Cavalcade (play)

Cavalcade is a play by Noël Coward with songs by Coward and others. It focuses on three decades in the life of the Marryots, an upper-middle-class British family, and their servants, beginning in 1900 and ending in 1930, a year before the premiere. It is set against major historical events of the period, including the Relief of Mafeking; the death of Queen Victoria; the sinking of the RMS Titanic; and World War I. The popular songs at the time of each event were interwoven into the score.

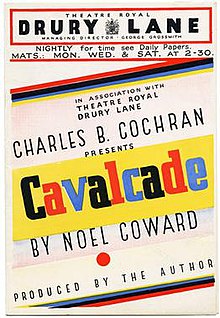

The play was premiered in London in 1931 at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, directed by the author. The spectacular production presented by the impresario Charles B. Cochran, involved a huge cast and massive sets. The play was very successful and ran for almost a year. It took advantage of the large stage of the Drury Lane Theatre with its hydraulics and moving components to dramatise the events.

Background and production

[edit]During the run of his successful comedy Private Lives in London in 1930, Coward discussed with the impresario C. B. Cochran the idea of a large, spectacular production to follow the intimate Private Lives. He considered the idea of an epic set in the French revolution, but in an old copy of the Illustrated London News he saw a photograph of a troopship leaving for the Boer War, which gave him the idea for the new play. He outlined his scenario to Cochran and asked him to secure the Coliseum, London's largest theatre. Cochran was unable to do so, but was able to book the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, which was not much smaller,[1] provided Coward could guarantee an approximate opening date.[2] Coward and his designer Gladys Calthrop inspected Drury Lane and found it adequate in terms of the size of its stage and its technical facilities, although two extra hydraulic lifts had to be installed for quick changes of scenery, and unlike the Coliseum it lacked the revolving stage Coward wanted.[2][3] While Calthrop began designing hundreds of costumes and twenty-two sets, Coward worked on the script, which he completed in August 1931.[4]

Rehearsals began the following month.[5] With four hundred cast and crew members involved in the production, Coward divided the crowd into groups of twenty and assigned each a leader. Because remembering individual names would be impossible, everyone was given a colour and number for easy identification, thus allowing Coward to direct "Number 7 red" to cross downstage and shake hands with "Number 15 yellow and black". Extras were encouraged to create their own bits of stage business, as long as it did not draw attention from the main action of the scene.[6]

Cavalcade premiered on 13 October 1931, starring Mary Clare and Edward Sinclair as the Marryot parents and featuring John Mills, Binnie Barnes, Una O'Connor, Moya Nugent, Arthur Macrae, Irene Browne and Maidie Andrews in supporting roles. Despite a brief delay caused by a mechanical problem early in the first act, the performance was a strong success, and the play went on to become one of the year's biggest West End hits, running for 405 performances. The play closed in September 1932.

Original cast

[edit]- Jane Marryot – Mary Clare

- Robert Marryot – Edward Sinclair

- Ellen Bridges – Una O'Connor

- Alfred Bridges – Fred Groves

- Margaret Harris – Irene Browne

- Edith Harris – Alison Leggatt

- Edward Marryot – Arthur Macrae

- Joe Marryot – John Mills

- Fanny Bridges – Binnie Barnes

- Edith (as a child) – Veronica Vanderlyn

- Edward (as a child) – Peter Vokes

- Joe (as a child) – Leslie Flack

- Fanny (as a child) – Dorothy Keefe

- Laura Marsden (Mirabelle) – Strella Wilson

- Henry Charteris (Lieutenant Edgar) – Eric Puneur

- Rose Darling (Ada) – Maidie Andrews

- Nicky Banks (Tom Jolly) – Billy Fry

- Cook – Laura Smithson

- Annie – Merle Tottenham

- Mrs Snapper – Edie Martin

- Flo Grainger – Dorothy Monkman

- George Grainger – Bobby Blythe

- Daisy Devon – Moya Nugent

- Marion Christie – Betty Hare

- Netta Lake – Phyllis Harding

- Connie Crawshay – Betty Shale

- Tim Bateman – Philip Clarke

- Douglas Finn – John Beerbohm

- Lord Martlett – Anthony Pelissier

- Uncle Harry – Aly Ford

- Uncle George – Charles Wingrove

- Uncle Dick – Walter Rayland

- Uncle Jack – Tod Squires

- Uncle Bob – Tom Carlisle

- Uncle Jim – William McGuigan

- Freda Weddell – Lena Brand

- Olive Frost – Marcelle Turner

- Gladys (Parlourmaid) – Dorothy Drover

- A communist – Anthony Blair

- A religious fanatic – Enid Clinton-Baddeley

- A wireless announcer – W. A. H. Harrison

- Pianist at night club – Jack London

- Trumpeter at night club – Leslie Thompson

Crowds, Soldiers, Sailors, Guests, etc.

Synopsis

[edit]Part I

[edit]Scene 1: Sunday 31 December 1899. The drawing-room of a London House

[edit]It is nearly midnight. Robert and Jane Marryot are seeing in the New Year quietly together in their London house. Their happiness is clouded by the Boer War: Jane's brother is besieged in Mafeking, and Robert himself will shortly be going to South Africa. Robert and Jane invited their butler, Bridges, and his wife, Ellen, to join them. Bells, shouting, and sirens outside usher in the New Year, and Robert proposes a toast to 1900. Hearing her two boys stirring upstairs, Jane runs up to see after them, and her husband calls to her to bring them down to join the adults.

Scene 2: Saturday 27 January 1900. A dockside

[edit]A month later, a contingent of volunteers are leaving for the war. On the dockside Jane and Ellen are seeing off Robert and Bridges. As the men go aboard, Jane comforts Ellen, who is crying. A band strikes up "Soldiers of the Queen". The volunteers wave their farewells to the cheering crowd.

Scene 3: Friday 8 March 1900. The drawing-room of the Marryots' house

[edit]The Marryot boys, Edward, aged twelve, and Joe, aged eight, are playing soldiers with a young friend, Edith Harris. She objects to being made to play "the Boers", and they begin to quarrel. The noise brings in their mothers. Joe throws a toy at Edith, and is sharply slapped by Jane, whose nerves are on edge with anxiety about her brother and her husband. Her state of mind is not helped by a barrel-organ outside, playing "Soldiers of the Queen" under the window. Margaret, Edith's mother, sends the organ-grinder away and proposes to take Jane to the theatre to take her mind off her worry.

Scene 4: Friday 8 May 1900. A theatre

[edit]Jane and Margaret are in a stage-box, watching MirabeIle, the currently popular musical comedy. The plot is the usual froth, but the denouement is not reached: the theatre manager comes onstage to announce that Mafeking has been relieved. Joyous uproar breaks out; the audience claps and cheers and some begin to sing "Auld Lang Syne".

Scene 5: Monday 21 January 1901. The kitchen of the Marryots' house

[edit]The cook, Annie the parlourmaid, and Ellen's mother Mrs Snapper are preparing a special tea to greet Bridges on his return from the war. He comes in with Ellen, looking well, and kisses his little baby, Fanny. He tells them that he has bought a public house so that he and Ellen can work for themselves in future. The celebratory mood is dampened when Annie brings in a newspaper reporting that Queen Victoria is dying.

Scene 6: Sunday 27 January 1901. Kensington Gardens

[edit]This scene is all in mime. Robert and Jane are walking in Kensington Gardens with their children when they meet Margaret and Edith Harris. Everyone is in black, solemn and silent, following the Queen's death.

Scene 7: Saturday 2 February 1901. The Marryots' drawing-room

[edit]On the balcony, Jane, Margaret, their children and the servants are watching Queen Victoria's funeral procession. Robert, who was awarded the Victoria Cross is walking in the procession, and Jane has some difficulty in making her boys suppress their excitement and pay due respect as the coffin passes. As the lights fade, Joe comments, "She must have been a very little lady ".

Scene 8: Thursday 14 May 1903. The grand staircase of a London house

[edit]Jane and Robert are attending a grand ball given by the Duchess of Churt. The Major-domo announces, "Sir Robert and Lady Marryot".

Part II

[edit]Scene I: Saturday 16 June 1906. The bar parlour of a London public house

[edit]Jane has brought her son Edward, now eighteen, to see Ellen in the flat above the public house. They have just finished tea, together with Flo and George, relations of the Bridges. Seven-year-old Fanny has been dancing to entertain them. Bridges enters, clearly drunk. Jane, dismayed, makes a tactful departure. Bridges starts to bully Fanny and is ejected from the room by George and Flo.

Scene 2: Saturday 16 June 1906. A London street (exterior of the public house)

[edit]After emerging from the pub, Bridges carries on up the road. He is knocked down and killed by a car.

Scene 3: Wednesday 10 March 1909. The private room of a London restaurant

[edit]Edward Marryot is holding his twenty-first birthday party, with many smart young guests. Rose, an actress from the old Mirabelle production, proposes his health and sings the big waltz number from the show.

Scene 4: Monday 25 July 1910. The beach of a popular seaside resort

[edit]A concert party of six "Uncles" is performing in a bandstand. Ellen and her family are there and Fanny wins a prize for a song and dance competition. They unexpectedly meet Margaret, Jane and Joe. Ellen tells them that she has kept on the pub since her husband's death and that Fanny is now at a dancing-school and determined to go on the stage.

Scene 5: Sunday 14 April 1912. The deck of an Atlantic liner

[edit]Edward has married Edith Harris, and they are on their honeymoon. They speculate blithely how long the initial bliss of marriage will last. As they walk off, she lifts her cloak from where it has been draped on the ship rail, revealing the name Titanic on a lifebelt. The lights fade into complete darkness; the orchestra plays "Nearer, My God, to Thee" very quietly.

Scene 6: Tuesday 4 August 1914. The Marryots' drawing-room

[edit]War has been declared. Robert and Joe are keen to join the army. Jane is horrified, and refuses to indulge in the jingoism she sees around her.

Scene 7: 1914–1915–1916–1917–1918. Marching

[edit]Soldiers are seen endlessly marching. The orchestra plays songs of the First World War.

Scene 8: Tuesday 22 October 1918. A restaurant

[edit]Joe and Fanny – now a rising young actress – are dining in a West End restaurant. Joe is in army officer's uniform. He is on leave but is about to return to the Front. They discuss marriage, but she envisages opposition from his family, and bids him wait until he is back from the war for good.

Scene 9: Tuesday 22 October 1918. A railway station

[edit]Jane sees Joe off at the railway station. Like many of the women on the platform she is distressed.

Scene 10: Monday 11 November 1918. The Marryots' drawing-room

[edit]Ellen visits Jane, having found out that Joe is emotionally involved with her daughter. The two mothers fall out: Ellen thinks Jane regards Fanny as beneath Joe socially. As Ellen is leaving, the maid brings in a telegram. Jane opens it and tells Ellen. "You needn't worry about Fanny and Joe any more, Ellen. He won't be able to come back at all, because he's dead."

Scene 11: Monday 11 November 1918. Trafalgar Square

[edit]Surrounded by the frantic revelry of Armistice Night, Jane is walking, dazed, through Trafalgar Square. With tears streaming down her face, she cheers wildly and waves a rattle, while the band plays "Land of Hope and Glory ".

Part III

[edit]Scene 1: Tuesday 31 December 1929. The Marryot's drawing room

[edit]Margaret and Jane, both now elderly, are sitting by the fire. Margaret leaves, after wishing a happy New Year to Jane and Robert, who has come in to drink a New Year toast with his wife. Jane drinks first to him and then to England: "The hope that one day this country of ours, which we love so much, will find dignity and greatness, and peace again".

Scene 2: Evening, 1930. A night club

[edit]Robert, Jane, Margaret, Ellen, and the full company are in a night club. At the piano, Fanny sings "Twentieth Century Blues", and after the song everyone dances.

Scene 3: Chaos

[edit]The lights fade, and a chaotic succession of images representative of life in 1929 is spotlighted. When the noise and confusion reach a climax the stage suddenly fades into darkness and silence. At the back a Union Jack glows through the darkness. The scene ends with the lights coming up on the massed company singing "God Save the King".

Revivals and adaptations

[edit]The play was first revived in the West End in 1966, at the Scala Theatre, with a cast of 96 drama students from the Rose Bruford College. The reviewer in The Times found Coward's work remained "dazzling and durable".[7] The first professional revival was in 1981 at the Redgrave Theatre in Farnham in a production directed by David Horlock and with a cast of 12 professional actors and 300 amateur performers. That production was filmed by the BBC and shown in 1982 as a two-part documentary, Cavalcade – A Backstage Story.[8] In 1995 a production starring Gabrielle Drake and Jeremy Clyde as Jane and Robert Maryott played at Sadler's Wells Theatre, London and on tour.[9] The Citizens Theatre, Glasgow, presented the play in 1999, in a production by Philip Prowse.[10]

A film adaptation in 1933 won three Academy Awards, including "Best Picture".[11] C. A. Lejeune called it "the best British film that has ever been made", and expressed exasperation that British studios had not taken the play up instead of allowing it to go to Hollywood.[12][n 1] Cavalcade was adapted for BBC radio by Val Gielgud and Felix Felton and broadcast three times in 1936.[13] A 1970s television series, Upstairs, Downstairs, was to some extent based on the play.[14]

Reception

[edit]Opening just before the British General Election, the play's strongly patriotic themes were credited by the Conservative Party for helping them secure a large percentage of the middle class votes, despite the fact Coward had conceived the project a full year before the election was held, and strenuously denied having any thought of influencing its outcome.[15][n 2] King George V and Queen Mary attended the performance on election night and received Coward in the Royal Box during the second interval.[17] In The Daily Mail for 1 November 1931, Alan Parsons wrote:

When the curtain fell last night at Drury Lane on Mr Noel Coward's Cavalcade, there was an ovation such as I have not heard in very many years' playgoing. Mr Coward, after returning thanks to all concerned, said: "After all, it is a pretty exciting thing in these days to be English". And therein lies the whole secret of Cavalcade—it is a magnificent play in which the note of national pride pervading every scene and every sentence must make each one of us face the future with courage and high hopes.[18]

Reviewing the 1999 revival, Michael Billington wrote that it displayed the contradictory elements in Coward's writings, a show "traditionally seen as a patriotic pageant about the first 30 years of the century" but strongly anti-militaristic and portraying "the anger that bubbles away among the working class". He concluded, "Cavalcade is actually about the way the high hopes at the start of the century have turned to senseless slaughter and hectic hedonism".[19]

Music

[edit]A record with the title Cavalcade Suite was made by the New Mayfair Orchestra. It contained a selection of the contemporary songs used in Cavalcade, introduced by Coward. At the end he speaks the toast to England from the play. (HMV C2289)

Coward himself recorded "Lover of My Dreams" (the Mirabelle Waltz Song), with, on the reverse, "Twentieth Century Blues", played by the New Mayfair Novelty Orchestra, with vocal by an unnamed singer identified by Mander and Mitchenson as Al Bowlly. (HMV B4001)

Cavalcade—Vocal Medley: On this Coward sings "Soldiers of the Queen", "Goodbye, Dolly", "Lover of My Dreams", "I do Like to be Beside the Seside", "Goodbye, My Bluebell", "Alexander's Ragtime Band", "Everybody's Doing It", "Let's All Go Down the Strand", "If You were the Only Girl", "Take Me Back to Dear Old Blighty", "There's a Long, Long Trail", "Keep the Home Fires Burning", and "Twentieth Century Blues". (HMV C2431).

Coward later recorded "Twentieth Century Blues" on the LP album "Noël Coward in New York", with an orchestra conducted by Peter Matz. (Columbia ML 5163)

Notes, references and sources

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Why must a couple of dozen British artists go half across the world to make a film of British life under a British director from a play by a British dramatist?"[12]

- ^ "I was … congratulated upon my uncanny shrewdness in slapping on a strong patriotic play two weeks before a General Election, which was bound to result in a sweeping Conservative majority. (Here I must regretfully admit that during rehearsals I was so very much occupied in the theatre and, as usual, so bleakly uninterested in politics that I had not the remotest idea, until a few days before production, that there was going to be an election at all! However, there was, and its effect on the box office was considerable.)"[16]

References

[edit]- ^ Herbert, p. 1354

- ^ a b Mander and Mitchenson, pp. 166–1567

- ^ Coward, p. 233

- ^ Lesley, p. 159; and Morley (1974), p. 208

- ^ Coward, p. 235

- ^ Morley (1974), p. 209

- ^ "Students' skill in Coward play", The Times, 15 July 1966, p. 20

- ^ "Cavalcade – A Backstage Story", BBC Genome. Retrieved 21 January 2019

- ^ Church, Michael. "Theatre", The Independent, 21 August 1995

- ^ Cooper, Nell. "Theatre", The Times, 6 December 1999, p. 43

- ^ Kinn and Piazza, p. 31

- ^ a b Lejeune, C. A. "The Pictures", The Observer, 19 February 1933

- ^ Noel Coward's "Cavalcade", The Manchester Guardian, 27 June 1936; and "Revival of Noel Coward's 'Cavalcade'", The Manchester Guardian, 8 October 1936, p. 2

- ^ Morley (1999), p. xii

- ^ Coward, p. 241

- ^ Coward, quoted in Mander and Michenson, p. 167

- ^ Macpherson, p. 200

- ^ Quoted in Mander and Mitchenson, p. 165

- ^ Billington, Michael. "Oh what a ghastly war", The Guardian, 30 November 1999

Sources

[edit]- Coward, Noël (1992) [1937]. Autobiography. London: Mandarin. ISBN 978-0-7493-1413-2.

- Herbert, Ian (1977). Who's Who in the Theatre (sixteenth ed.). London: Pitman. ISBN 978-0-273-00163-8.

- Kinn, Gail; Jim Piazza (2008). The Academy Awards: The Complete Unofficial History. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal. ISBN 978-1-57912-772-5.

- Lesley, Cole (1976). The Life of Noël Coward. London: Cape. ISBN 978-0-224-01288-1.

- Mander, Raymond; Joe Mitchenson (1957). Theatrical Companion to Coward. London: Rockliff. OCLC 470106222.

- Macpherson, Ben (2018). Cultural Identity in British Musical Theatre, 1890–1939. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-59807-3.

- Morley, Sheridan (1974). A Talent to Amuse: A Biography of Noël Coward (second ed.). Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-003863-7.

- Morley, Sheridan (1999) [1994]. "Introduction". Noël Coward: Plays 3. London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-413-46100-1.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch