Enone–alkene cycloadditions

In organic chemistry, enone–alkene cycloadditions are a version of the [2+2] cycloaddition. This reaction involves an enone and alkene as substrates. Although the concerted photochemical [2+2] cycloaddition is allowed, the reaction between enones and alkenes is stepwise and involves discrete diradical intermediates.[1]

History

[edit]This section is missing information about structure pic for "carvone camphor"; doi:10.1016/0009-2614(82)83182-5 has one. (February 2025) |

In 1908, it was reported that exposure of carvone to "Italian sunlight" for one year gives carvone-camphor.[2] Subsequent investigations demonstrated the utility of the photochemical [2+2] cycloaddition of enones to alkenes, requiring only "sunlight in California for 6.5 months".[3][4]

Mechanism

[edit]In spite of the stepwise, radical mechanism, both stereoselective intra- and intermolecular variants have emerged. Cyclic enones are employed, otherwise competitive cis-trans isomerization ensues.

The mechanism of [2+2] photocyclization is proposed to begin with photoexcitation of the enone to a singlet excited state. The singlet state is typically very short lived, and decays by intersystem crossing to the triplet state. At this point, the enone forms an exciplex with the ground state alkene, eventually giving the triplet diradical. Spin inversion to the singlet diradical allows closure to the cyclobutane.[5] As an alternative a pericyclic reaction mechanism is proposed, in which after intersystem crossing a radical cation and a radical anion are formed, which then recombine to the cyclobutane.[6]

Scope and limitations

[edit]Enone–alkene cycloadditions can produce two isomers, depending on the orientation of substituents on the alkene and the enone carbonyl group. When the enone carbonyl and substituent of highest priority are proximal, the isomer is termed "head-to-head." When the enone carbonyl and substituent are distal, the isomer is called "head-to-tail." Selectivity for one of these isomers depends on both steric and electronic factors (see below).

The regiochemistry of the reaction is controlled primarily by two factors: steric interactions and electrostatic interactions between the excited enone and alkene. In their excited state, the polarity of enones is reversed so that the β carbon possesses a partial negative charge. In the transition state for the first bond formation, the alkene tends to align itself so that the negative end of its dipole points away from the β carbon of the enone.[7]

Steric interactions encourage the placement of large substituents on opposite sides of the new cyclobutane ring.[7]

If the enone and alkene are contained in rings of five atoms or fewer, double-bond configuration is preserved. However, when larger rings are used, double bond isomerization during the reaction becomes a possibility. This energy-wasting process competes with cycloaddition[8] and is evident in reactions that yield mixtures of cis- and trans-fused products.

Diastereofacial selectivity is highly predictable in most cases. The less hindered faces of the enone and alkene react.[9]

Intramolecular enone–alkene cycloaddition may give either "bent" or "straight" products depending on the reaction regioselectivity. When the tether between the enone and alkene is two atoms long, bent products predominate due to the rapid formation of five-membered rings.[10] Longer tethers tend to give straight products.[11]

The tether can also be attached at the 2 position of the enone. When the alkene is tethered here, bulky substituents at the 4 position of the enone enforce moderate diastereoselectivity.[12]

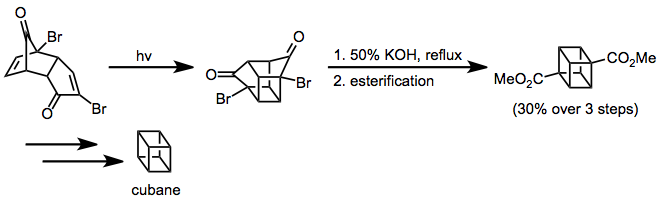

Enone–alkene cycloaddition has been applied to the synthesis of a cubane.[13] The Favorskii rearrangement established the carbon skeleton of cubane, and further synthetic manipulations provided the desired unfunctionalized target.

Methodology

[edit]Enone–alkene cycloadditions often suffer from side reactions, e.g. those associated with the diradical intermediate. These side reactions can often be minimized by a judicious choice of reaction conditions.

Dissolved oxygen is avoided since it is photoreactive.

A variety of solvents can be used. Acetone is a useful solvent, because it can serve as a triplet sensitizer. Alkane-based solvents are selected to be free of alkenes. Excitation wavelength is important. For intermolecular reactions, excess of the alkene can be employed to avoid competitive dimerization of the enone.

Glow sticks

[edit]Reverse [2+2] photocycloaddition, decomposition of 1,2-dioxetanedione, is stated as the mechanism that produces light in glow sticks.

References

[edit]- ^ Crimmins, M. T.; Reinhold, T. L. (2004). "Enone Olefin [2 + 2] Photochemical Cycloadditions". Org. React.: 297–588. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or044.02. ISBN 0471264180.

- ^ Ciamician, G.; Silber. P. (1908). "Chemische Lichtwirkungen". Ber. 41 (2): 1928. doi:10.1002/cber.19080410272.

- ^ Buchi, G. M.; Goldman, I. M. (1957). "Photochemical Reactions. VII. the Intramolecular Cyclization of Carvone to Carvonecamphor". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 79 (17): 4741. doi:10.1021/ja01574a042.

- ^ Cookson, R. C.; Crundwell, E.; Hudac, J. (1958). Chem. Ind.: 1003.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link) - ^ Loutfy, R. O.; DeMayo, P. (1972). "Primary Bond Formation in the Addition of Cyclopentenone to Chloroethylenes". Can. J. Chem. 50 (21): 3465. doi:10.1139/v72-560.

- ^ Schmeling, N.; Hunger, K.; Engler, G.; Breiten, B.; Roelling, P.; (Mixa, A.; Staudt, C.; Kleinermanns, K. (2009). "Photo-crosslinking of poly[ethene-stat-(methacrylic acid)] functionalised with maleimide side groups". Polym. Int. 58 (7): 720. doi:10.1002/pi.2583.

- ^ a b Corey, E. J.; Bass, J. D.; LeMahieu, R.; Mitra, R. B. (1964). "A Study of the Photochemical Reactions of 2-Cyclohexenones with Substituted Olefins". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 86 (24): 5570. doi:10.1021/ja01078a034.

- ^ DeMayo, P.; Nicholson, A. A.; Tchir, M. F. (1969). "Evidence for reversible intermediate formation in cyclopentenone cycloaddition". Can. J. Chem. 47 (4): 711. doi:10.1139/v69-115.

- ^ Baldwin, S. W.; Crimmins, M. T. (1982). "Total synthesis of (−)-sarracenin by photoannelation". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 104 (4): 1132. doi:10.1021/ja00368a054.

- ^ Tamura, Y.; Kita, Y.; Ishibashi, H.; Ikeda, M. (1971). "Intramolecular photocycloaddition of 3-allyloxy- and 3-allylamino-cyclohex-2-enones: formation of oxa- and aza-bicyclo[2,1,1]hexanes". J. Chem. Soc. D (19): 1167. doi:10.1039/C29710001167.

- ^ Coates, R. M.; Senter, P. D.; Baker, W. R. (1982). "Annelative ring expansion via intramolecular [2 + 2] photocycloaddition of .alpha.,.beta.-unsaturated .gamma.-lactones and reductive cleavage: synthesis of hydrocyclopentacyclooctene-5-carboxylates". J. Org. Chem. 47 (19): 3597–3607. doi:10.1021/jo00140a001.

- ^ Becker, D.; Haddad, N. (1986). "About the stereochemistry of intramolecular [2+2] photocycloadditions". Tetrahedron Lett. 27 (52): 6393. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)87817-X.

- ^ Eaton, P. E.; Cole, T. W. Jr. (1964). "Cubane". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 86 (15): 3157–3158. doi:10.1021/ja01069a041.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch