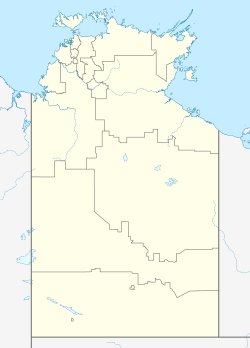

Gunbalanya, Northern Territory

| Gunbalanya Kunbarlanja (Gunwinggu) Northern Territory | |

|---|---|

A view of Gunbalanya from nearby Injalak Hill | |

| Coordinates | 12°19′S 133°03′E / 12.317°S 133.050°E |

| Population | 1,153 (UCL 2021)[1] |

| Location | 300 km (186 mi) east of Darwin |

| LGA(s) | West Arnhem Region |

| Region | Arnhem Land |

| Territory electorate(s) | Arafura |

| Federal division(s) | Lingiari |

Gunbalanya (also spelt Kunbarlanja, and historically referred to as Oenpelli) is an Aboriginal Australian town in west Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory of Australia, about 300 kilometres (190 mi) east of Darwin. The main language spoken in the community is Kunwinjku (a dialect of Bininj Kunwok). At the 2021 Australian census, Gunbalanya had a population of 1,177.[2]

Only accessible by air during the wet season, Gunbalanya is known for its Aboriginal art, in particular rock art and bark painting. It has a range of services, including a police station, school and community arts centre, Injalak Arts.

It is the nearest town to the Awunbarna, also known as Mount Borradaile, an Aboriginal sacred site and the location of significant Indigenous Australian rock art.

Etymology and history

[edit]The area now known as Gunbalanya was originally called "Uwunbarlany" by Erre-speaking people, who were its original inhabitants.[3] Oenpelli was the way Paddy Cahill (c. 1863–1923),[4] the founder of the original cattle station in the area, pronounced the local word.[5] The present toponym is an anglisation of the word Kunbarlanja[6] current in Kunwinjku, the language of the people who now live there, who began moving into the area from the east following the Cahill's establishment of his cattle station there in 1909.[citation needed]

Oenpelli, as it was known then, was established by the Rev. Alfred Dyer as a mission in 1925 by the Church of England's Church Missionary Society, on the former cattle station.[7] Dyer and his wife Mary established a typical mission station, with church, school, dispensary, garden, and store, to which they added pastoral work with feral cattle and horses.[citation needed] Among those who attended the mission school was the celebrated Gagudju elder and interpreter of culture, Bill Neidjie.[8]

The eldest son of the senior traditional owner of the land, Nipper Marakarra, Narlim, was born in 1909 and grew up at the mission. He continued to stay there as he wanted to have his children taught English, and also saw it as a way to stay on Country as traditional custodians. However, when a visiting policeman in the late 1930s found that Narlim had an infectious disease, he handcuffed him in order to chain him up with a group of others who were being sent to Darwin. Narlim was sent away under police escort, with his baby daughter on his shoulder. He never returned, but his daughter, Peggy did, and later became a community leader.[9]

In 1933, Nell Harris, a young woman of 29 years old, was taught Kunwinkju by the local people, and, along with Hannah Mangiru and Rachel Maralngurra, translated the Gospel of Mark into the language.[9]

Oenpelli remained a mission until 1975, when responsibility was transferred to an Aboriginal town council and the name was changed to Gunbalanya.[citation needed]

The 1948 American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land visited Oenpelli for three months and collected a large array of local artefacts, art, and specimens. Leader of the Expedition Charles Mountford returned to Oenpelli in 1949, when the Adelaide Advertiser reported his ‘new’ discovery of cave paintings at Obiri—a shelter 18m long and 2.7m high which contained tens of thousands of figures. Mountford proposed that the site be made a national reserve.[10]

Use of the name Oenpelli

[edit]The large and uncommon Oenpelli python, Morelia oenpelliensis, shares the historic name of this community,[11] as does Oenpelli bloodwood, Corymbia dunlopiana.[12]

A geological event known as the Oenpelli Dolerite intrusive event occurred about 1,720 million years ago.[13][14]

People and surrounds

[edit]The local people speak Kunwinjku (a dialect of Bininj Kunwok), and are a grouping of the Bininj peoples. At the 2016 Australian census, Gunbalanya had a population of 1,116.[15] 88.6% of the population identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander.[16]

Gunbalanya is the largest town in the area and the nearest population centre to Awunbarna, also known as Mount Borradaile, a mountain about 120 metres (390 ft) above sea level about 34.9 kilometres (21.7 mi) away.[17][18] Awunbarna is a sacred site and the location of a significant number of rock paintings.[19][20] A study published in 2020 recording the Maliwawa Figures describes paintings at 87 sites across western Arnhem Land from Awunbarna westwards to the Wellington Range.[21][22]

Access, facilities, and tourism

[edit]

The sealed Arnhem Highway links Darwin to Jabiru, the town within Kakadu National Park. About 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) before Jabiru, the sealed road turns off to Ubirr, the Border Store, Cahill's Crossing on the East Alligator River, and Oenpelli. The road is dirt from the East Alligator to just before Gunbalanya, a distance of about 16 kilometres (9.9 mi). While this road is generally navigable by four-wheel drive vehicle, the river crossing is a causeway which is closed by flooding during the wet season (November to April) and at high tides.[citation needed]

Dry season travellers are able to drive the 300 kilometres (190 mi) from Darwin in about three hours and 60 kilometres (37 mi) from Jabiru in under an hour. Northern Land Council permits are required to cross the East Alligator River, the western boundary of Arnhem Land, and travel east to Gunbalanya, obtainable from offices in Darwin or Jabiru. These may take up to two weeks to finalise, and many visitors prefer to see Arnhem Land through an organised tour operation.

Oenpelli Airport is a sealed all weather airstrip located in Gunbalanya, and a number of companies offer charter flights to and from this airport.

The town is regarded as one of the major Aboriginal towns in Arnhem Land, and includes a school (pre-school to Year 12), health clinic, service station, police station, aged care, recreational clubs, community arts centre (Injalak Arts), and various stores.

The Stone Country Festival (formerly Gunbalanya Cultural Open Day) is usually held in August and access for this is allowed without permit. Though an annual event, it is sometimes not able to be organised in a given year.

The local radio station is called "RIBS" for Remote Indigenous Broadcasting Service.[citation needed]

Indigenous art

[edit]

Rock art

[edit]Western Arnhem Land is home to some of the most significant rock art in the world.

Local artistic traditions are continued and adapted by the Injalak Arts Centre. Injalak Arts is named after nearby Injalak Hill, which has many rock art galleries and is the main tourist attraction in Gunbalanya.

Bark painting

[edit]In the 1960s the mission at Oenpelli encouraged traditional rock painting artists to paint on bark. These painted barks were sold to anthropologists and travellers. This soon became a cottage industry, and several important Aboriginal artists, including Lofty Bardayal, Mick Kubarrku[23] and Dick Murramurra[24] transferred their rock art skills to bark. These bark paintings are now held in art galleries in Australia and across the world. Exhibitions of bark paintings include "Old Masters"[25] at the National Museum of Australia and "Crossing Country"[26] at the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

In film

[edit]Parts of the 2020 film High Ground was filmed in the area, and the story reflects some of the history of the region, including a fictionalised version of the Gan Gan massacre.[9]

In the Anime film "Mobile Suit Gundam Hathaway", the town features as a rally point of an assembling group of "rebel" supporters, of the Group "Mafty", with over 30,000 supporters of the group having amassed at the time of the events in the film. The in world name of the town is spelled as "Oenbelli" due to a computing error during the towns registration in the space emigration era.

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Gunbalanya (Oenpelli) (1991–2013) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 37.8 (100.0) | 36.7 (98.1) | 36.7 (98.1) | 38.2 (100.8) | 36.3 (97.3) | 35.7 (96.3) | 36.0 (96.8) | 37.7 (99.9) | 39.4 (102.9) | 41.1 (106.0) | 41.6 (106.9) | 39.9 (103.8) | 41.6 (106.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 33.1 (91.6) | 32.7 (90.9) | 33.2 (91.8) | 33.7 (92.7) | 33.0 (91.4) | 31.9 (89.4) | 32.0 (89.6) | 33.5 (92.3) | 36.0 (96.8) | 37.4 (99.3) | 37.2 (99.0) | 35.0 (95.0) | 34.1 (93.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 24.8 (76.6) | 24.7 (76.5) | 24.7 (76.5) | 24.0 (75.2) | 21.9 (71.4) | 19.8 (67.6) | 18.6 (65.5) | 18.3 (64.9) | 20.1 (68.2) | 22.5 (72.5) | 24.1 (75.4) | 24.8 (76.6) | 22.4 (72.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 20.8 (69.4) | 21.0 (69.8) | 21.4 (70.5) | 17.2 (63.0) | 14.4 (57.9) | 10.4 (50.7) | 10.0 (50.0) | 9.8 (49.6) | 12.1 (53.8) | 14.4 (57.9) | 18.0 (64.4) | 20.7 (69.3) | 9.8 (49.6) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 384.9 (15.15) | 402.3 (15.84) | 268.1 (10.56) | 111.3 (4.38) | 10.6 (0.42) | 0.6 (0.02) | 0.1 (0.00) | 1.5 (0.06) | 4.3 (0.17) | 18.8 (0.74) | 108.0 (4.25) | 237.4 (9.35) | 1,537.4 (60.53) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 18.6 | 18.0 | 16.8 | 7.4 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 7.1 | 15.0 | 86.9 |

| Source: Australian Bureau of Meteorology[27] | |||||||||||||

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Gunbalanya (urban centre and locality)". Australian Census 2021.

- ^ "SBS Australian Census Explorer". Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ Birch 2011, p. 313, n.3.

- ^ Clinch 1979.

- ^ Mulvaney 2004, p. 37.

- ^ Garde, Murray. "Kunbarlanja". Bininj Kunwok online dictionary. Bininj Kunwok Regional Language Centre. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ Mulvaney 2004, p. 58.

- ^ Mackinolty 2002.

- ^ a b c Gumurdul, Julie Narndal; Rademaker, Laura; May, Sally K. (9 February 2021). "How historically accurate is the film High Ground? The violence it depicts is uncomfortably close to the truth". The Conversation. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ Chapman, Denise; Russell, Suzy (2011). "The Responsibilities of Leadership: The records of Charles P. Mountford". In Thomas, Martin; Neale, Margot (eds.). Exploring the Legacy of the 1948 Arnhem Land Expedition. Canberra: ANU E Press. p. 263. ISBN 9781921666452.

- ^ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("Oenpelli", p. 193).

- ^ Dean Nicolle. "Eucalypt Diversity Gallery". Currency Creek Arboretum. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ Ranford, Cath; Melville, Paul; Bentley, Craig (August 2008). "Wellington Range Project Northern Territory EL 5893 Relinquishment Report" (PDF). Report No.: WR08-02. Cameco Australia Pty Lt. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ "Definition card for: Oenpelli Dolerite". Australian Stratigraphic Units Database. Australian Government. Geoscience Australia. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

...licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence.

- ^ Gunbalanya 2016.

- ^ "2016 Census QuickStats: Gunbalanya". quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "Awunbarna (Mount Borradaile)". bonzle.com. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "Mt. Borradaile, Arnhem Land, Northern Territory, Australia". Cruise Centres. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ Grove, Margaret (2003). "Woman, man, land: an example from Arnhem Land, North Australia". Before Farming. 2003 (2): 1–15. doi:10.3828/bfarm.2003.2.6. ISSN 2056-3264.

- ^ Roberts, David Andrew; Parker, Adrian (2003), Ancient ochres: the Aboriginal rock paintings of Mount Borradaile, JB Books

- ^ S.C.Taçon, Paul; May, Sally K. (30 September 2020). "Introducing the Maliwawa Figures: a previously undescribed rock art style found in Western Arnhem Land". The Conversation. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ Nichele, Amelia (4 October 2020). "A missing part of the rock art gallery". Cosmos Magazine.

- ^ "Mick Kubarrku oenpelli Artist". Aboriginal Bark Paintings. 26 October 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ "Dick Murramurra". Aboriginal Bark Paintings. 28 September 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ "Old Masters: Australia's great bark artists". National Museum of Australia. Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ "crossing country". Art Gallery of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ "Climate statistics for Australian locations- OENPELLI". 8 July 2024.

References

[edit]- Birch, Bruce (2011). "The American Clever Man (Marrkijbu Burdan Merika)". In Thomas, Martin; Neale, Margo (eds.). Exploring the Legacy of the 1948 Arnhem Land Expedition. Australian National University. pp. 313–335. ISBN 978-1-921-66645-2.

- Clinch, M. A. (1979). "Cahill, Patrick (Paddy) (1863–1923)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 7. Melbourne University Press.

- Mackinolty, Chips (17 June 2002). "The man who attended his own wake:Big Bill Neidjie, Kakadu Man, circa WWI-2002". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- Mulvaney, Derek John (2004). Paddy Cahill of Oenpelli. Aboriginal Studies Press. ISBN 978-0-855-75456-3.

- "Gunbalanya". West Arnhem Regional Council. 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Birch, Bruce 'Erre Mengerrdji Urningangk: Three Languages From The Alligator Rivers Region of North Western Arnhem Land, Northern Territory, Australia', Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation, 2006

- Aboriginal Arts Board of the Australia Council, Oenpelli Bark Painting, Ure Smith, 1979

- Cole, Keith, A History of Oenpelli, Nungalinya Publications, 1975

- Cole, Keith, Arnhem Land: Places and People, Rigby, 1980

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch