Burr (novel)

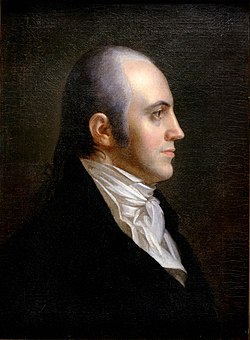

Cover of the first edition | |

| Author | Gore Vidal |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Series | Narratives of Empire |

| Genre | Historical novel |

| Publisher | Random House |

Publication date | 1973 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 430 pp |

| ISBN | 0-394-48024-4 |

| OCLC | 658914 |

| 813/.5/4 | |

| LC Class | PZ3.V6668 Bu |

| Followed by | Lincoln (novel) |

Burr: A Novel is a 1973 historical novel by Gore Vidal that challenges the traditional Founding Fathers iconography of United States history, by means of a narrative that includes a fictional memoir by Aaron Burr, in representing the people, politics, and events of the U.S. in the early 19th century.[1] It was a finalist for the National Book Award in 1974.

Burr is chronologically the first book of the seven-novel series Narratives of Empire, with which Vidal examined, explored, and explained the imperial history of the United States; chronologically, the six other historical novels of the series are Lincoln (1984), 1876 (1976), Empire (1987), Hollywood (1990), Washington, D.C. (1967), and The Golden Age (2000).[2]

Description

[edit]

Burr portrays the eponymous anti-hero as a fascinating and honorable gentleman, and portrays his contemporary opponents as mortal men; thus, George Washington is an incompetent military officer, a general who lost most of his battles; Thomas Jefferson is a fey, especially dark and pedantic hypocrite who schemed and bribed witnesses in support of a false charge of treason against Burr, to whom he almost lost in the 1800 United States presidential election; and Alexander Hamilton is a bastard-born, over-ambitious opportunist whose rise was by General Washington's hand, until being fatally wounded in the 1804 Burr–Hamilton duel.

The enmities were established when, despite Burr's initial victory in the voting, the presidential election of 1800 was a tied vote in the Electoral College, between him and Thomas Jefferson. To break the tied electoral vote, the House of Representatives—dominated by Alexander Hamilton—voted thirty-six times, until they elected Jefferson, and by procedural default named Burr as the vice president.[3]

The contemporary story of political intrigue occurs from 1833 to 1840, in the time of Jacksonian democracy, years after the treason trial. The narrator is Charles Schermerhorn Schuyler, an ambitious young man working as a law clerk in Aaron Burr's New York City law firm. Charlie Schuyler is not from a politically-connected family, and is ambivalent about politics and about how law is practiced. Hesitant about taking the examination for admission to the bar, Schuyler works as a newspaper reporter while dreaming of becoming a successful writer so that he can emigrate to Europe.

Important to the intrigues of the plotters are the allegation that Vice President Martin Van Buren is the bastard son of Aaron Burr; the veracity or falsity of that allegation; and its usefulness in high-government politics. Because Van Buren is a strong candidate for the 1836 United States presidential election, his political enemies, especially newspaper publisher William Leggett, enlist Schuyler to glean personally embarrassing facts about Van Buren from the aged Burr, a septuagenarian in 1834.

Tempted with the promise of money, Schuyler considers authoring a pamphlet "proving" that Vice President Van Buren is Burr's son, which will end Van Buren's career. He becomes torn between honoring Burr, whom he admires, and betraying Burr for the cash that will enable him to take the woman he loves to Europe. At story's end, Schuyler has learned more than he expected about Burr, Van Buren, and his own character.[4]

As in the novels Messiah (1954), Julian (1964), and Creation (1981), the colonial people, their times, and the places of Burr (1973) are presented through the memoirs of a character in the tale. Throughout the story, the narrative presents thematic parallels to The Memoirs of Aaron Burr (1837), co-written with Matthew Livingston Davis.[5] Many of the incidents in Burr are historical: Thomas Jefferson was a slaver who fathered children with some of his slave women; the Continental Army General James Wilkinson was a double agent for the Kingdom of Spain; Alexander Hamilton regularly was challenged to duels; and Aaron Burr was tried for and acquitted of treason, consequent to the Burr Plot (1807).[6]

In the "Afterword" to Burr, Vidal states that, in most instances, the actions and words of the historical characters represented are based upon their personal documents and historical records.[7] Moreover, besides challenging the traditionalist, mythical iconography of the Founding Fathers of the United States, the most controversial aspect of the novel Burr is the unsubstantiated claim that Alexander Hamilton gossiped about Burr and his daughter, Theodosia, practicing incest—which character assassination supposedly led to their duel; killing Hamilton ended the public life of Aaron Burr.[8]

Narrative frame

[edit]The novel comprises two storylines. One gives us Charles Schuyler's personal and professional perspectives on early mid-19th-century New York, and his coming to know the titular character Aaron Burr in his later, quieter years. The other gives us, by means of Burr's recollections as read and recorded by Schuyler, his experience of late eighteenth century British colonial life and the independence struggle or "Revolution" (in the section called 1833); and most substantially, his experience of life in post-Independence New York and his participation in the political development of the American Republic (through the main section of the novel, 1834), thus:

- 1834

- Chapter Ten: Memoirs of Aaron Burr — One

- Chapter Eleven: Memoirs of Aaron Burr — Two

- Chapter Twelve: Memoirs of Aaron Burr — Three, and Memoirs of Aaron Burr — Four

- Chapter Thirteen: Memoirs of Aaron Burr — Five

- Chapter Fourteen: Memoirs of Aaron Burr — Six

- Chapter Fifteen: Memoirs of Aaron Burr — Seven

- Chapter Eighteen: Memoirs of Aaron Burr — Eight, and Memoirs of Aaron Burr — Nine

- Chapter Nineteen: Memoirs of Aaron Burr — Ten

- Chapter Twenty: Memoirs of Aaron Burr — Eleven

- Chapter Twenty-one: Memoirs of Aaron Burr — Twelve

- Chapter Twenty-five: Memoirs of Aaron Burr — Thirteen

- Chapter Twenty-seven: Memoirs of Aaron Burr — Fourteen

- Chapter Twenty-eight: Memoirs of Aaron Burr — Fifteen

- Chapter Thirty-two: Memoirs of Aaron Burr — Sixteen

- Chapter Thirty-four: Memoirs of Aaron Burr — Seventeen

- Chapter Thirty-six: Memoirs of Aaron Burr — Eighteen

- 1835

- Chapter Two: Memoirs of Aaron Burr — Nineteen

- Chapter Five: Memoirs of Aaron Burr — Twenty

- Chapter Seven: Memoirs of Aaron Burr — Twenty-one

List of characters

[edit]Vidal notes in the novel's afterword that each character named therein "actually existed,"[9] with the exception of its narrator, Charlie Schuyler, and William de la Touche Clancey, a thinly veiled satire of longtime Vidal critic William F. Buckley Jr.[10] The sections of the novel that deal with the narrator's activity in the 1830s (as opposed to Burr's reminiscences of his adventures in the American Revolution through his trial for treason) focus on the political life of New York City during the end of the administration of President Andrew Jackson. This list of characters includes those that appear or are mentioned in the novel by its narrator, in order of appearance or mention.

- Charles Schuyler - Law clerk in Aaron Burr's law office, narrator

- Aaron Burr - New York City attorney, former Vice President

- Eliza Jumel - Burr's second wife; reputed to be the richest woman in New York City

- Dr. Bogart - Elderly friend of Burr

- Nelson Chase - Burr's law clerk, married to Mary Eliza Chase

- Mary Eliza Chase - Niece of (rumored to be daughter of) Eliza Jumel

- William Legget - Subeditor of Evening Post

- William Cullen Bryant - Assistant Editor of Evening Post, poet

- Martin Van Buren - Vice President of the United States under President Andrew Jackson

- Henry Clay - Senator, candidate for President (mentioned)

- Richard Johnson - Senator from Kentucky, potential reform candidate for President (mentioned)

- Mr. Craft - Burr's law office clerk

- Matthew L. Davis - Editor, Tammany Hall insider, Burr's official biographer

- Sam Swartwout - Collector of the Port of New York, appointed by President Jackson

- Rosanna Townsend - Madam

- Helen Jewett - Prostitute

- Aaron Columbus Burr - Burr's illegitimate son, silversmith

- Edwin Forrest - Actor

- William de la Touche Clancy - Publisher of The American

- Edmund Simpson - Owner of the Park Theater (mentioned)

- Tom Hamblin - Manager of the Bowery Theater (mentioned)

- Ephraim [No Last Name] - Ferryman, son of Burr's Revolutionary War comrade

- James Madison - Former President of the United States, friend of Burr (mentioned)

- John Marshall - Former Chief Justice of the United States, presiding judge in Burr's treason trial, cousin of Thomas Jefferson (mentioned)

- Washington Irving - Novelist and journalist, acquaintance of Burr

- Gulian Verplanck - Anti-Tammany mayoral candidate for New York CIty

- Fitz-Greene Halleck - Poet, secretary to John Jacob Astor

- John Jacob Astor - Financier

- Mordecai Noah - Former Sheriff of New York City

- Thomas Skidmore - Proto-socialist reformer

- Charles Baldwin - Glutton

- Alexander Hamilton Jr. - Lawyer, son of Burr's rival (mentioned)

- Edward Livingston - Congressman

- Reverend Peter Williams - Pastor of African Episcopal Church on Centre Street, NYC

- Arthur and Lewis Tappan - Abolitionist leaders

- Mrs. Redman - Boardinghouse proprietress

- Reginald Gower - Printer and bookstore owner

- Mrs. Keese (formerly Mrs. Overton) - Burr's landlady

- Robert Wright - Philadelphia publisher of Davy Crockett

- Colonel Davy Crockett - Congressman from Tennessee

- George Orson Fuller - Phrenologist

- Richard Robinson - Male prostitute, accused murderer

- John Ogden Edwards - Judge, Burr's cousin

- Pantaleone - Butler at American Consulate in Amalfi

- Donna Carolina de Traxler - Wife of Charles Schuyler

Reception

[edit]In his review for The New York Times, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt lauded the novel as a "a tour de force of historical imagination", praising the plot as a "clever piece of machinery" whilst noting the "rather far-fetched and clumsy denouement". Writing in the same publication, George Dangerfield took issue with Vidal's heavy use of historical details, opining the novel "is far, far better when it is simply being a fantasy".[11][12]

Kirkus Reviews praised the novel as "a clever book", noting the timeliness of its iconoclastic treatment of certain Founding Fathers "considering our mood of national discontent" amid the then-ongoing Watergate scandal.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ "Burr Summary - eNotes.com". eNotes. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ Vidal, Gore. (2006) Point to Point Navigation: A Memoir, 1964 to 2000, p. 123.

- ^ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition (1993) p. 401.

- ^ Burr (Magill’s Survey of American Literature, Revised Edition)

- ^ Aaron Burr, Matthew Livingston Davis, Memoirs of Aaron Burr, Volume 1, 1837.

- ^ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition (1993) p. 401.

- ^ Vidal, Gore. Burr (1973), p. 429–30

- ^ Burr (Magill’s Survey of American Literature, Revised Edition)

- ^ Vidal, Gore. Burr (1973), p. 429

- ^ "Gore Vidal. INSCRIBED. 1876, A Novel. New York: Random House, [1976]. First edition, first printing". Heritage Auctions.

- ^ Lehmann-Haupt, Christopher (October 25, 1973). "Back to the First Principals". The New York Times. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- ^ Dangerfield, George (October 28, 1973). "Less than history and less than fiction". The New York Times. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- ^ "Burr". Kirkus Reviews. November 1, 1973. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch