Garlic chive flower sauce

| Type | Dip |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | China |

| Region or state | Shaanxi province |

| Main ingredients | Garlic chive flower |

Garlic chive flower sauce (Chinese: 韭花酱; pinyin: jiǔhuā jiàng) is a condiment made by fermenting flowers of Allium tuberosum. It is used in Chinese cuisine (especially in Northwest China) as a dip for its fragrant, savory and salty attributes. The flower has a mild garlic flavor and aroma.[1][2]

History

[edit]

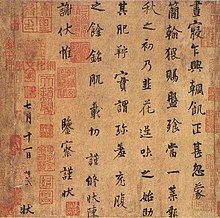

The condiment originated in China, where the plant was first cultivated for culinary purposes in the Zhou Dynasty.[3] The usage of garlic chives' flowers in a dipping sauce for mutton dates from the 8th or 9th century CE. In the Jiu Hua Tie, the fifth most important piece of Chinese calligraphy in semi-cursive script, Yang Ningshi (873–954)[4][5] recorded using garlic chive flowers to enhance the flavors of mutton:

当一叶报秋之初,乃韭花逞味之始,助其肥羜,实谓珍羞,充腹之馀,铭肌载切

— 杨凝式, 韭花帖

At the start of autumn, the chive flowers begin to become flavorful and can be used to enhance lamb flavors. This is a true delicacy that, apart from satiating hunger, gave a memorable experience.

A similar usage is described in written records from the later Qing Period.

The contemporary Chinese writer Wang Zengqi has described and commented on the custom of making garlic chive flower sauce in northern Chinese households, asserting that it originated in Northwest China. He has analyzed the Jiu Hua Tie from the perspective of a fellow writer and epicure; discussing the usage of the flower, he wrote:[6][7][verify translation]

It is the first time, and perhaps the only time, that garlic chive flowers made their presence in calligraphy. This piece, named after the flower, has characters intact and is as comprehensible as contemporary language, invoking a sense of familiarity. Though not encyclopedically knowledgeable, I have never seen the flower appear in literature, which is unfair for a delicacy so prevalent yet flavorful. [...]

Record is not given on how the garlic chives flowers are processed. But it appears that it is accompanied by mutton. [The piece mentioned the sentence] "助其肥羜", in which "羜" is five-month-old lamb, which is not necessarily what Yang had actually eaten, but more likely an allusion from the "既有肥羜" verse in Lumbering, Xiao Ya, Shi Jing. Beijingers cannot part from garlic chive flower sauce when eating instant-cooked mutton, a tradition [I] previously thought to have originated from Mongol or Western minorities, but it appears that it already existed during the Wudai period. Yang Ningshi lived in Shaanxi, and serving garlic chive flowers alongside mutton is a tradition that started near there also.

Garlic chive flowers in Beijing are ground and pickled when eaten, and are somewhat juicy in texture. It is good both as dipping for mutton and as a pickle alone.

— Wang Zengqi, 文人与食事:多年父子成兄弟, Chive Flowers

Preparation

[edit]

The condiment is made by fermenting grounded flowers of garlic chives in salt, sesame oil, and spices including Sichuan pepper, ginger, and garlic. After it is made, it can be stored for up to a year.[8] Different regions may vary in preference on production methods and the inclusion or exclusion of certain spices, but pickling a combination of predominant chive flowers and supplementary spices is common.[9][10]

Culinary uses

[edit]The condiment can be used as a dipping sauce for boiled mutton[6] and can also be a composite material for the dipping sauce of Chinese hot pot. It is used in small quantities and usually mixed with sesame paste or rice vinegar (among others) to avoid an overwhelmingly salty taste.[11][12]

References

[edit]- ^ "Don't Toss Those Purple Flowers: Chive Blossoms Add Flavor to Dishes". The Spruce Eats. Retrieved 2022-08-24.

- ^ "Garlic Chives, Allium tuberosum". Wisconsin Horticulture. Retrieved 2022-08-24.

- ^ "Delicious Recipes Using Garlic Chives". The Spruce Eats. Retrieved 2022-08-24.

- ^ "杨凝式 行书韭花帖 无锡博物馆藏". Chinese Calligraphy (12): 72–79. 2016.

- ^ Yu, Chen (June 28, 2003). "春畦雨后滋蔬甲 五代风流映韭花——谈传世的三本《韭花帖》". 上海文博论丛 (2): 53–55 – via National Digital Library of China.

- ^ a b Wang, Zengqi; 汪曾祺 (2016). Wen ren yu shi shi : duo nian fu zi cheng xiong di. Lang Wang, 汪朗 (Di 1 ban ed.). Shanghai Shi. ISBN 978-7-5426-5666-7. OCLC 987303957.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ 汪曾祺 (2013). Zuo fan. Wang zeng qi, 汪曾祺. Nan jing: Jiang su wen yi chu ban she. ISBN 978-7-5399-6376-1. OCLC 910465709.

- ^ "韭菜花酱的做法_韭菜花酱怎么做_菜谱_美食天下". Meishi China. Retrieved 2022-08-23.

- ^ "Leek Flower Sauce Recipe - Simple Chinese Food". Simple Chinese Food. Retrieved 2022-08-23.

- ^ De, Mu (June 30, 1987). "Production of Garlic Chive Flower Sauce". New Agriculture (Z1).

- ^ "韭菜的花能吃? 專家親授「韭花醬」營養更加分". tw.news.yahoo.com (in Chinese). 7 September 2020. Retrieved 2022-08-24.

- ^ Cai, Kehua (May 1, 1991). "韭菜花的加工腌制". Changjiang Vegetables (2): 40–46.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch