Chiltern Court

| Chiltern Court | |

|---|---|

"a stately classical pile" | |

| Type | Block of flats |

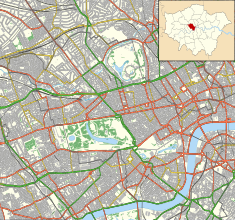

| Location | Baker Street, London |

| Coordinates | 51°31′22″N 0°09′23″W / 51.5227°N 0.1564°W |

| Built | 1927-29 |

| Architect | Charles Walter Clark |

| Architectural style(s) | Neo-classical |

Chiltern Court, Baker Street, London, is a large block of flats at the street's northern end, facing Regent's Park and Marylebone Road. It was built between 1927 and 1929 above Baker Street tube station by the Metropolitan Railway.

It was begun in 1912 and was originally intended as a hotel and as its company headquarters, but the Metropolitan's plans were interrupted by the First World War. When construction recommenced in the late 1920s, the building was redesigned as a block of flats and the Chiltern Court Restaurant. The architect was Charles Walter Clark.

During the 1930s the block was home to a number of notable figures, including the writers H. G. Wells, who held a weekly literary salon at his apartment, and Arnold Bennett, who died at the Court in 1931. The composer Eric Coates lived in the block between 1930 and 1936, and the cartoonist David Low was also a resident. During World War II, the Special Operations Executive was based at 64 Baker Street, and its Norwegian Section was located in three flats at Chiltern Court, from where it directed the operations against the heavy water plant at Telemark.

Chiltern Court is not listed, being specifically excluded from the listing designation for Baker Street tube station. It is recorded in Pevsner, where it is described as "a stately classical pile, the grandest [of the] mansion flats" in the vicinity.[1] The Chiltern Court Restaurant, now a bar, was referenced by John Betjeman in his television programme from 1973, Metro-land.

History

[edit]Baker Street station opened in 1863 as part of the development of the Metropolitan Railway which linked Paddington Station with Farringdon station,[2] both in central London. It was the world's first truly underground railway.[3] Over the next four decades the Metropolitan Railway extended its network, principally into the suburbs to the north and west of London, an area that became known as Metro-land,[4] and many of the train services to/from these locations started from/terminated at Baker Street.

In 1912 the company determined to construct a new headquarters building, and a hotel, above its Baker Street terminus. Its plans were interrupted by the First World War, and construction did not recommence until 1927.[2] At this point, plans for the hotel were abandoned, and the company's in-house architect Charles Walter Clark drew up designs for an apartment block with attached restaurant.[5] Building was complete by 1929.[6][7] The finished block contained 180 apartments, the Chiltern Court Restaurant, a hairdressers and staff accommodation.[8]

The apartments, which were expensive, attracted a range of notable residents. The writer H. G. Wells lived at the Court from 1930 to 1936, regularly hosting a weekly literary salon attended by friends, fellow authors and members of London society.[9] The cartoonist David Low, a friend and attender at Wells' gatherings, also lived in the block.[10][9] The author Arnold Bennett bought a flat in the building in 1930, and died there in March 1931 after contracting typhoid fever.[11][12] As Bennett was dying, the local council permitted the laying of straw along the Marylebone Road outside Chiltern Court to lessen the noise of traffic, reportedly the last time this courtesy was permitted in London.[a][13] Another resident in the 1930s was the composer Eric Coates who lived in Flat 176 between 1930 and 1939.[b][15]

During World War II the Special Operations Executive (SOE) was based at 64 Baker Street, hence its nickname, the Baker Street Irregulars.[16] The SOE had a Norwegian Section which was located in three flats at Chiltern Court. From this base, SOE operatives planned and instigated the attacks against the heavy water plant at Telemark where, following the German occupation of Norway in 1940, the Nazis sought to exploit the heavy water as a component of their nuclear weapons programme.[c][18]

In 1973 John Betjeman, the Poet Laureate, began his TV documentary Metro-Land in the Chiltern Court Restaurant. The programme saw Betjeman travel from Chiltern Court to Verney Junction railway station, the (by then long-disused) farthest outpost of the Metropolitan line in Buckinghamshire.[d][19] Chiltern Court remains a privately operated block of residential flats.[12]

The former Chiltern Court Restaurant, entered from Marylebone Road, is now operated as a pub, the Metropolitan Bar, by Wetherspoons.[20] It has coats of arms on the walls of places linked to the Metropolitan Railway.[21]

Architecture and description

[edit]Chiltern Court comprises seven storeys, a two-storey plinth with retail units on the ground floor, then three main storeys with residential accommodation and two attic storeys.[1] The whole is faced in Portland stone, and is designed in a Neoclassical style.[22] Bridget Cherry, in her 2002 revision to the London 3: North West volume of the Pevsner Buildings of England series, describes it as "a stately classical pile, the grandest of [the] mansion flats" in the area.[1]

The building holds four Blue and other commemorative plaques, commemorating its occupants and history. Chiltern Court is not listed by Historic England, the listing for the Grade II* Baker Street Station specifically excluding the Court.[23]

Gallery

[edit]- Plaque commemorating H. G. Wells

- Plaque commemorating Arnold Bennett

- Plaque commemorating Eric Coates

- Plaque commemorating the Telemark Raids

- The surgeon Sir Vincent Zachary Cope who lived at the court from 1944

- The cartoonist David Low who lived at the court in the 1930s

- Chiltern Court from the Marylebone Road

- Metropolitan Bar (formerly Chiltern Court Restaurant) in 2020

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The council's consideration to the dying Bennett was marred by the overturning of a milk float in the street just hours after Bennett's death, which propelled the milk churns into the road with a "thunderous din".[13]

- ^ Eric Coates' best known composition is perhaps By the Sleepy Lagoon, which is still regularly played as the opening theme to BBC Radio 4's Desert Island Discs.[14]

- ^ While ultimately successful in its efforts to impede the German production and exportation of heavy water, the SOE's incursions led to considerable loss of life. Operation Freshman, in November 1942, saw particularly heavy casualties.[17]

- ^ Betjeman begins his commentary with the lines "Is this Buckingham Palace? Are we at The Ritz? No, this is the Chiltern Court Restaurant, built above Baker Street Station, the gateway between Metro-land and London."

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Cherry & Pevsner 2002, p. 658.

- ^ a b Cherry & Pevsner 2002, pp. 614–615.

- ^ Green 1987, pp. 3–5.

- ^ Jackson 1986, p. 240.

- ^ "Chiltern Court, London". RIBA. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ "BAM History Timeline 1900s-1940s". www.bam.co.uk. BAM Group. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "Drawing: Baker Street Station - showing Proposed Flats (Chiltern Court) and Restaurant". London Transport Museum. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "Chiltern Court and Baker Street Underground Station". Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ a b Rodionova, Zlata (10 November 2015). "See the flat where H. G. Wells hosted a book club". The Independent.

- ^ Nierynck, Robin (11 November 2015). "H. G. Wells Marylebone 'book club' flat". Ham&High.

- ^ Avis-Riordan, Katie (20 February 2018). "Baker Street apartment where H. G. Wells and Arnold Bennet lived is now for sale". House Beautiful.

- ^ a b Ebert, Jennifer (21 April 2018). "The Baker Street apartment where H. G. Wells and Arnold Bennett lived". Ideal Home.

- ^ a b Pound 1953, p. 367.

- ^ Parr, Freya (31 January 2022). "What is the Desert Island Discs theme tune?". BBC Music.

- ^ "Eric Coates, Composer: Blue Plaques". English Heritage. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "App to mark London's secret war". Heritage Fund. 26 January 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "Operation Freshman - The Rjukan Heavy Water Raid 1942". Assault Glider Trust. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "Heroism in Baker Street" (PDF). St Marylebone Society. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Turner, E. S. (2 December 2004). "The Thought of Ruislip". London Review of Books. 26 (23).

- ^ "The Metropolitan Bar, Baker Street". J D Wetherspoon. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "Metropolitan Bar". CAMRA.

- ^ "Dorset Square Conservation Area". Westminster City Council. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "Baker Street Station (Grade II*) (1239815)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

Sources

[edit]- Cherry, Bridget; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2002). London 3: North West. The Buildings of England. New Haven, US and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09652-1. OCLC 1080901081.

- Green, Oliver (1987). The London Underground: An illustrated history. London: Ian Allan Publishing. OCLC 926303204.

- Jackson, Alan (1986). London's Metropolitan Railway. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-715-38839-6. OCLC 909977852.

- Pound, Reginald (1953). Arnold Bennett: A Biography. New York: Harcourt, Brace. OCLC 950552766.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch