Soc Rodrigo

Soc Rodrigo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Senator of the Philippines | |

| In office December 30, 1955 – December 30, 1967 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Francisco Aldana Rodrigo January 29, 1914 Bulakan, Bulacan, Insular Government of the Philippine Islands, U.S. |

| Died | January 4, 1998 (aged 83) Quezon City, Philippines |

| Political party | Lakas ng Bayan (1978–1983) |

| Other political affiliations | Liberal (1961–1978) Nacionalista (1955-1961) |

| Spouse | Remedios Enriquez (m. 1937) |

| Children | 6 |

| Alma mater | Ateneo de Manila University (BA) University of Santo Tomas (BS) University of the Philippines Diliman (LL.B.) |

| Occupation | Politician |

| Profession | Lawyer |

Francisco "Soc" Aldana Rodrigo (January 29, 1914 – January 4, 1998) was a Filipino playwright, lawyer, broadcaster, and a Senator of the Philippines from 1955 to 1967.

In honor of in the struggle against the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos, his name was inscribed on the Wall of Remembrance at the Bantayog ng mga Bayani in 1998 - the year in which he died.[1][2] A national cultural award named in his honor, the Gawad Soc Rodrigo is given by the Philippines' Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino (KWF) and National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA).

Personal life

[edit]Rodrigo was born on 29 January 1914 in Bulacan, Bulacan, to food vendor Marcela Aldana and horse-carriage driver Melecio Rodrigo. He was a relative to the Filipino heroes Marcelo del Pilar and Gregorio del Pilar.[3]

In 1937, Rodrigo married his childhood sweetheart Remedios Enriquez. Prior to this, he took Law at the University of the Philippines, which he finished in 1938.[4]

Education

[edit]Rodrigo received his elementary education from the Bulacan Elementary School, and moved on to secondary school at the University of the Philippines High School. He earned his Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science in Education degrees from Ateneo de Manila and University of Santo Tomas, graduating magna cum laude and valedictorian, respectively. He was captain of the debate team at university. He then earned His Bachelor of Laws degree from the University of the Philippines Diliman.

Career

[edit]Literary works

[edit]Rodrigo was a playwright in English and Tagalog, with works described as those that distilled within the Filipino soul. His most celebrated play was Sa Pula, Sa Puti while his most popular Kuro – Kuro sa likod ng mga Balita had also won legions of admirers throughout the country. Some other famous works include Tagalog translations of works of Martyr of Golgotha and Cyrano de Bergerac.[4] Rodrigo was also known for his tanaga.

World War II

[edit]During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines in World War II, Rodrigo distributed anti-Japanese propaganda materials together with Raul Manglapus and Manuel Fruto. In his book Mga Bakas ng Kahapon (Traces of the Past), Rodrigo reflected on the fate he and his family of four may have suffered had he been implicated by Manglapus and Fruto during their capture. In 1945, he moved his family to the underground basement of the Philippine General Hospital in Manila, where they survived the building's destruction.

Postwar Law and broadcasting career

[edit]After the war, Rodrigo resumed his law practice by joining the law firm of Francisco Delgado and Lorenzo Tañada. Then, he opened the Rodrigo Law Office in 1946. Rodrigo authored Philippine Modern Legal Forms and Handbook on the Rules of Court.

In 1951, Rodrigo became the president of the Ateneo Parent-Teacher Association, then became the president of the Ateneo Alumni Association in 1953. In 1953, Rodrigo and Bob Stewart ran an unprecedented 48-hour coverage of the entire proceedings of the 1953 Philippine presidential elections.[4] Rodrigo was awarded by President Ramon Magsaysay a Legion of Honor due to this marathon broadcast.

Philippine Senate service

[edit]In 1955, Rodrigo won a seat in the Philippine Senate under the Nacionalista Party of President Magsaysay. One of Rodrigo's speeches, Catholics in Politics, delivered on 7 September 1957, is included in the Anvil Publishing book 20 Speeches That Moved a Nation.[5]

Awarded as one of the Ten Outstanding Senators of his time, he was a much-invited guest of foreign governments such as the United States, Britain and West Germany, among others. Rodrigo was also awarded a U.S. Government grant under the terms of Public Law 402 (Smith - Mundt) for observation and travel under the auspices of the Governmental Affairs Institute (Nov. 20, 1959 - Jan. 20, 1960).[6]

For the 1959 midterm elections, Rodrigo ran an unsuccessful campaign for the “Grand Alliance” counting as candidates Emmanuel Pelaez, Raul Manglapus and Jorge Vargas, among others. Then in 1961, Rodrigo got the third-most votes to win a second senatorial term as a Liberal Party candidate with Diosdado Macapagal.[7] He sought a third term in 1967 but lost. From 1970 to 1972, Rodrigo hosted the ABS-CBN program Mga Kuro-kuro ni Soc Rodrigo.

Martial Law activism

[edit]For his dissent against President Ferdinand Marcos, Rodrigo, along with Ninoy Aquino and many others, was incarcerated during upon the declaration of Martial Law in 1972. During this time in jail, Rodrigo kept the faith of fellow detainees alive as he led nightly prayers of the rosary. Aquino would treasure the crucifixes that Rodrigo gave him during this time.[2] Rodrigo was released after three months but was detained two more times: in 1978, for writing Tagalog poems attacking the Marcos dictatorship, and in 1982, for his anti-Marcos poems in the newspapers, WE Forum and Philippine Star.

In August 21, 1983, Rodrigo was one of the first people allowed to look at the remains of the assassinated Ninoy Aquino. Rodrigo felt distraught over this incident since he was one of those who advised Aquino to return to the Philippines from exile in the United States.[8]

End of the Marcos dictatorship and service in the 1986 Constitutional Commission

[edit]After the People Power Revolution that sent Marcos to exile, Rodrigo was chosen by President Cory Aquino to be a Commissioner of the 1986 Constitutional Commission. Many of Rodrigo's children were against his being a member, preferring instead to see him in the Senate one more time. Instead, he joined the commission as he turned his back on politics forever. The new Constitution was ratified by the people in February 1987.[9]

Retirement and death

[edit]After his service in the Constitutional Commission, Rodrigo largely retired from public life, preferring to spend time with his family. Until just before his death, though, he wrote columns for the newspapers Malaya (1980–1989) and The Philippine Star (1992–1997).[10]

On January 4, 1998, Rodrigo died at the age of 83 due to complications from cancer.

Legacy

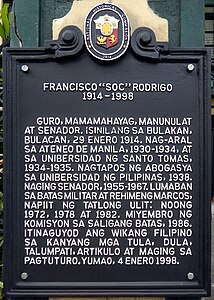

[edit]- NHCP historical marker dedicated to Soc Rodrigo located at the Rodrigo ancestral house in Bulakan, Bulacan.

- Detail of the Wall of Remembrance at the Bantayog ng mga Bayani, showing names from the 1998 batch of Bantayog Honorees, including that of Soc Rodrigo.

In November 1998, a few months after his death, Soc Rodrigo's name was inscribed in the Wall of Remembrance at the Bantayog ng mga Bayani in Quezon City, to honor his role in the struggle against Ferdinand Marcos.[2]

The Gawad Soc Rodrigo is an award named after him given by the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino (KWF) and the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA).

References

[edit]- ^ "Heroes and Martyrs: RODRIGO, Francisco A." Bantayog ng mga Bayani. 2016-07-13. Retrieved 2018-07-13.

- ^ a b c "Remembering a poet, writer, freedom fighter - INQUIRER.net, Philippine News for Filipinos". Newsinfo.inquirer.net. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ^ "Baljolandia - Soc Rodrigo: "Ipinanganak ako.."". Pinoyhistorian.multiply.com. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ^ a b c http://i282.photobucket.com/albums/kk270/kofranks/BluebloodSoc1.jpg [bare URL image file]

- ^ readnow (2007-05-05). "Catholics in Politics by Francisco "Soc" Rodrigo « readnow". Readnow.i.ph. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ^ "Senators Profile - Francisco Soc Rodrigo". Senate.gov.ph. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ^ "Third force often ends up third - INQUIRER.net, Philippine News for Filipinos". opinion.inquirer.net. Archived from the original on 2007-01-16.

- ^ http://i282.photobucket.com/albums/kk270/kofranks/BluebloodSoc2.jpg [bare URL image file]

- ^ http://i282.photobucket.com/albums/kk270/kofranks/BluebloodSoc3.jpg [bare URL image file]

- ^ "Niet compatibele browser". Facebook. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch