Dunkleosteus

| Dunkleosteus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Partially reconstructed D. terrelli skull and trunk armor (specimen CMNH 5768), Cleveland Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | †Placodermi |

| Order: | †Arthrodira |

| Suborder: | †Brachythoraci |

| Family: | †Dunkleosteidae |

| Genus: | †Dunkleosteus Lehman, 1956 |

| Type species | |

| †Dinichthys terrelli Newberry, 1873 | |

| Species | |

| List

| |

Dunkleosteus is an extinct genus of large arthrodire ("jointed-neck") fish that existed during the Late Devonian period, about 382–358 million years ago. It was a pelagic fish inhabiting open waters, and one of the first vertebrate apex predators of any ecosystem.[1]

Dunkleosteus consists of ten species, some of which are among the largest placoderms ("plate-skinned") to have ever lived: D. terrelli, D. belgicus, D. denisoni, D. marsaisi, D. magnificus, D. missouriensis, D. newberryi, D. amblyodoratus, D. raveri, and D. tuderensis. However, the validity of several of these species is unclear. The largest and best known species is D. terrelli. Since body shape is not known, various methods of estimation put the living total length of the largest known specimen of D. terrelli between 4.1 to 10 m (13 to 33 ft) long and weigh around 1–4 t (1.1–4.4 short tons).[2] Lengths of 5 metres (16 ft) or more are poorly supported, with the most recent and extensive studies on the body shape and size of D. terrelli producing estimated lengths of approximately 3.4 metres (11 ft) for typical adults and 4.1 metres (13 ft) for exceptionally large individuals of this species.[2][3][4]

Dunkleosteus could quickly open and close its jaw, creating suction like modern-day suction feeders, and had a bite force that is considered the highest of any living or fossil fish, and among the highest of any animal. Fossils of Dunkleosteus have been found in the United States, Canada, Poland, Belgium, and Morocco.

Discovery

[edit]Dunkleosteus fossils were first discovered in 1867 by Jay Terrell, a hotel owner and amateur paleontologist who collected fossils in the cliffs along Lake Erie near his home of Sheffield Lake, Ohio (due west of Cleveland), United States. Terrell donated his fossils to John Strong Newberry and the Ohio Geological Survey, who in 1873 described all the material as belonging to a single new genus and species: Dinichthys herzeri. However, with later fossil discoveries, by 1875 it became apparent multiple large fish species were present in the Ohio Shale. Dinichthys herzeri came from the lowermost layer, the Huron Shale, whereas most of the fossils were coming from the younger Cleveland Shale and represented a distinct species.[5] Newberry named this more common species "Dinichthys" terrelli, after Terrell.[6] Most of Terrell's original collection does not survive, having been destroyed by a fire in Elyria, Ohio, in 1873.[5][7]

The largest collection of Dunkleosteus fossils in the world is housed at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History,[8] with smaller collections (in descending order of size) held at the American Museum of Natural History,[9] Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History,[10] Yale Peabody Museum,[11] the Natural History Museum in London, and the Cincinnati Museum Center. Specimens of Dunkleosteus are on display in many museums throughout the world (see table below), most of which are casts of the same specimen: CMNH 5768, the largest well-preserved individual of D. terrelli.[2][12] The original CMNH 5768 is on display in the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

Taxonomy

[edit]Dunkleosteus was named by Jean-Pierre Lehman in 1956 to honour David Dunkle (1911–1984), former curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. The genus name Dunkleosteus combines David Dunkle's surname with the Greek word ὀστέον (ostéon 'bone'), literally meaning "Dunkle's bone".[13]

Originally thought to be a member of the genus Dinichthys, Dunkleosteus was later recognized as belonging to its own genus in 1956. It was thought to be closely related to Dinichthys, and they were grouped together in the family Dinichthyidae. However, in the phylogenetic analysis of Carr and Hlavin (2010), Dunkleosteus and Dinichthys were found to belong to separate clades of arthrodires: Dunkleosteus belonged to a group called the Dunkleosteoidea while Dinichthys belonged to the distantly related Aspinothoracidi. Carr & Hlavin resurrected the family Dunkleosteidae and placed Dunkleosteus, Eastmanosteus, and a few other genera from Dinichthyidae within it.[14] Dinichthyidae, in turn, is left a monospecific family, though closely related to arthrodires like Gorgonichthys and Heintzichthys.[15]

The cladogram below from the study of Zhu & Zhu (2013) shows the placement of Dunkleosteus within Dunkleosteidae and Dinichthys within the separate clade Aspinothoracidi:[16]

| Eubrachythoraci |

| Pachyosteomorphi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Alternatively, the subsequent 2016 Zhu et al. study using a larger morphological dataset recovered Panxiosteidae well outside of Dunkleosteoidea, leaving the status of Dunkleosteidae as a clade grouping separate from Dunkleosteoidea in doubt, as shown in the cladogram below:[17]

| Eubrachythoraci |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Species

[edit]At least ten different species[14][18] of Dunkleosteus have been described so far. However, many of them are poorly characterized and may be synonyms of previously named species or not pertain to Dunkleosteus.[19] Dunkleosteus as currently defined is a wastebasket taxon for large dunkleosteoid arthrodires that are more evolutionarily derived than Eastmanosteus.[19]

The type species, D. terrelli, is the largest, best-known species of the genus. Size estimates for this species range from 4.1–10 m (13–33 ft) in length, though estimates greater than 4.5 m are poorly supported.[4][2] Skulls of this species can be up to 60–70 cm (24–28 in) in length.[2] D. terrelli's fossil remains are found in Upper Frasnian to Upper Famennian Late Devonian strata of the United States (Huron, Chagrin, and Cleveland Shales of Ohio, the Conneaut and Chadakoin Formations of Pennsylvania, the Chattanooga Shale of Tennessee, the Lost Burro Formation of California, and possibly the Ives breccia of Texas[18]) and Europe.

D. belgicus (?) is known from fragments described from the Famennian of Belgium. The median dorsal plate is characteristic of the genus, but, a plate that was described as a suborbital is an anterolateral.[18] Lelièvre (1982) considers this taxon a nomen dubium ("doubtful name") and suggests the material may actually pertain to Ardennosteus.[20]

D. denisoni is known from a small median dorsal plate, typical in appearance for Dunkleosteus, but much smaller than normal. It is comparable in skull structure to D. marsaisi.[18]

D. marsaisi refers to the Dunkleosteus fossils from the Lower Famennian Late Devonian strata of the Atlas Mountains in Morocco. It differs in size, the known skulls averaging a length of 35 centimetres (1.15 ft) and in form to D. terrelli. In D. marsaisi, the snout is narrower, and a postpineal fenestra may be present. Many researchers and authorities consider it a synonym of D. terrelli.[21] H. Schultze regards D. marsaisi as a member of Eastmanosteus.[18][22]

D. magnificus is a large placoderm from the Frasnian Rhinestreet Shale of New York. It was originally described as Dinichthys magnificus by Hussakof and Bryant in 1919, then as "Dinichthys mirabilis" by Heintz in 1932. Dunkle and Lane (1971) moved it to Dunkleosteus,[18] whereas Dennis-Bryan (1987) considered it to belong to the genus Eastmanosteus.[23] This species has a skull length of 55 cm (22 in) and a total estimated length of approximately 3 m (9.8 ft).[19]

D. missouriensis is known from fragments from Frasnian Missouri. Dunkle and Lane regard them as being very similar to D. terrelli.[18] In his revision of Dunkleosteus taxonomy, Hlavin (1976) considers this species to be tentatively synonymous with D. terrelli (Dunkleosteus cf. D. terrelli).[24]

D. newberryi is known primarily from a 28 centimetres (11 in) long infragnathal with a prominent anterior cusp, found in the Frasnian portion of the Genesee Group of New York, and originally described as Dinichthys newberryi.[18] Lebedev et al. (2023) noted D. newberryi has an unusually long marginal tooth row compared to other species of Dunkleosteus and lacks the accessory odontoids typical of this genus, suggesting it might not belong to Dunkleosteus or even Dunkleosteoidea.[19]

D. amblyodoratus is known from some fragmentary remains from Late Devonian strata of Kettle Point Formation, Ontario. The species name means 'blunt spear' and refers to the way the nuchal and paranuchal plates in the back of the head form the shape of a blunted spearhead.[14]

D. raveri is a small species, possibly 1 meter long, known from an uncrushed skull roof found in a carbonate concretion from near the bottom of the Huron Shale, of the Famennian Ohio Shale strata. Besides its small size, it had comparatively large eyes. Because D. raveri was found in the strata directly below the strata where the remains of D. terrelli are found, D. raveri may have given rise to D. terrelli. The species name commemorates Clarence Raver of Wakeman, Ohio, who discovered the concretion containing the holotype.[14]

D. tuderensis is known from an infragnathal found in the lower-middle Famennian-aged Bilovo Formation of the Tver Region in northwest Russia. The specific name refers to the Maliy Tuder River as the holotype was found on its bank.[19]

In total, of the ten or so species listed above only four are agreed upon as valid species of Dunkleosteus by all researchers: D. terrelli (which may or may not include Dunkleosteus material from Morocco), D. raveri, D. tuderensis, and possibly D. amblyodoratus (which is known from limited material that appears distinct but is difficult to compare with other dunkleosteids). The taxonomy of early late Devonian (Frasnian) species is poorly established, whereas latest Devonian (Famennian) species are easily referable to this genus. This is not counting additional material assigned to Dunkleosteus sp. from the Famennian of California, Texas, Tennessee, and Poland.[19][25]

Description

[edit]Size and anatomy

[edit]

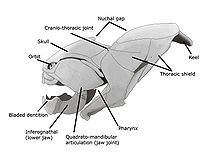

Dunkleosteus was covered in dermal bone forming armor plates across its skull and front half of its trunk. This armor is often described as being over 2–3 inches (5.1–7.6 cm) thick,[26][14] but this is only across the thickened nuchal plate at the back of the skull.[14] Thickening of the nuchal plate is a common feature of eubrachythoracid arthrodires.[27][28] Across the rest of the body the armor is generally much thinner, only about 0.33–1 inch (0.84–2.54 cm) in thickness.[29] The plates of Dunkleosteus had both a hard cortical and a marrow-filled cancellous layer, unlike most teleost fishes and more similar to tetrapod bones.[2][30]

Mainly the armored frontal sections of specimens have been fossilized, and consequently, the appearance of the other portions of the fish is mostly unknown.[31] In fact, only about 5% of Dunkleosteus specimens have more than a quarter of their skeleton preserved.[32] Because of this, many reconstructions of the hindquarters are often based on fossils of smaller arthrodires, such as Coccosteus, which have preserved hind sections,[2] leading to widely varying size estimates.[2]

Dunkleosteus terrelli is one of the largest known placoderms, with its maximum size being variably estimated as anywhere from 4.1–10 metres (13–33 ft) by different researchers.[33][34][12][35][2] However, most cited length estimates are speculative and lack quantitative or statistical backing, and lengths of 5 m (16 ft) or more are poorly supported.[12][2] Most studies that estimate the length of Dunkleosteus terrelli do not provide information as to how these estimates were calculated, the measurements used to scale them, or which specimens were examined. Estimates in these studies are implied to be based on either CMNH 5768 (the largest complete armor of D. terrelli) or CMNH 5936 (the largest known jaw fragment). Additionally, these reconstructions often require Dunkleosteus to lack many features consistent across the body plans of other arthrodires like Coccosteus and Amazichthys.[3]

The most extensive analyses of body size and shape in Dunkleosteus terrelli produce length estimates of ~3.4 metres (11 ft) for typical adults of this species, with very rare and exceptional individuals potentially reaching lengths of 4.1 metres (13 ft).[2][3] These estimates were calculated using several different size proxies (head length, orbit-opercular length [head length minus snout length], ventral shield length, entering angle, locations of the pectoral and pelvic girdles relative to total length), which produce largely similar results.[2][3] Statistical margins of error in these methods mean lengths as great as 3.7 metres (12 ft) in typical adults and 4.5 metres (15 ft) for exceptional individuals remain possible, but greater lengths result in proportions largely outside what is seen in other arthrodires and jawed fishes more generally, especially in terms of the size of the head and trunk armor relative to the total length of the animal and the relative location of the pectoral and pelvic fins.[2][3] Indeed, the implied proportions under the upper ranges of the margins of error suggest even those lengths may be overly generous.[3] Lengths at the lower end of the margins of error are unlikely given the preserved lengths of the head and trunk armor.[2]

Most studies with well-defined methods produce lengths of 5 metres (16 ft) or less for Dunkleosteus terrelli,[2] with the exception of Ferrón et al. (2017), which produces larger estimates of 6.88–8.79 metres (22.6–28.8 ft) based on upper jaw perimeter of modern sharks.[12] However, arthrodires have proportionally larger mouths than modern sharks, making the lengths estimated by Ferrón et al. (2017) unreliable.[4] Upper jaw perimeter overestimates the size of complete arthrodires like Coccosteus and the estimates of Ferrón et al. (2017) result in Dunkleosteus having an extremely small head and hyper-elongate trunk relative to the known dimensions of the fossils.[4] The reconstruction presented in Ferrón et al. (2017) is also incorrectly scaled to the known dimensions of the fossil material; if scaled to the size of CMNH 5768, it produces a length of 3.77 metres (12.4 ft), agreeing with the shorter estimates in later studies.[4]

Carr (2010) estimated a 4.6 metres (15 ft) long adult individual of Dunkleosteus terrelli to have weighed 665 kilograms (1,466 lb), assuming a shark-like body plan and a similar length-weight relationship.[36] Engelman (2023), using an ellipsoid volumetric method, estimated weights of 950–1,200 kilograms (2,090–2,650 lb) for typical (3.41 metres (11.2 ft) long) adult Dunkleosteus, and weights of 1,494–1,764 kilograms (3,294–3,889 lb) for the largest (4.1 metres (13.5 ft) in this study) individual.[2] The higher weights by Engelman (2023) are mostly a result of the fact that arthrodires tend to have relatively deeper and wider bodies compared to sharks.[2]

An exceptionally preserved specimen of D. terrelli preserves a pectoral fin outline with ceratotrichia, implying that the fin morphology of placoderms was much more variable than previously thought, and was heavily influenced by locomotory requirements. This knowledge, coupled with the knowledge that fish morphology is more heavily influenced by feeding niche than phylogeny, allowed a 2017 study to infer the caudal fin shape of D. terrelli, reconstructing this fin with a strong ventral lobe, a high aspect ratio, narrow caudal peduncle, in contrast to previous reconstructions based on the anguilliform caudal fin of coccosteomorph placoderms.[12]

The only vertebral remains known for Dunkleosteus are a small series of 16 vertebrae within the trunk armor of the specimen CMNH 50322.[37] Most of these vertebrae are highly fused, and have very prominent, laterally-projecting articular facets compared to other arthrodires.[3][37] Although many arthrodires show the incorporation of anterior vertebrae into a synarcual, in these species the fused region is small whereas the fused region of Dunkleosteus extends almost to the end of the trunk armor, which would make its spine very stiff.[37][3] This, along with a ridge on the inside of the trunk armor suggesting an unusually well-developed attachment for the horizontal septum, suggests Dunkleosteus may have had an anteriorly stiffened spine and specialized connective tissues to transmit force generated by the anterior trunk muscles to the tail fin, similar to thunniform vertebrates like lamnids and tunas.[3]

The pelvic girdle of Dunkleosteus is relatively small relative to the overall size of the armor.[3] Several specimens preserve associated pelvic girdles, but their original position was not recorded during preservation.[3] However, because these specimens were excavated from cliff faces, they were probably found in close to the armor, suggesting these fins were associated with the end of the ventral shield as in other arthrodires.[3] One specimen may preserve pelvic fin basals near the end of the trunk armor.[3]

Length estimations of D. terrelli

[edit]| Study (author) | Year | Length | Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newberry | 1875 | 4.5–5.5 metres (15–18 ft) | Extrapolated from Coccosteus cuspidatus, measurements and specimen used unclear | [5] |

| Newberry | 1889 | 4.5 metres (15 ft) | Unstated (implied extrapolation from Coccosteus) | [38] |

| Dean | 1895 | 3 metres (9.8 ft) | Methods, measurements, and specimens unstated | [39] |

| Hussakof | 1905 | 1.67 metres (5.5 ft) (AMNH FF 195) 3.79 metres (12.4 ft) (extrapolated to CMNH 5768 by Engelman 2023[2] assuming similar head-trunk proportions) | Entering angle of body | [40] |

| Anonymous | 1923 | 7.6 metres (25 ft) | Methods, measurements, and specimens used not stated | [41] |

| Hyde | 1926 | 4.5–6 metres (15–20 ft) | Methods, measurements, and specimens used not stated | [42] |

| Romer | 1966 | 9 metres (30 ft) | Methods, measurements, and specimens used not stated | [43] |

| Colbert | 1969 | 9 metres (30 ft) | Methods, measurements, and specimens used not stated | [44] |

| Denison | 1978 | 6 metres (20 ft) | Methods, measurements, and specimens used not stated | [18] |

| Williams | 1992 | 5 metres (16 ft) | Methods, measurements, and specimens used not stated | [45] |

| Janvier | 2003 | 6–7 metres (20–23 ft) | Methods, measurements, and specimens used not stated | [46] |

| Young | 2003 | 6 metres (20 ft) | Methods, measurements, and specimens used not stated | [47] |

| Anderson and Westneat | 2007 | 6 metres (20 ft) | Methods, measurements, and specimens used not stated | [33] |

| Anderson and Westneat | 2009 | 10 metres (33 ft) | Methods, measurements, and specimens used not stated | [34] |

| Carr | 2010 | 4.5–6 metres (15–20 ft) | Methods, measurements, and specimens used not stated | [36] |

| Long | 2010 | 4.5–8 metres (15–26 ft) | Methods, measurements, and specimens used not stated | [48] |

| Sallan and Galimberti | 2015 | 8 metres (26 ft) | Methods, measurements, and specimens used not stated | [49] |

| Ferrón et al. | 2017 | 6.88 metres (22.6 ft) (average adult, CMNH 5768) 8.79 metres (28.8 ft) (largest individual, CMNH 5936) | Upper jaw perimeter | [12] |

| Long et al. | 2019 | 6–8 metres (20–26 ft) | Methods, measurements, and specimens used not stated | [50] |

| Johanson et al. | 2019 | 3 metres (9.8 ft) (CMNH 50322) 7.1 metres (23 ft) (extrapolated to CMNH 5768 by Engelman 2023 assuming similar head-trunk proportions) | Methods and measurements not stated | [37] |

| Engelman | 2023 | 3.41 metres (11.2 ft) (average adult, CMNH 5768) 4.1 metres (13.5 ft) (largest individual, CMNH 5936) | Orbit-opercular length (head length minus snout) | [2] |

| Engelman | 2023 | 3.41 metres (11.2 ft) (average adult, CMNH 5768) | Skull length in Coccosteus | [2] |

| Engelman | 2023 | 5.23 metres (17.2 ft) (average adult, CMNH 5768) | Infragnathal length in Coccosteus (source considers this estimate unreliable due to Dunkleosteus having a relatively larger mouth than Coccosteus) | [2] |

| Engelman | 2023 | 3.47 metres (11.4 ft) (average adult, CMNH 5768) | Entering angle of body | [2] |

| Engelman | 2023 | 3.88 metres (12.7 ft) (average adult, CMNH 5768) | Length of posteroventrolateral plate | [2] |

| Engelman | 2023 | 3.40 metres (11.2 ft) (average adult, CMNH 5768) | Inferred location of pelvic girdle | [2] |

Paleobiology

[edit]Diet

[edit]

Dunkleosteus terrelli possessed a four-bar linkage mechanism for jaw opening that incorporated connections between the skull, the thoracic shield, the lower jaw and the jaw muscles joined by movable joints.[34][33] This mechanism allowed D. terrelli to both achieve a high speed of jaw opening, opening their jaws in 20 milliseconds and completing the whole process in 50–60 milliseconds (comparable to modern fishes that use suction feeding to assist in prey capture[33]) and producing high bite forces when closing the jaw, estimated at 4,414 N (450 kgf; 992 lbf) at the tip and 5,363 N (547 kgf; 1,206 lbf) at the blade edge,[33] or even up to 6,170 N (629 kgf; 1,387 lbf) and 7,495 N (764 kgf; 1,685 lbf) respectively.[34] The bite force is considered the highest of any living or fossil fish, and among the highest of any animal.[33] The pressures generated in those regions were high enough to puncture or cut through cuticle or dermal armor,[33] suggesting that D. terrelli was adapted to prey on free-swimming, armored prey such as ammonites and other placoderms.[34]

In addition, teeth of a chondrichthyan thought to belong to Orodus (Orodus spp.) were found in association with Dunkleosteus remains, suggesting that these were probably stomach contents regurgitated from the animal. Orodus is thought to be tachypelagic, or a fast-swimming pelagic fish. Thus, Dunkleosteus might have been fast enough to catch these fast organisms, and not a slow swimmer like originally thought.[12] Fossils of Dunkleosteus are frequently found with boluses of fish bones, semidigested and partially eaten remains of other fish.[51] As a result, the fossil record indicates it may have routinely regurgitated prey bones rather than digest them. Mature individuals probably inhabited deep sea locations, like other placoderms, living in shallow waters during adolescence.[52]

A specimen of Dunkleosteus (CMNH 5302), and Titanichthys (CMNH 9889), show damage said to be puncture damage from the bony fangs of other Dunkleosteus.[34]

Reproduction

[edit]Dunkleosteus, together with most other placoderms, may have also been among the first vertebrates to internalize egg fertilization, as seen in some modern sharks.[53] Some other placoderms have been found with evidence that they may have been viviparous, including what appears to have been an umbilical cord.[54]

Growth

[edit]Morphological studies on the lower jaws of juveniles of D. terrelli reveal they were proportionally as robust as those of adults, indicating they already could produce high bite forces and likely were able to shear into resistant prey tissue similar to adults, albeit on a smaller scale. This pattern is in direct contrast to the condition common in tetrapods in which the jaws of juveniles are more gracile than in adults.[55]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Tamisiea, Jack (4 March 2023). "Dunk Was Chunky, but Still Deadly". New York Times. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Engelman, Russell K. (2023). "A Devonian Fish Tale: A New Method of Body Length Estimation Suggests Much Smaller Sizes for Dunkleosteus terrelli (Placodermi: Arthrodira)". Diversity. 15 (3): 318. doi:10.3390/d15030318. ISSN 1424-2818.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Engelman, Russell K. (2024). "Reconstructing Dunkleosteus terrelli (Placodermi: Arthrodira): A new look for an iconic Devonian predator". Palaeontologia Electronica. doi:10.26879/1343.

- ^ a b c d e Engelman, Russell (10 April 2023). "Giant, swimming mouths: oral dimensions of extant sharks do not accurately predict body size in Dunkleosteus terrelli (Placodermi: Arthrodira)". PeerJ. 11: e15131. doi:10.7717/peerj.15131. PMC 10100833. PMID 37065696.

- ^ a b c Newberry, John S. (1875). "Descriptions of fossil fishes". Report of the Geological Survey of Ohio. Volume II. Geology and Paleontology. Vol. 2. Columbus: Nevins and Myers, State Printers. p. 24.

- ^ "Dunkleosteus terrelli: Fierce prehistoric predator" page at Cleveland Museum of Natural History. https://www.cmnh.org/dunk Archived 19 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Claypole, E. W. (1893). "The three great fossil placoderms of Ohio". American Geologist. 12: 89–99.

- ^ "Dunkleosteus terrelli: Fierce prehistoric predator". Cleveland Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 19 May 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ "Dunkleosteus". American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ "Collections Catalog of the Department of Paleobiology of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ "Collections Database of the Yale Peabody Museum". Yale Peabody Museum. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ferrón, Humberto G.; Martínez-Pérez, Carlos; Botella, Héctor (2017). "Ecomorphological inferences in early vertebrates: reconstructing Dunkleosteus terrelli (Arthrodira, Placodermi) caudal fin from palaeoecological data". PeerJ. 5: e4081. doi:10.7717/peerj.4081. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 5723140. PMID 29230354.

- ^ Lehman, Jean-Pierre (1956), "Les arthrodires du Dévonien supérieur du Tafilalet (Sud Marocain)", Notes et Mémoires. Service Géologique du Maroc (in French), 129: 1–170

- ^ a b c d e f Carr R. K., Hlavin V. J. (2010). "Two new species of Dunkleosteus Lehman, 1956, from the Ohio Shale Formation (USA, Famennian) and the Kettle Point Formation (Canada, Upper Devonian), and a cladistic analysis of the Eubrachythoraci (Placodermi, Arthrodira)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 159 (1): 195–222. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00578.x.

- ^ Carr, Robert K.; William J. Hlavin (2 September 1995). "Dinichthyidae (Placodermi):A paleontological fiction?". Geobios. 28: 85–87. Bibcode:1995Geobi..28...85C. doi:10.1016/S0016-6995(95)80092-1.

- ^ You-An Zhu; Min Zhu (2013). "A redescription of Kiangyousteus yohii (Arthrodira: Eubrachythoraci) from the Middle Devonian of China, with remarks on the systematics of the Eubrachythoraci". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 169 (4): 798–819. doi:10.1111/zoj12089.

- ^ Zhu, You-An; Zhu, Min; Wang, Jun-Qing (1 April 2016). "Redescription of Yinostius major (Arthrodira: Heterostiidae) from the Lower Devonian of China, and the interrelationships of Brachythoraci". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 176 (4): 806–834. doi:10.1111/zoj.12356. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Denison, Robert (1978). "Placodermi". Handbook of Paleoichthyology. Vol. 2. Stuttgart New York: Gustav Fischer Verlag. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-89574-027-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Lebedev, Oleg A.; Engelman, Russell K.; Skutschas, Pavel P.; Johanson, Zerina; Smith, Moya M.; Kolchanov, Veniamin V.; Trinajstic, Kate; Linkevich, Valeriy V. (May 2023). "Structure, Growth and Histology of Gnathal Elements in Dunkleosteus (Arthrodira, Placodermi), with a Description of a New Species from the Famennian (Upper Devonian) of the Tver Region (North-Western Russia)". Diversity. 15 (5): 648. doi:10.3390/d15050648. ISSN 1424-2818.

- ^ Lelièvre, Hervé (1982). "Ardennosteus ubaghsi n.g., n. sp. Brachythoraci primitif (vertébré, placoderme) du Famennien d'Esneux (Belgique)". Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique. 105 (1).

- ^ Murray, A.M. (2000). "The Palaeozoic, Mesozoic and Early Cenozoic fishes of Africa". Fish and Fisheries. 1 (2): 111–145. Bibcode:2000AqFF....1..111M. doi:10.1046/j.1467-2979.2000.00015.x.

- ^ Schultz, H (1973). "Large Upper Devonian arthrodires from Iran". Fieldiana Geology. 23: 53–78. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.5270.

- ^ Dennis-Bryan, Kim (1987). "A new species of eastmanosteid arthrodire (Pisces: Placodermi) from Gogo, Western Australia". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 90 (1): 1–64. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1987.tb01347.x.

- ^ Hlavin, William J. (1976). Biostratigraphy of the Late Devonian black shales of the cratonal margin of the Appalachian geosyncline (PhD thesis).

- ^ Dunkle; Lane, N.G. (1971). "Devonian fishes from California. Kirtlandia". Kirtlandia. 15: 1–5.

- ^ Mangels, John. "My, What A Big Mouth You Have". Cleveland Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ Miles, Roger S. (1969). "Features of Placoderm Diversification and the Evolution of the Arthrodire Feeding Mechanism". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 68 (6): 123–170. doi:10.1017/S0080456800014629.

- ^ Stensiö, Erik A. "Anatomical studies on the arthrodiran head. Pt. 1. Preface, geological and geographical distribution, the organisation of the arthrodires, the anatomy of the head in the Dolichothoraci, Coccosteomorphi and Pachyosteomorphi". Kungligar Svenska Vetenskapakadamiens Handlingar. 9: 1–419.

- ^ "Specimen Data – UMORF University of Michigan Online Repository of Fossils". UMORF. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ Giles, Sam; Rücklin, Martin; Donoghue, Philip C.J. (June 2013). "Histology of "placoderm" dermal skeletons: Implications for the nature of the ancestral gnathostome". Journal of Morphology. 274 (6): 627–644. doi:10.1002/jmor.20119. PMC 5176033. PMID 23378262.

- ^ Dash, Sean (2008). Prehistoric Monsters Revealed. United States: Workaholic Productions / History Channel. Retrieved 18 December 2015.[dead YouTube link]

- ^ Carr, R, & G.L. Jackson. 2008. The Vertebrates fauna of the Cleveland member (Famennian) of the Ohio Shale. Society of Vertebrates Paleontology. 1–17.

- ^ a b c d e f g Anderson, P.S.L.; Westneat, M. (2007). "Feeding mechanics and bite force modelling of the skull of Dunkleosteus terrelli, an ancient apex predator". Biology Letters. 3 (1): 76–79. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0569. PMC 2373817. PMID 17443970.

- ^ a b c d e f Anderson, P.S.L.; Westneat, M. (2009). "A biomechanical model of feeding kinematics for Dunkleosteus terrelli (Arthrodira, Placodermi)" (PDF). Paleobiology. 35 (2): 251–269. Bibcode:2009Pbio...35..251A. doi:10.1666/08011.1. S2CID 86203770. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ Williams, Nigel (2007). "Force feeding". Current Biology. 17 (1): R3. Bibcode:2007CBio...17...R3W. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.11.057. S2CID 36585467.

- ^ a b Carr, Robert K. (2010). "Paleoecology of Dunkleosteus terrelli (Placodermi: Arthrodira)". Kirtlandia. 57.

- ^ a b c d Johanson, Zerina; Trinajstic, Kate; Cumbaa, Stephen; Ryan, Michael (2019). "Fusion in the vertebral column of the pachyosteomorph arthrodire Dunkleosteus terrelli ('Placodermi')". Palaeontologia Electronica. 22.2.20A: 1–13. doi:10.26879/872. S2CID 162173408.

- ^ Newberry, John S. (1889). "Paleozoic fishes of North America". Monographs of the U.S. Geological Survey. 16: 24.

- ^ Dean, Bashford (1895). Fishes, Living and Fossil: An Outline of Their Forms and Probable Relationships. London: Macmillan and Company. p. 130.

- ^ Hussakof, Louis (1905). "Notes on the Devonian "placoderm" Dinichthys intermedius Newb". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 21: 27–36.

- ^ Anonymous (1923). "Cleveland shale fishes". Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. 9: 36.

- ^ Hyde, Jesse E. (1926). "Collecting fossil fishes from the Cleveland Shale". Natural History. 26: 497–504.

- ^ Romer, Alfred S. (1966). Vertebrate Paleontology (3rd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 49.

- ^ Colbert, Edwin H. (1969). Evolution of the Vertebrates: A History of Backboned Animals Through Time (2nd ed.). Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons. p. 36.

- ^ Williams, Michael E. (1992). "Jaws: The Early Years". Explorer. 34: 4–8.

- ^ Janvier, P. (2003). Early Vertebrates. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 12.

- ^ Young, Gavin C. (24 December 2003). "Did placoderm fish have teeth?". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 23 (4): 987–990. Bibcode:2003JVPal..23..987Y. doi:10.1671/31. S2CID 85572061.

- ^ Long, John A. (2010). The Rise of Fishes: 500 Million Years of Evolution (2nd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 88–90.

- ^ Sallan, Lauren; Galimberti, Andrew K. (13 November 2015). "Body-size reduction in vertebrates following the end-Devonian mass extinction". Science. 350 (6262): 812–815. Bibcode:2015Sci...350..812S. doi:10.1126/science.aac7373. PMID 26564854. S2CID 206640186.

- ^ Long, John A.; Choo, Brian; Clement, Alice (31 December 2018). "The Evolution of Fishes through Geological Time". In Johanson, Zerina; Underwood, Charlie; Richter, Martha (eds.). Evolution and Development of Fishes. pp. 3–29. doi:10.1017/9781316832172.002. ISBN 978-1-316-83217-2. S2CID 134217082.

- ^ "Dunkleosteus Placodermi Devonian Armored Fish from Morocco". Fossil Archives. The Virtual Fossil Museum. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- ^ "UWL Website".

- ^ Ahlberg, Per; Trinajstic, Kate; Johanson, Zerina; Long, John (2009). "Pelvic claspers confirm chondrichthyan-like internal fertilization in arthrodires". Nature. 460 (7257): 888–889. Bibcode:2009Natur.460..888A. doi:10.1038/nature08176. PMID 19597477. S2CID 205217467.

- ^ Long, J. A.; Trinajstic, K.; Young, G. C.; Senden, T. (2008). "Live birth in the Devonian period". Nature. 453 (7195): 650–652. Bibcode:2008Natur.453..650L. doi:10.1038/nature06966. PMID 18509443. S2CID 205213348.

- ^ Snively, E.; Anderson, P.S.L.; Ryan, M.J. (2009). "Functional and ontogenetic implications of bite stress in arthrodire placoderms". Kirtlandia. 57.

Further reading

[edit]- Anderson, Philip S. L. (2008). "Shape Variation Between Arthrodire Morphotypes Indicates Possible Feeding Niches". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (4): 961–969. Bibcode:2008JVPal..28..961A. doi:10.1671/0272-4634-28.4.961. S2CID 86583150.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch