Carrosserie Pourtout

Carrosserie Pourtout was a French coachbuilding company. Founded by Marcel Pourtout in 1925, the firm is best known for its work in the decades prior to World War II, when it created distinctive and prestigious bodies for cars from numerous European manufacturers. Pre-war Pourtout bodies were mainly one-off, bespoke creations, typically aerodynamic and sporting in character. Together with chief coach designer and stylist Georges Paulin from 1933 to 1938, Pourtout pioneered the Paulin invented 'Eclipse' retractable hardtop system on four models of Peugeot, several Lancia Belna's and other car makes.

Among the company's customers was Georges Clemenceau, the physician and journalist who served as the prime minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and 1917 to 1920.[1]

The firm later turned to designs for industry and public transport.

Carrosserie Pourtout ceased its creative operations in 1994 but survives to the present day as a vehicle body repair shop.

Before and during World War II

[edit]

Marcel Pourtout started in 1925 with a small workshop in Bougival and a workforce of twelve. His wife Henriette looked after the firm’s finances. Hard work and plentiful orders allowed repayment of Carrosserie Pourtout’s start-up loans in just a few years, and in 1928 the premises were enlarged.

In 1936 Pourtout expanded again, taking over the Hurtu factory workshops in Rueil-Malmaison. Here the staff, which then numbered fifteen, could produce small production runs of coachwork, in addition to the one-offs.

Until World War II, Carrosserie Pourtout's creations were exhibited at the annual Salon de l'Automobile de Paris.

At the beginning of the war, before France fell to the Germans, the firm made ambulances on Chevrolet chassis.

In 1941 Marcel Pourtout was appointed Mayor of Rueil-Malmaison (Hauts-de-Seine) in 1941, as it was customary at the time to choose someone who headed a business. (He held the post until 1944; and again from 1947 to 1971.)

In 1942 the occupying forces requisitioned Pourtout's workshops, partially demolishing them when they left. Also in 1942 the Nazis executed the firm's prewar designer, Georges Paulin (see below), as a member of the French Resistance and an agent of British Intelligence.

Collaboration with Emile Darl'mat and Georges Paulin

[edit]

At the end of 1933 Peugeot’s Paris concessionaire Emile Darl'mat introduced Marcel Pourtout to Georges Paulin, a dentist with a flair for coachwork design. He became Pourtout’s lead designer.

Richard Adatto, author of a book on French aerodynamic styling of the era,[2] has been quoted as saying: "Paulin became the leading French stylist of the time...Everything he touched was designed with aerodynamics in mind. He was very conscious of fuel efficiencies and the aerodynamic efficiencies that could be created by the lines of the car. You could go faster, which meant you could put a smaller engine in the car and it could go faster even though it was a small car."[3]

Pourtout, Darl'mat and Paulin collaborated in the creation of the revolutionary Eclipse roof, a design of retractable hardtop that had a special mechanism, patented in Paulin's name, to stow it out of sight in the car’s boot.[4] Carrosserie Pourtout produced Eclipse versions of the Peugeot 301, 401, 402 and 601, the Lancia Belna, and models from Hotchkiss and Panhard.

For the 1937 24 Hours of Le Mans endurance race Carrosserie Pourtout collaborated with Emile Darl'Mat to create the bodies for three identical cars that utilized modified Peugeot 402 engines in modified 302 chassis. In the 1937 race The Darl'mat Roadsters placed 7th, 8th and 10th overall. They returned the following year, and the entry driven by De Cortanze won the under-2 litre class.

In 1937 and 1938 Carrosserie Pourtout made a road-going version of the Le Mans cars, the Peugeot 402 Darl’Mat "Spécial Sport", which had a total production run of 106.

Major prewar works

[edit]

DELAGE

| Type | Dates | Quantity |

|---|---|---|

| Types unidentified | 1927 to 1939 | 5 |

| D1 12 | January 1937 to November 1937 | 3 |

| D6 60 | January 1937 | 1 |

| D 6 70 | January 1937 to October 1938 | 31 |

| D 6 75 | Oct. 1938 to Sept. 1940 | 21 |

| D 8 120 | October 1937 to October 1938 | 3 |

LANCIA

| Type | Dates | Quantity |

|---|---|---|

| Dilambda | September 1931 | 2 |

| Belna | December 1934 to April 1937 | 326 (including 209 convertibles) |

| Ardennes | September 1937 to July 1939 | 36 |

| Astura | March 1939 | 1 |

PEUGEOT 402 Darl'mat

| Type | Dates | Quantity |

|---|---|---|

| Roadster | September 1936 to June 1939 | 54 |

| Cabriolet | September 1937 to June 1939 | 32 |

| Coupé | June 1937 to August 1938 | 20 |

RENAULT Saprar

| Type | Dates | Quantity |

|---|---|---|

| Primaquatre Sport Roadster | September 1938 to June 1939 | 10 |

| Primaquatre Sport Cabriolet | March 1939 to July 1939 | 15 |

| Primaquatre Sport Coach | October 1938 | 1 |

After World War II

[edit]Notwithstanding the loss of Paulin, Carrosserie Pourtout continued to exhibit at the Salon de l'Automobile from 1947 to 1952, and the firm produced a number of prestigious bodies before Marcel Pourtout and his son Claude turned to projects for industry and advertising.

Altogether, taking into account the firm's work both before and after World War II, Carrosserie Pourtout designed and built bodies on chassis from at least twenty manufacturers, namely: Voisin, Fiat, Hispano-Suiza, Panhard, Hotchkiss, Bugatti, Lorraine, Lancia, Unic, Renault, Peugeot, Bentley, Delage, Delahaye, Buick, Delaunay-Belleville, Talbot-Lago, Healey, Simca and Chrysler.

Gallery of Pourtout-bodied cars

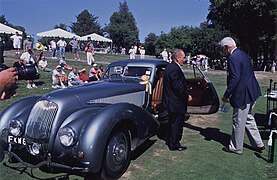

[edit]- 1938 "Embiricos" Bentley

- 1938 "Embiricos" Bentley

- 1946 Delahaye 135 MS

- Bugatti

- Chevrolet ambulance attended by Pourtout's son Claude

- 1932 Delage

- Delahaye, Bois de Boulogne

- 1948 Delahaye 135

- 1948 Delahaye 135M

- Delahaye 135 MS

- 1929 Fiat 509 Coupé Royal

- 1927 Georges Irat Model A

- c.1930 Hispano-Suiza

- 1933 Hispano-Suiza J12

- 1936 Hispano-Suiza

- Hotchkiss

- Lancia

- Lancia

- 1935 Lancia Belna

- Lancia Belna

- :Lancia Belna Roadster and Eclipse

- Panhard

- c.1930 Panhard

- 1934 Panhard Eclipse

- Peugeot 12 CV

- Peugeot 302 Darl'mat

- Peugeot 401 Eclipse, Champs Elysées

- 1938 Peugeot 402 Darl'mat "Spécial Sport"

- Peugeot 402 Darl'mat Le Mans

- Peugeot 601D Eclipse

- Peugeot 601DL Eclipse

- 1939 Talbot-Lago T150C-SS coupé

References

[edit]- ^ "Coachbuilders: Pourtout", Coachbuild webmagazine. Extensive Pourtout gallery also on the same site. Archived 2017-04-10 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on July 2, 2008.

- ^ Adatto, Richard S, 2003. "From Passion to Perfection: The Story of French Streamlined Styling 1930 - 1939", SPE Barthélémy Archived 2011-10-12 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 2-912838-22-3, reviewed at Auto History Online. Retrieved on July 2, 2008.

- ^ Buchanan, James. "The Story of Lancia, Paulin and John Moir", redroom.com Archived 2011-07-26 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on July 2, 2008.

- ^ Sass, Rob (10 December 2006). "New Again: The Hideaway Hardtop". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2015-10-29. Retrieved 2021-03-31.

- ^ Automobilia n°14, juin 1997

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch