Cromford Mill

Cromford Mill | |

| Cotton | |

|---|---|

| Spinning Mill (Water frame) | |

| Structural system | Stone |

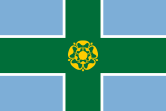

| Location | Cromford, Derbyshire |

| Owner | Arkwright |

| Coordinates | 53°06′32″N 1°33′22″W / 53.1090°N 1.5560°W |

| Construction | |

| Built | 1772 |

| Employees | 200 |

| Floor count | 5 |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Cromford Mill |

| Designated | 22 June 1950 |

| Reference no. | 1248010[1] |

Cromford Mill is the world's first water-powered cotton spinning mill, developed by Richard Arkwright in 1771 in Cromford, Derbyshire, England. The mill structure is classified as a Grade I listed building.[1] It is now the centrepiece of the Derwent Valley Mills UNESCO World Heritage Site, and is a multi-use visitor centre with shops, galleries, restaurants and cafes.

History

[edit]Following the invention of the flying shuttle for weaving cotton in 1733, the demand for spun cotton increased enormously in England. Machines for carding and spinning had already been developed but were inefficient. Spun cotton was also produced by means of the spinning jenny but was insufficiently strong to form the warp of a fabric, for which it was the practice to use linen thread, producing a type of cloth known as fustian. In 1769, Richard Arkwright patented a water frame to use the extra power of a water mill after he had set up a horse-powered mill in Nottingham.[2]

He chose the site at Cromford because it had year-round supply of warm water from the Cromford Sough which drained water from nearby Wirksworth lead mines, together with Bonsall Brook. Here he built a five-storey mill, with the backing of Jedediah Strutt (whom he met in a Nottingham bank via Ichabod Wright), Samuel Need and John Smalley. Starting from 1772, he ran the mills day and night with two twelve-hour shifts.[3]

He started with 200 workers, more than the locality could provide, so he built housing for them nearby, one of the first manufacturers to do so.[4] Most of the employees were women and children, the youngest being only seven years old. Later, the minimum age was raised to ten and the children were given six hours of education a week, so that they could do the record-keeping that their illiterate parents could not.

A large part of the village was built to house the mill workers. Stuart Fisher states that these are now considered to be "the first factory housing development in the world".[5] Employees were provided with shops, pubs, chapels and a school.

The gate to Cromford Mill was shut at precisely 6 am and 6 pm every day, and any worker who failed to get through it not only lost a day's pay but also was fined another day's pay.

Cromford dollars

[edit]

In 1801 and 1802, during a national shortage of silver, Spanish real coins were overstamped for use as coinage at Cromford.[6]

Closure and further use

[edit]The cotton mill ceased operation in the 19th century and the buildings were used for other purposes, finally a dyeing plant. In 1979, the Grade I listed site was bought by the Arkwright Society, who began the long task of restoring it to its original state.

The importance of this site is not that it was the first but that it was the first successful cotton spinning factory. It showed unequivocally the way ahead and was widely emulated.[citation needed]

World Heritage Site

[edit]The Cromford mill complex, owned and being restored by the Arkwright Society,[7] was declared by Historic England as "one of the country’s 100 irreplaceable sites".[8] In 2018, the "Cromford Mills Creative Cluster and World Heritage Site Gateway Project" was listed as a finalist for the "Best Major Regeneration of a Historic Building or Place" in the Historic England Angel Awards.[8]

In 2019, the Arkwright Society employed 100 people;[7] by that time, the restoration expenditure had reached £48 million.[9]

The mill and other buildings are open to the public every day,[10] and has attracted visitors from all over the world. Facilities include a visitors' centre, shops and a café.[11]

The nearby Cromford Canal towpath to High Peak Junction, and onwards towards Ambergate, is listed as a Biological Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI).[12]

In 2024 the site has been used as a venue for BBC One's Antiques Roadshow.[13][14]

Restoration

[edit]Condition in 1995

[edit]The 1771 building had been reduced by two storeys in 1929. Access was forbidden due to the toxic residue from the 20th-century paintmaking usage; the later tank with its toxic sediment obscured the foundations of the 1775 mill and the breast-shot waterwheel chamber. Only one remaining mill building was usable and suitable for guided tours.

- The original 1771 mill seen on the approach along Mill Road from the village

- The first mill viewed from the yard in 1995

- The tank over the waterwheel chamber

- The usable mill building undergoing work to replace many stone lintels and reinstate the original Georgian windows

Restoration in progress 2009

[edit]- Existing three of five storeys showing the extent of the original mill. Initially there was an undershot waterwheel to the right outside of the picture.

- The 1771 mill as extended in 1785

- The foundations of the 1775 mill, which was destroyed by fire in 1890, with wheel chamber on the right

- Weavers' housing, North Street, Cromford

Restoration of hydropower capacity

[edit]Installation of a water wheel, accompanied by a modern 20 kW hydro-turbine to power the buildings, was approved in 2022.[15]

Buildings and structures

[edit]1771 mill

[edit]

1775 mill

[edit]

Waterworks

[edit]

Originally the sough drained into the brook back in the village, and both powered the original mill. The sough was separated and brought along a channel on the south side of Mill Road to the aqueduct. Both then supplied the second mill. In 1785 the mill was extended to its present length with a culvert beneath for the Bonsall Brook. The sough was separated from the brook and brought from the village along the south side of Mill Lane which it crossed by way of the aqueduct to a new overshot wheel. A complicated set of channels and sluices controlled the supply to the mill, or, on Sundays to the canal, with the surplus draining into the river.

Arkwright's use of the Bonsall Brook and Cromford Sough for his mills had been opposed by other local water users in a number of legal cases.[16] In 1772, however, a new sough, Meerbrook Sough, had been started nearby, some 30m lower than Cromford Sough. By 1813 the new sough was affecting the water volumes in Cromford Sough, leading Arkwright's son (also Richard Arkwright) and the other users to negotiate with the Meerbrook proprietors to place stop boards so as to keep Cromford water levels up. Further legal cases followed, but by 1836 the stop boards had decayed and the negotiated leases had expired, so Cromford Sough was again reduced in flow. Finally Arkwright sued for his water in a landmark legal suit,[17] but the case was lost, and soon after 1847 the Cromford Mills were obliged to cease cotton manufacturing, being turned over to other uses.[18]

- The sluice in the mill yard used to control the water supply

- Location of the breastshot wheel for the 1775 mill

- The culvert carrying the Bonsall Brook under the mill extension

- The 1771 mill showing the end of the aqueduct on the left and the hole in the wall where the wheel was located

- This shuttle in the village, known locally as the "Bear Pit", controlled the water from the sough.

- Cromford Pond built in 1785 as the mill pound

Housing

[edit]The mill manager had a house on site. Although the first workers were brought in from outside the area, workers' housing was later built in Cromford.

Cromford Canal and wharf

[edit]The opening of the Cromford Canal and the associated Cromford Wharf in 1793 linked Arkwright's Mill to the major Midland and northern cities, although use of the canal was to decline as traffic moved onto the railways.[19]

Machinery

[edit]Water frame

[edit]Initially the first stage of the process was hand carding, but in 1775 he took out a second patent for a water-powered carding machine and this led to increased output and the fame of his factory rapidly spread. He was soon building further mills on this site and others and eventually employed 1,000 workers at Cromford. Many other mills were built under licence, including mills in Lancashire, Scotland and Germany. Samuel Slater, an apprentice of Jedediah Strutt, took the secrets of Arkwright's machines to Pawtucket, Rhode Island,[20] USA,[21] where he founded a cotton industry. Arkwright's success led to his patents being challenged in court and his second patent was overturned as having no originality. Nonetheless, by the time of his death in 1792 he was the wealthiest untitled person in Britain.[22]

Cromford Mill has commissioned a replica water frame which was installed in April 2013. Considerable problems occurred in obtaining suitable roving, which had to be a low-twist 0.8 count cotton: there are no companies spinning cotton today in the United Kingdom. Roving was supplied eventually by Rieter in Switzerland, who had some experimental stock. Rieter are the world's largest manufacturer of textile manufacturing machines.[23]

See also

[edit]- Grade I listed buildings in Derbyshire

- Listed buildings in Cromford

- Kirk Mill

- Masson Mill

- New Lanark

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ a b Historic England. "Cromford Mill (Grade I) (1248010)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ^ Cooper 1983, p. 65.

- ^ Cooper 1983, p. 68.

- ^ Cooper 1983, p. 66.

- ^ Fisher, Stuart (12 January 2017). The Canals of Britain: The Comprehensive Guide. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 77. ISBN 9781472940025.

- ^ Willis, Alastair (20 March 2018). "Rare Cromford Dollars acquired by Derby Museums". Portable Antiquities Scheme. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ a b About Us

- ^ a b The Cromford Mills Creative Cluster and World Heritage Site Gateway Project, Derbyshire

- ^ Inside the £130m ‘conservation challenge of the century

- ^ Welcome to Cromford Mills Visit US

- ^ Site Map[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Cromford: SSSI citation" (PDF). Natural England. 22 August 1986. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ "Antiques Roadshow Venues for 2024: Cromford Mills, Derbyshire". BBC One. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Cromford Mills 2". Antiques Roadshow. Series 47. 20 October 2024. BBC One. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ Kataria, Sonia; Massey, Christina (1 August 2022). "Cromford Mill: Historic site secures cash for hydro power". BBC News. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ Vallerani, Francesco; Visentin, Francesco (2017). Waterways and the Cultural Landscape. Routledge. ISBN 9781138226043.

- ^ Gale, C.J.; Whatley, T.D. (1839). A Treatise on the Law of Easements. 1 Chancery Lane, London: S.Sweet. pp. 182–190.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Key Sites – Cromford Mill". Derwent Valley Mills. Derwent Valley Mills, ETE, County Hall, Matlock. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ^ "Cromford Mill and Sir Richard Arkwright". Derbyshire Guide website. Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ Heath, Neil (22 September 2011). "Samuel Slater: American hero or British traitor?". BBC News. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ "Old Slater Mill National Historic Landmark". Facebook (Facebook page). Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ "Richard Arkwright (1732–1792)". thornber.net. Archived from the original on 26 October 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ "The Cotton Rovings Saga". Sir Richard Arkwright's Cromford Mills. Arkwright Society. March 2013. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- Bibliography

- Cooper, Brian (1983), Transformation of a Valley: The Derbyshire Derwent (New, Scarthin 1997 Reprint ed.), London: Heinemann, ISBN 0-907758-17-7

External links

[edit]- Arkwright Society - Cromford Mill - with tour information

- Cromford village website

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch