Criticism of the alcohol industry

The alcohol industry, also known as Big Alcohol, is the segment of the commercial drink industry that is involved in the manufacturing, distribution, and sale of alcoholic beverages.[1] The industry has been criticised in the 1990s for deflecting attention away from the problems associated with alcohol use.[2] The alcohol industry has also been criticised for being unhelpful in reducing the harm of alcohol.[3]

The World Bank works with and invests in alcohol industry projects when positive effects with regard to public health concerns and social policy are demonstrated.[4] Alcohol industry-sponsored education to reduce the harm of alcohol, actually results in an increase in the harm of alcohol. As a result, it has been recommended that the alcohol industry does not become involved in alcohol policy or educational programs.[5]

In the United Kingdom, the New Labour government took the view that working with the alcohol industry to reduce harm was the most effective strategy. However, alcohol-related harms and alcohol use disorders have increased.[6] The alcohol industry has been accused of exaggerating the health benefits of alcohol which is regarded as a potentially dangerous recreational drug with potentially serious adverse effects on health.[7]

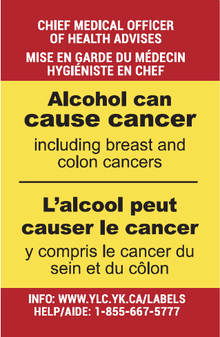

Since ethanol is classified as a Class I carcinogen, and there is no safe dose of alcohol; the alcohol industry is considered one of the main contributors to the formation of civilization or lifestyle diseases. The alcohol industry has tried to actively mislead the public about the risk of cancer due to alcohol consumption,[8] in addition to campaigning to remove laws that require alcoholic beverages to have cancer warning labels.[9]

A 2019 survey conducted by the American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR) showed that only 45% of Americans were aware of the associated risk of cancer due to alcohol consumption, up from 39% in 2017.[10] The AICR believes that alcohol-related advertisements about the healthy cardiovascular benefits of modest alcohol overshadow messages about the increased cancer risks.[10]

Cancer

[edit]

Since ethanol is classified as a Class I carcinogen, and there is no safe dose of alcohol; the alcohol industry is considered one of the main contributors to the formation of civilization or lifestyle diseases. The alcohol industry has tried to actively mislead the public about the risk of cancer due to alcohol consumption,[8] in addition to campaigning to remove laws that require alcoholic beverages to have cancer warning labels (cf. Northern Territories Alcohol Labels Study).[9]

Target marketing

[edit]Youth

[edit]The alcohol industry has tried to market its products to appeal to impressionable youth and young adults.[11]

LGBT marketing

[edit]

The alcohol industry has marketed products directly to the LGBT+ community. In 2010, of the sampled parades that listed sponsors, 61% of the prides were sponsored by the alcohol industry.[12]

The LGBT+ community has historically suffered from higher levels of substance abuse than non-LGBT+ individuals. As of 2013, LGBT+ youth struggle with higher levels of alcohol usage than their non-LGBT+ peers, a pattern previously seen in 1998, 2003, and 2008 data.[13]

Pinkwashing

[edit]Drinking alcoholic beverages increases the risk for breast cancer. Several studies indicate that the use of marketing by the alcohol industry to associate their products with breast cancer awareness campaigns, known as pinkwashing, is misleading and potentially harmful. Studies have found that this marketing strategy can increase perceptions of product healthfulness and social responsibility, leading to more favorable brand attitudes and reduced support for alcohol policies that could reduce consumption. However, there is evidence that informing the public about the contradictions and dangers of this practice can increase perceptions of misleadingness and support for measures like requiring alcohol-cancer warning labels. Overall, the research suggests that pinkwashed alcohol marketing exploits women's health concerns for commercial gain and undermines public health efforts to reduce alcohol-related harms.[14][15][16][17]

See also

[edit]- Alcoholic beverage industry in Europe

- Alcohol use disorder

- Alcohol advertising

- Alcohol education

- Alcohol and health

- Temperance movement

References

[edit]- ^ "Big Alcohol Myths". IOGT International. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ DeJong, W.; Wallack, L. (1992). "The role of designated driver programs in the prevention of alcohol-impaired driving: a critical reassessment". Health Education Quarterly. 19 (4): 429–42, discussion 443–5. doi:10.1177/109019819201900407. PMID 1452445.

- ^ Casswell, S.; Thamarangsi, T. (Jun 2009). "Reducing harm from alcohol: call to action". Lancet. 373 (9682): 2247–57. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60745-5. PMID 19560606. S2CID 44806354.

- ^ Room, R.; Jernigan, D. (Dec 2000). "The ambiguous role of alcohol in economic and social development". Addiction. 95 Suppl 4 (12s4): S523–35. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.95.12s4.6.x. PMID 11218349.

- ^ Anderson, P. (May 2009). "Global alcohol policy and the alcohol industry". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 22 (3): 253–7. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e328329ed75. PMID 19262384. S2CID 25267576.

- ^ Anderson, P. (Oct 2007). "A safe, sensible and social AHRSE: New Labour and alcohol policy". Addiction. 102 (10): 1515–21. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02000.x. PMID 17854326.

- ^ Sellman, D.; Connor, J.; Robinson, G.; Jackson, R. (2009). "Alcohol cardio-protection has been talked up". New Zealand Medical Journal. 122 (1303): 97–101. PMID 19851424.

- ^ a b Petticrew M, Maani Hessari N, Knai C, Weiderpass E, et al. (2018). "How alcohol industry organisations mislead the public about alcohol and cancer" (PDF). Drug and Alcohol Review. 37 (3): 293–303. doi:10.1111/dar.12596. PMID 28881410. S2CID 892691.[1]

- ^ a b Chaudhuri, Saabira (9 February 2018). "Lawmakers, Alcohol Industry Tussle Over Cancer Labels on Booze". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ a b "2019 AICR Cancer Risk Awareness Survey" (PDF). AICR 2019 Cancer Risk Awareness Survey. 2019.

- ^ Padon, Alisa A.; Rimal, Rajiv N.; Siegel, Michael; DeJong, William; Naimi, Timothy S.; JernFigan, David H. (5 February 2018). "Alcohol Brand Use of Youth-Appealing Advertising and Consumption by Youth and Adults". Journal of Public Health Research. 7 (1): jphr.2018.1269. doi:10.4081/jphr.2018.1269.

- ^ Spivey, Jasmine (February 2018). "Tobacco Policies and Alcohol Sponsorship at Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Pride Festivals: Time for Intervention". American Journal of Public Health. 108 (2): 187–188. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.304205. PMC 5846596. PMID 29320286.

- ^ Fish, Jessica (November 2017). "Are alcohol-related disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth decreasing?". Addiction. 112 (11): 1931–1941. doi:10.1111/add.13896. PMC 5633511. PMID 28678415.

- ^ Greene, NK; Rising, CJ; Seidenberg, AB; Eck, R; Trivedi, N; Oh, AY (May 2023). "Exploring correlates of support for restricting breast cancer awareness marketing on alcohol containers among women". The International Journal on Drug Policy. 115: 104016. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2023.104016. PMC 10593197. PMID 36990013.

- ^ Atkinson, AM; Meadows, BR; Sumnall, H (8 February 2024). "'Just a colour?': Exploring women's relationship with pink alcohol brand marketing within their feminine identity making". The International Journal on Drug Policy. 125: 104337. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2024.104337. PMID 38335868.

- ^ Hall, MG; Lee, CJY; Jernigan, DH; Ruggles, P; Cox, M; Whitesell, C; Grummon, AH (May 2024). "The impact of "pinkwashed" alcohol advertisements on attitudes and beliefs: A randomized experiment with US adults". Addictive Behaviors. 152: 107960. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2024.107960. PMC 10923020. PMID 38309239.

- ^ Mart, S; Giesbrecht, N (October 2015). "Red flags on pinkwashed drinks: contradictions and dangers in marketing alcohol to prevent cancer". Addiction. 110 (10): 1541–8. doi:10.1111/add.13035. PMID 26350708.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch