Di Renjie

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2023) |

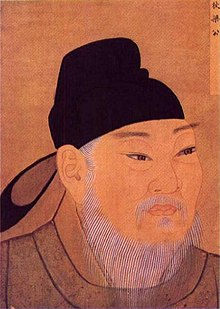

Duke Wenhui of Liang Di Renjie | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

狄仁傑 | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||

| Born | 630 Yangqu County, Taiyuan, Bing Province, Tang Empire | ||||||||||||||||

| Died | November 11, 700 (aged 69–70) Luoyang, Wu Zhou Empire | ||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | White Horse Temple, Luoyang | ||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | Chinese | ||||||||||||||||

| Children |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Parent |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Occupation | Politician | ||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 狄仁傑 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 狄仁杰 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Di Renjie (630 – November 11, 700),[1] courtesy name Huaiying (懷英), formally Duke Wenhui of Liang (梁文惠公), was a Chinese politician of the Tang and Wu Zhou dynasties, twice serving as chancellor during the reign of Wu Zetian. He was one of the most celebrated officials of Wu Zetian's reign. Di Renjie is depicted in the Wu Shuang Pu (無雙譜, Table of Peerless Heroes) by Jin Guliang.

Background

[edit]Di Renjie was born in Yangqu County, Bing Province, in 630, during the reign of Emperor Taizong. His family, from Taiyuan, was one that had produced many officials. His grandfather, Di Xiaoxu (狄孝緒), served as Shangshu Zuo Cheng (尚書左丞), a secretary general of the executive bureau of government (尚書省, Shangshu Sheng), and his father, Di Zhixun (狄知遜), served as the prefect of Kui Prefecture (夔州, modern eastern Chongqing).

Di Renjie was known for being studious in his youth, and after passing the imperial examination served as a secretary at the prefectural government of Bian Prefecture (汴州, roughly modern Kaifeng, Henan). While serving there, he was falsely accused of improprieties by colleagues, and when the minister of public works, Yan Liben, was touring the Henan Circuit (河南道, the region immediately south of the Yellow River), which Bian Prefecture belonged to, he was asked to judge the case. After seeing Di, he was impressed by him, and commented, "Confucius had said, 'You can tell a man's kindness by his failure.' You are a pearl from the coast and a lost treasure of the southeast." He recommended Di to become a bailiff for the commandant at Bing Prefecture (并州, roughly modern Taiyuan, Shanxi).

While at Bing Prefecture, he was said to be caring of others. On one occasion, his colleague Zheng Chongzhi (鄭崇質) was ordered to go on an official trip to a place far away. Di, noting that Zheng's mother was old and ill, went to the secretary general Lin Renji (藺仁基) and offered to go in Zheng's stead. It was said that Lin was so touched by the concern that Di showed Zheng as a colleague that he relayed the episode to the military advisor to the prefect, Li Xiaolian (李孝廉), with whom Lin had a running dispute, and offered peaceful relations to Li.

By 676, during the reign of Emperor Taizong's son Emperor Gaozong, Di was serving as the secretary general at the supreme court (大理丞), and it was said that he was an efficient and fair judge, judging some 17,000 cases within a year without anyone complaining about the results. In 676, there was an event in which the general Quan Shancai (權善才) and the military officer Fan Huaiyi (范懷義) accidentally cut cypresses on Emperor Taizong's tomb—an offense punishable by removal from office, but Emperor Gaozong ordered that the two be executed. Di pointed out that, by law, the two should not be executed. This initially offended Emperor Gaozong, who ordered Di to leave his presence. Di continued to object, and eventually, Emperor Gaozong relented and exiled them. Several days later, he appointed Di to the imperial censorate.

Around 679, the minister of agriculture Wei Hongji (韋弘機) built three magnificent palaces around the eastern capital Luoyang—Suyu Palace (宿羽宮), Gaoshan Palace (高山宮), and Shangyang Palace (上陽宮). Di submitted an accusation against Wei, arguing that he was leading Emperor Gaozong into being wasteful, and Wei was removed from his office. Meanwhile, around the same time, the official Wang Benli was said to be favored by Emperor Gaozong and, on account of that favor, was committing many illegal deeds and intimidating other officials. Di accused Wang of crimes; initially, Emperor Gaozong was set to pardon him. At Di's insistence—pointing out that the empire did not lack people with Wang's talent—Emperor Gaozong relented and allowed Wang to be punished.

During Emperor Ruizong's first reign

[edit]

As of 686, during the reign of Emperor Gaozong's son Emperor Ruizong, Di Renjie was serving as the prefect of Ning Prefecture (寧州, roughly modern Qingyang, Gansu). At that time, the censor Guo Han (郭翰) was commissioned to tour the prefectures in the area, and wherever he went, he found faults with the prefects and corrected them, but when he arrived at Ning Prefecture, it was said that the people had no complaints about Di and praised him greatly. Guo recommended Di to Emperor Ruizong's mother and regent Empress Dowager Wu (later known as Wu Zetian), and Di was recalled to Luoyang to serve as deputy minister of public works (冬官侍郎, Dongguan Shilang).

In 688, Di was touring the Jiangnan Circuit (江南道, the region south of the Yangtze River). He believed that the region had too many temples dedicated to unusual deities, and at his request, some 1,700 temples were destroyed; only four kinds of temples were allowed to remain—those dedicated to Yu the Great, Wu Taibo (吳太伯, the legendary founder of the Spring and Autumn period kingdom Wu), Wu Jizha (吳季札, a well-regarded Wu prince and son of King Shoumeng of Wu), and Wu Zixu.

Later in 688, in the aftermath of a failed rebellion by Emperor Gaozong's brother Li Zhen the Prince of Yue, then the prefect of Yu Prefecture (豫州, roughly modern Zhumadian, Henan), against Empress Dowager Wu, she made Di, who was at that time Wenchang Zuo Cheng (文昌左丞), a secretary general at the executive bureau (which by that point had been renamed Wenchang Tai (文昌臺)), the prefect of Yu Prefecture to succeed Li Zhen. At that time, some 600 to 700 households were accused of being complicit in Li Zhen's rebellion and were forced to serve as servants. At Di's request, they were relieved from those obligations, but were exiled to Feng Prefecture (豐州, roughly modern Bayan Nur, Inner Mongolia).

Meanwhile, the general that Empress Dowager Wu sent to suppress Li Zhen's rebellion, the chancellor Zhang Guangfu, was still in Yu Prefecture, and his officers and soldiers were demanding various supplies from the Yu prefectural government, requests that Di mostly turned down. This led to an argument with Zhang, and Zhang accused him of showing contempt. In turn, Di angrily stated that Zhang was killing alleged coconspirators of Li Zhen excessively and that if he had the authority to do so, he would have beheaded Zhang even if it meant his own death. Zhang was greatly offended and, upon returning to Luoyang, accused Di of contempt, and Empress Dowager Wu demoted Di to be the prefect of Fu Prefecture (復州, in modern Hanzhong, Shaanxi). (This was considered a demotion as, while Di remained a prefect, Fu Prefecture was smaller and less important than Yu Prefecture.)

During Wu Zetian's reign

[edit]

Inscription on tombstone: Tomb of Lord Di Renjie, famous chancellor of the Great Tang dynasty

In 690, Empress Dowager Wu took the throne from Emperor Ruizong, establishing the Zhou dynasty as its "emperor" and interrupting the Tang dynasty. As of 691, Di was serving as the military advisor to the prefect of the capital prefecture of Luo Prefecture (洛州, i.e., Luoyang), when Wu Zetian promoted him to be the deputy minister of finance (地官侍郎, Diguan Shilang) and gave him the designation Tong Fengge Luantai Pingzhangshi (同鳳閣鸞臺平章事), making him a 'de facto chancellor.'

She commented to him, "You did a good job in Ru'nan [(汝南, i.e., Yu Prefecture)]. Do you want to know who spoke against you?" (Presumably, she was referring to Zhang Guangfu who, ironically, was executed by her in 689 on accusations that he had considered rebelling against her.) Di responded:

If Your Imperial Majesty believed that I had faults, I am willing to correct them. If Your Imperial Majesty believed that I am without fault, that is my good fortune. I do not wish to know who spoke against me.

Wu Zetian was impressed by the response and praised him. Later that year, when the imperial university's student Wang Xunzhi (王循之) submitted a petition to Wu Zetian asking her to permit him to go on vacation, she was poised to issue an edict to approve of the request, when Di opposed the edict—not on the merits, but on the basis that university students' vacations were such minor events that she should not bother herself with them, but rather should order that such petitions be directed to the university secretaries. She agreed.

In 692, Wu Zetian's secret police official, Lai Junchen, falsely accused Di, along with other chancellors Ren Zhigu, and Pei Xingben, along with other officials Cui Xuanli (崔宣禮), Lu Xian (盧獻), Wei Yuanzhong, and Li Sizhen (李嗣真), of treason. Lai tried to induce them to confess by citing an imperial edict that stated that those who confessed would be spared their lives, and Di confessed and was not tortured—but when Lai's subordinate Wang Deshou (王德壽) tried to induce him to implicate another chancellor, Yang Zhirou, he refused. Di then wrote a petition on his blanket and hid it inside cotton clothes, and then had his family members take the clothes home to be changed into summer clothes. Wu Zetian thereafter became suspicious and inquired with Lai, who responded by forging, in the names of Di and the other officials, submissions thanking Wu Zetian for preparing to execute them.

However, the young son of another chancellor who had been executed, Le Sihui, who was seized to be a servant at the ministry of agriculture, made a petition to Wu Zetian and told her that Lai was so skillful at manufacturing charges that even the most honest and faithful individuals would be forced into confessions by Lai. Wu Zetian thereafter summoned the seven accused officials and personally interrogated them, and after they disavowed the forged confessions, released but exiled them—in Di's case, to be the magistrate of Pengze County (彭澤, in modern Jiujiang, Jiangxi).

In 696, during the middle of an attack by the Khitan khan Sun Wanrong against Zhou prefectures north of the Yellow River, Wu Zetian promoted Di to be the prefect of Wei Prefecture (魏州, roughly modern Handan, Hebei). It was said that Di's predecessor Dugu Sizhuang (獨孤思莊), in fear of a Khitan attack, had ordered the people of the prefecture to all move within the prefectural capital's walls, drawing much fear and resentment from the people. When Di arrived, he, judging the Khitan forces to be still far away, ordered that the people be allowed to return to their homes and farms, gaining much gratitude from the people. After Sun's forces collapsed in 697 after a surprise attack by the Eastern Tujue khan Ashina Mochuo against his home base, Wu Zetian had Di, the chancellor Lou Shide, and Wu Yizong (武懿宗), the Prince of Henan (a grandson of her uncle Wu Shiyi (武士逸)), to tour the region north of the Yellow River to try to pacify the people.

Later in 697, Di was serving as the commandant at You Prefecture (幽州, roughly modern Beijing), when, at Lou's recommendation, Wu Zetian recalled him to Luoyang to serve as Luantai Shilang (鸞臺侍郎), the deputy head of the examination bureau of government (鸞臺, Luantai), and again gave him the chancellor designation of Tong Fengge Luantai Pingzhangshi. He submitted a petition advocating that descendants of Western Tujue and Goguryeo rulers be found and be given their ancient lands, to help defend against Eastern Tujue and Tufan attacks—a petition that was not accepted but was said to be well-regarded by other officials.

At that time, Wu Zetian's son Li Dan (the former Emperor Ruizong) was crown prince, but Wu Zetian's nephews Wu Chengsi, the Prince of Wei, and Wu Sansi, the Prince of Liang, both had designs on the position, and repeatedly had their associates reason with Wu Zetian that there had never been an emperor who made someone of a different family name his heir. Di, on the other hand, repeatedly argued to her that it is more proper for her to make her son her heir, and that Li Dan's brother, Li Zhe, the Prince of Luling, himself a former emperor that Wu Zetian removed in 684, be recalled to the capital, a suggestion echoed by fellow chancellors Wang Fangqing and Wang Jishan, and Wu Zetian began to agree. On one occasion, Wu Zetian asked him, "Last night I dreamed of a large parrot that had two broken wings. What do you think it means?" Di responded:

Wu [(the second character of "parrot," yingwu (鸚鵡)) is a homophone of Your Imperial Majesty's family name. The two wings are your two sons. If you give important positions to your two sons, the two wings will surely recover.

It was said that thereafter, Wu Zetian stopped considering Wu Chengsi or Wu Sansi as heir. Meanwhile, another close advisor of Wu Zetian's, Ji Xu, also persuaded Wu Zetian's lovers, Zhang Yizhi and Zhang Changzong, on the merits of the proposal—pointing out that as things stood, after Wu Zetian's death, they would be hated and would suffer terrible fates. Wu Zetian finally agreed, and in spring 698 recalled Li Zhe to the capital. Li Dan subsequently offered to yield the crown prince position to Li Zhe, and Wu Zetian agreed and made Li Zhe crown prince, changing his name to Li Xian, and then Wu Xian. She soon made Di Nayan (納言), the head of the examination bureau and a post considered one for a chancellor.

Also in 698, Ashina Mochuo turned against Zhou and attacked Zhou's northern prefectures. Wu Zetian made Li Xian the nominal commanding general of the army against Eastern Tujue, but made Di the deputy commanding general and actually in charge of the army. Before Di's army could arrive, however, Ashina Mochuo completed his pillaging of the northern prefectures and withdrew; Di's army never engaged him. Wu Zetian subsequently commissioned Di to tour the prefectures to pacify the people, and he was said to have done so well, helping refugees to return to their home, transporting food supplies to places needing them, repairing the roads, and helping the poor. Fearful that other officials would trouble the people with demands for luxury items, he made a good example of eating unrefined foods and prohibiting harassment of the citizens. Meanwhile, though, he was said to have looked down on Lou, not realizing that Lou had been the one that had recommended that he be made chancellor, until Wu Zetian revealed to him that fact, causing him to be embarrassed.

On 12 January 700,[2] Wu Zetian made Di Neishi (內史), the head of the legislative bureau (鳳閣, Fengge) and a post also considered one for a chancellor. By this point, she was said to have respected him so greatly that she often just referred to him as Guolao (國老, "the State Elder") without referring to him by name. It was said that, on account of his old age, he often offered to retire, and she repeatedly declined. Further, she stopped him from kneeling and bowing to her, stating, "When I see you kneeling, I feel the pain." She also ordered that he not be required to rotate with other chancellors for night duty, warning the other chancellors not to bother Di unless there was something important. Di died in November that year, and it was said that she wept bitterly, stating, "The Southern Palace [(i.e., the imperial administration)] is now empty."

Prior to his death, Di had recommended many capable officials, including Zhang Jianzhi, Yao Yuanchong, Huan Yanfan, and Jing Hui. As these officials were later instrumental in overthrowing Wu Zetian in 705 and returning Li Xian to the throne (as Emperor Zhongzong), Di was often credited as having restored Tang by proxy.

Di Renjie's tomb is located at the east end of the White Horse Temple in Luoyang, near the Qiyun Pagoda, on the tombstone engraved the inscription "The tomb of Lord Di Renjie, famous chancellor of the Great Tang dynasty".

In fiction

[edit]Di Renjie appears as the main character in a number of gong'an crime novels and films. The first of these was a 64-chapter novel titled Wu Zetian sida qi’an 武则天四大奇案 (Wu Zetian's Four Great Cases), also known as Di gong’an 狄公案 (The Cases Solved by Judge Di), written by a pseudonymous author in 1890. [3]

During his office in China, Robert van Gulik translated the first 30 chapters of the Chinese novel Di gong’an into English, and published it on his own in Tokyo in 1949 under the title Dee Goong An: Three Murder Cases Solved by Judge Dee.[3]

He later wrote a series of detective novels featuring Judge Dee (“Dee” is the English adaptation of the Chinese pinyin “Di”) as the main protagonist. These, in turn, were the basis of a 1969 TV series in the UK starring Michael Goodliffe.

Khigh Dhiegh appeared as the Judge Dee version of the character in the 1974 ABC TV movie Judge Dee and the Monastery Murders, based on Robert Van Gulik's novel The Haunted Monastery. It was directed by Jeremy Paul Kagan and the teleplay was written by Nicholas Meyer.

Frédéric Lenormand published 19 new novels using Judge Dee as detective from 2004 to present (éditions Fayard, Paris).

Van Gulik's series of detective novels was not translated into Chinese until the 1980s, when Professor Zhao Yiheng 赵毅衡, during his studies at the Institute of Foreign Languages of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (Zhongguo shehui kexueyuan waiwen yanjiusuo 中国社会科学院外文研究所), “re-discovered” it in the National Library of Beijing. Professor Zhao was completely fascinated by van Gulik's series, and thought that Chinese people must read such lovely novels that re-invented Chinese history and Chinese society. In 1981, he wrote an article entitled The Western Di gong’an that win universal acclaim (Kuaizhi renkou de xiyang Digong’an 脍炙人口的西洋狄公案) to introduce to the Chinese reader van Gulik's series, and published it in Zhonghua dushubao (中华读书报) and later, on Renmin Ribao (人民日报). These articles immediately aroused great interest in China. Magazines, newspapers, and publishing houses wrote to Zhao Yiheng to pray for him to translate van Gulik's stories, but Zhao was too busy and asked his friend Chen Laiyuan (陈来元). After that, Cheng Laiyuan, his wife, and two of his friends worked hard from the spring of 1981 until the summer of 1986, and finally all van Gulik's stories were published in China under the title Di Renjie solves cases at the court of the Great Tang (Da Tang Di gong’an 大唐狄公案). In 1986, Chen Laiyuan and his colleagues also collaborated on the adaptation for Chinese television of a serial drama titled The Legend of the Detective Di Renjie (Di Renjie duan’an chuanqi 狄仁杰断案传奇), the first Chinese television drama based on Judge Dee. It was a twenty-five-episode detective drama adapted from Van Gulik's Judge Dee mysteries. Each of van Gulik's stories were adapted into one, two, or three episodes, although some simplifications were made due to the small screen requirements.

In 1996, another television drama titled The Legend Di Renjie and Wu Zetian (Di Renjie yu Wu Zetian Chuanqi 狄仁杰与武则天传奇, 1996) appeared in Chinese television. Here, Di Renjie's representation resonates strongly with the age-old literary tradition of “pure officials” that had enjoyed enduring popularity in the past. Unlike the drama of 1986, this time, great attention was paid to historical details and to the construction of the characters based on historical figures. Here, Di Renjie is no longer a Western detective in the shoes of a Chinese official, he no longer lives in the “eternal China” described by van Gulik, but he reactivates the cultural icon of “pure official” who fights corruption and crimes. (see: L. Benedetti, Further definition of Di Renjie's identity(ies) in Chinese history, literature, and media, «Frontiers of History in China», 2017, 12(4), pp. 599–620.)

In 2004, CCTV-8 aired a television series based on detective stories related to Di Renjie, under the title Amazing Detective Di Renjie (神探狄仁杰), starring Liang Guanhua as the titular protagonist. It was followed by three sequels: Amazing Detective Di Renjie 2 (2006), Amazing Detective Di Renjie 3 (2008), and Mad Detective Di Renjie (2010). Some characters in the television series are fictionalised versions of historical figures, including Wu Zetian and Di Renjie himself. The plot of each season is further divided into two or three parts, each covering one case. The story usually follows a pattern of a seemingly small case gradually leading to Di Renjie uncovering a sinister plot that threatens the Chinese empire.

Kent Cheng portrayed Di Renjie in the 2009 Hong Kong television series The Greatness of a Hero, produced by TVB.

Andy Lau played Di Renjie in the 2010 film Detective Dee and the Mystery of the Phantom Flame directed by Tsui Hark. Mark Chao took over the role in Young Detective Dee: Rise of the Sea Dragon (2013) and Detective Dee: The Four Heavenly Kings (2018), both also directed by Tsui Hark. The two films are set as a prequel to the events in The Mystery of the Phantom Flame.

Bosco Wong portrayed a young Di Renjie in the 2014 Chinese television series Young Sherlock.

2024, Youku released a series called Judge Dee's Mystery, which was also sold to Netflix. Zhou Yiwei as Judge Di.

In 2012, Bigben Interactive released a video game based on Di Renjie named Judge Dee: The City God Case. Initially released on PC, the casual hidden-object game later made it on to other platforms, including Android and iOS.

Nupixo Games released a new point-and-click adventure game featuring an original story which involves Empress Wu Zetian. Titled Detective Di: The Silk Rose Murders, it was released in May 2019 for PC/Mac.

References

[edit]- ^ (久视元年...九月辛丑,狄仁杰薨。) Xin Tang Shu, vol.04. Volume 207 of Zizhi Tongjian also recorded the same death date, while Wu Zetian's biography in Old Book of Tang only recorded that he died in the 9th month of that year (recorded as the 3rd year of the Sheng'li era), which corresponds to 17 Oct to 14 Nov 700 in the Julian calendar. His biography in New Book of Tang indicate that he was 71 (by East Asian reckoning) when he died. (圣历三年卒,年七十一。) Xin Tang Shu, vol.115

- ^ ([久视元年]腊月,...丁酉,以狄仁杰为内史。) Zizhi Tongjian, vol.206

- ^ a b L. Benedetti: Further definition of Di Renjie’s identity(ies) in Chinese history, literature, and media.

- Lavinia Benedetti, Further definition of Di Renjie's identity(ies) in Chinese history, literature and media, Frontiers of History in China, 2017, 12(4), pp. 599–620. Front.Hist. China 2017. DOI 10.3868/s020-006-017-0028-4.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch