurst.[209][a] Immediately afterward, the Broadhurst hosted Peter Shaffer's Amadeus, with Ian McKellen, Tim Curry, and Jane Seymour;[210][211] it ran until October 1983.[207][212] The Tap Dance Kid opened that December,[213] running for three months before transferring.[207][214] Next was a revival of Death of a Salesman with Dustin Hoffman,[215] which opened in March 1984[216][217] and ran until the end of that year.[218] The Broadhurst was then closed for six months, and the firm of Johansen-Bhavnani renovated the venue as part of a project that cost $2 million. The project entailed rebuilding the stage, redecorating the lobby, enlarging a lounge and restrooms, and modifying the seating areas.[219] This was part of a restoration program for the Shubert Organization's Broadway theaters.[220]

The Broadhurst reopened in June 1985 with a gender-swapped version of Neil Simon's play The Odd Couple;[221][222] it lasted until February 1986.[223] The Eugene O'Neill play Long Day's Journey into Night opened at the theater in April 1986, with Bethel Leslie and Jack Lemmon,[224][225] followed later that year by the Royal Shakespeare Company's production of The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, with Roger Rees.[226][227] At the end of 1986, Neil Simon's Broadway Bound opened at the Broadhurst with Jason Alexander, Linda Lavin, and Phyllis Newman;[228][229] it ran for 756 performances over the next two years.[230][231] Another Simon play, Rumors, opened at the Broadhurst in November 1988[232][233] and ran for just over a year.[234]

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) had started considering protecting the Broadhurst as an official city landmark in 1982,[235] with discussions continuing over the next several years.[236] The LPC designated the facade as a landmark on November 10, 1987,[237][238][239] followed by the interior on December 15.[2] This was part of the LPC's wide-ranging effort in 1987 to grant landmark status to Broadway theaters.[240] The New York City Board of Estimate ratified the designations in March 1988.[241] The Shuberts, the Nederlanders, and Jujamcyn collectively sued the LPC in June 1988 to overturn the landmark designations of 22 theaters, including the Broadhurst, on the merit that the designations severely limited the extent to which the theaters could be modified.[242] The lawsuit was escalated to the New York Supreme Court and the Supreme Court of the United States, but these designations were ultimately upheld in 1992.[243]

The Andrew Lloyd Webber musical Aspects of Love opened at the Broadhurst in April 1990;[244][245] despite running for 377 performances,[246] the show lost its entire investment of $8 million.[247] Several short-lived shows followed,[248] including André Heller's Wonderhouse in 1991,[249][250] as well as a revival of Private Lives with Joan Collins[251][252] and the play Shimada in 1992.[253][254] The next hit was Terrence McNally, John Kander, and Fred Ebb's musical Kiss of the Spider Woman, which opened in May 1993 with Anthony Crivello, Brent Carver, and Chita Rivera;[255][256] it ran for 906 performances.[257][258] Next, the New York Shakespeare Festival presented The Tempest in November 1995, starring Patrick Stewart,[259][260] for 71 performances.[261][262] The play Getting Away with Murder flopped in March 1996 after 17 performances,[263][264] and the musical Once Upon a Mattress opened that December with Sarah Jessica Parker,[265][266] running for 187 performances.[267] In 1998, Jerry Seinfeld performed an original stand-up act at the Broadhurst; his final performance, I'm Telling You for the Last Time, was aired live on HBO.[268] This was followed by Fosse, a revue featuring Bob Fosse shows, which opened in January 1999[269][270] and ran for two and a half years.[271]

2000s to present

[edit]

The Broadhurst hosted a revival of the August Strindberg play Dance Of Death in late 2001, featuring Ian McKellen and Helen Mirren.[272][273] The next year, the theater revived Stephen Sondheim's musical Into the Woods with Vanessa Williams,[274] which ran for 279 performances.[275] Two short runs followed in 2003: Urban Cowboy, with 60 performances,[276][277] and Never Gonna Dance, with 84 performances.[278][279] As part of a settlement with the United States Department of Justice in 2003, the Shuberts agreed to improve disabled access at their 16 landmarked Broadway theaters, including the Broadhurst.[280][281] Billy Crystal's solo show 700 Sundays, which opened in December 2004,[282][283] ran for 163 performances[284] and at one point was Broadway's highest-grossing non-musical show.[285][286] The musical Lennon then had 49 performances at the Broadhurst in 2005,[287][288] followed the next year by Alan Bennett's play The History Boys.[286][289]

A revival of the musical Les Misérables opened in November 2006, just three years after the long-running original production had closed;[290][291] it had 463 performances.[292] More revivals followed in 2008, with an all-Black cast in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,[293][294] as well as a revival of Equus starring Daniel Radcliffe and Richard Griffiths.[295][296] Next in 2009 was a production of Friedrich Schiller's Mary Stuart, starring Janet McTeer and Harriet Walter,[297][298] and a West End transfer of Hamlet, starring Jude Law.[299][300] Meanwhile, the Shuberts sold 54,820 sq ft (5,093 m2) of unused air development rights above the Broadhurst to a developer in 2007;[301] this allowed the firm to profit from the site, since the theater was landmarked and could not be further developed.[302] A further 9,480 sq ft (881 m2) above the Broadhurst and Booth theaters was sold in 2009, and some 1,800 sq ft (170 m2) was sold in 2012.[301] The Shuberts sold a further 58,392 sq ft (5,424.8 m2) of air rights above the Majestic and Broadhurst in 2013.[303][304]

Lucy Prebble's play Enron flopped at the Broadhurst with 16 performances in 2010,[305][306] despite critical acclaim on the West End.[306][307] More successful was the Public Theatre's transfer of The Merchant of Venice, starring Al Pacino, the same year.[308][309] This was followed in 2011 by Floyd Mutrux's musical Baby It's You!.[310][311] Hugh Jackman's concert special Back on Broadway, which opened the same year,[312][313] broke the theater's box-office record several times;[314] the current record as of 2023[update] was set on the week ending January 1, 2012, when the show earned $2,057,354.[315] A revival of A Streetcar Named Desire with Blair Underwood and Nicole Ari Parker occupied the Broadhurst in 2012,[316][317] followed the next year by Nora Ephron's Lucky Guy, with Tom Hanks in his Broadway debut.[318][319] In 2013, the musical Mamma Mia! transferred from the Winter Garden Theatre to the Broadhurst for the final two years of its 14-year run.[320][321][322] The next shows at the Broadhurst were the play Misery in 2015,[323][324] as well as the musicals Tuck Everlasting[325][326] and The Front Page in 2016.[327][328]

The musical Anastasia opened at the Broadhurst in 2017 and ran there for nearly two years.[329][330] It was followed in May 2019 by Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune[331][332] and in December 2019 by Jagged Little Pill.[333][334] The theater closed on March 12, 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[335] It reopened on October 21, 2021, with performances of Jagged Little Pill,[336][337] which closed at the end of 2021 due to further pandemic-related issues.[338][339] It was followed in November 2022 by A Beautiful Noise, The Neil Diamond Musical,[340][341] which ran until June 2024.[342] A single performance of the musical Chess was also hosted at the Broadhurst in December 2022.[343] The next show to be staged at the Broadhurst, the play The Hills of California, opened at the Broadhurst in September 2024, running for two months;[344][345] this will be followed by Boop! The Betty Boop Musical in April 2025.[346][347]

Notable productions

[edit]Productions are listed by the year of their first performance.[19][23]

See also

[edit]- List of Broadway theaters

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Several previous shows had longer overall runs, but they had stayed at the Broadhurst for a shorter period.[209]

- ^ La Otra Honra, Cyrano de Bergerac, El Cardenal, Reinar Duspués de Morir, La Vida es Sueño, El Alcalde de Zalamea, Don Juan Tenorio

- ^ Rachael Lily Rosenbloom and Don't You Ever Forget It never officially opened at the Broadhurst Theatre; it only played previews.[388]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1987, p. 1.

- ^ a b White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ a b c "235 West 44 Street, 10036". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Bloom 2007, p. 37.

- ^ a b "Shuberts Buy Sites of Four of Their Theaters: Get Broadhurst, Plymouth, Shubert and Booth Land From W. W. Astor Estate". New York Herald Tribune. November 10, 1948. p. 14. ProQuest 1335171969.

- ^ a b Bloom 2007, p. 37; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d e f g Morrison 1999, p. 103.

- ^ Morrison 1999, p. 105.

- ^ Bloom 2007, p. 86.

- ^ Zolotow, Sam (November 10, 1948). "Shuberts Acquire 4 Broadway Sites; Purchase Choice Theatre Plots From William Astor Estate for Reported $3,500,000". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 13.

- ^ a b Morrison 1999, pp. 103, 105.

- ^ a b c Hirsch, Foster (2000). The Boys from Syracuse : the Shuberts' Theatrical Empire. Lanham: Cooper Square Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-4616-9875-3. OCLC 852759296.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d e "Broadhurst Theatre". Shubert Organization. September 27, 1917. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Broadhurst Theatre (1917) New York, NY". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d Morrison 1999, p. 102.

- ^ a b c d e f Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1987, p. 20.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (September 27, 1917). "Broadhurst Theatre – New York, NY". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1987, pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1987, p. 21.

- ^ a b Allen, Eugene Kelcey (August 1, 1917). "The Theatre". Women's Wear. Vol. 15, no. 26. p. 8. ProQuest 1666105574.

- ^ a b c "The Dramatic Stage: Broadhurst Realizes His Ambition to Have Theater". The Billboard. Vol. 29, no. 32. August 11, 1917. p. 18. ProQuest 1031520692.

- ^ a b "Theatre for Broadhurst; Playwright Leases New Building from the Shuberts". The New York Times. August 1, 1917. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ^ Swift, Christopher (2018). "The City Performs: An Architectural History of NYC Theater". New York City College of Technology, City University of New York. Archived from the original on March 25, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ "Theater District –". New York Preservation Archive Project. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 2.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 4.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 8.

- ^ Stagg 1968, p. 208.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 9.

- ^ Stagg 1968, p. 75.

- ^ Stagg 1968, p. 217.

- ^ "Contemplated Construction". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 99, no. 2550. January 27, 1917. p. 135 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Contemplated Construction". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 99, no. 2557. March 17, 1917. p. 380 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Broadhurst, 85, Playwright, Dead; Author of 'Wrong Mr. Wright,' 'A Fool and His Money' and Many Other Hit Shows". The New York Times. February 1, 1952. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c Bloom 2007, p. 37; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 99; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 17.

- ^ "Shaw Play Opens New Broadhurst". The Sun. September 28, 1917. p. 5. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ^ Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 99; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 25.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (September 27, 1917). "Misalliance – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"Misalliance (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1917)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 17.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (December 22, 1917). "Lord and Lady Algy – Broadway Play – 1917 Revival". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"Lord and Lady Algy (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1917)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ "Carton's Comedy Admirably Acted". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. December 24, 1917. p. 5. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (August 16, 1917). "Maytime – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"Maytime (Broadway, Sam S. Shubert Theatre, 1917)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ "'Maytime' Moves to the Broadhurst Theatre". New-York Tribune. April 2, 1918. p. 9. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (October 24, 1918). "Ladies First – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

"Ladies First (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1918)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022. - ^ a b The Broadway League (March 31, 1919). "39 East – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"39 East (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1919)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ "'39 East' to Move". New-York Tribune. July 13, 1919. p. 35. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c Bloom 2007, p. 37; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 99; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 26.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (December 30, 1919). "Smilin' Through – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"Smilin' Through (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1919)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ "Jane Cowl's Real Charm Shown in 'Smilin Through'". Daily News. January 1, 1920. p. 14. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 99.

- ^ "'Tarzan of the Apes' Here; Astonishing Play, With Lions and Monkeys, Entertains". The New York Times. September 8, 1921. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 101; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 27.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (September 7, 1921). "Tarzan of the Apes – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"Tarzan of the Apes (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1921)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ Whittaker, James (October 18, 1921). "'The Claw' Dig Into Vitals of Modern Politics". Daily News. p. 41. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ Whittaker, James (January 26, 1922). "Music Puts New Life in Step of 'Pomander Walk'". Daily News. p. 17. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (January 24, 1922). "Marjolaine – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

"Marjolaine (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1922)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022. - ^ a b The Broadway League (October 17, 1923). "The Dancers – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"The Dancers (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1923)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ Hammond, Percy (October 18, 1923). "The Theaters: "The Dancers" a Picturesque Melodrama From London Richard Bennett". New-York Tribune. p. 10. ProQuest 1331154878.

- ^ "Topics of 1923" for Broadhurst". The New York Times. November 16, 1923. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c Bloom 2007, p. 37; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 101; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 17.

- ^ "Drilling Suspended on Teapot Dome Lease; Operations Await Advices From Sinclair, Manager of the Company Says". The New York Times. February 17, 1924. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (February 12, 1924). "Beggar on Horseback – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"Beggar on Horseback (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1924)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ Hammond, Percy (September 16, 1925). "The Theaters: Miss Katherine Cornell Should Be Seen in Michael Arlen's "The Green Hat" Katharine Cornell". The New York Herald, New York Tribune. p. 18. ProQuest 1112839132.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (September 15, 1925). "The Green Hat – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"The Green Hat (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1925)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ ""Bunk of 1926" Closes; Ordered Shut by Play Jury, Revue Was Continued Under Injunction". The New York Times. June 22, 1926. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ "Musical Comedy: Aarons and Freedley Lease the Broadhurst". The Billboard. Vol. 38, no. 27. July 3, 1926. p. 26. ProQuest 1031796920.

- ^ "Novelty at the Stadium.: Mr. Hadley and Orchestra Delight Audience With "Semiramis"". The New York Times. August 6, 1926. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ "A Solid Year of "Broadway"". The New York Times. September 18, 1927. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 102; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 28.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (September 16, 1926). "Broadway – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"Broadway (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1926)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ "' Broadway' to Move to Century on Jan. 16: Reinhardt to Take His Players From Century to Smaller Theatre on Dec. 31 for Intimate Play". The New York Times. December 16, 1927. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (January 16, 1928). "The Merchant of Venice – Broadway Play – 1928 Revival". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"The Merchant of Venice (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1928)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ Atkinson, J. Brooks (January 17, 1928). "The Play; George Arliss as Shylock". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b Bloom 2007, p. 37; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 102; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 17.

- ^ Atkinson, J. Brooks (October 11, 1928). "The Play; Pugilism to Music". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (October 10, 1928). "Hold Everything – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"Hold Everything (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1928)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ a b The Broadway League (October 9, 1929). "June Moon – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"June Moon (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1929)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ Atkinson, J. Brooks (February 11, 1931). "The Play". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 102; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 29.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (February 10, 1931). "America's Sweetheart – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"America's Sweetheart (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1931)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ "Broadhurst for Shuberts; Aarons & Freedley to Give Up Theatre Lease in August". The New York Times. March 21, 1931. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (November 5, 1931). "Hamlet – Broadway Play – 1931 Revival". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"Hamlet (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1931)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ a b The Broadway League (January 12, 1932). "The Animal Kingdom – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"The Animal Kingdom (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1932)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ Allen, Kelcey (January 13, 1932). "'The Animal Kingdom' Crisp Barry Comedy: Leslie Howard Heads Capable Cast In Engrossing Play At The Broadhurst Marked By Clever Situations". Women's Wear Daily. Vol. 44, no. 8. p. 18. ProQuest 1676819616.

- ^ a b Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 103; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 29.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (September 8, 1932). "The Man Who Reclaimed His Head – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"The Man Who Reclaimed His Head (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1932)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ a b c Bloom 2007, p. 38; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 103; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 17.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (December 29, 1932). "Twentieth Century – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"Twentieth Century (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1932)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ Atkinson, Brooks (December 30, 1932). "In Which Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur Fire a Squib at the Theatre of Broadway". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (September 26, 1933). "Men in White – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"Men in White (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1933)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ "Group Theater Finds Success Embarrassing: 'Men in White' Playerg Almost Regard All-Season Run as an Affliction". New York Herald Tribune. June 17, 1934. p. D4. ProQuest 1114837891.

- ^ a b Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 103; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, pp. 29–30.

- ^ "Stage: Civic Repertory Goes Up to Broadway; Prices Up, Too". Newsweek. Vol. 4, no. 24. December 15, 1934. p. 18. ProQuest 1797097197.

- ^ "News of the Stage; ' L'Aiglon,' a Major Event, This Evening at the Broadhurst – Sundry Other Items". The New York Times. November 3, 1934. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (November 3, 1934). "L'Aiglon – Broadway Play – 1934 Revival". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"L'Aiglon (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1934)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ a b The Broadway League (January 7, 1935). "The Petrified Forest – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"The Petrified Forest (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1935)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ Atkinson, Brooks (January 8, 1935). "Leslie Howard in Robert Sherwood's Melodrama -Judith Anderson and Helen Menken in 'The Old Maid.'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ Atkinson, Brooks (December 27, 1935). "Helen Hayes in Housman's 'Victoria Regina' – Return of Lucienne Boyer in 'Varieties.'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (December 26, 1935). "Victoria Regina – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"Victoria Regina (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1935)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ ""Lady Precious Stream" to Tour". New York Herald Tribune. June 17, 1936. p. 14. ProQuest 1237407141.

- ^ a b Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 103; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 30.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (December 27, 1937). "A Doll's House – Broadway Play – 1937 Revival". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"A Doll's House (Broadway, Morosco Theatre, 1937)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ a b The Broadway League (January 11, 1939). "Dear Octopus – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"Dear Octopus (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1939)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ Atkinson, Brooks (January 12, 1939). "The Play; On Their Golden Wedding Day in Dodie Smith's 'Dear Octopus'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 103; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 31.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (March 23, 1939). "The Hot Mikado – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"The Hot Mikado (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1939)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ Atkinson, Brooks (March 24, 1939). "The Play; Bill Robinson Tapping Out the Title Role in 'The Hot Mikado' at the Broadhurst Theatre". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (June 19, 1939). "Streets of Paris – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

"The Streets of Paris (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1939)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022. - ^ Bloom 2007, p. 38; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 103.

- ^ The Broadway League (October 1, 1940). "Boys and Girls Together – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

"Boys and Girls Together (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1940)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022. - ^ Atkinson, Brooks (October 2, 1940). "The Play; Ed Wynn Appears in 'Boys and Girls Together' With Jane Pickens, Dave Apollon and the De Marcos". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (October 31, 1941). "High Kickers – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

"High Kickers (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1941)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022. - ^ Atkinson, Brooks (November 1, 1941). "George Jessel and Sophie Tucker in a Musical Comedy About Show Business, 'High Kickers'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (May 20, 1942). "Uncle Harry – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

"Uncle Harry (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1942)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022. - ^ L.n (May 21, 1942). "Murder Mystery, 'Uncle Harry,' Has Premiere at Broadhurst – Joseph Schildkraut and Eva Le Gallienne Are Starred". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c Bloom 2007, p. 38; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 104; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 18.

- ^ The Broadway League (June 17, 1943). "Early to Bed – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

"Early to Bed (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1943)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022. - ^ a b c d Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 104; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 32.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (June 27, 1944). "Ten Little Indians – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"Ten Little Indians (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1944)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ Zolotow, Sam (June 27, 1944). "Christie Thriller Arriving Tonight; 'Ten Little Indians,' Dealing With Eight Murders, Will Open at Broadhurst". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (April 8, 1944). "Follow the Girls – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"Follow the Girls (Broadway, New Century Theatre, 1944)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ The Broadway League (March 7, 1946). "Three to Make Ready – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

"Three to Make Ready (Broadway, George Abbott Theatre, 1946)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022. - ^ Calta, Louis (October 31, 1946). "'Happy Birthday' Arrivals Tonight; Anita Loos Comedy, Starring Helen Hayes, Will Open at the Broadhurst Theatre". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (October 31, 1946). "Happy Birthday – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"Happy Birthday (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1946)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 104; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, pp. 32–33.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 33.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (May 18, 1950). "The Liar – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"The Liar (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1950)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ a b c Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 104; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 33.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (March 10, 1951). "Romeo and Juliet – Broadway Play – 1951 Revival". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

"Romeo and Juliet (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1951)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022. - ^ a b The Broadway League (May 14, 1951). "Flahooley – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

"Flahooley (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1951)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022. - ^ "News of the Theater: Flahooley' Closing". New York Herald Tribune. June 8, 1951. p. 16. ProQuest 1318533747.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (June 21, 1951). "Seventeen – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

"Seventeen (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1951)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022. - ^ a b Bloom 2007, p. 38; Botto & Mitchell 2002, pp. 104–105; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 18.

- ^ Calta, Louis (January 3, 1952). "Pal Joey' Returns to Rialto Tonight; Musical to Open at Broadhurst, With Vivienne Segal, Harold Lang as Its Co-stars". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 105; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 34.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (January 3, 1952). "Pal Joey – Broadway Musical – 1952 Revival". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"Pal Joey (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1952)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022. - ^ Bracker, Milton (November 20, 1953). "Spaniards Offer 'Don Juan Tenorio': Theatre Troupe Gives Zorrilla Work at the Broadhurst – Ulloa Acts and Directs". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ The Broadway League (December 16, 1953). "The Prescott Proposals – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

"The Prescott Proposals (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1953)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022. - ^ a b c Bloom 2007, p. 38; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 105; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 18.

- ^ Zolotow, Sam (October 31, 1956). "Premiere Tonight for 'Auntie Mame'; Lawrence and Lee Comedy Starring Rosalind Russell to Be at the Broadhurst Road Agency Planned". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 18.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (October 31, 1956). "Auntie Mame – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

"Auntie Mame (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1956)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2022. - ^ Atkinson, Brooks (October 11, 1958). "Theatre: 'Suzie Wong'; Adaptation of Novel at the Broadhurst". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 105; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 35.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (October 14, 1958). "The World of Suzie Wong – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

"The World of Suzie Wong (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1958)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2022. - ^ Atkinson, Brooks (November 24, 1959). "Theatre: Little Flower Blooms Again; 'Fiorello!' Begins Run at the Broadhurst". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (November 23, 1959). "Fiorello! – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

"Fiorello! (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1959)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2022. - ^ Calta, Louis (May 4, 1961). "'Fiorello!' Prices to Be Cut Tuesday; Reduction Slated With Move to the Broadway Theatre". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ Taubman, Howard (October 4, 1961). "Theatre: Noel Coward at the Helm; His 'Sail Away' Opens at the Broadhurst". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ Chapman, John (October 4, 1961). "Noel Coward's 'Sail Away' Has Cheerful Air and Elaine Stritch". Daily News. p. 597. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (October 3, 1961). "Sail Away – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

"Sail Away (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1961)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2022. - ^ Calta, Louis (February 16, 1962). "New Home Found by 'My Fair Lady'; Hit Musical to Begin at the Broadhurst on Feb. 28 Wilder Approves Plan 'Great Day' Listed 'Caretaker' to Close". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (March 15, 1956). "My Fair Lady – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

"My Fair Lady (Broadway, Times Square Church, 1956)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2022. - ^ a b c Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 106; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 35.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (March 15, 1962). "No Strings – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

"No Strings (Broadway, George Abbott Theatre, 1962)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2022. - ^ Taubman, Howard (October 25, 1963). "Theater: '110 in the Shade'; Musical 'Rainmaker' Is at Broadhurst". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (October 24, 1963). "110 in the Shade – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

"110 in the Shade (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1963)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2022. - ^ a b The Broadway League (September 30, 1964). "Oh What a Lovely War – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

"Oh What a Lovely War (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1964)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2022. - ^ Zolotow, Sam (February 9, 1965). "$650,000 'Kelly' Lasts One Night; Joseph E. Levine Principal Loser on Musical". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (February 6, 1965). "Kelly – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

"Kelly (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1965)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2022. - ^ a b Bloom 2007, p. 38; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 106; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 18.

- ^ Taubman, Howard (April 26, 1965). "The Theater: 'Half a Sixpence' Opens; Musical of H.G. Wells's 'Kipps' at Broadhurst Engaging Hero Played by Tommy Steele". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (April 25, 1965). "Half a Sixpence – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

"Half a Sixpence (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1965)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2022. - ^ Kerr, Walter (November 21, 1966). "The Theater: 'Cabaret' Opens at the Broadhurst; Musical by Masteroff, Kander and Ebb Lotte Lenya Stars Directed by Prince". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 106; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 36.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (November 20, 1966). "Cabaret – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

"Cabaret (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1966)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2022. - ^ Chapman, John (November 1, 1967). "Ingrid Bergman is Back on Stage in Eugene O'Neill's Last Big Play". Daily News. p. 958. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ Barnes, Clive (November 1, 1967). "Theater: O'Neill's 'More Stately Mansions' Opens; Ingrid Bergman, Miss Dewhurst and Hill Star Quintero's Completion of Play at Broadhurst". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (October 31, 1967). "More Stately Mansions – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

"More Stately Mansions (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1967)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2022. - ^ a b The Broadway League (March 13, 1967). "You Know I Can't Hear You When the Water's Running – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

"You Know I Can't Hear You When the Water's Running (Broadway, Ambassador Theatre, 1967)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2022. - ^ "'I Can't Hear You' Changes". The New York Times. November 14, 1968. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (January 2, 1969). "The Fig Leaves Are Falling – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

"The Fig Leaves Are Falling (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1969)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2022. - ^ a b The Broadway League (February 12, 1969). "Play It Again, Sam – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

"Play It Again, Sam (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1969)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2022. - ^ Barnes, Clive (February 13, 1969). "Theater: Woody Allen in Fantasyland; 'Play It Again, Sam' Is on Broadhurst Stage Stand-Up Comic Stars in His Own Comedy". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 106.

- ^ a b c Bloom 2007, p. 38; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 106; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 37.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (November 14, 1971). "Twigs – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

"Twigs (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1971)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022. - ^ Barnes, Clive (November 15, 1971). "Theater: Four 'Twigs' Make a Nest". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (February 14, 1972). "Grease – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

"Grease (Broadway, Eden Theatre, 1972)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022. - ^ a b Buckley, Tom (December 7, 1979). "'Grease' Breaks a Record on Broadway". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (December 20, 1972). "The Sunshine Boys – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

"The Sunshine Boys (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1972)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022. - ^ Kerr, Walter (December 31, 1972). "News of the Rialto". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (April 7, 1974). "Thieves – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

"Thieves (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1974)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022. - ^ Barnes, Clive (April 8, 1974). "Theater: Touches of Urban Poetry". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 106; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 38.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (November 12, 1974). "Sherlock Holmes – Broadway Play – 1974 Revival". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

"Sherlock Holmes (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1974)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022. - ^ Pointer, Michael (November 10, 1974). "Holmes (Hooray!) Will Foil Moriarty (Hiss!) Once Again!". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (February 3, 1976). "A Matter of Gravity – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

"A Matter of Gravity (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1976)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022. - ^ Barnes, Clive (February 4, 1976). "Hepburn Is Center of "Gravity"". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ Bloom 2007, p. 38; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 106; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 38.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (June 22, 1976). "Godspell – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

"Godspell (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1976)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022. - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 38.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (September 21, 1976). "A Texas Trilogy: Lu Ann Hampton Laverty Oberlander – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

"A Texas Trilogy (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1976)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022. - ^ Barnes, Clive (September 24, 1976). "Stage: The Last Of 'Texas Trilogy'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ Botto & Mitchell 2002, pp. 106–107; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 38.

- ^ Barnes, Clive (December 15, 1976). "Stage: 'Sly Fox,' A Tireless Farce". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (December 14, 1976). "Sly Fox – Broadway Play – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

"Sly Fox (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1976)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022. - ^ "'Sly Fox' Closing Sunday After 495 Performances". The New York Times. February 15, 1978. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ Eder, Richard (March 28, 1978). "'Dancin',' Fosses's Musical, Opens at the Broadhurst". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ^ Wallach, Allen (March 28, 1978). "Theater: Fosse's "Dancin'" kicks up its heels". Newsday. p. 120. ISSN 2574-5298. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 107; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 38.

- ^ a b The Broadway League (March 27, 1978). "Dancin' – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

"Dancin' (Broadway, Broadhurst Theatre, 1978)". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 30, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2022. - ^ a b c Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 107.

- ^ Watt, Douglas (December 18, 1980). "'Amadeus' questions the gift of genius". Daily News. p. 673. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ^ Rich, Frank (December 18, 1980).

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch