Flag of Denmark

| |

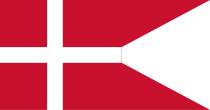

| Use | Civil flag and ensign |

|---|---|

| Proportion | 28:37 national[1][2] 56:107 royal |

| Adopted | 15 June 1219 (Dannebrog legend) 8 May 1625 (recognised as national flag)[3] |

| Design | A white Nordic cross with a red background |

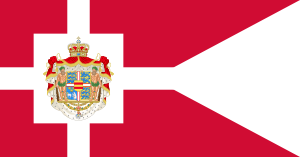

| Rigets flag—Flag of the Kingdom [of Denmark]; also known as Splitflaget | |

| |

| Use | State flag and ensign, war flag |

| Proportion | 56:107[2] |

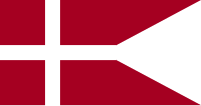

| Orlogsflag | |

| |

| Use | Naval ensign |

| Proportion | 7:17[2] |

| Adopted | 11 June 1748 |

The flag of Denmark (Danish: Dannebrog, pronounced [ˈtænəˌpʁoˀ])[4] is red with a white Nordic cross, which means that the cross extends to the edges of the flag and that the vertical part of the cross is shifted to the hoist side.

A banner with a white-on-red cross is attested as having been used by the kings of Denmark since the 14th century.[5] An origin legend with considerable impact on Danish national historiography connects the introduction of the flag to the Battle of Lindanise of 1219.[6]

The elongated Nordic cross, which represents Christianity, reflects its use as a maritime flag in the 18th century.[7] The flag became popular as a national flag in the early 16th century. Its private use was outlawed in 1834 but again permitted by a regulation of 1854. The flag holds the Guinness world record of being the oldest continuously used national flag, that is since 1625.[3]

Description

[edit]

A 1748 regulation, which is still in force, defines the flag as constructed of two squares of 4⁄4, with a white cross 1⁄7 the height of the flag and the two rectangular fields as 6⁄4.[1] Multiplying the proportions by three to get whole numbers gives the proportions in the construction sheet below (28 divided by 4 being 7 for the white cross).

Colour

[edit]No official definition of "Dannebrog rød" exists. The private company Dansk Standard, regulation number 359 (2005), defines the red colour of the flag as Pantone 186c.

Construction sheet

[edit]History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2019) |

1219 origin legend

[edit]

A tradition recorded in the 16th century traces the origin of the flag to the campaigns of Valdemar II of Denmark (r. 1202–1241). The oldest of them is in Christiern Pedersen's Danske Krønike, which is a sequel to Saxo Grammaticus's Gesta Danorum, which was written in 1520 to 1523. Here, the flag falls from the sky during one of Valdemar's military campaigns overseas. Pedersen also states that the very same flag was taken into exile by Eric of Pomerania in 1440.

The second source is the writing of the Franciscan friar Petrus Olai (Peder Olsen) of Roskilde (died c. 1570). This record describes a battle in 1208 near Fellin during the Estonia campaign of King Valdemar II. The Danes were all but defeated when a lamb-skin banner depicting a white cross fell from the sky and miraculously led to a Danish victory. In a third account, also by Petrus Olai,[dubious – discuss] in Danmarks Tolv Herligheder ("Twelve Splendours of Denmark"), in splendour number nine, the same story is retold almost verbatim, with a paragraph inserted correcting the year to 1219.[citation needed] Now, the flag is falling from the sky in the Battle of Lindanise, also known as the Battle of Valdemar (Danish: Volmerslaget), near Lindanise (Tallinn) in Estonia, of 15 June 1219.

It is this third account that has been the most influential, and some historians[who?] have treated it as the primary account taken from a (lost) source dating to the first half of the 15th century.

In Olai's account, the battle was going badly, and defeat seemed imminent. However the Danish bishop, Anders Sunesen, was on top of a hill overlooking the battle and prayed to God with his arms raised. The Danes moved closer to victory as prayed. When he raised his arms, the Danes surged forward, but when his arms grew tired, and he let them fall, the Estonians turned the Danes back. Attendants rushed forward to raise his arms once again, and the Danes again surged forward, but for a second time he grew so tired that he dropped his arms, and the Danes again lost the advantage and became closer to defeat. He needed two soldiers to keep his hands up (which might be a copycat of Exodus 17:11-12). When the Danes were about to lose, the Dannebrog miraculously fell from the sky. The King took it and showed it to the troops, their hearts were filled with courage, and the Danes won the battle.

The possible historical nucleus behind this origin legend was extensively discussed by Danish historians in the 19th to 20th centuries. One such example is Adolf Ditlev Jørgensen, who argued that Bishop Theoderich was the original instigator of the 1218 inquiry from Bishop Albert of Buxhoeveden to King Valdemar II which led to the Danish participation in the Baltic crusades. Jørgensen speculates that Bishop Theoderich might have carried the Knight Hospitaller's banner in the 1219 battle and that "the enemy thought this was the King's symbol and mistakenly stormed Bishop Theoderich tent. He claims that the origin of the legend of the falling flag comes from this confusion in the battle".[8]

The Danish church-historian L. P. Fabricius (1934)[9] ascribes the origin to the 1208 Battle of Fellin, not the Battle of Lindanise in 1219, based on the earliest source available about the story. Fabricius speculated that it might have been Archbishop Andreas Sunesøn's personal ecclesiastical banner or perhaps even the flag of Archbishop Absalon under whose initiative and supervision several smaller crusades had already been conducted in Estonia. The banner would then already be known in Estonia. Fabricius repeats Jørgensen's idea about the flag being planted in front of Bishop Theodorik's tent, which the enemy mistakenly attacked believing it to be the tent of the King.

A different theory is briefly discussed by Fabricius and elaborated more by Helge Bruhn (1949). Bruhn interprets the story in the context of the widespread tradition of the miraculous appearance of crosses in the sky in Christian legend, specifically comparing such an event attributed to a battle of 10 September 1217 near Alcazar in which it is said that a golden cross on white appeared in the sky and brought victory to the Christians.[10]

In Swedish national historiography of the 18th century, there is a tale paralleling the Danish legend, in which a golden cross appears in the blue sky during a Swedish battle in Finland in 1157.[11]

Middle Ages

[edit]

The white-on-red cross emblem originates in the age of the Crusades. In the 12th century, it was also used as war flag by the Holy Roman Empire.

In the Gelre Armorial, dated c. 1340–1370, such a banner is shown alongside the coat of arms of the king of Denmark.[12] This is the earliest known undisputed colour rendering of the Dannebrog. About the same time, Valdemar IV of Denmark displays a cross in his coat of arms on his Danælog seal (Rettertingsseglet, dated 1356). The image from the Armorial Gelre is nearly identical to an image found in a 15th-century coat of arms book now located in the National Archives of Sweden (Riksarkivet). The seal of Eric of Pomerania (1398) as king of the Kalmar Union displays the arms of Denmark's chief dexter, three lions. In this version, the lions hold a Dannebrog banner.

- Reichssturmfahne of the Holy Roman Empire

- Seal of Eric of Pomerania as king of the Kalmar union, 1398. A small Dannebrog banner is depicted as held by the three Danish lions in the top-left corner.

The reason that the kings of Denmark in the 14th century began displaying the cross banner in their coats of arms is unknown. Caspar Paludan-Müller (1873) suggested that it may reflect a banner sent by the pope to support the king during the Livonian Crusade.[13] Adolf Ditlev Jørgensen (1875) identifies the banner as that of the Knights Hospitaller, an order that had a presence in Denmark from the later 12th century.[8]

Several coins, seals and images exist, both foreign and domestic, from the 13th to the 15th centuries and even earlier and show similar heraldic designs similar, alongside the royal coat of arms (three blue lions on a golden shield.)

There is a record suggesting that the Danish Army had a "chief banner" (hoffuitbanner) in the early 16th century. Such a banner is mentioned in 1570 by Niels Hemmingsøn in the context of a 1520 battle between Danes and Swedes near Uppsala as nearly captured by the Swedes but saved by the heroic actions of the banner-carrier Mogens Gyldenstierne and Peder Skram. The legend attributing the miraculous origin of the flag to the campaigns of Valdemar II of Denmark (r. 1202-1241) was recorded by Christiern Pedersen and Petrus Olai in the 1520s.

Hans Svaning's History of King Hans from 1558 to 1559 and Johan Rantzau's History about the Last Dithmarschen War, from 1569, record the further fate of the Danish hoffuitbanner: According to the tradition, the original flag from the Battle of Lindanise was used in the small campaign of 1500, when King Hans tried to conquer Dithmarschen (in western Holstein in northern Germany). The flag was lost in a devastating defeat at the Battle of Hemmingstedt, on 17 February 1500. In 1559, King Frederik II recaptured it during his own Dithmarschen campaign.

In 1576, the son of Johan Rantzau, Henrik Rantzau, also writes about the war and the fate of the flag, noting that the flag was in a poor condition when returned. He records that the flag after its return to Denmark was placed in the cathedral in Slesvig. Slesvig historian Ulrik Petersen (1656–1735) confirms the presence of such a banner in the cathedral in the early 17th century and records that it had crumbled away by about 1660.

Contemporary records describing the battle of Hemmingstedt make no reference to the loss of the original Dannebrog, although the capitulation state that all Danish banners lost in 1500 was to be returned. In a letter dated 22 February 1500 to Oluf Stigsøn, King John describes the battle but does not mention the loss of an important flag. In fact, the entire letter gives the impression that the lost battle was of limited importance. In 1598, Neocorus wrote that the banner captured in 1500 was brought to the church in Wöhrden and hung there for the next 59 years until it was returned to the Danes as part of the peace settlement in 1559.

Modern period

[edit]

Used as a maritime flag since the 16th century, the Dannebrog was introduced as a regimental flag in the Danish army in 1785, and for the militia (landeværn) in 1801. From 1842, it was used as the flag of the entire army.[14]

During the first half of the 19th century, in parallel to the development of Romantic nationalism in other European countries, the military flag increasingly came to be seen as representing the nation itself. Poems of the period invoking the Dannebrog were written by B.S. Ingemann, N.F.S. Grundtvig, Oehlenschläger, Chr. Winther and H.C. Andersen.[14] By the 1830s, the military flag had become popular as an unofficial national flag, and its use by private citizens was outlawed in a circular enacted on 7 January 1834.

In the national enthusiasm sparked by the First Schleswig War from 1848 to 1850, the flag was still very widely displayed, and the prohibition of private use was repealed in a regulation of 7 July 1854 that for the first time allowed Danish citizens to display the Dannebrog (but not the swallow-tailed Splitflag variant.[15] Special permission to use the Splitflag was given to individual institutions and private companies, especially after 1870.[citation needed] In 1886, the war ministry introduced a regulation indicating that the flag should be flown from military buildings on thirteen specified days, including royal birthdays, the date of the signing of the Constitution of 5 June 1849 and days of remembrance for military battles. In 1913, the naval ministry issued its own list of flag days. On 10 April 1915, the hoisting of any other flag on Danish soil was prohibited.[16] The prohibition was lifted on 24 June 2023, after a Supreme Court ruling.[17] From 1939 to 2012, the yearbook Hvem-Hvad-Hvor included a list of flag days. As of 2019, flag days can be viewed at the "Ministry of Justice (Justitsministeriet)" as well as "The Denmark Society (Danmarks-Samfundet)".

Variants

[edit]Maritime flag and corresponding Kingdom flag

[edit]The size and shape of the civil ensign (Koffardiflaget) for merchant ships is given in the regulation of 11 June 1748, which says: "A red flag with a white cross with no split end. The white cross must be 1⁄7 of the flag's height. The two first fields must be square in form and the two outer fields must be 6⁄4 lengths of those". The proportions are thus: 3:1:3 vertically and 3:1:4.5 horizontally. This definition are the absolute proportions for the Danish national flag to this day, for both the civil version of the flag (Stutflaget), as well as the merchant flag (Handelsflaget). The civil flag and the merchant flag are identical in colour and design.

A regulation passed in 1758 required Danish ships sailing in the Mediterranean to carry the royal cypher in the center of the flag to distinguish them from Maltese ships because of its similarity of the flag of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta.

According to the regulation of 11 June 1748, the colour was simply red, which is common known today as "Dannebrog rød" ("Dannebrog red"). The only red fabric dye then available was made of madder root, which can be processed to produce a brilliant red dye and was used historically for British and Danish and soldiers' jackets. A regulation of 4 May 1927 once again stated that Danish merchant ships had to fly flags according to the regulation of 1748.

The first regulation regarding the Splitflag dates from 27 March 1630, in which King Christian IV ordered that Norwegian Defensionskibe (armed merchants ships) were allowed to use only the Splitflag if they were in Danish war service. In 1685, an order was distributed to a number of cities in Slesvig and stated that all ships had to carry the Danish flag, and in 1690, all merchant ships were forbidden to use the Splitflag except for ships sailing in the East Indies, the West Indies or along the coast of Africa. In 1741, it was confirmed that the regulation of 1690 was still very much in effect that merchant ships were not allowed to use the Splitflag. At the same time, the Danish East India Company was allowed to fly the Splitflag past the equator.

Some confusion must have existed regarding the Splitflag. In 1696 the Admiralty, presented the King with a proposal for a standard regulating both size and shape of the Splitflag. In the same year, a royal resolution defined the proportions of the Splitflag, which was called Kongeflaget (the King's flag), as follows: "The cross must be 1⁄7 of the flags height. The two first fields ,ist be square in form with the sides three times the cross width. The two outer fields are rectangular and 1+1⁄2 the length of the square fields. The tails are the length of the flag".

Those numbers are still the base for the Splitflag and the Orlogsflag though the numbers have been slightly altered. The term Orlogsflag dates from 1806 and denotes its use in the Danish Navy.

From about 1750 to the early 19th century, a number of ships and companies in which the government has interests received approval to use the Splitflag.

In the royal resolution of 25 October 1939 for the Danish Navy, it was stated that the Orlogsflag is a Splitflag with a deep red (dybrød) or madder red (kraprød) colour. As for the national flag, no shade was given, but it is now stated as 195U. Furthermore, the size and the shape were corrected in the new resolution: "The cross must be 1⁄7 of the flag's height. The two first fields must be square in form with the height of 3⁄7 of the flag's height. The two outer fields are rectangular and 5⁄4 the length of the square fields. The tails are 6⁄4 the length of the rectangular fields". Thus, if compared to the standard of 1696, both the rectangular fields and the tails have decreased in size.

The Splitflag and Orlogsflag have similar shapes but different sizes and shades of red. Legally, they are two different flags. The Splitflag is a Danish flag ending in a swallow-tail, it is Dannebrog red and is used on land. The Orlogsflag is an elongated Splitflag with a deeper red colour and is used only at sea.

The Orlogsflag with no markings may be used only by the Royal Danish Navy, but there are a few exceptions. A few institutions have been allowed to fly the clean Orlogsflag. The same flag with markings has been approved for a few dozen companies and institutions over the years.

Furthermore, the Orlogsflag is described as such only if it has no additional markings. Any swallow-tail flag, no matter the colour, is called a Splitflag provided it bears additional markings.

Royal standards

[edit]Monarch

[edit]The current version of the royal standard was introduced on 1 January 2025.[18] after King Frederik X adopted a new version of his personal coat of arms on 20 December 2024.[19] The royal standard is the flag of Denmark with a swallow-tail and charged with the monarch's coat of arms set in a white square. The centre square is 32 parts in a flag with the ratio 56:107.

Other members of the royal family

[edit]- Standard of Frederik, Crown Prince of Denmark (now King Frederik X) flying at Amalienborg

Other flags in the Kingdom of Denmark

[edit]Greenland and the Faroe Islands are autonomous territories[20] within the Kingdom of Denmark. They have their own official flags.

Some areas in Denmark have unofficial flags. While they have no legal recognition or regulation, they can be used freely.

The regional flags of Bornholm and Ærø are occasionally used by locals of those islands and in tourist-related businesses.

The proposal for a flag of Jutland has hardly found any actual use, maybe in part because of its peculiar design.[21]

The flag of Vendsyssel (Vendelbrog) is seen infrequently, but locals recognise it. According to an article in the newspaper Nordjyske, the flag had been used in the former insignia of Flight Eskadrille 723 of Aalborg Air Base, in the 1980s.

| Flag | Date introduced | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1633 | Unofficial flag of Ærø | Nearly square banner of horizontal yellow, green, and red stripes repeated three times. A historically incorrect version similar to the flag of Lithuania was used until 2015 |

| 1970s | Unofficial flag of Bornholm | Nordic Cross Flag in red and green. Also known in a version with a white fimbriation of the green cross in a style similar to design of the Norwegian flag |

| 1975 | Proposed flag of Jutland | Nordic Cross Flag in blue, green and red. Designed by Per Kramer in 1975[22] Rarely seen in use. |

| 1976 | Unofficial flag of Vendsyssel | Nordic Cross Flag in blue, orange and green[23] Designed by Mogens Bohøj.[24] |

See also

[edit]- Coat of Arms of Denmark

- Flag of Greenland

- Flag of the Faroe Islands

- List of Danish flags

- Nordic Cross flag

- Raven banner

- Flag of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta

- Flag of Savoy

- Danish Protest Pig, a breed of pig bred to look like the Danish flag.

- Flag of Sweden

- Flag of Norway

- Flag of Iceland

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Forordning om Coffardi-Skibes og Commis-Farernes samt de octrojerede Compagniers Skibes Flag og Giøs, samt Vimpeler og Fløie af 11. juli 1748" (in Danish). 7 November 1748. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Store Danske Encyklopædi – entry "Danmark -nationalflag"

- ^ a b "Oldest continuously used national flag". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 2023-11-10.

- ^ The word Dannebrog is recorded since the 19th century, and in the opinion of A. D. Jørgensen ("Om Danebroges Oprindelse", Historiske Afhandlinger 2, 1899), the word may be of medieval coinage. Old Danish brog continues Old Norse brók "piece of cloth; breeches, trousers"; the word is not now current in Danish outside of composition, and the Ordbog over det danske Sprog (1920 edition) listed it as "dated or poetic" (foræld. og poet.) for "trousers".

- ^ "Dannebrog" by Hans Christian Bjerg, p.12, ISBN 87-7739-906-4.

- ^ Andrew Evans (2008). Iceland. Bradt. ISBN 9781841622156. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

Legend states that a red cloth with the white cross simply fell from the sky in the middle of the 13th-century Battle of Valdemar, after which the Danes were victorious. As a badge of divine right, Denmark flew its cross in the other Scandinavian countries it ruled and as each nation gained independence, they incorporated the Christian symbol.

Inge Adriansen, Nationale symboler, Museum Tusculanum Press, 2003, p. 129: "Fra begyndelsen af 1400-tallet kan Dannebrog med sikkerhed dokumenteres som rigsflag, det vil sige statsmagtens og kongens flag" (English: "Dannebrog can with certainty be documented as flag of the realm, that is the flag of the authority of state and of the king, from the beginning of the 1400s") - ^ The medieval flags displaying crosses can be traced to the crusades and were later used as representing saints (as in the Saint George's Flag), the cross representing Christianity Jeroen Temperman (2010). State Religion Relationships and Human Rights Law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-9004181489. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

Many predominantly Christian states show a cross, symbolizing Christianity, on their national flag. Scandinavian crosses or Nordic crosses on the flags of the Nordic countries–Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden–also represent Christianity.

. The elongated cross design was subsequently adopted by other Nordic countries: Sweden, Norway, Finland, Iceland, and the Faroe Islands, as well as by the British archipelagos of Shetland and Orkney. - ^ a b Adolf Ditlev Jørgensen, Danebroges Oprindelse (1875)

- ^ L. P. Fabricius Sagnet om Dannebrog og de ældste Forbindelser med Estland (1934)

- ^ Helge Bruhn (1949). Dannebrog: og danske faner gennem tiderne. Jespersen og Pio. pp. 17–.

- ^ "Flag of Scania - ENG Part 1". www.skaneflaggan.nu. Retrieved 2024-04-15.

- ^ Volker Preuß. "National Flagge des Königreich Dänemark" (in German). Retrieved 2005-02-14.

- ^ Caspar Paludan-Müller Sagnet om den himmelfaldne Danebrogsfane (1873)

- ^ a b Sven Tito Achen, Heraldikkens femten glæder (1978), p. 108f.

- ^ Cirkulærer om ophævelse af forbuddet mod flagning i kanceli cirkulære af 7. januar 1834 (retsinformation.dk)

- ^ International Law Studies, Naval War College (U.S.), 1918, p. 83.

- ^ "Fra på lørdag er der fri bane til at flage med andre nationers flag i Danmark (From Saturday it's allowed to hoist other nations' flags in Denmark)". DR (in Danish). 2023-06-23. Retrieved 2023-11-11.

- ^ "Nye kongelige flag". www.kongehuset.dk (in Danish). 1 January 2025. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- ^ "Fastsættelse af nyt kongevåben". www.kongehuset.dk (in Danish). 1 January 2025. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- ^ * Benedikter, Thomas (2006-06-19). "The working autonomies in Europe". Society for Threatened Peoples. Archived from the original on 2008-03-09. Retrieved 2019-08-30.

Denmark has established very specific territorial autonomies with its two island territories

- Ackrén, Maria (November 2017). "Greenland". Autonomy Arrangements in the World. Archived from the original on 2019-08-30. Retrieved 2019-08-30.

Faroese and Greenlandic are seen as official regional languages in the self-governing territories belonging to Denmark.

- "Greenland". International Cooperation and Development. European Commission. 2013-06-03. Retrieved 2019-08-27.

Greenland [...] is an autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark

- "Facts about the Faroe Islands". Nordic cooperation. Archived from the original on 23 April 2018. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

The Faroe Islands [...] is one of three autonomous territories in the Nordic Region

- Ackrén, Maria (November 2017). "Greenland". Autonomy Arrangements in the World. Archived from the original on 2019-08-30. Retrieved 2019-08-30.

- ^ [1] Archived 2014-08-14 at the Wayback Machine harteg.dk Bornholms områdeflag afvist

- ^ "Flag, Danneborg, dannebrogsflag, dannebrogsvimpler og dannebrogsstander". Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved April 1, 2013. klauber-flag.dk

- ^ "Flag, Danneborg, dannebrogsflag, dannebrogsvimpler og dannebrogsstander". Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved April 1, 2013. klauber-flag.dk – Vendelbrog

- ^ "nordjyske.dk Det faldt ikke nedfra himlen ..." Archived from the original on 2016-12-14. Retrieved 2013-04-01.

General references

[edit]This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (June 2011) |

- Danmarks-Samfundet – several rules and customs about the use of Dannebrog

- Dannebrog, Helga Bruhn, Forlaget Jespersen og Pios, Copenhagen 1949

- Danebrog – Danmarks Palladium, E. D. Lund, Forlaget H. Hagerups, Copenhagen 1919

- Dannebrog – Vort Flag, Lieutenant Colonel Thaulow, Forlaget Codan, Copenhagen 1943

- DS 359:2005 'Flagdug', Dansk Standard, 2005

External links

[edit]- Denmark at Flags of the World

- Danish flag legendary birthplace in Estonia Archived 2012-08-23 at the Wayback Machine

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch