Edward Steichen

Edward Steichen | |

|---|---|

Edward Steichen, photographed by Fred Holland Day (1901) | |

| Born | Édouard Jean Steichen March 27, 1879 Bivange/Béiweng, Luxembourg |

| Died | March 25, 1973 (aged 93) |

| Known for | Photography, Painting |

| Spouses | Clara Smith (m. 1903; div. 1922)Dana Desboro Glover (m. 1923; died 1957) |

| Children | Mary Steichen Calderone Charlotte "Kate" Rodina Steichen |

| Relatives | Lilian Steichen (sister) Carl Sandburg (brother-in-law) |

| Awards | Légion d'Honneur, Medal of Freedom |

| Website | edwardsteichen |

Edward Jean Steichen (March 27, 1879 – March 25, 1973) was a Luxembourgish American photographer, painter and curator and a pioneer of fashion photography. His gown images for the magazine Art et Décoration in 1911 were the first modern fashion photographs to be published. From 1923 to 1938, Steichen served as chief photographer for the Condé Nast magazines Vogue and Vanity Fair, while also working for many advertising agencies, including J. Walter Thompson. During these years, Steichen was regarded as the most popular and highest-paid photographer in the world.[1]

After the United States' entry into World War II, Steichen was invited by the United States Navy to serve as Director of the Naval Aviation Photographic Unit.[2] In 1944, he directed the war documentary The Fighting Lady, which won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature at the 17th Academy Awards.

From 1947 to 1961, Steichen served as Director of the Department of Photography at New York's Museum of Modern Art. While there, he curated and assembled exhibits including the touring exhibition The Family of Man, which was seen by nine million people. In 2003, the Family of Man photographic collection was added to UNESCO's Memory of the World Register in recognition of its historical value.[3]

In February 2006, a print of Steichen's early pictorialist photograph, The Pond–Moonlight (1904), sold for US$2.9 million—at the time, the highest price ever paid for a photograph at auction.[4] A print of another photograph of the same style, The Flatiron (1904), became the second most expensive photograph ever on November 8, 2022, when it was sold for $12,000,000, at Christie's New York – well above the original estimate of $2,000,000-$3,000,000.[5]

Early life

[edit]Steichen was born Éduard Jean Steichen on March 27, 1879, in a small house in the village of Bivange, Luxembourg, the son of Jean-Pierre and Marie Kemp Steichen.[6] His parents facing increasingly straitened circumstances and financial difficulties, decided to make a new start and emigrated to the United States when Steichen was eighteen months old. Jean-Pierre Steichen immigrated in 1880, with Marie Steichen bringing the infant Éduard along after Jean-Pierre had settled in Hancock in Michigan's Upper Peninsula copper country. According to noted Steichen biographer, Penelope Niven, the Steichens were "part of a large exodus of Luxembourgers displaced in the late nineteenth century by worsening economic conditions."[6]

Éduard's sister and only sibling, Lilian Steichen, was born in Hancock on May 1, 1883. She would later marry poet Carl Sandburg, whom she met at the Milwaukee Social Democratic Party office in 1907. Her marriage to Sandburg the following year helped forge a life-long friendship and partnership between her brother and Sandburg.[7][8]

By 1889, when Éduard was 10, his parents had saved up enough money to move the family to Milwaukee.[9] There he learned German and English at school, while continuing to speak Luxembourgish at home.[10]

In 1894, at fifteen, Steichen began attending Pio Nono College, a Catholic boys' high school, where his artistic talents were noticed. His drawings in particular were said to show promise.[11] He quit high school to begin a four-year lithography apprenticeship with the American Fine Art Company of Milwaukee.[12] After hours, he would sketch and draw, and he began to teach himself painting.[13] Having discovered a camera shop near his work, he visited frequently until he persuaded himself to buy his first camera, a secondhand Kodak box "detective" camera, in 1895.[14] Steichen and his friends who were also interested in drawing and photography pooled their funds, rented a small room in a Milwaukee, WI office building, and began calling themselves the Milwaukee Art Students League.[15] The group hired Richard Lorenz and Robert Schade for occasional lectures.[12] In 1899, Steichen's photographs were exhibited in the second Philadelphia Photographic Salon.[16]

Steichen became a U.S. citizen in 1900 and signed the naturalization papers as Edward J. Steichen, but he continued to use his birth name of Éduard until after the First World War.[17]

Career

[edit]Paris, New York, and Partnerships with Stieglitz and Rodin

[edit]

In April 1900, Steichen left Milwaukee for Paris to study art. Clarence H. White thought Steichen and Alfred Stieglitz should meet, and thus produced an introduction letter for Steichen, and Steichen—then en route to Paris from his home in Milwaukee—met Stieglitz in New York City in early 1900.[18] In that first meeting, Stieglitz expressed praise for Steichen's background in painting and bought three of Steichen's photographic prints.[19]

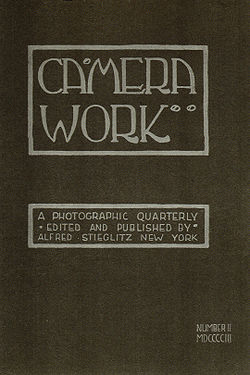

In 1902, when Stieglitz was formulating what would become Camera Work, he asked Steichen to design the logo for the magazine with a custom typeface.[20] Steichen was the most frequently shown photographer in the journal.

Steichen began experimenting with color photography in 1904 and was one of the earliest in the United States to use the Autochrome Lumière process.[21] In 1905, Stieglitz and Steichen created the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, in what had been Steichen's portrait studio;[22] it eventually became known as the 291 Gallery after its address. It presented some of the first American exhibitions of Auguste Rodin, Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, and Constantin Brâncuși.

According to author and art historian William A. Ewing, Steichen became one of the earliest "jet setters", constantly moving back and forth between Europe and the U.S. by steamship, in the process cross-pollinating art from Europe to the United States, helping to define photography as an art form, and at the same time widening America's understanding of European art and art in general.[23]

Pioneering fashion photography

[edit]Fashion photography began with engravings reproduced from photographs of modishly-dressed actresses by Leopold-Emile Reutlinger, Nadar and others in the 1890s. After high-quality half-tone reproduction of photographs became possible, most credit as pioneers of the genre goes to the French Baron Adolph de Meyer and to Steichen who, borrowing his friend's hand-camera in 1907, candidly photographed dazzlingly-dressed ladies at the Longchamp Racecourse[24][25] Fashion then was being photographed for newspaper supplements and fashion magazines, particularly by the Frères Séeberger,[25] as it was worn at Paris horse-race meetings by aristocracy and hired models.

In 1911, Lucien Vogel, the publisher of Jardin des Modes and La Gazette du Bon Ton, challenged Steichen to promote fashion as a fine art through photography.[26] Steichen took photos of gowns designed by couturier Paul Poiret, which were published in the April 1911 issue of the magazine Art et Décoration.[27][26] Two were in colour,[28][29] and appeared next to flat, stylised, yellow-and-black Georges Lepape drawings of accessories, fabrics, and girls.[30]

Steichen himself, in his 1963 autobiography, asserted that his 1911 Art et Décoration photographs "were probably the first serious fashion photographs ever made,"[31] a generalised claim since repeated by many commentators. What he (and de Meyer)[30] did bring was an artistic approach; a soft-focus, aesthetically retouched Pictorialist style that was distinct from the mechanically sharp images made by his commercial colleagues for half-tone reproduction, and that he and the publishers and fashion designers for whom he worked appreciated as a marketable idealisation of the garment, beyond the exact description of fabrics and buttonholes.[30]

After World War I, during which he commanded the photographic division of the American Expeditionary Forces, he gradually reverted to straight photography. In the early 1920s, Steichen famously took over 1000 photographs of a single cup and saucer, on "a graduated scale of tones from pure white through light and dark greys to black velvet," which he compared to the a musician's finger exercises.[32] He was hired by Condé Nast in 1923 for the extraordinary salary of $35,000 (equivalent to over $500,000 in 2019 value).[30]

World War II

[edit]

At the commencement of World War II, Steichen, then in his sixties, had retired[33] as a full-time photographer. He was developing new varieties of delphinium, which in 1936 had been the subject of his first exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, and the only flower exhibition ever held there.[34]

When the United States joined the global conflict, Steichen, who had come out of the first World War an Army Colonel, was refused for active service because of his age.[35] Later, invited by the Navy to serve as Director of the Naval Aviation Photographic Unit,[36][37][38] he was commissioned a Lieutenant-Commander in January 1942. Steichen selected for his unit six officer-photographers from the industry (sometimes irreverently called "Steichen's chickens"), including photographers Wayne Miller and Charles Fenno Jacobs.[39] A collection of 172 silver gelatin photographs taken by the Unit under his leadership is held at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin.[33] Their war documentary The Fighting Lady, directed by Steichen, won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature at the 17th Academy Awards.

In 1942, Steichen curated for the Museum of Modern Art the exhibition Road to Victory, five duplicates of which toured the world. Photographs in the exhibition were credited to enlisted members of the Navy, Coast Guard, and Marine Corps and numbers by Steichen's unit, while many were anonymous and some were made by automatic cameras in Navy planes operated while firing at the enemy.[40] This was followed in January 1945 by Power in the Pacific: Battle Photographs of our Navy in Action on the Sea and In the Sky.[41] Steichen was released from Active Duty (under honorable conditions) on December 13, 1945, at the rank of Captain. For his service during World War II, he was awarded the World War II Victory Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal (with 2 campaign stars), American Campaign Medal, and numerous other awards.

Museum of Modern Art

[edit]In the summer of 1929, Museum of Modern Art director Alfred H. Barr, Jr. had included a department devoted to photography in a plan presented to the Trustees. Though not put in place until 1940, it became the first department of photography in a museum devoted to twentieth-century art and was headed by Beaumont Newhall. On the strength of attendances of his propaganda exhibitions Road to Victory[42] and Power in the Pacific, and precipitating curator Newhall's resignation along with most of his staff, in 1947 Steichen was appointed Director of Photography until 1962, later assisted by Grace M. Mayer.

His appointment was protested by many who saw him as anti-art photography, one of the most vocal being Ansel Adams who on April 29, 1946, wrote a letter to Stephen Clark (copied to Newhall) to express his disappointment over Steichen's hiring for the new position of director; "To supplant Beaumont Newhall, who has made such a great contribution to the art through his vast knowledge and sympathy for the medium, with a regime which is inevitably favorable to the spectacular and 'popular' is indeed a body blow to the progress of creative photography."[43]

Nevertheless, Ansel Adams' image Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico was first published in U.S. Camera Annual 1943, after being selected by Steichen, who was serving as judge for the publication.[44] This gave Moonrise an audience before its first formal exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1944.[45]

Steichen as director held a strong belief in the local product, of the "liveness of the melting pot of American photography," and worked to expand and organise the collection, inspiring and recognising the 1950s generation while keeping historical shows to a minimum. He worked with Robert Frank even before his The Americans was published, exhibited the early work of Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind, and purchased two prints by Robert Rauschenberg in 1952, ahead of any museum.[46] Steichen also kept international developments in his scope and held shows and made important acquisitions from Europe and Latin America, occasionally visiting those countries to do so. Three books were published by the Department during his tenure (The Family of Man, Steichen the Photographer, and The Bitter Years: 1935–1941: Rural America as Seen by the Photographers of the Farm Security Administration).[47][46] Despite his solid career in photography, Steichen displayed his own work at MoMA—his retrospective, Steichen the Photographer—only after he had already announced his retirement in 1961.

Among accomplishments that were to redeem initial resentment at his appointment, Steichen created The Family of Man, a world-touring Museum of Modern Art exhibition that, while arguably a product of American Cold War propaganda, was seen by 9 million visitors and still holds the record for most-visited photography exhibit. Now permanently housed and on continuous display in Clervaux (Luxembourgish: Klierf) Castle in northern Luxembourg, his country of birth, Steichen regarded the exhibition as the "culmination of his career.".[48] Comprising over 500 photos that depicted life, love and death in 68 countries, the prologue for its widely purchased catalogue was written by Steichen's brother-in-law, Carl Sandburg.[49] As had been Steichen's wish, the exhibition was donated to the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, his country of birth.

MoMA exhibitions curated or directed by Steichen

[edit]The following are exhibitions curated or directed by Steichen during his tenure as Director of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art. (References link to the exhibition page in the museum's archive, with press releases, checklists of the exhibited photographs, and installation views.)

- 1947, 30 Sep–7 Dec: Three Young Photographers: Leonard McCombe, Wayne F. Miller, Homer Page[50]

- 1948, 6 Apr–11 Jul: In and Out of Focus: A Survey of Today's Photography, "including prints by 76 [American] photographers, the first large exhibition organized by Captain Edward J. Steichen, Director of the Museum's Department of Photography."[51]

- 1948, 27 Jul–26 Sep: 50 Photographs by 50 Photographers – Landmarks in Photographic History. "50 prints from the Museum Collections that form an abbreviated history of the development of pictorial photography during the past 100 years."[52]

- 1948, 29 Sep–28 Nov: Photo-Secession (American Photography 1902–1910)[53]

- 1948/49, 30 Nov–10 Feb: Photographs by Bill Brandt, Harry Callahan, Ted Croner, Lisette Model[54]

- 1949, 8 Feb–1 May: The Exact Instant. Events and Pages in 100 Years of News Photography[55]

- 1949, 26 Apr–24 Jul: Roots of Photography, comprising works by Hill & Adamson, Julia Margaret Cameron and Henry Fox Talbot.[56]

- 1949, 26 Jul–25 Sep: Realism in Photography. Works by Ralph Steiner, Wayne F. Miller, Tosh Matsumoto, Frederick Sommer.[57]

- 1949, 11 Oct–15 Nov: Photographs by Margaret Bourke-White, Helen Levitt, Dorothea Lange, Tana Hoban, Esther Bubley, and Hazel-Frieda Larsen. "Sixty prints by 6 women photographers."[58]

- 1950, 29 Nov–15 Jan: Roots of French Photography[59]

- 1950, 24 Jan–19 Mar: Photographs of Picasso by Gjon Mili and by Robert Capa[60]

- 1950, 28 Mar–7 May: Photography Recent Acquisitions: Stieglitz, Atget[61]

- 1950, 9 May–4 Jul: Color Photography. Survey with color photographs and transparencies by more than 75 photographers.[62]

- 1950, 1 Aug–17 Sep: Photographs by 51 Photographers. More than 100 newly acquired prints.[63]

- 1950, 26 Sep–3 Dec: Photographs by Lewis Carroll[64]

- 1951, 13 Feb–22 Apr: Korea – The Impact of War in Photographs[65]

- 1951, 1 May–4 Jul: Abstraction in Photography. Featured in an Photo Arts special issue.[66]

- 1951, 12 Jul–12 Aug: 12 Photographers, with 15 prints each by Berenice Abbott, A. Adams, Atget, Mathew Brady (studio), Brandt, Callahan, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Walker Evans, Man Ray, Model, Irving Penn, Edward Weston.[67]

- 1951, 23 Aug–4 Nov: Forgotten Photographers, nearly 100 photographs from the Library of Congress by Edward S. Curtis, Frances Benjamin Johnston a. o.[68]

- 1951, 20 Nov–12 Dec: Memorable 'Life' Photographs, catalogue.[69]

- 1951/52, 29 Nov–6 Jan: Christmas Photographs, Christmas sale of prints by Adams, Callahan, Frank, Levitt, Weston a. o. for $10–25.[70]

- 1951/52, 18 Dec–24 Feb: Five French Photographers: Brassaï, Cartier-Bresson, Robert Doisneau, Izis and Willy Ronis.[71]

- 1952, 20 May–1 Sep: Diogenes with a Camera. First show of a series featuring contemporary American photographers: W. Eugene Smith, Sommer, Callahan, Weston, Esther Bubley, Eliot Porter.[72]

- 1952, 5–18 Aug: Then and Now, 50 photographs 1839–1952 displayed during the convention of the Photographic Society of America.[73]

- 1952/53, 25 Nov–8 Mar: Diogenes with a Camera II, with Adams, Lange, Tosh Matsumoto, Man Ray, Aaron Siskind, Todd Webb.[74]

- 1953, 26 Feb–1 Apr: Always the Young Strangers. 25 never before shown photographers with three to six prints each: Roy DeCarava, Saul Leiter, Leon Levinstein, Marvin E. Newman, Naomi Savage a. o. (The title is a quote by Carl Sandburg in honour of his 75th birthday.)[75]

- 1953, 26 May–23 Aug: Postwar European Photography. Over 300 photographs by 78 photographers (Eva Besnyö, Édouard Boubat, Robert Frank, Ernst Haas, Nigel Henderson, Otto Steinert, Liselotte Strelow, Jakob Tuggener, Ed van der Elsken a. o.)[76]

- 1955, 24 Jan–8 May: The Family of Man[77][49]

- 1956, 17 Jan–18 Mar: Diogenes with a Camera III, with Walker Evans, August Sander, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, and Paul Strand.[78]

- 1956, 4 Apr–3 Jun: Diogenes with a Camera IV, with Marie-Jean Beraud-Villars, Shirley Burden, William A. Garnett, and Gustav Schenk.[79]

- 1956/57, 24 Oct–13 Jan: Language of the Wall: Parisian Graffiti Photographed by Brassaï.[80]

- 1957/58, 27 Nov–15 Apr: 70 Photographers Look at New York, in collaboration with Grace Mayer[81]

- 1958/59, 26 Nov–18 Jan: Photographs from the Museum Collection, with Abbott, Brady, DeCarava, Andreas Feininger, Frank, Haas, Lewis Hine, Art Kane, Levinstein, Levitt, Jay Maisel, Jacob Riis, W. E. Smith, Webb, Weegee, Brett Weston, Winogrand, John Vachon a. m. o., as well as pictures from agencies and institutes like the U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey.[82]

- 1960, 1–16 Oct: Photographs for Collectors. Sales show with "more than 250 prints by 66 photographers...priced at $25 and up."[83]

- 1962, 30 Jan–1 Apr: Harry Callahan and Robert Frank, assisted by Grace M. Mayer. Over 200 prints, and screenings of Frank's films Pull My Daisy (1959) and The Sin of Jesus (1961).[84]

- 1962, 18 Oct–25 Nov: The Bitter Years: 1935–1941. 200 photographs selected by "Director Emeritus" Steichen (from 270,000 taken for the F.S.A.)[85]

In the latter years of his tenure after her appointment by Steichen as Assistant Curator, it was Grace M. Mayer from the Museum of the City of New York, where she had organized about 150 exhibitions,[86] who curated the shows The Sense of Abstraction (17 Feb–10 Apr 1960), co-directed by Kathleen Haven, the museum staff designer since 1955.[87] Then Mayer organized Steichens only solo-show during his time at the museum, Steichen the Photographer, (28 Mar–30 May 1961), Diogenes with a Camera V (26 Sep–12 Nov 1961), 50 Photographs by 50 Photographers, a third survey of the museum's collection (3 Apr–15 May 1962),[88] and a series of four installations called A Bid for Space (1960 to 1963), which were designed by Kathleen Haven. Haven had also been responsible for the design of The Family of Man, she worked two years on, as well as Diogenes with a Camera (II, III and IV), the exhibition of Brassaï's graffiti photographs, and the 1958 collection survey.[89]

Steichen hired John Szarkowski to be his successor at the Museum of Modern Art on July 1, 1962. On his appointment, Szarkowski promoted Mayer to Curator.

Later life

[edit]On December 6, 1963, Steichen was presented with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson.[90]

Though then 88 years old and unable to attend in person, in 1967 Steichen, as a still-active member of the copyright committee of the American Society of Magazine Photographers, wrote a submission to the U.S. Senate hearings to support copyright law revisions, requesting that "this young giant among the visual arts be given equal rights by having its peculiar problems taken into account."[91]

In 1968, the Edward Steichen Archive was established in MoMA's Department of Photography. The Museum's then-Director René d'Harnoncourt declared that its function was to "amplify and clarify the meaning of Steichen's contribution to the art of photography, and to modern art generally."[24] Creator of the Archive was Grace M. Mayer, who in 1959 started her career as an assistant to the director, Steichen, and who became Curator of Photography in 1962, retiring in 1968. Mayer returned after her retirement to serve in a voluntary capacity as Curator of the Edward Steichen Archive until the mid-1980s to source materials by, about, and related to Steichen. Her detailed card catalogs are housed in the Museum's Grace M. Mayer Papers.[92]

Steichen's 90th birthday was marked with a dinner gathering of photographers, editors, writers, and museum professionals at the Plaza Hotel in 1969. The event was hosted by MoMA trustee Henry Allen Moe, and U.S. Camera magazine publisher Tom Maloney.[24]

In 1970, an evening show was presented in Arles during The Rencontres d'Arles festival: Edward Steichen, photographe by Martin Boschet.

Steichen bought a farm that he called Umpawaug in 1928, just outside West Redding, Connecticut.[93] He lived there until his death on March 25, 1973, two days before his 94th birthday.[94] After his death, Steichen's farm was made into a park, known as Topstone Park.[95] As of 2018, Topstone Park was open seasonally.[96]

Legacy

[edit]

"I consider Steichen a very great artist and the leading, the greatest photographer of the time. Before him, nothing conclusive had been achieved."[97]

Steichen's career, especially his activities at MoMA, did much to popularise and promote the medium, and both before and since his death photography, including his own, continued to appreciate as a collectible art form.[46]

In February 2006, a print of Steichen's early pictorialist photograph, The Pond–Moonlight (1904), sold for what was then the highest price ever paid for a photograph at auction, US$2.9 million.

Steichen took the photograph in Mamaroneck, New York, near the home of his friend, art critic Charles Caffin. It shows a wooded area and pond, with moonlight appearing between the trees and reflecting on the pond. While the print appears to be a color photograph, the first true color photographic process, the autochrome process, was not available until 1907. Steichen created the impression of color by manually applying layers of light-sensitive gums to the paper. Only three prints of The Pond–Moonlight are still known to exist and, as a result of the hand-layering of the gums, each is unique. (The two prints not auctioned are held in museum collections.) The extraordinary sale price of the print is in part attributable to its one-of-a-kind character and to its rarity.[98]

A show of early color photographs by Steichen was held at the Mudam (Musée d'Art moderne) in Luxembourg City from July 14 to September 3, 2007.[99]

Personal life

[edit]Steichen married Clara E. Smith (1875–1952) in 1903. They had two daughters, Mary Rose Steichen (1904-1998) and Charlotte "Kate" Rodina Steichen (1908-1988). In 1914, Clara accused her husband of having an affair with artist Marion H. Beckett, who was staying with them in France. The Steichens left France just ahead of invading German troops. In 1915, Clara Steichen returned to France with her daughter Kate, staying in their house in the Marne in spite of the war. Steichen returned to France with the Photography Division of the American Army Signal Corps in 1917, whereupon Clara returned to the United States. In 1919, Clara Steichen sued Marion Beckett for having an affair with her husband, but was unable to prove her claims.[100][101] Clara and Edward Steichen eventually divorced in 1922.

Steichen married Dana Desboro Glover in 1923. She died of leukemia in 1957.

In 1960, aged 80, Steichen married 27-year-old Joanna Taub and remained married to her until his death, two days before his 94th birthday. Joanna Steichen died on July 24, 2010, in Montauk, New York, aged 77.[102]

Exhibitions

[edit]Solo

[edit]- 1900: Photo Club. Paris[103]

- 1900: Mrs. Arthur Robinson's home. Milwaukee (US)[103]

- 1901: La Maison des Artistes, Paris[103]

- 1902: Photo-Club, Paris[103]

- 1902: Eduard Steichen, Paintings and Photographs, Maison des Artistes, Paris[103]

- 1905: Photo-Secession Gallery, New York[103]

- 1906: Photographs by Eduard Steichen, Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession (291 Gallery), New York[46]

- 1908: Eduard Steichen, Photographs in Monochrome and Color, Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, New York[46]

- 1909: Photo-Secession Gallery, New York[103]

- 1910: Photo-Secession Gallery, New York[103]

- 1910: Montross Gallery, London[103]

- 1910: Little Gallery, New York[103]

- 1915: M. Knoedler & Company, New York, including the murals for the Park Ave. town house of Agnes and Eugene Meyer[103][104]

- 1938: Museum of Modern Art, New York[103]

- 1938: Edward Steichen, Retrospective, Baltimore Museum of Art[46][103]

- 1950: Edward Steichen, Retrospective, American Institute of Architects Headquarters, Washington, D.C.[46]

- 1961: Steichen the Photographer, Museum of Modern Art, New York[103]

- 1963: condensed versions in Cologne, Germany, and Zurich, Switzerland[105]

- 1965: Retrospective, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris[103]

- 1976: Allan Frumkin Gallery, Chicago[103]

- 1978: Museum of Modern Art, New York[103]

- 1979: George Eastman House, Rochester, New York[103]

- 1997–2005: Hollywood Celebrity: Edward Steichen's Vanity Fair Photographs

- 1997/98, 25 Oct–12 Apr: George Eastman House, Rochester, NY

- 2004, 17 Jan–25 Apr: Kunsthal Rotterdam, Netherlands[106]

- 2005, 14 Mar–14 May: Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow, Russia[107]

- 2000: Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. First major posthumous retrospective,[46][108][109] catalogue

- 2002: Edward Steichen: Art as Advertising/ Advertising as Art, Norsk Museum for Fotografi-Preus Fotomuseum, Horten, Norway[46]

- 2005: Edward Steichen, Luxembourg Embassy, Berlin[110]

- 2007–2008: Edward Steichen: Lives in Photography / Une épopée photographique, curated by William A. Ewing and Todd Brandow for the Foundation for the Exhibition of Photography, Minneapolis, and Musée de l'Elysée, Lausanne, in collaboration with Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía,[111] catalogue[112]

- 2007, 9 Oct–30 Dec: Jeu de paume, Paris, France[113]

- 2008, 17 Jan–23 Mar: Musée de l'Elysée, Lausanne, Switzerland[114]

- 2008, 12 Apr–8 Jun: Palazzo Magnani, Reggio Emilia, Italy (combined with In High Fashion (The Condé Nast Years) 1923–1937)

- 2008, 24 Jun–22 Sep: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, Spain[115]

- 2008–2015: Edward Steichen: In High Fashion (The Condé Nast Years) 1923–1937, curated by William A. Ewing, Todd Brandow and Nathalie Herschdorfer, catalogue

- 2008, 11 Jan–30 Mar: Kunsthaus Zürich, Switzerland, catalogue

- 2008, 1 May–8 Jun: Palazzo Magnani, Reggio Emilia, Italy (combined with Edward Steichen: Lives in Photography), two catalogues[116]

- 2008, 11 Oct –2 Jan 2009: Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, Germany

- 2009, 6 Jun–8 Nov: Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown (Mass)

- 2009, 16 Jan–3 May: International Center of Photography, New York

- 2009, 26 Sep–3 Jan 2010: Art Gallery of Ontario, Canada

- 2011, 20 Nov–12 Feb 2012: Fondazione Sozzani, Milan, Italy

- 2013, 26 Jan–7 Apr: Setagaya Art Museum, Yōga, Japan[117]

- 2013, 28 Jun–6 Sep: Foam Fotografiemuseum, Amsterdam

- 2014, 28 Jun–28 Sep: Art Institute of Chicago, combined with own WWI-photographs

- 2014, 31 Oct–18 Jan 2015: Photographers' Gallery, London

- 2015, 18 Feb–24 May: WestLicht, Vienna, Austria

- 2015, 9 Sep–22 Nov: Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow, Russia

- 2009, 31 Jan–17 May: Edward Steichen: The Early Years, Museum of Photographic Arts, San Diego, USA

- 2009, 20 Mar–16 May: Edward Steichen: 1915–1923, Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

- 2010, 6 Nov–16 Jan 2011: Edward Steichen: Celebrity Design, Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany, first comprehensive show of 65 photographs gifted to the museum in 1983 by Joanna Steichen[118]

- 2011, 15 Sep–29 Oct: Edward Steichen: The Last Printing, Danziger Gallery, New York

- 2012, 12 Oct–9 Feb 2013: Edward Steichen, National Museum of Photography, Copenhagen, Denmark

- 2013, 3 Aug–8 Dec: Talk of the Town: Portraits by Edward Steichen from the Hollander Collection, LACMA, Los Angeles

- 2013, 18 Oct–2 Mar 2014: Edward Steichen & Art Deco Fashion, National Gallery of Victoria, Australia

- 2013, 6 Dec–1 Aug 2014: Steichen in the 1920s and 1930s: A Recent Acquisition, Whitney Museum, New York

- 2014, 28 Jun–28 Sep: Sharp, Clear Pictures. Edward Steichen's World War I and Condé Nast Years, Art Institute of Chicago

- 2015, 8 Sep–17 Oct: Edward Steichen, Galerie Clairefontaine, Luxembourg[119]

- 2015, 13 Nov–5 Jan 2016: Making Meaning of a Legacy: Edward Steichen, Centre for Fine Arts, Brussels, Belgium

- 2016, 7 Oct–26 Mar 2017: Twentieth-Century Photographer Edward Steichen, DeCordova Museum, Lincoln (Mass)

- 2019–2024: Edward Steichen: In Exaltation of Flowers

- 2019, 20 Sep–12 Jan 2020: Orlando Museum of Art/Mennello Museum of American Art, Orlando (Fla)[120]

- 2023, 10 Mar–18 Feb 2024: Hudson River Museum, Yonkers, New York

- 2023, 14 Oct–28 Jan 2024: Edward Steichen, Retrospective, Museum of Photography, Kraków, Poland

Group

[edit]- 1900: The New School of American Photography, Royal Photographic Society, London, England and Paris, France[103]

- 1902: American Pictorial Photography, National Arts Club, New York[46]

- 1904: Salon International de Photographie, Paris.[103]

- 1905: Opening exhibition, Little Galleries of the Photo Secession, New York[46]

- 1906: Photographs Arranged by the Photo Secession, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia[46]

- 1910: The Younger American Painters, Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, New York[46]

- 1910: International Exhibit of Pictorial Photography, Albright Art Gallery, Rochester, New York[46]

- 1932: Murals by American Painters and Photographers, Museum of Modern Art, New York[46]

- 1955: The Family of Man, Museum of Modern Art, New York[103]

Gallery

[edit]- Landscape with Avenue of Trees, painting by Steichen, 1902

- Cover design, 1900, printed 1906

- Cover of Camera Work, No 2, showing Steichen's design and custom typeface. This volume was entirely devoted to his photographs.

- Self-portrait, publ. in Camera Work No 2, 1903

- Portrait of Auguste Rodin, 1902

- The Flatiron, 1904

- Portrait of Eleanora Duse, 1903, the unaltered photograph

- Eleonora Duse, a version publ. in Photographische Mitteilungen, 1903

- Portrait of Rita de Acosta Lydig, 1905

- Portrait of Clarence H. White, 1905

- Experiment in Three-Color Photography, publ. in Camera Work No 15, 1906

- On the House Boat–"The Log Cabin", 1879, color halftone print 1908

- Gertrude Käsebier, publ. in The Century Magazine, Jan 1908

- Henri Matisse and La Serpentine, Issy-les-Moulineaux, fall 1909

- Portrait of Constantin Brâncuși, taken at Steichen's home at Voulangis, 1922

- Milk Bottles – Spring, New York 1915

- Le Tournesol (The Sunflower), c. 1920, NGA, Washington

- Wind Fire – Maria-Theresa Duncan on the Acropolis, 1921

- Aircraft of Carrier Air Group 16 return to the USS Lexington, Nov 1943

Bibliography

[edit]- Sandburg, Carl; Alexander Liberman; Edward Steichen (1929), Steichen the Photographer (Ltd. ed. of 925 numbered copies with 49 photogravures, signed by both Sandburg and Steichen), Harcourt Brace, & Co..

- Steichen, Edward (1947), The Blue Ghost: A Photographic Log and Personal Narrative of the Aircraft Carrier U.S.S. Lexington in Combat Operation. Harcourt Brace, & Co.

- Steichen, Edward (1955), The Family of Man: The Greatest Photographic Exhibition of All Time (exhibition catalogue). New York: Maco Pub. Co for the Museum of Modern Art.

- Sandburg, Carl ...; René d'Harnoncourt; Grace M. Mayer (1961), Steichen the Photographer (exhibition catalogue), Museum of Modern Art.

- Steichen, Edward (1963), A Life in Photography, The Museum of Modern Art.

- Steichen, Edward, ed. (1966), Sandburg. Photographers View Carl Sandburg. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

- Longwell, Dennis, ed. (1978), Steichen: The Master Prints 1895–1914: The Symbolist Period, New York, N.Y.: Museum of Modern Art, ISBN 978-0-87070-581-6.

- Cohen DePietro, Anne (1985), The Paintings of Eduard Steichen (exhibition catalogue). Huntington, NY: The Heckscher Museum. LCCN 85-80519.

- Sandeen, Eric J. (1995), Picturing an Exhibition: The Family of Man and 1950s America. University of New Mexico Press.

- Gedrim, Ronald, ed. (1996), Edward Steichen: Selected Texts and Bibliography, Clio Press, ISBN 978-1-85109-208-6.

- Cortese, Sabina, ed. (1997), Edward Steichen. The Royal Photographic Society Collection (exhibition catalogue, Istituto di Cultura Santa Maria della Grazie, Mestre), Milan: Charta, ISBN 978-88-8158-105-4.

- Johnston, Patricia A. (1997), Real Fantasies: Edward Steichen's Advertising Photography, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-22707-1.

- Mulligan, Therese (1997), Hollywood Celebrity: Edward Steichen's Vanity Fair Photographs (exhibition catalogue). Rochester, NY: George Eastman House.

- Niven, Penelope (1997), Steichen: A Biography. New York: Clarkson Potter. ISBN 0-517-59373-4.

- Smith, Joel (1999), Edward Steichen: The Early Years. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Steichen, Joanna (2000), Steichen's Legacy: Photographs, 1895–1973, Alfred A. Knopf, ISBN 978-0-679-45076-4.

- Haskell, Barbara (2000), Edward Steichen (exhibition catalogue). New York: Whitney Museum of American Art.

- Bjerke, Øivind Storm (2002), Edward Steichen: Art as Advertising, Advertising as Art. Works from the Collection of Norsk museum for fotografi - Preus fotomuseum (exhibition catalogue), Norsk museum for fotografi - Preus fotomuseum.

- Cohen DePietro, Anne; Goley, Mary Anne (2003), Eduard Steichen: Four Paintings in Context (exhibition catalogue). Hollis Taggart Galleries.

- Brandow, Todd; Ewing, William A. (2007), Edward Steichen: Lives in Photography (exhibition catalogue), Foundation for the Exhibition of Photography/Musée de l'Elysée/W.W. Norton

- Mitchell, Emily (2007), The Last Summer of the World. Norton. (A fictional narrative about Steichen.)

- Hurm, Gerd; Anke Reitz; Shamoon Zamir, eds. (2017),The Family of Man Revisited: Photography in a Global Age. London and Milton Park: I.B. Tauris and Routledge. ISBN 978-178453967-2.

- Martineau, Paul, ed. (2018), Icons of Style: A Century of Fashion Photography, The J. Paul Getty Museum, ISBN 978-1-60606-558-7.

- Polfer, Michel (2023), Edward Steichen (the 178 prints of the bequest to the National Museum of Luxembourg), Milan: Silvana, ISBN 978-8836651559.

External links

[edit]Collections of his work

[edit]- 173 Works by Edward Steichen at the Museum of Modern Art, New York

- Steichen Collection at the Musée National d'Histoire et d'Art, Luxembourg

- The Family of Man from 1955 permanent installment at Clervaux Castle

- The Bitter Years (Steichen's last curated exhibition at MoMA from 1962) at Waasertuerm Gallery

- The Family of Man on VisitLuxembourg

- Biographical text and 174 works by Steichen at The Art Institute of Chicago

- and a unique album with World War I–era aerial photographs by Steichen)

- also in the Alfred Stieglitz Collection

- Works by Edward Steichen or search resulting in 136 photographs at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (publications on their Alfred Stieglitz Collection with prints and material on Steichen)

- Works by Edward Steichen (with some odd search results), and specifically the Oochens Series (mostly in watercolor) at the National Gallery of Art, Washington

- Edward Steichen at the George Eastman Museum, Rochester (over 2000 photographs; regular works, private snapshots, test takes and contact sheets are undifferentiated and often not dated yet)

- Works by Edward Steichen at the International Center of Photography, New York (about 30 unsorted photographs and additional documents like magazines)

- American Expeditionary Force Photo Section (Steichen) Collection 1917-1919 at Smithsonian, National Air and Space Museum at the Wayback Machine (archived 2020-10-25)

- Edward J. Steichen World War II Navy Photographs Collection, 1941-1945 at Smithsonian, National Air and Space Museum at the Wayback Machine (archived 2020-10-25)

Writings and other documents

[edit]- Edward Steichen Archive (alternative link) at the Museum of Modern Art Archive

- Edward J. Steichen papers at George Eastman Museum Archives (Gift of Joanna Taub Steichen, 2001)

- The Steichen Family Papers at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University

- Mary Steichen Calderone Papers at Schlesinger Library, Harvard University

- Carl Sandburg Home, North Carolina from the National Park Service

- Carl Sandburg Papers at University of Illinois

- Rodin and Steichen at Musee Rodin

Further reading

[edit]- David Joseph (DJ) Marcou: Edward Steichen, HonFRPS: Renaissance Man, RPS Journal, March 2004, pp. 72–75.

- "From Luxembourg and America to the World: Edward Steichen's Photographic Legacy" Archived 2021-02-22 at the Wayback Machine at La Crosse History Unbound

References

[edit]- ^ "Edward Steichen". Art Institute of Chicago. n.d..

- ^ "Edward Steichen". International Center of Photography. 17 May 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Family of Man". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. 2008-05-16. Archived from the original on 2010-02-25. Retrieved 14 December 2009.

- ^ Tooth, Roger (15 February 2006), "At $2.9m, Pond–Moonlight becomes world's most expensive photograph", The Guardian.

- ^ Pogrebin, Robin (9 November 2022). "Paul G. Allen's Art at Christie's Tops $1.5 Billion, Cracking Records". New York Times. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ a b Niven, Penelope (1997), Steichen: A Biography. New York: Clarkson Potter. ISBN 0-517-59373-4, p. 4.

- ^ "Lilian "Paula" Sandburg". National Park Service. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- ^ Niven, Penelope (1997), Steichen: A Biography. New York: Clarkson Potter. ISBN 0-517-59373-4, p. 6.

- ^ Niven, Penelope (1997), Steichen: A Biography. New York: Clarkson Potter. ISBN 0-517-59373-4, p. 16.

- ^ Elçi, Yasemin (October 2020). "From Bivange to Manhattan". Luxembourg Times. No. 6. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Faram, Mark D. (2009), Faces of War: The Untold Story of Edward Steichen's WWII Photographers Penguin. p. 15–16.

- ^ a b Gedrim, Ronald J. (1996), Edward Steichen: Selected Texts and Bibliography. Oxford, UK: Clio Press. ISBN 1-85109-208-0, p. xiii.

- ^ Niven (1997), p. 28.

- ^ Niven (1997), p. 29.

- ^ Niven (1997), p. 42.

- ^ "Edward Steichen". The Art Story. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ Niven (1997), p. 66.

- ^ Niven, Penelope (1997), Steichen: A Biography. New York: Clarkson Potter. ISBN 0-517-59373-4, p. 74.

- ^ Niven (1997), p. 75.

- ^ Roberts, Pam (1997). "Alfred Stieglitz, 291 Gallery and Camera Work," in: Alfred Stieglitz (ed.), Camera Work, The Complete Illustrations 1903–1917. Köln: Taschen. ISBN 3-8228-8072-8, p. 17.

- ^ Mosar, Christian (2007), Bloom! Experiments in Color Photography by Edward Steichen. A Selection from George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film, Luxembourg: MUDAM, ISBN 978-2-919873-02-9.

- ^ Samels, Zoë (29 September 2016). "Edward Steichen". National Gallery of Art. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ Ewing, William A. (2008). Edward Steichen. Penguin Random House. ISBN 978-0-500-41093-6.

- ^ a b c "Series 6 of Edward Steichen Archive in The Museum of Modern Art Archives". MoMA. Retrieved 2019-06-28.

- ^ a b Aubenas, Sylvie; Henri, Jules, and Louis Séeberger; Xavier Demange; Virginie Chardin (2006), Les Séeberger, photographes de l'élégance, 1909-1939 (exhibition catalogue, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Galerie de photographie), Bibliothèque nationale de France / Seuil, ISBN 2020878356

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - ^ a b Niven (1997), p. 352.

- ^ Steichen's prints appeared in an article by Paul Cornu, "L'art de la robe", in Art et Décoration, April 1911, p. 101–118.

- ^ Edward Steichen, Experiment in Three-Color Photography in "Our lllustrations", in Camera Work. No. 15 (July 1906), p. 44.

- ^ Steichen, Joanna T.; Alison Nordstrom; Jessica Johnston (2010), Steichen in Color: Portraits, Fashion & Experiments, New York: Sterling, ISBN 978-1-4027-6000-6

- ^ a b c d Martineau, Paul, ed. (2018), Icons of style: A Century of Fashion Photography, The J. Paul Getty Museum, p. 29, ISBN 978-1-60606-558-7

- ^ Steichen, Edward (1963), A Life in Photography, Allen, p. facing plate 95

- ^ Hardesty, Von (2015). Camera Aloft: Edward Steichen in the Great War. Cambridge University Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-521-82055-4.

- ^ a b Bristol, Horace; Jacobs, Fenno; Jorgensen, Victor; Kerlee, Charles E.; Miller, Wayne F.; Steichen, Edward; Unit (U.S.), Naval Aviation Photographic. "Edward Steichen. An Inventory of His Naval Aviation Photographic Unit Photographs at the Harry Ransom Center". norman.hrc.utexas.edu. Retrieved 2019-06-27.

- ^ An exhibition in Orlando in 2019/20 focused on Steichen's dedication to flowers. Examples especially of his rarely seen paintings are displayed in a review of Edward Steichen: In Exaltation of Flowers by Suzanne Cohen on Art Districts Magazine, n. d. [Sept 2019], and on the museum's website. Accessed 30 August 2024.

- ^ Sandeen, Eric J (1995), Picturing an exhibition: the family of man and 1950s America (1st ed.), University of New Mexico Press, ISBN 978-0-8263-1558-8

- ^ Steichen, Edward; Phillips, Christopher (1981), Steichen at war, H.N. Abrams, ISBN 978-0-8109-1639-5

- ^ Steichen, Edward (1947), The Blue Ghost: a photographic log and personal narrative of the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Lexington in combat operation (1st ed.), Harcourt, Brace

- ^ Budiansky, Stephen, "The Photographer who Took the Navy's Portrait", World War II, Volume 26, No. 2, July/August 2011, p. 25

- ^ Faram, Mark D (2009), Faces of war: the untold story of Edward Steichen's WWII photographers (1st ed.), Berkley Caliber, ISBN 978-0-425-22140-2

- ^ "Museum of Modern Art Press Release: Museum of Modern Art exhibits official photographs of Naval Sea and Air Action in the Pacific" (PDF).

- ^ "Museum of Modern Art press release–'Edward Steichen appointed Head of Photography at Museum of Modern Art'" (PDF). July 15, 1947.

- ^ Hill, Jason; Schwartz, Vanessa R; ebrary, Inc (2015), Getting the picture: the visual culture of the news, Bloomsbury Academic, ISBN 978-1-4725-6664-5

- ^ Stegner, Wallace (2017), Alinder, Mary Street; Stillman, Andrea G (eds.), Ansel Adams: Letters, 1916–1984, New York: Little, Brown and Co., p. ?, ISBN 978-0-316-43699-1

- ^ Street Alinder, Mary (1996), Ansel Adams: a Biography. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 0-8050-5835-4, p. 192.

- ^ Alinder (1996), p. 193.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Warren, Lynne (2005), Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century Photography (3 Volumes), Taylor & Francis, p. 1106, ISBN 978-0-203-94338-0.

- ^ Steichen, Edward, ed. (1962), The Bitter Years: 1935–1941. Rural America as Seen by the Photographers of the Farm Security Administration (PDF), Museum of Modern Art)

- ^ Dickie, Chris (2009), Photography: the 50 most influential photographers in the world, A & C Black, p. 117, ISBN 978-1-4081-0944-1

- ^ a b Steichen, Edward; Sandburg, Carl (1955). The family of man: the photographic exhibition. Simon and Schuster.

- ^ "Work of Three Young Photographers Exhibited by The Museum of Modern Art". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "In and Out of Focus". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Exhibition of 50 Photographs by 50 Photographers – Landmarks in Photographic History". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Photo-Secession (American Photography 1902–1910)". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Photographs by Lisette Model, Bill Brandt, Ted Croner and Harry Callahan". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "This Exact Instant, Events and Pages in 100 Years of News Photography". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Roots of Photography". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Four Phases in Present Day Photography Shown in Museum Exhibition". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Photographs by Margaret Bourke-White, Helen Levitt, Dorothea Lange, Tana Hoban, Esther Bubley and Hazel Frieda Larsen". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Roots of French Photography". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Photographs of Picasso by Gjon Mili and by Robert Capa". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Photography Recent Acquisitions: Stieglitz, Atget". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Color Photography". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Photographs by 51 Photographers". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Photographs by Lewis Carroll". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Korea – The Impact of War in Photographs". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Abstraction in Photography". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "12 Photographers". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Forgotten Photographers". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Memorable Life Photographs". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Christmas Photographs". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Five French Photographers". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Diogenes with a Camera". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Then and Now". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Diogenes with a Camera". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Always the Young Strangers". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Postwar European Photography". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "The Family of Man". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ "Diogenes with a Camera III". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ "Diogenes with a Camera IV". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ "Language of the Wall: Parisian Graffiti Photographed by Brassaï". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ "70 Photographers Look at New York". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ "Photographs from the Museum Collection". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ "Photographs for Collectors". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ "Harry Callahan and Robert Frank". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ "The Bitter Years: 1935–1941". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ "Press release for The Sense of Abstraction" (PDF). The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ "The Sense of Abstraction". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ "50 Photographs by 50 Photographers". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ "Press release for The Sense of Abstraction" (PDF). The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ "Artist Info".

- ^ United States. (1967). Copyright law revision: Hearings before the Subcommittee on Patents, Trademarks, and Copyrights of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, Ninetieth Congress, first session pursuant to S. Res. 37 on S. 597., U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ "Grace M. Mayer Papers in The Museum of Modern Art". www.moma.org. Retrieved 2019-06-28.

- ^ Niven (1997), p. 530.

- ^ Niven (1997), p. 698.

- ^ Prevost, Lisa, "An Upscale Town with Upcountry Style,"New York Times, 3 January 1999.

- ^ Town of Redding. "Town of Redding – Topstone Park". Townofreddingct.org. Retrieved 2019-02-10.

- ^ Besson, George (October 1908). "Pictorial Photography: A Series of Interviews". Camera Work. 24: 14.

- ^ "World | Americas | Rare photo sets $2.9m sale record". BBC News. February 15, 2006. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ^ "Musée d'Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean, Luxembourg, v3.0". Mudam.lu. Archived from the original on March 26, 2019. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ^ "Artist's wife sues for loss of his love; Mrs. Eduard Steichen says Marion Beckett alienated her husband's affections. Asks for $200,000 damages; declares other woman followed the painter to Paris, where he was honored by France". The New York Times. July 5, 1919. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ Mitchell, Emily (2007). The last summer of the world. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-06487-2. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ Grimes, William (7 August 2010). "Joanna Steichen obituary". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Auer, Michèle; Auer, Michel (1985), Encyclopédie internationale des photographes de 1839 à nos jours = Photographers Encyclopaedia International 1839 to the Present, Editions Camera obscura, ISBN 978-2-903671-06-8.

- ^ Lewis, Jo Ann (November 26, 2000). "Edward Steichen, Examined Through an Unflattering Lens". Washington Post. Retrieved 2019-06-29.

- ^ J. Steichen 2000, p. 371.

- ^ "Exhibition Hollywood Celebrities - artist, news & exhibitions - photography-now.com". photography-now.com.

- ^ "Exhibition Hollywood Celebrity: Edward Steichen's Vanity Fair Portraits - artist, news & exhibitions - photography-now.com". photography-now.com. Retrieved 2019-06-29.

- ^ Lewis, Jo Ann (November 26, 2000). "Edward Steichen, Examined Through an Unflattering Lens". Washington Post. Retrieved 2019-06-29.

- ^ Kramer, Hilton (November 20, 2000). "Steichen's Sappy Photos Not Redeemed at Whitney". Observer. Retrieved 2019-06-29.

- ^ "Edward Steichen Exhibition: 22 Apr–21 May 2005 Luxemburgische Botschaft". photography-now.com. Retrieved 2019-06-29.

- ^ "Edward Steichen, Une Epopée Photographique". Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia. Retrieved 2024-09-01.

- ^ Brandow, Todd; Ewing, William A. (2007), Edward Steichen: Lives in Photography (exhibition catalogue), Foundation for the Exhibition of Photography/Musée de l'Elysée/W.W. Norton

- ^ "Exhibition Steichen, une épopée photographique - artist, news & exhibitions - photography-now.com". photography-now.com. Retrieved 2019-06-29.

- ^ "Edward Steichen: Lives in Photography / Une épopée photographique". photography-now.com. Retrieved 2024-09-01.

- ^ "Edward Steichen, Une Epopée Photographique". Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia. Retrieved 2024-09-01.

- ^ "Edward Steichen". Palazzomagnani.it. Retrieved 2024-08-29.

- ^ Edward Steichen in High Fashion. The Condé Nast Years 1923–1937 at the museum's website. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ Exhibition Edward Steichen on the museum's website. Retrieved 2 September 2024.

- ^ "Exhibition Edward Steichen - artist, news & exhibitions - photography-now.com". photography-now.com. Retrieved 2019-06-29.

- ^ Edward Steichen: In Exaltation of Flowers on the website of Orlando Museum of Art. Review by Suzanne Cohen on Art Districts Magazine, n. d. [Sep 2024]. Accessed 30 August 2024.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch