Cloaca Maxima

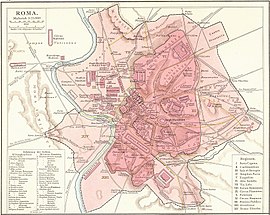

A map of central Rome during the time of the Roman Empire, showing the Cloaca Maxima in red | |

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| Coordinates | 41°53′20″N 12°28′49″E / 41.88889°N 12.48028°E |

|---|---|

The Cloaca Maxima (Latin: Cloāca Maxima [kɫɔˈaːka ˈmaksɪma], lit. 'Greatest Sewer') or, less often, Maxima Cloaca, is one of the world's earliest sewage systems. Its name is related to that of Cloacina, a Roman goddess.[1] Built during either the Roman Kingdom or early Roman Republic, it was constructed in Ancient Rome in order to drain local marshes and remove waste from the city. It carried effluent to the River Tiber, which ran beside the city. The sewer started at the Forum Augustum and ended at the Ponte Rotto and Ponte Palatino. It began as an open air canal, but it developed into a much larger sewer over the course of time. Agrippa renovated and reconstructed much of the sewer. This would not be the only development in the sewers, by the first century AD all eleven Roman aqueducts were connected to the sewer. After the Roman Empire fell the sewer still was used. By the 19th century, it had become a tourist attraction. Some parts of the sewer are still used today. During its heyday, it was highly valued as a sacred symbol of Roman culture and Roman engineering.

Construction and history

[edit]

According to tradition, it may have initially been constructed around 600 BC under the orders of the king of Rome, Tarquinius Priscus.[2][3] He ordered Etruscan workers and the plebeians to construct the sewers.[4] Before constructing the Cloaca Maxima, Priscus, and his son Tarquinius Superbus, worked to transform the land by the Roman forum from a swamp into a solid building ground, thus reclaiming the Velabrum.[5][6][7] In order to achieve this, they filled it up with 10-20,000 cubic meters of soil, gravel, and debris.[8][9][10]

At the beginning of the sewer's life it consisted of open-air channels lined up with bricks centered around a main pipe.[11][12] At this stage it might have had no roof. However, wooden holes spread throughout the sewer indicate that wooden bridges may have been built over it, which possibly functioned as a roof. Alternatively, the holes could have functioned as a support for the scaffolding needed to construct the sewer.[13] The Cloaca Maxima may also have originally been an open drain, formed from streams originating from three of the neighboring hills, that were channeled through the main Forum and then on to the Tiber.[3] As building space within the city became more valuable, the drain was gradually built over.[citation needed]

By the time of the late Roman Republic this sewer became the city's main storm drain.[14] It developed into a system 1,600 meters long.[15] By the second century BC, it had a 101 meter long canal which was covered up and expanded into a sewer.[16][17][18] Pliny the Elder, writing in the late 1st century, describes the early Cloaca Maxima as "large enough to allow the passage of a wagon loaded with hay."[19] Eventually, the sewer could not continue growing to keep up with the expanding city. Romans would discard waste through other openings rather than the sewers.[12] From 31 BC to 192 AD manholes could be used to access the sewer, which could be traversed by canal at this point. Manholes were decorated with marble reliefs, and canals were made of Roman concrete and flint.[20]

The eleven aqueducts which supplied water to Rome by the 1st century AD were finally channeled into the sewers after having supplied many of the public baths such as the Baths of Diocletian and the Baths of Trajan, as well as the public fountains, imperial palaces and private houses.[21][22] The continuous supply of running water helped to remove wastes and keep the sewers clear of obstructions. The best waters were reserved for potable drinking supplies, and the second quality waters would be used by the baths, the outfalls of which connected to the sewer network under the streets of the city.[23][24] The Cloaca Maxima was well maintained throughout the life of the Roman Empire and even today drains rainwater and debris from the center of town, below the ancient Forum, Velabrum, and the Forum Boarium. In more recent times, the remaining passages have been connected to the modern-day sewage system, mainly to cope with problems of backwash from the river.[citation needed]

After the fall of the Roman empire the Cloaca Maxima continued to be used. In the 1600s the Cardinal Chamberlain imposed a tax on residents of Rome in order to pay for the upkeep of the sewer.[13] By the time of the 1800s the Cloaca Maxima became popular as a tourist attraction. From 1842 to 1852 sections of the sewer were drained. Pietro Narducci, an Italian engineer was hired by the city of Rome to survey and restore the parts of the sewer by the Forum and the Torre dei Conti in 1862. In 1890 Otto Ludwig Richter, a German archaeologist created a map of the sewers.[25] These efforts renewed public interest in sanitation.[13]

Route

[edit]The Cloaca Maxima started at the Forum Augustum and followed the natural course of the suburbs of ancient Rome, which led between the Quirinal, Viminal, and Esquilline Hills. It also passed by the Forum of Nerva, the Arch of Janus, the Forum Boarium, the Basilica Aemilia, and the Forum Romanum, ending at the Velabrum.[26] The sewer's outfall was by the Ponte Rotto and Ponte Palatino. Some of this is still visible today.[20][27] The branches of the main sewer all appear to be 'official' drains that would have served public toilets, bathhouses and other public buildings.

Significance and effects

[edit]The extraordinary greatness of the Roman Empire manifests itself above all in three things: the aqueducts, the paved roads, and the construction of the drains.

The Cloaca Maxima was large enough for "wagons loaded with hay to pass" according to Strabo. It could transport one million pounds of waste, water, and unwanted goods, which were dumped into the streets, swamps, and rivers near Rome. They were all carried out to the Tiber River by the sewer. It used gutters to collect rainwater, rubbish, and spillage, and conduits to dispense up to ten cubic meters of water per second.[13][29] Vaults were closed with flat panels or rocks were used in the construction. This sewer used a trench wall to hold back sediments.[9]

Some of its water was still polluted, contaminating water many depended on for irrigation, swimming, bathing, and drinking.[14][30] The sewer reduced the number of mosquitos, thereby limiting the spread of malaria by draining marshy areas.[31] Animals, including rats, could find their way into the sewer.[15]

The Cloaca Maxima was a highly valued feat of engineering. It may have even been sacrosanct. Since the Romans viewed the movement of water to be sacred, the Cloaca Maxima may have had a religious significance. Aside from religious significance, the Cloaca Maxima may have been praised due to its age and its demonstration of engineering prowess.[32][33] Livy describes the sewer as:

Works for which the new splendor of these days has scarcely been able to produce a match.— Titus Livius, Titus Livius, The History of Rome, Book 1

The writer Pliny the Elder describes the Cloaca Maxima as an engineering marvel due to its ability to withstand floods of filthy waters for centuries. Cassiodorus, a Roman senator and scholar, praised the sewage system in Variae. The Cloaca Maxima was a symbol of Roman civilization, and its superiority to others.[34][35] Roman authors were not the only people to praise the Cloaca Maxima. British writer Henry James stated that it gave him: "the deepest and grimmest impression of antiquity I have ever received."

The system of Roman sewers was much imitated throughout the Roman Empire, especially when combined with copious supplies of water from Roman aqueducts. The sewer system in Eboracum—the modern-day English city of York—was especially impressive and part of it still survives.[36]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Narducci, Pietro (1889). Sulla fognatura della città di Roma: descrizione tecnica (in Italian). Forzani. Archived from the original on 13 December 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ Taylor, Rabun; Rinne, Katherine. Rome: an Urban History from Antiquity to the Present, by Rabun Taylor, Katherine Rinne, and Spiro Kostof (d), (Cambridge University Press: September 2016). pp. 8–9. Archived from the original on 9 December 2023. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Waters of Rome Journal - 4 - Hopkins.indd" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2007.

- ^ "Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, Book 1, chapter 56". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Archived from the original on 16 June 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Landart, Paula (2021). Finding Ancient Rome: Walks in the city. Paula Landart. p. 49.

- ^ Hunt, Alisa (2016). Reviving Roman Religion: Sacred Trees in the Roman World. Cambridge University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-110-715-354-7.

- ^ Littlewood, R. Joy (2006). A commentary on Ovid: Fasti book VI. OUP Oxford. p. 124. ISBN 978-019-927-134-4.

- ^ Izzet, Vedia (2007). The Archaeology of Etruscan Society. Cambridge University Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-110-732-091-8.

- ^ a b Garrett, Bradley; Galviz, Carlos; Dobraszczyk, Paul (2016). Global Undergrounds: Exploring Cities Within. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-178-023-611-7.

- ^ Viollet, Pierre-Louis (2017). Water Engineering in Ancient Civilizations: 5,000 Years of History. CRC Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-020-337-531-0.

- ^ Mehta-Jones, Shilpa (2005). Life in Ancient Rome. Crabtree Publishing Company. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7787-2034-8. Archived from the original on 13 December 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ a b Zimring, Carl; Rathje, William (2012). Encyclopedia of Consumption and Waste: The Social Science of Garbage. SAGE Publications. p. 802. ISBN 978-145-226-667-1.

- ^ a b c d Bianchi, Elisabetta. “Projecting and Building the Cloaca Maxima Archived 15 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine.” in E. Tamburrino (a cura di), Aquam Ducere II. Proceedings of the second international summer school “Water and the City: Hydraulic systems in the Roman Age” (Feltre, 24th-28th August 2015), Seren del Grappa (BL), 2018, pp. 177-204. (2018): n. pag. Print.

- ^ a b RAUTANEN, SANNA-LEENA, et al. “Sanitation, Water and Health Archived 14 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine.” Environment and History, vol. 16, no. 2, White Horse Press, 2010, pp. 173–94,

- ^ a b Aldrete, Gregory S. (2004). Daily Life in the Roman City: Rome, Pompeii and Ostia. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 15, 34–35, 97. ISBN 978-0-313-33174-9. Archived from the original on 13 December 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ Hopkins, John N. N. "The Cloaca Maxima and the Monumental Manipulation of water in Archaic Rome". Institute of the Advanced Technology in the Humanities. Web. 4/8/12

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita, 1.56

- ^ "RomaSegreta.it – Cloaca Maxima". RomaSegreta.it (in Italian). 12 May 2013. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ Plinius Secundus, Gaius, 23-79. (2014). Natural history. Harvard University Press. OCLC 967702213. Archived from the original on 13 December 2023. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Malacrino, Carmelo G. (2010). Constructing the Ancient World: Architectural Techniques of the Greeks and Romans. Getty Publications. pp. 172–173. ISBN 978-1-60606-016-2. Archived from the original on 13 December 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ Woods, Michael (2000). Ancient medicine: from sorcery to surgery Archived 9 December 2023 at the Wayback Machine. Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-0-8225-2992-7, p.81.

- ^ Lançon, Bertrand (2000). Rome in late antiquity: everyday life and urban change, AD 312-609 Archived 26 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-92975-2, p.13.

- ^ Herodian, Roman History, 5.8.9

- ^ "BBC Religion & Ethics - Exploring Rome's 'sacred sewers'". Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ^ Ebbo Demant: Vom Schleicher zum Springer. Hans Zehrer als politischer Publizist. Mainz 1971, S. 9.

- ^ "Cloaca Massima". www.romacittaeterna.it. Archived from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ "Eutropius, Abridgment of Roman History (Historiae Romanae Breviarium)". tertullian.org. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ Quilici, Lorenzo (2008): "Land Transport, Part 1: Roads and Bridges", in: Oleson, John Peter (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World, Oxford University Press, New York, ISBN 978-0-19-518731-1, pp. 551–579 (552)

- ^ Eslamian, Saeid (2018). Handbook of Engineering Hydrology. CRC Press. p. 186. ISBN 9781466552364. Archived from the original on 9 December 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ Zeldovich, Lina (19 November 2021). The Other Dark Matter: The Science and Business of Turning Waste into Wealth and Health. University of Chicago Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-0-226-81422-3. Archived from the original on 13 December 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ Butler, David; Digman, Chris; Makropoulos, Christos; Davies, John (2018). Urban Drainage. CRC Press. ISBN 978-149-875-061-5.

- ^ Magnusson, Roberta J. (2012). "Katherine Wentworth Rinne . The Waters of Rome: Aqueducts, Fountains, and the Birth of the Baroque City . New Haven: Yale University Press. 2010. Pp. X, 262. $65.00". The American Historical Review. 117 (3): 954–955. doi:10.1086/ahr.117.3.954.

- ^ "Roman antiquities 3". www.the-romans.eu. Archived from the original on 30 December 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ Bradley, Mark (26 July 2012). Rome, Pollution and Propriety: Dirt, Disease and Hygiene in the Eternal City from Antiquity to Modernity. Cambridge University Press. pp. 81–105. ISBN 978-1-139-53657-8. Archived from the original on 13 December 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ Laporte, Dominique (22 February 2002). History of Shit. MIT Press. pp. 13–15, 47, 78. ISBN 978-0-262-62160-1. Archived from the original on 13 December 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ Darvill, Timothy, Stamper, Paul and Timby, Jane (2002). England: an Oxford archaeological guide to sites from earliest times to AD 1600 Archived 9 December 2023 at the Wayback Machine. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-284101-8, pp. 162-163.

External links

[edit]- Cloaca Maxima: article in Platner's Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome

- Pictures taken from inside the Cloaca Maxima

- Aquae Urbis Romae: The Waters of the City of Rome, Katherine W. Rinne

- The Waters of Rome: "The Cloaca Maxima and the Monumental Manipulation of Water in Archaic Rome" by John N. N. Hopkins

- Rome: Cloaca Maxima Archived 20 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Lucentini, M. (31 December 2012). The Rome Guide: Step by Step through History's Greatest City. Interlink. ISBN 9781623710088.

![]() Media related to Cloaca Maxima at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cloaca Maxima at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Aqua Claudia | Landmarks of Rome Cloaca Maxima | Succeeded by Baths of Agrippa |

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch