Convoy PQ 9/10

| Second World War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Arctic Convoys | |||||||

The Norwegian and the Barents seas, site of the Arctic convoys | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| | | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Hans-Jürgen Stumpff Hermann Böhm | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10 Freighters 10 Escorts (in relays) | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| No losses | No losses | ||||||

Convoys PQ 9/10 (1–10 February 1942) was an Arctic convoy sent from Great Britain via Iceland by the Western Allies to aid the Soviet Union during the Second World War. The departure of Convoy PQ 9 on 17 January had been delayed after the Admiralty received reports of a sortie by the German battleship Tirpitz. The ships arrived in Murmansk without loss after an uneventful voyage.

Background[edit]

Lend-lease[edit]

After Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the USSR, began on 22 June 1941, the UK and USSR signed an agreement in July that they would "render each other assistance and support of all kinds in the present war against Hitlerite Germany".[1] Before September 1941 the British had dispatched 450 aircraft, 22,000 long tons (22,000 t) of rubber, 3,000,000 pairs of boots and stocks of tin, aluminium, jute, lead and wool. In September British and US representatives travelled to Moscow to study Soviet requirements and their ability to meet them. The representatives of the three countries drew up a protocol in October 1941 to last until June 1942 and to agree new protocols to operate from 1 July to 30 June of each following year until the end of Lend-Lease. The protocol listed supplies, monthly rates of delivery and totals for the period.[2]

The first protocol specified the supplies to be sent but not the ships to move them. The USSR turned out to lack the ships and escorts and the British and Americans, who had made a commitment to "help with the delivery", undertook to deliver the supplies for want of an alternative. The main Soviet need in 1941 was military equipment to replace losses because, at the time of the negotiations, two large aircraft factories were being moved east from Leningrad and two more from Ukraine. It would take at least eight months to resume production, until when, aircraft output would fall from 80 to 30 aircraft per day. Britain and the US undertook to send 400 aircraft a month, at a ratio of three bombers to one fighter (later reversed), 500 tanks a month and 300 Bren gun carriers. The Anglo-Americans also undertook to send 42,000 long tons (43,000 t) of aluminium and 3, 862 machine tools, along with sundry raw materials, food and medical supplies.[2]

British grand strategy[edit]

The growing German air strength in Norway and increasing losses to convoys and their escorts, led Rear-Admiral Stuart Bonham Carter, commander of the 18th Cruiser Squadron, Admiral sir Admiral John Tovey, Commander in Chief Home Fleet and Admiral Sir Dudley Pound the First Sea Lord, the professional head of the Royal Navy, unanimously to advocate the suspension of Arctic convoys during the summer months. The small number of Russian ships available to meet Arctic convoys, losses inflicted by Luftflotte 5 based in Norway and the presence of the German battleship Tirpitz in Norway from early 1942, had led to ships full of supplies to Russia becoming stranded at Iceland and empty and damaged ships waiting at Murmansk.[3]

Bletchley Park[edit]

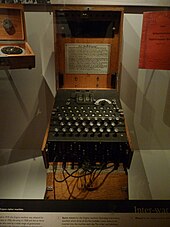

The British Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) based at Bletchley Park housed a small industry of code-breakers and traffic analysts. By June 1941, the German Enigma machine Home Waters (Heimish) settings used by surface ships and U-boats could quickly be read. On 1 February 1942, the Enigma machines used in U-boats in the Atlantic and Mediterranean were changed but German ships and the U-boats in Arctic waters continued with the older Heimish (Hydra from 1942, Dolphin to the British). By mid-1941, British Y-stations were able to receive and read Luftwaffe W/T transmissions and give advance warning of Luftwaffe operations. In 1941, naval Headache personnel with receivers to eavesdrop on Luftwaffe wireless transmissions were embarked on warships..[4][5]

B-Dienst[edit]

The rival German Beobachtungsdienst (B-Dienst, Observation Service) of the Kriegsmarine Marinenachrichtendienst (MND, Naval Intelligence Service) had broken several Admiralty codes and cyphers by 1939, which were used to help Kriegsmarine ships elude British forces and provide opportunities for surprise attacks. From June to August 1940, six British submarines were sunk in the Skaggerak using information gleaned from British wireless signals. In 1941, B-Dienst read signals from the Commander in Chief Western Approaches informing convoys of areas patrolled by U-boats, enabling the submarines to move into "safe" zones.[6] B-Dienst had broken Naval Cypher No 3 in February 1942 and by March was reading up to 80 per cent of the traffic, which continued until 15 December 1943. By coincidence, the British lost access to the Shark cypher and had no information to send in Cypher No 3 which might compromise Ultra.[7] In early September, Finnish Radio Intelligence deciphered a Soviet Air Force transmission which divulged the convoy itinerary, which was forwarded it to the Germans.[8]

Arctic Ocean[edit]

Between Greenland and Norway are some of the most stormy waters of the world's oceans, 890 mi (1,440 km) of water under gales full of snow, sleet and hail.[9] The cold Arctic water was met by the Gulf Stream, warm water from the Gulf of Mexico, which became the North Atlantic Drift. Arriving at the south-west of England the drift moves between Scotland and Iceland; north of Norway the drift splits. One stream bears north of Bear Island to Svalbard and a southern stream follows the coast of Murmansk into the Barents Sea. The mingling of cold Arctic water and warmer water of higher salinity generates thick banks of fog for convoys to hide in but the waters drastically reduced the effectiveness of ASDIC as U-boats moved in waters of differing temperatures and density.[9]

In winter, polar ice can form as far south as 50 mi (80 km) off the North Cape and in summer it can recede to Svalbard. The area is in perpetual darkness in winter and permanent daylight in the summer and can make air reconnaissance almost impossible.[9] Around the North Cape and in the Barents Sea the sea temperature rarely rises about 4° Celsius and a man in the water will die unless rescued immediately.[9] The cold water and air makes spray freeze on the superstructure of ships, which has to be removed quickly to avoid the ship becoming top-heavy. Conditions in U-boats were, if anything, worse the boats having to submerge in warmer water to rid the superstructure of ice. Crewmen on watch were exposed to the elements, oil lost its viscosity; nuts froze and sheared off bolts. Heaters in the hull wee too demanding of current and could not be run continuously.[10]

Prelude[edit]

Kriegsmarine[edit]

German naval forces in Norway were commanded by Hermann Böhm, the Kommandierender Admiral Norwegen. In 1941, British Commando raids on the Lofoten Islands (Operation Claymore and Operation Anklet) led Adolf Hitler to order U-boats to be transferred from the Battle of the Atlantic to Norway and on 24 January 1942, eight U-boats were ordered to the area of Iceland–Faroes–Scotland. Two U-boats were based in Norway in July 1941, four in September, five in December and four in January 1942.[11] By mid-February twenty U-boats were anticipated in the region, with six based in Norway, two in Narvik or Tromsø, two at Trondheim and two at Bergen. Hitler contemplated establishing a unified command but decided against it. The German battleship Tirpitz arrived at Trondheim on 16 January, the first ship of a general move of surface ships to Norway. British convoys to Russia had received little attention since they averaged only eight ships each and the long Arctic winter nights negated even the limited Luftwaffe effort that was available.[12]

Luftflotte 5[edit]

In mid-1941, Luftflotte 5 (Air Fleet 5) had been re-organised for Operation Barbarossa with Luftgau Norwegen (Air Region Norway) was headquartered in Oslo. Fliegerführer Stavanger (Air Commander Stavanger) the centre and north of Norway, Jagdfliegerführer Norwegen (Fighter Leader Norway) commanded the fighter force and Fliegerführer Kerkenes (Oberst [colonel] Andreas Nielsen) in the far north had airfields at Kirkenes and Banak. The Air Fleet had 180 aircraft, sixty of which were reserved for operations on the Karelian Front against the Red Army. The distance from Banak to Archangelsk was 560 mi (900 km) and Fliegerführer Kerkenes had only ten Junkers Ju 88 bombers of Kampfgeschwader 30, thirty Junkers Ju 87 Stuka dive-bombers ten Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighters of Jagdgeschwader 77, five Messerschmitt Bf 110 heavy fighters of Zerstörergeschwader 76, ten reconnaissance aircraft and an anti-aircraft battalion.[13]

Sixty aircraft were far from adequate in such a climate and terrain where "there is no favourable season for operations". The emphasis of air operations changed from army support to anti-shipping operations as Allied Arctic convoys became more frequent.[13] Hubert Schmundt, the Admiral Nordmeer noted gloomily on 22 December 1941 that the number long-range reconnaissance aircraft was exiguous and from 1 to 15 December only two Ju 88 sorties had been possible. After the Lofoten Raids, Schmundt wanted Luftflotte 5 to transfer aircraft to northern Norway but its commander, Generaloberst Hans-Jürgen Stumpff, was reluctant to deplete the defences of western Norway. Despite this some air units were transferred, a catapult ship (Katapultschiff), MS Schwabenland, was sent to northern Norway and Heinkel He 115 floatplane torpedo-bombers, of Küstenfliegergruppe 1./406 was transferred to Sola. By the end of 1941, III Gruppe, KG 30 had been transferred to Norway and in the new year, another Staffel of Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Kondor reconnaissance bombers from Kampfgeschwader 40 (KG 40) had arrived. Luftflotte 5 was also expecting a Gruppe of three Staffeln of Heinkel He 111 torpedo-bombers.[14]

Arctic convoys[edit]

In October 1941, the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, made a commitment to send a convoy to the Arctic ports of the USSR every ten days and to deliver 1,200 tanks a month from July 1942 to January 1943, followed by 2,000 tanks and another 3,600 aircraft in excess of those already promised.[1][a] The first convoy was due at Murmansk around 12 October and the next convoy was to depart Iceland on 22 October. A motley of British, Allied and neutral shipping loaded with military stores and raw materials for the Soviet war effort would be assembled at Hvalfjörður (Hvalfiord) in Iceland, convenient for ships from both sides of the Atlantic.[16] By late 1941, the convoy system used in the Atlantic had been established on the Arctic run; a convoy commodore ensured that the ships' masters and signals officers attended a briefing to make arrangements for the management of the convoy, which sailed in a formation of long rows of short columns. The commodore was usually a retired naval officer or a Royal Naval Reserveist and would be aboard one of the merchant ships (identified by a white pendant with a blue cross). The commodore was assisted by a Naval signals party of four men, who used lamps, semaphore flags and telescopes to pass signals in code.[17]

In large convoys, the commodore was assisted by vice- and rear-commodores with whom he directed the speed, course and zig-zagging of the merchant ships and liaised with the escort commander.[17][b] By the end of 1941, 187 Matilda II and 249 Valentine tanks had been delivered, comprising 25 per cent of the medium-heavy tanks in the Red Army and 30 to 40 per cent of the medium-heavy tanks defending Moscow. In December 1941, 16 per cent of the fighters defending Moscow were Hurricanes and Tomahawks from Britain; by 1 January 1942, 96 Hurricane fighters were flying in the Soviet Air Forces (Voyenno-Vozdushnye Sily, VVS). The British supplied radar apparatuses, machine tools, ASDIC and other commodities.[18] During the summer months, convoys went as far north as 75 N latitude then south into the Barents Sea and to the ports of Murmansk in the Kola Inlet and Archangel in the White Sea. In winter, due to the polar ice expanding southwards, the convoy route ran closer to Norway.[19] The voyage was between 1,400 and 2,000 nmi (2,600 and 3,700 km; 1,600 and 2,300 mi) each way, taking at least three weeks for a round trip.[20]

Ships[edit]

Convoy PQ 9/10 comprised ten ships; three British, four Soviet, one US, one Norwegian and one of Panamanian registry. For the first part of the voyage the convoy was escorted by three trawlers from Iceland, then the light cruiser HMS Nigeria and the destroyers HMS Faulknor and HMS Intrepid, close escort was by the Norwegian armed whalers HNoMS Hav and HNoMS Shika. The escorts were joined from Kola on 7 February by the Royal Navy minesweepers HMS Britomart and HMS Sharpshooter.[21]

Voyage[edit]

Convoy PQ 9/10 sailed from Scotland for Iceland in mid-January, where it was joined by ships from the Americas. Convoy PQ 10 was due to follow, but delays and failures meant that only Trevorian, sailed for Reykjavik, on 26 January 1942. The departure of Convoy PQ 9 on 17 January had been delayed after the Admiralty received reports of a sortie by the German battleship Tirpitz.[22] It was decided that Trevorian would join the ships of Convoy PQ 9, rather than wait for Convoy PQ 10 to be re-formed. The combined convoy of ten ships sailed from Reykjavik on 1 February and went undetected by German aircraft or U-boats in the continuous darkness of the polar night and arrived safely at Murmansk on 10 February.[23]

Ships[edit]

Convoy PQ 9/10[edit]

| Name | Flag | Tonnage (GRT) | Pos'n[c] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atlantic (1939) | 5,414 | 39 | ||

| El Lago (1920) | 4,221 | 20 | ||

| Empire Selwyn (1941) | 7,167 | 41 | Reykjavik 31 January, sailed 1 February | |

| Friedrich Engels (1930) | 3,972 | 30 | ||

| Ijora (1921) | 2,815 | 21 | ||

| Noreg (1931) | 7,605 | 31 | Tanker[26] | |

| Revolutsioner (1936) | 2,900 | 36 | ||

| Tbilisi (1912) | 7,169 | 12 | ||

| West Nohno (1919) | 5,769 | 19 |

(PQ 10)[edit]

| Name | Flag | (GRT) | Pos'n[d] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trevorian | 4,599 | 20 | Sole ship of Convoy PQ 10, combined with Convoy PQ 9 as Convoy PQ 9/10 |

Escorts[edit]

| Ship | Flag | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Local escorts[e] | Trawler | Escort 1–5 February | |

| HMS Britomart | Minesweeper | Escort 7–10 February | |

| HMS Faulknor | Destroyer | Escort 5–10 February | |

| HNoMS Hav | Whaler | Escort 1–10 February | |

| HMS Intrepid | Destroyer | Escort 5–10 February | |

| HMS Nigeria | Light cruiser | Escort 5–8 February | |

| HMS Sharpshooter | Minesweeper | Escort 7–10 February | |

| HNoMS Shika | Whaler | Escort 1–10 February |

Notes[edit]

- ^ In October 1941, the unloading capacity of Archangel was 300,000 long tons (300,000 t), Vladivostok (Pacific Route) 140,000 long tons (140,000 t) and 60,000 long tons (61,000 t) in the Persian Gulf (for the Persian Corridor route) ports.[15]

- ^ Code-books were carried in a weighted bag which was to be dumped overboard to prevent capture.[17]

- ^ Convoys had a standard formation of short columns, number 1 to port in the direction of travel. Each position in the column was numbered; 11 was the first ship in column 1 and 12 was the next ship in the column; 21 was the first ship in column 2.[25]

- ^ Convoys had a standard formation of short columns, number 1 to port in the direction of travel. Each position in the column was numbered; 11 was the first ship in column 1 and 12 was the next ship in the column; 21 was the first ship in column 2.[25]

- ^ Names unknown.[27]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ a b Woodman 2004, p. 22.

- ^ a b Hancock & Gowing 1949, pp. 359–362.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Macksey 2004, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Hinsley 1994, pp. 141, 145–146.

- ^ Kahn 1973, pp. 238–241.

- ^ Budiansky 2000, pp. 250, 289.

- ^ FIB 1996.

- ^ a b c d Claasen 2001, pp. 195–197.

- ^ Paterson 2016, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Rahn 2001, p. 348.

- ^ Claasen 2001, pp. 190–192, 194.

- ^ a b Claasen 2001, pp. 188–189.

- ^ Claasen 2001, pp. 189–194.

- ^ Howard 1972, p. 44.

- ^ Woodman 2004, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Woodman 2004, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Edgerton 2011, p. 75.

- ^ Roskill 1962, p. 119.

- ^ Butler 1964, p. 507.

- ^ Rohwer & Hümmelchen 2005, p. 140; Ruegg & Hague 1993, p. 26.

- ^ Roskill 1962, p. 116.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b Ruegg & Hague 1993, p. 25.

- ^ a b Ruegg & Hague 1993, p. 31, inside front cover.

- ^ Woodman 2004, p. 60.

- ^ Ruegg & Hague 1993, p. 26.

References[edit]

Books[edit]

- Boog, H.; Rahn, W.; Stumpf, R.; Wegner, B. (2001). The Global War: Widening of the Conflict into a World War and the Shift of the Initiative 1941–1943. Germany in the Second World War. Vol. VI. Translated by Osers, E.; Brownjohn, J.; Crampton, P.; Willmot, L. (Eng trans. Oxford University Press, London ed.). Potsdam: Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt (Research Institute for Military History). ISBN 0-19-822888-0.

- Rahn, W. "Part III The War at Sea in the Atlantic and in the Arctic Ocean. III. The Conduct of the War in the Atlantic and the Coastal Area (b) The Third Phase, April–December 1941: The Extension of the Areas of Operations". In Boog et al. (2001).

- Budiansky, S. (2000). Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War II. New York: The Free Press (Simon & Schuster). ISBN 0-684-85932-7 – via Archive Foundation.

- Butler, J. R. M. (1964). Grand Strategy: June 1941 – August 1942 (Part II). History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. III. London: HMSO. OCLC 504770038.

- Claasen, A. R. A. (2001). Hitler's Northern War: The Luftwaffe's Ill-fated Campaign, 1940–1945. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-1050-2.

- Edgerton, D. (2011). Britain's War Machine: Weapons, Resources and Experts in the Second World War. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9918-1.

- Hancock, W. K.; Gowing, M. M. (1949). Hancock, W. K. (ed.). British War Economy. History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Civil Series. London: HMSO. OCLC 630191560.

- Hinsley, F. H. (1994) [1993]. British Intelligence in the Second World War: Its Influence on Strategy and Operations. History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series (2nd rev. abr. ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-630961-7.

- Howard, M. (1972). Grand Strategy: August 1942 – September 1943. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. IV. London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-630075-1 – via Archive Foundation.

- Kahn, D. (1973) [1967]. The Codebreakers: The Story of Secret Writing (10th abr. Signet, Chicago ed.). New York: Macmillan. LCCN 63-16109. OCLC 78083316.

- Macksey, K. (2004) [2003]. The Searchers: Radio Intercept in two World Wars (Cassell Military Paperbacks ed.). London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-36651-4.

- Paterson, Lawrence (2016). Steel and Ice: The U-Boat Battle in the Arctic and Black Sea 1941–45. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-258-4.

- Rohwer, Jürgen; Hümmelchen, Gerhard (2005) [1972]. Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two (3rd rev. ed.). London: Chatham. ISBN 1-86176-257-7.

- Roskill, S. W. (1962) [1956]. The Period of Balance. History of the Second World War: The War at Sea 1939–1945. Vol. II (3rd impression ed.). London: HMSO. OCLC 174453986. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014.

- Ruegg, Bob; Hague, Arnold (1993) [1992]. Convoys to Russia (2nd rev. exp. pbk. ed.). Kendal: World Ship Society. ISBN 978-0-905617-66-4.

- Woodman, Richard (2004) [1994]. Arctic Convoys 1941–1945. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5752-1.

Websites[edit]

- "Birth of Radio Intelligence in Finland and its Developer Reino Hallamaa". Pohjois–Kymenlaakson Asehistoriallinen Yhdistys Ry (North-Karelia Historical Association Ry) (in Finnish). 1996. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

Further reading[edit]

- Blair, Clay (1996). Hitler's U-Boat War: The Hunters 1939–42. Vol. I. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-35260-8.

- Kemp, Paul (1993). Convoy! Drama in Arctic Waters. London: Arms and Armour Press. ISBN 1-85409-130-1 – via Archive Foundation.

- Schofield, Bernard (1964). The Russian Convoys. London: BT Batsford. OCLC 906102591 – via Archive Foundation.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch