Manifesto of Futurism

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2023) |

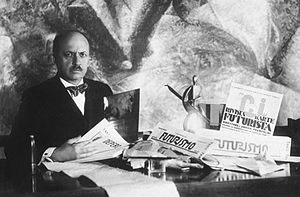

The Manifesto of Futurism (Italian: Manifesto del Futurismo) is a manifesto written by the Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, published in 1909.[1] In it, Marinetti expresses an artistic philosophy called Futurism, which rejected the past and celebrated speed, machinery, violence, youth, and industry. The manifesto also advocated for the modernization and cultural rejuvenation of Italy.

Publication

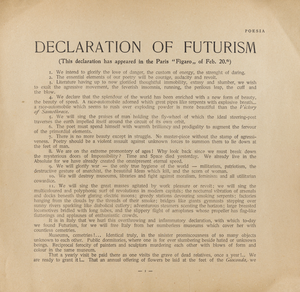

[edit]Marinetti wrote the manifesto in the autumn of 1908, and it first appeared as a preface to a volume of his poems, published in Milan in January 1909.[2] It was published in the Italian newspaper Gazzetta dell'Emilia in Bologna on 5 February 1909,[3] and then in French as Manifeste du futurisme (Manifesto of Futurism) in the newspaper Le Figaro on 20 February 1909.[4][5][6] The April 1909 issue of Marinetti's Poesia focused on the manifesto, and the Italian and French versions were reprinted in March 1912 alongside the English version.[7][8] In April 1909, the Madrid-based magazine Prometeo published the Spanish translation of the manifesto, which was translated by Ramón Gómez de la Serna.[9][10]

Contents

[edit]At the end of the 19th century, the Futurists challenged the limits of Italian literature (see articles 1, 2, and 3). Their response included the use of deliberate excesses to demonstrate the existence of a dynamic, surviving Italian intellectual class.

During this period, when industry was becoming increasingly important across Europe, the Futurists sought to affirm that Italy was not only present but also possessed industry and the power to participate in new experiences. They believed Italy would find the essence of progress in major symbols like the car and its speed (see article 4). While nationalism was never openly declared, it was evident in their work.

The Futurists argued that literature would not be overshadowed by progress; instead, it would absorb progress as part of its natural evolution. They believed that progress must manifest in this way because man, through it, would unleash his instinctive nature. Man was reacting against the potentially overwhelming force of progress, asserting his centrality. Man would harness speed, rather than be dominated by it (see articles 5 and 6).

Poetry would help man embrace the idea that his soul is part of this transformation (see articles 6 and 7), introducing a new concept of beauty rooted in the human instinct for aggression.

The sense of history could not be overlooked, as this was a pivotal moment when many things were evolving into new forms and content. However, man would be able to navigate these changes (see article 8), carrying with him the essence of what has existed since the beginning of civilization.

In Article 9, war is described as a necessity for the health of the human spirit, a form of purification that promotes and benefits idealism. The Futurists' explicit glorification of war and its "hygienic" qualities influenced the ideology of fascism. Marinetti remained active in fascist politics until he withdrew in protest against the focus on "Roman Grandeur," which had come to dominate fascist aesthetics.

Article 10 states: "We want to demolish museums and libraries, fight morality, feminism, and all opportunist and utilitarian cowardice." However, Futurism scholar Günter Berghaus argues that Marinetti's stance against "feminism" in Article 10 is unclear, especially when contrasted with his publication of works by women Futurists in the literary journal Poesia.[11]

Meaning

[edit]This manifesto was published well before the occurrence of the 20th-century events commonly associated with its potential meaning. However, the political movements underlying these events were already well-established and undoubtedly informed Marinetti's thinking, while his publication subsequently influenced them. Most notably, the rise of Italian Fascism, which the manifesto is widely seen as a precursor to, and Mussolini, who often quoted Marinetti.[12] At the time of its publication, the manifesto was frequently cited as an "imagining of the future" for some of these political movements, glorifying violence and conflict, and calling for the destruction of cultural institutions like museums and libraries.[13] For example, the Russian Revolutions of 1917, the first successfully sustained revolution of the type described in Article 11, echoed these ideas. The earlier, smaller-scale peasant uprisings known as the Russian Revolution, which led to the creation of a Russian constitution by the State Duma in 1906, occurred just before the manifesto's publication.

The founding manifesto did not include a positive artistic program, which the Futurists aimed to establish in their subsequent Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting (1914).[14] This commitment to a "universal dynamism" was intended to be directly represented in painting. In reality, objects are not separate from one another or their surroundings: "The sixteen people around you in a rolling motor bus are in turn and at the same time one, ten four three; they are motionless and they change places. ... The motor bus rushes into the houses which it passes, and in their turn, the houses throw themselves upon the motor bus and are blended with it."[15]

Women in Futurism

[edit]Several women were active in the Futurist movement and contributed to its manifestos. Benedetta Cappa worked in ceramics, glass, paint, and metal to explore the concept of aeropainting.[16] She also co-wrote the Manifesto of Tattilismo alongside her husband, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. The manifesto asserts that art is meant to be touched and experienced with the body.[17]

See also

[edit]- Futurist The Art of Noises Manifesto of Noise Music

- Futurist Painting: Technical Manifesto

- Du "Cubisme" Manifesto of Cubism

- Fascist Manifesto

- Art manifesto

References

[edit]- ^ Oxford Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art, Oxford University, pp. 253–256

- ^ Lynton, Norbert (1994). "Futurism". In Nikos Stangos, ed. Concepts of Modern Art: From Fauvism to Postmodernism. 3rd ed., London: Thames & Hudson. p. 97. ISBN 0500202680.

- ^ Paolo Tonini (2011). "I manifesti del Futurismo 1909–1945" (PDF). Edizioni del Arengario. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art, Oxford University, p. 253

- ^ Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. "I manifesti del futurismo". Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- ^ "Le Futurisme". 20 February 1909. No. 51. Le Figaro. Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- ^ "Manifesto of Futurism | British Library". www.bl.uk. 2023-09-28. Retrieved 2023-09-28.

- ^ Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso (April 1909). "Declaration of Futurism". Poesia. 5.

- ^ Andrew A. Anderson (2000). "Futurism and Spanish Literature in the Context of the Historical Avant-Garde". In Günter Berghaus (ed.). International Futurism in Arts and Literature. Vol. 13. Berlin; New York: Walter de Gruyter. p. 145. doi:10.1515/9783110804225.144. ISBN 9783110156812.

- ^ Kelly S. Franklin (Summer 2017). "A Translation of Whitman Discovered in the 1912 Spanish Periodical Prometeo". Walt Whitman Quarterly Review. 35 (1): 115–126. doi:10.13008/0737-0679.2267.

- ^ Berghaus, Günter (2010). Bentivoglio, Mirella; Zoccoli, Franca; Minciacchi, Cecilia Bello; Contarini, Silvia (eds.). "Futurism and Women: A Review Article". The Modern Language Review. 105 (2): 401–410. doi:10.1353/mlr.2010.0233. ISSN 0026-7937. JSTOR 25698701.

- ^ [p. 7, Private Eye, No. 1610, 3 November 2023]

- ^ "Futurism and Philosophy". Library of Congress.

- ^ "I Manifesti del futurismo, lanciati da Marinetti, et al, 1914".

- ^ "Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting". Unknown.nu. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- ^ Stewart, Jessica (2022-02-25). "Futurism: The Avant-Garde Art Movement Obsessed With Speed and Technology". My Modern Met. Retrieved 2024-04-25.

- ^ Baranello, Adriana (August 14, 2015). "Futurist Artist and Author Benedetta was Born on 14 August 1897". www.italianartsociety.org. Retrieved 2024-04-25.

External links

[edit]- Poesia (magazine) Volume 5, Number 6, April 1909 English, French and Italian version of the manifesto (foreword/short story present in Le Figaro version is not included)

- English translation of the manifesto from the appendix of James Joll, Three intellectuals in politics, 1960 (foreword/short story is included)

- Futurist manifestos, 1909–1933

- Félix Del Marle, Le Manifeste futuriste à Montmartre, Comoedia, 18 July 1913 (French)

- Giovanni Lista, Futurisme. Manifestes, proclamations, documents, L'Âge d'Homme, 30 November 1973

- "The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism" Archived 2009-01-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Baranello, Adriana, This day in history. Italian Art Society. Retrieved April 10. https://www.italianartsociety.org/2015/08/futurist-artist-and-author-benedetta-was-born-on-14-august-1897/

- Steward, Jessica (February, 25, 2022), Futurism: The Avant-Garde Art Movement Obsessed With Speed and Technology. My Modern Met. April, 12, 2024. https://mymodernmet.com/what-is-futurism/

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch