United Nations Human Rights Council

United Nations Human Rights Council | |

|---|---|

| |

| History | |

| Founded | 15 March 2006 |

| Leadership | |

President | |

| Structure | |

| Seats | African States (13) Asia-Pacific States (13) Eastern European States (6) Latin American and Caribbean States (8) Western European and Other States (7) |

| |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| The Human Rights and Alliance of Civilizations Room is the meeting room of the United Nations Human Rights Council, in the Palace of Nations in Geneva, Switzerland | |

| Website | |

| HRC at the ohchr.org | |

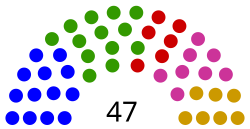

The United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC)[a] is a United Nations body whose mission is to promote and protect human rights around the world.[2] The Council has 47 members elected for staggered three-year terms on a regional group basis.[3] The headquarters of the Council are at the United Nations Office at Geneva in Switzerland.

The Council investigates allegations of breaches of human rights in United Nations member states and addresses thematic human rights issues like freedom of association and assembly,[4] freedom of expression,[5] freedom of belief and religion,[6] women's rights,[7] LGBT rights,[8] and the rights of racial and ethnic minorities.[b]

The Council was established by the United Nations General Assembly on 15 March 2006[c] to replace the United Nations Commission on Human Rights (UNCHR, herein CHR).[9] The Council works closely with the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and engages the United Nations special procedures. The Council has been strongly criticized for including member countries that engage in human rights abuses.[10][11]

Structure

[edit]The members of the General Assembly elect the members who occupy 47 seats of the Human Rights Council.[12] The term of each seat is three years, and no member may occupy a seat for more than two consecutive terms.[12] The previous CHR had a membership of 53 countries elected by the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) through a majority of those present and voting.[13]

Sessions

[edit]The UNHRC holds regular sessions three times a year, in March, June, and September.[14] The UNHRC can decide at any time to hold a special session to address human rights violations and emergencies, at the request of one-third of the member states.[15] As of November 2023[update], there had been 36 special sessions.[15]

Members

[edit]The Council consists of 47 members, elected yearly by the General Assembly for staggered three-year terms. Members are selected via the basis of equitable geographic rotation using the United Nations regional grouping system. Members are eligible for re-election for one additional term, after which they must relinquish their seat.[16] United Nations member states outside the Council serve as observer states.[17]

The seats are distributed along the following lines:[12]

- 13 for the African Group

- 13 for the Asia-Pacific Group

- 6 for the Eastern European Group

- 8 for the Latin American and Caribbean Group

- 7 for the Western European and Others Group

Current

[edit]Previous

[edit]Presidents

[edit]| No. | Name | Country | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | Jürg Lauber | 1 January 2025 – Incumbent[37] | |

| 18 | Omar Zniber | 10 January 2024 – 31 December 2024 | |

| 17 | Václav Bálek [d] | 1 January 2023 – 31 December 2023[38] | |

| 16 | Federico Villegas | 1 January 2022 – 31 December 2022[39] | |

| 15 | Nazahat Shameen Khan | 1 January 2021 – 31 December 2021[40] | |

| 14 | Elisabeth Tichy-Fisslberger | 1 January 2020 – 31 December 2020[41] | |

| 13 | Coly Seck | 1 January 2019 – 31 December 2019 | |

| 12 | Vojislav Šuc | 1 January 2018 – 31 December 2018 | |

| 11 | Joaquín Alexander Maza Martelli | 1 January 2017 – 31 December 2017 | |

| 10 | Choi Kyong-lim | 1 January 2016 – 31 December 2016[42] | |

| 9 | Joachim Rücker | 1 January 2015 – 31 December 2015 | |

| 8 | Baudelaire Ndong Ella | 1 January 2014 – 31 December 2014 | |

| 7 | Remigiusz Henczel | 1 January 2013 – 31 December 2013[43] | |

| 6 | Laura Dupuy Lasserre | 19 June 2011 – 31 December 2012 | |

| 5 | Sihasak Phuangketkeow | 19 June 2010 – 18 June 2011[44] | |

| 4 | Alex Van Meeuwen | 19 June 2009 – 18 June 2010[44] | |

| 3 | Martin Ihoeghian Uhomoibhi | 19 June 2008 – 18 June 2009 | |

| 2 | Doru Romulus Costea | 19 June 2007 – 18 June 2008 | |

| 1 | Luis Alfonso de Alba | 19 June 2006 – 18 June 2007 |

Suspensions

[edit]The General Assembly can suspend the rights and privileges of any Council member that it decides has persistently committed gross and systematic violations of human rights during its term of membership.[45] The suspension process requires a two-thirds majority vote by the General Assembly.[46] The resolution establishing the UNHRC states that "when electing members of the Council, Member States shall take into account the contribution of candidates to the promotion and protection of human rights and their voluntary pledges and commitments made thereto",[47] and that "members elected to the Council shall uphold the highest standards in the promotion and protection of human rights".[47]

Under those provisions, and in response to a recommendation made by the Council's members, on 1 March 2011 the General Assembly voted to suspend Libya's membership in the light of the situation in the country in the wake of Muammar Gaddafi's "violent crackdown on anti-government protestors";[48] Libya was reinstated as a Council member on 18 November 2011.[49]

On 7 April 2022, just days after photographic and video material of the Bucha massacre emerged, the eleventh emergency special session of the General Assembly suspended Russia from the council due to the gross and systematic violations of human rights committed during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[50] Deputy Permanent Representative Gennady Kuzmin said that Russia had withdrawn from the council earlier in the day in expectation of the vote.[51] Russia was only the second Human Rights Council member to be suspended from the UN body, after Libya in 2011, and it was the first permanent member of the UN Security Council to be suspended from any United Nations body.[52]

Directly responsible subsidiary bodies

[edit]Universal Periodic Review Working Group

[edit]An important component of the Council consists of a periodic review of all 193 UN member states, called the Universal Periodic Review (UPR).[53] The mechanism is based on reports coming from different sources, one of them being contributions from non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Each country's situation will be examined during a three-and-a-half-hour debate.[54][55]

The first cycle of the UPR took place between 2008 and 2011,[56] the second cycle between 2012 and 2016,[57] and the third cycle began in 2017 and is expected to be completed in 2021.[58]

The General Assembly resolution establishing the Council provided that "the Council shall review its work and functioning five years after its establishment".[59] The main work of the review was undertaken in an Intergovernmental Working Group established by the Council in its Resolution 12/1 of 1 October 2009.[60] The review was finalized in March 2011, by the adoption of an "Outcome" at the Council's 16th session, annexed to Resolution 16/21.[61]

First cycle: The following terms and procedures were set out in General Assembly Resolution 60/251:

- Reviews are to occur over a four-year period (48 countries per year). Accordingly, the 193[62] countries that are members of the United Nations shall normally all have such a Review between 2008 and 2011;

- The order of review should follow the principles of universality and equal treatment;

- All Member States of the Council will be reviewed while they sit at the Council and the initial members of the Council will be first;

- The selection of the countries to be reviewed must respect the principle of equitable geographical allocation;

- The first Member States and the first observatory States to be examined will be selected randomly in each regional group to guarantee full compliance with the equitable geographical allocation. Reviews shall then be conducted alphabetically.

Second cycle: HRC Resolution 16/21 brought the following changes:

- Reviews are to occur over a four-and-a-half-year period (42 countries per year). Accordingly, the 193 countries that are members of the United Nations shall normally all have such a Review between 2012 and 2016;

- The order of review will be similar to the 1st cycle;

- The length of each Review will be extended from three to three-and-a-half hours;

- The second and subsequent cycles of the review should focus on, inter alia, the implementation of the recommendations.

Similar mechanisms exist in other organizations: International Atomic Energy Agency, Council of Europe, International Monetary Fund, Organization of American States, and the World Trade Organization.[63]

Advisory Committee

[edit]The Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights was the main subsidiary body of the CHR. The Sub-Commission was composed of 26 elected human rights experts whose mandate was to conduct studies on discriminatory practices and to make recommendations to ensure that racial, national, religious, and linguistic minorities are protected by law.[64]

In 2006, the newly created UNHRC assumed responsibility for the Sub-Commission. The Sub-Commission's mandate was extended for one year (to June 2007), but it met for the final time in August 2006.[64] At its final meeting, the Sub-Commission recommended the creation of a Human Rights Consultative Committee to provide advice to the UNHRC.[65]

In September 2007, the UNHRC decided to create an Advisory Committee to provide expert advice[66] with 18 members, distributed as follows: five from African states; five from Asian states; three from Latin American and Caribbean states; three from Western European and other states; and two members from Eastern European states.[67]

Complaint procedure

[edit]The UNHRC complaint procedure was established on 18 June 2007 (by UNHRC Resolution 5/1)[68] for reporting of consistent patterns of gross and reliably attested violations of human rights and fundamental freedoms in any part of the world and under any circumstances.

The UNHRC set up two working groups for its Complaint Procedure:

- the Working Group on Communications (WGC) – consists of five experts designated by the Advisory Committee from among its members, one from each regional group. The experts serve for three years with the possibility of one renewal. The experts determine whether a complaint deserves investigation, in which case it is passed to the WGS.

- the Working Group on Situations (WGS) – has five members, appointed by the regional groups from among its members on the Council for one year, which is renewable once. The WGS meets twice a year for five working days to examine the communications transferred to it by the WGC, including the replies of states thereon, as well as the situations which are already before the UNHRC under the complaint procedure. The WGS, on the basis of the information and recommendations provided by the WGC, presents the UNHRC with a report on consistent patterns of gross and reliably attested violations of human rights and fundamental freedoms and makes recommendations to the UNHRC on the course of actions to take.[68]

- Filing a complaint

The Chairman of the WGC screens complaints for admissibility. A complaint must be in writing, and cannot be anonymous. Examples provided by the UNHRC of cases that would be considered consistent patterns of gross human rights violations include alleged deterioration of human rights of people belonging to a minority, including forced evictions, racial segregation and substandard living conditions, and alleged degrading situation of prison conditions for both detainees and prison workers, resulting in violence and death of inmates.[69] Individuals, groups, or NGOs can claim to be victims of human rights violations or that have direct, reliable knowledge of such violations.[70]

Complaints can be regarding any state, regardless of whether it has ratified a particular treaty. Complaints are confidential and the UNHRC will only communicate with the complainant, unless it decides that the complaint will be addressed publicly.[71]

The interaction with the complainant and the UNHRC during the complaints procedure will be on an as-needed basis. UNHRC Resolution 5/1, paragraph 86, emphasizes that the procedure is victims-oriented. Paragraph 106 provides that the complaint procedure shall ensure that complainants are informed of the proceedings at the key stages. The WGC may request further information from complainants or a third party.[68]

Following the initial screening a request for information will be sent to the state concerned, which shall reply within three months of the request being made. WGS will then report to the UNHRC, which will usually be in the form of a draft resolution or decision on the situation referred to in the complaint.[72]

The UNHRC will decide on the measures to take in a confidential manner as needed, but this will occur at least once a year. As a general rule, the period of time between the transmission of the complaint to the state concerned and consideration by the UNHRC shall not exceed 24 months. Those individuals or groups who make a complaint should not publicly state the fact that they have submitted a complaint.[73]

To be accepted complaints must:

- be in writing and submitted in one of the six UN official languages (Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish);

- contain a description of the relevant facts (including names of alleged victims, dates, location, and other evidence), with as much detail as possible, and shall not exceed 15 pages;

- not be manifestly politically motivated;

- not be exclusively based on reports disseminated by mass media;

- not be already dealt with by a special procedure, a treaty body, or other United Nations or similar regional complaints procedure in the field of human rights;

- be after domestic remedies have been exhausted, unless it appears that such remedies would be ineffective or unreasonably prolonged;

- not use a language that is abusive or insulting.[74]

The complaint procedure is not designed to provide remedies in individual cases or to provide compensation to alleged victims.[68]

- Effectiveness

Due to the confidential manner of the procedure, it is almost impossible to find out what complaints have passed through the procedure and also how effective the procedure is.[75]

There is a principle of non-duplication, which means that the complaint procedure cannot take up the consideration of a case that is already being dealt with by a special procedure, a treaty body or other United Nations or similar regional complaints procedure in the field of human rights.[citation needed]

On the UNHRC website under the complaints procedure section there is a list of situations referred to the UNHRC under the complaint procedure since 2006. This was only available to the public as of 2014, however generally does not give any details regarding the situations that were under consideration other than the state that was involved.[citation needed]

In some cases the information is slightly more revealing, for example a situation that was listed was the situation of trade unions and human rights defenders in Iraq that was considered in 2012, but the UNHRC decided to discontinue that consideration.[76]

The complaints procedure has been said to be too lenient due to its confidential manner.[76] Some have often questioned the value of the procedure, but 94% of states respond to the complaints raised with them.[77]

The OHCHR receives between 11,000 and 15,000 communications per year. During 2010–11, 1,451 out of 18,000 complaints were submitted for further action by the WGC. The UNHRC considered four complaints in their 19th session in 2012. The majority of the situations that have been considered have since been discontinued.[citation needed]

History shows that the procedure works almost in a petition like way; if enough complaints are received then the UNHRC is very likely to assign a special rapporteur to the state or to the issue at hand. It has been said that an advantage of the procedure is the confidential manner, which offers the ability to engage with the state concerned through a more [diplomatic] process, which can produce better results than a more adversarial process of public accusation.[76]

The procedure is considered by some a useful tool to have at the disposal on the international community for situations where naming and shaming has proved ineffective.[76] Also another advantage is that a complaint can be made against any state, regardless of whether it has ratified a particular treaty.[citation needed]

Due to the limited information that is provided on the complaints procedure it is hard to make comments on the process itself, the resources it uses versus its effectiveness.[78]

Other subsidiary bodies

[edit]In addition to the UPR, the Complaint Procedure, and the Advisory Committee, the UNHRC's other subsidiary bodies include:

- Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which replaced the CHR's Working Group on Indigenous Populations

- Forum on Minority Issues,[79] a platform for promoting dialogue and cooperation on issues pertaining to national or ethnic, religious, and linguistic minorities

- Social Forum,[80] a space for dialogue between the representatives of Member States, civil society, including grass-roots organizations, and intergovernmental organizations on issues linked with the national and international environment needed for the promotion of the enjoyment of all human rights by all. It was established in 1997 in response to concerns regarding the impact of globalization on the realization of economic, social, and cultural rights. The appointment of Iran as Chair of the 2023 HRC Social Forum, which focused on "the contribution of science, technology, and innovation to promoting human rights, including in the context of post-pandemic recovery",[81] drew condemnation.[82]

Special procedures

[edit]"Special procedures"[83][84] is the general name given to the mechanisms established by the Human Rights Council to gather expert observations and advice on human rights issues in all parts of the world. Special procedures are categorized as either thematic mandates, which focus on major phenomena of human rights abuses worldwide, or country mandates, which report on human rights situations in specific countries or territories. Special procedures can be either individuals (called "special rapporteurs" or "independent experts"), who are intended to be independent experts in a particular area of human rights, or working groups, usually composed of five members (one from each UN region). As of August 2017 there were 44 thematic and 12 country mandates.[85]

The mandates of the special procedures are established and defined by the resolution creating them.[86] Various activities can be undertaken by mandate-holders, including responding to individual complaints, conducting studies, providing advice on technical cooperation, and engaging in promotional activities. Generally the special procedures mandate-holders report to the Council at least once a year on their findings.[87]

Special procedures mandate-holders

[edit]Mandate-holders of the special procedures serve in their personal capacity, and do not receive pay for their work. The independent status of the mandate-holders is crucial to be able to fulfill their functions in all impartiality.[88] The OHCHR provides staffing and logistical support to aid each mandate-holders in carrying out their work.[89]

Applicants for Special Procedures mandates are reviewed by a Consultative Group of five countries, one from each region. Following interviews by the Consultative Group, the Group provides a shortlist of candidates to the UNHRC President. Following consultations with the leadership of each regional grouping, the President presents a single candidate to be approved by the Member states of the UNHRC at the session following a new mandate's creation or on the expiration of the term of an existing mandate holder.[90]

Country mandates must be renewed yearly by the UNHRC; thematic mandates must be renewed every three years.[87] Mandate-holders, whether holding a thematic or country-specific mandate, are generally limited to six years of service.[91][92]

The list of thematic special procedures mandate-holders can be found here: United Nations special rapporteur

Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression

[edit]

The amendments to the duties of the Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression, passed by the Human Rights Council on 28 March 2008, gave rise to sharp criticism from western countries and human rights NGOs. The additional duty is phrased thus:

- (d) To report on instances in which the abuse of the right of freedom of expression constitutes an act of racial or religious discrimination, taking into account articles 19 (3) and 20 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and general comment No. 15 of the Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, which stipulates that the prohibition of the dissemination of all ideas based upon racial superiority or hatred is compatible with the freedom of opinion and expression

(quoted from p. 67 in the official draft record[93] of the council). The amendment was proposed by Egypt and Pakistan[94] and passed by 27 votes to 15 against, with three abstentions with the support of other members of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference, China, Russia, and Cuba.[95] As a result of the amendment over 20 of the original 53 co-sponsors of the main resolution – to renew the mandate of the Special Rapporteur – withdrew their support,[95] though the resolution was carried by 32 votes to 0, with 15 abstentions.[93] Inter alia the delegates from India and Canada protested that the Special Rapporteur now has as his/her duty to report not only infringements of the rights to freedom of expression, but in some cases also employment of the rights, which "turns the special rapporteur's mandate on its head".[94]

Outside the UN, the amendment was criticised by organizations including Reporters Without Borders, Index on Censorship, Human Rights Watch,[94] and the International Humanist and Ethical Union, all of whom share the view that the amendment threatens freedom of expression.[95]

In terms of the finally cast votes, this was far from the most controversial of the 36 resolutions adapted by the 7th session of the Council. The highest dissents concerned combating defamation of religions, with 21 votes for, 10 against, and 14 abstentions (resolution 19, pp. 91–97), and the continued severe condemnation of and appointment of a Special Rapporteur for North Korea, with votes 22–7 and 18 abstentions (resolution 15, pp. 78–80).[96] There were also varying degrees of dissent for most of the various reports criticising Israel; while on the other hand a large number of resolutions were taken unanimously without voting, including the rather severe criticism of Myanmar (resolutions 31 and 32),[97] and the somewhat less severe on Sudan (resolution 16).[96]

Israel and Palestine

[edit]The mandate of the UNHCR's Special Rapporteur on the occupied Palestinian territories is to investigate human rights violations by Israel. This is because under international humanitarian law (IHL), as applied by the UNHRC, Israel is considered the occupying power in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT), and therefore has the obligation of upholding human rights throughout the territories which the special rapporteur is tasked with investigating its adherence to. This was affirmed in an October 2023 report by the UNHCR's s Francesca Albanese.[98] A July 2024 landmark opinion by the UN's top court, the International Court of Justice, also reaffirmed this, while stating that Israel should dismantle settlements in the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem, and end its "illegal" occupation of those areas and the Gaza Strip as soon as possible.[99]

2006 creation of Agenda Item 7

[edit]The Council voted on 30 June 2006 to review the "Human rights situation in Palestine and other occupied Arab territories".[100]

Item 7. Human rights situation in Palestine and other occupied Arab territories

- Human rights violations and implications of the Israeli occupation of Palestine and other occupied Arab territories

- Right to self-determination of the Palestinian people

The council voted on 30 June 2006 to make a review of alleged human rights abuses by Israel a permanent feature of every council session. The Council's special rapporteur on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict is its only expert mandate with no year of expiry, due to the ongoing nature of the occupation. The resolution, which was sponsored by Organisation of the Islamic Conference, passed by a vote of 29 to 12 with five abstentions.

April 2009: Gaza report

[edit]On 3 April 2009, South African Judge Richard Goldstone was named as the head of the independent United Nations Fact-Finding Mission to investigate international human rights and humanitarian law violations related to the Gaza War. The Mission was established by Resolution S-9/1[101] of the United Nations Human Rights Council.[102]

On 15 September 2009, the UN Fact-Finding mission released its report which found that there was evidence "indicating serious violations of international human rights and humanitarian law were committed by Israel during the Gaza conflict, and that Israel committed actions amounting to war crimes, and possibly crimes against humanity". The mission also found that there was evidence that "Palestinian armed groups committed war crimes, as well as possibly crimes against humanity, in their repeated launching of rockets and mortars into Southern Israel".[103][104][105] The mission called for referring either side in the conflict to the UN Security Council for prosecution at the International Criminal Court if they refuse to launch fully independent investigations by December 2009.[106]

Goldstone has since partially retracted the report's conclusions that Israel committed war crimes, as new evidence has shed light upon the decision making by Israeli commanders. He said, "I regret that our fact-finding mission did not have such evidence explaining the circumstances in which we said civilians in Gaza were targeted, because it probably would have influenced our findings about intentionality and war crimes."[107]

July 2015: resolution

[edit]On 3 July 2015, UNHRC voted Resolution A/HRC/29/L.35 "ensuring accountability and justice for all violations of international law in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem".[108] It passed by 41 votes in favor including the eight sitting EU members (France, Germany, Britain, Ireland, the Netherlands, Portugal, Latvia and Estonia), one against (the United States) and five absentions (India, Kenya, Ethiopia, Paraguay and the Republic of Macedonia). India explained that its abstention was due to the reference to International Criminal Court (ICC) in the resolution whereas "India is not a signatory to the Rome Statute establishing the ICC".[109]

2018 onwards

[edit]On 9 July 2021, Michael Lynk, the Special Rapporteur for Human Rights in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, addressing a session of the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva said that Israeli settlements in the West Bank amount to a war crime, and calling on countries to inflict a cost on Israel for its illegal occupation. Israel, which does not recognize Lynk's mandate, boycotted the session.[110][111][112]

On 21 March 2022, Lynk submitted a report,[113] stating that Israel's control over the West Bank and Gaza Strip amounts to apartheid, an "institutionalised regime of systematic racial oppression and discrimination".[114] The Israeli Foreign Ministry and other Israeli and Jewish organizations labelled Lynk as hostile to Israel and the report baseless.[115]

Following the 2021 Israel–Palestine crisis,[116] the council voted on 27 May 2021 to set up a United Nations fact-finding mission to investigate possible war crimes and other abuses committed in Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories.[117] The commission will report to the Human Rights Council annually from June 2022.[118] Unlike previous fact finding missions the inquiry is open ended and will examine "all underlying root causes of recurrent tensions, instability and protraction of conflict, including systematic discrimination and repression based on national, ethnic, racial or religious identity."[117]

Accusations of bias against Israel

[edit]This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Human Rights Watch agreed that the deteriorating situation in the Occupied Palestinian Territories should be considered by the Council, and urged it to look at international human rights and humanitarian law violations committed by Palestinian armed groups as well, which the Council has done.[119] HRW also called on the Council to avoid the selectivity that discredited its predecessor and urged it to hold special sessions on other urgent situations, such as that in Darfur.[120]

In 2006, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan argued that the UNHRC should not have a "disproportionate focus on violations by Israel. Not that Israel should be given a free pass. Absolutely not. But the Council should give the same attention to grave violations committed by other states as well".[121]

On 20 June 2007, Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon issued a statement that read: "The Secretary-General is disappointed at the Council's decision to single out only one specific regional item given the range and scope of allegations of human rights violations throughout the world."[122] Ban Ki-moon also reiterated the importance of investigating and upholding international humanitarian law with respect to the Israeli occupied Palestinian territories, stating in 2016 that "History proves that people will always resist occupation...Palestinian frustration and grievances are growing under the weight of nearly a half-century of occupation. Ignoring this won’t make it disappear. No one can deny that the everyday reality of occupation provokes anger and despair, which are major drivers of violence and extremism and undermine any hope of a negotiated two-state solution."[123]

Former president of the Council Doru Costea, the European Union, Canada, the United States and Britain have at various times accused the UNHRC of focusing disproportionately on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and Israel's occupation of the West Bank.[124][125][126][127]

Speaking at the IDC's Herzliya Conference in Israel in January 2008, Dutch Foreign Minister Maxime Verhagen criticized the actions of the Human Rights Council actions against Israel. "At the United Nations, censuring Israel has become something of a habit, while Hamas's terror is referred to in coded language or not at all. The Netherlands believes the record should be set straight, both in New York and at the Human Rights Council in Geneva", Verhagen said.[128]

In 2008 UNHRC released a statement calling on Israel to stop its military operations in the Gaza Strip and to open the Strip's borders to allow the entry of food, fuel and medicine. UNHRC adopted the resolution by a vote of 30 to 1, with 15 states abstaining.

"Unfortunately, neither this resolution nor the current session addressed the role of both parties. It was regretful that the current draft resolution did not condemn the rocket attacks on Israeli civilians," said Canada's representative Terry Cormier, the lone voter against.[129]

The United States and Israel boycotted the session. U.S. ambassador Warren Tichenor said the Council's unbalanced approach had "squandered its credibility" by failing to address continued rocket attacks against Israel. "Today's actions do nothing to help the Palestinian people, in whose name the supporters of this session claim to act," he said in a statement. "Supporters of a Palestinian state must avoid the kind of inflammatory rhetoric and actions that this session represents, which only stoke tensions and erode the chances for peace", he added.[130] "We believe that this council should deplore the fact that innocent civilians on both sides are suffering", Slovenian Ambassador Andrej Logar said on behalf of the seven EU states on the council.

At a press conference in Geneva on Wednesday, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon responded when asked about its special session on Gaza, that "I appreciate that the council is looking in-depth into this particular situation. And it is rightly doing so. I would also appreciate it if the council will be looking with the same level of attention and urgency at all other matters around the world. There are still many areas where human rights are abused and not properly protected", he said.[131]

Dugard was succeeded in 2008 by Jewish Professor of international law Richard Falk, who has compared Israel's treatment of Palestinians with the Nazis' treatment of Jews during the Holocaust.[132][133][134] After a conflict with the Palestinian Authority's Mahmoud Abbas over his decision, under US pressure, to delay a UNHCR vote on Richard Goldstone's report on violations of international humanitarian law during the 2008-2009 Israel-Gaza war, widely criticized among Palestinians including calls on Abbas to stand down and the PA to be dissolved, Abbas informally asked Falk to resign, accusing him of being among other things "a partisan of Hamas". Falk disputed this and called the reasons given "essentially untrue", with the actual motivation behind his call on Abbas to cease his delaying of the UNHRC vote.[135] The Israeli government announced it would deny Falk a visa to Israel, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip, at least until the September 2008 meeting of the UNHCR.[136][137]

In July 2011, Richard Falk posted a cartoon that critics have described as anti-Semitic onto his blog. The cartoon depicted a bloodthirsty dog with the word "USA" on it wearing a kippah, or Jewish head covering.[138] In response, Falk was heavily criticized by world leaders in the United States, certain European countries and Israel.[138][139][140][141]

At UNHRC's opening session in February 2011, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton criticized the council's "structural bias" against the State of Israel: "The structural bias against Israel – including a standing agenda item for Israel, whereas all other countries are treated under a common item – is wrong. And it undermines the important work we are trying to do together."[142]

In March 2012, the UNHRC was criticized for facilitating an event in the UN Geneva building featuring a Hamas politician. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu castigated the UNHRC's decision stating, "He represents an organization that indiscriminately targets children and grown-ups, and women and men. Innocents – is their special favorite target". Israel's ambassador to the UN Ron Prosor denounced the speech stating that Hamas was an internationally recognized terrorist organization that targeted civilians. "Inviting a Hamas terrorist to lecture to the world about human rights is like asking Charles Manson to run the murder investigation unit at the NYPD", he said.[143]

The United States urged UNHRC in Geneva to stop its anti-Israel bias. It took particular exception to the council's Agenda Item 7, under which at every session, Israel's human rights record is debated. No other country has a dedicated agenda item. The US Ambassador to UNHRC Eileen Chamberlain Donahoe said that the United States was deeply troubled by the "Council's biased and disproportionate focus on Israel." She said that the hypocrisy was further exposed in the Golan Heights resolution that was advocated by the Syrian regime at a time when it was murdering its own citizens.[144]

On 19 June 2018, the United States pulled out of the UNHRC accusing the body of bias against Israel and a failure to hold human rights abusers accountable. Nikki Haley, US Ambassador to the UN, called the organisation a "cesspool of political bias".[145] At UNHRC's 38th Session on 2 July 2018, Western nations de facto boycotted Agenda Item 7 by not speaking to it.[146] Israel had been condemned in 78 resolutions by the Council since its creation in 2006—more resolutions condemning Israel than the rest of the world combined.[147]

Other specific issues

[edit]Indigenous peoples (EMRIP)

[edit]The Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (EMRIP) was established by the Human Rights Council, in 2007, with its mandate amended in September 2016. This body provides the HRC with expert advice on the rights of indigenous peoples, and helps member states to achieve the goals of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.[148]

United States and UNHRC President

[edit]The Council's charter preserves the watchdog's right to appoint special investigators for countries whose human rights records are of particular concern, something many developing states have long opposed. A Council meeting in Geneva in 2007 caused controversy after Cuba and Belarus, both accused of abuses, were removed from a list of nine special mandates. The list, which included North Korea, Cambodia and Sudan, had been carried forward from the defunct Commission.[149] Commenting on Cuba and Belarus, the UN statement said that Ban noted "that not having a Special Rapporteur assigned to a particular country does not absolve that country from its obligations under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights."

The United States said a day before the UN statement that the Council deal raised serious questions about whether the new body could be unbiased. Alejandro Wolff, US Deputy Permanent Representative at the United Nations, accused the council of "a pathological obsession with Israel" and also denounced its action on Cuba and Belarus.[150][151] The UNHRC President Doru Costea said that he agreed with Wolff, saying that the functioning of the Council needed continuous improvement. He added that the Council must examine the behaviour of all parties involved in complex disputes and not place just one state under the magnifying glass.[126][152]

Defamation of religion

[edit]From 1999 to 2011, the CHR and the UNHRC adopted resolutions in opposition to the "defamation of religion".

Climate change

[edit]The Human Rights Council has adopted the Resolution 10/4 about human rights and climate change.[when?][153] At its 48th the Council in Resolution 13 (A/HRC/48/13) recognized the human right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment.[when?][154]

Responses to crises

[edit]2006: Lebanon conflict

[edit]At its Second Special Session in August 2006, the Council announced the establishment of a High-Level Commission of Inquiry charged with probing allegations that Israel systematically targeted and killed Lebanese civilians during the 2006 Israel-Lebanon conflict.[155] The resolution was passed by a vote of 27 in favour to 11 against, with 8 abstentions. Before and after the vote several member states and NGOs objected that by targeting the resolution solely at Israel and failing to address Hezbollah attacks on Israeli civilians, the Council risked damaging its credibility. The members of the Commission of Inquiry, as announced on 1 September 2006, were Clemente Baena Soares of Brazil, Mohamed Chande Othman of Tanzania, and Stelios Perrakis of Greece. The Commission noted that its report on the conflict would be incomplete without fully investigating both sides, but that "the Commission is not entitled, even if it had wished, to construe [its charter] as equally authorizing the investigation of the actions by Hezbollah in Israel", as the Council had explicitly prohibited it from investigating the actions of Hezbollah.[156]

2015: Eritrea

[edit]In June 2015, a 500-page UNHRC report accused Eritrea's government of widespread human rights violations. These were alleged to include extrajudicial executions, torture, indefinitely prolonged national service and forced labour, and widespread sexual harassment, rape and sexual servitude by state officials.[157][158] The Guardian said that the report "catalogues a litany of human rights violations by the 'totalitarian' regime of President Isaias Afwerki 'on a scope and scale seldom witnessed elsewhere'".[157] The report also asserted that these serial violations might amount to crimes against humanity.[157]

The Eritrean Foreign Ministry responded by describing the Commission's report as "wild allegations", "totally unfounded and devoid of all merit", and countercharged the UNHRC with "vile slanders and false accusations".[159]

The vice chairperson of the subcommittee on human rights at the European Parliament said the report detailed "very serious human rights violations", and said that EU funding for development would not continue as at present without change in Eritrea.[160]

August 2018: Myanmar

[edit]In August 2018, the UNHRC released a research report concluding that six generals in Myanmar armed forces should be prosecuted for war crimes as related to the genocide against the Rohingya Muslims.[161] The UNHRC conducted 875 individual interviews as part of this research, confirming that the Myanmar army led a pogrom that claimed the lives of more than 10,000 Rohingyas.[162]

2018–2019: Yemen

[edit]A 2019 report for the UNHRC has said the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia have committed war crimes during the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen.[163][164]

November 2020: Egypt

[edit]The United Nations condemned the November 2020 arrest of three Egyptian human rights advocates of the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR). The activists were charged and detained for having a connection to terror groups. EIPR said the detention was a "clear and co-ordinated response" of their work against human rights violations in the country and the detention of the head of EIPR, Gasser Abdel-Razek, was an attempt to end the human rights work in Egypt.[165]

2022: Russia's invasion of Ukraine

[edit]The United Nations Human Rights Council voted 32–2 on 4 March 2022, with 13 abstentions, to create the International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine, an independent committee of three human rights experts with a mandate to investigate alleged violations of human rights and of international humanitarian law in the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[166][167]

At its eleventh emergency special session, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution, with the required two-thirds majority of voting members, to suspend Russia from the Human Rights Council over reports of gross and systematic violations and abuses of human rights in the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. The measure required a two-thirds majority of the countries present and voting, not counting abstentions. The measure passed with 93 in favor, 24 against and 58 abstentions. After the suspension, Russia's Deputy Permanent Representative, Gennady Kuzmin, announced that Russia had decided to withdraw its Human Rights Council membership altogether.[168] Doing so, Russia restored its rights as an observer to participate in the council's proceedings, while it lost the possibility to have its membership reinstated and to vote or present motions.

November 2022: Iran

[edit]On 24 November 2022, the council held a special session on the deteriorating human rights situation in Iran, in particular with regard to women and children.[169]

April 2024: Israel

[edit]On 5 April 2024, the council held a special session on the deteriorating possible war crimes and crimes against humanity in the Gaza Strip, in particular with regard to genocide in Gaza. The council voted in favour of a halt in all arms sales to Israel.[170] [171]

Candidacy issues

[edit]Syria

[edit]In July 2012, Syria announced that it would seek a UNHRC seat.[172][173] This was while there was serious evidence (provided by numerous human rights organizations including the UN itself) that Syrian President Bashar al-Assad had authorised and funded the slaughter of thousands of civilians, with estimates of 14,000 civilians being killed as of July 2012 during the Syrian civil war.[174][175][176] According to UN Watch, Syria's candidacy was virtually assured under the prevailing election system.[173] Syria would have been responsible for promoting human rights if elected. In response, the United States and European Union drafted a resolution to oppose the move.[177] In the end, Syria was not on the ballot for the 12 November 2012 election to UNHRC.[178]

Sudan and Ethiopia

[edit]In July 2012, it was reported that Sudan and Ethiopia were nominated for a UNHRC seat, despite being accused by human rights organizations of grave human rights violations. UN Watch condemned the move to nominate Sudan, pointing out that Sudan's President Omar Al-Bashir was indicted for genocide by the International Criminal Court. According to UN Watch, Sudan was virtually assured of securing a seat.[179] A joint letter of 18 African and international civil society organizations urged foreign ministers of the African Union to reverse its endorsement of Ethiopia and Sudan for a seat, accusing them of serious human rights violations and listing examples of such violations, and stating that they should not be rewarded with a seat.[180][181] Sudan was not on the ballot for the 12 November 2012 election to UNHRC, but Ethiopia was elected.[178]

Saudi Arabia

[edit]

In September 2015, Faisal bin Hassan Trad, Saudi Arabia's ambassador to the UN in Geneva, was elected Chair of the UNHRC Advisory Committee, the panel that appoints independent experts.[183][184] UN Watch executive director Hillel Neuer said: "It is scandalous that the UN chose a country that has beheaded more people this year [2015] than ISIS to be head of a key human rights panel. Petro-dollars and politics have trumped human rights."[185] Saudi Arabia also shut down criticism, during the UN meeting.[186] In January 2016, Saudi Arabia executed the prominent Shia cleric Sheikh Nimr who had called for free elections in Saudi Arabia.[187]

On 13 October 2020, Saudi Arabia lost its bid to win a seat on the U.N. Human Rights Council. Saudi Arabia and China were competing for membership in a five-way race for four spots with Pakistan, Uzbekistan, and Nepal. China received 139 votes, Uzbekistan 164, Pakistan 169 votes, and Saudi Arabia came in fifth with 90 votes, beaten by Nepal with 150 votes.[188] Human Rights Watch condemned the candidacy filed by China and Saudi Arabia, calling them "two of the world's most abusive governments".[189]

Venezuela

[edit]When the UN General Assembly voted to add Venezuela to the UN Human Rights Council in October 2019, US Ambassador to the United Nations Kelly Craft wrote: "I am personally aggrieved that 105 countries voted in favor of this affront to human life and dignity. It provides ironclad proof that the Human Rights Council is broken, and reinforces why the United States withdrew."[190] Venezuela had been accused of withholding from the Venezuelan people humanitarian aid delivered from other nations, and of manipulating its voters in exchange for food and medical care.[190] The council had been criticized regularly for admitting members who were themselves suspected of human rights violations.[190]

Country positions

[edit]Sri Lanka

[edit]This section contains overly lengthy quotations. (February 2020) |

This section may be too long and excessively detailed. (February 2020) |

Sri Lanka came under increasing scrutiny in early 2012 after a presentation of a draft UNHRC resolution addressing their accountability with regard to their reconciliation activities,[191] a resolution which was subsequently tabled by the United States.[192] The original draft resolution from the United States noted the UNHRC "concern that the LLRC [Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission] report [did] not adequately address serious allegations of violations of international law".[193] The UNHRC resolution then:[193]

- "1. Calls on the Government of Sri Lanka to implement the constructive recommendations in the LLRC report and take all necessary additional steps to fulfill its relevant legal obligations and commitment to initiate credible and independent actions to ensure justice, equity, accountability and reconciliation for all Sri Lankans,

- 2. Requests that the Government of Sri Lanka present a comprehensive action plan as expeditiously as possible detailing the steps the Government has taken and will take to implement the LLRC recommendations and also to address alleged violations of international law,

- 3. Encourages the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and relevant special procedures to provide, and the Government of Sri Lanka to accept, advice and technical assistance on implementing those steps and requests the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights to present a report to the Council on the provision of such assistance at its twenty-second session."

Sri Lankan Ambassador in Geneva Tamara Kunanayakam pointed out that 80% of the UNHRC's funding requirements are supplied by powerful nations such as the United States and its allies. Also, key positions in the UNHRC are mostly held by those who have served in the foreign services of such countries.[194] Sri Lanka's position is that this fact is significantly detrimental to the impartiality of the UNHRC activities, especially when dealing with the developing world. As a result, Sri Lanka, along with Cuba and Pakistan, sponsored a resolution seeking transparency in funding and staffing the UNHRC, during its 19th session starting in February 2012.[194] The resolution was adopted on 4 April 2012.[195]

The original US UNHRC draft resolution that prompted the Sri Lankan, Cuban, and Pakistani transparency initiative was thereafter significantly modified, and passed in 2013. Narayan Lakshman, writing from Washington, D.C. for The Hindu, said the United States "watered down" the resolution,[196][197] while UN Watch described the revised resolution as "toned down".[198] Lakshman noted that "an entire paragraph calling for 'unfettered access'... by a host of external observers and specialists was deleted", and the reworded resolution's demand for international investigation into "alleged human rights violations" was elevated but then "veer[ed] off towards an apparent preference for Sri Lanka to conduct its own internal investigation". He noted that in general "weaker language has been inserted in place of more condemnatory tone".[196] The revised resolution remained entitled "Promoting Reconciliation and Accountability in Sri Lanka" and was assigned UN code "A/HRC/22/L.1/Rev.1".[198] As finally submitted, the U.S. resolution was co-sponsored by 33 countries, including three other members of the U.N. Security council at that time (the UK, France, and Germany), and four other European nations (Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, and Switzerland).[198] By a vote of 25 in favor—which included the resolution sponsors and other EU countries, as well as South Korea—and 13 against, the resolution was adopted on 21 March 2013 (with nine countries abstaining or absent).[198]

United States

[edit]The 43rd U.S. President George W. Bush declared that the United States would not seek a seat on the Council, saying it would be more effective from the outside. He did pledge, however, to support the Council financially. State Department spokesman Sean McCormack said, "We will work closely with partners in the international community to encourage the council to address serious cases of human rights abuse in countries such as Iran, Cuba, Zimbabwe, Burma, Sudan, and North Korea".

The U.S. State Department said on 5 March 2007 that, for the second year in a row, the United States had decided not to seek a seat on the Human Rights Council, asserting the body had lost its credibility with repeated attacks on Israel and a failure to confront other rights abusers.[199] Spokesman Sean McCormack said the council had had a "singular focus" on Israel, while countries such as Cuba, Myanmar and North Korea had been spared scrutiny. He said that though the United States will have only an observer role, it will continue to shine a spotlight on human rights issues. The most senior Republican member of the Committee on Foreign Affairs of the U.S. House of Representatives, Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, supported the administration decision. "Rather than standing as a strong defender of fundamental human rights, the Human Rights Council has faltered as a weak voice subject to gross political manipulation," she said.

Upon passage of UNHRC's June 2007 institution-building package, the U.S. restated its condemnation of bias in the institution's agenda. Spokesman Sean McCormack again criticised the Commission for focusing on Israel in light of many more pressing human rights issues around the world, such as Sudan or Myanmar, and went on to criticise the termination of special rapporteurs to Cuba and Belarus, as well as procedural irregularities that prevented member-states from voting on the issues; a similar critique was issued by the Canadian representative.[200] In September 2007, the US Senate voted to cut off funding to the council.[201]

The United States joined with Australia, Canada, Israel, and three other countries in opposing the UNHRC's draft resolution on working rules citing continuing misplaced focus on Israel at the expense of action against countries with poor human-rights records. The resolution passed 154–7 in a rare vote forced by Israel including the support of France, the United Kingdom, and China, although it is usually approved through consensus. United States Ambassador to the United Nations, Zalmay Khalilzad, spoke about the "council's relentless focus during the year on a single country – Israel," contrasting that with failure "to address serious human rights violations taking place in other countries such as Zimbabwe, DPRK (North Korea), Iran, Belarus and Cuba." Khalilzad said that aside from condemnation of the crackdown of the Burmese anti-government protests, the council's past year was "very bad" and it "had failed to fulfill our hopes".[202]

On 6 June 2008, Human Rights Tribune announced that the United States had withdrawn entirely from the UNHRC,[203] and had withdrawn its observer status.

The United States boycotted the Council during the George W. Bush administration, but reversed its position on it during the Obama administration.[204] Beginning in 2009 however, with the United States taking a leading role in the organization, American commentators began to argue that the UNHRC was becoming increasingly relevant.[205][206]

On 31 March 2009, the administration of Barack Obama announced that it would reverse the country's previous position and would join the UNHRC;[207] New Zealand indicated its willingness not to seek election to the council to make room for the United States to run unopposed, along with Belgium and Norway for the WEOG seats.

On 19 June 2018, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley announced that the United States, under President Donald Trump, was pulling out of the United Nations Human Rights Council, accusing the council being "hypocritical and self-serving"; in the past, Haley had accused it of "chronic anti-Israel bias".[208] "When the Human Rights Council treats Israel worse than North Korea, Iran, and Syria, it is the Council itself that is foolish and unworthy of its name. It is time for the countries who know better to demand changes," Haley said in a statement at the time, pointing to the council's adoption of five resolutions condemning Israel. "The United States continues to evaluate our membership in the Human Rights Council. Our patience is not unlimited."[209]

In December 2020, US Ambassador to the United Nations Kelly Craft said that the UN Human Rights Council was "a haven for despots and dictators, hostile to Israel, and ineffectual on true human rights crises".[210]

On 8 February 2021, following the election of Joe Biden, Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced that the Biden administration would reengage[clarification needed] with the UN Human Rights Council.[211]

On 4 February 2025, President Trump reinstituted his policy and again withdrew from the UN Human Rights Council as part of a larger motion for "ending U.S. support for radical anti-American UN organizations."[212] A White House Fact sheet says the UN Human Rights Council "has demonstrated consistent bias against Israel," and that it “has not fulfilled its purpose and continues to be used as a protective body for countries committing horrific human rights violations."[213]

China

[edit]On 1 April 2020, China joined the United Nations Human Rights Council.[214]

China's Xinjiang policies

[edit]In July 2019, UN ambassadors from 22 nations, including Australia, Britain, Canada, France, Spain, Germany, and Japan, signed a joint letter to the UNHRC condemning China's mistreatment of the Uyghurs and other minority groups, urging the Chinese government to close the Xinjiang internment camps.[215][216]

In response, UN ambassadors from 50 countries including Russia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, UAE, Sudan, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Angola, Algeria, and Myanmar signed a joint letter to the UNHRC praising China's "remarkable achievements in Xinjiang" and opposing the practice of "politicizing human rights issues".[217][215]

In August 2019, Qatar told the UNHRC president that it had decided to withdraw from the response letter.[218] Human rights activists praised Qatar's decision.[219]

In October 2022, 17 countries voted in favor, 19 were against, and 11 abstained in a vote to hold a debate on Xinjiang at its next session, rejecting a Western bid to debate China’s Xinjiang abuses.[220]

Indonesia

[edit]In March 2017, at the 34th regular session of the UN Human Rights Council, Vanuatu made a joint statement on behalf of Tonga, Nauru, Palau, Tuvalu, the Solomon Islands and Marshall Islands raising human rights violations in the Western New Guinea, declared which has been occupied by Indonesia since 1963,[221] and requested that the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights produce a report.[222][223] Indonesia rejected Vanuatu's allegations.[223] Also, a joint NGO statement was made.[224] More than 100,000 Papuans have died during a 50-year Papua conflict.[225]

The UNHRC expressed grave concern over ongoing human rights violations against the Papuan people in Indonesia, citing a lack of accountability and transparency in investigations, hindering reparations for victims. Recommendations were made to intensify efforts to combat impunity and prioritize investigations and reparations for victims.[226]

Israel

[edit]On 6 February 2025, following the United States’ decision to withdraw, Israeli Foreign Minister Gideon Saar announced the withdrawal of Israel from the UN Human Rights Council.[227]

Criticism

[edit]The United States opposed the creation of the UNHRC during the George W. Bush administration to protest the repressive states among its membership.[204][228] In March 2009 the Obama administration reversed that position and decided to "reengage" and seek a seat on the UNHRC.[204] With the United States taking a leading role in the organization, American commentators began to argue that the UNHRC was becoming increasingly relevant.[205][206]

The UNHRC has been criticised for the repressive states among its membership.[204] Countries with questionable human rights records that have served on the UNHRC include Pakistan, Cuba, Saudi Arabia, China, Indonesia, and Russia.[229][230]

On 12 October 2021, the Human Rights Watch criticised UNHRC elections and stated that UN member countries should refrain from voting for Cameroon, Eritrea, United Arab Emirates, and other candidates as they hold abysmal rights records. These countries were alleged not to meet the qualifications for membership on the board. The UN director at Human Rights Watch, Louis Charbonneau said that electing such serious rights abusers sends a terrible message that the UN member states do not take the council's fundamental mission to protect human rights seriously.[231]

Bloc voting

[edit]A Reuters report in 2008 said that independent human rights groups say that UNHRC is being controlled by some Middle East and African nations, supported by China, Russia and Cuba, which protect each other from criticism.[232] This drew criticism from the UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon at the ineffectiveness of UNHRC, saying it had fallen short of its obligations. He urged countries to "drop rhetoric" and rise above "partisan posturing and regional divides"[233] and get on with defending people around the world.[232]

Of the 53 countries which defended China's imposition of the Hong Kong National Security Law following the 2019–2020 Hong Kong protests, at least 43 were participants in the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative, with one Axios reporter noting that "Beijing has effectively leveraged the UN Human Rights Council to endorse the very activities it was created to oppose."[234]

Ban Ki-moon also appealed for the United States to fully join the council and play a more active role.[233]

The UNHRC was criticized in 2009 for adopting a resolution submitted by Sri Lanka praising its conduct in Vanni that year, ignoring pleas for an international war crimes investigation.[235]

Accountability programme

[edit]On 18 June 2007, one year after holding its first meeting, the UNHRC adopted its Institution-building package, to guide it in its future work. Among its elements was the Universal Periodic Review, which assesses the human rights situations in all 193 UN member states. Another element is an Advisory Committee, which serves as the UNHRC's think tank and provides it with expertise and advice on thematic human rights issues. A further element is a Complaint procedure, which allows individuals and organizations to bring complaints about human rights violations to the attention of the council.

See also

[edit]- OIC § Human rights

- Community of Democracies

- Human rights in cyberspace

- United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights

- UN Watch

- Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action

Notes

[edit]- ^ French: Conseil des droits de l'homme des Nations unies,[1] CDH

- ^ For war crimes, see "UN Adopts Resolution on Sri Lanka War Crimes Probe". BBC News. 22 March 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2012. For intervention against nationwide human rights abuses, see

- Human Rights Watch (25 March 2011). "UN: Rights Body Acts Decisively on Iran, Cote d'Ivoire". Retrieved 2 June 2012.,

- ISHR. "Human Right Council follows up to special sessions on Cote-d'Ivoire and Libya". Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2012.,

- "Côte d'Ivoire: UN Human Rights Council strongly condemns post-electoral abuses". 23 December 2010. Retrieved 2 June 2012.,

- "UN calls for investigation into Houla killings in Syria". BBC News. June 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2012.,

- Human Rights Watch (21 June 2010). "UN: Rights Council Condemns Violations in Kyrgyzstan". Retrieved 2 June 2012.,

- ISHR. "Human Rights Council follows up to special sessions on Cote d'Ivoire & Libya". Archived from the original on 6 June 2011.,

- Human Rights Watch (26 March 2010). "UN Human Rights Council: Positive Action on Burma, Guinea, North Korea". Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ by resolution A/RES/60/251

- ^ Membership suspended from the Council by UN General Assembly Resolution ES-11/3 following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.

- ^ Now as the Republic of North Macedonia

References

[edit]- ^ "Conseil des droits de l'homme". 9 March 2019. Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ "About the Human Rights Council". Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Archived from the original on 11 March 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ^ "OHCHR | HRC Sessions". www.ohchr.org. Archived from the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ "Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association". Archived from the original on 3 June 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ "HRC Freedom of Opinion and Expression Resolution". Archived from the original on 3 July 2010. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ "USCIRF Welcomes Move Away from 'Defamation of Religions' concept". Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ UNOG. "Human Rights Council Establishes Working Group On Discrimination Against Women in Law And Practise". Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ "Council establishes mandate on Côte d'Ivoire, adopts protocol to child rights treaty, requests study on discrimination and sexual orientation". 17 June 2011. Archived from the original on 24 June 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2013. and "UN publishes first global report and recommendations to tackle gay rights abuses". 16 December 2011. Archived from the original on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ "UN creates new human rights body". BBC. 15 March 2006. Archived from the original on 26 December 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- ^ Gladstone, Rick (14 October 2021). "U.S. Regains Seat at U.N. Human Rights Council, 3 Years After Quitting". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ Piccone, Ted (25 February 2021). "UN Human Rights Council: As the US returns, it will have to deal with China and its friends". Brookings. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ a b c "HRC Membership of the Human Rights Council". www.ohchr.org. OHCHR. Archived from the original on 27 May 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ "CHR Membership and Bureau". www.ohchr.org. United Nations Human Rights Council. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ "United Nations Human Rights Council, Sessions". Archived from the original on 20 May 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ a b "HRC Sessions". www.ohchr.org. OHCHR. Archived from the original on 27 May 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ "Membership of the Human Rights Council". United Nations Human Rights Council. United Nations. 26 February 2019. Archived from the original on 13 February 2019. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ "What is the U.N. Human Rights Council, from which Trump has withdrawn?". Archived from the original on 4 February 2025. Retrieved 4 February 2025.

- ^ "UN Human Rights Council Elections for 2025-2027 and the Responsibility to Protect". Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect. 9 October 2024. Retrieved 2 January 2025.

- ^ "Election of the Human Rights Council". United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

- ^ "Election of the Human Rights Council (11 October 2022)". United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. 17 October 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "Election of the Human Rights Council (14 October 2021)". United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. 14 October 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ "Election of the Human Rights Council (13 October 2020)". United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. 13 October 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ "Election of the Human Rights Council (17 October 2019)". United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. 17 October 2019. Archived from the original on 17 October 2019. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ^ "Election of the Human Rights Council (12 October 2018)". United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. 12 October 2018. Archived from the original on 25 November 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ "Election of the Human Rights Council (16 October 2017)". United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. 16 October 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ "Election of the Human Rights Council (28 October 2016)". United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. 28 October 2016. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ^ "Election of the Human Rights Council (28 October 2015)". United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. 28 October 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ "Election of the Human Rights Council (21 October 2014)". United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. 21 October 2014. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ "Election of the Human Rights Council (12 November 2013)". United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. 12 November 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ "Election of the Human Rights Council (12 November 2012)". United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. 12 November 2012. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ "Election of the Human Rights Council (20 May 2011)". United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. 20 May 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ "Election of the Human Rights Council (13 May 2010)". United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. 13 May 2010. Archived from the original on 26 July 2010. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ "Election of the Human Rights Council (12 May 2009)". United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. 12 May 2009. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ "Election of the Human Rights Council (21 May 2008)". United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. 21 May 2008. Archived from the original on 14 November 2008. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ "Election of the Human Rights Council (17 May 2007)". United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. 17 May 2007. Archived from the original on 10 January 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ a b c "General Assembly Elects 47 Members of New Human Rights Council; Marks 'New Beginning' for Human Rights Promotion, Protection". United Nations General Assembly. United Nations. 12 October 2018. Archived from the original on 21 September 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ "Human Rights Council elects Jürg Lauber of Switzerland as its President for 2025". ohchr.org. 9 December 2024. Retrieved 2 January 2025.

- ^ "Human Rights Council elects Václav Bálek of the Czech Republic as its President for 2023". UN OHCR. UN. 9 December 2022. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "Human Rights Council elects Federico Villegas of Argentina as its president for 2022". UN OHCR. UN. 6 December 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ Farge, Emma (15 January 2021). "Fiji wins presidency of U.N. rights body after vote unblocks leadership impasse". msn.com. Reuters. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ "President of the 14th Cycle". Archived from the original on 21 June 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ The Human Rights Council elects Ambassador Ambassador Choi Kyong-lim of the Republic of Korea as its new President. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ Section, United Nations News Service (10 December 2012). "UN News – UN Human Rights Council: new President will help promote human rights equitably". UN News Service Section.

- ^ a b "Human Rights Council – Membership of the Human Rights Council". .ohchr.org. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ "Resolution adopted by the General Assembly - 60/251. Human Rights Council" (PDF). OHCHR. 3 April 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ "UN General Assembly Resolution 60/251.8" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 June 2010. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ a b Ghandhi, P. R.; Ghandhi, Sandy, eds. (2012). "Resolution adopted by the General Assembly 60/251: Human Rights Council (2006)". Blackstone's International Human Rights Documents. OUP Oxford. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-19-965632-5.

- ^ "General Assembly Suspends Libya from Human Rights Council". United Nations: Meetings Coverage and Press Releases. 1 March 2011.

- ^ "Member States vote to reinstate Libya as member of UN Human Rights Council". United Nations: UN News. 18 November 2011.

- ^ "UN suspends Russia from Human Rights Council". CNN. 7 April 2022. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ Lederer, Edith M.; Peltz, Jennifer (7 April 2022). "UN assembly suspends Russia from top human rights body". AP News. Associated Press. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ Al Jazeera and news agencies (7 April 2022). "UN suspends Russia from human rights body over Ukraine abuses". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ "The Universal Periodic Review Mechanism". Human Rights Watch. 27 June 2006. Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- ^ Main points: What is the UPR Archived 24 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 31 January 2016

- ^ More details on: Information note for NGOs regarding the Universal Periodic Review mechanism (as of second cycle) Archived 24 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 31 January 2016

- ^ For complete calendar, see: Human Rights Council Universal Periodic Review

- ^ For complete calendar, see: Human Rights Council 2nd Universal Periodic Review Archived 12 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ For complete calendar, see: Human Rights Council 3rd Universal Periodic Review Archived 27 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Paragraph 16 of General Assembly Resolution 60/251 of 15 March 2006

- ^ See: Resolution 12/1 of 1 October 2009, included in UN document A/65/53, containing the Report of the Human Rights Council on its Twelfth Session (14 September – 2 October 2009) Archived 24 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Resolution 16/21" (PDF). upr-info.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ Nations, United. "Member States | United Nations". United Nations. Archived from the original on 4 May 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ Lars Müller, (ed.), The First 365 days of the United Nations Human Rights Council, p. 81 and ff.

- ^ a b "Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights". Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. n.d. Archived from the original on 31 December 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2009.

- ^ "Report of the Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of human rights on its fifty-eighth session". A/HRC/2/2. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. 9 November 2006. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2009.

- ^ "Human Rights Council Advisory Committee". UN Human Rights Council. n.d. Retrieved 11 August 2009.

- ^ Human Rights Council Advisory Committee Concludes Third Session Human Rights Council Advisory Committee Roundup 7 August 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Resolution 5/1". United Nations Digital Library System. 23 June 1949. Archived from the original on 13 February 2020.

- ^ "Complaint Procedure of the Human Rights Council". United Nations Digital Library System. 4 March 2008. Archived from the original on 19 February 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ "Human Rights Activism and the Role of NGOs - Manual for Human Rights Education with Young people - www.coe.int". Manual for Human Rights Education with Young people. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ^ "Frequently asked questions". United Nations Human Rights Council.

- ^ "Human Rights Council Complaint Procedure | A Conscientious Objector's Guide to the International Human Rights System". co-guide.org. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ^ "Grievance Redress Service". World Bank. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ^ "Human Rights Council Complaint Procedure". United Nations Human Rights Council.

- ^ King, David; Wheeler, Sue (18 March 2001). Supervising Counsellors: Issues of Responsibility. SAGE. ISBN 978-0-7619-6408-7.

- ^ a b c d McBeth, Nolan and Rice The International Law of Human Rights (OUP, 2011) at 231

- ^ Moeckli, Shah, Sivakumaran, Harris International Human Rights Law 2nd ed (OUP, 2014) at 371

- ^ Mirzoev, Tolib; Kane, Sumit (16 April 2018). "Key strategies to improve systems for managing patient complaints within health facilities – what can we learn from the existing literature?". Global Health Action. 11 (1): 1458938. doi:10.1080/16549716.2018.1458938. ISSN 1654-9716. PMC 5912438. PMID 29658393.

- ^ "Forum on Minority Issues". .ohchr.org. Archived from the original on 2 July 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ "Social Forum". Ohchr.org. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ Khabook, Reza (8 June 2023). "Iran's Appointment as the Chair-Rapporteur of the UNHRC Social Forum: Politicisation of Subsidiary Expert UN Human Rights Bodies". Völkerrechtsblog. doi:10.17176/20230608-110936-0.

- ^ Farge, Emma (2 November 2023). "Iran's appointment to chair UN rights meeting draws condemnation". Reuters. Retrieved 4 November 2023.

- ^ "History of the United Nations Special Procedures Mechanism". Universal Rights Group. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch