2011 Egyptian revolution

| 2011 Egyptian revolution | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ثورة ٢٥ يناير (Arabic) Part of the Egyptian Crisis, the Arab Spring, and the Iran–Saudi Arabia proxy conflict | |||

Demonstrators in Cairo's Tahrir Square on 8 February 2011 | |||

| Date | 25 January 2011 – 11 February 2011 (2 weeks and 3 days) | ||

| Location | 30°2′40″N 31°14′8″E / 30.04444°N 31.23556°E | ||

| Caused by | |||

| Goals |

| ||

| Methods | |||

| Resulted in |

| ||

| Parties | |||

| Lead figures | |||

| Number | |||

| 2,000,000 at Cairo's Tahrir Square See: Regions section below. | |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) |

| ||

| Injuries | 6,467 people[18] | ||

| Arrested | 12,000[19] | ||

| Part of a series on the Egyptian Crisis (2011–2014) |

|---|

|

| |

The 2011 Egyptian revolution, also known as the 25 January Revolution (Arabic: ثورة ٢٥ يناير, romanized: Thawrat khamsa wa-ʿišrūn yanāyir;),[20] began on 25 January 2011 and spread across Egypt. The date was set by various youth groups to coincide with the annual Egyptian "Police holiday" as a statement against increasing police brutality during the last few years of Hosni Mubarak's presidency. It consisted of demonstrations, marches, occupations of plazas, non-violent civil resistance, acts of civil disobedience and strikes. Millions of protesters from a range of socio-economic and religious backgrounds demanded the overthrow of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak. Violent clashes between security forces and protesters resulted in at least 846 people killed and over 6,000 injured.[21][22] Protesters retaliated by burning over 90 police stations across the country.[23]

The Egyptian protesters' grievances focused on legal and political issues,[24] including police brutality, state-of-emergency laws,[1] lack of political freedom, civil liberty, freedom of speech, corruption,[2] high unemployment, food-price inflation[3] and low wages.[1][3] The protesters' primary demands were the end of the Mubarak regime. Strikes by labour unions added to the pressure on government officials.[25] During the uprising, the capital, Cairo, was described as "a war zone"[26] and the port city of Suez saw frequent violent clashes. Protesters defied a government-imposed curfew, which the police and military could not enforce in any case. Egypt's Central Security Forces, loyal to Mubarak, were gradually replaced by military troops. In the chaos, there was looting by rioters which was instigated (according to opposition sources) by plainclothes police officers. In response, watch groups were organised by civilian vigilantes to protect their neighborhoods.[27][28][29][30][31]

On 11 February 2011, Vice President Omar Suleiman announced that Mubarak resigned as president, turning power over to the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF).[32] The military junta, headed by effective head of state Muhammad Tantawi, announced on 13 February that the constitution is suspended, both houses of parliament dissolved and the military would govern for six months (until elections could be held). The previous cabinet, including Prime Minister Ahmed Shafik, would serve as a caretaker government until a new one was formed.[33]

After the revolution against Mubarak and a period of rule by the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, the Muslim Brotherhood took power in Egypt through a series of popular elections, with Egyptians electing Islamist Mohamed Morsi to the presidency in June 2012, after winning the election over Ahmed Shafik.[34] However, the Morsi government encountered fierce opposition after his attempt to pass an Islamic-leaning constitution. Morsi also issued a temporary presidential decree that raised his decisions over judicial review to enable the passing of the constitution.[35] It sparked general outrage from secularists and members of the military, and a revolution broke out against his rule on 28 June 2013.[36] On 3 July 2013, Morsi was deposed following the army's intervention on the side of the revolution. The move was led by the minister of defence, General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi,[37] as millions of Egyptians took to the streets in support of early elections.[38] Sisi went on to become Egypt's president after an election in 2014 which was boycotted by opposition parties.[39]

Other names

[edit]In Egypt and other parts of the Arab world, the protests and governmental changes are also known as the 25 January Revolution (ثورة 25 يناير Thawrat 25 Yanāyir), Revolution of Freedom (ثورة حرية Thawrat Horeya)[40] or Revolution of Rage (ثورة الغضب Thawrat al-Ġaḍab), and, less frequently,[41] the Youth Revolution (ثورة الشباب Thawrat al-Shabāb), Lotus Revolution[42] (ثورة اللوتس) or White Revolution (الثورة البيضاء al-Thawrah al-bayḍāʾ).[43]

Background

[edit]

Hosni Mubarak became President of Egypt after the assassination of Anwar Sadat in 1981. He inherited an authoritarian system from Sadat which was imposed in 1952 following the coup against King Farouk. The coup in 1952 led to the abolishment of the monarchy and Egypt became a one party and military dominated state. Nasser who was a member of the Free Officers became the second President of Egypt following the resignation of Muhammad Naguib and under his rule, the Arab Socialist Union operated as the sole political party in Egypt. Under Sadat, the multi-party system during the monarchy was reintroduced but the National Democratic Party (which evolved from Nasser’s Arab Socialist Union) remained dominant in Egypt’s politics and there were restrictions on opposition parties. Mubarak's National Democratic Party (NDP) maintained one-party rule.[44] His government received support from the West and aid from the United States by its suppression of Islamic militants and maintaining the peace treaty with Israel.[44] Mubarak was often compared to an Egyptian pharaoh by the media and some critics, due to his authoritarian rule.[45] He was in the 30th year of his regime when the 2011 uprising began.[46]

Most causes of the revolution against Mubarak—inherited power, corruption, under-development, unemployment, unfair distribution of wealth and the presence of Israel—also existed in 1952, when the Free Officers ousted King Farouk.[47] A new cause of the 2011 revolution was the increase in population, which aggravated unemployment.[48]

During his presidency, Anwar Sadat neglected the modernisation of Egypt in contrast to his predecessor, Gamal Abdel Nasser, and his cronyism cost the country infrastructure industries which could generate new jobs. Communications media such as the internet, cell phones and satellite TV channels augmented mosques and Friday prayers, traditional means of mass communications. The mosques brought the Muslim Brotherhood to power, and the Brotherhood pressured all governments from 1928 through 2011 (as it had also done in neighbouring countries).[48]

Inheritance of power

[edit]

Mubarak's younger son, Gamal Mubarak, was rumoured in 2000 to succeed his father as the next president of Egypt.[49] Gamal began receiving attention from the Egyptian media, since there were apparently no other heirs to the presidency.[50] Bashar al-Assad's rise to power in Syria in June 2000, after the death of his father Hafez, sparked debate in the Egyptian press about the prospects for a similar scenario in Cairo.[51]

During the years after Mubarak's 2005 re-election, several left- and right-wing (primarily unofficial) political groups expressed opposition to the inheritance of power, demanded reforms and asked for a multi-candidate election. In 2006, with opposition increasing, Daily News Egypt reported an online campaign initiative (the National Initiative against Power Inheritance) demanding that Gamal reduce his power. The campaign said, "President Mubarak and his son constantly denied even the possibility of [succession]. However, in reality they did the opposite, including amending the constitution to make sure that Gamal will be the only unchallenged candidate."[52]

During the decade, public perception grew that Gamal would succeed his father. He wielded increasing power as NDP deputy secretary general and chair of the party's policy committee. Analysts described Mubarak's last decade in power as "the age of Gamal Mubarak". With his father's health declining and no appointed vice-president, Gamal was considered Egypt's de facto president by some.[53] Although Gamal and his father denied an inheritance of power, he was speculated as likely to be chosen as the NDP candidate in the presidential election scheduled for 2011, when Hosni Mubarak's presidential term was set to expire.[54] Gamal ultimately declined to run following the 2011 protests.[55]

State-of-emergency law

[edit]Egypt was under a state of emergency since the assassination of Sadat in 1981, pursuant to Law No. 162 of 1958. A previous state of emergency was enacted in the 1967 Six-Day War before being lifted in 1980.[56][57] Police powers were extended, constitutional rights and habeas corpus were effectively suspended and censorship was legalised as a result.[58] The emergency law limited non-governmental political activity, including demonstrations, unapproved political organisations and unregistered financial donations.[56] The Mubarak government cited the threat of terrorism in extending the state of emergency,[57] claiming that opposition groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood could gain power in Egypt if the government did not forge parliamentary elections and suppress the group through emergency law.[59] This led to the imprisonment of activists without trial,[60] illegal, undocumented and hidden detention facilities[61] and the rejection of university, mosque and newspaper staff based on their political affiliation.[62] A December 2010 parliamentary election was preceded by a media crackdown, arrests, candidate bans (particularly Muslim Brotherhood candidates) and allegations of fraud due to the near-unanimous victory by the NDP in parliament.[56] Human rights organizations estimated that in 2010, between 5,000 and 10,000 people were in long-term detention without charge or trial.[63][64]

Police brutality

[edit]According to a US Embassy report, police brutality had been widespread in Egypt.[65] In the five years before the revolution, the Mubarak regime denied the existence of torture or abuse by police. However, claims by domestic and international groups provided cellphone videos or first-hand accounts of hundreds of cases of police brutality.[66] According to the 2009 Human Rights Report from the US State Department, "Domestic and international human rights groups reported that the Ministry of Interior (MOI) State Security Investigative Service (SSIS), police, and other government entities continued to employ torture to extract information or force confessions. The Egyptian Organization for Human Rights documented 30 cases of torture during the year 2009. In numerous trials defendants alleged that police tortured them during questioning. During the year activists and observers circulated some amateur cellphone videos documenting the alleged abuse of citizens by security officials. For example, on 8 February, a blogger posted a video of two police officers, identified by their first names and last initials, sodomizing a bound naked man named Ahmed Abdel Fattah Ali with a bottle. On 12 August, the same blogger posted two videos of alleged police torture of a man in a Port Said police station by the head of investigations, Mohammed Abu Ghazala. There was no indication that the government investigated either case."[67]

The deployment of Baltageya (Arabic: بلطجية)—plainclothes police—by the NDP was a hallmark of the Mubarak government.[68] The Egyptian Organisation for Human Rights documented 567 cases of torture, including 167 deaths, by police from 1993 to 2007.[69] Excessive force was often used by law enforcement agencies against popular uprisings.[70]

On 6 June 2010, a twenty-eight-year-old Egyptian, Khaled Mohamed Saeed, died under disputed circumstances in the Sidi Gaber area of Alexandria, with witnesses testifying that he was beaten to death by police – an event which galvanised Egyptians around the issue of police brutality.[71][72][73] Authorities stated that Khaled died choking on hashish while being chased by police officers. Pictures which were released of Khaled's disfigured corpse from the morgue showed signs of torture.[74] A Facebook page, "We are all Khaled Said", helped attract nationwide attention to the case.[75] Mohamed ElBaradei, former head of the International Atomic Energy Agency, led a 2010 rally in Alexandria against police abuse, and visited Saeed's family to offer condolences.[76]

During the January–February 2011 protests, police brutality was common. Jack Shenker, a reporter for The Guardian, was arrested during the Cairo protests on 26 January. He witnessed fellow Egyptian protesters being tortured, assaulted, and taken to undisclosed locations by police officers. Shenker and other detainees were released after covert intervention by Ayman Nour, the father of a fellow detainee.[77][78][79]

Election corruption

[edit]Corruption, coercion not to vote and manipulation of election results occurred during many elections over Mubarak's 30-year rule.[80] Until 2005, Mubarak was the only presidential candidate (with a yes-or-no vote).[81] Mubarak won five consecutive presidential elections with a sweeping majority. Although opposition groups and international election-monitoring agencies charged that the elections were rigged, those agencies were not allowed to monitor elections. The only opposition presidential candidate in recent Egyptian history, Ayman Nour, was imprisoned before the 2005 elections.[82] According to a 2007 UN survey, voter turnout was extremely low (about 25 per cent) because of a lack of trust in the political system.[81]

Demographic and economic challenges

[edit]Unemployment and reliance on subsidised goods

[edit]

The population of Egypt grew from 30,083,419 in 1966[83] to roughly 79,000,000 by 2008.[84] The vast majority of Egyptians live near the banks of the Nile, in an area of about 40,000 square kilometers (15,000 sq mi) where the only arable land is found. In late 2010, about 40 per cent of Egypt's population lived on the equivalent of roughly US$2 per day, with a large portion relying on subsidised goods.[1]

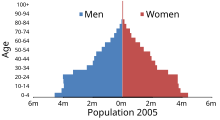

According to the Peterson Institute for International Economics and other proponents of demographic structural approach (cliodynamics), a basic problem in Egypt is unemployment driven by a demographic youth bulge; with the number of new people entering the workforce at about four per cent a year, unemployment in Egypt is almost 10 times as high for college graduates as for those who finished elementary school (particularly educated urban youth—the people who were in the streets during the revolution).[85][86]

Economy and poor living conditions

[edit]Egypt's economy was highly centralised during the presidency of Gamal Abdel Nasser, becoming more market-driven under Anwar Sadat and Mubarak. From 2004 to 2008 the Mubarak government pursued economic reform to attract foreign investment and increase GDP, later postponing further reforms because of the Great Recession. The international economic downturn slowed Egypt's GDP growth to 4.5 per cent in 2009. In 2010, analysts said that the government of Prime Minister Ahmed Nazif would need to resume economic reform to attract foreign investment, increase growth and improve economic conditions. Despite recent high national economic growth, living conditions for the average Egyptian remained relatively poor[87] (albeit better than other African nations[85] with no significant social upheavals).

Corruption

[edit]Political corruption in the Mubarak administration's Interior Ministry rose dramatically, due to increased control of the system necessary to sustain his presidency.[88] The rise to power of powerful businessmen in the NDP, the government and the House of Representatives led to public anger during the Ahmed Nazif government. Ahmed Ezz monopolised the steel industry, with more than 60 per cent of market share.[89] Aladdin Elaasar, an Egyptian biographer and American professor, estimated that the Mubarak family was worth from $50 to $70 billion.[90][91]

The wealth of former NDP secretary Ezz was estimated at E£18 billion;[92] the wealth of former housing minister Ahmed al-Maghraby was estimated at more than E£11 billion;[92] that of former tourism minister Zuhair Garrana is estimated at E£13 billion;[92] former minister of trade and industry Rashid Mohamed Rashid is estimated to be worth E£12 billion,[92] and former interior minister Habib al-Adly was estimated to be worth E£8 billion.[92] The perception among Egyptians was that the only people benefiting from the nation's wealth were businessmen with ties to the National Democratic Party: "Wealth fuels political power and political power buys wealth."[93]

During the 2010 elections, opposition groups complained about government harassment and fraud. Opposition and citizen activists called for changes to a number of legal and constitutional provisions affecting elections.[94] In 2010, Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) gave Egypt a score of 3.1 based on perceptions by business people and analysts of the degree of corruption (with 10 being clean, and 0 totally corrupt).[95]

Prelude

[edit]To prepare for the possible overthrow of Mubarak, opposition groups studied Gene Sharp's work on nonviolent action and worked with leaders of Otpor, the student-led Serbian organisation. Copies of Sharp's list of 198 non-violent "weapons", translated into Arabic and not always attributed to him, were circulated in Tahrir Square during its occupation.[96][97]

Tunisian revolution

[edit]Following the ousting of Tunisian president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali after mass protests, many analysts (including former European Commission President Romano Prodi) saw Egypt as the next country where such a revolution might occur.[98] According to The Washington Post, "The Jasmine Revolution [...] should serve as a stark warning to Arab leaders – beginning with Egypt's 83-year-old Hosni Mubarak – that their refusal to allow more economic and political opportunity is dangerous and untenable."[99] Others believed that Egypt was not ready for revolution, citing little aspiration by the Egyptian people, low educational levels and a strong government with military support.[100] The BBC said, "The simple fact is that most Egyptians do not see any way that they can change their country or their lives through political action, be it voting, activism, or going out on the streets to demonstrate."[101]

Self-immolation

[edit]

After the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi in Tunisia on 17 December, a man set himself on fire on 18 January in front of the Egyptian parliament[102] and five more attempts followed.[100] On 17 January, Abdou Abdel Monaam, a baker, also set himself on fire to protest a law that prevented restaurant owners from buying subsidised bread, leading him to buy bread at the regular price – which is five times higher than the subsidised. Mohammed Farouq Mohammed, who is a lawyer, also set himself alight in front of the parliament to protest his ex-wife, who did not allow him to see his daughters.[103] In Alexandria, an unemployed man by the name of Ahmed Hashem Sayed also set himself on fire.[104]

National Police Day protests

[edit]Opposition groups planned a day of revolt for 25 January, coinciding with National Police Day, to protest police brutality in front of the Ministry of Interior.[105] Protesters also demanded the resignation of the Minister of Interior, an end to State corruption, the end of emergency law and presidential term limits for the president.

Many political movements, opposition parties and public figures supported the day of revolt, including Youth for Justice and Freedom, the Coalition of the Youth of the Revolution, the Popular Democratic Movement for Change, the Revolutionary Socialists and the National Association for Change. The April 6 Youth Movement was a major supporter of the protest, distributing 20,000 leaflets saying "I will protest on 25 January for my rights". The Ghad El-Thawra Party, Karama, Wafd and Democratic Front supported the protests. The Muslim Brotherhood, Egypt's largest opposition group,[106] confirmed on 23 January that it would participate.[107] Public figures, including novelist Alaa Al Aswany, writer Belal Fadl and actors Amr Waked and Khaled Aboul Naga, announced that they would participate. The leftist National Progressive Unionist Party (the Tagammu) said that it would not participate, and the Coptic Church urged Christians not to participate in the protests.[106]

Twenty-six-year-old Asmaa Mahfouz was instrumental[108] in sparking the protests.[109][110] In a video blog posted a week before National Police Day,[111] she urged the Egyptian people to join her on 25 January in Tahrir Square to bring down the Mubarak regime.[112] Mahfouz's use of video blogging and social media went viral[113] and urged people not to be afraid.[114] The Facebook group for the event attracted 80,000 people.

Timeline

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2011) |

25 January 2011 ("Day of Revolt"): Protests erupted throughout Egypt, with tens of thousands gathering in Cairo and thousands more in other Egyptian cities. The protests targeted the Mubarak government; while mostly non-violent, there were some reports of civilian and police casualties.

26 January 2011: Civil unrest in Suez and other areas throughout the country. Police arrested many activists.

27 January 2011: The government shuts down four major ISPs at approximately 5:20 p.m. EST.[115] disrupting Internet traffic and telephone services[116]

28 January 2011: The "Friday of Anger" protests began, with hundreds of thousands demonstrating in Cairo and other Egyptian cities after Friday prayers. Opposition leader Mohamed El Baradei arrived in Cairo amid reports of looting. Prisons were opened and burned down, allegedly on orders from Interior Minister Habib El Adly. Prison inmates escaped en masse, in what was believed to be an attempt to terrorise protesters. Police were withdrawn from the streets, and the military was deployed. International fears of violence grew, but no major casualties were reported. Mubarak made his first address to the nation, pledging to form a new government. Later that night clashes broke out in Tahrir Square between revolutionaries and pro-Mubarak demonstrators, leading to casualties. No fatalities have been reported in Cairo, however, 11 people were killed in Suez and another 170 were injured.1,030 people were reported injured nationwide.

29 January 2011: The military presence in Cairo increased. A curfew was imposed, which was widely ignored as the flow of protesters into Tahrir Square continued through the night. The military reportedly refused to follow orders to fire live ammunition, exercising overall restraint; there were no reports of major casualties. On 31 January, Israeli media reported that the 9th, 2nd, and 7th Divisions of the Egyptian Army had been ordered into Cairo to help restore order.[117]

1 February 2011: Mubarak made another televised address, offering several concessions. He pledged political reforms and said he would not run in the elections planned for September, but would remain in office to oversee a peaceful transition. Small but violent clashes began that night between pro- and anti-Mubarak groups.

2 February 2011 (Camel Incident): Violence escalated as waves of Mubarak supporters met anti-government protesters; some Mubarak supporters rode camels and horses into Tahrir Square, reportedly wielding sticks. The attack resulted in 3 deaths and 600 injuries.[118] Mubarak repeated his refusal to resign in interviews with several news agencies. Violence toward journalists and reporters escalated, amid speculation that it was encouraged by Mubarak to bring the protests to an end. The camel and horse riders later claimed that they were "good men", and they opposed the protests because they wanted tourists to come back to keep their jobs and feed their animals. The horse and camel riders deny that they were paid by anyone, though they said that they were told about the protests from a ruling party MP. Three hundred people were reported dead by the Human Rights Watch the following day, since 25 January.[119][120] Wael Ghonim, Google executive and creator of the page We are all Khaled Said, was reported missing and the company asked the public to help find him.[121]

6 February 2011: An interfaith service was held with Egyptian Christians and Muslims in Tahrir Square. Negotiations by Egyptian Vice President Omar Suleiman and opposition representatives began during continuing protests throughout the country. The Egyptian army assumed greater security responsibilities, maintaining order and guarding The Egyptian Museum of Antiquity. Suleiman offered reforms, while others in Mubarak's regime accused foreign nations (including the US) of interfering in Egypt's affairs.

10 February 2011: Mubarak addressed the Egyptian people amid speculation of a military coup. Instead of resigning (which was widely expected), he said he would delegate some powers to Vice President Suleiman while remaining Egypt's head of state. Mubarak's statement was met with anger, frustration and disappointment, and in a number of cities there was an escalation in the number and intensity of demonstrations.

11 February 2011 ("Friday of Departure"): Large protests continued in many cities, as Egyptians refused to accept Mubarak's concessions. At 6:00 pm Suleiman announced Mubarak's resignation, entrusting the Supreme Council of Egyptian Armed Forces with the leadership of the country.

Post-revolution timeline

[edit]Under the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces

[edit]13 February 2011: The Supreme Council dissolved Egypt's parliament and suspended the constitution in response to demands by demonstrators. The council declared that it would wield power for six months, or until elections could be held. Calls were made for the council to provide details and more-specific timetables and deadlines. Major protests subsided, but did not end. In a gesture to a new beginning, protesters cleaned up and renovated Tahrir Square (the epicentre of the demonstrations), but many pledged to continue protesting until all demands had been met.

17 February: The army said that it would not field a candidate in the upcoming presidential elections.[122] Four important figures in the former regime were arrested that day: former interior minister Habib el-Adly, former minister of housing Ahmed Maghrabi, former tourism minister H.E. Zuheir Garana and steel tycoon Ahmed Ezz.[123]

2 March: The constitutional referendum was tentatively scheduled for 19 March 2011.[124]

3 March: A day before large protests against him were planned, Ahmed Shafik stepped down as prime minister and was replaced by Essam Sharaf.[125]

5 March: Several State Security Intelligence (SSI) buildings across Egypt were raided by protesters, including the headquarters for the Alexandria Governorate and the national headquarters in Nasr City, Cairo. Protesters said that they raided the buildings to secure documents they believed prove crimes by the SSI against the people of Egypt during Mubarak's rule.[126][127]

6 March: From the Nasr City headquarters, protesters acquired evidence of mass surveillance and vote-rigging, noting rooms full of videotapes, piles of shredded and burned documents and cells in which activists recounted their experiences of detention and torture.[128]

19 March: The constitutional referendum passed with 77.27 per cent of the vote.[129]

22 March: Portions of the Interior Ministry building caught fire during police demonstrations outside.[130]

23 March: The Egyptian Cabinet ordered a law criminalising protests and strikes which hamper work at private or public establishments. Under the new law, anyone organising such protests will be subject to imprisonment or a fine of E£500,000 (about US$100,000).[131]

1 April ("Save the Revolution Day"): About 4,000 demonstrators filled Tahrir Square for the largest protest in weeks, demanding that the ruling military council more quickly dismantle lingering aspects of the old regime;[132] protestors also demanded trials for Hosni Mubarak, Gamal Mubarak, Ahmad Fathi Sorour, Safwat El-Sherif and Zakaria Azmi.

8 April ("Cleansing Friday"): Tens of thousands of demonstrators again filled Tahrir Square, criticizing the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces for not following through on their demands: the resignation of remaining regime figures and the removal of Egypt's public prosecutor, due to the slow pace of investigations of corrupt former officials.[133]

7 May: The Imbaba church attacks, in which Salafi Muslims attacked Coptic Christian churches in the working-class neighborhood of Imbaba in Cairo.[134]

27 May ("Second Friday of Anger", "Second Revolution of Anger" or "The Second Revolution"): Tens of thousands of demonstrators filled Tahrir Square,[135] in addition to demonstrations in Alexandria, Suez, Ismailia and Gharbeya, in the largest demonstrations since the ouster of the Mubarak regime. Protestors demanded no military trials for civilians, restoration of the Egyptian Constitution before parliament elections and for all members of the old regime (and those who killed protesters in January and February) to stand trial.

1 July ("Friday of Retribution"): Thousands of protesters gathered in Suez, Alexandria and Tahrir Square to voice frustration with the ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces for what they called the slow pace of change, five months after the revolution, some also feared that the military was to rule Egypt indefinitely.[136]

8 July ("Friday of Determination"): Hundreds of thousands of protesters gathered in Suez, Alexandria and Tahrir Square, demanding immediate reform and swifter prosecution of former officials from the ousted government.[137]

15 July: Tahrir Square protests continued.

23 July: Thousands of protesters attempted to march to the defence ministry after a speech by Muhammad Tantawi commemorating the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, but are met with counter-insurgents with sticks, stones and Molotov cocktails.

1 August: Egyptian soldiers clashed with protesters, tearing down tents. Over 80 people were arrested.[138]

6 August: Hundreds of protesters gathered and prayed in Tahrir Square before they were attacked by soldiers.[139]

9 September (2011 Israeli embassy attack; the "Friday of Correcting the Path"): Tens of thousands of people protested in Suez, Alexandria and Cairo; however, Islamist protesters were absent.

9 October (Maspero demonstrations):[140][141] Late in the evening of 9 October, during a protest in the Maspiro television building,[142] peaceful Egyptian protesters calling for the dissolution the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, the resignation of Chairman Field Marshal Muhammad Tantawi and the dismissal of the governor of Aswan province were attacked by military police. At least 25 people[143] were killed, and more than 200 wounded.

19 November: Clashes erupted as demonstrators reoccupied Tahrir Square. Central Security Forces used tear gas to control the situation.[144]

20 November: Police attempted to forcibly clear the square, but protesters returned in more than double their original numbers. Fighting continued through the night, with police using tear gas, beating and shooting demonstrators.[144]

21 November: Demonstrators returned to the square, with Coptic Christians standing guard as Muslims protesting the regime pause for prayers. The Health Ministry said that at least 23 died and over 1,500 were injured since 19 November.[144] Solidarity protests were held in Alexandria and Suez.[145] Dissident journalist Hossam el-Hamalawy told Al Jazeera that Egyptians would begin a general strike because they "had enough" of the SCAF.[146]

28 November 2011 – 11 January 2012: Parliamentary elections

17 December 2011: The Institute d'Egypte caught fire during clashes between protesters and Egyptian military; thousands of rare documents burned.[147]

23 January 2012: Democratically elected representatives of the People's Assembly met for the first time since Egypt's revolution, and the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces gave them legislative authority.[148][149][150]

24 January: Field Marshal Tantawi said that the decades-old state of emergency would be partially lifted the following day.[151][152][153][154]

12 April: An administrative court suspended the 100-member constitutional assembly tasked with drafting a new Egyptian constitution.[155][156][157]

23–24 May: First round of voting in the first presidential election since Hosni Mubarak was deposed.

31 May: The decades-long state of emergency expired.[158][159]

2 June: Mubarak and his former interior minister Habib al-Adli were sentenced to life in prison because of their failure to stop the killing during the first six days of the revolution. The former president, his two sons and a business tycoon were acquitted of corruption charges because the statute of limitations had expired. Six senior police officials were also acquitted for their role in the killing of demonstrators, due to lack of evidence.[160][161][162][163]

8 June: Political factions tentatively agreed to a deal to form a new constitutional assembly, consisting of 100 members who will draft the new constitution.[164]

12 June: When the Egyptian parliament met to vote for members of a constitutional assembly dozens of secular MPs walked out, accusing Islamist parties of trying to dominate the panel.[165]

13 June: After Egypt's military government imposed de facto martial law (extending the arrest powers of security forces), the Justice Ministry issued a decree giving military officers authority to arrest civilians and try them in military courts.[166][167][168][169] The provision remains in effect until a new constitution is introduced, and could mean those detained could remain in jail for that long according to state-run Egy News.[170]

14 June: The Egyptian Supreme Constitutional Court ruled that a law passed by Parliament in May, banning former regime figures from running for office, was unconstitutional; this ended a threat to Ahmed Shafik's candidacy for president during Egypt's 2012 presidential election. The court ruled that all articles making up the law regulating the 2011 parliamentary elections were invalid, upholding a lower-court ruling which found that candidates running on party slates were allowed to contest the one-third of parliamentary seats reserved for independents. The Egyptian parliament was dissolved, and the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces resumed legislative authority. The SCAF said that it would announce a 100-person assembly to write the country's new constitution.[170][171][172][173][174]

15 June: Security forces were stationed around Parliament to bar anyone, including lawmakers, from entering the chambers without official authorisation.[175][176]

16–17 June: Second round of voting in the Egyptian presidential election. The SCAF issued an interim constitution,[177][178][179][180][181][182][183][184] giving itself the power to control the prime minister, legislation, the national budget and declarations of war without oversight, and chose a 100-member panel to draft a permanent constitution.[176][185] Presidential powers include the power to choose his vice president and cabinet, to propose the state budget and laws and to issue pardons.[180] The interim constitution removed the military and the defence minister from presidential authority and oversight.[168][180] According to the interim constitution, a permanent constitution must be written within three months and be subject to a referendum 15 days later. When a permanent constitution is approved, a parliamentary election will be held within a month to replace the dissolved parliament.[178][179][180][181]

18 June: The SCAF said that it picked a 100-member panel to draft a permanent constitution[176] if a court strikes down the parliament-picked assembly, planning a celebration at the end of June to mark the transfer of power to the new president.[168][186] Muslim Brotherhood candidate Mohamed Morsi declared himself the winner of the presidential election.[178][179]

19–24 June: Crowds gathered in Tahrir Square to protest the SCAF's dissolution of an elected, Islamist parliament and await the outcome of the presidential election.[187][188][189][190][191][192][193]

24 June: Muslim Brotherhood candidate Mohamed Morsi, the first Islamist elected head of an Arab state, is declared the winner of the presidential election by the Egyptian electoral commission.[194][195][196][197][198][199]

26 June: The Supreme Administrative Court revoked Decree No. 4991/2012 from the Minister of Justice, which granted military intelligence and police the power to arrest civilians (a right previously reserved for civilian police officers).[185][200][201][202]

27–28 June: After the first Constituent Assembly of Egypt was declared unconstitutional and dissolved in April by Egypt's Supreme Administrative Court, the second constituent assembly met to establish a framework for drafting a post-Mubarak constitution.[203][204]

29 June: Mohamed Morsi took a symbolic oath of office in Tahrir Square, affirming that the people are the source of power.[205][206][207]

30 June: Morsi was sworn in as Egypt's first democratically elected president before the Supreme Constitutional Court at the podium used by US President Barack Obama to reach out to the Islamic world in 2009 in his A New Beginning speech.[208][209][210][211][212]

Under President Mohamed Morsi

[edit]November 2012 declaration

[edit]On 22 November 2012, Morsi issued a declaration immunizing his decrees from challenge and attempting to protect the work of the constituent assembly drafting the new constitution.[213] The declaration required a retrial of those acquitted of killing protesters, and extended the constituent assembly's mandate by two months. The declaration also authorised Morsi to take any measures necessary to protect the revolution. Liberal and secular groups walked out of the constituent assembly because they believed that it would impose strict Islamism, while the Muslim Brotherhood supported Morsi.[214][215]

Morsi's declaration was criticised by Constitution Party leader Mohamed ElBaradei (who said that he had "usurped all state powers and appointed himself Egypt's new pharaoh"),[216] and led to violent protests throughout the country.[217] Protesters again erected tents in Tahrir Square, demanding a reversal of the declaration and the dissolving of the constituent assembly. A "huge protest" was planned for Tuesday, 27 November,[218] with clashes reported between protesters and police.[219] The declaration was also condemned by Amnesty International UK.[220]

In April 2013 a youth group was created opposing Morsi and attempting to collect 22 million signatures by 30 June 2013 (the first anniversary of his presidency) on a petition demanding early presidential elections. This triggered the June 2013 protests. Although protests were scheduled for 30 June, opponents began gathering on the 28th.[221] Morsi supporters (primarily from Islamic parties) also protested that day.[222] On 30 June the group organised large protests in Tahrir Square and the presidential palace demanding early presidential elections, which later spread to other governorates.[223]

June—July 2013 protests and overthrow

[edit]On 30 June 2013, the first anniversary of Morsi's inauguration as president, millions of Egyptians protested against him, demanding he step down from office. Morsi refused to resign. A 48-hour ultimatum was issued to him, demanding that he respond to the demands of the Egyptians,[224] and on 3 July 2013, the President of Egypt was overthrown. Unlike the imposition of martial law which followed the 2011 resignation of Hosni Mubarak, on 4 July 2013, a civilian senior jurist Adly Mansour was appointed interim president and was sworn in over the new government following Morsi's removal. Mansour had the right to issue constitutional declarations and vested executive power in the Supreme Constitutional Court, giving him executive, judicial and constitutional power.[225] Morsi refused to accept his removal from office, and many supporters vowed to reinstate him. They originally intended their sit-ins to celebrate Morsi's first anniversary, but they quickly became opposed to the new authorities.[226] Their sit-ins were dispersed on 14 August by security forces, leading to at least 904 civilian deaths and 8 police officers killed.[227][228]

On 18 January 2014, the interim government institutionalised a new constitution following a referendum in which 98.2% of voters were supportive. Participation was low with only 38.6% of registered voters participating[229] although this was higher than the 33% who voted in a referendum during Morsi's tenure.[230] On 26 March 2014, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, the head of the Egyptian Armed Forces, who at this time was in control of the country, resigned from the military, announcing he would stand as a candidate in the 2014 presidential election.[231] The poll, which had a 47% turnout, and was held between 26 and 28 May 2014, resulted in a resounding victory for Sisi, who was then sworn into office as President of Egypt on 8 June 2014.[232][233]

Protests by city

[edit]Cairo

[edit]Cairo has been at the centre of the revolution; the largest protests were held in downtown Tahrir Square, considered the "protest movement's beating heart and most effective symbol".[234] During the first three days of the protests there were clashes between the central security police and demonstrators, but on 28 January the police withdrew from all of Cairo. Citizens formed neighbourhood-watch groups to maintain order, and widespread looting was reported. Traffic police were reintroduced to Cairo the morning of 31 January.[235] Media reports initially claimed that up to one million protesters[236] gathered in the square, leading to widespread coverage of the massive turnout. However, other analyses suggested that such estimates might have been overstated. A crowd-size analysis based on Tahrir Square's physical dimensions and density pointed to smaller numbers, suggesting a maximum capacity of 200,000 to 250,000 people within the square and surrounding areas.[237][238][239] During the protests, reporters Natasha Smith, Lara Logan and Mona Eltahawy were sexually assaulted while covering the events.[240][241][242][243]

Alexandria

[edit]

Alexandria, home of Khaled Saeed, experienced major protests and clashes with police. There were few confrontations between demonstrators, since there were few Mubarak supporters (except for a few police-escorted convoys). The breakdown of law and order, including the general absence of police from the streets, continued until the evening of 3 February. Alexandria's protests were notable for the joint presence of Christians and Muslims in the events following the church bombing on 1 January, which sparked protests against the Mubarak regime.

Mansoura

[edit]In the northern city of Mansoura, there were daily protests against the Mubarak regime beginning on 25 January; two days later, the city was called a "war zone".[citation needed] On 28 January, 13 were reported dead in violent clashes; on 9 February, 18 more protesters died. One protest, on 1 February, had an estimated attendance of one million. The remote city of Siwa had been relatively calm,[244] but local sheikhs reportedly in control put the community under lockdown after a nearby town was burned.[245]

Suez

[edit]Suez also saw violent protests. Eyewitness reports suggested that the death toll was high, although confirmation was difficult due to a ban on media coverage in the area.[246] Some online activists called Suez Egypt's Sidi Bouzid (the Tunisian city where protests began).[247] On 3 February, 4,000 protesters took to the streets to demand Mubarak's resignation.[248] A labour strike took place on 8 February,[249] and large protests were held on 11 February.[250] The MENA news agency reported the death of two protestors and one police officers on 26 January.[251]

Other cities

[edit]There were protests in Luxor.[252] On 11 February police opened fire on protesters in Dairut, tens of thousands of protesters took to the streets of Shebin el-Kom, thousands protested in El-Arish on the Sinai Peninsula,[250] large protests took place in the southern cities of Sohag and Minya and nearly 100,000 people protested in and around local-government headquarters in Ismaïlia.[250] Over 100,000 protesters gathered on 27 January in front of the city council in Zagazig.[253] Bedouins in the Sinai Peninsula fought security forces for several weeks.[254] As a result of the decreased military border presence, Bedouin groups protected the borders and pledged their support of the revolution.[255] However, despite mounting tension among tourists no protests or civil unrest occurred in Sharm-El-Sheikh.[256]

Deaths

[edit]

Before the protests six cases of self-immolation were reported, including a man arrested while trying to set himself afire in downtown Cairo.[257] The cases were inspired by (and began one month after) the acts of self-immolation in Tunisia which triggered the Tunisian revolution. The self-immolators included Abdou Abdel-Moneim Jaafar,[258] Mohammed Farouk Hassan,[259] Mohammed Ashour Sorour[260] and Ahmed Hashim al-Sayyed, who later died from his injuries.[261]

As of 30 January, Al Jazeera reported as many as 150 deaths in the protests.[262]

By 29 January, 2,000 people were confirmed injured.[263] That day, an employee of the Azerbaijani embassy in Cairo was killed on their way home from work;[264] the following day, Azerbaijan sent a plane to evacuate citizens[265] and opened a criminal investigation into the killing.[266]

Funerals for those killed during the "Friday of Anger" were held on 30 January. Hundreds of mourners gathered, calling for Mubarak's removal.[267] By 1 February the protests left at least 125 people dead,[268] although Human Rights Watch said that UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay claimed that as many as 300 might have died in the unrest. The unconfirmed tally included 80 Human-Rights-Watch-verified deaths at two Cairo hospitals, 36 in Alexandria and 13 in Suez;[269][270][271] over 3,000 people were reported injured.[269][271]

An Egyptian governmental fact-finding commission about the revolution announced on 19 April that at least 846 Egyptians died in the nearly three-week-long uprising.[272][273][274] One prominent Egyptian who was killed was Emad Effat, a senior cleric at the Dar al-Ifta al-Misriyyah school of Al-Azhar University. He died 16 December 2011, after he was shot in front of the cabinet building.[275] At Effat's funeral the following day, hundreds of mourners chanted "Down with military rule".[275][276]

International reaction

[edit]International response to the protests was initially mixed,[277] although most governments called for peaceful action on both sides and a move towards reform. Most Western nations expressed concern about the situation, and many governments issued travel advisories and attempted to evacuate their citizens from Egypt.[278]

The European Union Foreign Affairs Chief said, "I also reiterate my call upon the Egyptian authorities to urgently establish a constructive and peaceful way to respond to the legitimate aspirations of Egyptian citizens for democratic and socioeconomic reforms."[279] The United States, the United Kingdom, France and Germany issued similar statements calling for reform and an end to violence against peaceful protesters. Many states in the region expressed concern and supported Mubarak; Saudi Arabia issued a statement "strongly condemn[ing]" the protests,[280] while Tunisia and Iran supported them. Israel was cautious, with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu asking his government ministers to maintain silence and urging Israel's allies to curb their criticism of President Mubarak;[281][282] however, an Arab-Israeli parliamentarian supported the protests. Solidarity demonstrations for the protesters were held worldwide.

Non-governmental organizations expressed concern about the protests and the heavy-handed state response, with Amnesty International describing attempts to discourage the protests as "unacceptable".[283] Many countries (including the US, Israel, the UK and Japan) issued travel warnings or began evacuating their citizens, and multinational corporations began evacuating expatriate employees.[284] Many university students were also evacuated.

Post-ouster

[edit]Many nations, leaders and organizations hailed the end of the Mubarak regime, and celebrations were held in Tunisia and Lebanon. World leaders, including German Chancellor Angela Merkel and UK Prime Minister David Cameron, joined in praising the revolution.[285] US President Barack Obama praised the achievement of the Egyptian people and encouraged other activists, saying "Let's look at Egypt's example".[286] Amid growing concern for the country, Cameron was the first world leader to visit Egypt, ten days after Mubarak's resignation. A news blackout was lifted as the prime minister landed in Cairo for a brief five-hour stopover, hastily added to the beginning of a planned tour of the Middle East.[287] On 15 March, United States Secretary of State Hillary Clinton visited Egypt; she was the highest-ranking US official to visit the country since the handover of power from Mubarak to the military. Clinton urged military leaders to begin the process of a democratic transition, offering support to protesters and reaffirming ties between the two nations.[288]

Results

[edit]On 29 January Mubarak indicated that he would change the government because, despite the crossing of a "point of no return", national stability and law and order must prevail. He asked the government, formed only months ago, to step down and promised that a new government would be formed.[289] Mubarak appointed Omar Suleiman, head of Egyptian Intelligence, vice president and Ahmed Shafik prime minister.[290] On 1 February, he said he would stay in office until the next election in September, and then leave. Mubarak promised political reform, but made no offer to resign.

The Muslim Brotherhood joined the revolution on 30 January, calling on the military to intervene and all opposition groups to unite against Mubarak. It joined other opposition groups in electing Mohamed el Baradei to lead an interim government.[291]

Many of the Al-Azhar imams joined protesters throughout the country on 30 January.[292] Christian leaders asked their congregations not to participate in the demonstrations, although a number of young Christian activists joined protests led by New Wafd Party member Raymond Lakah.[293]

On 31 January, Mubarak swore in his new cabinet in the hope that the unrest would fade. Protesters in Tahrir Square continued demanding his ouster, since a vice-president and prime minister were already appointed.[294] He told the new government to preserve subsidies, control inflation and provide more jobs.[295]

On 1 February Mubarak said that although his candidacy had been announced by high-ranking members of his National Democratic Party,[296] he never intended to run for reelection in September.[297] He asked parliament for reforms:

According to my constitutional powers, I call on parliament in both its houses to discuss amending article 76 and 77 of the constitution concerning the conditions on running for presidency of the republic and it sets specific a period for the presidential term. In order for the current parliament in both houses to be able to discuss these constitutional amendments and the legislative amendments linked to it for laws that complement the constitution and to ensure the participation of all the political forces in these discussions, I demand parliament to adhere to the word of the judiciary and its verdicts concerning the latest cases which have been legally challenged.

— Hosni Mubarak, 1 February 2011[298]

Opposition groups, including the Muslim Brotherhood (MB), repeated their demand that Mubarak resign; after the protests turned violent, the MB said that it was time for military intervention.[299] Mohamed ElBaradei, who said he was ready to lead a transitional government,[300] was a consensus candidate from a unified opposition, which included the 6 April Youth Movement, the We Are All Khaled Said Movement, the National Association for Change, the 25 January Movement, Kefaya and the Muslim Brotherhood.[301] ElBaradei formed a "steering committee".[302] On 5 February, talks began between the government and opposition groups for a transitional period before elections.

The government cracked down on the media, halting internet access[303] (a primary means of opposition communication) with the help of London-based Vodafone.[304][305][306] Journalists were harassed by supporters of the regime, eliciting condemnation from the Committee to Protect Journalists, European countries and the United States. Narus, a subsidiary of Boeing, sold the Mubarak government surveillance equipment to help identify dissidents.[307]

Reforms

[edit]The revolution's primary demands, chanted at every protest, were bread (also jobs and other material needs), freedom, social justice and human dignity.[308] The fulfillment of these demands has been uneven and debatable. Demands stemming from the main four include the following:

| Demand | Status | Date |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Resignation of President Mubarak | Met | 11 February 2011 |

| 2. New minimum and maximum wages | Partially met | The basic minimum wage rose from E£246 to E£870 on 22 March 2015[310] |

| 3. Canceling emergency law | Met[311] | 31 May 2012 |

| 4. Dismantling the State Security Investigations Service | Claimed met;[312] reneged in 2013[313] | 31 May 2012 |

| 5. Announcement by vice-president Omar Suleiman that he would not run for president | Claimed met;[314] reneged in April 2012 | 3 February 2011 |

| 6. Dissolution of parliament | Met | 13 February 2011 |

| 7. Release of those imprisoned since 25 January | Ongoing; More have been arrested and faced military trials under the SCAF | |

| 8. Ending the curfew | Met[315] | 15 June 2011 |

| 9. Removing the SSI-controlled university police | Claimed met | 3 March 2011 |

| 10. Investigation of officials responsible for violence against protesters | Ongoing | |

| 11. Firing Minister of Information Anas el-Fiqqi and halting media propaganda | Claimed met; minister fired, however ministry still exists and propaganda ongoing[316] | |

| 12. Reimbursing shop owners for losses during the curfew | Announced; not met | 7 February 2011 |

| 13. Announcing demands on government television and radio | Claimed met | 11–18 February 2011 |

| 14. Dissolution of the NDP | Met | 16 April 2011 |

| 15. Arrest, interrogation and trial of Hosni Mubarak and his sons, Gamal and Alaa | Met[317] | 24 May 2011 |

| 16. Transfer of power from SCAF to civilian council | Met[318] | 30 June 2012 |

On 17 February, an Egyptian prosecutor ordered the detention of three former ministers (interior minister Habib el-Adli, tourism minister Zuhair Garana and housing minister Ahmed el-Maghrabi) and steel magnate Ahmed Ezz pending trial for wasting public funds. The public prosecutor froze the bank accounts of Adli and his family following accusations that over E£4 million ($680,000) were transferred to his personal account by a businessman. The foreign minister was requested to contact European countries to freeze the other defendants' accounts.[319]

That day, the United States announced that it would give Egypt $150 million in aid to help it transition towards democracy. US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said that William J. Burns (undersecretary of state for political affairs) and David Lipton (a senior White House adviser on international economics) would travel to Egypt the following week.[319]

On 19 February a moderate Islamic party which had been banned for 15 years, Al-Wasat Al-Jadid (Arabic: حزب الوسط الجديد, New Center Party), was finally recognised by an Egyptian court. The party was founded in 1996 by activists who split from the Muslim Brotherhood and sought to create a tolerant, liberal Islamic movement, but its four attempts to register as an official party were rejected. That day, Prime Minister Ahmed Shafiq also said that 222 political prisoners would be released. Shafiq said that only a few were detained during the uprising; he put the number of remaining political prisoners at 487, but did not say when they would be released.[320] On 20 February Yehia El Gamal [ar], an activist and law professor, accepted on television the position of deputy prime minister. The next day, the Muslim Brotherhood announced that it would form a political party, the Freedom and Justice Party led by Saad Ketatni, for the upcoming parliamentary election.[321][322][323] A spokesperson said, "When we talk about the slogans of the revolution – freedom, social justice, equality – all of these are in the Sharia (Islamic law)."[324]

On 3 March, Prime Minister Shafiq submitted his resignation to the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces. The SCAF appointed Essam Sharaf, a former transportation minister and a vocal critic of the regime following his resignation after the 2006 Qalyoub rail accident, to replace Shafik and form a new government. Sharaf's appointment was seen as a concession to protesters, since he was actively involved in the events in Tahrir Square.[325][326][327] Sharaf appointed former International Court of Justice judge Nabil Elaraby foreign minister and Mansour El Essawi as interior minister.[328][329]

On 16 April the Higher Administrative Court dissolved the former ruling National Democratic Party (NDP), ordering its funds and property to be transferred to the government.[330] On 24 May it was announced that Hosni Mubarak and his sons, Gamal and Alaa, would be tried for the deaths of anti-government protesters during the revolution.[331]

Trials

[edit]Mubarak's resignation was followed by a series of arrests of, and travel bans on, high-profile figures on charges of causing the deaths of 300–500 demonstrators, injuring 5,000 more, embezzlement, profiteering, money laundering and human rights abuses. Among those charged were Mubarak, his wife Suzanne, his sons Gamal and Alaa, former interior minister Habib el-Adly, former housing minister Ahmed El-Maghrabi, former tourism minister Zoheir Garana and former secretary for organizational affairs of the National Democratic Party Ahmed Ezz.[332] Mubarak's ouster was followed by allegations of corruption against other government officials and senior politicians.[333][334] On 28 February 2011, Egypt's top prosecutor ordered an assets freeze on Mubarak and his family.[335] This was followed by arrest warrants, travel bans and asset freezes for other public figures, including former parliament speaker Fathi Sorour and former Shura Council speaker Safwat El Sherif.[336][337] Arrest warrants were issued for financial misappropriations by public figures who left the country at the outbreak of the revolution, including former trade and industry minister Rachid Mohamed Rachid and businessman Hussein Salem; Salem was believed to have fled to Dubai.[338] Trials of the accused officials began on 5 March 2011, when former interior minister Habib el-Adli appeared at the Giza Criminal Court in Cairo.[339]

In March 2011 Abbud al-Zumar, one of Egypt's best-known political prisoners, was freed after 30 years. Founder and first emir of the Egyptian Islamic Jihad, he was implicated on 6 October 1981 assassination of Anwar Sadat.[340]

On 24 May, Mubarak was ordered to stand trial on charges of premeditated murder of peaceful protestors during the revolution; if convicted, he could face the death penalty. The list of charges, released by the public prosecutor, was "intentional murder, attempted killing of some demonstrators ... misuse of influence and deliberately wasting public funds and unlawfully making private financial gains and profits".[12]

Analysis

[edit]Regional instability

[edit]The Egyptian and Tunisian revolutions sparked a wave of uprisings, with demonstrations spreading across the Middle East and North Africa. Algeria, Bahrain, Iran, Jordan, Libya, Morocco, Yemen and Syria witnessed major protests, and minor demonstrations occurred in Iraq, Kuwait, Mauritania, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Somalia[citation needed] and Sudan.

The Egyptian protests in Egypt were not centred around religion-based politics, but nationalism and social consciousness.[341] Before the uprising, the best-organised and most-prominent opposition movements in the Arab world usually came from Islamist organisations with members who were motivated and ready to sacrifice. However, secular forces emerged from the revolution espousing principles shared with religious groups: freedom, social justice and dignity. Islamist organisations emerged with a greater freedom to operate. Although the cooperative, inter-faith revolution was no guarantee that partisan politics would not re-emerge in its wake, its success represented a change from the intellectual stagnation (created by decades of repression) which pitted modernity and Islamism against one another. Islamists and secularists are faced with new opportunities for dialogue on subjects such as the role of Islam and Sharia in society, freedom of speech and the impact of secularism on a predominantly Muslim population.[342]

Despite the optimism surrounding the revolution, commentators expressed concern about the risk of increased power and influence for Islamist forces in the country and region and the difficulty of integrating different groups, ideologies and visions for the country. Journalist Caroline Glick wrote that the Egyptian revolution foreshadowed a rise in religious radicalism and support for terrorism, citing a 2010 Pew Opinion poll which found that Egyptians supported Islamists over modernizers by an over two-to-one margin.[343] Another journalist, Shlomo Ben-Ami, said that Egypt's most formidable task was to refute the old paradigm of the Arab world which sees the only choices for regimes repressive, secular dictatorships or repressive theocracies. Ben-Ami noted that with Islam a central part of the society, any emergent regime was bound to be attuned to religion. In his view, a democracy which excluded all religion from public life (as in France) could succeed in Egypt but no genuine Arab democracy could disallow the participation of political Islam.[344]

Since the revolution Islamist parties (such as the Muslim Brotherhood) have strengthened in the democratic landscape, leading constitutional change, voter mobilization and protests.[345][346] This was a concern of the secular and youth movements, who wanted elections to be held later so they could catch up to the already-well-organised groups. Elections were held in September 2011, with Liberty and Justice (the Muslim Brotherhood party) winning 48.5 per cent of the vote. In 2014 in Upper Egypt, several newspapers reported that Upper Egypt wanted to secede from the rest of the country to improve its standard of living.[347]

Alexandria church bombing

[edit]Early on New Year's Day 2011 a bomb exploded in front of an Alexandria church, killing 23 Coptic Christians. Egyptian officials said that "foreign elements" were behind the attack.[348] Other sources claim that the bomb killed 21 people only and injured more than 70.[349][350] Some Copts accused the Egyptian government of negligence;[351] after the attack, many Christians protested in the streets (with Muslims joining later). After clashing with police, protesters in Alexandria and Cairo shouted slogans denouncing Mubarak's rule[352][353][354] in support of unity between Christians and Muslims. Their sense of being let down by national security forces was cited as one of the first grievances sparking 25 January uprising.[355] On 7 February a complaint was filed against Habib al-Adly (interior minister until Mubarak dissolved the government during the protests' early days), accusing him of directing the attack.[356]

Role of women

[edit]

Egyptian women have been participating actively in the revolution, in the same way that they played an active role in the strike movement in the few last years, in several cases pressurizing the men to join the strikes.[358] In earlier protests in Egypt, women only accounted for about 10 per cent of the protesters, but on Tahrir Square they accounted for about 40 to 50 per cent in the days leading up to the fall of Mubarak. Women, with and without veils, participated in the defence of the square, set up barricades, led debates, shouted slogans and, together with the men, risked their lives.[358] Some participated in the protests, were present in news clips and on Facebook forums and were part of the revolution's leadership during the Egyptian revolution. In Tahrir Square, female protesters (some with children) supported the protests. The diversity of the protesters in Tahrir Square was visible in the women who participated; many wore head scarves and other signs of religious conservatism, while others felt free to kiss a friend or smoke a cigarette in public. Women organised protests and reported events; female bloggers, such as Leil Zahra Mortada, risked abuse or imprisonment by keeping the world informed of events in Tahrir Square and elsewhere.[359] Among those who died was Sally Zahran, who was beaten to death during one of the demonstrations. NASA reportedly planned to name one of its Mars exploration spacecraft in Zahran's honour.[360]

The participation and contributions by Egyptian women to the protests were attributed to the fact that many (especially younger women) were better educated than previous generations and represent more than half of Egyptian university students. This is an empowering factor for women, who have become more present and active publicly. The advent of social media also provided a tool for women to become protest leaders.[359]

Role of the military

[edit]

The Egyptian Armed Forces initially enjoyed a better public reputation than the police did; the former was seen as a professional body protecting the country, and the latter was accused of systemic corruption and lawless violence. However, when the SCAF cracked down on protesters after becoming the de facto ruler of Egypt the military's popularity decreased.[361][362] All four Egyptian presidents since the 1950s have a military background. Key Egyptian military personnel include defence minister Tantawi and armed forces chief of staff Sami Hafez Enan.[363][364] The Egyptian military numbers about 468,500 active personnel, plus a reserve of 479,000.[365]

As head of Egypt's armed forces, Tantawi has been described as "aged and change-resistant" and is attached to the old regime. He has used his position as defence minister to oppose economic and political reform he saw as weakening central authority. Other key figures (Sami Hafez Anan chief among them) are younger, with closer connections to the US and the Muslim Brotherhood. An important aspect of the relationship between the Egyptian and American military establishments is the $1.3 billion in annual military aid provided to Egypt, which pays for American-made military equipment and allows Egyptian officers to train in the US. Guaranteed this aid package, the ruling SCAF is resistant to reform.[366][367][368] One analyst, conceding the military's conservatism, says it has no option but to facilitate democratisation. It will have to limit its political role to continue good relations with the West, and cannot restrict Islamist participation in a genuine democracy.[344]

The military has led a violent crackdown on the Egyptian revolution since the fall of Mubarak. On 9 March 2011 military police violently dispersed a sit-in in Tahrir Square, arresting and torturing protesters. Seven female protesters were forcibly subjected to virginity tests.[369] During the night of 8 April 2011 military police attacked a sit-in in Tahrir Square by protesters and sympathetic military officers, killing at least one.[370] On 9 October the Egyptian military crushed protesters under armed personnel carriers and shot live ammunition at a demonstration in front of the Maspero television building, killing at least 24.[371] On 19 November the military and police engaged in a continuous six-day battle with protestors in the streets of downtown Cairo and Alexandria, killing nearly 40 and injuring over 2,000.[372] On 16 December 2011 military forces dispersed a sit-in at the Cabinet of Ministers building, killing 17.[373] Soldiers fired live ammunition and attacked from the rooftop with Molotov cocktails, rocks and other missiles.[374]

Impact on foreign relations

[edit]Foreign governments in the West (including the US) regarded Mubarak as an important ally and supporter in the Israeli–Palestinian peace negotiations.[44] After wars with Israel in 1948, 1956, 1967 and 1973, Egypt signed a peace treaty in 1979 (provoking controversy in the Arab world). According to the 1978 Camp David Accords (which led to the peace treaty), Israel and Egypt receive billions of dollars in aid annually from the United States; Egypt received over US$1.3 billion in military aid each year, in addition to economic and development assistance.[375] According to Juan Cole many Egyptian youth felt ignored by Mubarak, feeling that he put the interests of the West ahead of theirs.[376] The cooperation of the Egyptian regime in enforcing the blockade of the Gaza Strip was deeply unpopular with the Egyptian public.[377]

Online activism and social media

[edit]

The 6 April Youth Movement (Arabic: حركة شباب 6 أبريل) is an Egyptian Facebook group begun in spring 2008 to support workers in El-Mahalla El-Kubra, an industrial town, who were planning to strike on 6 April. Activists called on participants to wear black and stay home the day of the strike. Bloggers and citizen journalists used Facebook, Twitter, Flickr, blogs and other media tools to report on the strike, alert their networks about police activity, organize legal protection and draw attention to their efforts. The New York Times has called it the political Facebook group in Egypt with the most dynamic debates.[378] In March 2012 it had 325,000[379] predominantly young and members, most previously inactive politically, whose concerns included free speech, nepotism in government and the country's stagnant economy. Their Facebook forum features intense and heated discussions, and is frequently updated.

We are all Khaled Said is a Facebook group which formed in the aftermath of Said's beating and death. The group attracted hundreds of thousands of members worldwide, playing a prominent role in spreading (and drawing attention to) the growing discontent. As the protests began, Google executive Wael Ghonim revealed that he was behind the account. He was later detained for a few days until the government was able to get a hold of certain information that they needed. Many questions were left around that subject, no one really understood what had actually happened or what has had been said.[380] In a TV interview with SCAF members after the revolution, Abdul Rahman Mansour (an underground activist and media expert) was disclosed as sharing the account with Ghonim.[381] Another online contribution was made by Asmaa Mahfouz, an activist who posted a video challenging people to publicly protest.[382] Facebook had previously suspended the group because some administrators were using pseudonyms, a violation of the company's terms of service.[383]

Social media has been used extensively.[384][385][386][387] As one Egyptian activist tweeted during the protests, "We use Facebook to schedule the protests, Twitter to coordinate, and YouTube to tell the world."[388] Internet censorship has also been extensive, in some cases to the extent of taking entire nations virtually offline.[389]

Facebook, Twitter and blogging helped spread the uprising. Egyptian businessman Khaled Said was beaten to death by police in June 2010, reportedly in retaliation for a video he posted showing Egyptian police sharing the spoils of a drug bust. Wael Ghonim's memorial Facebook page to Said grew to over 400,000 followers, creating an online arena where protestors and those discontented with the government could gather and organise. The page called for protests on 25 January, later known as the "Day of Wrath". Hundreds of thousands of protestors flooded the streets to show their discontent with murder and corruption in their country. Ghonim was jailed on 28 January, and released 12 days later.

Egyptian activist and 6 April Youth Movement member Asmaa Mahfouz posted a video urging the Egyptian people to meet her at Tahrir Square, rise up against the government and demand democracy. In the video, she spoke about four protesters who had immolated themselves in protest of 30 years of poverty and degradation. On 24 January Mahfouz posted another video relating efforts made in support of the protest, from printing posters to creating flyers. The videos were posted on Facebook and then YouTube. The day after her last video post, hundreds of thousands of Egyptians poured into the streets in protest.

Since 25 January 2011, videos (including those of a badly beaten Khaled Said, disproving police claims that he had choked to death), tweets and Facebook comments have kept the world abreast of the situation in Egypt. Amir Ali documents the ways in which social media was used by Egyptian activists, Egyptian celebrities and political figures abroad to fan the protests.[390]

Democracy Now! journalist Sharif Abdel Kouddous provided live coverage and tweets from Tahrir Square during the protests, and was credited with using social media to increase awareness of the protests.[391][392] The role of social media in the Egyptian uprising was debated in the first edition of the Dubai Debates: "Mark Zuckerberg – the new hero of the Arab people?"[393] Amir Ali has argued that, based in part on the Egyptian revolution, social media may be an effective tool in developing nations.[394]

Critics who downplay the influence of social networking on the Arab Spring cite several points:

- Fewer than 20 per cent of Egyptians had internet access, and the internet reached less than 40 per cent of the country[395]

- Social-networking sites were generally unpopular in the Middle East,[396][397]

- Such sites were not sufficiently private to evade authorities[398]

- Many people did not trust social networking as a news source[399]

- Social-networking sites were promoted by the media[400]

- Social-networking sites did not involve non-activists in the revolution[401]

Some protesters discouraged the use of social media. A widely circulated pamphlet by an anonymous activist group titled "How to Protest Intelligently" (Arabic: كيف للاحتجاج بذكاء؟), asked readers "not to use Twitter or Facebook or other websites because they are all being monitored by the Ministry of the Interior".[402]

Television, particularly live coverage by Al Jazeera English and BBC News, was important to the revolution; the cameras provided exposure, preventing mass violence by the government in Tahrir Square (in contrast to the lack of live coverage and more-widespread violence in Libya).[403] Its use was important in order to portray the violence of the Egyptian government, as well as, building support for the revolution through several different mediums. On one front was social media giving minute by minute updates via YouTube, Facebook and Twitter, and in the other hand was the use of the mainstream media to report to a wider audience about the overall developments occurring in Egypt.[404] The ability of protesters to focus their demonstrations on a single area (with live coverage) was fundamental in Egypt but impossible in Libya, Bahrain and Syria, irrespective of social-media use. A social-media expert launched a network of messages with the hashtag #jan25 on 11 February 2011, when Mubarak's resignation was announced.[405]

Social media helped secure solidarity for the revolutionaries from people outside of Egypt. This is evident through movements like the "March of Millions", "Voice of Egypt Abroad", "Egyptians Abroad in Support of Egypt" and "New United Arab States", who had their inception during the revolution inside the realms of Twitter and Facebook.[404]

Journalism scholar Heather Ford studied the use of infoboxes and cleanup templates in the Wikipedia article regarding the revolution. Ford claims that infoboxes and cleanup tags were used as objects of "bespoken-code" by Wikipedia editors. By using these elements, editors shaped the news narrative in the first 18 days of the revolution. Ford used the discussion page and the history of edits to the page. She shows how political cartoons were removed, and how the number of casualties became a source of heated debate. Her research exemplifies how editors coordinated and prioritised work on the article, but also how political events are represented through collaborative journalism.[406]

Role of media disruption on 28 January 2011

[edit]During the early morning hours of 28 January the Mubarak regime shut down internet and cell phone networks in the whole country. This media shutdown was likely one of the reasons why the numbers of protestors exploded on 28 January.

While the regime disrupted the media, people needed to engage in face-to-face communication on a local level, which the regime could not monitor or control. In such a situation it is more likely that radicals will influence their neighbors, who are not able to see the public opinion displayed in social media, therefore these people are then more likely to also engage in civil unrest.[407]

This vicious circle can be explained through a threshold model of collective behaviour, which states that people are more likely to engage in risky actions if other people inside their networks (neighbours, friends, etc.) have taken action. Radicals have a small threshold and are more likely to form new networks during an information blackout, influencing the people.