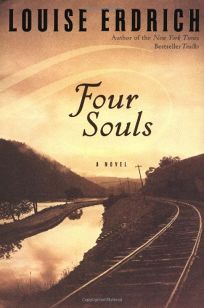

Four Souls (novel)

| |

| Author | Louise Erdrich |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Series | Love Medicine |

| Genre | Fiction |

| Published | 2004 (HarperCollins) |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | |

| ISBN | 9780066209753 |

Four Souls (2004) is an entry in the Love Medicine series by Chippewa (Ojibwe) author Louise Erdrich. It was written after The Master Butcher’s Singing Club (2003) and before The Painted Drum (2005); however, the events of Four Souls take place after Tracks (1988).[1] Four Souls follows Fleur Pillager, an Ojibwe woman, in her quest for revenge against the white man who stole her ancestral land. Fleur appears in many books in the series, and this novel takes place directly after her departure from the Little No Horse reservation at the end of Tracks. The novel is narrated by three characters, Nanapush, Polly Elizabeth, and Margaret, with Nanapush narrating all of the odd numbered chapters and Polly Elizabeth taking all but the last two even numbered chapters.

Background

[edit]The first edition of Four Souls was first published in 2004.[1] Erdrich's original intentions had been to place Fleur's story in an extended revised version of Tracks, but she eventually decided to write Four Souls instead, giving an entire novel to Fleur's journey and leaving the plot of Tracks as is.[1] Woven throughout Four Souls, and many of the novels concerning Erdrich's fictional reservation and its inhabitants, is the thread of an intricate narrative that affects events and characters across the series. As in history, the Ojibwe people within her novels face the appropriation of land by the government, removal, and the allotment process meant to encourage farming and eventual assimilation which were a result of western expansion.[2] During this time, there were also outbreaks of the diseases brought with settlers, most notably the diseases that can be presumed to be smallpox and possibly tuberculosis.[2]

Genre

[edit]Like many of her other novels, especially the other novels within the Love Medicine series, Erdrich uses a blend of “intertextuality, multiple perspectives, and temporal dislocation” to create the narrative of Four Souls.[1] Many consider this book to be written in a post-modernist style and suggest Erdrich's works may have been influenced by modernist William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County stories due to the highly interconnected relationships and characters within her novels.[2] Within Four Souls, Erdrich uses her Ojibwe ancestry to give a strong sense of realism to the characters and their lives. An obvious instance of such would be the inclusion of Nanapush, who is based on the Ojibwe narrative tradition of an Anishinaabe trickster.[3] Erdrich also uses various Ojibwe terms and phrases throughout the perspective of Ojibwe narrators, though that has led to some criticism from other Ojibwe writers such as David Treuer.[2]

Setting

[edit]The events of the novel occur around the early 1900s on the fictional Ojibwe reservation of Little No Horse and the Minneapolis-Saint Paul area.[1] The exact location of the reservation is unclear; however, it is presumed to be in North Dakota.[1] Fleur leaves the reservation in North Dakota and follows train tracks to Minnesota to take revenge on the lumber baron, John James Mauser, who stole her land and razed the forest for lumber.[4] There she lives in his newly built mansion on the outskirts of St. Paul while planning her revenge.[5]

Characters

[edit]- Fleur Pillager: The main protagonist and an Ojibwe woman. She takes on the name of her late mother, Four Souls, while in pursuit of revenge on the man that stole her land.

- Nanapush: The adoptive father of Fleur, a mischievous Ojibwe elder and the primary narrator. Nanapush is based on the figure of the traditional Anishinaabe trickster of Nanabozho.

- Polly Elizabeth: Sister of Placide Gheen, John James Mauser's sister-in-law.

- Placide Gheen: Formerly married to John James Mauser.

- John James Mauser: Owner of logging company, person who stole Fleur's land and stripped it of all the trees; husband of Fleur; former husband of Placide.

- Fantan: A mute male server in Mauser household.

- Mrs. (Nettie) Testor: Servant in the mansion of John James Mauser.

- Margaret Kashpaw: Partner of Nanapush, known as Rushes Bear.

- The boy (John James Mauser II): Son of Fleur and John James Mauser.[5]

Family Tree

[edit]

Legend

[edit]

Summary

[edit]The novel opens with Fleur walking towards the city where Mauser lives. Mauser has stripped Fleur's land of the trees there, and she leaves on foot to get her revenge. Before entering the city, Fleur buries the bones of her ancestors and takes on her mother's secret name, “Four Souls.”[5] Once Fleur arrives in the city, she makes her way to the house Mauser has recently built, presumably with the trees from her land. She arrives just in time to be given a job as a laundress by Polly Elizabeth. Here we learn that Mauser has been suffering from debilitating convulsions and sickness that has left him unable to even manage his own house. This soon changes as Fleur begins to treat Mauser, not out of kindness, but because she wants him to suffer at her hands, not at the mercy of a disease. Once Mauser is healthy, she sneaks into his room to kill him, but takes pity on the suppliant Mauser, and the two enter into a sexual relationship.[5]

Polly Elizabeth is unhappy with the most recent turn of events. Mauser has divorced Placide and made Fleur the new lady of the house, removing Polly from her seat of power and influence. Polly returns to the house often to gossip about the couple with Mrs. Testor, and she soon learns that Fleur is pregnant but dealing with complications. Polly offers help and quickly makes herself necessary to Fleur in her pregnancy. Polly feeds Fleur a steady stream of whiskey to calm her nerves and keep the baby from being born prematurely.[5] When the child, a boy, is born, he is restless and can only be calmed by a drop of whiskey, much like his mother who is also now dependent on the “golden fire” to function. Polly expresses concern for Fleur's alcoholism but is preoccupied with caring for the child.[5]

On the Little No Horse reservation, Margaret has become obsessed with covering the dirt floor of her and Nanpush's home with linoleum. She goes to great lengths to acquire the material, selling a portion of her son's allotment. Nanapush views this as an act of betrayal to their family and their people, and it causes a great deal of strife in their home.[5]

In the Mauser household, Polly continues to raise and spoil the boy, but it becomes evident that he has been born with a mental “condition.” Since Mauser is on the board of the hospital, and the doctors fear upsetting him, the boy goes undiagnosed. Mauser feels shame at his son's condition and blames it on his own past wrongdoings.[5]

Meanwhile, on the reservation, Margaret works on a medicine dress that appeared to her in a vision. She makes a teasing joke at Nanapush's expense, causing him to leave in outrage and steal wine from the church cellar. When he finally returns home, Margaret is upset but unaware of the wine's origin. Nanapush asks Margaret to put on the medicine dress, and though he is in awe of her beauty, criticizes her dancing. He dons the dress himself to demonstrate proper dancing technique, but Margaret is gone.[5] Nanapush returns to the church cellar, but the nuns catch him and lock him in. The next morning after waking in his cell, Nanapush makes his way to a council meeting over which he must preside as committee chairman. He arrives, still in the medicine dress, and delivers a moving and successful speech. After these events, Nanapush accidentally burns a hole into Margaret's linoleum floor. His attempt to cover it up is quickly discovered; however, it leads to a positive end for the couple's disputes. Margaret then recounts the vision given to her of her medicine dress and describes the process of making it.[5]

Not long after Margaret finishes the dress, Fleur returns to the reservation with her son. She spends time around the reservation, but eventually joins the “game of nothing,” a seemingly never-ending poker game run by the head of the bar. Fleur wins the game, and with it her land, as it had been bought by the bar owner after Mauser failed to pay the property taxes. The morning after, Margaret realizes Fleur has not given her son a name. Fleur makes excuses, but Margaret refuses to accept them. Margaret then begins the long process of healing Fleur's broken spirit and finding her a new name, as “Four Souls” is no longer the proper name for her. After these events, Fleur returns home to live in the woods on her land.[5]

Analysis

[edit]Dr. P. Jane Hafen (Taos Pueblo) analyzes Erdrich's works through the lens of tribalography, a term coined by Choctaw author LeAnne Howe, to show how Native stories, that is narratives written by Native authors concerning Native characters, have a “propensity for bringing things together."[6] Howe calls this propensity a “cultural bias” and a necessary aspect of Native storytelling.[7] Hafen argues that this is the best way to analyze Erdrich's works while most other western lenses subsume the author and colonize the narrative.[6] By focusing her storytelling through Native narrators, Erdrich creates a “communal Indian voice [that] relates the story of the Plains Ojibwa people.” To Connie A. Jacobs, Erdrich is recounting Native history in the most Indigenous way possible where “stories stand as metaphors… for the major episodes of tribal life.”[8]

Reception

[edit]Michiko Kakutani, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism, wrote an article in The New York Times where she describes the overall storyline of Four Souls as “predictable and trite.”[9] In her review for The New York Times, Karen Fowler writes that “the progression of events feels natural and unforced, full of satisfying yet unexpected twists.”[10] In a review for Publishers Weekly, Andrew Wylie notes Four Souls as a work of “unusual commercial interest.” Wylie concludes his review by considering how the tale seems like an “insiders experience,” which leads to his point that “Erdrich may not ensnare many new readers, but she will already satisfy her already significant audience.”[11]

Publication

[edit]In the 2003 issue of The New Yorker, altered sections of the novel's ninth and eleventh chapters appear under the title “Love Snares.”[12] Subsequently, in 2004, HarperCollins published the novel and Louise Erdrich copyrighted Four Souls to her name.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Beidler, Peter G. (1999). A reader's guide to the novels of Louise Erdrich. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0826260055. OCLC 56424901.

- ^ a b c d Stirrup, David (2011). Louise Erdrich : Louise Erdrich. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- ^ Mary Magoulick (2018). "Trickster Lives in Erdrich: Continuity, Innovation, and Eloquence of a Troubling, Beloved Character". Journal of Folklore Research. 55 (3): 87–126. doi:10.2979/jfolkrese.55.3.04. JSTOR 10.2979/jfolkrese.55.3.04. S2CID 150211719.

- ^ Kurup, Seema (2016). Understanding Louise Erdrich. University of South Carolina Press. p. 45.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Erdrich, Louise. (2004). Four Souls. New York: Harper Collins Publishers.

- ^ a b Hafen, P. Jane (2013). "On Louise Erdrich". In Hafen, Jane P. (ed.). Critical Insights: Louise Erdrich. Massachusetts: Salem Press. p. 14.

- ^ Howe, LeAnne (2013). Choctalking on Other Realities. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-879960-90-9.

- ^ Jacobs, Connie A. (2001). The Novels of Louise Erdrich: Stories of Her People. New York: Peter Lang Publishing. p. 85.

- ^ Kakutani, Michiko (2004-07-06). "BOOKS OF THE TIMES; A Mystic With Revenge on Her Mind". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-03-26.

- ^ Fowler, Karen (July 4, 2004). "Off the Reservation". The New York Times. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ Wylie, Andrew (July 2, 2004). "FOUR SOULS (Book)". Publishers Weekly. 19 (251): 33. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- ^ Erdrich, Louise (October 27, 2003). "Love Snare". The New Yorker. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

For further reading

[edit]- Genzale, Ann M. “Medicine Dresses and (Trans)Vestments: Gender Performance and Spiritual Authority in Louise Erdrich’s The Last Report on the Miracles at Little No Horse and Four Souls.” Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction 58, no. 1 (2017): 28–40.

- Sawhey, Brajesh. Studies in the Literary Achievement of Louise Erdrich. New York: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2009.

- Summer, Harrison. “The Politics of Metafiction in Louise Erdrich’s Four Souls” in Studies in American Indian Literatures 23, no. 1 (2011).

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch