Folk saint

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2025) |

Folk saints are dead people or other spiritually powerful entities (such as indigenous spirits) venerated as saints, but not officially canonized. Since they are saints of the "folk", or the populus, they are also called popular saints. Like officially recognized saints, folk saints are considered intercessors with God, but many are also understood to act directly in the lives of their devotees.

Frequently, their actions in life, as well as in death, distinguish folk saints from their canonized counterparts: official doctrine would consider many of them sinners and false idols. Their ranks are filled by folk healers, indigenous spirits, and folk heroes. Folk saints occur throughout the Catholic world, and they are especially popular in Latin America, where most have small followings; a few are celebrated at the national or even international level.

Origins

[edit]In the pre-Christian Abrahamic tradition, the prophets and holy people who were honored with shrines were identified by popular acclaim rather than official designation. In fact, the Islamic counterparts of the Christian saints, associated most closely with Sufism, are still identified this way.[1] Early Christians followed in the same tradition when they visited the shrines of martyrs to ask for intercession with God.

Thus, there is a long tradition for the veneration of unofficial saints, and modern folk saints continue to reach popularity in much the same way as ever. Tales of miracles or good works performed during the person's life are spread by word of mouth, and, according to anthropologist Octavio Ignacio Romano, "if exceptional fame is achieved, it may happen that after his [or her] death the same cycle of stories told during life will continue to be repeated."[2] Popularity is likely to increase if new miracles continue to be reported after death. Hispanic studies professor Frank Graziano explains:

[M]any folk devotions begin through the clouding of the distinction between praying for and praying to a recently deceased person. If several family members and friends pray at someone's tomb, perhaps lighting candles and leaving offerings, their actions arouse the curiosity of others. Some give it a try—the for and the to begin intermingling—because the frequent visits to the tomb suggest that the soul of its occupant may be miraculous. As soon as miracles are announced, often by family members and friends, newcomers arrive to send up prayers, now to the miraculous soul, with the hope of having their requests granted.[3]

This initial rise to fame follows much the same trajectory as that of the official saints. Professor of Spanish Kathleen Ann Myers writes that Rose of Lima, the first canonized American saint, attracted "mass veneration beginning almost at the moment of the mystic's death." Crowds of people appeared at her funeral, where some even cut off pieces of her clothing to keep as relics. A lay religious movement quickly developed with Rosa de Lima at the center but she was not officially canonized until half of a century later.[4] In the meantime, she was essentially a folk saint.

As the Church spread, it became more influential in regions that celebrated deities and heroes that were not part of Catholic tradition. Many of those figures were incorporated into a local variety of Catholicism: the ranks of official saints then came to include a number of non-Catholics or even fictional persons. Church leaders made an effort in 1969 to purge such figures from the official list of saints, though at least some probably remain. Many folk saints have their origins in this same mixing of Catholic traditions and local cultural and religious traditions. To distinguish canonized saints from folk saints, the latter are sometimes called animas or "spirits" instead of saints.

Local character

[edit]Folk saints tend to come from the same communities as their followers. In death, they are said to continue as active members of their communities, remaining embedded within a system of reciprocity that reaches beyond the grave. Devotees offer prayers to the folk saints and present them with offerings, and folk saints repay the favors by dispensing small miracles. Many folk saints inhabit marginalized communities, the needs of which are more worldly than others; they therefore frequently act in a more worldly, more pragmatic, less dogmatic fashion than their official counterparts.[5] Devotion to folk saints, then, frequently takes on a distinctly local character, a result of the syncretic mixing of traditions and the particular needs of the community.

The contrast between the manner in which Latin American and European folk saints are said to intercede in the lives of their followers provides a good illustration. In Western Europe, writes anthropologist and religious historian William A. Christian, "the more pervasive influence of scientific medicine, the comparative stability of Western European governments and above all, the more effective presence of the institutional Church" have meant that unofficial holy people generally work within established doctrine. Latin American holy persons, on the other hand, often stray much further from official canon. Whereas European folk saints serve merely as messengers of the divine, their Latin American counterparts frequently act directly in the lives of their devotees.[6]

During the Counter-Reformation in Europe, the Council of Trent released a decree "On the Invocation, Veneration, and Relics, of Saints, and on Sacred Images", which explained that, in Roman Catholic doctrine, images and relics of the saints are to be used by worshipers to help them contemplate the saints and the virtues that they represent but that those images and relics do not actually embody the saints. In the same way, folk saints in Europe are seen as intermediaries between penitents and the divine but are not considered powerful in and of themselves. A shrine may be built "that becomes the location for the fulfillment of the village's calendrical obligations and critical supplications to the shrine image—the village's divine protector," Christian writes, but "in this context the shrine image and the site of its location are of prime importance; the seer merely introduces it, and is not himself or herself the focal point of the worship."[7]

In pre-Columbian Mesoamerican tradition, on the other hand, representation meant embodiment of these holy figures rather than mere resemblance, as it did in Europe.[8] Thus, pre-Hispanic Mexican and Central American images were understood to actually take on the character and spirit of the deities they represented, a perspective that was considered idolatry by European Catholics. As the inheritors of this tradition, folk saints of the region often are seen to act directly in the lives of their devotees rather than serving as mere intermediaries, and they are themselves venerated. Visitors frequently treat the representations of folk saints as real people, observing proper etiquette for speaking to a socially superior person or to a friend depending on the spirit's disposition—shaking hands, or offering it a cigarette or a drink.

The popularity of a particular folk saint also depends on the changing dynamics and needs of the community over time. The popular devotion to Yevgeny Rodionov provides an example. Rodionov was a Russian soldier who was killed by rebels in Chechnya after he reportedly refused to renounce his religion or remove a cross he wore around his neck. He is not recognized by the Russian Orthodox Church as an official saint; yet, within a few years of his death, he had gained a popular following: his image appeared in homes and churches around Russia, his hometown started drawing pilgrims, and he began to receive prayers and requests for intercession. Rodionov became a favorite folk saint for soldiers and came to represent Russian nationalism at a time of conflict when the country was still reeling from the dissolution of the Soviet Union. As one journalist observed in 2003, his death and transition into the role of a folk saint served "to fill a nationalist hunger for popular heroes" when heroes were sorely needed.[9]

Devotions

[edit]A devotee might visit the shrine of a folk saint for any number of reasons, including general requests for good health and good luck, the lifting of a curse, or protection on the road, but most folk saints have specialties for which their help is sought. Difunta Correa, for example, specializes in helping her followers acquire new homes and businesses. Juan Bautista Morillo helps gamblers in Venezuela,[citation needed] and Juan Soldado watches over border crossings between Mexico and the United States.[10] This practice is not so different from that of canonized saints—St. Benedict, for example, is the patron saint of agricultural workers—but it would be hard to find a canonized saint to look after narcotics traffickers, as does Jesús Malverde. In fact, a number of folk saints attract devotees precisely because they respond to requests that the official saints are unlikely to answer. As Griffith writes, "One needs ask for help where the help is likely to be effective."[11] So long as followers come before them with faith and perform the proper devotions, some folk saints are as willing to place a curse on a person as to lift one.[citation needed]

An offering to a folk saint might include the same votive candles and ex-votos (tributes of thanks) left at the shrines to canonized saints, but they also frequently include other items that reflect something of the spirit's former life or personality. Thus, Difunta Correa, who died of thirst, is given bottles of water; Maximón and the spirit of Pancho Villa are both offered cigarettes and alcohol; teddy bears and toys are left at the tomb of a little boy called Carlitos in a cemetery in Hermosillo, Mexico. Likewise, prayers to folk saints are often paired with or incorporate aspects of the Rosary but (as with many canonized saints) special petitions have been composed for many of them, each prayer evoking the particular characteristics of the saint being addressed. Other local or regional idiosyncrasies also creep in. In parts of Mexico and Central America, for example, the aromatic resin copal is burned for the more syncretic spirits like Maximón, a practice that has its roots in the offerings made to indigenous deities.

As long as the spirits come through for their followers, devotees will return. Word of mouth spreads news of cures and good fortune, and particularly responsive spirits are likely to gain a large following. Not all remain popular however, as in the case of Cutubilla whose cult has long since died out. While official saints remain canonized regardless of their popularity, folk saints that lose their devotees through their failure to respond to petitions might fade from memory entirely.

Many folk saints are venerated exclusively in private homes by their devotees. For some devotion merely consists in the veneration of images or statues and the dissemination of prints or holy cards with the saint's image. This is because a folk saint may not have a special public shrine of their own and they are not represented by the institutional Church. Instead devotees usually erect small altars in their houses decorated with images of the saint, candles, flowers and other items. They also place holy cards in their cars or in their pockets to express their devotion and through distributing holy cards. Imagery plays an essential part in the establishing of a folk saint's cult[12] and the maintenance of that devotion.

Relationship with the Catholic Church

[edit]In areas where the Catholic Church has greater power, it maintains more control over the devotional lives of its members. Thus, in Europe, folk devotions that are encouraged by the Church are quickly institutionalized, while those that are discouraged usually die out or continue only at reduced levels.[13] For similar reasons, folk saints are more often venerated in poor and marginalized communities than in affluent ones. Nor are folk saints found in shrines to the canonical saints, though the reverse is often true: it is not uncommon for a folk saint's shrine to be decorated with images of other folk saints as well as members of the official Catholic communion. Shrines in the home, too, frequently include official and unofficial saints together. Graziano explains:

Catholicism is not so much abandoned as expanded [by folk practitioners]; it is stretched to encompass exceptional resources. Whereas Catholicism ... defends a distinction between canonical and non-canonical or orthodox and heterodox, folk devotion intermingles these quite naturally and without reserve.[14]

Nonetheless, Catholics are generally discouraged from cultivating a devotion to folk saints (owing to a lack of certainty that the said person is in heaven or not or if doubt remains as to whether the person ever existed). In contrast, other folk saints such as San la Muerte and Santa Muerte are outright condemned by the Catholic Church as being evil and abominable.[15]

List of folk saints by country

[edit]| Picture | Name | Died | Countries of Devotion | Shrine | Patronage | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constantina of Rome | 354 | Santa Costanza, Via Nomentana, Rome, Italy | Maidens, sick people, people who want to convert to Catholicism | Eldest daughter of Constantine I, whose conversion took place after allegedly directing prayers to Saint Agnes and being cured | |

| Lewina | 7th century | St. Leonard's Church, Seaford, East Sussex, England | The persecuted, the oppressed, those who suffer unjustly, Seaford, England | Romano-British virgin put to death by Saxon invaders | ||

| Mabyn | 650 | St Mabyn Parish Church, St Mabyn, Cornwall, England | Agriculture, farmers, harvests, protector of livestock, St Mabyn | Daughter of King Brychan, sister of Saint Nectan | |

| Eadburh of Bicester | 650 | Bicester Priory, Bicester, Oxfordshire, England | Women's rights, women's education, female empowerment | 7th century Old English nun, abbess, daughter of King Penda of Mercia | |

| Veronus of Lembeek | 863 | Church of Saint Veronus, Lembeek, Belgium | Headaches, typhus, rheumatism, fever, contagious diseases, ulcers, beer and Lembeek | Son of Louis the German and twin brother of Verona of Leefdaal | ||

| Verona of Leefdaal | 870 | Chapel of Saint Verona, Leefdaal, Belgium | Fever | Daughter of Louis the German and twin sister of Veronus of Lembeek | ||

| Wigbert | 747 | Wigbertikirche, Ohrdruf, Germany | Missionaries, farmers, gardeners, Thuringia, Ohrdruf, Bad Hersfeld | Anglo-Saxon Benedictine monk, missionary, disciple of Saint Boniface | |

| Alberic of Utrecht | 784 | Dom Church, Utrecht, Netherlands | Benedictine monk, bishop of Utrecht | |||

| Ida of Lorraine | 1113 | Church of Saint Ida, Bouillon, Belgium | Protection of women and children, and those seeking charity, and generosity | Wife of Count Eustace II, mother of Eustace III of Boulogne, Godfrey of Bouillon and King Baldwin; founded several monasteries in Northern France in later life | |

| Henry of Coquet (known as Saint Henry the Dane) | 1127 | Coquet Island, Northumberland, England | Danish hermit who lived in a hermitage on Coquet Island | |||

| William of Norwich | 1144 | Norwich Cathedral, Norwich, England | Adopted children, the falsely accused, torture victims, Norwich | English boy whose disappearance and killing was blamed on the Jews | |

| David I King of Scots | 1153 | Dunfermline Abbey, Dunfermline, Scotland | The arts, the environment, Kelso Abbey, Dunfermline Abbey, Scotland | 26th king of Alba, prince of the Cumbrians; founded several monasteries in Scotland | |

| Harold of Gloucester | 1168 | Gloucester Cathedral, Gloucester, England | Kidnapped children, torture victims | English boy whose murder was allegedly motivated by the blood libel | ||

| Godric | 1170 | Finchale Priory, County Durham, England | Fishermen, sailors, Durham | English hermit, sailor, merchant, and centenarian | |

| Niels of Aarhus | 1180 | Aarhus Cathedral, Aarhus, Denmark | Danish prince who lived an ascetic life; cult extinct by the 18th century | |||

| Robert of Bury | 1181 | Bury St Edmunds Abbey, Bury, Suffolk, England | English boy who was allegedly kidnapped and ritually murdered by Jews on Good Friday; cult suppressed in 1536 | ||

| Anders of Slagelse (known as Hellig Anders) | late 12th century | Saint Peter's Church, Slagelse, Denmark | The arts, Slagelse | 12th century parish priest from Slagelse | |

| Robert Flower (known as Robert of Knaresborough) | 1218 | St Robert's Cave and Chapel of the Holy Cross, Knaresborough, England | Outcasts, misfits, Knaresborough | 12th century English hermit who lived in a cave | |

| Guðmundur Arason | 1237 | Hólar Cathedral, Hólar, Iceland | Iceland, Icelanders | 12th century bishop of Hólar | |

| Theobald of Marly | 1247 | Vaux-de-Cernay Abbey, Cernay-la-Ville, France | Farmers, protection against bad weather and crop failure, eye disease, Oblates of Mary Immaculate | 13th century French knight, Cistercian monk, and abbot | |

| Dominic del Val (known as Dominguito) | 1250 | Dominguito del Val Chapel, Zaragoza Cathedral, Zaragoza, Spain | Altar boys, acolytes, choirboys | Aragonese choirboy allegedly murdered in a blood libel; the veracity of the story of his murder is disputed. | |

| Hugh of Lincoln (known as Little Hugh of Lincoln) | 1255 | Lincoln Cathedral, Lincoln, England | English boy allegedly murdered in a blood libel | ||

| Guglielma (known as Wilhelmina of Bohemia) | 1279 or 1282 | The Guglielmites | Italian noblewoman; self-alleged daughter of King Ottokar I; preached a feminized version of Christianity, founded the Guglielmites who worshipped her as the Holy Spirit incarnate; cult was suppressed in 1300 | |||

| John Schorne | 1313 | Schorne Well, North Marston, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom | Gout and toothache | English priest from North Marston who became renowned for his piety and miraculous cures for gout and toothache[16] | |

| Richard Rolle | 1349 | Church of the Holy Trinity, Hampole, South Yorkshire, England | Spiritual writers, mysticism | English hermit, mystic, and religious writer | |

| Girolamo Savonarola | 1498 | Against persecution | Dominican friar and reformer killed for heresy in the period of the Renaissance Florence | ||

| Potenciana | 16th century | Church of All Saints, Villanueva de la Reina, Spain | 16th century Spanish Anchoress | ||

| Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros | 1517 | Toledo Cathedral, Toledo | Dakhla, Western Sahara, students, scholors, educators. | Spanish Cardinal, theologian, Archbishop of Toledo, and Primate of Spain; helped preserve the Mozarabic Rite from extinction | |

| Catherine of Aragon | 1536 | Peterborough Cathedral, Peterborough, England | First wife of King Henry VIII; mother of Queen Mary I of England | ||

| Amakusa Shirō | 1638 | Japanese Catholic samurai and revolutionary | |||

| King Charles the Martyr | 1649 | St George's Chapel, Windsor, United Kingdom | 24th King of England (1625–1649), head of the House of Stuart. martyr of the English Civil War | ||

| Simón Bolívar (known as "El Libertador") | 1830 | National Pantheon of Venezuela,Caracas, Venezuela | Bolivarianism | Venezuelan statesman and military officer who led what are currently the countries of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama, and Bolivia to independence from the Spanish Empire. | |

| Apolinario de la Cruz (known as Hermano Pule) | 1841 | Tayabas, Quezon, Philippines | Cofradía de San José, religious freedom, peace, native Filipinos | Filipino religious leader and revolutionary | ||

| Stephen 'Stoney' Brennan | 1845 | Westbridge Street Loughrea, Co Galway | Invoked by women seeking husbands and for those seeking cures for illnesses/ailments. (People kiss his head carving) [17][18] | A poor Irish man hanged for stealing a turnip in 1845. Nothing else is known about him except that he was ''the seventh son of a seventh son'' and believed to be a healer. | ||

| Jean Marie Villars | 1868 | Holy Cross Cemetery, Indianapolis, Indiana | financial problems, good health, fortune, finding lost things, murder victims | French-American priest in Indiana who died under mysterious circumstances | |

| Marie Laveau | 1881 | United States | Marie Laveau's tomb, New Orleans, Louisiana | Invoked by Herbalists, mid-wives, Spiritualists, diviners, and Wangateurs, for love, luck, health, and general blessings. | A Louisiana Creole freed-woman, business owner, hair dresser and Voodoo Priestess in New Orleans. | |

| Héléna Soutadé | 1885 | Terre-Cabade Cemetery, Toulouse, France | children | French teacher and mystic | ||

| María Adelaide de Sam José e Sousa (known as Saint Maria Adelaide) | 1885 | Saint Maria Adelaide Chapel, Arcozelo, Portugal | Portuguese woman with incorruptible body[19] | ||

| Pancho Sierra | 1891 | Salto Cemetery, Buenos Aires, Argentina | Argentine faith healer | ||

| José Rizal | 1896 | Iglesia Sagrada ni Lahi, Dapitan, Zamboanga del Norte, Philippines | Rizalista religious movements | Filipino nationalist and polymath during the end of the Spanish colonial period of the Philippines. | |

| José Tomás de Sousa Martins | 1897 | Campo dos Mártires da Pátria, Lisbon, Portugal | Portuguese physician and philanthropist | ||

| Francesc Canals i Ambrós (known as El Santet) | 1899 | Poblenou Cemetery, Barcelona | Marriage, fertility, non-monetary favors. | Catalan youth and miracle worker | |

| Teresa Urrea (known as Santa Teresa de Cabora) | 1906 | Chapel of Saint Teresa, San Pedro, Arizona, United States | soldiers, government, healing, Yaqui people, Mayo people, uprising, homeless, sick, revolution | Mexican mystic, folk healer, and revolutionary insurgent | ||

| Don Pedro Jaramillo | 1907 | Don Pedro Jaramillo Shrine, Falfurrias, Texas, United States | cures, good health, fortune, healing, protection from diseases | Mexican-American curandero, faith healer, and clairvoyant | |

| Maria Izilda de Castro Ribeiro (known as Menina Izildinha, Angel of the Lord) | 1911 | Mausoleum of Menina Izildinha, Monte Alto, São Paulo, Brazil | Children, adolescents, orphans, good health, social welfare, protection from harm, protection from diseases, people in poverty | Portuguese girl who died of leukemia | |

| Grigori Rasputin | 1916 | Russian mystic and self-proclaimed holy man | |||

| José Doroteo Arango Arámbula (known as Francisco "Pancho" Villa) | 1923 | Monumento a la Revolución, Mexico City, Mexico | Mexican revolutionary general and politician | ||

| Engelbert Dollfuss | 1934 | Dollfusskirche, Hohe Wand, Austria | Austria | Former Chancellor of Austria, leader of the Vaterländische Front; murdered by the Schutzstaffel during the July Putsch | |

| José Antonio Primo de Rivera | 1936 | Valley of the Fallen, Sierra de Guadarrama, Spain | Spaniards, falangists, workers. | Spanish politician, founder of Falange Española, and nationalist martyr. | |

| Filomena Almarines | 1938 | St. Filomena Chapel, St.Filomena cemetery, Biñan, Laguna, Philippines | Filipino Incorrupt folk saint | |||

| Juan Castillo Morales (known as Juan Soldado) | 1938 | Shrine of San Juan Soldado, Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico | good health, criminals, family problems, crossing the U.S.–Mexico border | Mexican convicted rapist and murderer turned folk saint | |

| José de Jesús Fidencio Síntora (known as Niño Fidencio) | 1938 | Fidencista Christian Church, Espinazo, Nuevo León, Mexico | healings, cures, protection from diseases | Mexican curandero | ||

| Corneliu Zelea Codreanu | 1938 | Green House, Bucharest, Romania | Romanians | Founder of the Legion of the Archangel Michael later known as the Iron Guard, nationalist martyr; | ||

| Sara Colonia Zambrano (known as Sarita Colonia) | 1940 | Capilla de Santa Sarita, Callao, Peru | bus and taxi drivers, prostitutes, LGBT community, job seekers, poor, migrants | Peruvian girl credited with the ability to make miracles | |

| Juan Bautista Bairoletto | 1941 | immigrants, prostitutes, bandits, financial problems, justice | Argentine outlaw dubbed as El Robin Hood criollo | ||

| Eva Perón | 1952 | Casa Museo Eva Perón, Los Toldos, Argentina | First Lady of Argentina (1946–1952) | ||

| Valeriu Gafencu | 1952 | Târgu Ocna, Bacău, Romania | Romanian Orthodox theologian and martyr | |||

| Joseph Stalin[20] | 1953 | Kremlin Wall Necropolis, Moscow, Russia | Victory, patriotism, communism | Leader of the USSR from 1922 to 1953; venerated by some priests of the Russian Orthodox Church | |

| Miguel Ángel Gaitán (known as El Angelito Milagroso) | 1967 | Banda Florida, San Juan, Argentina | Argentine baby who died in meningitis | |||

| Che Guevara | 1967 | Che Guevara Mausoleum, Santa Clara, Cuba | Warfare, government, revolution | Argentine Marxist revolutionary, physician, author, guerrilla, leader, diplomat, and military theorist. | |

| Hồ Chí Minh[citation needed] | 1969 | Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum, Hanoi, Vietnam | 1st President of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (1945–1969), communist revolutionary, marxist theorist, Vietnamese politician | ||

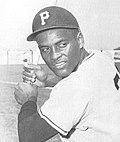

| Roberto Clemente[21] | 1972 | United States, Latin America | Athletes, Victims of racism, Victims of natural disasters, Pittsburgh, Puerto Rico, Latin Americans | Baseball player and humanitarian (1955–1972) | |

| Inocencia Flores | 1977 | Cementerio General de Oruro, Oruro, Bolivia | Unidentified Bolivian murder victim whose grave is the center of local devotion, especially on All Saints' Day.[22] | |||

| Josip Broz Tito | 1980 | Former President of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1953–1980) | |||

| Seraphim Rose | 1982 | Saint Herman of Alaska Monastery, Platina, California, United States | American Hieromonk, theologian, mystic, author; co-founded Saint Herman of Alaska Monastery | |||

| Ferdinand Marcos | 1989 | Rizalian Brotherhood, San Quintin, Abra, Philippines[23] | people of Ilocos Norte | 10th President of the Philippines (1965–1986) | |

| Arsenie Boca | 1989 | Prislop Monastery, Hunedoara, Romania | Romanian Orthodox priest, theologian, mystic, and artist | ||

| Pablo Escobar Gaviria | 1993 | drug trade, Medellín Cartel, drug lords, protection from harm | Colombian drug lord and narcoterrorist who was the founder and sole leader of the Medellín Cartel | ||

| Yevgeny Rodionov | 1996 | Kuznetsky District, Penza Oblast, Russia | Russian soldier killed in First Chechen War | ||

| Diana, Princess of Wales | 1997 | Althorp, Northamptonshire, United Kingdom | mental health, personal problems, protection from tabloid journalism | First wife of King Charles III, mother of Prince William and Prince Harry | |

| Miriam Alejandra "Gilda" Bianchi | 1996 | Gilda Shrine, Entre Ríos, Argentina | healing, Gilda fanatics | Argentine cumbia singer and songwriter | |

| Vangeliya Pandeva Gushterova (known as Baba Vanga) | 1996 | Church of St Petka of the Saddlers, Sofia, Bulgaria | physical healing, personal problems, prophecies of life | Bulgarian clairvoyant and mystic | ||

| Rodrigo Bueno | 2000 | Argentine singer of cuarteto music | ||||

| Nikolay Guryanov | 2002 | Russian Orthodox priest and mystic | ||||

| Tomislav Štrbulović (known as Thaddeus of Vitovnica) | 2003 | Vitovnica Monastery, Serbia | Serbian Orthodox archimandrite, elder, author, and mystic | ||

| Felipe Camiroaga[24][25] | 2011 | Paseo de los sueños, Estación Central, Región Metropolitana, Chile. | Women, housewives | Chilean television personality | |

| Hugo Rafael Chávez Frías (Known as "El Comandante Chávez")[26][27] | 2013 | 23 de Enero, | Chavism | Ex Venezuelan President, Bolivarian Revolution Leader | |

| Nazario Moreno González | 2014 | Holanda and Apatzingán, Mexico | La Familia Michoacana, Knights Templar Cartel, people of Michoacán, protection from harm, protection from Los Zetas | Mexican drug lord | ||

| Marie-Paule Giguère | 2015 | Our Lady of All Nations Church, Quebec, Canada | Community of the Lady of All Nations | Canadian mystic and religious movement founder | ||

| Bhumibol Adulyadej | 2016 | Wat Bowonniwet Vihara, Phra Nakhon district | Thai people | King of Thailand (1946–2016; venerated along with the rest of the living Thai royal family) | |

| Dobri Dobrev | 2018 | Kremikovtsi Monastery, Sofia, Bulgaria | Bulgarian ascetic | ||

| Diego Armando Maradona | 2020 | Maradona Shrine, Naples, Italy | Iglesia Maradoniana | Argentine professional football player and manager | |

| Legendary folk saints | ||||||

| Lin Moniang (Mazu) | most countries in Southeast Asia | The ocean and patroness of seafarers, health, fertility, business | Chinese female deity and protector of Southeast Asians | ||

| Saint Sarah | Church of the Saintes Maries de la Mer, Camargue, France | Romani people | |||

| Escrava Anastacia | Church of Our Lady of the Rosary, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | abused victims | A slave woman of African descent wearing an oppressive facemask. | ||

| Niño Compadrito | Cuzco, Peru | Son of a Spanish viceroy and an Inca princess | ||||

| Master Rákóczi (known as Count Saint Germain) | French spiritual master on Theosophical and post-Theosophical teachings | ||||

| María Lionza | Cerro María Lionza Natural Monument, Yaracuy, Venezuela | nature, love, peace, harmony, indigenous religions in Venezuela | Venezuelan goddess | ||

| Guaicaipuro | Venezuelan chief of both the Teques and Caracas tribes | ||||

| Saint Wilgefortis (known as Librada) | Western Europe and some parts in Latin America | Sigüenza Cathedral, Sigüenza, Spain | relief from tribulations, in particular by women who wished to be liberated ("disencumbered") from abusive husbands, facial hair | Female saint who grew a beard | |

| Saint Baltasar | Concepción, Tucumán | Fernando de la Mora, Paraguay | A crowned black man wearing a red robe or cloak and carrying a scepter or a staff associated with Saint Balthazar, the wise | ||

| Lazarus (known as Lazarus, the poor) | Poor people, lepers, Order of Saint Lazarus | Legendary beggar whose story was told in one of Jesus' parables | |||

| Saint Senara | St Senara's Church, Zennor, Cornwall, England | Zennor | Legendary Breton princess accused of adultery and thrown into the sea in a barrel while pregnant, washed up in Cornwall and founded Zennor | |||

| Saint Amaro | Ermita de San Amaro, Puerto de la Cruz | Disabled People | Catholic Abbot and sailor who claimed to have sailed across the Atlantic Ocean and reached paradise | ||

| Saint Leticia | Church of San Pedro, Ayerbe, Spain | Ayerbe | woman venerated as a virgin martyr and companion of Saint Ursula | ||

| Celestina Abdenago (known as Anima Sola) | relief from tribulations | Woman pictured suffering alone in purgatory for allegedly withholding water to Jesus | |||

| Jesús Juarez Mazo (known as Jesús Malverde) | Culiacan, Sinaloa, Mexico | drug cartels, drug trafficking, outlaws, bandits, robbers, thieves, smugglers, people in poverty | Robin Hood figure of Mexico | ||

| Saint Sicarius of Bethlehem (known as Sicarius of Brantôme) | Abbey church of Saint-Pierre de Brantôme | Invoked for general cures | One of the victims of the Massacre of the Innocents | ||

| Saint Raja | Rajinovac Monastery Spring | Begaljica, Hard workers | A servant who was killed by his master's sons[28][29][30][31][32] | |||

| Deolinda Correa (known as Difunta Correa) | Vallecito, Argentina | cattle herders, ranches, truck driver, gauchos | Argentine mother found dead with a baby | ||

| Aunt Bibija | Parts of the Balkans | Chapel of Aunt Bibija, Belgrade, Serbia | Good health, Children, Romani people | A healer who miraculously cured children | ||

| Holy Child of La Guardia | Monastery of St. Thomas of Avila, La Guardia, Spain | Spanish child allegedly murdered in a blood libel; story used as justification for the public execution of several Jews and conversos; no evidence was ever found and the child's existence is disputed | |||

| Antonio Gil (known as Gauchito Gil) | Sanctuary of Gauchito Gil, Pay Ubre, Mercedes, Corrientes | gauchos, protection from harm, luck, fortune, good health, love, healing, outlaws, bravery, deserters, folk heroes, cowboys, safe passage | Robin Hood figure of Argentina | ||

| Santa Claus | Worldwide belief | Legendary character who is said to bring gifts on Christmas Eve associated with Saint Nicholas of Myra | |||

| Saint Demetra | Byzantine and Ottoman Greece | Gateway in Eleusis, Greece | Agriculture | Christianization of the Greek goddess Demeter[33] | |

| Folk saints recognized by the Catholic Church | ||||||

| Saint Menelphalus of Aix | 430 | Aix Cathedral, Aix-en-Provence, France | Aix-en-Provence | 5th century metropolitan Archbishop of Aix | ||

| St Miliau | 6th century | Guimiliau Parish close, Guimiliau, Brittany, France | Miners, blacksmiths, farm animals, against Rheumatism, Saint-Méen-le-Grand | Breton prince martyred by his evil brother | |

| Saint Nectan (known as Nectan of Hartland) | 510 | Saint Nectan's Glen, Trethevy, Cornwall, England | Fishermen, protection against floods, protection against witchcraft, healing, Hartland, Devon | 5th century Brythonic holy man and hermit, son of King Brychan Brycheiniog | ||

| King Saint Clovis I | 511 | Basilica of Saint-Denis, Saint-Denis, France | France | First King of the Franks, founder of the Merovingian dynasty, raised pagan but converted to Christianity on Christmas Day 496 AD | |

| St. Cannera | 530 AD | St. Canera's Church, Neosho, Missouri | Against drowning, water safety, sailors, against aquaphobia, against nyctophobia | Irish virgin and hermitess | |

| Hildegard of the Vinzgau | 783 | Abbey of Saint-Arnould, Metz, France | Holy Roman Empire | Queen consort of the Franks and second wife of Charlemagne | |

| Charlemagne the Great | 814 | Aachen Cathedral, Aachen, Germany | Holy Roman Empire, Germany, against separatist wars, justice, political leaders | King of the Franks who founded the Carolingian Empire after being crowned Emperor of the Romans by the Pope in 800; Beatified in 1179 | |

| Fulbert of Chartres | 1028 | Cathedral of Our Lady of Chartres, Chartres, France | Teachers, architects and builders, musicians, Diocese of Chartres | 11th century bishop of Chartres, hymnist, teacher, and theologian | |

| Saint David of Munktorp | 1082 | Munktorp Church, Munktorp, Västmanland, Sweden | Mentally ill, the insane, protection from fire, diocese of Västerås, Munktorp | Anglo-Saxon Bendictine monk and missionary to Sweden | |

| Peter of Montboissier (known as Saint Peter the Venerable) | 1156 | Cluny Abbey, Cluny, France | Cluny Abbey, Benedictines, scholars | 12th century French Benedictine Abbot, author, theologian, scholar, and philosopher | |

| Saint Christina the Astonishing (known as Christina Mirabilis) | 1224 | Church of Saint Catherine, Sint-Truiden, Belgium | Millers, people with mental disorders | Flemish woman who suffered a seizure and was presumed dead, only to have come back to life during her funeral and levitate in the air | |

| Gilbert de Moravia (known as Saint Gilbert of Dornoch) | 1245 | Dornoch Cathedral, Dornoch, Scotland | Protection against oppression and injustice, physical and emotional violence, bishops, Caithness, Sutherland, Dornoch Cathedral | 13th century Gaelic bishop of Caithness | ||

| Gundisalvus of Amarante (known as Saint Gundisalvus of Amarante) | 1259 | Saint Gundisalvus Monastery, Amarante, Portugal | Women (especially older women) who want to get married, viola players, architects, pilgrims, people who have suffered attacks | Portuguese Dominican priest remembered for his devotion and humility to whom several miraculous events are attributed; Beatified in 1561 | |

| Werner of Oberwesel | 1287 | Saint Werner's Chapel, Bacharach, Germany | Winemakers | Palatine teen whose unexplained death was blamed on Jews; officially venerated by the Diocese of Trier until his cult was suppressed in 1963 | |

| Anderl Oxner von Rinn (known as Andreas Oxner and the Child of Judenstein) | 1462 | Anderl Chapel, Judenstein, Rinn, Tyrol, Austria | Children, emotional distress, physical ailments, Judenstein | Austrian boy who was known for his devotion to God and mystical visions; allegedly murdered in a blood libel; beatified in 1752 by Pope Benedict XIV | |

| Simon of Trent (known as Simon Unverdorben) | 1475 | Church of St. Simon and St. Jude, Trent, Italy | Children, kidnap victims, torture victims | Italian boy allegedly murdered in a blood libel; beatified in 1588 by Pope Sixtus V; cult suppressed in 1965 by Pope Paul VI | |

| Joanna, Princess of Portugal (known as Princess Saint Joanna) | 1490 | Church and Convent of Jesus, Aveiro, Portugal | Aveiro | Portuguese princess who wanted to be a nun; Beatified in 1693 | |

| Sepé Tiaraju | 1756 | Cathedral of St. Francis of Paola, Pelotas, Brazil | Guarani leader; Cause for beatification opened in April 2017[citation needed] | ||

| Francisca de Paula de Jesus (known as Nhá Chica) | 1895 | Our Lady of Conception Sanctuary, Baependi, Brazil | Brazilian poor, people ridiculed for their faith, devotees of the Immaculate Conception | Afro-Brazilian called "Mother of the Poor" known for her devotion to Our Lady; Beatified in 2013 | |

| José Gregorio Hernández (known as Doctor of the poor) | 1919 | La Candelaria Church, Mérida, Venezuela | medical students, diagnosticians, doctors, medical patients | Venezuelan physician; Beatified in 2021[34] | |

| Antônio da Rocha Marmo (known as Antoninho) | 1930 | Chapel of Our Lady of Health, São José dos Campos, São Paulo, Brazil | Brazilian boy with tuberculosis who dreamed of becoming a Roman Catholic priest; Cause for sainthood opened in 2007 | ||

| Cícero Romão Batista (known as Padre Cícero) | 1934 | Capela do Socorro, Juazeiro do Norte, Ceará, Brazil | Juazeiro do Norte | Brazilian Roman Catholic priest and politician; Cause for sainthood opened in August 2022 | |

| Odette Vidal Cardoso (known as Odetinha) | 1939 | Basilica of the Immaculate Conception, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | Brazilian girl known for her prayer life, acts of charity and purity; Declared Venerable in November 2021 | ||

| Sãozinha de Alenquer (known as the Little Flower of Abrigada) | 1940 | Mausoleum of Sãozinha, Alenquer, Portugal | Young Portuguese girl remembered for her dedication to the Catholic faith and her purity; Cause for sainthood opened in 1994 | ||

| Phanxicô Xaviê Trương Bửu Diệp | 1946 | Nhà nguyện Trương Bửu Diệp, Giá Rai, Bạc Liêu, Vietnam | Vietnamese priest and martyr; Cause for sainthood opened in January 2012 | |||

| Francisco Rodrigues da Cruz (known as Padre Cruz) | 1948 | Mausoleum of Padre Cruz, Benfica Cemetery, Lisbon, Portugal | Priests, sick, prisoners, poor, devotees of the Immaculate Heart of Mary | Portuguese priest revered for his apostolic fervor and charity; Cause for sainthood opened in March 1951 | |

| Melchora Saravia Tasayco (known as La Melchorita) | 1951 | Santuario de la Beata Melchorita, Chincha, Peru | Peruvian Franciscan tertiary and mystic; Cause for sainthood opened in April 1978 | ||

| Bernard Francis Casey (known as Solanus Casey) | 1957 | St. Bonaventure Monastery, Detroit, Michigan, United States | Broadcasters, pro-life activists, the poor and marginalized, healing, vocations, Detroit | American priest, friar and religious leader; Beatified in 2017 | |

| Charlene Richard (known as the Little Cajun Saint) | 1959 | St. Edward Church, Richard, Louisiana, United States | Cajun people, good health, converts to Catholicism | Cajun girl who died of leukemia; Cause for sainthood opened in January 2020 | ||

| Nelson Santana (known as Nelsinho) | 1964 | Senhor Bom Jesus Church, Ibitinga, São Paulo, Brazil | Brazilian boy who died of cancer and found solace in faith; Declared Venerable in May 2019 | |||

| Fulton Sheen | 1979 | St. Mary's Cathedral, Peoria, Illinois, United States | Broadcasters, pro-life activists, Catholic educators, Catholic converts, those who suffer from addictions | American bishop, author, teacher, theologian, radio host, and televangelist; Beatification scheduled for 2019 but delayed | |

| Maria Aparecida Berushko (known as Tita) | 1986 | Ukrainian Orthodox Parish of Saint Nicholas, Joaquim Távora, Paraná, Brazil | Teachers, students, schooling | Brazilian teacher who donated her life to save her students from a fire; Cause for sainthood opened in October 2005 by Orthodox Church of Ukraine | |

| Maria Rita de Sousa Brito Lopes Pontes (Known as Sister Dulce of the poor) | 1992 | Roma, Salvador, Bahia, Brazil | Poor, homeless, beggars, sick, prisoners, working class, Baianos. | Brazilian Catholic noun Known for defending marginalized people; Canonized on 13 October 2019 by the Catholic Church. First Brazilian female saint. | |

| Popular saints identified with folkloric beings | ||||||

| Santa Muerte | Central America | Shrine of Most Holy Death, Mexico City, Mexico | love, prosperity, good health, fortune, healing, safe passage, protection against witchcraft, protection against assaults, protection against gun violence, protection against violent death, safe delivery to the afterlife | Mexican female deity and personification of death | |

| San La Muerte | restore love, good fortune, gambling, protection against witchcraft, protection against imprisonment, inmates, prisoners, luck, good health, vengeance | Skeletal folk saint; male version of Santa Muerte | |||

| San Pascualito (known as San Pascualito Muerte) | Capilla de San Pascualito, Olintepeque, Guatemala | curing diseases, death, healings, cures, vengeance, love, graveyards | Folk saints associated with Saint Paschal Baylon | ||

| El Tío (known as Lord of the Underworld) | Cerro Rico, Potosí Bolivia | Miners | Figure associated with the devil who receives gifts in exchange for protection | ||

| Maximón | Santiago Atitlán, Guetamala | health, crops, marriage, business, revenge, death | Mayan deity | ||

| Animals venerated as folk saints | ||||||

| Saint Guinefort | 13th century | Dogs, dog owners, children, infants | 13th-century French Greyhound; devotion suppressed by the Catholic Church but persisted until 1930 | ||

See also

[edit]- Apotheosis

- Folk religion

- Chinese folk religion

- Orisha

- Phallic saint

- Secular saint

- Military saint

- Category:Supernatural beings identified with Christian saints

References

[edit]- ^ Michael Frishkopf. (2001). "Changing Modalities in the Globalization of Islamic Saint Veneration and Mysticism: Sidi Ibrahim al-Dasuqi, Shaykh Muhammad 'Uthman al-Burhani, and the Sufi Orders," Religious Studies and Theology 20(1):1

- ^ Octavio Ignacio Romano V. (1965). "Charismatic Medicine, Folk-Healing, and Folk Sainthood," American Anthropologist 67(5):1151–1173. p. 1157.

- ^ Graziano, Frank (2006). Cultures of Devotion: Folk Saints of Spanish America. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 9–10.

- ^ Kathleen Ann Myers. 2003. Neither Saints Nor Sinners: Writing the Lives of Women in Spanish America. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 23.

- ^ Griffith, James S. (2003). Folk Saints of the Borderlands: Victims, Bandits & Healers. Tucson: Rio Nuevo Publishers. p. 152.

- ^ William A Christian Jr. (1973) "Holy People in Peasant Europe," Comparative Studies in Society and History 15(1):106-114. p. 106

- ^ Christian, p. 107

- ^ Lois Parkinson Zamora. 2006. The Inordinate Eye: New World Baroque and Latin American Fiction. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- ^ "From Village Boy to Soldier, Martyr and, Many Say, Saint" The New York Times, November 21, 2003.

- ^ Watson, Julie (2001-12-16). "Residents along U.S.-Mexican border find strength in local folk saints". www.latinamericanstudies.org. The Miami Herald. Retrieved 2025-03-24.

- ^ Griffith p. 19.

- ^ sheldon, Natasha (2017-06-22). "The Girl in the Iron Mask: The Legend of the Slave Girl, St. Escrava Anastacia". History Collection. Retrieved 2023-10-16.

- ^ Christian pp. 108–109.

- ^ Graziano, p. 29

- ^ Pasciuto, Greg (2023-05-08). "La Santa Muerte: Mexico's Macabre Religion at Odds with the Church". TheCollector. Retrieved 2024-02-12.

- ^ A., F. S. (1875). "The Editor Box". The Penny Post. 25. J.H. Parker: 81. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ irishfolkartproject (2017-09-24). "Some Galway Folk Art. The story of Stoney Brennan Loughrea". Irish Folk Art Project. Retrieved 2024-03-02.

- ^ Brogan, Fergus (2018-03-13). "13. STONEY BRENNAN". Galway County Heritage Office. Retrieved 2024-03-02.

- ^ The curious story of Maria Adelaide

- ^ AsiaNews.it. "Controversy in Moscow: Stalin icon revered". www.asianews.it. Retrieved 2022-05-13.

- ^ Sources:

- "Paralyzed high jumper overcomes injury to walk down the aisle at his wedding". Los Angeles Times. July 23, 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- Graham, Pat (July 22, 2017). "Injured Olympian Walks at Wedding Despite Odds of Never Walking Again". NBC. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- Chavez, Chris (July 22, 2017). "Paralyzed Olympian Jamie Nieto Walks at Wedding". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- Graham, Pat (July 5, 2017). "Injured US Olympian defies doctors to walk for his wedding". New Haven Register. Associated Press. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- Withiam, Hannah (August 17, 2017). "The complicated battle over Roberto Clemente's sainthood". New York Post. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- "Close to Holiness". Washington Post. El Diario. August 18, 2017. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ^ Ferrufino, Estela Llanque (13 December 2022). "LA SANTA "INOCENCIA FLORES"". ElSajama.com Prensa | Noticias de Oruro, Deportes, Cultura, Sociedad y más (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 February 2025.

- ^ "Cult of Marcos rises among his former subjects". Independent. 2011-10-23. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- ^ "8 años de la tragedia de Juan Fernández: el culto popular a Felipe Camiroaga". Publimetro Chile (in Spanish). 2019-09-02. Retrieved 2024-11-05.

- ^ "Felipe Camiroaga ya es santo de la devoción de muchos chilenos | Crónica". La Cuarta (in Spanish). 2014-09-02. Retrieved 2024-11-05.

- ^ Amaya, Víctor (2023-03-04). "Capilla "santo Hugo Chavez del 23" ha ido quedando sin devotos". TalCual (in Spanish). Retrieved 2025-02-25.

- ^ "Así adoran a Hugo Chávez en Venezuela". El Colombiano (in European Spanish). Retrieved 2025-02-25.

- ^ "IZVOR SVETE VODE KOJA ISCELJUJE Neverovatna priča krije se iza imena ovog manastira, nadaleko čuven po ovoj ikoni! | Lepote Srbije".

- ^ "Rajin novac sagradi manastir - Život - Dnevni list Danas". 27 July 2007.

- ^ "Manastir Rajinovac - Travel.RS". 12 April 2011.

- ^ "Istorijat manastira Rajinovac".

- ^ "NAROD VERUJE DA IZVOR NADOMAK BEOGRADA IMA SVETU VODU KOJA ISCELJUJE: Neverovatna priča krije se iza imena manastira kod Grocke". 17 June 2023.

- ^ Keller, Mara Lynn (1988). "The Eleusinian Mysteries of Demeter and Persephone: Fertility, Sexuality, and Rebirth". Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion. 4 (1): 27–54. ISSN 8755-4178. JSTOR 25002068.

- ^ Venezuela celebrates as 'doctor of the poor' beatified

This article incorporates material from the Citizendium article "Folk saint", which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License but not under the GFDL.

Sources

[edit]- Graziano, Frank (2007). Cultures of Devotion: Folk Saints of Spanish America. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517130-3.

- Griffith, James S. (2003). Folk Saints of the Borderlands: Victims, Bandits & Healers. Tucson: Rio Nuevo Publishers. ISBN 1-887896-51-1.

- Macklin, B.J.; N.R. Crumrine (1973). "Three North Mexican Folk Saint Movements". Comparative Studies in Society and History. pp. 89–105.

External links

[edit] Media related to Folk saints at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Folk saints at Wikimedia Commons

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch