Jean-François Champollion

Jean-François Champollion | |

|---|---|

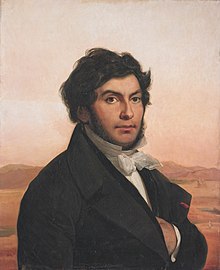

Jean-François Champollion, by Léon Cogniet | |

| Born | 23 December 1790 Figeac, France |

| Died | 4 March 1832 (aged 41) Paris, France |

| Alma mater | Collège de France Institut national des langues et civilisations orientales |

| Known for | Decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs |

| Spouse | Rosine Blanc (m. 1818) |

| Children | 1 |

| Relatives | Jacques Joseph Champollion-Figeac (brother) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Egyptian hieroglyphs |

Jean-François Champollion (French: [ʒɑ̃ fʁɑ̃swa ʃɑ̃pɔljɔ̃]), also known as Champollion le jeune ('the Younger'; 23 December 1790 – 4 March 1832), was a French philologist and orientalist, known primarily as the decipherer of Egyptian hieroglyphs and a founding figure in the field of Egyptology. Partially raised by his brother, the scholar Jacques Joseph Champollion-Figeac, Champollion was a child prodigy in philology, giving his first public paper on the decipherment of Demotic in his late teens. As a young man he was renowned in scientific circles, and read Coptic, Ancient Greek, Latin, Hebrew and Arabic.

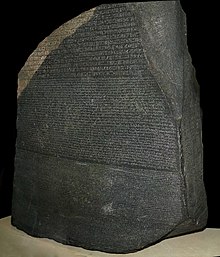

During the early 19th century, French culture experienced a period of 'Egyptomania', brought on by Napoleon's discoveries in Egypt during his campaign there (1798–1801), which also brought to light the trilingual Rosetta Stone. Scholars debated the age of Egyptian civilization and the function and nature of the hieroglyphic script, which language if any it recorded, and the degree to which the signs were phonetic (representing speech sounds) or ideographic (recording semantic concepts directly). Many thought that the script was used only for sacred and ritual functions, and that as such it was unlikely to be decipherable since it was tied to esoteric and philosophical ideas, and did not record historical information. The significance of Champollion's decipherment was that he showed these assumptions to be wrong, and made it possible to begin to retrieve many kinds of information recorded by the ancient Egyptians.

Champollion lived in a period of political turmoil in France, which continuously threatened to disrupt his research in various ways. During the Napoleonic Wars, he was able to avoid conscription, but his Napoleonic allegiances meant that he was considered suspect by the subsequent Royalist regime. His own actions, sometimes brash and reckless, did not help his case. His relations with important political and scientific figures of the time, such as Joseph Fourier and Silvestre de Sacy, helped him, although in some periods he lived exiled from the scientific community.

In 1820, Champollion embarked in earnest on the project of the decipherment of hieroglyphic script, soon overshadowing the achievements of British polymath Thomas Young, who had made the first advances in decipherment before 1819. In 1822, Champollion published his first breakthrough in the decipherment of the Rosetta hieroglyphs, showing that the Egyptian writing system was a combination of phonetic and ideographic signs – the first such script discovered. In 1824, he published a Précis in which he detailed a decipherment of the hieroglyphic script demonstrating the values of its phonetic and ideographic signs. In 1829, he travelled to Egypt where he was able to read many hieroglyphic texts that had never before been studied and brought home a large body of new drawings of hieroglyphic inscriptions. Home again, he was given a professorship in Egyptology but lectured only a few times before his health, ruined by the hardships of the Egyptian journey, forced him to give up teaching. He died in Paris in 1832, 41 years old. His grammar of Ancient Egyptian was published posthumously under the supervision of his brother.

During his life as well as long after his death, intense discussions over the merits of his decipherment were carried out among Egyptologists. Some faulted him for not having given sufficient credit to the early discoveries of Young, accusing him of plagiarism, and others long disputed the accuracy of his decipherments. However, subsequent findings and confirmations of his readings by scholars building on his results gradually led to the general acceptance of his work. Although some still argue that he should have acknowledged the contributions of Young, his decipherment is now universally accepted and has been the basis for all further developments in the field. Consequently, he is regarded as the "Founder and Father of Egyptology".[1]

Biography

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]

Jean-François Champollion was born on 23 December 1790, the last of seven children (two of whom had died earlier). He was raised in humble circumstances; his father Jacques Champollion was a book trader from Valjouffrey near Grenoble who had settled in the small town of Figeac in the Department of Lot.[2] His father was a notorious drunk,[3] and his mother, Jeanne-Françoise Gualieu, seems to have been largely an absent figure in the life of young Champollion, who was mostly raised by his older brother Jacques-Joseph. One biographer, Andrew Robinson, even speculated that Champollion was not in fact the son of Jacques Champollion's wife but the result of an extramarital affair.[4]

Towards the end of March 1801, Jean-François left Figeac for Grenoble, which he reached on 27 March, and where Jacques-Joseph lived in a two-room flat on the rue Neuve. Jacques-Joseph was then working as an assistant in the import-export company Chatel, Champollion and Rif,[5] yet taught his brother to read, and supported his education.[5] His brother also may have been part of the source of Champollion's interest in Egypt, since as a young man he wanted to join Napoleon's Egyptian expedition, and often regretted not being able to go.

Often known as the younger brother of better known Jacques-Joseph, Jean-François was often called Champollion le Jeune (the young). Later when his brother became the more famous of the two, Jacques added the town of his birth as a second surname and hence is often referred to as Champollion-Figeac, in contrast to his brother Champollion. Although studious and largely self-educated, Jacques did not have Jean-François' genius for language; however, he was talented at earning a living and supported Jean-François for most of his life.[6]

Given the difficulty of the task of educating his brother while earning a living, Jacques-Joseph decided to send his younger brother to the well-regarded school of the Abbé Dussert in November 1802,[7] where Champollion stayed until the summer of 1804. During this period, his gift for languages first became evident: he started out learning Latin and Greek, but quickly progressed to Hebrew and other Semitic languages such as Ethiopic,[8] Arabic, Syriac and Chaldean.[9] It was while a student here that he took up an interest in Ancient Egypt, likely encouraged in this direction by Dussert and his brother, both orientalists.[7]

At the age of 11, he came to the attention of the prefect of Grenoble, Joseph Fourier, who had accompanied Napoleon Bonaparte on the Egyptian expedition that had discovered the Rosetta Stone. An accomplished scholar in addition to a well-known mathematical physicist, Fourier had been entrusted by Napoleon with the publication of the results of the expedition in the monumental series of publications titled Description de l'Égypte. One biographer has stated that Fourier invited the 11-year-old Champollion to his home and showed him his collection of Ancient Egyptian artefacts and documents. Champollion was enthralled, and upon seeing the hieroglyphs and hearing that they were unintelligible, he declared that he would be the one to succeed in reading them.[10] Whether or not the report of this visit is true, Fourier did go on to become one of Champollion's most important allies and supporters and surely had an important role in instilling his interest in Ancient Egypt.[10]

From a young age, Champollion showed great interest in the Coptic language, rightly believing it to be the last stage of development of the ancient Egyptian language, and the key to deciphering the hieroglyphs. He frequented a Coptic priest living in Paris, called Youhanna Chiftichi, who taught him to read and speak Coptic fluently. In a letter written to his brother, Champollion wrote of Chiftichi stating:

- "I am going to visit a Coptic priest at Saint-Roch, rue Saint-Honoré, who celebrates Mass [...] who will instruct me in Coptic names, and the pronunciation of Coptic letters. I am devoting myself entirely to the Coptic language, for I want to know the Egyptian language as well as my own native French. My great work on the Egyptian papyri will be based on this [ancient] tongue."[11][12][13]

- "My Coptic language is going well, I am very happy. Imagine my pleasure in speaking the language of my dear Amenhotep III, Seti, Ramses and Thutmose! [...] I will meet with a Coptic priest named Chiftichi at the Saint-Roch Church to learn more about Coptic names and letter pronunciation."[14]

From 1804, Champollion studied at a lycée in Grenoble but hated its strict curriculum, which only allowed him to study oriental languages one day per week, and he begged his brother to move him to a different school. Nonetheless, at the lycée he took up the study of Coptic, which would become his main linguistic interest for years to come and prove crucial in his approach to decipherment of the hieroglyphs.[15] He had a chance to practice his Coptic when he met Dom Raphaël de Monachis, a former Egyptian Christian monk of Syrian origin and Arabic translator to Napoleon, who visited Grenoble in 1805.[16] Champollion became obsessed with the Coptic language as predecessor of the ancient Egyptian language that he wrote to his brother saying:

- "I dream in Coptic. I do nothing but that, I dream only in Coptic, in Egyptian [...] I am so Coptic, that for fun, I translate into Coptic everything that comes into my head. I speak Coptic all alone to myself, since no one else can understand me. This is the real way for me to put my pure Egyptian into my head."[17]

By 1806, Jacques-Joseph was making preparations to bring his younger brother to Paris to study at the University. Jean-François had by then already developed a strong interest in Ancient Egypt, as he wrote in a letter to his parents dated January 1806:[18]

- "I want to make a profound and continuous study of this ancient nation. The enthusiasm brought me by the study of their monuments, their power and knowledge filling me with admiration, all of this will grow further as I acquire new notions. Of all the people that I prefer, I shall say that none is as important to my heart as the Egyptians."

To continue his studies, Champollion wanted to go to Paris, Grenoble offering few possibilities for such specialized subjects as ancient languages. His brother thus stayed in Paris from August to September that same year, so as to seek his admission in a specialized school.[19] Around this time, he learned Classical Chinese, Avestan, Middle Persian, and the Persian language.[20] Before leaving however Champollion presented, on 1 September 1807, his Essay on the Geographical Description of Egypt before the Conquest of Cambyses before the Academy of Grenoble whose members were so impressed that they admitted him to the Academy six months later.[21]

From 1807 to 1809, Champollion studied in Paris, under Silvestre de Sacy, the first Frenchman to attempt to read the Rosetta stone, and with orientalist Louis-Mathieu Langlès, and with Raphaël de Monachis who was now in Paris. Here he perfected his Arabic and Persian, in addition to the languages that he had already acquired. He was so immersed in his studies that he took up the habit of dressing in Arab clothing and calling himself Al Seghir, the Arab translation of le jeune.[22] He divided his time between the College of France, the Special School of Oriental Languages, the National Library where his brother was a librarian and the Commission of Egypt, the institution in charge of publishing the findings of the Egyptian expedition.[23] In 1808, he first began studying the Rosetta stone, working from a copy made by the Abbé de Tersan. Working independently he was able to confirm some of the readings of the demotic previously made by Johan David Åkerblad in 1802,[24][25] finally identifying the Coptic equivalents of fifteen demotic signs present on the Rosetta stone.[1]

In 1810, he returned to Grenoble to take up a seat as joint professor of Ancient History at the newly reopened Grenoble University. His salary as an assistant professor at Grenoble was fixed at 750 francs, a quarter of the salary received by full professors.[26]

Never well off and struggling to make ends meet, he also suffered since youth from chronically bad health, including gout and tinnitus. His health first began to deteriorate during his time in Paris, where the dank climate and unsanitary environment did not agree with him.[27]

Political trouble during the Napoleonic Wars

[edit]

During the Napoleonic Wars, Champollion was a young bachelor and thus liable to compulsory military service, which would have put him in great danger due to the extremely high mortality of soldiers in Napoleon's armies. Through the assistance of his brother and the prefect of Grenoble Joseph Fourier, who was also an Egyptologist, he successfully avoided the draft by arguing that his work on deciphering the Egyptian script was too important to interrupt.[28] First sceptical of the Napoleonic regime, after the fall of Napoleon in 1813 and the institution of the royalist regime under Louis XVIII, Champollion came to consider the Napoleonic state the lesser of two evils. Anonymously he composed and circulated songs ridiculing and criticizing the royal regime – songs that became highly popular among the people of Grenoble.[29] In 1815, Napoleon Bonaparte escaped from his exile on Elba and landed with an army at the Côte d'Azur and marched directly on Grenoble where he was received as a liberator. Here he met with Champollion, whose many requests for exemption from the draft he remembered, and he asked him how his important work was progressing. Champollion replied, that he had just finished his Coptic grammar and dictionary. Napoleon requested that he send the manuscripts to Paris for publication. His brother Jacques joined the Napoleonic cause, putting both of the brothers in danger at the end of the Hundred Days when Napoleon was finally defeated, Grenoble being the last city to resist the royalist advances. In spite of the risk to themselves, having been put under Royalist surveillance, the Champollion brothers nonetheless aided the Napoleonic general Drouet d'Erlon who had been sentenced to death for his participation in the Battle of Waterloo, giving him shelter and helping him escape to Munich. The brothers were condemned to internal exile in Figeac, Champollion was removed from his university post in Grenoble and the faculty closed.[30]

Under the new Royalist regime, the Champollion brothers invested much of their time and efforts in establishing Lancaster schools, in an effort to provide the general population with education. This was considered a revolutionary undertaking by the Ultra-royalists, who did not believe that education should be made accessible for the lower classes.[31] In 1821, Champollion even led an uprising, in which he and a band of Grenobleans stormed the citadel and hoisted the tricolore instead of the Bourbon Royalist flag. He was charged with treason and went into hiding but was eventually pardoned.[32]

Family life

[edit]

In 1807, Champollion first declared his love for Pauline Berriat, sister of Jacques-Joseph's wife Zoé. His love was not reciprocated, so Champollion instead had an affair with a married woman named Louise Deschamps that lasted until around 1809. In 1811, Louise remarried; in 1813, Pauline died.[33]

It was around this time that Champollion met Rosine Blanc (1794–1871), whom he married in 1818, after four years of engagement. They had one daughter, Zoraïde Chéronnet-Champollion (1824–1889). Rosine was the daughter of a well-to-do family of Grenoblean glovemakers.[34] At first, her father did not approve of the match, since Champollion was a mere assistant professor when they first met, but with his increasing reputation, he eventually agreed. Originally, Jacques-Joseph was opposed to his brother's marriage, too, finding Rosine too dull-witted, and he did not attend the wedding, but later he grew fond of his sister-in-law. Although a happy family man, especially adoring his daughter, Champollion was frequently away for months or even years at a time, as he was travelling to Paris, to Italy, and to Egypt, while his family remained in Zoé and Jacques-Joseph's property in Vif, near Grenoble.[35] While in Livorno, Champollion developed an infatuation with an Italian poet, Angelica Palli. She presented an ode to Champollion's work at a celebration in his honour, and the two exchanged letters over the period 1826–1829 revealing the poor state of Champollion's marriage, yet an affair never developed.[36]

Deciphering the Egyptian hieroglyphs

[edit]

The Egyptian hieroglyphs had been well-known to scholars of the ancient world for centuries, but few had made any attempts to understand them. Many based their speculations about the script in the writings of Horapollon who considered the symbols to be ideographic, not representing any specific spoken language. Athanasius Kircher for example had stated that the hieroglyphs were symbols that "cannot be translated by words, but expressed only by marks, characters and figures", meaning that the script was in essence impossible to ever decipher. Others considered that the use of hieroglyphs in Egyptian society was limited to the religious sphere and that they represented esoteric concepts within a universe of religious meaning that was now lost.[37] But Kircher had been the first to suggest that modern Coptic was a degenerate form of the language found in the Egyptian demotic script,[38] and he had correctly suggested the phonetic value of one hieroglyph – that of mu, the Coptic word for water.[39] With the onset of Egyptomania in France in the early 19th century, scholars began approaching the question of the hieroglyphs with renewed interest, but still without a basic idea about whether the script was phonetic or ideographic, and whether the texts represented profane topics or sacred mysticism. This early work was mostly speculative, with no methodology for how to corroborate suggested readings. The first methodological advances were Joseph de Guignes' discovery that cartouches identified the names of rulers, and George Zoëga's compilation of a catalogue of hieroglyphs, and the discovery that the direction of reading depended on the direction in which the glyphs were facing.[40]

Early studies

[edit]Champollion's interest in Egyptian history and the hieroglyphic script developed at an early age. At the age of 16, he gave a lecture before the Grenoble Academy in which he argued that the language spoken by the ancient Egyptians, in which they wrote the Hieroglyphic texts, was closely related to Coptic. This view proved crucial in becoming able to read the texts, and the correctness of his proposed relation between Coptic and Ancient Egyptian has been confirmed by history. This enabled him to propose that the demotic script represented the Coptic language.[41]

Already in 1806, he wrote to his brother about his decision to become the one to decipher the Egyptian script:

"I want to make a profound and continuous study of this antique nation. The enthusiasm that brought me the study of their monuments, their power and knowledge filling me with admiration, all of this will grow further as I will acquire new notions. Of all the people that I prefer, I shall say that none is as important to my heart as the Egyptians."

— Champollion, 1806[42]

In 1808, Champollion received a scare when French archaeologist Alexandre Lenoir published the first of his four volumes on Nouvelles Explications des Hieroglyphes, making the young scholar fear that his budding work had already been surpassed. But he was relieved to find that Lenoir still operated under the assumption that the hieroglyphs were mystic symbols and not a literary system expressing language. This experience made him even more determined to be the first to decipher the language and he began dedicating himself even more to the study of Coptic, writing in 1809 to his brother: "I give myself up entirely to Coptic ... I wish to know Egyptian like my French, because on that language will be based my great work on the Egyptian papyri."[43] That same year, he was appointed to his first academic post, in history and politics at the University of Grenoble.[41]

In 1811, Champollion was embroiled in controversy, as Étienne Marc Quatremère, like Champollion a student of Silvestre de Sacy, published his Mémoires géographiques et historiques sur l'Égypte ... sur quelques contrées voisines. Champollion saw himself forced to publish as a stand-alone paper the "Introduction" to his work in progress L'Egypte sous les pharaons ou recherches sur la géographie, la langue, les écritures et l'histoire de l'Egypte avant l'invasion de Cambyse (1814). Because of the similarities in the topic matter, and the fact that Champollion's work was published after Quatremère's, allegations arose that Champollion had plagiarized the work of Quatremère. Even Silvestre de Sacy, the mentor of both authors, considered the possibility, to Champollion's great chagrin.[44]

Rivalry with Thomas Young

[edit]

| |||||||||||||||

| Ptolemy in hieroglyphs | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Era: Old Kingdom (2686–2181 BC) | |||||||||||||||

British polymath Thomas Young was one of the first to attempt decipherment of the Egyptian hieroglyphs, basing his own work on the investigations of Swedish diplomat Johan David Åkerblad. Young and Champollion first became aware of each other's work in 1814 when Champollion wrote to the Royal Society of which Young was the secretary, requesting better transcriptions of the Rosetta stone, to Young's irritation, arrogantly implying that he would be able to quickly decipher the script if he only had better copies. Young had at that time spent several months working unsuccessfully on the Rosetta text using Åkerblad's decipherments. In 1815, Young replied in the negative, arguing that the French transcriptions were equally good as the British ones, and added: "I do not doubt that the collective efforts of savants, such as M. Åkerblad and yourself, Monsieur, who have so much deepened the study of the Coptic language, might have already succeeded in giving a more perfect translation than my own, which is drawn almost entirely from a very laborious comparison of its different parts and with the Greek translation."[45] This was the first Champollion had heard of Young's research, and realizing that he also had a competitor in London was not to Champollion's liking.[45]

In his work on the Rosetta stone, Young proceeded mathematically without identifying the language of the text. For example, comparing the number of times a word appeared in the Greek text with the Egyptian text, he was able to point out which glyphs spelt the word "king", but he was unable to read the word. Using Åkerblad's decipherment of the demotic letters p and t, he realized that there were phonetic elements in the writing of the name Ptolemy. He correctly read the signs for p, t, m, i, and s, but rejected several other signs as "inessential" and misread others, due to the lack of a systematic approach. Young called the Demotic script "enchorial", and resented Champollion's term "demotic" considering it bad form that he had invented a new name for it instead of using Young's. Young corresponded with Sacy, now no longer Champollion's mentor but his rival, who advised Young not to share his work with Champollion and described Champollion as a charlatan. Consequently, for several years Young kept key texts from Champollion and shared little of his data and notes.[46]

When Champollion submitted his Coptic grammar and dictionary for publication in 1815, it was blocked by Silvestre de Sacy, who in addition to his personal animosity and envy towards Champollion also resented his Napoleonic affinities.[47] During his exile in Figeac, Champollion spent his time revising the grammar and doing local archaeological work, being for a time cut off from being able to continue his research.[48]

In 1817, Champollion read a review of his "Égypte sous les pharaons", published by an anonymous Englishman, which was largely favourable and encouraged Champollion to return to his former research.[49] Champollion's biographers have suggested that the review was written by Young, who often published anonymously, but Robinson, who wrote biographies of both Young and Champollion, considers it unlikely since Young elsewhere had been highly critical of that particular work.[50] Soon Champollion returned to Grenoble to seek employment again at the university, which was in the process of reopening the faculty of Philosophy and Letters. He succeeded, obtaining a chair in history and geography,[41] and used his time to visit the Egyptian collections in Italian museums.[41] Nonetheless, most of his time in the following years was consumed by his teaching work.[51]

Meanwhile, Young kept working on the Rosetta stone, and in 1819, he published a major article on "Egypt" in the Encyclopædia Britannica claiming that he had discovered the principle behind the script. He had correctly identified only a small number of phonetic values for glyphs but also made some eighty approximations of correspondences between Hieroglyphic and demotic.[42] Young had also correctly identified several logographs, and the grammatical principle of pluralization, distinguishing correctly between the singular, dual and plural forms of nouns. Young nonetheless considered the hieroglyphic, linear or cursive hieroglyphs (which he called hieratic) and a third script that he called epistolographic or enchorial, to belong to different historical periods and to represent different evolutionary stages of the script with increasing phoneticism. He failed to distinguish between hieratic and demotic, considering them a single script. Young was also able to identify correctly the hieroglyphic form of the name of Ptolemy V, whose name had been identified by Åkerblad in the demotic script only. Nonetheless, he assigned the correct phonetic values to only some of the signs in the name, incorrectly dismissing one glyph, the one for o, as unnecessary, and assigning partially correct values to the signs for m, l, and s. He also read the name of Berenice, but he managed to correctly identify only the letter n. Young was furthermore convinced that only in the late period had some foreign names been written entirely in phonetic signs, whereas he believed that native Egyptian names and all texts from the earlier period were written in ideographic signs. Several scholars have suggested that Young's true contribution to Egyptology was his decipherment of the Demotic script, in which he made the first major advances, correctly identifying it as being composed of both ideographic and phonetic signs.[52] Nevertheless, for some reason Young never considered that the same might be the case with the hieroglyphs.[53]

Later, the British Egyptologist Sir Peter Le Page Renouf summed up Young's method: "He worked mechanically, like the schoolboy who finding in a translation that Arma virumque means 'Arms and the man,' reads Arma 'arms,' virum 'and' , que 'the man.' He is sometimes right, but very much oftener wrong, and no one is able to distinguish between his right and his wrong results until the right method has been discovered."[54] Nonetheless, at the time it was clear that Young's work superseded everything Champollion had by then published on the script.[55]

Breakthrough

[edit]

Although dismissive of Young's work even before he had read it, Champollion obtained a copy of the Encyclopedia article. Even though he was suffering from failing health, and the chicanery of the Ultras kept him struggling to maintain his job, it motivated him to return in earnest to the study of the hieroglyphs. When he was eventually removed from his professorship by the Royalist faction, he finally had the time to work on it exclusively. While he awaited trial for treason, he produced a short manuscript, De l'écriture hiératique des anciens Égyptiens, in which he argued that the hieratic script was simply a modified form of hieroglyphic writing. Young had already anonymously published an argument to the same effect several years earlier in an obscure journal, but Champollion, having been cut off from academia, had probably not read it. In addition, Champollion made the fatal error of claiming that the hieratic script was entirely ideographic.[57] Champollion himself was never proud of this work and reportedly actively tried to suppress it by buying the copies and destroying them.[58]

These errors were finally corrected later that year when Champollion correctly identified the hieratic script as being based on the hieroglyphic script, but used exclusively on papyrus, whereas the hieroglyphic script was used on stone, and demotic used by the people.[59] Previously, it had been questioned whether the three scripts even represented the same language; and hieroglyphic had been considered a purely ideographic script, whereas hieratic and demotic were considered alphabetic. Young, in 1815, had been the first to suggest that the demotic was not alphabetic, but rather a mixture of "imitations of hieroglyphics" and "alphabetic" signs. Champollion, in contrast, correctly considered the scripts to coincide almost entirely, being in essence different formal versions of the same script.[60][58]

In the same year, he identified the hieroglyphic script on the Rosetta stone as being written in a mixture of ideograms and phonetic signs,[61] just as Young had argued for Demotic.[62] He reasoned that if the script was entirely ideographic the hieroglyphic text would require as many separate signs as there were separate words in the Greek text. But there were in fact fewer, suggesting that the script mixed ideographic and phonetic signs. This realization finally made it possible for him to detach himself from the idea that the different scripts had to be either fully ideographic or fully phonetic, and he recognized it as being a much more complex mixture of sign types. This realization gave him a distinct advantage.[63]

Names of rulers

[edit]Using the fact that it was known that the names of rulers appeared in cartouches, he focused on reading the names of rulers as Young had initially tried. Champollion managed to isolate a number of sound values for signs, by comparing the Greek and Hieroglyphic versions of the names of Ptolemy and Cleopatra – correcting Young's readings in several instances.[64]

In 1822 Champollion received transcriptions of the text on the recently discovered Philae obelisk, which enabled him to double-check his readings of the names Ptolemy and Cleopatra from the Rosetta stone. The name "Cleopatra" had already been identified on the Philae obelisk by William John Bankes, who scribbled the identification in the margin of the plate though without any actual reading of the individual glyphs. Young and others would later use the fact that the Cleopatra cartouche had been identified by Bankes to claim that Champollion had plagiarized his work. It remains unknown whether Champollion saw Bankes' margin note identifying the cartouche or whether he identified it by himself.[65] All in all, using this method he managed to determine the phonetic value of 12 signs (A, AI, E, K, L, M, O, P, R, S, and T). By applying these to the decipherment of further sounds he soon read dozens of other names.[66]

Astronomer Jean-Baptiste Biot published a proposed decipherment of the controversial Dendera zodiac, arguing that the small stars following certain signs referred to constellations.[67] Champollion published a response in the Revue encyclopédique, demonstrating that they were in fact grammatical signs, which he called "signs of the type", today called "determinatives". Young had identified the first determinative "divine female", but Champollion now identified several others.[68] He presented the progress before the academy where it was well received, and even his former mentor-turned-archenemy, de Sacy, praised it warmly, leading to a reconciliation between the two.[69]

| ||||

| Thutmose in hieroglyphs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

The main breakthrough in his decipherment was when he was also able to read the verb "MIS" related to birth, by comparing the Coptic verb for birth with the phonetic signs "MS" and the appearance of references to birthday celebrations in the Greek text. It was on 14 September 1822, while comparing his readings to a set of new texts from Abu Simbel, that he made the realization. Running down the street to find his brother, he yelled "Je tiens mon affaire!" (I've got it!) but collapsed from the excitement.[70][71] Champollion subsequently spent the short period from 14 to 22 September writing up his results.[72]

While the name Thutmose had also been identified (but not read) by Young, who realized that the first syllable was spelt with a depiction of an ibis representing Thoth, Champollion was able to read the phonetic spelling of the second part of the word and check it against the mentioning of births in the Rosetta stone.[Notes 1] This finally confirmed to Champollion that the ancient texts as well as the recent ones used the same writing system and that it was a system that mixed logographic and phonetic principles.[71]

Letter to Dacier

[edit]

A week later on 27 September 1822, he published some of his findings in his Lettre à M. Dacier, addressed to Bon-Joseph Dacier, secretary of the Paris Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. The handwritten letter was originally addressed to De Sacy, but Champollion crossed out the letter of his mentor turned adversary, substituting the name of Dacier, who had faithfully supported his efforts.[70] Champollion read the letter before the assembled Académie. All his main rivals and supporters were present at the reading, including Young who happened to be visiting Paris. This was the first meeting between the two. The presentation did not go into details regarding the script and in fact, was surprisingly cautious in its suggestions. Although he must have been already certain of this, Champollion merely suggested that the script was already phonetic from the earliest available texts, which would mean that the Egyptians had developed writing independently of the other civilizations around the Mediterranean. The paper also still contained confusions regarding the relative role of ideographic and phonetic signs, still arguing that also hieratic and demotic were primarily ideographic.[73]

Scholars have speculated that there had simply not been sufficient time between his breakthrough and collapse to fully incorporate the discovery into his thinking. But the paper presented many new phonetic readings of names of rulers, demonstrating clearly that he had made a major advance in deciphering the phonetic script. And it finally settled the question of the dating of the Dendera zodiac, by reading the cartouche that had been erroneously read as Arsinoë by Young, in its correct reading "autocrator" (Emperor in Greek).[74]

He was congratulated by the amazed audience including de Sacy and Young.[42] Young and Champollion became acquainted over the next days, Champollion sharing many of his notes with Young and inviting him to visit at his house, and the two parted on friendly terms.[75]

Reactions to the decipherment

[edit]At first, Young was appreciative of Champollion's success, writing in a letter to his friend that "If he [Champollion] did borrow an English key, the lock was so dreadfully rusty that no common arm would have had strength enough to turn it. ... .You will easily believe that were I ever so much the victim of the bad passions, I should feel nothing but exultation at Mr. Champollion's success: my life seems indeed to be lengthened by the accession of a junior coadjutor in my researches, and of a person too, who is so much more versed in the different dialects of the Egyptian language than myself."[76]

Nonetheless, the relationship between them quickly deteriorated, as Young began to feel that he was being denied due credit for his own "first steps" in the decipherment. Also, because of the tense political climate between England and France in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, there was little inclination to accept Champollion's decipherments as valid among the English. When Young later read the published copy of the lettre he was offended that he himself was mentioned only twice, and one of those times being harshly critiqued for his failure in deciphering the name "Berenice". Young was further disheartened because Champollion at no point recognized his work as having provided the platform from which decipherment had finally been reached. He grew increasingly angry with Champollion and shared his feelings with his friends who encouraged him to rebut with a new publication. When by a stroke of luck a Greek translation of a well-known demotic papyrus came into his possession later that year, he did not share that important finding with Champollion. In an anonymous review of the lettre, Young attributed the discovery of the hieratic as a form of hieroglyphs to de Sacy and described Champollion's decipherments merely as an extension of Åkerblad and Young's work. Champollion recognized that Young was the author, and sent him a rebuttal of the review while maintaining the charade of the anonymous review. Furthermore, Young, in his 1823 An Account of Some Recent Discoveries in Hieroglyphical Literature and Egyptian Antiquities, including the author's original alphabet, as extended by Mr. Champollion, he complained that "however Mr Champollion may have arrived at his conclusions, I admit them, with the greatest pleasure and gratitude, not by any means as superseding my system, but as fully confirming and extending it."(p. 146).[60]

In France, Champollion's success also produced enemies. Edmé-Francois Jomard was chief among them, and he spared no occasion to belittle Champollion's achievements behind his back, pointing out that Champollion had never been to Egypt and suggesting that really his lettre represented no major progress from Young's work. Jomard had been insulted by Champollion's demonstration of the young age of the Dendera zodiac, which he had himself proposed was as old as 15,000 years. This exact finding had also brought Champollion in the good graces of many priests of the Catholic Church who had been antagonized by the claims that Egyptian civilization might be older than their accepted chronology, according to which the earth was only 6,000 years old.[77]

Précis

[edit]Young's claims that the new decipherments were merely a corroboration of his own method, meant that Champollion would have to publish more of his data to make clear the degree to which his own progress built on a systematicity that was not found in Young's work. He realized that he would have to make it apparent to all that his was a total system of decipherment, whereas Young had merely deciphered a few words. Over the next year, he published a series of booklets about the Egyptian gods, including some decipherments of their names.[78]

Building on his progress, Champollion now began to study other texts in addition to the Rosetta stone, studying a series of much older inscriptions from Abu Simbel. During 1822, he succeeded in identifying the names of pharaohs Ramesses and Thutmose written in cartouches in these ancient texts. With the help of a new acquaintance, the Duke de Blacas in 1824, Champollion finally published the Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens dedicated to and funded by King Louis XVIII.[79] Here he presented the first correct translation of the hieroglyphs and the key to the Egyptian grammatical system.[42]

In the Précis, Champollion referred to Young's 1819 claim of having deciphered the script when he wrote that:

"A real discovery would have been to have really read the hieroglyphic name, that is, to have fixed the proper value to each of the characters it is composed of, and in such a manner, that these values were applicable everywhere that these characters appear

— [Précis, 1824, p. 22]"[42]

This task was exactly what Champollion set out to accomplish in the Précis, and the entire framing of the argument was as a rebuttal to M. le docteur Young and the translation in his 1819 article, which Champollion brushed off as "a conjectural translation".[80]

In the introduction, Champollion described his argument in points:

- That his "alphabet" (in the sense of phonetic readings) could be employed to read inscriptions from all of the periods of Egyptian history.

- That the discovery of the phonetic alphabet is the true key to understanding the entire hieroglyphic system.

- That the ancient Egyptians used the system in all of the periods of Egyptian history to represent the sounds of their spoken language phonetically.

- That all of the hieroglyphic texts are composed almost entirely of the phonetic signs that he had discovered.

Champollion never admitted any debt to Young's work,[60] although in 1828, a year before his death, Young was appointed to the French Academy of Sciences, with Champollion's support.[81]

The Précis, which comprised more than 450 ancient Egyptian words and hieroglyphics groupings,[1] cemented Champollion as having the main claim to the decipherment of the hieroglyphs. In 1825, his former teacher and enemy Silvestre de Sacy reviewed his work positively stating that it was already well "beyond the need for confirmation".[82] In the same year, Henry Salt put Champollion's decipherment to the test, successfully using it to read further inscriptions. He published a corroboration of Champollion's system, in which he also criticized Champollion for not acknowledging his dependence on Young's work.[83]

With his work on the Précis, Champollion realized that in order to advance further he needed more texts, and transcriptions of better quality. This caused him to spend the next years visiting collections and monuments in Italy, where he realized that many of the transcriptions from which he had been working had been inaccurate – hindering the decipherment; he made a point of making his own copies of as many texts as possible. During his time in Italy, he met the Pope, who congratulated him on having done a "great service to the Church", by which he was referring to the counterarguments he had provided against the challengers to the Biblical chronology. Champollion was ambivalent, but the Pope's support helped him in his efforts to secure funds for an expedition.[84]

Contribution to the decipherment of cuneiform

[edit]

The deciphering of the cuneiform script started with the first efforts at understanding Old Persian cuneiform in 1802, when Friedrich Münter realized that recurring groups of characters in Old Persian inscriptions must be the Old Persian word for "king" (𐎧𐏁𐎠𐎹𐎰𐎡𐎹, now known to be pronounced xšāyaθiya). Georg Friedrich Grotefend extended this work by realizing a king's name is often followed by "great king, king of kings" and the name of the king's father.[86][87] Through deductions, Grotefend was able to figure out the cuneiform characters that are part of Darius, Darius's father Hystaspes, and Darius's son Xerxes. Grotefend's contribution to Old Persian is unique in that he did not have comparisons between Old Persian and known languages, as opposed to the decipherment of the Egyptian hieroglyphics and the Rosetta Stone. All his decipherments were done by comparing the texts with known history.[87] Grotefend presented his deductions in 1802, but they were dismissed by the Academic community.[87]

It was only in 1823 that Grotefend's discovery was confirmed, when Champollion, who had just deciphered hieroglyphs, had the idea of trying to decrypt the quadrilingual hieroglyph-cuneiform inscription on a famous alabaster vase in the Cabinet des Médailles, the Caylus vase.[90][85][91][92] The Egyptian inscription on the vase turned out to be in the name of King Xerxes I, and the orientalist Antoine-Jean Saint-Martin, who accompanied Champollion, was able to confirm that the corresponding words in the cuneiform script (𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 𐏐 𐏋 𐏐 𐎺𐏀𐎼𐎣, Xšayāršā : XŠ : vazraka, "Xerxes : The Great King") were indeed the words that Grotefend had identified as meaning "king" and "Xerxes" through guesswork.[90][85][91] This was the first time the hypotheses of Grotefend could be vindicated. In effect, the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs was decisive in confirming the first steps of the decipherment of the cuneiform script.[91]

More advances were made in Grotefend's work and by 1847, most of the symbols were correctly identified. The decipherment of the Old Persian Cuneiform script was at the beginning of the decipherment of all the other cuneiform scripts, as various multi-lingual inscriptions between the various cuneiform scripts were obtained from archaeological discoveries.[87] The decipherment of Old Persian, the first cuneiform script to be deciphered, was then notably instrumental to the decipherment of Elamite and Babylonian thanks to the trilingual Behistun inscription, which ultimately led to the decipherment of Akkadian (predecessor of Babylonian) and then Sumerian, through the discovery of ancient Akkadian-Sumerian dictionaries.[93]

Confirmation of the antiquity of phonetical hieroglyphs

[edit]

Champollion had been confronted to the doubts of various scholars regarding the existence of phonetical hieroglyphs before the time of the Greeks and the Romans in Egypt, especially since Champollion had only proved his phonetic system on the basis of the names of Greek and Roman rulers found in hieroglyphs on Egyptian monuments.[95][96] Until his decipherment of the Caylus vase, he had not found any foreign names earlier than Alexander the Great that were transliterated through alphabetic hieroglyphs, which led to suspicions that they were invented at the time of the Greeks and Romans, and fostered doubts whether phonetical hieroglyphs could be applied to decipher the names of ancient Egyptian Pharaohs.[95][96] For the first time, here was a foreign name ("Xerxes the Great") transcribed phonetically with Egyptian hieroglyphs, already 150 years before Alexander the Great, thereby essentially proving Champollion's thesis.[95] In his Précis du système hiéroglyphique published in 1824, Champollion wrote of this discovery: "It has thus been proved that Egyptian hieroglyphs included phonetic signs, at least since 460 BC".[97]

Curator of the Egyptian Antiquities in the Louvre

[edit]

After his groundbreaking discoveries in 1822, Champollion made the acquaintance of Pierre Louis Jean Casimir Duc de Blacas, an antiquary who became his patron and managed to gain him the favour of the king. Thanks to this, in 1824, he travelled to Turin to inspect a collection of Egyptian materials assembled by Bernardino Drovetti, which King Charles X had purchased, cataloguing it. In Turin and Rome, he realized the necessity of seeing Egyptian monuments first-hand and began to make plans for an expedition to Egypt while collaborating with Tuscan scholars and the Archduke Leopold. In 1824, he became a correspondent of the Royal Institute of the Netherlands.[99]

Following his successes and after several months of negotiations and talks by Jacques-Joseph while he was still in Italy,[98] Champollion was finally appointed curator of the Egyptian collections of the Musée du Louvre in a decree of Charles X[100] dated to 15 May 1826.[41][98] The two Champollion brothers organised the Egyptian collection in four rooms on the first floor of the south side of the Cour Carrée.[98] The visitors entered this section of the Louvre via a first room devoted to the funerary world of the Egyptians, the second room presented artefacts relating to civilian life in Ancient Egypt, while the third and fourth rooms were devoted to more artefacts pertaining to mortuary activities and divinities.[98] To accompany these extensive works, Champollion organised the Egyptian collection methodologically into well-defined series and pushed his museologic work to the point of choosing the appearance of the stands and pedestals.[98]

Champollion's work in the Louvre, as well as his and his brother's efforts to acquire a larger collection of Egyptian artefacts, had a profound impact on the Louvre museum itself, the nature of which changed the Louvre from a place dedicated to the fine-arts – to a museum in the modern sense of the term, with important galleries devoted to the history of various civilisations.[98]

Franco-Tuscan Expedition

[edit]

In 1827, Ippolito Rosellini, who had first met Champollion during his 1826 stay in Florence, went to Paris for a year in order to improve his knowledge of the method of Champollion's system of decipherment. The two philologists decided to organize an expedition to Egypt to confirm the validity of the discovery. Headed by Champollion and assisted by Rosellini, his first disciple and great friend, the mission was known as the Franco-Tuscan Expedition and was made possible by the support of the grand-duke of Tuscany, Leopold II, and Charles X.[101] Champollion and his second-in-command Rossellini were joined on the expedition by Charles Lenormant, representing the French government, and a team of eleven Frenchmen including the Egyptologist and artist Nestor L'Hote and Italians including the artist Giuseppe Angelelli.[102]

In preparation for the expedition, Champollion wrote the French Consul General Bernardino Drovetti for advice on how to secure permission from the Egyptian Khedive and Ottoman Viceroy Muhammad Ali of Egypt. Drovetti had initiated his own business of exporting plundered Egyptian antiques and did not want Champollion meddling in his affairs. He sent a letter discouraging the expedition stating that the political situation was too unstable for the expedition to be advisable. The letter reached Jacques Joseph Champollion a few weeks before the expedition was scheduled to leave, but he conveniently delayed in sending it on to his brother until after the expedition had left.[103]

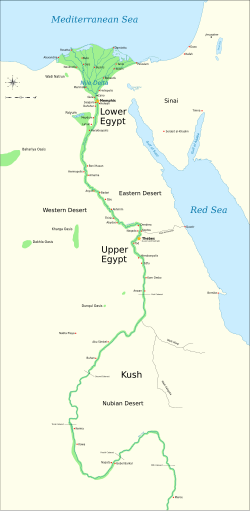

On 21 July 1828, the expedition boarded the ship Eglé at Toulon and set sail for Egypt and on 18 August they arrived in Alexandria. Here, Champollion met with Drovetti, who continued to warn about the political situation but assured Champollion that the Pasha would give his permission for the expedition to proceed. Champollion, Rosselini and Lenormant met with the Pasha on 24 August, and he immediately gave his permission. However, after more than a week of waiting for the permissions, Champollion suspected that Drovetti was working against him and took a complaint to the French consulate. The complaint worked and soon the pasha provided the expedition with a large riverboat. The expedition bought a small boat for five persons. Champollion named them the Isis and the Athyr after Egyptian goddesses. On 19 September, they arrived in Cairo, where they stayed until 1 October when they left for the desert sites of Memphis, Saqqara and Giza.[104]

While examining texts in the tombs at Saqqara in October, Champollion realized that the hieroglyphic word for "hour" included the hieroglyph representing a star, which served no phonetic function in the word. He wrote in his journal that the star-glyph was "the determinative of all divisions of time". Champollion probably coined this term, replacing his phrase "signs of the type", while in Egypt, as it had not appeared in the 1828 edition of the Précis.[105] Champollion also saw the sphinx and lamented that the inscription on its chest was covered by more sand than they would be able to remove in a week. Arriving in Dendera on 16 November, Champollion was excited to see the Zodiac that he had deciphered in Paris. Here, he realized that the glyph that he had deciphered as autocrator and which convinced him that the inscription was of recent date was in fact not found on the monument itself – it had seemingly been invented by Jomard's copyist. Champollion nonetheless realized that the late date was still correct, based on other evidence. After a day at Dendera, the expedition continued on to Thebes.[106]

Champollion was particularly captured by the array of important monuments and inscriptions at Thebes and decided to spend as much time there as possible on the way back north. South of Thebes, the Isis sprang a leak and nearly sank. Having lost many provisions and spent several days repairing the boat they continued south to Aswan where the boats had to be left, since they could not make it across the first Cataract. They travelled by small boats and camelback to Elephantine and Philae. At Philae, Champollion spent several days recovering from an attack of gout brought on by the hard trip, and he also received letters from his wife and brother, both sent many months earlier. Champollion attributed their delay to Drovetti's ill will. They arrived at Abu Simbel on 26 November, the site had been visited by Bankes and Belzoni in 1815 and 1817 respectively, but the sand that they had cleared from the entrance had now returned. On 1 January 1829, they reached Wadi Halfa and returned north. That day, Champollion composed a letter to M. Dacier stating: "I am proud now, having followed the course of the Nile from its mouth to the second cataract, to have the right to announce to you that there is nothing to modify in our 'Letter on the Alphabet of the Hieroglyphs.' Our Alphabet is good."[107]

Even though Champollion was appalled by the rampant looting of ancient artefacts and destruction of monuments, the expedition also contributed to the destruction. Most notably, while studying the Valley of the Kings, he damaged KV17, the tomb of Seti I, by removing a wall panel of 2.26 x 1.05 m in a corridor. English explorers attempted to dissuade the destruction of the tomb, but Champollion persisted, stating that he had the permission of the Muhammad Ali Pasha.[108] Champollion also carved his name into a pillar at Karnak. In a letter to the Pasha, he recommended that tourism, excavation and trafficking of artefacts be strictly controlled. Champollion's suggestions may have led to Muhammad Ali's 1835 ordinance prohibiting all exports of antiquities and ordering the construction of a museum in which to house the ancient artefacts.[109]

On the way back, they stayed again at Thebes from March to September, making many new drawings and paintings of the monuments there. Here, at the Valley of the Kings the expedition moved into the tomb of Ramesses IV (of the 20th Dynasty). They also located the tomb of Ramesses the Great, but it was badly looted. It was here that Champollion first received news of Young's campaign to vindicate himself as the decipherer of the hieroglyphs and to discredit Champollion's decipherments. He received this news only a few days after Young's death in London.[110]

In late September 1829, the expedition arrived back in Cairo, where they bought 10,000 francs worth of antiquities, a budget extended to them by minister Rochefoucauld. Arriving in Alexandria, they were notified that the French boat that would take them back was delayed, and they had to stay two months until 6 December. On their return to Alexandria, the Khedive Muhammad Ali Pasha, offered the two obelisks standing at the entrance of Luxor Temple to France in 1829, but only one was transported to Paris, where it now stands on the Place de la Concorde.[111] Champollion and the Pasha spoke often and on the Pasha's request, Champollion wrote an outline of the history of Egypt. Here, Champollion had no choice but to challenge the short Biblical chronology arguing that Egyptian civilization had its origins at least 6000 years before Islam. The two also spoke about social reforms, Champollion championing the education of the lower classes – a point on which the two did not agree.[112]

Returning to Marseille on the Côte d'Azur, the members of the expedition had to spend a month in quarantine on the ship before being able to continue on towards Paris.[113] The expedition led to a posthumously published extensive Monuments de l'Égypte et de la Nubie (1845).

Death

[edit]

After his return from the second expedition to Egypt, Champollion was appointed to the chair of Egyptian history and archaeology at the Collège de France, a chair that had been specially created for him by a decree of Louis Philippe I dated to 12 March 1831.[1] Champollion gave only three lectures before his illness forced him to give up teaching.[114] Exhausted by his labours during and after his scientific expedition to Egypt, Champollion died of an apoplectic attack (stroke) in Paris on 4 March 1832 at the age of 41.[1] His body was buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery.[115] On his tomb is a simple obelisk erected by his wife, and a stone slab stating: Ici repose Jean-François Champollion, né à Figeac dept. du Lot le 23 décembre 1790, décédé à Paris le 4 mars 1832 (Here rests Jean-François Champollion, born at Figeac, Department of the Lot, on 23 December 1790, died at Paris on 4 March 1832).[116]

Certain portions of Champollion's works were edited by Jacques and published posthumously. His Grammar and Dictionary of Ancient Egyptian had been left almost finished and was published posthumously in 1838. Before his death, he had told his brother: "Hold it carefully, I hope that it will be my calling card for posterity."[117] It contained his entire theory and method, including classifications of signs and their decipherments, and also a grammar including how to decline nouns and conjugate verbs. But it was marred by the still tentative nature of many readings, and Champollion's conviction that the hieroglyphs could be read directly in Coptic, whereas in fact, they represented a much older stage of the language, which differs in many ways from Coptic.[118]

Jacques's son, Aimé-Louis (1812–1894), wrote a biography of the two brothers,[119] and he and his sister Zoë Champollion were both interviewed by Hermine Hartleben, whose major biography of Champollion was published in 1906.[120][118]

Champollion's decipherment remained controversial even after his death. The brothers Alexander and Wilhelm von Humboldt famously championed his decipherment, as did Silvestre de Sacy, but others, such as Gustav Seyffarth, Julius Klaproth and Edmé-François Jomard sided with Young and refused to consider Champollion to be more than a talented imitator of Young even after the posthumous publication of his grammar.[121] In England, Sir George Lewis still maintained 40 years after the decipherment, that since the Egyptian language was extinct, it was a priori impossible to decipher the hieroglyphs.[122][123] In a reply to Lewis's scathing critique, Reginald Poole, an Egyptologist, defended Champollion's method, describing it as "the method of interpreting Hieroglyphics originated by Dr. Young and developed by Champollion".[124] Also Sir Peter Le Page Renouf defended Champollion's method, although he was less deferential to Young.[125]

Building on Champollion's grammar, his student Karl Richard Lepsius continued to develop the decipherment, realizing in contrast to Champollion that vowels were not written. Lepsius became the most important champion of Champollion's work. In 1866, the Decree of Canopus, discovered by Lepsius, was successfully deciphered using Champollion's method, cementing his reputation as the true decipherer of the hieroglyphs.[121]

Legacy

[edit]

Champollion's most immediate legacy is in the field of Egyptology, of which he is now widely considered as the founder and father, with his decipherment the result of his genius combined with hard work.[126]

Figeac honours him with La place des Écritures, a monumental reproduction of the Rosetta Stone by American artist Joseph Kosuth (pictured to the right).[127] And a museum devoted to Jean-François Champollion was created in his birthplace at Figeac in Lot.[128] It was inaugurated on 19 December 1986 in the presence of President François Mitterrand and Jean Leclant, Permanent Secretary of the Academy of Inscriptions and Letters. After two years of building work and extension, the museum re-opened in 2007. Besides Champollion's life and discoveries, the museum also recounts the history of writing. The whole façade is covered in pictograms, from the original ideograms of the whole world.[129]

In Vif near Grenoble, The Champollion Museum is located at the former abode of Jean-François's brother.[130]

Champollion has also been portrayed in many films and documentaries: For example, he was portrayed by Elliot Cowan in the 2005 BBC docudrama Egypt. His life and process of the decipherment of hieroglyphics were narrated by Françoise Fabian and Jean-Hugues Anglade in the 2000 Arte documentary film Champollion: A Scribe for Egypt. In David Baldacci's thriller involving the CIA, Simple Genius, the character named "Champ Pollion" was derived from Champollion.

In Cairo, a street carries his name, leading to the Tahrir Square where the Egyptian Museum is located.[131]

Also named after him is the Champollion crater, a lunar crater on the far side of the Moon.[132]

Works

[edit]- L'Égypte sous les Pharaons, ou recherches sur la géographie, la religion, la langue, les écritures et l'histoire de l'Égypte avant l'invasion de Cambyse. Tome premier: Description géographique. Introduction. Paris: De Bure. 1814. OCLC 716645794.

- L'Égypte sous les Pharaons, ou recherches sur la géographie, la religion, la langue, les écritures et l'histoire de l'Égypte avant l'invasion de Cambyse. Description géographique. Tome Second. Paris: De Bure. 1814. OCLC 311538010.

- De l'écriture hiératique des anciens Égyptiens. Grenoble: Imprimerie Typographique et Lithographique de Baratier Frères. 1821. OCLC 557937746.

- Lettre à M. Dacier relative à l'alphabet des hiéroglyphes phonétiques employés par les égyptiens pour écrire sur leurs monuments les titres, les noms et les surnoms des souverains grecs et romains. Paris: Firmin Didot Père et Fils. 1822. See also the wikipedia article Lettre à M. Dacier.

- Panthéon égyptien, collection des personnages mythologiques de l'ancienne Égypte, d'après les monuments (explanatory text to illustrations by Léon-Jean-Joseph Dubois). Paris: Firmin Didot. 1823. OCLC 743026987.

- Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens, ou recherches sur les éléments premiers de cette écriture sacrée, sur leurs diverses combinaisons, et sur les rapports de ce systéme avec les autres méthodes graphiques égytpiennes. Paris, Strasbourg, Londres: Treuttel et Würtz. 1824. OCLC 490765498.;

- Lettres à M. le Duc de Blacas d'Aulps relatives au Musée Royal Egyptien de Turin. Paris: Firmin Didot Père et Fils. 1824. OCLC 312365529.;

- Notice descriptive des monuments Égyptiens du musée Charles X. Paris: Imprimerie de Crapelet. 1827. OCLC 461098669.;

- Lettres écrites d'Égypte et de Nubie. Vol. 10764. Project Gutenberg. 1828–1829. OCLC 979571496.;

Posthumous works

[edit]- Monuments de l'Egypte et de la Nubie: d'après les dessins exécutés sur les lieux sous la direction de Champollion le-Jeune, et les descriptions autographes qu'il en a rédigées. Volume 1 & 2. Paris: Typographie de Firmin Didot Frères. 1835–1845. OCLC 603401775.

- Grammaire égyptienne, ou Principes généraux de l'ecriture sacrée égyptienne appliquée a la représentation de la langue parlée. Paris: Typographie de Firmin Didot Frères. 1836. OCLC 25326631. See also the wikipedia article Grammaire égyptienne

- Dictionnaire égyptien en écriture hiéroglyphique. Paris: Firmin Didot Frères. 1841. OCLC 943840005.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Champollion read the name Thutmose as consisting of the logogram Thoth represented by the Ibis and two phonetic signs M and S. In reality, however, the second sign was MS, not simple M, giving the actual reading THOTH-MS-S. Champollion never realized that some phonetic signs included two consonants.Gardiner (1952)

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Bianchi 2001, p. 261.

- ^ Lacouture 1988, p. 40.

- ^ Robinson 2012, p. 34.

- ^ Robinson 2012, p. ch. 2.

- ^ a b Lacouture 1988, p. 72.

- ^ Meyerson 2004, p. 31.

- ^ a b Lacouture 1988, p. 74.

- ^ Butin 1913.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 50.

- ^ a b Adkins & Adkins 2000, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Brière, L. de La. Champollion inconnu, lettres inédites. Paris, 1897. p.69

- ^ Hartleben, H. Champollion, sein Leben und sein Werk, Vol. 1, p. 81. Berlin, 1906.

- ^ Louca, A. "Champollion entre Bartholdi et Chiftichi." Mélanges Jacques Berque. Paris, 1989.

- ^ https://www.etbtoursegypt.com/Wiki/religion-in-egypt/how-did-the-coptic-language-help-champollion-in-uncovering-the-secrets-of-hieroglyphic-writing

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 51.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 66.

- ^ https://artjourneyparis.com/blog/champollion-decipherment-ancient-egyptian-hieroglyphs.html

- ^ Lacouture 1988, p. 91.

- ^ Lacouture 1988, p. 94.

- ^ Ceram, C. W. (1967). Gods, Graves, and Scholars (2nd ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 91.

- ^ Hartleben 1906, p. 65.

- ^ Weissbach 1999.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, pp. 74–76.

- ^ Åkerblad 1802.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 85.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, pp. 92–94.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, pp. 79, 205, 236.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, pp. 81, 89–90, 99–100.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 126.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, pp. 120–135.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 144.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, pp. 156–160.

- ^ Robinson 2012, p. 106.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, pp. 106–107, 147–148.

- ^ Musée Champollion de Vif 2018.

- ^ Robinson 2012, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Frimmer 1969.

- ^ Allen 1960.

- ^ Iversen 1961, p. 97.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, pp. 60–62.

- ^ a b c d e Bianchi 2001, p. 260.

- ^ a b c d e Weissbach 2000.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 87.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, pp. 97–98.

- ^ a b Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 125.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 129.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 128.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, pp. 137–140.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 142.

- ^ Robinson 2012, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, pp. 140–145.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 277.

- ^ Parkinson et al. 1999, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 172.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 122.

- ^ Champollion 1828, p. 33.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 159.

- ^ a b Robinson 2012, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Posener 1972, p. 566.

- ^ a b c Hammond 2014.

- ^ Robinson 2012, p. 130.

- ^ Robinson 2011.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 171.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Robinson 2012, pp. 133–137.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, pp. 170–175.

- ^ Robinson 2012, p. 139.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 179.

- ^ a b Robinson 2012, p. 142.

- ^ a b Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 181.

- ^ Aufrère 2008.

- ^ Robinson 2012, pp. 127–129.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, pp. 175, 187, 192.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, pp. 187–189.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 188.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 199.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, pp. 202–203.

- ^ Champollion 1828.

- ^ Champollion 1828, p. 15.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, pp. 240–41.

- ^ Pope 1999, p. 84.

- ^ Parkinson et al. 1999, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 224.

- ^ a b c Sayce, Archibald Henry (2019). The Archaeology of the Cuneiform Inscriptions. Cambridge University Press. pp. 10–14 [13, note]. ISBN 978-1-108-08239-6.

- ^ Kent, R. G.: "Old Persian: Grammar Texts Lexicon", p. 10. American Oriental Society, 1950.

- ^ a b c d Sayce, Archibald Henry (2019). The Archaeology of the Cuneiform Inscriptions. Cambridge University Press. pp. 10–14. ISBN 978-1-108-08239-6.

- ^ Recueil des publications de la Société Havraise d'Études Diverses (in French). Société Havraise d'Etudes Diverses. 1869. p. 423.

- ^ Champollion 1828, p. 232.

- ^ a b Saint-Martin, Antoine-Jean (January 1823). "Extrait d'un mémoire relatif aux antiques inscriptions de Persépolis lu à l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres". Journal asiatique (in French). Société asiatique (France): 86.

- ^ a b c Bulletin des sciences historiques, antiquités, philologie (in French). Treuttel et Würtz. 1825. p. 135.

- ^ Recueil des publications de la Société Havraise d'Études Diverses (in French). Société Havraise d'Etudes. 1869. p. 423.

- ^ Laet, Sigfried J. de; Dani, Ahmad Hasan (1994). History of Humanity: From the third millennium to the seventh century B.C. UNESCO. p. 229. ISBN 978-9231028113.

- ^ Champollion, Jean-François (1790–1832) Auteur du texte (1824). Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens, ou Recherches sur les éléments premiers de cette écriture sacrée, sur leurs diverses combinaisons, et sur les rapports de ce système avec les autres méthodes graphiques égyptiennes. Planches / . Par Champollion le jeune...

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Revue archéologique (in French). Leleux. 1844. p. 444.

- ^ a b Champollion 1828, pp. 225–233.

- ^ Champollion 1828, pp. 231–233.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tanré-Szewczyk 2017.

- ^ "Jean-François Champollion (1790–1832)". Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ Kanawaty 1990, p. 143.

- ^ Robinson 2012, p. 176.

- ^ Robinson 2012, p. 178.

- ^ Robinson 2012, pp. 179–181.

- ^ Robinson 2012, pp. 193–199.

- ^ Robinson 2012, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Robinson 2012, pp. 203–204.

- ^ Robinson 2012, p. 213.

- ^ Ridley 1991.

- ^ Fagan 2004, p. 170.

- ^ Robinson 2012, pp. 216–217.

- ^ Clayton 2001.

- ^ Robinson 2012, p. 224.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 279.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 286.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, pp. 287–288.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 307.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 292.

- ^ a b Griffith 1951.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 7.

- ^ Hartleben 1906.

- ^ a b Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 294.

- ^ Pope 1999.

- ^ Lewis 1862, p. 382.

- ^ Poole 1864, pp. 471–482.

- ^ Thomasson 2013.

- ^ Posener 1972, p. 573.

- ^ Parkinson et al. 1999, p. 43.

- ^ Journal La Semaine du Lot – Article : Figeac, musée Champollion, "Et c'est parti ... Le 3 octobre 2005" – n° 478 – du 6 au 12 octobre 2005 – p. 11.

- ^ "Les Ecritures du Monde" (in French). L'internaute – Musée Champollion. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ^ "La propriété familiale, Museum Website". Archived from the original on 13 August 2013.

- ^ "Cairo correspondent on the city's best". CNN.com.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 308.

Bibliography

[edit]- Adkins, Lesley; Adkins, Roy (2000). The Keys of Egypt: The Obsession to Decipher Egyptian Hieroglyphs. New York: Harper Collins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-019439-0.

- Åkerblad, Johan David (1802). Lettre sur l'inscription Égyptienne de Rosette: adressée au citoyen Silvestre de Sacy, Professeur de langue arabe à l'École spéciale des langues orientales vivantes, etc.; Réponse du citoyen Silvestre de Sacy. Paris: L'imprimerie de la République.

- Allen, Don Cameron (1960). "The Predecessors of Champollion". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 104 (5): 527–547. JSTOR 985236.

- Aufrère, Sydney (2008). "Champollion, Jean-François" (in French). Institut National d'Histoire de l'Art. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017.

- Clayton, Peter, ed. (2001). Egyptian Diaries: How One Man Unveiled the Mysteries of the Nile. Gibson Square. ISBN 978-1-903933-02-2.

- Bianchi, Robert Steven (2001). "Champollion Jean-François". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 260–261. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Butin, Romain Francis (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company. OCLC 945776031.

- Champollion, J.-F. (1828). Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens, ou, Recherches sur les élémens premiers de cette écriture sacrée, sur leurs diverses combinaisons, et sur les rapports de ce système avec les autres méthodes graphiques égyptiennes (in French). Revue par l'auteur et augmentée de la Lettre à M. Dacier, relative à l'alphabet des hiéroglyphes phonétiques employés par les Egyptiens sur leurs monumens de l'époque grecque et de l'époque romaine (2 ed.). Paris: Imprimerie royale. OCLC 489942666.

- Fagan, B. M. (2004). The rape of the Nile: tomb robbers, tourists, and archaeologists in Egypt (Revised and updated ed.). Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-4061-6.

- Frimmer, Steven (1969). The stone that spoke: and other clues to the decipherment of lost languages. Science survey book. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. OCLC 11707.

- Gardiner, A. H. (1952). "Champollion and the Biliteral Signs". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 38: 127–128. doi:10.2307/3855503. JSTOR 3855503.

- Griffith, F. L. (1951). "The Decipherment of the Hieroglyphs". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 37: 38–46. doi:10.2307/3855155. JSTOR 3855155.

- Hammond, N. (2014). "Cracking the Egyptian Code: The Revolutionary Life of Jean-François Champollion". European Journal of Archaeology. 17 (1): 176–179. doi:10.1179/146195714x13820028180487. S2CID 161646266.

- Hartleben, Hermine (1906). Champollion: sein leben und sein Werk (in German). Vol. 1. Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung. OCLC 899972029.

- Iversen, Erik (1961). Myth of Egypt and its hieroglyphs in European tradition. Copenhagen: Gad. OCLC 1006828.

- Kanawaty, Monique (1990). "Pharaon entre au Louvre". Mémoires d'Égypte. Hommage de l'Europe à Champollion, catalogue d'exposition, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, 17 novembre 1990–17 mars 1991 (in French). Strasbourg: La Nuée Bleue. OCLC 496441116.

- Lacouture, Jean (1988). Champollion, Une vie de lumières (in French). Paris: Grasset. ISBN 978-2-246-41211-3.

- Lewis, George Cornewall (1862). An Historical Survey of the Astronomy of the Ancients. London: Parker, Son, and Bourn. p. 382. OCLC 3566805.

Sir George Lewis on Champollion.

- Meyerson, Daniel (2004). The linguist and the emperor: Napoleon and Champollion's quest to decipher the Rosetta Stone. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-45067-8.

- "Musée Champollion. Vif". Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- Parkinson, Richard; Diffie, Whitfield; Fischer, M.; Simpson, R. S. (1999). Cracking Codes: the Rosetta stone and decipherment. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22248-9.

- Poole, Reginald Stuart (1864). "XXVI. On the method of interpreting Egyptian Hieroglyphics by Young and Champollion, with a vindication of its correctness from the strictures of Sir George Cornewall Lewis". Archaeologia. 39 (2): 471–482. doi:10.1017/s026134090000446x.

- Pope, Maurice (1999). The Story of Decipherment: From Egyptian Hieroglyphs to Maya Script (Revised ed.). New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28105-5.

- Posener, George (1972). "Champollion et le déchiffrement de l'écriture hiératique". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. 116 (3): 566–573.

- Ridley, R. T. (1991). "Champollion in the Tomb of Seti I: an Unpublished Letter". Chronique d'Égypte. 66 (131): 23–30. doi:10.1484/j.cde.2.308853.

- Robinson, Andrew (2012). Cracking the Egyptian Code: The Revolutionary Life of Jean-Francois Champollion. Oxford University Press.

- Robinson, A. (2011). "Styles of Decipherment: Thomas Young, Jean-François Champollion and the Decipherment of the Egyptian Hieroglyphs" (PDF). Scripta. 3: 123–132. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- Tanré-Szewczyk, Juliette (2017). "Des antiquités égyptiennes au musée. Modèles, appropriations et constitution du champ de l'égyptologie dans la première moitié du XIXe siècle, à travers l'exemple croisé du Louvre et du British Museum". Les Cahiers de l'École du Louvre (in French). 11 (11). doi:10.4000/cel.681.

- Thomasson, Fredrik (2013). The Life of J. D. Åkerblad: Egyptian Decipherment and Orientalism in Revolutionary Times. Brill's studies in intellectual history. Vol. 123. Leiden; Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-1-283-97997-9.

- Weissbach, M. M. (2000). "Jean François Champollion and the True Story of Egypt" (PDF). 21st Century Science and Technology. 12 (4): 26–39.

- Weissbach, Muriel Mirak (1999). "How Champollion deciphered the Rosetta stone". Fidelio. VIII (3).

- Wilkinson, Toby (2020). A World Beneath the Sands: Adventurers and Archaeologists in the Golden Age of Egyptology (Hardbook). London: Picador. ISBN 978-1-5098-5870-5.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch