Ground (Dzogchen)

In Dzogchen, the ground or base (Tibetan: གཞི, Wylie: gzhi) is the primordial state of any sentient being. It is an essential component of the Dzogchen tradition for both the Bon tradition and the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism.[2][3] Knowledge of this ground is called rigpa.

Explication

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Tibetan Buddhism |

|---|

|

A key concept in Dzogchen is the 'basis', 'ground' or 'primordial state' (Tibetan: གཞི་ gzhi), also called the general ground (སྤྱི་གཞི་ spyi gzhi) or the original ground (གདོད་མའི་གཞི་ gdod ma'i gzhi).[4] The basis is the original state "before realization produced buddhas and nonrealization produced sentient beings". It is atemporal and unchanging and yet it is "noetically potent", giving rise to mind (སེམས་ sems,), consciousness (ཤེས་པ་ shes pa), delusion (མ་རིག་པ་ marigpa) and knowledge (རིག་པ་་rigpa).[5] Furthermore, Hatchell notes that the Dzogchen tradition portrays ultimate reality as something which is "beyond the concepts of one and many."[6]

Thus in Dzogchen, the basis is a pure empty consciousness which is what needs to be recognized to achieve awakening. According to Smith, The Illuminating Lamp declares that in Ati Yoga, pristine consciousness is a mere consciousness that apprehends primordial liberation and the generic basis as the ultimate."[5] In other words, spiritual knowledge in Dzogchen is recognizing one's basis.

Since the basis transcends time, any temporal language used to describe it (such as "primordial", "original" and so on) is purely conventional and does not refer to an actual point in time, but should be understood as indicating a state in which time is not a factor. According to Smith, "placing the original basis on a temporal spectrum is therefore a didactic myth."[7]

The basis also is not to be confused with the "all-basis" (Tib. ཀུན་གཞི་ kun gzhi) or with the fundamental store consciousness (Tib. ཀུན་གཞི་རྣམ་པར་ཤེས་པ་ kun gzhi rnam par shes pa), since these are both samsaric modes of consciousness.[8] Other terms used to describe the basis include unobstructed (མ་འགགས་པ་ ma 'gags pa), universal (ཀུན་ཁྱབ་ kun khyab) and omnipresent.[9]

The basis is also associated with the term Dharmatā, defined as follows: "Dharmatā, original purity, is free from all proliferation. Since it is unaffected by ignorance, it is free from all obscurations."[10] According to Smith, describing the basis as “great original purity” (ཀ་དག་ཆེན་པོ་ ka dag chen po) is the only description which is held to be flawless according to various Dzogchen Tantras.[10]

The basis is also associated with the primordial or original Buddhahood, also called Samantabhadra, which is said to be beyond time and space itself. Hence, Buddhahood is not something to be gained, but it is an act of recognizing what is already immanent in all sentient beings.[11] This view of the basis stems from the Indian Buddha-nature theory according to Pettit.[12] Tibetan authors like Longchenpa and Jigme Lingpa specifically linked the Dzogchen view of the basis with Buddha-nature or sugatagarbha (especially as it is found in the Ratnagotravibhāga).[13]

In Vimalamitra

[edit]In the Great Commentary of Vimalamitra (8th century), the basis is defined as "one’s unfabricated mind" (rang sems ma bcos pa). As Smith notes, this indicates how the basis is not some transpersonal entity.[14] [failed verification] The basis is therefore not defined as being "one thing" (i.e. monism, Brahman etc.), since there exists the production of diversity. Regarding this, The Realms and Transformations of Sound Tantra states: "Other than compassion arising as diversity, it is not defined as one thing."[15] The Illuminating Lamp commentary explains the pristine consciousness of the basis thus:

In Ati, the pristine consciousness — subsumed by the consciousness that apprehends primordial liberation and the abiding basis as ultimate — is inseparable in all buddhas and sentient beings as a mere consciousness. Since the ultimate pervades them without any nature at all, it is contained within each individual consciousness.[5]

In Longchenpa

[edit]The Tibetan master Longchenpa (1308–1364) describes the basis as follows:

the self-emergent primordial gnosis of awareness, the original primordially empty Body of Reality, the ultimate truth of the expanse, and the abiding condition of luminously radiant reality, within which such oppositions as cyclic existence and transcendent reality, pleasure and suffering, existence and non-existence, being and non-being, freedom and straying, awareness and dimmed awareness, are not found anywhere at all.[16]

Moreover, Longchenpa notes that "ground" should be understood as a "groundless ground", which seems to be a ground and is posited as so only from a relative perspective, while in the true nature of reality it is empty of being a ground. Because it has no intrinsic nature, and from the a relative perspective the experiences of saṃsāra and nirvāṇa seem to arise from it, it is referred to as the ground:

[D]ue to supporting all phenomena of saṃsāra and nirvāṇa, it is the abiding reality called "the ultimate universal ground"; it is unconditioned and abides as the great primordial purity. Moreover, it supports the phenomena of saṃsāra—karma and afflictive emotions—in the manner of a non-support, as the sun and space support cloud formations, they abide within its state without contact or connection with the basis. In reality, since there is no intrinsic nature, support and supported are not established; since it appears as such it is so designated [as the support].[a]

In Namkhai Norbu

[edit]Namkhai Norbu (1938–2018) writes that the term basis denotes "the fundamental ground of existence, both at the universal level and at the level of the individual, the two being essentially the same." This basis is "uncreated, ever pure and, self-perfected, it is not something that has to be constructed," however it "remains hidden to the experience of every being affected by the illusion of dualism."[17] Jean Luc-Achard defines the basis as "the actual, authentic abiding mode of the Mind."[18] According to Achard, Dzogchen tantras define the basis as "Great Primordial Purity" (ka dag chen po). The Tantra of the Beautiful Auspiciousness (bKra shis mdzes ldan gyi rgyud) defines this as "the state abiding before authentic Buddhas arose and before impure sentient beings appeared."[18]

Three aspects

[edit]

In the Longchen Nyingtik tradition, the ground has three qualities or aspects, also called the "three wisdoms". Each one is paired with one of the three bodies of the Buddha and with one of the three jewels (indicating that these are fully included in each sentient being). Norbu notes that "these three aspects are interdependent and cannot be separated from each other,"[20] just like the various qualities of a mirror are all essential to the existence of a mirror. The three aspects of the basis are:[21][22][23][24]

- Essence (Tib. ངོ་བོ་, ngowo; Wyl. ngo bo, Skt. svabhāva). It is defined as original purity (Tib ka dag, "ever-pure"). Ka dag is a contraction of ka nas dag pa, "pure from ka" (ka is the first letter of the Tibetan alphabet) which is also glossed as pure from the beginning (thog nas dag pa).[4] In this context, purity (Skt. śuddha) refers to emptiness (śunyata, stong pa nyid), which in Dzogchen is explained in a similar way to how emptiness is explained in Madhyamaka (as being free from the extremes of nihilism and eternalism).[4] The "Essence" is also associated with the Dharmakaya and the Buddha. Namkhai Norbu explains this as the fact that all phenomena are "essentially void, impermanent, only temporarily existing, and all 'things' can be seen to be made up of other things."[25] He compares this aspect with the emptiness which allows a mirror to take on any image.

- Nature (Tib. རང་བཞིན་, rangshyin; Wyl. rang bzhin, Skt. prakṛti) is defined as "Natural Perfection" (Tib. lhun grub, Skt. anābhoga), also translated "spontaneous presence" or "spontaneous accomplishment".[23] This is the noetic potentiality of the basis. According to Norbu, this aspect refers to the continuous manifestation or appearance of phenomena and can be illustrated by comparing it to a "mirror's capacity to reflect."[25] Sam van Schaik explains this as "a presence that is spontaneous in that it is not created or based on anything" as well as "the luminous aspect of the ground".[26] Natural Perfection is also used interchangeably with the aspect of "luminosity" ('od gsal, Skt. prabhāsvara).[27] The Nature of the basis is also associated with the Dharma and the Saṃbhogakāya. Longchenpa explains that there are "eight gateways of spontaneous presence". According to Hatchell the first six gateways are "the essential forms that awareness takes when it first manifests: lights, Buddha-bodies, gnosis, compassion, freedom, and nonduality," while the final two gateways "are viewpoints from which the first six are perceived" and are the gateways to purity (i.e. nirvana) and impurity (samsara) which are associated with self-recognition/integration and non-recognition/duality (also called "straying", 'khrul pa).[28]

- Compassion (Tib. ཐུགས་རྗེ་, tukjé, Wyl. thugs rje, Skt. karuṇā), also sometimes translated as "Energy". It is also called the "manifest ground" (gzhi snang) or the "ground of arising" ('char gzhi).[26] Norbu compares this manifest aspect of the basis to the particular appearances that are reflected in a mirror. This aspect is also defined in the Illuminating Lamp as: "Thugs is the affection (brtse ba) in the heart for sentient beings. Rje is the arising of a special empathy (gdung sems) for them."[29] Smith explains this aspect as referring to the unity of clarity and emptiness.[21] Clarity (Tib. gsal ba, Skt. svara) is a term which is also found in Indian Mahayana and refers to the cognitive power of the mind that allows phenomena to appear.[26][30] According to Sam van Schaik this aspect "seems to signify the immanent presence of the ground in all appearance, in that it is defined as all-encompassing and unobstructed."[23] Compassion is associated with the Nirmanakaya and the Sangha. According to Norbu, this compassionate energy manifests in three ways:[31][32]

- gDang (Skt. svaratā, radiance), this is an infinite and formless level of compassionate energy and reflective capacity, it is "an awareness free from any restrictions and as an energy free from any limits or form" (Norbu).[33]

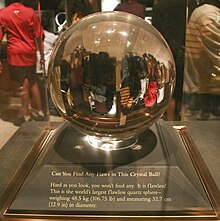

- rol pa (līlā, play), These are the manifestations which appear to be internal to the individual (such as when a crystal ball seems to reflect something inside itself).

- rTsal (vikrama, potentiality, dynamism) is "the manifestation of the energy of the individual him or herself, as an apparently 'external' world," though this apparent externality is only just "a manifestation of our own energy, at the level of Tsal" (Norbu).[34] This is explained through the use of a crystal prism which reflects and refracts white light into various other forms of light.

Namkhai Norbu warns that "all examples used to explain the nature of reality can only ever be partially successful in describing it because it is, in itself, beyond words and concepts."[35] Furthermore, he writes that "the Base should not be objectified and considered as a self-existing entity; it is the insubstantial State or condition which serves as the basis of all entities and individuals, of which the ordinary individual is unaware but which is fully manifest in the realized individual."[36]

The text, An Aspirational prayer for the Ground, Path and Result defines the three aspects of the basis thus:

Because its essence is empty, it is free from the limit of eternalism.

Because its nature is luminous, it is free from the extreme of nihilism.

Because its compassion is unobstructed, it is the ground of the manifold manifestations.[37]

See also

[edit]- Enlightenment in Buddhism – Goal of Buddhist practice

- Seventeen tantras – Collection of Dzogchen tantras

- Sky gazing – Tibetan Buddhist practice

- Trekchö – Dzogchen "cutting through" practice

- Tögal – Dzogchen visual meditation practice

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Longchenpa as quoted in Duckworth (2009), p. 104.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Nyoshul Khenpo (2016), ch. 6.

- ^ Rossi (1999), p. 52.

- ^ Dudjom Rinpoche (1991), p. 354.

- ^ a b c van Schaik (2004), p. 52.

- ^ a b c Smith (2016), pp. 12–13.

- ^ Hatchell (2014), p. 56.

- ^ Smith (2016), pp. 16–17.

- ^ Berzin (n.d.).

- ^ Pettit (1999), p. 79.

- ^ a b Smith (2016), p. 14.

- ^ Smith (2016), p. 17.

- ^ Pettit (1999), p. 78.

- ^ van Schaik (2004), p. 63-66.

- ^ Smith (2016), p. 12.

- ^ Smith (2016), p. 16.

- ^ Hatchell (2014), p. 57.

- ^ Norbu (2000), p. 89.

- ^ a b Achard (2015).

- ^ Norbu (2000), pp. 149–150.

- ^ Norbu (2000), p. 95-99.

- ^ a b Smith (2016), pp. 13, 30.

- ^ Pettit (1999), pp. 78–79.

- ^ a b c van Schaik (2004), p. 52-53.

- ^ Norbu (2000), p. 95-100.

- ^ a b Norbu (2000), p. 97.

- ^ a b c van Schaik (2004), p. 53.

- ^ Smith (2016), pp. 15, 224.

- ^ Hatchell (2014), p. 58.

- ^ Smith (2016), p. 13.

- ^ Smith (2016), p. 13, 222.

- ^ Norbu (2000), p. 99-101.

- ^ van Schaik (2004), p. 54.

- ^ Norbu (2000), p. 100.

- ^ Norbu (2000), p. 101.

- ^ Norbu (2000), p. 94.

- ^ Norbu (2000), p. 90.

- ^ Germano (1994).

Works cited

[edit]- Achard, Jean-Luc (2015). "The View of spyi-ti yoga". Revue d'Études Tibétaines. CNRS: 1–20. Retrieved 2021-09-05.

- Berzin, Alexander (n.d.). "The Major Facets of Dzogchen". StudyBuddhism.com. Retrieved 2021-09-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Duckworth, Douglas S. (2009). Mipam on Buddha-nature: The Ground of the Nyingma Tradition. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-7522-5. OCLC 320185179.

- Dudjom Rinpoche (1991). The Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism: its Fundamentals and History. Vol. Two Volumes. Translated by Gyurme Dorje with Matthew Kapstein. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-087-8.

- Germano, David F. (Winter 1994). "Architecture and Absence in the Secret Tantric History of rDzogs Chen". The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. 17 (2): 203–335. Retrieved 2021-09-05.

- Hatchell, Christopher (2014). Naked Seeing The Great Perfection, the Wheel of Time, and Visionary Buddhism in Renaissance Tibet. Oxford University Press.

- Norbu, Namkhai (2000). The Crystal and the Way of Light: Sutra, Tantra, and Dzogchen. Snow Lion Publications.

- Nyoshul Khenpo (2016). The Fearless Lion's Roar: Profound Instructions on Dzogchen, the Great Perfection. Shambhala Publications.

- Pettit, John Whitney (1999). Mipham's beacon of certainty: illuminating the view of Dzogchen, the Great Perfection. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-0-86171-157-4.

- Rossi, Donatella (1999). The Philosophical View of the Great Perfection in the Tibetan Bon Religion. Snow Lion. ISBN 1-55939-129-4.

- Smith, Malcolm (2016). Buddhahood in This Life: The Great Commentary by Vimalamitra. Simon and Schuster.

- van Schaik, Sam (2004). Approaching the Great Perfection: Simultaneous and Gradual Methods of Dzogchen Practice in the Longchen Nyingtig. Wisdom Publications.

Further reading

[edit]- Lipman, Kennard (1991) [1977]. "How Samsara is Fabricated from the Ground of Being" [Klong-chen rab-'byams-pa's "Yid-bzhin rin-po-che'i mdzod"]. Crystal Mirror V (rev. ed.). Berkeley: Dharma Publishing. pp. 336–356.

- Longchen, Rabjam (1998). The Precious Treasury of the Way of Abiding. Translated by Richard Barron. Junction City, CA: Padma Publishing.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch