Freedom of Speech (painting)

| Freedom of Speech | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Norman Rockwell |

| Year | 1943 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas[1] |

| Dimensions | 116.2 cm × 90 cm (45.75 in × 35.5 in)[1] |

| Location | Norman Rockwell Museum[1], Stockbridge, Massachusetts, United States |

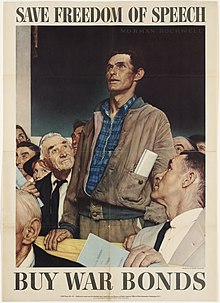

Freedom of Speech is the first of the Four Freedoms paintings by Norman Rockwell, inspired by United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt's 1941 State of the Union address, known as Four Freedoms. The painting was published in the February 20, 1943, issue of The Saturday Evening Post with a matching essay by Booth Tarkington.[2] Rockwell felt that this and Freedom of Worship were the most successful of the set.[3]

Background

[edit]Freedom of Speech was the first of a series of four oil paintings, entitled Four Freedoms, by Norman Rockwell. The works were inspired by United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt in a State of the Union Address, known as Four Freedoms, delivered to the 77th United States Congress on January 6, 1941.[4] Of the Four Freedoms, the only two described in the United States Constitution were freedom of speech and freedom of worship.[5] The Four Freedoms' theme was eventually incorporated into the Atlantic Charter,[6][7] as well as the charter of the United Nations.[4] The series of paintings ran in The Saturday Evening Post, accompanied by essays from noted writers, on four consecutive weeks: Freedom of Speech (February 20), Freedom of Worship (February 27), Freedom from Want (March 6) and Freedom from Fear (March 13). Eventually, the series became widely distributed in poster form and became instrumental in the U. S. Government War Bond Drive. People who purchased war bonds during the 1943–1944 Four Freedoms War Bond Show received a full-color set of reproductions of the Four Freedoms, as well as commemorative covers with Freedom of Speech to store the purchased bonds and war savings postage stamps.[8]

Description

[edit]"The first is freedom of speech and expression—everywhere in the world."

Freedom of Speech depicts a scene of a 1942 Arlington town meeting in which Jim Edgerton, the lone dissenter to the town selectmen's announced plans to build a new school, as the old one had burned down,[9] was accorded the floor as a matter of protocol.[10] Edgerton supported the rebuilding process but was concerned about the tax burden of the proposal, as his family farm had been ravaged by disease.[11] A memory of this scene struck Rockwell as an excellent fit for illustrating "freedom of speech", and inspired him to use his Vermont neighbors as models for the entire Four Freedoms series.[12]

The blue-collar speaker wears a plaid shirt and suede jacket, with dirty hands and a darker complexion than others in attendance.[13] The other attendees are wearing white shirts, ties and jackets.[14] One of the men in the painting is holding a document that reveals a subject of the meeting as "a discussion of the town's annual report".[5] Edgerton's youth and workmanlike hands are fashioned with a worn and stained jacket, while the other attendees appear to be older and more neatly and formally dressed. According to Bruce Cole of The Wall Street Journal, Edgerton is shown "standing tall, his mouth open, his shining eyes transfixed, he speaks his mind, untrammeled and unafraid", and his face resembles Abraham Lincoln.[5] According to Robert Scholes, the work shows audience members in rapt attention with admiration of the speaker, who resembles a Gary Cooper or Jimmy Stewart character in a Frank Capra film.[15] According to John Updike, the work is painted without any painterly brushwork.[16]

Production

[edit]

The model for the shy, brave young workman was Carl Hess, a Rockwell neighbor from Arlington, Vermont. [17] Hess was suggested as a model by Rockwell's assistant, Gene Pelham. Hess, the son of a German immigrant, was a married man who had a gas station in town. His children went to school with the Rockwell children.[9][14] According to Pelham, Hess "had a noble head".[18] The other models were: Carl Hess's father Henry (left ear only), Jim Martin (lower right corner; he would also appear in the other Four Freedoms paintings[17]), Harry Brown (right—top of head and eye only), Robert Benedict, Sr. and Rose Hoyt to the left. Rockwell's own eye is also visible along the left edge.[9] Pelham was the owner of the suede jacket worn by the model.[14] Hess posed for Rockwell eight different times for this work and all other models posed for Rockwell individually.[14]

Rockwell's final product was the result of four restarts and consumed two months.[9][13] Twice he almost completed the work only to feel it was lacking.[19] At one point, Rockwell had to admit to the Post's art director, Jim Yates, that he had to start Freedom of Speech from scratch after an early attempt because he had overworked it.[20] Each version depicted the blue-collar man in casual attire standing up at a town meeting, but each was from a different angle.[13] An early draft had Hess surrounded by others sitting squarely around him. Hess felt the depiction had a more natural look, but Rockwell objected: "It was too diverse, it went every which way and didn't settle anywhere or say anything."[9] In the final version, Rockwell decided on an upward view from the bench level, and focused on the speaker as the subject rather than the assembly.[19]

Essay

[edit]

For the accompanying essay, Post editor Ben Hibbs chose novelist and dramatist Booth Tarkington, who was a Pulitzer Prize winner.[2] Tarkington's accompanying essay published in the February 20, 1943 issue of The Saturday Evening Post was really a fable or parable in which a youthful Adolf Hitler and a youthful Benito Mussolini meet in the Alps in 1912. During the fictional meeting both men describe plans to secure dictatorships in their respective countries via the suppression of freedom of speech.[21]

Critical review

[edit]This image was praised for its focus, and the empty bench seat in front of the speaker is perceived as inviting to the viewer. The solid dark background of the blackboard helps the subject to stand out but almost obscures Rockwell's signature.[22] According to Deborah Solomon, the work "imbues the speaker with looming tallness and requires his neighbors to literally look up to him."[13] The speaker represents a blue-collar, unattached, and sexually available, likely ethnic, threat to social customs who nonetheless is accorded the full respect from the audience.[14] Some question the authenticity of white-collar residents being so attentive to the comments of their blue-collar brethren.[14] Solomon noted the lack of female figures in the picture,[14] though alternate versions of the painting show that the red-haired individual on the left is female.[23]

Laura Claridge said, "The American ideal that the painting is meant to encapsulate shines forth brilliantly for those who have canonized this work as among Rockwell's great pictures. For those who find the piece less successful, however, Rockwell's desire to give concrete form to an ideal produces a strained result."[24]

Bruce Cole describes Freedom of Speech as Rockwell's "greatest painting", "forging traditional American illustration into a powerful and enduring work of art." He notes that Rockwell uses "a classic pyramidal composition" to emphasize the central figure, a standing speaker whose appearance is juxtaposed with the rest of the audience that, by participating in democracy, defends it. Cole describes Rockwell's figure as "the very embodiment of free speech, a living manifestation of that abstract right—an image that transforms principle, paint and, yes, creed, into an indelible image and a brilliant and beloved American icon still capable of inspiring millions world-wide".[5] He notes that the use of a New England town-hall meeting incorporates the "long tradition of democratic public debate" into the work, while the blackboard and pew represent church and school, which, Cole says, are "two pillars of American life."[5]

The Post editor Ben Hibbs said of Speech and Worship: "To me they are great human documents in the form of paint and canvas. A great picture, I think is one which moves and inspires millions of people. The Four Freedoms did—do so."[25] Westbrook notes that Rockwell presents "individual dissent" that acts to "protect private conscience from the state."[21] Another writer describes the theme of the work as "civility".[26]

Legacy

[edit]In the 2020s, Rockwell's painting became the subject of an Internet meme, in which people use the figure depicted in the painting as an allegory for boldly stating opinions widely considered to be unpopular or controversial.[27][28]

See also

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c ""Freedom of Speech," 1943". Norman Rockwell Museum. November 2, 2016. Retrieved April 7, 2024.

- ^ a b Murray and McCabe, p. 61.

- ^ Hennessey and Knutson, p. 102.

- ^ a b "100 Documents That Shaped America:President Franklin Roosevelt's Annual Message (Four Freedoms) to Congress (1941)". U.S. News & World Report. U.S. News & World Report, L.P. Archived from the original on April 12, 2008. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Cole, Bruce (October 10, 2009). "Free Speech Personified: Norman Rockwell's inspiring and enduring painting". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- ^ Boyd, Kirk (2012). 2048: Humanity's Agreement to Live Together. ReadHowYouWant. p. 12. ISBN 978-1459625150.

- ^ Kern, Gary (2007). The Kravchenko Case: One Man's War on Stalin. Enigma Books. p. 287. ISBN 978-1929631735.

- ^ Murray and McCabe, p. 79.

- ^ a b c d e Meyer, p. 128.

- ^ Heydt, Bruce (February 2006). "Norman Rockwell and the Four Freedoms". America in WWII. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- ^ Journal, Greg Sukiennik, Manchester (July 11, 2018). "Arlington and Rockwell: A enduring relationship". Manchester Journal.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Norman Rockwell in the 1940s: A View of the American Homefront". Norman Rockwell Museum. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Solomon, p. 205.

- ^ a b c d e f g Solomon, p. 207.

- ^ Scholes, Robert (2001). Crafty Reader. Yale University Press. pp. 98–100. ISBN 0300128878.

- ^ Updike, John; Christopher Carduff (2012). Always Looking: Essays on Art. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 22. ISBN 9780307957306.

- ^ a b "Art: I Like To Please People". Time. Time Inc. June 21, 1943. Archived from the original on July 16, 2007. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- ^ Murray and McCabe, p. 35.

- ^ a b Murray and McCabe, p. 46.

- ^ Claridge, p. 307.

- ^ a b Westbrook, Robert B. (1993). Fox, Richard Wightman and T. J. Jackson Lears (ed.). The Power of Culture: Critical Essays in American History. University of Chicago Press. pp. 218–20. ISBN 0226259544.

- ^ Hennessey and Knutson, p. 100.

- ^ "Pining for Democracy: A Few Readings". The Scholar's Stage. November 10, 2018. Retrieved January 10, 2023.

- ^ Claridge, p. 309.

- ^ Murray and McCabe, p. 59.

- ^ Janda, Kenneth; Jeffrey M. Berry and Jerry Goldman (2011). The Challenge of Democracy. Cengage Learning. p. 213. ISBN 978-1111341916.

- ^ Eagle, Clarence Fanto, The Berkshire (July 28, 2024). "How and why did Norman Rockwell's iconic 'Freedom of Speech' painting become an internet meme? Museum leaders offer some answers". The Berkshire Eagle. Retrieved September 5, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McFarlane, Charles W. (July 3, 2024). "How Norman Rockwell's "Freedom of Speech" Painting Became the Internet's Soap Box". The New York Times. Retrieved September 5, 2024.

General and cited references

[edit]- Claridge, Laura (2001). "21: The Big Ideas". Norman Rockwell: A Life. Random House. pp. 303–314. ISBN 0-375-50453-2.

- Hennessey, Maureen Hart; Anne Knutson (1999). "The Four Freedoms". Norman Rockwell: Pictures for the American People. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. with High Museum of Art and Norman Rockwell Museum. pp. 94–102. ISBN 0-8109-6392-2.

- Meyer, Susan E. (1981). Norman Rockwell's People. Harry N. Abrams. pp. 128–133. ISBN 0-8109-1777-7.

- Murray, Stuart; James McCabe (1993). Norman Rockwell's Four Freedoms. Gramercy Books. ISBN 0-517-20213-1.

- Solomon, Deborah (2013). "Fifteen: The Four Freedoms (May 1942 to May 1943)". American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 201–220. ISBN 978-0-374-11309-4.

- Westbrook, Robert B. (1993). Fox, Richard Wightman and T. J. Jackson Lears (ed.). The Power of Culture: Critical Essays in American History. University of Chicago Press. pp. 218–20. ISBN 0226259544.

Further reading

[edit]- McFarlane, Charles W. (July 3, 2024). "How a Patriotic Painting Became the Internet's Soap Box". The New York Times. Retrieved July 4, 2024.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch