Duck decoy (structure)

A duck decoy is a device to capture wild ducks or other species of waterfowl. Decoys had an advantage over hunting ducks with shotguns as the duck meat did not contain lead shot. Consequently, a higher price could be charged for it.

Decoys are still used for hunting ducks, but they are now also used for ornithological research, in which the birds are released after capture.

Etymology

[edit]The word decoy is derived from the Dutch word eendenkooi, which means "duck-cage";[2] Chambers Dictionary suggests Dutch de kooi = "the cage".

Description

[edit]

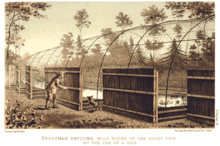

As finally developed, the decoy consisted of a pool of water, leading from which are from one to eight curved, tapered, water-filled ditches. Over each ditch is a series of hoops, initially made from wood, later from iron, which diminish in size as the ditch tapers. The hoops are covered in netting. The combination of ditch and net-covered hoop is known as a pipe. On the outside curve of the pipe, for two-thirds of its length, there are overlapping screens.[3]

Operation

[edit]

Wild ducks fly in to settle on the central pool; the decoy operator might maintain a resident population of tame ducks to encourage them to do this.[5] When a sufficient number have gathered, they are encouraged to swim down one of the pipes leading from the pool, where they are trapped. If the decoy has several pipes, then wind direction determines which one is used – it is important for the wind to be blowing approximately up the pipe so the decoyman remains downwind of the ducks.[6]

Ducks are encouraged to swim up the pipe using a dog, by feeding them, or a combination of both.

- Use of dogs

- Ducks are naturally curious and when they see a predator, such as a fox, they will keep it at a distance, but tend to follow it. The decoyman uses a dog, preferably a breed similar in appearance to a fox, to lure the ducks along the pipes. For this purpose in the sixteenth century in the Netherlands the kooikerhondje breed was developed. The dog appears between a gap in the screens and the ducks approach. It then appears at the next gap further along the pipe, and so on until the ducks are trapped at the end of the pipe. For a dog to be suitable for this task, it must not bark, and must be completely obedient to the decoyman. The decoy man quietly directs the dog using hand gestures while watching the progress of the ducks using peep-holes in the screens.[7]

- Feeding

- The decoyman walks behind the screens, throwing grain or other food over them while keeping out of sight. The ducks follow, eating the food, and are caught at the end of the pipe. This task requires some experience and judgment as too little food will not encourage the ducks to swim further down the pipe. While if too much is thrown to them, they will remain where they are to consume what's there.[8] The decoyman might also have trained the tame ducks to associate a gentle whistling noise with feeding time. By blowing a whistle, the tame ducks will be encouraged to swim up the pipe, and the wild ducks will be more likely to follow them.[9]

Today

[edit]England

[edit]

In the mid-1880s there were 41 decoys still in operation in England, and 145 which were no longer in use.[10] Today there are only a few remaining duck decoys in England. These include Hale Duck Decoy in Cheshire, administered by Halton Borough Council,[11] Boarstall Duck Decoy near Aylesbury in Buckinghamshire, owned and administered by the National Trust,[12] and a decoy in Abbotsbury Swannery, Dorset.[13]

Some are used to trap ducks for non-harmful study, such as ringing them.[14][15]

Evidence of former duck decoys can be found. At Swanpool near Lincoln, cropmarks revealed in aerial photographs show the outlines of a decoy.[16] In Somerset, west of Nyland Hill there is a well-preserved pond with six pipes,[17] and in Westbury there is also a decoy with possibly six pipes (though only some of pipes are still visible).[18]

Wales

[edit]Duck decoys were widespread in Wales, with that at Orielton, Pembrokeshire being especially well-known.[19]

Scotland

[edit]Duck decoys were rare in Scotland, but one example is known from Ackergill Tower, Caithness.[20]

Ireland

[edit]Duck decoys were brought to Ireland with Dutch immigration in the 17th century.[21] In his diaries, Sir William Brereton, 1st Baronet describes a "coy" in County Wexford as early as 1635.[21]

Netherlands

[edit]There are about 111 decoys still in operation in the Netherlands with one of the oldest dating from the 13th century.[22][23] The number of ducks still caught for consumption is small. Larger numbers of ducks are hunted by shooting. The decoys are mostly used for study purposes including ringing, but also for studying the avian flu.[24]

Denmark and Germany

[edit]On the North Frisian Islands, decoys originally served as a pastime for sea captains and ships' officers during wintertime. Later the ponds were also used to trap great numbers of wild ducks for commercial purposes. In one decoy on Föhr island, more than 3,000,000 ducks have been caught since its installation in 1735, and from 1885 to 1931 a factory for canned duck meat was active in Wyk auf Föhr. The preserved meat was exported worldwide. Today there are six inactive decoys on Föhr.[25] Another decoy is located near Norddorf on Amrum island.[26] The decoy on Pellworm island was active until 1946. Today it is a public park and has been converted into an orchard.[27]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

- ^ Payne-Gallwey 1886, p. 59

- ^ Payne-Gallwey 1886, p. 3.

- ^ Payne-Gallwey 1886, pp. 18–20.

- ^ Payne-Gallwey 1886, p. 26

- ^ Payne-Gallwey 1886, p. 40

- ^ Payne-Gallwey 1886, p. 51

- ^ Payne-Gallwey 1886, pp. 23–26.

- ^ Payne-Gallwey 1886, pp. 27–29.

- ^ Whitaker 1918, p. 6

- ^ Payne-Gallwey 1886, pp. 60–187.

- ^ Hale Duck Decoy, Halton Borough Council, archived from the original on 2008-04-03, retrieved 2008-10-04

- ^ Boarstall Duck Decoy, National Trust, archived from the original on 2009-04-05, retrieved 2008-10-04

- ^ Chesil & Fleet A to Z, Chickerell BioAcoustics, archived from the original on 2014-09-13, retrieved 2008-10-06

- ^ Cook, W. A. (1963). "Birds at Borough Fen Decoy in 1960 – 1962". The Wildfowl Trust Fourteenth Annual Report (Report). pp. 150–152.

- ^ Kear, Janet (June 1993). "Duck decoys, with particular reference to the history of bird ringing". Archives of Natural History. 20 (2): 229–240. doi:10.3366/anh.1993.20.2.229.

- ^ Duck Decoy at Swanpool, English Heritage, retrieved 2008-10-04

- ^ Duck decoy, W of Nyland Hill, Nyland, Somerset County Council, retrieved 2008-10-04

- ^ Duck decoy, E of Barrow Wood Lane, Westbury, Somerset County Council, retrieved 2008-10-04

- ^ "Orielton Duck Decoy: the story of its decline – Field Studies Council".

- ^ Sellers, Robin M. (December 22, 2020). "An unusual and previously overlooked duck decoy in the north of Scotland". Wildfowl. 70 (70): 267–274 – via wildfowl.wwt.org.uk.

- ^ a b Costello, Vandra (2002). "Dutch Influences in Seventeenth-Century Ireland: The Duck Decoy". Garden History. 30 (2): 177–190. doi:10.2307/1587251.

- ^ "Eendenkooien in Nederland" [Decoys in the Netherlands] (in Dutch). De Kooikersvereniging. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ Bestuur Oud Sassenheim (2007). De geschiedenis van Sassenheim in Vogelvlucht (PDF) (in Dutch). Stichting Oud Sassenheim. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2012.

- ^ Wetenschappelijk onderzoek [Scientific studies]. Lesbrief Sassenheimse Geschiedenis (in Dutch). De Kooikersvereniging. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ Faltings, Jan I. (2011), Föhrer Grönlandfahrt im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert (in German), Amrum: Verlag Jens Quedens, pp. 36–37, ISBN 978-3-924422-95-0

- ^ "Norddorf: Regionale Ziele". Marco Polo (in German). MairDumont. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ "Die Vogelkoje - ein Ort der Stille" [The duck decoy – a place of tranquility]. Pellworm.de (in German). Pellworm municipality. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

Bibliography

- Payne-Gallwey, Ralph (1886). The book of duck decoys, their construction, management, and history. London, J. Van Voorst.

- Whitaker, J. (1918). British duck decoys of today, 1918. London : Burlington Pub. Co.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch