General Post Office, London

| General Post Office, London | |

|---|---|

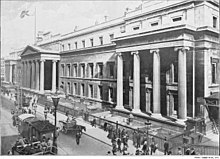

The 19th-century headquarters of the General Post Office in London | |

| |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival |

| Address | St. Martin's Le Grand |

| Town or city | London |

| Country | United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland |

| Coordinates | 51°30′56″N 0°05′49″W / 51.515550°N 0.096925°W |

| Construction started | May 1824 |

| Opened | 23 September 1829 |

| Demolished | 1912 |

| Client | General Post Office |

| Dimensions | |

| Other dimensions | 400 feet (120 m) long, 80 feet (24 m) deep |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Robert Smirke |

The General Post Office in St. Martin's Le Grand (later known as GPO East) was the main post office for London between 1829 and 1910, the headquarters of the General Post Office of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and England's first purpose-built post office.

Originally known as the General Letter Office,[1] the headquarters of the General Post Office (GPO) had been based in the City of London since the first half of the 17th century. For 150 years, it was in Lombard Street, before a new purpose-built headquarters, designed by Robert Smirke, was opened on the eastern side of St. Martin's Le Grand in 1829.[2] As well as functioning as a post office and sorting office, the building contained the main offices and facilities for the Postmaster General of the United Kingdom and other senior administrative officials.[3]

While externally attractive, Smirke's General Post Office suffered over the years from internal shortcomings due to ever-increasing demands on available space.[4] In the later part of the 19th century the GPO expanded into other buildings on St Martin's Le Grand, and further afield. After a new building was opened in nearby King Edward Street, Smirke's General Post Office was demolished in 1912.

Before the Great Fire of London

[edit]

Before the establishment of the General Post Office, post houses were set up in the City of London and elsewhere to provide horses for the conveyance of individuals or messages on behalf of the royal court. In 1526 a warrant was issued to the Court of Aldermen requiring a number of horses to be kept on hand if required for the King's Post; they in turn arranged with the innkeeper of the Windmill in Old Jewry to ensure that four horses would be kept available for those wishing to ride post, along with four more to be provided by the local hackney men (who kept horses for hire).[5] By the mid-17th century, there were separate post houses in London at the start of each of the post roads (which ran from London to different parts of the kingdom), including one in Bishopsgate for the route to Edinburgh, one at Charing Cross for the road to Plymouth and one in Southwark for the Dover road; these were invariably attached to licensed premises (where horses were customarily stabled). At this time the general administration of the Inland post and the Foreign post seems to have been carried out either from the houses of their chief officers, or else from one or other of the City's post houses.[5]

By 1653, though, a General Letter Office had been established 'at the Old Post House at the lower end of Threadneedle Street, by the Stocks'.[5] This was a substantial building, which provided accommodation as well as office space for a number of Post Office officials. It was, however, destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666; following which the business of the Post Office was carried on from a series of temporary offices in various locations.

General Post Office, Lombard Street

[edit]

In 1678, the General Post Office found a more permanent home in a mansion in Lombard Street, belonging to Sir Robert Vyner; (the Post Office initially rented the property, before finally purchasing it from the Vyner family in 1705).[6]

The Post Office in Lombard Street was built around a courtyard, open to the public and accessed from the street via an imposing gateway. Facing the gate across the courtyard was the sorting office, beneath which in the basement was the letter-carriers' office. On the left was the foreign letter office and on the right was the Board-room (which was attached to the official residence of the Postmasters General).[6] Elsewhere in the building accommodation was provided for clerks and other members of staff, who were at that time required to live on site owing to the need to be available when the post arrived, by day or by night.

By 1687, the Post Office had expanded to the south and west as far as Sherborne Lane, where an additional entrance was constructed.[5] The General Post Office remained in Lombard Street for a century and a half, during which time it continued to expand into neighbouring properties; however the increased employment of mail coaches towards the end of the 18th century caused difficulties as there was very little space for them to pull up and they were forced to queue in the narrow street.[7]

With the post office having this outgrown its premises in Lombard Street a site was sought for a new building.[8] The City of London and Westminster Streets and Post Office Act 1815 (55 Geo. 3. c. xci) authorised commissioners to identify a suitable location, and to pay compensation to the owners of properties on the site. A parcel of land on the east side of St. Martin's Le Grand was chosen; however the clearance and preparation of the densely-occupied site took several years, and it was only in May 1824 that the stones of the new building began to be laid.[9]

General Post Office, St Martin's Le Grand

[edit]

Smirke's new General Post Office opened on 23 September 1829. It was the UK's second purpose-built post office;[10] Dublin's GPO (completed in 1818 to a design by Francis Johnston and still in use) predates it.[11] The new Post Office was 'one of the largest public edifices now existing in the City of London' in 1829.[12]

Design and operation

[edit]The Post Office was built in the Grecian style with Ionic porticoes along the main (west) front, and was 389 feet (119 m) long and 130 feet (40 m) wide and 64 feet (20 m) high.[9] Above a basement storey of granite it was brick-built, but encased on all sides in Portland stone.[13] The building's main façade had a central hexastyle Greek Ionic portico with a pediment, and two tetrastyle porticoes without pediments at each end. Above the main entrance was a large chiming clock (by Vulliamy) with an external and internal dial, which governed timekeeping within the building.[14]

Mail coaches and mail carts

[edit]

The General Post Office was built in the era of the mail coach, with a driveway leading around the back of the building to a courtyard on the north side where the coaches would assemble. Each night, from all around the country, London-bound mail coaches would set off at different times, so as to arrive at St Martin's Le Grand between 5 and 6 o'clock in the morning;[9] the mail was then unloaded and sorted, ready for delivery at 8am. Then in the evening, the coaches were loaded with sacks of mail destined for the provinces. The daily departure of the mail coaches regularly attracted crowds of spectators.[15] At 8pm, Monday-Saturday, all the coaches would set off in different directions from St Martin's Le Grand; each would follow its own set route, progressively dropping off mail bags at every post town on the way to its final destination.[9] Mail for destinations overseas was mostly taken to Falmouth or Dover to be loaded on to packet boats.

In between the arrival and departure of the mail coaches, red-painted mail carts would come and go all through the day, collecting and delivering mail within the London postal area. Working alongside the mail carts were riding-boys, who would carry sacks of mail on horseback. (Usually aged between 13 and 16, they would often go on to drive the mail carts when they were older).[16] The carts and riding-boys would collect mail from, and deliver it to, 'receiving houses' all round London. By 1850, the London District Office was carrying out ten collections and deliveries a day, six days a week, in the central London area (within a 3-mile radius of St Martin's Le Grand) and between three and five collections in the suburbs (within a 12-mile radius).[17] There were no deliveries or collections of any kind on Sundays.

The Grand Public Hall

[edit]

Behind the central portico of the Post Office was a Grand Public Hall, forming a public thoroughfare from St Martin's-le-Grand to Foster Lane; it measured 80 ft (24 m) by 60 ft (18 m) and had aisles on either side separated from the centre by rows of ionic columns.[18] Members of the public could post letters and other items from inside the hall through boxes in the wall, from where they would fall into hoppers and be loaded into trolleys to be taken to the sorting offices beyond. There were also windows and offices where payments could be made.[16] Each day, shortly before 6pm (the deadline for the Inland post), there would always be a last-minute rush of people with letters and newspapers to post; the windows above the slots were then opened to facilitate delivery, but were always closed on the sixth stroke of the clock (after which items could be posted at the 'late' window, but only with payment of a surcharge). Charles Dickens described the daily 6 o'clock rush in a descriptive and detailed article on the workings of the Post Office in 1850.[16]

The Grand Public Hall divided the building in two: personnel to the south dealt mainly with the London post, while those to the north dealt mainly with the national post. (Up until 1855, two separately-constituted corps of letter-carriers worked from the two separate halves of the building: the blue-liveried London District carriers on the one hand, and the red-uniformed General Post carriers on the other.)[13] A tunnel and conveyor system beneath the Grand Public Hall linked the two halves of the building.[18]

The principal offices

[edit]In 1829, the three 'great divisions' of the General Post Office were:[12]

- The Inland Office (also called the General Post), which was responsible for conveying letters between London and other post towns (across the rest of the UK and the wider British Empire).

- The Foreign Office, responsible for the passage of letters to and from other overseas destinations (including dealing with foreign postal services as required).

- The London District Office (also called the Two-penny Post) for sending letters within the London area (successor to the London Penny Post established by William Dockwra in 1680).

The Inland Office

[edit]The Inland Office was based in the northern half of the building. Immediately adjacent to the Public Hall on this side were the rooms for receiving newspapers, inland letters and ship letters posted by members of the public through the slots; beyond these were large halls for the sorting, marking and despatching of items, the largest of which was the Inland Letter Office.

The Inland Letter Office, centrally-placed within the northern half of the building, was a sizeable chamber measuring 90 ft (27 m) by 56 ft (17 m).[19] It was here that letters for and from the provinces were received, stamped, counted and sorted. The room was a hive of activity at the start of the day, when coaches arrived from around the country laden with letters for London; and at the end of the day, when the letters from London were sorted and stamped before being bagged, and loaded on coaches for delivery to provincial post offices all round the country.[9]

Alongside the Inland Letter Office to the west was the Letter-carriers' Office (103 ft (31 m) by 35 ft (11 m)), with elegant iron galleries and spiral staircases.[20][21] Here, each morning, the letter-carriers would sort their designated letters into different 'walks' before setting off to deliver them. Letters destined for addresses in central London were delivered by the Inland department's own letter-carriers, while those for the suburbs were sent on the under-floor conveyor to the London District office for delivery.[16] In the evening, the Letter-carriers' Office was used for the sorting of large numbers of newspapers for overnight despatch).[22]

On the east side of the Inland Letter Office (with an entrance from Foster Lane) was a large vestibule, where the incoming and outgoing letter bags were received from and despatched to the mail coaches. Before leaving the building they were placed in the custody of the Mail-Guards, who were armed and accompanied the bags on the coaches to ensure safe delivery. The Mail-Guards had rooms, including an armoury, in the basement of the building.[9]

Other rooms in the northern half of the building included the Dead Letter Office, the Missing Letter Office and the Blind Office (for deciphering illegible addresses). The Superintending President of the Inland Office had his office at the northernmost end of the building, overlooking the yard.[22] Connected with the Inland department was the Ship Letter Office, which transported mail by sea to certain destinations using privately-owned ships (at a cheaper rate than the Government-owned packet boats, which were overseen by a different office in the other half of the building). Likewise the West India Office and the North American Office, which were adjacent to the Inland Letter Office and managed the transport of mail to and from parts of the British Empire.[9]

The Foreign Office

[edit]Adjoining the Public Hall on the south side of the building was the Foreign Letter Office, from which letters were sent to a great variety of (non-British) overseas destinations by way of the packet service. Its clerks were provided with overnight accommodation on the second floor, so as to be available for duty whenever letters might arrive from overseas, day or night. The Foreign department also maintained its own team of letter-carriers at this time, to deliver mail to addresses in central London.

The London District Office

[edit]Also in the southern half of the building were the offices of the London District Office or 'Two-penny Post', which occupied three large rooms to the east of the Foreign Office (the receiving room, sorters' office and carriers' office).[12] Measuring just 46 ft (14 m) by 24 ft (7.3 m), the London District sorting office was considerably smaller than its Inland counterpart.[12]

The London District Office had its own entrance on the east side, by which letter bags were conveyed to and from the waiting mail carts and riding-boys. There was also stabling provided on this side of the building for a limited number of horses.[16] The London District office operated in a similar way to the Inland office, but on a more constant basis as letters were received and despatched at regular times all through the day. From St Martin's Le Grand the letters went out in sealed bags to the receiving houses, where letter-carriers would be on hand to deliver them (at this time the London District Office had over a hundred receiving houses across London, and the Inland Office around 50).[23]

Other offices

[edit]The Receiver General and the Accountant General also had their offices on the south side of the Public Hall; [9] the poste restante office for London was also located there. A corridor next to the main entrance on the south side led to a 'grand staircase', which provided access to rooms on the first floor (principally the Board Room and the Secretary's office).[12] The Secretary of the Post Office, who was the chief administrative officer of the GPO, was also provided with an official residence at the south-west corner of the building.[24]

Changes and developments

[edit]Almost as soon as it had opened, the building was found to be short of space.

1830s

[edit]As early as 1831, a gallery was inserted into the main Inland sorting office to provide extra capacity.[16] In 1836, following the death of Francis Freeling, the Secretary's residence in the south-west corner of the building was given over to office use.

Within a decade of the building's opening, rail had replaced road as the principal means of distribution around the country, consigning the mail coach to history.[7] The Inland Office now used horse-drawn mail-vans to convey sacks of letters to the railway termini where they were loaded on to trains or Travelling Post Offices.[13]

1840s

[edit]Following the introduction of the uniform penny post in 1840, the number of letters passing through the building increased substantially.[23] To help with the increased volume of post, a new sorting office was built[25] immediately above the old one, 'suspended from a strong arched iron girder roof by iron rods' (a solution which, though ingenious, left the principal room below entirely deprived of natural light).[16] At around the same time a transit system was installed whereby 'two endless chains, worked by a steam-engine, carry, in rapid succession, a series of shelves, each holding four or five men and their letter-bags, which are thus raised to various parts of the building'.[18] The upper room took over the function of the dual-purpose letter-carriers' office / newspaper sorting office, allowing the inland letter office to expand into the vacated space below.[16][26]

The Money Order Office had been established in 1838, in two small rooms at the north end of the building. In the 1840s it operated from a large room adjoining the Public Hall on the south side near the main entrance; but it soon outgrew these premises and in 1846 the Money Order Office was provided with new premises (designed by Sydney Smirke) just across the road at No. 1 Aldersgate Street.

At around the same time the Foreign Letter Office was made an adjunct to the Inland Letter Office (both administratively and physically): an arch was inserted in the north wall of the Inland Office beyond which several rooms were knocked together to create a new sorting office for the 'Colonial and Foreign Division' (measuring 30 ft (9.1 m) by 18 ft (5.5 m)), which was linked by way of a mail-hoist to the Ship-letter Office above.[16]

On the south side of the building, the London District office then expanded into spaces vacated by the Foreign Office; before long the London District sorting office had more than doubled in size.[16]

1850s

[edit]Reforms undertaken in the 1850s, when the Duke of Argyll was Postmaster General and Rowland Hill was Secretary, helped ease the overcrowding somewhat: the erstwhile separate operations of the Inland, Foreign and London District offices were brought together to form a single Circulation Office, overseen by the Controller of the London Postal Service. The three separate corps of letter-carriers were also amalgamated, along with their respective receiving houses. As part of these reforms, London was subdivided in 1856 into ten postal districts, each with its own district office able to receive and distribute its own mail (whereas previously all London's letters had had to pass through St Martin's Le Grand for sorting and redistribution).[13] The districts were named according to their compass bearing in relation to St Martin's Le Grand (a nomenclature which is preserved in London's postcode designations).

1860s

[edit]

Nevertheless the ongoing expansion of the work of the Post Office meant that the building was soon once again occupied well beyond its intended capacity; The Times reported in 1860 that "rooms have been overcrowded, closets turned into offices, extra rooms hung by tie rods to the girders of the ceiling".[4] Work requiring bright light was conducted in poorly illuminated areas, odours spread from the lavatories to the kitchens, while a combination of gas lighting and poor ventilation meant that workers often felt nauseous.

From 1868, the GPO experimented with the services of the London Pneumatic Despatch Company, which operated a pneumatic tube from Euston railway station for the delivery of mail, but the experiment was unsuccessful and terminated in 1874.

In 1870, with space in the building remaining at a premium, the Grand Public Hall was closed and converted into another additional sorting room; slots were then installed under the portico for members of the public to post their letters.[8] As part of these alterations a new upper floor was inserted along the double-height length of the hall to provide more space for the sorting of newspapers.[27]

Additional buildings

[edit]GPO West

[edit]

In 1874, a new building, designed by James Williams, was opened on the western side of St. Martin's Le Grand: GPO West.[28] It had originally been designed to house the main administrative offices and senior GPO officials on the lower two floors, and the Post Office Savings Bank on the upper two floors (leaving the old building to focus on letters and newspapers);[29] but following the nationalisation of the UK's electrical telegraph companies in 1870, the upper floors were given over to telegraphic equipment and the building became known as the Central Telegraph Office (CTO).[30] The instrument rooms employed nearly a thousand people at a time sending and receiving messages; the basement served as a battery room, with space for 40,000 cells.[23]

As well as using wire connections, the CTO was linked to 38 different branch offices around central London using a network of pneumatic tubes (inherited from the Electric Telegraph Company and subsequently expanded). Three steam engines in the north courtyard powered the entire system (generating a pressure and vacuum for sending and receiving), fed by four boilers in the south courtyard.[31]

Not long after GPO West opened still more space was needed: in 1882 it expanded to the west, being linked to an adjacent building via bridges across Roman Bath Street; and in 1884 an additional storey was built on the top.[32] In 1892, it was said to be the largest telegraph station in the world.[31] By this time the Central Hall on the ground floor had been converted to serve as the main pneumatic tube room, while the second, third and fourth floors were occupied by the instrument rooms of the electric telegraph systems. In 1896, the headquarters of the GPO's new Telephone section was established in GPO West, in rooms vacated by the senior officials and administrative staff (who had recently moved into their own separate building).[33]

GPO South

[edit]Meanwhile, in 1880, a new building opened a quarter of a mile to the south in Queen Victoria Street; it initially accommodated the Post Office Central Savings Bank.[32] In 1890, it expanded into another building immediately to the north, to which it was linked by a bridge over (and tunnel under) Knightrider Street. In the early 1900s, the savings bank moved out to West Kensington, while the building (which had by then been given the designation GPO South) became London's first telephone exchange and offices for the GPO's London Telephone Service.

GPO North

[edit]

In 1895, GPO North was opened immediately to the north of GPO West (and connected to it across Angel Street by a second-floor footbridge), as the GPO continued to expand.[34] Known as Post Office Headquarters (PHQ), it was designed by Henry Tanner to house the Postmaster General and the GPO's administrative departments (the Secretary's Office, the Accountant General's Office, the Solicitor's Office, etc.). To make way for the new building the old Bull and Mouth Inn was demolished, where at one time the mail coaches had been harnessed to their horses ready to collect the mail from the Post Office across the road.[7]

The building had a large courtyard at its centre, entered via covered passageways at either end. The outer arched entrances were topped with sculptural likenesses of two recent Postmasters General: H. C. Raikes (facing St Martin's Le Grand) and Arnold Morley (overlooking King Edward Street); while the equivalent arches on the courtyard side had representations of David Plunket and George Shaw Lefevre (recent First Commissioners of Works).[30] The Postmaster General had his office on the ground floor, on the King Edward Street side; the Permanent Secretary and his staff were on the first floor. Beneath the courtyard was a large basement designed to hold the Post Office archives.[30]

GPO East

[edit]

Meanwhile, Robert Smirke's original General Post Office (which, to avoid confusion, had been renamed GPO East) continued to deal with letters and newspapers. When the parcel post was being introduced 1882, a sorting office was swiftly constructed for it by James Williams at basement level, extending into the Post Office yard;[35] then in 1889 the parcel-post sorting office was relocated to Mount Pleasant.[36] In 1893 an additional storey was added to the top of GPO East.[37]

Nevertheless, the 1896 report of the Tweedmouth Committee on Post Office Establishments declared the building to be 'incommodious, insanitary and overcrowded'.[38] The following year it was decided 'to reconstruct the building within the present outer walls'.[39] To enable the rebuilding, the Inland and Newspaper sections of the General Post Office were transferred in 1900 to a new building on the Mount Pleasant site, leaving GPO East to focus on the sorting of London and Foreign correspondence.[40] (At the same time, double-aperture pillar boxes began to be installed in central London, with one side for 'London and Abroad' and the other for 'Country' letters, in line with these new arrangements).[41]

In 1900, the Central London Railway was opened, with the nearest station to St. Martin's Le Grand being named Post Office. (Subsequently, in 1937, it was renamed St Paul's).

Demolition and replacement

[edit]

In 1905, King Edward VII laid the foundation stone of a new building on King Edward Street, immediately to the west of GPO North (and designed, as the latter had been, by Henry Tanner). Opened as the King Edward Building (KEB) in 1910, it was envisaged as a replacement for Smirke's GPO East, housing the main sorting offices for London (EC district) and the Foreign Section, as well as serving as London's principal public post office.[42]

With the opening of the new King Edward Building, the original Smirke building was closed in 1910;[43] two years later it was demolished.[2] The intention had been to construct a new 'GPO East' on the site, to accommodate the GPO's still-expanding administrative staff; but although plans were drawn up these never came to fruition, and the land was eventually sold in 1923.[44]

Aftermath

[edit]

The St Martin's Le Grand area remained a hub for London's postal services well into the second half of the twentieth century.[3] In organisational terms, the General Post Office became The Post Office in 1969, changing from a Government department to a statutory corporation.

In the mid-1920s, several steel-framed office blocks were built on the site of Smirke's demolished 'GPO East' by the newly-formed St Martin's Le Grand Property Group, and let (for the most part) to banks and manufacturing firms. Damaged during the war, they were subsequently rebuilt and in 1947 two of the blocks (Armour House and Union House) were let to the GPO on a 42-year lease.[45] Subsequently a third block (Empire House) was added; all three remained in Post Office use until the late 1980s.[46]

GPO West continued to operate as the Central Telegraph Office (CTO); it also housed the Engineering Department.[48] It was damaged by an aerial bomb dropped by a zeppelin during the First World War, which disabled the inland telegraph system for several hours.[49] During the Second World War, GPO West was twice severely damaged by incendiary bombs: first during the "Second Great Fire of London" on 29 December 1940, when the building was completely gutted, and then again in March 1942 (after the building had been repaired the previous year); it was subsequently rebuilt and restored to use, having been reduced in height from six storeys to two.[50] In 1962, the Central Telegraph Office was relocated and GPO West went on to serve as overflow office accommodation for Post Office Headquarters staff; however it was later deemed unsafe and was demolished in 1967.[32] The BT Centre (until 2021 the headquarters of BT Group) now stands on the site (BT was originally formed from the Post Office Telecommunications division). A plaque on the side of the BT Centre records that 'From this site Guglielmo Marconi made the first public transmission of wireless signals on 27 July 1896'.[3]

GPO South, having been converted into a telephone exchange, continued to expand; having been rebuilt in 1933, it is now known as the Faraday Building.

GPO North continued to serve as Post Office Headquarters (PHQ) until 1984, when the headquarters division moved to 33 Grosvenor Place. The building was subsequently sold to Nomura Holdings who reconstructed it internally (though the old façade was retained) and renamed it Nomura House.[51]

The King Edward Building remained in use until the mid-1990s. Since 1927, it had been served by the Post Office Railway, which provided a subterranean mail transport link between several different district and sorting offices. For much of the century KEB had offered a counter service 24 hours a day, but it closed to the public in April 1994.[51] It then continued to operate as the Royal Mail City and International Office until July 1996 when these functions were transferred to Mount Pleasant Sorting Office. Lastly, the National Postal Museum (which had opened within the building in 1966) closed in 1996.[32] The building was sold the following year.

The demolition of Smirke's 1829 General Post Office was not unopposed, and there were moves at the time to salvage the central portico and pediment and rebuild them elsewhere (one suggested location being Shadwell Park).[2] These ideas came to nought, however,[44] and today one of the only surviving fragments of the building is an Ionic capital from the right-hand side of the portico: this five-ton piece was presented to Walthamstow Urban District Council and is sited in Vestry Road.[52] Other Ionic capitals from the portico found their way into the gardens at Hyde Hall, Sawbridgeworth, where they served as flower pots.[53]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hibbert, Christopher; Weinreb, Ben (2008). The London Encyclopaedia. p. 660.

- ^ a b c "The Old General Post Office". The Architectural Review. XXXII (190): 174. September 1912.

- ^ a b c "Changing Architecture of London's Post Office Quarter". The Postal Museum. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ a b Perry, C R (1992). The Victorian Post Office: The Growth of a Bureaucracy. The Boydell Press. p. 4.

- ^ a b c d Greenwood, Jeremy (August 1973). "The Location of the London Head Office and Post Houses 1526-1687" (PDF). London Postal History Group Notebook (13): 3–5.

- ^ a b Joyce, Herbert (1893). The History of the Post Office from Its Establishment Down to 1836. London: Richard Bentley & Son. pp. 46–48.

- ^ a b c Bennett, Edward (1912). The Post Office and its Story. London: Seeley, Service & Co. Ltd. pp. 43–56. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ a b "St Martin's-le-Grand in 1892". St Martin's-le-Grand: The Post Office Magazine. III (9): 95–96. January 1893.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "The History and present State of the Post Office". Monthly Supplement of the Penny Magazine of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. III (117): 33–40. January 1834.

- ^ Brandwood, Geoff, ed. (2010). Living, Leisure and Law: Eight Building Types in England 1800–1914. Spire Books. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-904965-27-5.

- ^ Ferguson, Stephen (2014). The GPO - 200 Years of History. Mercier Press. ISBN 9781781172773.

- ^ a b c d e "The New Post Office". The Gentleman's Magazine. XCIX: 297–301. October 1829.

- ^ a b c d Lewins, William (1864). Her Majesty's Mails: an Historical and Descriptive Account of the British Post-office. London: Sampson Low, Son, and Marston. pp. 165–213.

- ^ "General Post-Office, St. Martin-le-Grand". The Illustrated London News. II (54): 319–320. 13 May 1843.

- ^ Crawford, David (1990). British Building Firsts: A Field Guide. Newton Abbott: David & Charles. p. 125.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Dickens, Charles (September 1850). "Mechanism of the Post Office". The Eclectic Magazine: 74–95.

- ^ Lettis, J. W. (1851). The Post Office Guide. London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans. p. 29.

- ^ a b c Timbs, John (1855). "Post-Office". Curiosities of London. London: David Bogue. pp. 626–628.

- ^ "Post Office". Encyclopaedia Britannica (vol. XVIII) (7th ed.). Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black. 1842. pp. 486–497.

- ^ Summerson, John (1991). Architecture in Britain 1530–1830 (8th ed.). Pelican Books. p. 473.

- ^ image

- ^ a b "The General Post Office - (By Authority)". The Illustrated London News. IV (112): 400–402. 22 June 1844.

- ^ a b c Tegg, William (1878). Posts and Telegraphs past and present. London: William Tegg & Co. pp. 47–53.

- ^ "The Old Home of the Post Office". St Martin's-le-Grand: The Post Office Magazine. I (2): 78–83. January 1891.

- ^ Image, 1846

- ^ Image, c.1900

- ^ Seventeenth Report of the Postmaster General on the Post Office. London: H. M. Stationery Office. 1871. p. 22.

- ^ "London General Post Office (GPO West)". British Post Office Buildings and Their Architects : an Illustrated Guide. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ "The General Post Office North". St Martin's-le-Grand: The Post Office Magazine. I (2): 126–127. January 1891.

- ^ a b c "London General Post Office (GPO North)". British Post Office Buildings and Their Architects : an Illustrated Guide. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ a b "The Pneumatic System of London". St Martin's-le-Grand: The Post Office Magazine. II (6): 81–88. April 1892.

- ^ a b c d Perry, Andrew. "The Post Office & King Edward Building" (PDF). Great Britain Philatelic Society. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ "Post Office Improvements in 1896". St Martin's-le-Grand: The Post Office Magazine. VII (26): 195–197. April 1897.

- ^ Report of the Postmaster General on the Post Office. Vol. 43–51. Great Britain: Post Office. 1897.

- ^ Baines, F. E. (1895). Forty Years at the Post Office (vol. ii). London: Richard Bentley and Son. p. 133.

- ^ Fry, Herbert (1892). London - Illustrated by Twenty Bird's-eye Views of the Principal Streets. London: W. H. Allen and Co. Ltd. pp. 162–163.

- ^ "The Seamy Side". St Martin's-le-Grand: The Post Office Magazine. III (10): 202. April 1893.

- ^ "The Tweedmouth Committee's Report". St Martin's-le-Grand: The Post Office Magazine. VII (26): 211–213. April 1897.

- ^ Forty-fourth Report of the Postmaster General on the Post Office. London: HMSO. 1898. p. 24.

- ^ Forty-seventh Report of the Postmaster General on the Post Office. London: HMSO. 1901. p. 3.

- ^ "Dual Aperture". The Letter Box Study Group. Retrieved 30 December 2024.

- ^ "London General Post Office (King Edward Building)". British Post Office Buildings and Their Architects : an Illustrated Guide. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ Crawford, David (1990). British Building Firsts: A Field Guide.

- ^ a b Campbell-Smith, Duncan (2011). Masters of the Post: The Authorized History of the Royal Mail. London: Penguin Books.

- ^ "St Martin's Le Grand Property". Investors Chronicle. 210: 22. 7 October 1960.

- ^ "INFORMATION SHEET NO 9: Headquarters of the Post Office" (PDF). Great Britain Philatelic Society. Post Office Archives 1988. Retrieved 25 May 2023.

- ^ "Fleet Building". Lightstraw UK: making clear sense of telecommunications history. Allen Lane. Retrieved 2 January 2025.

- ^ Muirhead, Findlay, ed. (1922). The Blue Guides: London and its Environs (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan and Co. Ltd. p. 225.

- ^ photo

- ^ "The Closing of the C.T.O." Post Office Electric Engineers Journal. 54 (3). October 1961. Retrieved 9 January 2025.

- ^ a b Weinreb, Ben; Hibbert, Christopher, eds. (1993). "Post Office". The London Encyclopaedia (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. p. 634.

- ^ Pevsner, Nikolaus; Cherry, Bridget (2005). The Buildings of England, London. Vol. 5.

- ^ Pevsner, Nikolaus (1977). The Buildings of England: Hertfordshire (Second ed.). New Haven & London: Yale University Press. p. 213.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to General Post Office (1829 building) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to General Post Office (1829 building) at Wikimedia Commons

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch