Agriculture in China

The People's Republic of China (PRC) primarily produces rice, wheat, potatoes, tomatoes, sorghum, peanuts, tea, millet, barley, cotton, oilseed, corn and soybeans.

History

[edit]The development of farming over the course of China's history has played a key role in supporting the growth of one of the largest populations in the world.

Archaeology

[edit]Analysis of stone tools by Professor Liu Li and others has shown that hunter-gatherers 23,000–19,500 years ago ground wild plants with the same tools that would later be used for millet and rice.[1]

Domesticated millet varieties Panicum miliaceum and Setaria italica may have originated in Northern China.[2] Remains of domesticated millet have been found in northern China at Xinglonggou, Yuezhang, Dadiwan, Cishan, and several Peiligang sites. These sites cover a period over 7250-6050 BCE.[3] The amount of domesticated millet eaten at these sites was proportionally quite low compared to other plants. At Xinglonggou, millet made up only 15% of all plant remains around 7200-6400 BCE; a ratio that changed to 99% by 2050-1550 BCE.[4] Experiments have shown that millet requires very little human intervention to grow, which means that obvious changes in the archaeological record that could demonstrate millet was being cultivated do not exist.[3]

Excavations at Kuahuqiao, the earliest known Neolithic site in eastern China, have documented rice cultivation 7,700 years ago.[5] Approximately half of the plant remains belonged to domesticated japonica species, whilst the other half were wild types of rice. It is possible that the people at Kuahuqiao also cultivated the wild type.[3] Finds at sites of the Hemudu Culture (c. 5500-3300 BCE) in Yuyao and Banpo near Xi'an include millet and spade-like tools made of stone and bone. Evidence of settled rice agriculture has been found at the Hemudu site of Tianluoshan (5000-4500 BCE), with rice becoming the backbone of the agricultural economy by the Majiabang culture in southern China.[6] According to the Records of the Grand Historian some female prisoners in historic times were given the punishment to be "grain pounders" (Chinese: 刑舂) as an alternative to more severe corporal punishment like tattooing or cutting off a foot. Some scholars believe the four or five year limits on these hard labor sentences began with Emperor Wen's legal reforms.[7]

There is also a long tradition involving agriculture in Chinese mythology. In his book Permanent Agriculture: Farmers of Forty Centuries (1911), Professor Franklin Hiram King described and extolled the values of the traditional farming practices of China.[8]

Farming method improvements

[edit]

Farming in China has always been very labor-intensive. However, throughout its history, various methods have been developed or imported that enabled greater farming production and efficiency. They also utilized the seed drill to help improve on row farming.

During the Spring and Autumn period (722–481 BC), two revolutionary improvements in farming technology took place. One was the use of cast iron tools and beasts of burden to pull plows, and the other was the large-scale harnessing of rivers and development of water conservation projects. The engineer Sunshu Ao of the 6th century BC and Ximen Bao of the 5th century BC are two of the oldest hydraulic engineers from China, and their works were focused on improving irrigation systems.[9] These developments were widely spread during the ensuing Warring States period (403–221 BC), culminating in the enormous Du Jiang Yan Irrigation System engineered by Li Bing by 256 BC for the State of Qin in ancient Sichuan.

For agricultural purposes the Chinese had invented the hydraulic-powered trip hammer by the 1st century BC, during the ancient Han dynasty (202 BC-220 AD).[10] Although it found other purposes, its main function was to pound, decorticate, and polish grain that otherwise would have been done manually. The Chinese also innovated the square-pallet chain pump by the 1st century AD, powered by a waterwheel or oxen pulling on a system of mechanical wheels.[11] Although the chain pump found use in public works of providing water for urban and palatial pipe systems,[12] it was used largely to lift water from a lower to higher elevation in filling irrigation canals and channels for farmland.[13]

Chinese ploughs from Han times on fulfil all these conditions of efficiency nicely, which is presumably why the standard Han plough team consisted of two animals only, and later teams usually of a single animal, rather than the four, six or eight draught animals common in Europe before the introduction of the curved mould-board and other new principles of design in the + 18th century. Though the mould-board plough first appeared in Europe in early medieval, if not in late Roman, times, pre-eighteenth century mould-boards were usually wooden and straight (Fig. 59). The enormous labour involved in pulling such a clumsy construction necessitated large plough-teams, and this meant that large areas of land had to be reserved as pasture. In China, where much less animal power was required, it was not necessary to maintain the mixed arable-pasture economy typical of Europe: fallows could be reduced and the arable area expanded, and a considerably larger population could be supported than on the same amount of land in Europe.[14]

— Francesca Bray

During the Eastern Jin (317–420) and the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420–589), the Silk Road and other international trade routes further spread farming technology throughout China. Political stability and a growing labor force led to economic growth, and people opened up large areas of wasteland and built irrigation works for expanded agricultural use. As land-use became more intensive and efficient, rice was grown twice a year and cattle began to be used for plowing and fertilization.

By the Tang dynasty (618–907), China had become a unified feudal agricultural society again. Improvements in farming machinery during this era included the moldboard plow and watermill. Later during the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), cotton planting and weaving technology were extensively adopted and improved.

While around 750, 75% of China's population lived north of the river Yangtze, by 1250, 75% of the population lived south of the river. Such large-scale internal migration was possible due to the introduction of quick-ripening strains of rice from Vietnam suitable for multi-cropping.[15] This is also possibly the result of Northern China falling to invaders. With the hardships that come from conflict, many Chinese may have moved South to not starve.

The Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties had seen the rise of collective help organizations between farmers.[16]

In 1909 US Professor of Agriculture Franklin Hiram King made an extensive tour of China (as well as Japan and briefly Korea) and he described contemporary agricultural practices. He favourably described the farming of China as 'permanent agriculture' and his book 'Farmers of Forty Centuries', published posthumously in 1911, has become an agricultural classic and has been a favoured reference source for organic farming advocates. The book has inspired many community-supported agriculture farmers in China to conduct ecological farming.[17]

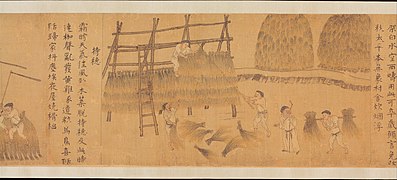

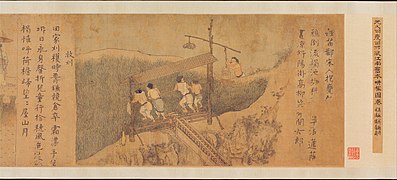

- Scroll depicting rice production, Yuan dynasty

People's Republic of China

[edit]

Following the Chinese Communist Party's victory in the Chinese Civil War, control of the farmlands was taken away from landlords and redistributed to the 300 million peasant farmers,[18] including purges of landlords during the Land Reform Movement. In 1952, gradually consolidating its power following the civil war, the government began organizing the peasants into teams. Three years later, these teams were combined into producer cooperatives, enacting the socialist goal of collective land ownership. In the following year, 1956, the government formally took control of the land, further structuring the farmland into large government-operated collective farms.

Collectivization was a factor in the most important change in Chinese agriculture in the dramatic increase in irrigated land during the early and mid-1950s.[19]: 111 Collectivization also helped facilitate the labor-intensive practice of double-cropping in southern China, which greatly increased agricultural yields.[19]: 116

In the 1958 "Great Leap Forward" campaign initiated by Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party Mao Zedong, land use was placed under closer government control in an effort to improve agricultural output. In particular, the Four Pests campaign and mass eradication of sparrows had a direct negative impact on agriculture. Collectives were organized into communes, private food production was banned, and collective eating was required. Greater emphasis was also put on industrialization instead of agriculture. The farming inefficiencies created by this campaign led to the Great Chinese Famine, resulting in the deaths of somewhere between the government estimate of 14 million to scholarly estimates of 20 to 43 million.[20] Although private plots of land were re-instated in 1962 due to this failure, communes remained the dominant rural unit of economic organization during the Cultural Revolution, with Mao championing the "Learn from Dazhai in agriculture" campaign. Tachai's semi-literate party secretary Chen Yonggui was among those outmaneuvered by Deng Xiaoping after the death of Mao: from 1982 to 1985, the Dazhai-style communes were gradually replaced by townships.

Beginning in 1978, as part of the Four Modernizations campaign, the Family Production Responsibility System was created, dismantling communes and giving agricultural production responsibility back to individual households. Households are now given crop quotas that they were required to provide to their collective unit in return for tools, draft animals, seeds, and other essentials. Households, which now lease land from their collectives, are free to use their farmland however they see fit as long as they meet these quotas. This freedom has given more power to individual families to meet their individual needs. In addition to these structural changes, the Chinese government also engages in irrigation projects (such as the Three Gorges Dam), runs large state farms, and encourages mechanization and fertilizer use.[21]

By 1984, when about 99% of farm production teams had adopted the Family Production Responsibility System, the government began further economic reforms, aimed primarily at liberalizing agricultural pricing and marketing. In 1984, the government replaced mandatory procurement with voluntary contracts between farmers and the government. Later, in 1993, the government abolished the 40-year-old grain rationing system, leading to more than 90 percent of all annual agricultural produce to be sold at market-determined prices.

Since 1994, the government has instituted a number of policy changes aimed at limiting grain importation and increasing economic stability. Among these policy changes was the artificial increase of grain prices above market levels. This has led to increased grain production, while placing the heavy burden of maintaining these prices on the government. In 1995, the "Governor's Grain Bag Responsibility System" was instituted, holding provincial governors responsible for balancing grain supply and demand and stabilizing grain prices in their provinces. Later, in 1997, the "Four Separations and One Perfection" program was implemented to relieve some of the monetary burdens placed on the government by its grain policy.[22]

As China continues to industrialize, vast swaths of agricultural land are being converted into industrial land. Farmers displaced by such urban expansion often become migrant labor for factories, but other farmers feel disenfranchised and cheated by the encroachment of industry and the growing disparity between urban and rural wealth and income.[23]

The most recent innovation in Chinese agriculture is a push into organic agriculture.[24] This rapid embrace of organic farming simultaneously serves multiple purposes, including food safety, health benefits, export opportunities, and, by providing price premiums for the produce of rural communities, the adoption of organics can help stem the migration of rural workers to the cities.[24] In the mid-1990s China became a net importer of grain, since its unsustainable practises of groundwater mining has effectively removed considerable land from productive agricultural use.[citation needed]

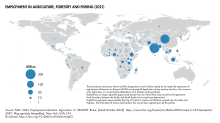

As of 2023, approximately 40% of China's workforce is engaged in farming, primarily at small scale.[25]: 174 Agricultural production accounts for less than 9% of China's GDP.[25]: 174

Major agricultural products

[edit]Crop distribution

[edit]

Although China's agricultural output is the largest in the world, only 10% of its total land area can be cultivated. China's arable land, which represents 10% of the total arable land in the world, supports over 20% of the world's population.[26] Of this approximately 1.4 million square kilometers of arable land, only about 1.2% (116,580 square kilometers) permanently supports crops and 525,800 square kilometers are irrigated.[citation needed] The land is divided into approximately 200 million households, with an average land allocation of just 0.65 hectares (1.6 acres).

China's limited space for farming has been a problem throughout its history, leading to chronic food shortage and famine. While the production efficiency of farmland has grown over time, efforts to expand to the west and the north have met with limited success, as such land is generally colder and drier than traditional farmlands to the east. Since the 1950s, farm space has also been pressured by the increasing land needs of industry and cities.

Peri-urban agriculture

[edit]

Such increases in the sizes of cities, such as the administrative district of Beijing's increase from 4,822 km2 (1,862 sq mi) in 1956 to 16,808 km2 (6,490 sq mi) in 1958, has led to the increased adoption of peri-urban agriculture. Such "suburban agriculture" led to more than 70% of non-staple food in Beijing, mainly consisting of vegetables and milk, to be produced by the city itself in the 1960s and 1970s. Recently, with relative food security in China, periurban agriculture has led to improvements in the quality of the food available, as opposed to quantity. One of the more recent experiments in urban agriculture is the Modern Agricultural Science Demonstration Park in Xiaotangshan.[27]

Food crops

[edit]

About 75% of China's cultivated area is used for food crops. Rice is China's most important crop, raised on about 25% of the cultivated area. The majority of rice is grown south of the Huai River, in the Zhu Jiang delta, and in the Yunnan, Guizhou, and Sichuan provinces.

Wheat is the second most-prevalent grain crop, grown in most parts of the country but especially on the North China Plain, the Wei and Fen River valleys on the Loess plateau, and in Jiangsu, Hubei, and Sichuan provinces. Corn and millet are grown in north and northeast China, and oats are important in Inner Mongolia and Tibet.

Other crops include sweet potatoes in the south, white potatoes in the north (China is the largest producer of potatoes in the world), and various other fruits and vegetables. Tropical fruits are grown on Hainan Island, apples and pears are grown in northern Liaoning and Shandong.

Oil seeds are important in Chinese agriculture, supplying edible and industrial oils and forming a large share of agricultural exports. In North and Northeast China, Chinese soybeans are grown to be used in tofu and cooking oil. China is also a leading producer of peanuts, which are grown in Shandong and Hebei provinces. Other oilseed crops are sesame seeds, sunflower seeds, rapeseed, and the seeds of the tung tree.

Citrus is a major cash crop in southern China, with production scattered along and south of the Yangtze River valley. Mandarins are the most popular citrus in China, with roughly double the output of oranges.[28]

Other important food crops for China include green and jasmine teas (popular among the Chinese population), black tea (as an export), sugarcane, and sugar beets. Tea plantations are located on the hillsides of the middle Yangtze Valley and in the southeast provinces of Fujian and Zhejiang. Sugarcane is grown in Guangdong and Sichuan, while sugar beets are raised in Heilongjiang province and on irrigated land in Inner Mongolia. Lotus is widely cultivated throughout southern China.[29][30]

Arabica coffee is grown in the southwestern province of Yunnan.[31] Much smaller plantations also exist in Hainan and Fujian.[32]

Fiber crops

[edit]

China is the leading producer of cotton, which is grown throughout, but especially in the areas of the North China Plain, the Yangtze river delta, the middle Yangtze valley, and the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. Other fiber crops include ramie, flax, jute, and hemp. Sericulture, the practice of silkworm raising, is also practiced in central and southern China.

Livestock

[edit]China has a large livestock population, with pigs and fowls being the most common. China's pig population and pork production mainly lie along the Yangtze River. In 2011, Sichuan province had 51 million pigs (11% of China's total supply).[33] In rural western China, sheep, goats, and camels are raised by nomadic herders.[34] In Tibet, yaks are raised as a source of food, fuel, and shelter. Cattle, water buffalo, horses, mules, and donkeys are also raised in China, and dairy has recently been encouraged by the government, even though approximately 92.3% of the adult population is affected by some level of lactose intolerance.

As demand for gourmet foods grows, production of more exotic meats increases as well. Based on survey data from 684 Chinese turtle farms (less than half of the all 1,499 officially registered turtle farms in the year of the survey, 2002), they sold over 92,000 tons of turtles (around 128 million animals) per year; this is thought to correspond to the industrial total of over 300 million turtles per year.[35]

Increased incomes and increased demand for meat, especially pork, has resulted in demand for improved breeds of livestock, breeding stock imported particularly from the United States. Some of these breeds are adapted to factory farming.[36]

Fishing

[edit]China accounts for about one-third of the total fish production of the world. Aquaculture, the breeding of fish in ponds and lakes, accounts for more than half of its output. The principal aquaculture-producing regions are close to urban markets in the middle and lower Yangtze valley and the Zhu Jiang delta.

Production

[edit]In its first fifty years, the People's Republic of China greatly increased agricultural production through organizational and technological improvements. As of at least 2022, China produces almost all of its own food and non-soybean feed.[19]: 230

| Crop[37] | 1949 Output (tons) | 1978 Output (tons) | 1999 Output (tons) | |

| 1. | Grain | 113,180,000 | 304,770,000 | 508,390,000 |

| 2. | Cotton | 444,000 | 2,167,000 | 3,831,000 |

| 3. | Oil-bearing crops | 2,564,000 | 5,218,000 | 26,012,000 |

| 4. | Sugarcane | 2,642,000 | 21,116,000 | 74,700,000 |

| 5. | Sugarbeet | 191,000 | 2,702,000 | 8,640,000 |

| 6. | Flue-cured tobacco | 43,000 | 1,052,000 | 2,185,000 |

| 7. | Tea | 41,000 | 268,000 | 676,000 |

| 8. | Fruit | 1,200,000 | 6,570,000 | 62,376,000 |

| 9. | Meat | 2,200,000 | 8,563,000 | 59,609,000 |

| 10. | Aquatic products | 450,000 | 4,660,000 | 41,220,000 |

As of 2011, China was both the world's largest producer and consumer of agricultural products.[38][39] However, the researcher Lin Erda has stated a projected fall of possibly 14% to 23% by 2050 due to water shortages and other impacts by climate change; China has increased the budget for agriculture by 20% in 2009, and continues to support energy efficiency measures, renewable technology, and other efforts with investments, such as the over 30% green component of the $586bn fiscal stimulus package announced in November 2008.[40]

In 2018:[41]

- It was the 2nd largest producer of maize (257.1 million tons), second only to the USA;

- It was the largest producer of rice (212.1 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of wheat (131.4 million tons);

- It was the 3rd largest producer of sugarcane (108 million tons), second only to Brazil and India;

- It was the largest producer of potato (90.2 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of watermelon (62.8 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of tomatoes (61.5 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of cucumber / pickles (56.2 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of sweet potato (53.0 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of apple (39.2 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of eggplant (34.1 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of cabbage (33.1 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of onion (24.7 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of spinach (23.8 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of garlic (22.2 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of green bean (19.9 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of tangerine (19.0 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of carrots (17.9 million tons);

- It was the 3rd largest producer of cotton (17.7 million tons), second only to India and the USA;

- It was the largest producer of peanut (17.3 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of pear (16.0 million tons);

- It was the 4th largest producer of soy (14.1 million tons), losing to the US, Brazil and Argentina;

- It was the largest producer of grape (13.3 million tons);

- It was the 2nd largest producer of rapeseed (13.2 million tons), second only to Canada;

- It was the largest producer of pea (12.9 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of melon (12.7 million tons);

- It was the 8th largest producer of sugar beet (12 million tons), which serves to produce sugar and ethanol;

- It was the 2nd largest producer of banana (11.2 million tons), second only to India;

- It was the largest producer of cauliflower and broccoli (10.6 million tons);

- It was the 2nd largest producer of orange (9.1 million tons), second only to Brazil;

- It was the largest producer of pumpkin (8.1 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of asparagus (7.9 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of plum (6.7 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of mushroom and truffle (6.6 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of grapefruit (4.9 million tons);

- It was the 15th largest producer of cassava (4.9 million tons);

- It was the 2nd largest producer of mango (including mangosteen and guava) (4.8 million tons), second only to India;

- It was the largest producer of persimmon (3.0 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of strawberry (2.9 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of tea (2.6 million tons);

- It produced 2.5 million tons of sunflower seed;

- It was the 3rd largest producer of lemon (2.4 million tons), second only to India and Mexico;

- It was the largest producer of tobacco (2.2 million tons);

- It was the 8th largest producer of sorghum (2.1 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of kiwi (2.0 million tons);

- It was the largest producer of chestnut (1.9 million tons);

- It produced 1.9 million tons of taro;

- It produced 1.8 million tons of fava beans;

- It was the 3rd largest producer of millet (1.5 million tons), second only to India and Niger;

- It was the 8th largest producer of pineapple (1.5 million tons);

- It produced 1.4 million tons of barley;

- It was the largest producer of buckwheat (1.1 million tons);

- It was the 6th largest producer of oats (1 million tons);

- It was the 4th largest producer of rye (1 million tons), second only to Germany, Poland and Russia;

- It produced 1 million tons of tallow tree;

In addition to smaller productions of other agricultural products.[41]

Challenges

[edit]

Throughout China's history, its relative lack of arable land has been a challenge.[42] China has about 22% of the world population, but must feed it with only 9% of the world's arable land.[42] China's water resources are likewise limited, as it has only 6% of the world's water supply.[42]

Inefficiencies in the agricultural market

[edit]Despite rapid growth in output, the Chinese agricultural sector still faces several challenges. Farmers in several provinces, such as Shandong, Zhejiang, Anhui, Liaoning, and Xinjiang often have a hard time selling their agricultural products to customers due to a lack of information about current conditions.[43]

Between the producing farmer in the countryside and the end-consumer in the cities there is a chain of intermediaries.[43] Because a lack of information flows through them, farmers find it difficult to foresee the demand for different types of fruits and vegetables. In order to maximize their profits they, therefore, opt to produce those fruits and vegetables that created the highest revenues for farmers in the region in the previous year. If, however, most farmers do so, this causes the supply of fresh products to fluctuate substantially year on year. Relatively scarce products in one year are produced in excess the following year because of expected higher profit margins. The resulting excess supply, however, forces farmers to reduce their prices and sell at a loss. The scarce, revenue creating products of one year become the over-abundant, loss-making products in the following, and vice versa.[44]

Efficiency is further impaired in the transportation of agricultural products from the farms to the actual markets. According to figures from the Commerce Department, up to 25% of fruits and vegetables rot before being sold, compared to around 5% in a typical developed country. As intermediaries cannot sell these rotten fruits they pay farmers less than they would if able to sell all or most of the fruits and vegetables. This reduces farmer's revenues although the problem is caused by post-production inefficiencies, which they are not themselves aware of during price negotiations with intermediaries.[45]

These information and transportation problems highlight inefficiencies in the market mechanisms between farmers and end-consumers, impeding farmers from taking advantage of the fast development of the rest of the Chinese economy. The resulting small profit margin does not allow them to invest in the necessary agricultural inputs (machinery, seeds, fertilizers, etc.) to raise their productivity and improve their standards of living, from which the whole of the Chinese economy would benefit. This in turn increases the exodus of people from the countryside to the cities, which already face urbanization issues.[46]

In a speech in September 2020, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party Xi Jinping directed China's scientists to research seed farming. He noted that the country relies on imported seed and said that its scientists must help remedy this situation.[47]

Climate change

[edit]The negative effects on China's agriculture caused by climate change have appeared. There was an increase in agricultural production instability, severe damages caused by high temperature and drought, and lower production and quality in the prairie. In the near future, climate change may cause negative influences, causing a reduction of output in wheat, rice, and corn, and change the agricultural distribution of production.[48] China is also dealing with agricultural issues due global demands of products such as soybeans. This global demand is causing coupled effects that stretch across oceans which in turn is affecting other countries.[citation needed]

Over the past 70 years, climate change seriously reduced China's food security, mainly by inducing drought and flooding. Flooding decreased the yields of rice by 8% over the last 20 years. As China is the biggest food producer and importer in the world, what happens in the agricultural sector of China has an immediate effect on the global food system. China increased its grain self sufficiency by expanding agriculture areas to regions with less rain, giving them water with irrigation systems. Now those fields are at risk from water shortage while the irrigation systems demand huge amounts of water what cause depletion of groundwater in many regions. The government of China is trying to address the problem by different measures like reducing food waste, increasing international cooperation. But some of the measures like using more fertilizers produced from coal can exacerbate the problem.[49]International trade

[edit]

China is the world's largest importer of soybeans and other food crops,[50] and is expected to become the top importer of farm products within the next decade.[51] In a speech in September 2020, CCP leader Xi Jinping lamented the country's reliance on imported seed.[47]

While most years China's agricultural production is sufficient to feed the country, in down years, China has to import grain. Due to the shortage of available farm land and an abundance of labor, it might make more sense to import land-extensive crops (such as wheat and rice) and to save China's scarce cropland for high-value export products, such as fruits, nuts, or vegetables. In order to maintain grain independence and ensure food security, however, the Chinese government has enforced policies that encourage grain production at the expense of more-profitable crops. Despite heavy restrictions on crop production, China's agricultural exports have greatly increased in recent years.[52]

Governmental influence

[edit]One important motivator of increased international trade was China's inclusion in the World Trade Organization (WTO) on December 11, 2001, leading to reduced or eliminated tariffs on much of China's agricultural exports. Due to the resulting opening of international markets to Chinese agriculture, by 2004 the value of China's agricultural exports exceeded $17.3 billion (US). Since China's inclusion in the WTO, its agricultural trade has not been liberalized to the same extent as its manufactured goods trade. Markets within China are still relatively closed-off to foreign companies. Due to its large and growing population, it is speculated that if its agricultural markets were opened, China would become a consistent net importer of food, possibly destabilizing the world food market. The barriers enforced by the Chinese government on grains are not transparent because China's state trading in grains is conducted through its Cereal, Oil, and Foodstuffs Importing and Exporting Corporation (COFCO).[53]

Food safety

[edit]In the early 2000s, excessive pesticide residues, low food hygiene, unsafe additives, contamination with heavy metals and other contaminants and misuse of veterinary drugs had led to trade restrictions with some nations such as Japan, the United States, and the European Union.[54] These problems have also led to public outcry, such as in the melamine-tainted dog food scare and the carcinogenic-tainted seafood import restriction, leading to measures such as the "China-free" label.[55] In the milk scandal in China in 2008, many children became ill due to consumption of melamine-contaminated milk products, and a number of domestic dairy brands were found to contain melamine in their products, leading many countries to ban the import of Chinese dairy products.[56]

In 2011, About one tenth of China's farmland is contaminated with heavy metals, according to the Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People's Republic of China.[57]

Organic food products

[edit]China has developed a Green Food program where produce is certified for low pesticide input.[24] This has been articulated into Green food Grade A and Grade AA. This Green Food AA standard has been aligned with IFOAM international standards for organic farming and has formed the basis of the rapid expansion of organic agriculture in China.[24]

China's organic food production has experienced a rapid expansion in the 2010s, largely attributed to the booming domestic market due to the heightened food safety problem. In many cases, organic food production is organized by organic food companies leasing land from small scale farmers. Farmers' cooperatives and contract farming are also found to be common organizational structures of organic farming in China. The Chinese government has provided various policy and financial supports for the development of the organic sector. In recent years, non-certified organic production in diverse forms such as permaculture and natural farming is also emerging in China, often initiated by entrepreneurs or civil society organizations.[58]

See also

[edit]- History of China

- History of agriculture

- Population history of China

- History of canals in China

- Lettuce production in China

- China Green Food Development Center

- Peak water#China

- Wang Zhen (official)

- Franklin Hiram King

- Land use in the People's Republic of China

- Aquaculture in China

- Women in agriculture in China

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Liu, Li; Bestel, Sheahan; Shi, Jinming; Song, Yanhua; Chen, Xingcan (2013). "Paleolithic human exploitation of plant foods during the last glacial maximum in North China". PNAS. 110 (14): 5380–5385. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.5380L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1217864110. PMC 3619325. PMID 23509257.

- ^ The Cambridge World History Volume 2: A World With Agriculture 12,000 BCE-500 CE. p. 317.

- ^ a b c Liu, Li; Chen, Xingcan (2012). "Chapter 4: Domestication of Plants and Anfimals". The Archaeology of China: From the Late Paleolithic to the Early Bronze Age. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64432-7.

- ^ Zhao Zhijun (赵志军) (2004). 从兴隆沟遗址浮选结果谈中国北方旱作农业起源问题 [Discussion of the origin of dry farming using the results of flotation at Xinglonggou]. In (南京师范大学文博系) (ed.). 东亚考古 [East Asian Archaeology]. Wenwu Chubanshe. pp. 188–199.

- ^ Zong, Y; When, Z; Innes, JB; Chen, C; Wang, Z; Wang, H (2007). "Fire and flood management of coastal swamp enabled first rice paddy cultivation in east China". Nature. 449 (7161): 459–62. Bibcode:2007Natur.449..459Z. doi:10.1038/nature06135. PMID 17898767. S2CID 4426729.

- ^ Liu, Li; Chen, Xingcan (2012). "Chapter 6: Emergence of Social Inequality - the Middle Neolithic (5000-3000 BC)". The Archaeology of China: From the Late Paleolithic to the Early Bronze Age. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64432-7.

- ^ Ch'ien, Ssu-ma (2016). The Grand Scribe's Records, Volume X: Volume X: The Memoirs of Han China, Part 3. Indiana University Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0253020697. Retrieved August 6, 2019.

- ^ Paull, John (2011) "The making of an agricultural classic: Farmers of Forty Centuries or Permanent Agriculture in China, Korea and Japan, 1911–2011" Agricultural Sciences, 2(3), 175–180

- ^ Needham, Pt. 3, p. 271.

- ^ Needham, Pt. 2, p. 184.

- ^ Needham, Pt. 2, pp. 89, 110.

- ^ Needham, Pt. 2, p. 33.

- ^ Needham, Pt. 2, p. 110.

- ^ Bray 1984, p. 178.

- ^ Angus Maddison; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Development Centre (September 21, 2006). The world economy. Development Centre of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. pp. 20–. ISBN 978-92-64-02261-4. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ Community Development in Historical Perspectives: Tianjin from the Qing to the People's Republic of China. 2008. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-0-549-67543-3.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Organic Food and Farming in China: Top-down and Bottom-up Ecological Initiatives. Routledge. 2018. ISBN 978-1-13-857300-0.

- ^ The Dragon and the Elephant: Agricultural and Rural Reforms in China and India Edited by Ashok Gulati and Shenggen Fan (2007), Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 367

- ^ a b c Harrell, Stevan (2023). An Ecological History of Modern China. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295751719.

- ^ Peng Xizhe (彭希哲), "Demographic Consequences of the Great Leap Forward in China's Provinces," Population and Development Review 13, no. 4 (1987), 639–70.

For a summary of other estimates, please refer to this link - ^ OECD Review of Agricultural Policies – China. Oecd.org. Retrieved on 2012-02-14.

- ^ Critical Choices for China's Agricultural Policy. Ifpri.org (2002-12-20). Retrieved on 2012-02-14.

- ^ Louisa Lim The End of Agriculture in China. NPR.org. May 17, 2006. Retrieved on 2012-02-14.

- ^ a b c d Paull, J.,China's Organic Revolution, Journal of Organic Systems, 2(1) 1–11, 2007.

- ^ a b Shinn, David H.; Eisenman, Joshua (2023). China's Relations with Africa: a New Era of Strategic Engagement. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-21001-0.

- ^ "China - Agriculture, forestry, and fishing". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ Jianming, Cai (April 1, 2003). "Periurban Agriculture Development in China" (PDF). Urban Agriculture Magazine. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2007. Retrieved July 12, 2007.

- ^ Puette, Loren. "ChinaAg: Citrus Production". Archived from the original on October 24, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ^ Guo H.B. (2008). "Cultivation of lotus (Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. ssp. nucifera) and its utilization in China". Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 56 (3): 323–330. doi:10.1007/s10722-008-9366-2. S2CID 19718393.

- ^ Huang Hongwen (1987). "Lotus of China". Auburn University Lotus Project. Archived from the original on October 5, 2008. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ Terazono, Emiko (3 November 2014) "Chinese coffee trade full of beans", The Financial Times, page 17, Companies and markets, a similar article is available on the Internet with a subscription at [1], Accessed 7 November 2014

- ^ Yunnan coffee

- ^ Puette, Loren. "ChinaAg: Livestock (including Milk & Honey)". Archived from the original on October 24, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ^ 13-20 Number of Livestock. stats.gov.cn

- ^ Shi, Haitao; Parham, James F; Fan, Zhiyong; Hong, Meiling; Yin, Feng (2008). "Evidence for the massive scale of turtle farming in China". Oryx. 42: 147–150. doi:10.1017/S0030605308000562.

- ^ "From the U.S., a Future Supply of Livestock for China". The New York Times. Reuters. April 20, 2012. Retrieved April 21, 2012.

- ^ Beijing Official Website International Archived 2011-07-07 at the Wayback Machine. Ebeijing.gov.cn. Retrieved on 2012-02-14.

- ^ ITC Report: China's Agricultural Trade: Competitive Conditions and Effects on U.S. Exports; March 22, 2011. Usitc.gov (2011-03-22). Retrieved on 2012-02-14.

- ^ China Archived 2011-01-09 at the Wayback Machine. thehandthatfeedsus.org

- ^ Watts, Jonathan. "China to plough extra 20% into agricultural production amid fears that climate change will spark food crisis." Guardian News, 5 March 2009.

- ^ a b China production in 2018, by FAO

- ^ a b c Ching, Pao-Yu (2021). Revolution and counterrevolution : China's continuing class struggle since liberation (2nd ed.). Paris: Foreign languages press. p. 249. ISBN 978-2-491182-89-2. OCLC 1325647379.

- ^ a b 蔬菜流通环节将免征增值税 Archived 2013-02-10 at archive.today. 2011-12-28 [dead link]

- ^ 追踪菜市"跷跷板":缘何"卖菜难、买菜贵""+pindao+"_中国网络电视台 Archived March 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Nongjiale.cntv.cn (2011-05-09). Retrieved on 2012-02-14.

- ^ [Commentary: crack agricultural products "difficulty in selling" buy expensive "ills | Inside China]. February 14, 2012. Retrieved on 2012-02-14.[dead link]

- ^ [Comments: The key to eradicate the problem of poor sales of agricultural products and farmers by government - Finance News]. Agile-news.com (2011-11-18). Retrieved on 2012-02-14.[dead link]

- ^ a b Zhen, Liu (September 13, 2020). "Xi Jinping calls on science to solve the big problems choking China". South China Morning Post. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

He said that some of the main areas of research should be to overcome the agricultural sector's reliance on imported seed...

- ^ "Climate Change in China | Shangri-la Institute". waterschool.cn. Archived from the original on May 9, 2018. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ^ Zhang, Hongzhou. "Climate change threatens China's rice bowl". East Asia forum. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

- ^ China Drives Global Soybean Demand Archived January 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "China to become world's top farm products importer: researcher." Reuters, 6 November 2011.

- ^ Argument – Trends in Agricultural Policy Archived 2007-04-17 at the Wayback Machine. International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

- ^ Colin A. Carter and Xianghong Li Economic Reform and the Changing: Pattern of China's Agricultural Trade. Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of California Davis (July 1999)

- ^ Fengxia Dong and Helen H. Jensen Choices Article – Challenges for China's Agricultural Exports: Compliance with Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures. Choices Magazine. 1st Quarter 2007, Vol. 22(1). Retrieved on 2012-02-14.

- ^ "The new 'China-free' label". Chicago Tribune. July 9, 2007. Archived from the original on August 23, 2018. Retrieved July 9, 2007.

- ^ Zeng, Li; Zhou, Lijie; Pan, Po-Lin; Fowler, Gil (2018). "Coping with the milk scandal: A staged approach to crisis communication strategies during China's largest food safety crisis". Journal of Communication Management. 22 (4): 432–450. doi:10.1108/JCOM-11-2017-0133. ISSN 1363-254X. S2CID 150353957.

- ^ "Heavy metals pollute a tenth of China's farmland-report." Reuters, 6 November 2011.

- ^ Scott, Steffanie; Si, Zhenzhong; Schumilas, Theresa and Chen, Aijuan. (2018). Organic Food and Farming in China: Top-down and Bottom-up Ecological Initiatives New York: Routledge

Sources

[edit]- Books

- Bray, Francesca (1984), Science and Civilization in China 6

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Scott, Steffanie et al. (2018). Organic Food and Farming in China: Top-down and Bottom-up Ecological Initiatives. New York: Routledge.

Further reading

[edit]- Chai, Joseph C. H. An economic history of modern China (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2011).

- Perkins, Dwight H. Agricultural development in China, 1368-1968 (1969). pmline

- The Dragon and the Elephant: Agricultural and Rural Reforms in China and India Edited by Ashok Gulati and Shenggen Fan (2007), Johns Hopkins University Press

- Hsu, Cho-yun. Han Agriculture (Washington U. Press, 1980)

- Official Statistics from FAO

- Farmers, Mao, and Discontent in China: From the Great Leap Forward to the Present by Dongping Han, Monthly Review, November 2009

- The First National Agricultural Census in China (1997) National Bureau of Statistics of China

- Gale, Fred. (2013). Growth and Evolution in China's Agricultural Support Policies. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Scott, Steffanie; Si, Zhenzhong; Schumilas, Theresa and Chen, Aijuan. (2018). Organic Food and Farming in China: Top-down and Bottom-up Ecological Initiatives. New York. Routledge.

- Communiqués on Major Data of the Second National Agricultural Census of China (2006), No. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 National Bureau of Statistics of China. Copies on Internet Archive.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch